Rick Just's Blog, page 182

October 27, 2019

First Women Legislators

In 1896, Idaho became the fourth state in the nation—preceded by Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah—to give women the right to vote. If you want to get technical, Idaho was actually the second state to do so, since Wyoming and Utah were both territories at the time. This was 23 years ahead of the 19th Amendment which gave that right to all women in the United States.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and the perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with divers men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband hand slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and the perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with divers men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband hand slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

Published on October 27, 2019 04:00

October 26, 2019

Miss Idaho Makes Good

Judy Lynn was a country star you didn’t hear much on the radio. Born Judy Lynn Voiten in Boise in 1936, she was just a teenager when she joined a touring company of the Grand Ole Opry. At 19, in 1955, she was crowned Miss Idaho.

Lynn put out 14 albums and 47 singles. Only four of the singles cracked the country charts, with s 1962’s “Footsteps of a Fool” doing the best, peaking at number seven.

But radio wasn’t Judy Lynn’s venue. Vegas was. She had her own show on The Strip for more than 20 years .

Judy Lynn Voiten, Miss Idaho, 1955.

Judy Lynn Voiten, Miss Idaho, 1955.

Lynn put out 14 albums and 47 singles. Only four of the singles cracked the country charts, with s 1962’s “Footsteps of a Fool” doing the best, peaking at number seven.

But radio wasn’t Judy Lynn’s venue. Vegas was. She had her own show on The Strip for more than 20 years .

Judy Lynn Voiten, Miss Idaho, 1955.

Judy Lynn Voiten, Miss Idaho, 1955.

Published on October 26, 2019 04:00

October 25, 2019

The Golden Elevator

When the center part of Idaho’s capitol building was built in 1905, the part with the dome, you could ride a special elevator to the fourth floor where the Idaho Supreme Court met. Over the years the wings were added to the building for the Idaho House and Senate. Sometime during a remodel the elevator was covered up. They found it again during renovation in 2007. It would lead to the JFAC hearing room today, if it was operable. It isn’t worth maintaining, but it is so pretty they decided to open it up for you to see it. It’s easy to miss, so if you’re wandering around looking at the beautiful building, be sure you ask where the old elevator is.

Published on October 25, 2019 04:00

October 24, 2019

Quarantined in Challis

The so-called Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 was the most severe pandemic in recent history, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An estimated 500 million people caught the flu worldwide. One in ten died from it, including about 675,000 in the United States.

There was no vaccine against the flu; no medical cure. One might avoid it by diligently practicing good hygiene, especially hand washing. The only sure way of staying free of the disease was quarantine. That’s the route many in Idaho took, quarantining themselves against it in their own homes. Some whole communities quarantined themselves. That caused a legal crisis in Challis.

The State Board of Health gave communities the right to self-quarantine, which Challis and some outlying areas chose to do. They posted guards on the roads leading into town to stop visitors from entering. There was flu in Salmon to the north and flu in Mackay to the south. The citizens of Challis were taking no chance with the deadly pandemic. You could enter the town if you quarantined yourself long enough to prove you didn’t have the flu.

But the lure of game was a call too strong for six hunters from Mackay to resist. On the night of November 5, 1918, they slipped past the road guard, and took a short cut up the Yankee Fork to Bonanza to reach their preferred hunting site on Loon Creek. What they shot, if anything, is lost to history. What is certain is that they were arrested and jailed in Clayton on their way back home.

The newly quarantined men got word to Mackay attorney Chase Clark—who would become Idaho’s 18th governor some two decades hence. He filed a writ of habeas corpus. District judge Frederick J. Gowen, sitting in Blackfoot, signed the order. Sheriff W.J. Huntington and county health board chair C.L. Curtley responded to the judge’s order with a “No.”

The judge charged the county officials with contempt of court and ordered them to show up in Arco on November 11 to face charges. Before that date, though, the incubation time had passed, proving the hunters did not have the flu. The sheriff released them.

Judge Cowen made a personal trip to Challis to meet with officials. Meet them he did, at a barricade outside of town. Several riled-up citizens challenged the judge to step across a line into the quarantined zone. He did so. The man was unharmed, but tensions were high. He did not linger long in Challis. Shortly after he left, he called the Attorney General in Boise requesting that troops be sent to Challis to maintain order.

This was all happening in the final days of World War I, so the question, “What troops?” was in order. With the contempt charges still pending, Governor Moses Alexander was getting pressure from both sides of the issue. Two competing Custer County Defense Councils, one from Mackay and one from Challis, were vying for the governor’s attention. One sent him a telegram of 777 words, so counted by some reporter probably because telegrams were priced by the word.

Governor Alexander sent his secretary, R.S. Madden to try to work out a compromise that would keep the county officials out of jail and let Challis retain its quarantine. After spending a day in Challis. Madden sent a telegram of five words to the governor, “Armistice declared. Be home Monday.”

Soon thereafter Challis modified its quarantine to allow people to enter the town with a yellow flag flying from their vehicle to identify them as possible carriers of the flu. It wasn’t long before Challis abandoned its quarantine altogether.

It turned out that wasn’t such a good idea. Dick d’Easum, writing about the incident in his 1959 book Fragments of Villainy gave a sad postscript to the story. He talked with retired Forest Service employee Al Moats who was in Challis at the time. Motts said, “What happened after the excitement was that Challis got the flu. Nobody knows where it came from, but it was bad. A lot of people died.”

There was no vaccine against the flu; no medical cure. One might avoid it by diligently practicing good hygiene, especially hand washing. The only sure way of staying free of the disease was quarantine. That’s the route many in Idaho took, quarantining themselves against it in their own homes. Some whole communities quarantined themselves. That caused a legal crisis in Challis.

The State Board of Health gave communities the right to self-quarantine, which Challis and some outlying areas chose to do. They posted guards on the roads leading into town to stop visitors from entering. There was flu in Salmon to the north and flu in Mackay to the south. The citizens of Challis were taking no chance with the deadly pandemic. You could enter the town if you quarantined yourself long enough to prove you didn’t have the flu.

But the lure of game was a call too strong for six hunters from Mackay to resist. On the night of November 5, 1918, they slipped past the road guard, and took a short cut up the Yankee Fork to Bonanza to reach their preferred hunting site on Loon Creek. What they shot, if anything, is lost to history. What is certain is that they were arrested and jailed in Clayton on their way back home.

The newly quarantined men got word to Mackay attorney Chase Clark—who would become Idaho’s 18th governor some two decades hence. He filed a writ of habeas corpus. District judge Frederick J. Gowen, sitting in Blackfoot, signed the order. Sheriff W.J. Huntington and county health board chair C.L. Curtley responded to the judge’s order with a “No.”

The judge charged the county officials with contempt of court and ordered them to show up in Arco on November 11 to face charges. Before that date, though, the incubation time had passed, proving the hunters did not have the flu. The sheriff released them.

Judge Cowen made a personal trip to Challis to meet with officials. Meet them he did, at a barricade outside of town. Several riled-up citizens challenged the judge to step across a line into the quarantined zone. He did so. The man was unharmed, but tensions were high. He did not linger long in Challis. Shortly after he left, he called the Attorney General in Boise requesting that troops be sent to Challis to maintain order.

This was all happening in the final days of World War I, so the question, “What troops?” was in order. With the contempt charges still pending, Governor Moses Alexander was getting pressure from both sides of the issue. Two competing Custer County Defense Councils, one from Mackay and one from Challis, were vying for the governor’s attention. One sent him a telegram of 777 words, so counted by some reporter probably because telegrams were priced by the word.

Governor Alexander sent his secretary, R.S. Madden to try to work out a compromise that would keep the county officials out of jail and let Challis retain its quarantine. After spending a day in Challis. Madden sent a telegram of five words to the governor, “Armistice declared. Be home Monday.”

Soon thereafter Challis modified its quarantine to allow people to enter the town with a yellow flag flying from their vehicle to identify them as possible carriers of the flu. It wasn’t long before Challis abandoned its quarantine altogether.

It turned out that wasn’t such a good idea. Dick d’Easum, writing about the incident in his 1959 book Fragments of Villainy gave a sad postscript to the story. He talked with retired Forest Service employee Al Moats who was in Challis at the time. Motts said, “What happened after the excitement was that Challis got the flu. Nobody knows where it came from, but it was bad. A lot of people died.”

Published on October 24, 2019 04:00

October 23, 2019

Bear Track Williams

Not all property owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) is a state park. One little known site is called “Bear Track” Williams Recreation Area. Though owned by IDPR, it is managed by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. That’s because the site is primarily for fishing access.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Published on October 23, 2019 04:00

October 22, 2019

THE State Flag

In doing research for my upcoming book, Symbols, Signs, and Songs, due out in November, I ran across a little interesting history on Idaho’s state flag. Since it is largely the state seal centered on a blue background, one would think we would have had an Idaho state flag for as long as we’ve had a seal since 1891. Not so.

It took the Legislature 17 years to pass a law creating an Idaho State Flag. Even then they punted to the adjutant general, delegating the duty of coming up with the design and specifying that the flag would be blue and have the word Idaho on it. They appropriated 100 dollars to make that happen on March 12, 1907.

It seemed odd to me that they put 100 dollars in the adjutant general’s budget. Why would he need anything? He could just send a flag company a picture of the state seal and tell them how it was supposed to appear on flags. Voila! Make some flags!

My misunderstanding was that the 100 dollars was for the cost of making a single flag. The state wasn’t planning on waving a flag from every courthouse in Idaho. The Legislature had the adjutant general design then order one flag.

Idaho got along with a single official state flag for years. It made the headlines in 1926 that the flag was traveling out of state with Governor C.C. Moore so that both could attend the governors’ conference in Cheyenne. The stay-at-home flag had only travelled out of state a couple of times before that. It lived in the governor’s office when not visiting other states. Today that original flag is in the possession of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Idaho's original state flag. Image from the physical photos file at the Idaho State Archives.

Idaho's original state flag. Image from the physical photos file at the Idaho State Archives.

It took the Legislature 17 years to pass a law creating an Idaho State Flag. Even then they punted to the adjutant general, delegating the duty of coming up with the design and specifying that the flag would be blue and have the word Idaho on it. They appropriated 100 dollars to make that happen on March 12, 1907.

It seemed odd to me that they put 100 dollars in the adjutant general’s budget. Why would he need anything? He could just send a flag company a picture of the state seal and tell them how it was supposed to appear on flags. Voila! Make some flags!

My misunderstanding was that the 100 dollars was for the cost of making a single flag. The state wasn’t planning on waving a flag from every courthouse in Idaho. The Legislature had the adjutant general design then order one flag.

Idaho got along with a single official state flag for years. It made the headlines in 1926 that the flag was traveling out of state with Governor C.C. Moore so that both could attend the governors’ conference in Cheyenne. The stay-at-home flag had only travelled out of state a couple of times before that. It lived in the governor’s office when not visiting other states. Today that original flag is in the possession of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Idaho's original state flag. Image from the physical photos file at the Idaho State Archives.

Idaho's original state flag. Image from the physical photos file at the Idaho State Archives.

Published on October 22, 2019 04:00

October 21, 2019

Our Dwindling Sockeye

That famous red fish, the sockeye has been a part of Idaho’s environment since long before man came to live here. The fish started making the newspapers early on in the state’s history. In 1899 the Idaho Statesman was reporting on the planting of sockeye eggs. Most references to sockeye salmon were in the grocery ads, starting at ten cents a can in the 1890s and rising to 59 cents for a “half-sized can” in 1956.

The Silver Blade newspaper in Rathdrum ran a report on fisheries on the Columbia August 19, 1899, that said, “The records for catching sockeye salmon were broken one day last week. At the Pacific-American Fisheries company’s cannery 136,000 were received. Of these 80,000 were sockeyes.”

That same year, the Cottonwood Report noted an estimated sockeye salmon pack of Puget Sound to 510,000 cases for the year.

The installation of dams on the Columbia and other manmade issues caused a dramatic drop in wild sockeye making their way back to Idaho. Fewer than 50 returned to Redfish Lake in 1958.

In 1991 the species was declared endangered. In 1992 a single fish, nicknamed Lonesome Larry, made it back to Redfish Lake.

The most recent ten-year average has been 690 returning to the Sawtooth Basin. In 2017 157 fish returned. This year only 53 had made it past the Lower Granite Dam at the time this post was scheduled.

Today, the Eagle Island Fish Hatchery raises sockeye salmon near Boise in an attempt to keep the fish from going extinct.

The Silver Blade newspaper in Rathdrum ran a report on fisheries on the Columbia August 19, 1899, that said, “The records for catching sockeye salmon were broken one day last week. At the Pacific-American Fisheries company’s cannery 136,000 were received. Of these 80,000 were sockeyes.”

That same year, the Cottonwood Report noted an estimated sockeye salmon pack of Puget Sound to 510,000 cases for the year.

The installation of dams on the Columbia and other manmade issues caused a dramatic drop in wild sockeye making their way back to Idaho. Fewer than 50 returned to Redfish Lake in 1958.

In 1991 the species was declared endangered. In 1992 a single fish, nicknamed Lonesome Larry, made it back to Redfish Lake.

The most recent ten-year average has been 690 returning to the Sawtooth Basin. In 2017 157 fish returned. This year only 53 had made it past the Lower Granite Dam at the time this post was scheduled.

Today, the Eagle Island Fish Hatchery raises sockeye salmon near Boise in an attempt to keep the fish from going extinct.

Published on October 21, 2019 04:00

October 20, 2019

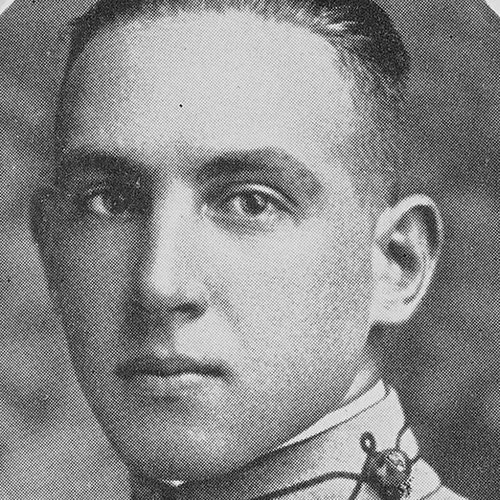

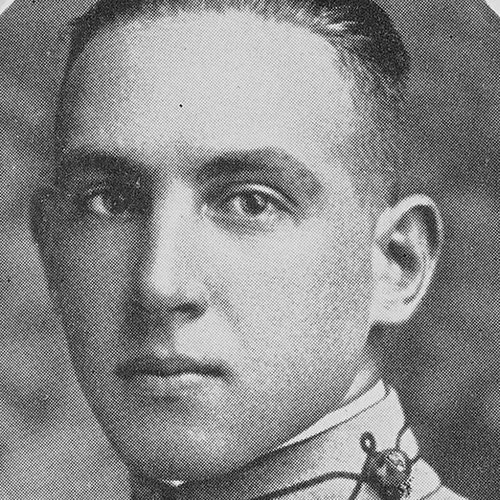

Stewart Hoover

Stewart W. Hoover was born on Independence Day, 1895 in Montpelier, Idaho. When he was 10 his father, Dr. Clayton A. Hoover was named Medical Superintendent of the Idaho State Insane Asylum, so the family moved to Blackfoot.

Stewart enjoyed his new life in Blackfoot, a place that allowed him to ride horses, hunt, take nature walks with his dog, and play basketball. He was well liked in school, where he studied hard and became his class valedictorian when he graduated from Blackfoot High in 1911.

Hoover applied for the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, was accepted, and began his studies there in 1913. At the Academy he was among many serious students and kept himself in the background for the most part. One exception was when he saved a child from drowning in nearby Lusk Reservoir. Stewart Hoover graduated in 1917 as a second lieutenant and was quickly promoted to first lieutenant.

By June 29, Hoover was in France. He was named a temporary captain of infantry on August 5, 1917.

In the spring of 1918, his family received a dreadful announcement, which began, “I have the honor to inform you that Captain Stewart W. Hoover of Company "I", Eighteenth Infantry, was killed in battle on March 1st. There is no officer in this regiment who has had a better record for gallantry than Captain Hoover and he was killed at the head of his company during a desperate encounter with German storm troops.”

Hoover met his end when a German shell exploded near where he was standing with a gun leveled at the enemy. He was the first soldier from Idaho to die in World War I, and the first West Point officer to die in that gruesome war.

Two American Legion posts are today named in his honor, one at West Point and the other in Blackfoot.

Stewart enjoyed his new life in Blackfoot, a place that allowed him to ride horses, hunt, take nature walks with his dog, and play basketball. He was well liked in school, where he studied hard and became his class valedictorian when he graduated from Blackfoot High in 1911.

Hoover applied for the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, was accepted, and began his studies there in 1913. At the Academy he was among many serious students and kept himself in the background for the most part. One exception was when he saved a child from drowning in nearby Lusk Reservoir. Stewart Hoover graduated in 1917 as a second lieutenant and was quickly promoted to first lieutenant.

By June 29, Hoover was in France. He was named a temporary captain of infantry on August 5, 1917.

In the spring of 1918, his family received a dreadful announcement, which began, “I have the honor to inform you that Captain Stewart W. Hoover of Company "I", Eighteenth Infantry, was killed in battle on March 1st. There is no officer in this regiment who has had a better record for gallantry than Captain Hoover and he was killed at the head of his company during a desperate encounter with German storm troops.”

Hoover met his end when a German shell exploded near where he was standing with a gun leveled at the enemy. He was the first soldier from Idaho to die in World War I, and the first West Point officer to die in that gruesome war.

Two American Legion posts are today named in his honor, one at West Point and the other in Blackfoot.

Published on October 20, 2019 04:00

October 19, 2019

A Decade of Overland Stages

Stagecoaches are an icon of Westerns. They were always getting robbed and occasionally attacked by Indians. Unlike six-gun duels in the street, which were largely an invention of dime novels, stagecoaches deserve their icon status.

The best known and most successful of the stagecoach companies was the Overland Stage. Stagecoaches brought passengers and supplies, but their most important cargo was mail. Ben Holladay, who ran the company, had the US Mail contract which brought him more than a million dollars a year for a time. He built a mansion in Washington, DC just so he could lobby Congress for contracts.

Running a stage line was profitable, but it was also expensive and complicated. Holladay had to set up stage stations every 10 to 15 miles along his routes. The one that ran through Idaho started in Kansas. The stations had vast stores of shelled corn for the horses and men to take care of the animals. The Overland Stage could boast the capability of moving along at 100 miles a day, by rolling day and night. There were frequent delays, like the ones that ended up in the movies.

Newspapers depended on the arrival of other newspapers from across the country to supplement their local editions. On August 2, 1864, the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman published a story under the standing head By Overland Stage. It explained the delay in getting news from the company by listing some of the issues coaches had run into in recent days. About 100 miles out of Denver Indians had stolen all the Overland Stage Livestock. A stage near Fort Bridger, Wyoming had also been stopped by Indians. A third stage was attacked near Platte Bridge.

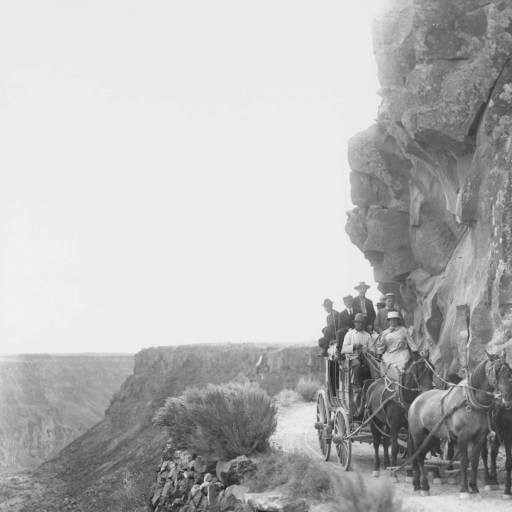

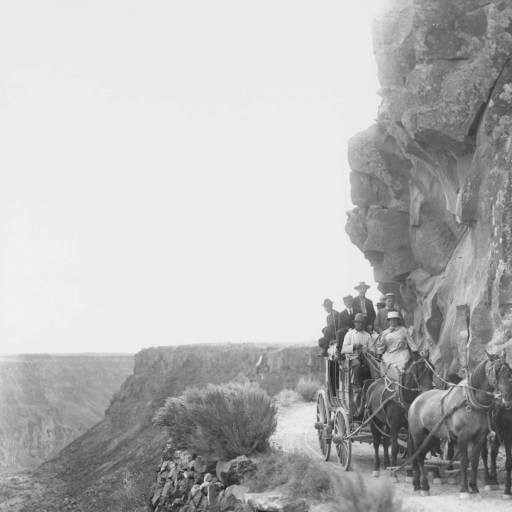

The coaches were comfortable when compared with walking. All the Overland Stages were built on a standard pattern called The Concord Coach. They had heavy leather springs and were pulled by four or six horses. Passengers piled in and piled on. The company was all about profit, so they didn’t necessarily go on a schedule. They would often wait until a stage was full of people and supplies. The picture shows a stagecoach (perhaps not an Overland) on a road along the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls. It is one of the Idaho State Historical Society’s photos from the Bisbee collection.

As important as they were, stagecoaches roamed the West for a fairly short time. The Overland Stage Company, which made Holladay a fortune, lasted about ten years. Holladay transitioned to railroads, which is the way the mail went. He lost most of his fortune trying to run trains.

The best known and most successful of the stagecoach companies was the Overland Stage. Stagecoaches brought passengers and supplies, but their most important cargo was mail. Ben Holladay, who ran the company, had the US Mail contract which brought him more than a million dollars a year for a time. He built a mansion in Washington, DC just so he could lobby Congress for contracts.

Running a stage line was profitable, but it was also expensive and complicated. Holladay had to set up stage stations every 10 to 15 miles along his routes. The one that ran through Idaho started in Kansas. The stations had vast stores of shelled corn for the horses and men to take care of the animals. The Overland Stage could boast the capability of moving along at 100 miles a day, by rolling day and night. There were frequent delays, like the ones that ended up in the movies.

Newspapers depended on the arrival of other newspapers from across the country to supplement their local editions. On August 2, 1864, the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman published a story under the standing head By Overland Stage. It explained the delay in getting news from the company by listing some of the issues coaches had run into in recent days. About 100 miles out of Denver Indians had stolen all the Overland Stage Livestock. A stage near Fort Bridger, Wyoming had also been stopped by Indians. A third stage was attacked near Platte Bridge.

The coaches were comfortable when compared with walking. All the Overland Stages were built on a standard pattern called The Concord Coach. They had heavy leather springs and were pulled by four or six horses. Passengers piled in and piled on. The company was all about profit, so they didn’t necessarily go on a schedule. They would often wait until a stage was full of people and supplies. The picture shows a stagecoach (perhaps not an Overland) on a road along the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls. It is one of the Idaho State Historical Society’s photos from the Bisbee collection.

As important as they were, stagecoaches roamed the West for a fairly short time. The Overland Stage Company, which made Holladay a fortune, lasted about ten years. Holladay transitioned to railroads, which is the way the mail went. He lost most of his fortune trying to run trains.

Published on October 19, 2019 04:00

October 18, 2019

The Idaho Scimitar

I’ve written before about Fred T. Dubois, fiery U.S. Senator from Idaho 1891-1897, and 1901-1907. He was a zealot about polygamy when he was U.S. Marshall for Idaho from 1882 to 1884, and continued his opposition in his national office. His anti-Mormonism was one reason Idaho Democrats lost the Legislature in 1907, which was why Dubois lost his seat. The newly elected Republican majority Legislature booted Dubois (this was when legislatures named U.S. Senators) and elected William Borah to replace him.

One little-remembered attempt to gin up more anti-Mormon sentiment was a newspaper he started in Boise, called The Idaho Scimitar. It published weekly on Saturdays, beginning with the November 2nd issue in 1907. Its aim was “the moral uplift of the people everywhere.” Advertisers were few. Most notably, in addition to anti-Mormon screeds, the paper published numerous notices about public lands opened up for settlement.

In the final issue of The Idaho Scimitar, on October 3, 1918, Dubois lamented the paper’s end, giving one more stab to the Mormons: “This immediate section of the great Rocky Mountain country, Utah, Wyoming and Idaho, is controlled by the Mormon organization politically. To my mind this polygamous and law-defying order is the greatest menace to our immediate civilization.”

His vitriol was not reserved solely for Mormons. He had little use for Indians, particularly Bannocks. In an 1895 article in the New York Times, he was quoted as saying, “The extermination of the whole lazy, shiftless, non-supporting tribe of Bannocks would not be any great loss.” His national office also gave him the opportunity to pass judgment on Filipinos, Hawaiians and “the American negro” in the Congressional Record, decrying their alleged lack of a work ethic.

Dubois lived his final years in Washington, DC, dying there on February 14, 1930. He is buried in the Grove City Cemetery in Blackfoot.

One little-remembered attempt to gin up more anti-Mormon sentiment was a newspaper he started in Boise, called The Idaho Scimitar. It published weekly on Saturdays, beginning with the November 2nd issue in 1907. Its aim was “the moral uplift of the people everywhere.” Advertisers were few. Most notably, in addition to anti-Mormon screeds, the paper published numerous notices about public lands opened up for settlement.

In the final issue of The Idaho Scimitar, on October 3, 1918, Dubois lamented the paper’s end, giving one more stab to the Mormons: “This immediate section of the great Rocky Mountain country, Utah, Wyoming and Idaho, is controlled by the Mormon organization politically. To my mind this polygamous and law-defying order is the greatest menace to our immediate civilization.”

His vitriol was not reserved solely for Mormons. He had little use for Indians, particularly Bannocks. In an 1895 article in the New York Times, he was quoted as saying, “The extermination of the whole lazy, shiftless, non-supporting tribe of Bannocks would not be any great loss.” His national office also gave him the opportunity to pass judgment on Filipinos, Hawaiians and “the American negro” in the Congressional Record, decrying their alleged lack of a work ethic.

Dubois lived his final years in Washington, DC, dying there on February 14, 1930. He is buried in the Grove City Cemetery in Blackfoot.

Published on October 18, 2019 04:00