Rick Just's Blog, page 180

November 16, 2019

Plastic Potatoes

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Brown plastic potato pins are ubiquitous in Idaho. Don't you have one? The Idaho Potato Commission will sell you a bag of 50 for $7. It was that commission, specifically its director Jay Sherlock, that came up with the idea for the pins.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

Published on November 16, 2019 04:00

November 15, 2019

Love (and Dog Food) For All

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

So, you were probably wondering what else the Idaho State Checkers Champion of 1938 was good at. Yes? It’s surprising to me this hasn’t already been covered extensively in all the papers, but it has not. If falls to me, then, to supply that missing knowledge.

As everyone knows, the 1938 Idaho State Checkers Champion was Alfred Wilke who lived just outside of Boise about two miles west of the Cole School. That’s right, the Cole School that is no longer there.

It’s hard to pin down what Wilke was best known for, outside of his wicked checkers skill. Many would remember him as the man who bred white leghorn chickens at his home, which he called Wilketon Hatchery. In 1930 you could buy 1,000 “chix” for $95. Some would recall that his wife had a little bird business on the side, selling singing canaries, “the finest in a decade” if you believed her classified ads.

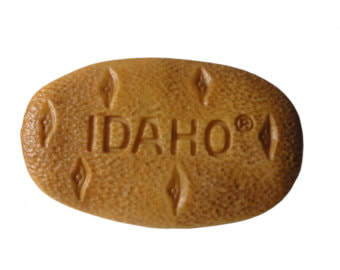

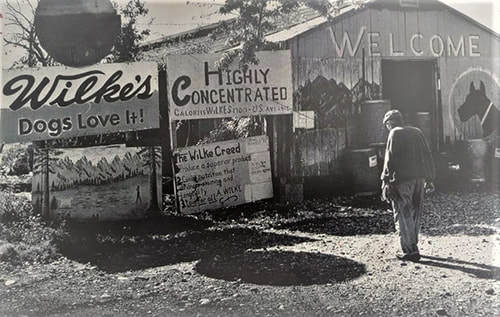

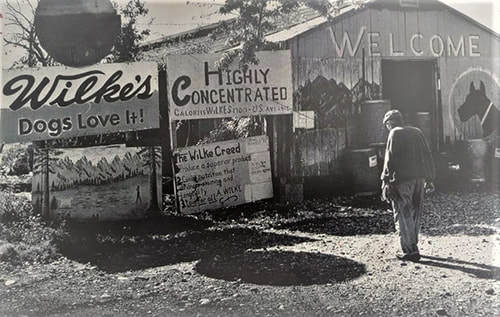

Working in all those chicken coops gave Wilke chronic bronchitis, so he switched careers in 1924. Taking what he’d learned about nutrition in the chicken business, he started Wilke’s Dog Food Plant at 8201 Fairview Avenue, where Boise Funeral Home is today. The establishment didn’t look like much, but the product was popular. Wilke sold the dog food all over Idaho and in adjoining states.

You can see in the photo that Wilke had a creed. The first point of the creed was to “Produce a superior product.” The second point can’t be read from the photo, but we know it involved nutrition and longevity. His third creed point was, “Love for all.” It almost sounds like he was building Subarus.

Wilke did love dogs. He bred and sold Irish setters and Airedales, “unprecedented guardians of the home,” in 1938.

One item in the picture to take special notice of is the landscape scene beneath the Wilke’s sign. Alfred Wilke was an amateur artist who participated in shows put on by the Boise Art Association and even had a show of his own in 1973 at Boise Blueprint, where they touted his “four decades of experience” in producing scenic Idaho art. No mention was made of his dog food or skill at checkers.

Alfred Wilke in front of his Fairview Avenue dog food manufacturing operation. Photo courtesy of Hugh Hartman.

Alfred Wilke in front of his Fairview Avenue dog food manufacturing operation. Photo courtesy of Hugh Hartman.

So, you were probably wondering what else the Idaho State Checkers Champion of 1938 was good at. Yes? It’s surprising to me this hasn’t already been covered extensively in all the papers, but it has not. If falls to me, then, to supply that missing knowledge.

As everyone knows, the 1938 Idaho State Checkers Champion was Alfred Wilke who lived just outside of Boise about two miles west of the Cole School. That’s right, the Cole School that is no longer there.

It’s hard to pin down what Wilke was best known for, outside of his wicked checkers skill. Many would remember him as the man who bred white leghorn chickens at his home, which he called Wilketon Hatchery. In 1930 you could buy 1,000 “chix” for $95. Some would recall that his wife had a little bird business on the side, selling singing canaries, “the finest in a decade” if you believed her classified ads.

Working in all those chicken coops gave Wilke chronic bronchitis, so he switched careers in 1924. Taking what he’d learned about nutrition in the chicken business, he started Wilke’s Dog Food Plant at 8201 Fairview Avenue, where Boise Funeral Home is today. The establishment didn’t look like much, but the product was popular. Wilke sold the dog food all over Idaho and in adjoining states.

You can see in the photo that Wilke had a creed. The first point of the creed was to “Produce a superior product.” The second point can’t be read from the photo, but we know it involved nutrition and longevity. His third creed point was, “Love for all.” It almost sounds like he was building Subarus.

Wilke did love dogs. He bred and sold Irish setters and Airedales, “unprecedented guardians of the home,” in 1938.

One item in the picture to take special notice of is the landscape scene beneath the Wilke’s sign. Alfred Wilke was an amateur artist who participated in shows put on by the Boise Art Association and even had a show of his own in 1973 at Boise Blueprint, where they touted his “four decades of experience” in producing scenic Idaho art. No mention was made of his dog food or skill at checkers.

Alfred Wilke in front of his Fairview Avenue dog food manufacturing operation. Photo courtesy of Hugh Hartman.

Alfred Wilke in front of his Fairview Avenue dog food manufacturing operation. Photo courtesy of Hugh Hartman.

Published on November 15, 2019 04:00

November 14, 2019

An Almost Army Base

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Idaho contributed to the war effort during World War II as the site of Farragut Naval Training Station, where more than 292,000 “boots” got their training. There was another training base proposed for Idaho about the same time. The Army even started construction on the site.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, and it is from his website where I obtained the information for this short piece. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

I urge you to read more about this on Tom’s site, and see the pictures of remaining foundations and other (pardon the pun) concrete evidence of the ill-fated base that can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Idaho contributed to the war effort during World War II as the site of Farragut Naval Training Station, where more than 292,000 “boots” got their training. There was another training base proposed for Idaho about the same time. The Army even started construction on the site.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, and it is from his website where I obtained the information for this short piece. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

I urge you to read more about this on Tom’s site, and see the pictures of remaining foundations and other (pardon the pun) concrete evidence of the ill-fated base that can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Published on November 14, 2019 04:00

November 13, 2019

The Importance of Links

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

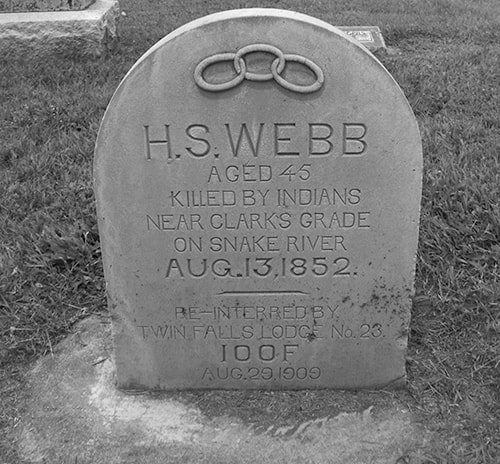

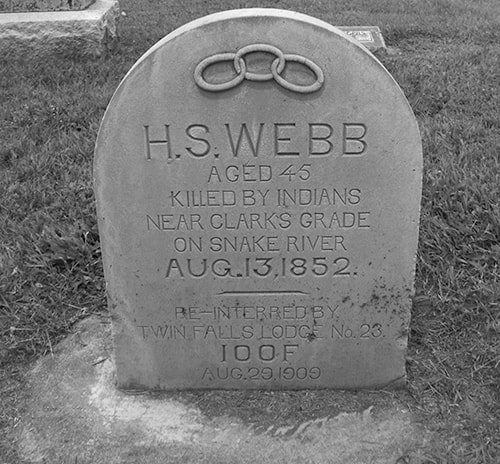

In June of 1908 someone found a gravesite associated with the Oregon Trail about seven miles from Twin Falls near the top of Clark’s Grade. Four graves were identified along with deteriorating wagon parts scattered in the area.

This seemed to tell the story of a massacre, probably by Indians, during which an immigrating family was killed, and their wagon destroyed. But there was more to the story. One of the gravesites was marked, pinning down the date of the massacre and giving the name of one of the victims.

The poplar marker had likely been cut from the family’s wagon. Because it faced east, and leaned slightly in that direction, the elements had not done its worst to the marker. It read, “H.S. Webb, August 13, ’52.” No markers were in evidence near the other graves. Speculation was that someone who knew Mr. Webb came along shortly after the massacre and buried he and his family.

But there was something else on the marker that piqued the interest of some in Twin Falls. Someone had carved three arching chain links into the wood. That symbol, connoting the motto, one word per link, of Friendship, Love, and Truth, is the symbol of the Odd Fellows. One of the tenants of the Odd Fellows fraternal organization is an ethic of reciprocity. Think Golden Rule. Some of the Twin Falls Odd Fellows apparently determined that what they would like for themselves if killed and buried where they fell, would be to have someone move their body to a dignified cemetery where a proper stone marker could be placed. In any case, that’s what they did, disinterring Mr. Webb and moving him to the Twin Falls Cemetery.

Upon digging up the fallen immigrant they discovered he had been buried in a three-foot hole. The upper half of his body was covered with barrel staves before dirt was added. Lava rocks had been placed over the grave to prevent it from being disturbed by wild animals.

From the bones the Odd Fellows determined that Webb was a large and powerfully built man about six feet tall and near 45 years of age when he was killed. From his jaw alone someone determined that he was probably “a determined and aggressive man.”

On August 29, 1909, just five years after the city was formed, the Odd Fellows and Rebekahs of Twin Fall Lodge 23 held a service in their hall, as well as a graveside service for H.S. Webb. One could only speculate whether or not the pioneer would have been pleased with his brothers for moving him away from the spot where his family is still buried.

Twin Falls Odd Fellows at the site of H.S. Webb's original grave in 1909. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Twin Falls Odd Fellows at the site of H.S. Webb's original grave in 1909. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

In June of 1908 someone found a gravesite associated with the Oregon Trail about seven miles from Twin Falls near the top of Clark’s Grade. Four graves were identified along with deteriorating wagon parts scattered in the area.

This seemed to tell the story of a massacre, probably by Indians, during which an immigrating family was killed, and their wagon destroyed. But there was more to the story. One of the gravesites was marked, pinning down the date of the massacre and giving the name of one of the victims.

The poplar marker had likely been cut from the family’s wagon. Because it faced east, and leaned slightly in that direction, the elements had not done its worst to the marker. It read, “H.S. Webb, August 13, ’52.” No markers were in evidence near the other graves. Speculation was that someone who knew Mr. Webb came along shortly after the massacre and buried he and his family.

But there was something else on the marker that piqued the interest of some in Twin Falls. Someone had carved three arching chain links into the wood. That symbol, connoting the motto, one word per link, of Friendship, Love, and Truth, is the symbol of the Odd Fellows. One of the tenants of the Odd Fellows fraternal organization is an ethic of reciprocity. Think Golden Rule. Some of the Twin Falls Odd Fellows apparently determined that what they would like for themselves if killed and buried where they fell, would be to have someone move their body to a dignified cemetery where a proper stone marker could be placed. In any case, that’s what they did, disinterring Mr. Webb and moving him to the Twin Falls Cemetery.

Upon digging up the fallen immigrant they discovered he had been buried in a three-foot hole. The upper half of his body was covered with barrel staves before dirt was added. Lava rocks had been placed over the grave to prevent it from being disturbed by wild animals.

From the bones the Odd Fellows determined that Webb was a large and powerfully built man about six feet tall and near 45 years of age when he was killed. From his jaw alone someone determined that he was probably “a determined and aggressive man.”

On August 29, 1909, just five years after the city was formed, the Odd Fellows and Rebekahs of Twin Fall Lodge 23 held a service in their hall, as well as a graveside service for H.S. Webb. One could only speculate whether or not the pioneer would have been pleased with his brothers for moving him away from the spot where his family is still buried.

Twin Falls Odd Fellows at the site of H.S. Webb's original grave in 1909. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Twin Falls Odd Fellows at the site of H.S. Webb's original grave in 1909. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Published on November 13, 2019 04:00

November 12, 2019

Hayden, Hayden, Hayden, and... Not Hayden

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

A reader asked where the name Hayden came from for Hayden Creek in North Idaho. It seemed like a simple request, and I found the answer quickly in Lalia Boone’s definitive Idaho Place Names. Probably. Her explanation for the name Hayden Creek referred to a creek in Lemhi County, not the one that flows into Hayden Lake. That Hayden Creek flows from Hayden Basin. The basin and creek were named for Jim Hayden who was an early packer and freighter in the area.

Hayden’s claim to fame was peppered with gunfire. Bill Smith, who was one of the first to discover gold in Leesburg, was playing cards with Jim Hayden in 1871. There was a dispute about a hand. Smith took umbrage at Hayden and fired at the man. Hayden was said to be unarmed, but he found a gun somewhere and shot back, killing Smith. Hayden was acquitted when he went to trial. His relief at that was short-lived. Hayden was killed by Indians in Birch Creek Valley in 1877.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boone's book. The lake and town are named after Matt Heyden (sic), so it follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Heyden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Heyden won. Why the name is spelled differently is not explained in Boone’s book, but the U.S. Postal Service was frequently the culprit, having a reputation at that time for little attention to detail.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

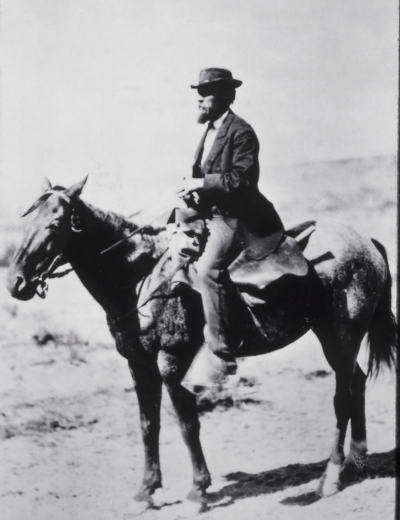

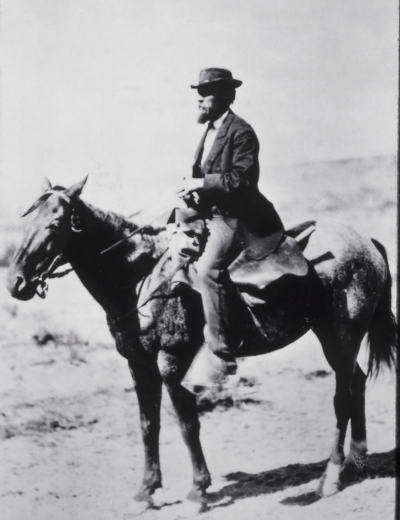

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

A reader asked where the name Hayden came from for Hayden Creek in North Idaho. It seemed like a simple request, and I found the answer quickly in Lalia Boone’s definitive Idaho Place Names. Probably. Her explanation for the name Hayden Creek referred to a creek in Lemhi County, not the one that flows into Hayden Lake. That Hayden Creek flows from Hayden Basin. The basin and creek were named for Jim Hayden who was an early packer and freighter in the area.

Hayden’s claim to fame was peppered with gunfire. Bill Smith, who was one of the first to discover gold in Leesburg, was playing cards with Jim Hayden in 1871. There was a dispute about a hand. Smith took umbrage at Hayden and fired at the man. Hayden was said to be unarmed, but he found a gun somewhere and shot back, killing Smith. Hayden was acquitted when he went to trial. His relief at that was short-lived. Hayden was killed by Indians in Birch Creek Valley in 1877.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boone's book. The lake and town are named after Matt Heyden (sic), so it follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Heyden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Heyden won. Why the name is spelled differently is not explained in Boone’s book, but the U.S. Postal Service was frequently the culprit, having a reputation at that time for little attention to detail.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

Published on November 12, 2019 04:00

November 11, 2019

A Horrendous Horse Tale

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Fame and infamy today, all wrapped up in one name.

The first steamboat to reach Lewiston was the sternwheeler Colonel Wright in 1859, captained by Leonard White. As the first of what would be countless vessels to ply the Columbia and Snake Rivers to that inland port, the Colonel Wright deserves its fame.

The infamy comes in when one explores the provenance of the boat’s name. It was named after Colonel George Wright who was known as an Indian fighter in Washington and Oregon territories at the time the steamer was built. He is probably best-known today as the military officer who ordered the horse slaughter.

A monument at mile marker 2 on the Washington side of the Centennial Trail that runs from Spokane to Coeur d’Alene tells the story of Horse Slaughter Camp. It’s within walking distance of the Idaho border, though in 1858 there was no border and no Idaho. The northern part of today’s Gem State was part of Washington Territory.

The monument tells the story: “In 1858 Col. George Wright with 700 soldiers was sent from Walla Walla to suppress an Indian outbreak. After defeating the Indians in two battles he captured 800 Indian horses. To prevent the Indians from waging further warfare he killed the horses on the bank of the river directly north of this monument.”

The date of the slaughter was September 8, 1858. The animals belonged to the Palouse Tribe.

Col. Wright kept back 150 horses for use by his soldiers. They proved intractable and were later destroyed.

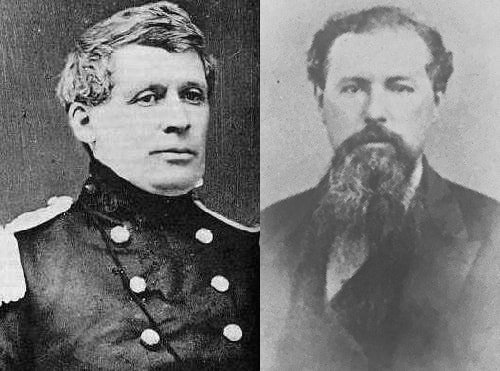

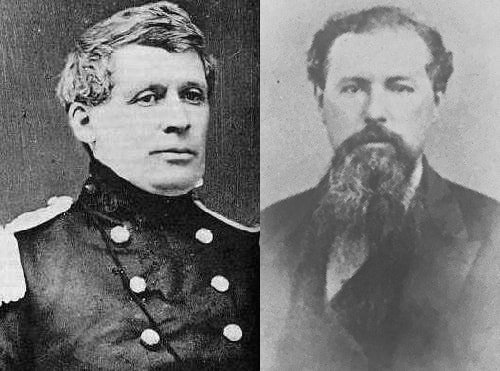

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

The first steamboat to reach Lewiston was the sternwheeler Colonel Wright in 1859, captained by Leonard White. As the first of what would be countless vessels to ply the Columbia and Snake Rivers to that inland port, the Colonel Wright deserves its fame.

The infamy comes in when one explores the provenance of the boat’s name. It was named after Colonel George Wright who was known as an Indian fighter in Washington and Oregon territories at the time the steamer was built. He is probably best-known today as the military officer who ordered the horse slaughter.

A monument at mile marker 2 on the Washington side of the Centennial Trail that runs from Spokane to Coeur d’Alene tells the story of Horse Slaughter Camp. It’s within walking distance of the Idaho border, though in 1858 there was no border and no Idaho. The northern part of today’s Gem State was part of Washington Territory.

The monument tells the story: “In 1858 Col. George Wright with 700 soldiers was sent from Walla Walla to suppress an Indian outbreak. After defeating the Indians in two battles he captured 800 Indian horses. To prevent the Indians from waging further warfare he killed the horses on the bank of the river directly north of this monument.”

The date of the slaughter was September 8, 1858. The animals belonged to the Palouse Tribe.

Col. Wright kept back 150 horses for use by his soldiers. They proved intractable and were later destroyed.

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Colonel George Wright, on the left, ordered the slaughter of some 800 Indian horses. Thomas Stump, on the right, was first captain of the Colonel Wright sternwheeler. Wright photo from the US Military Academy Archives. Stump photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Published on November 11, 2019 04:00

November 10, 2019

The Hanson Bridge

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

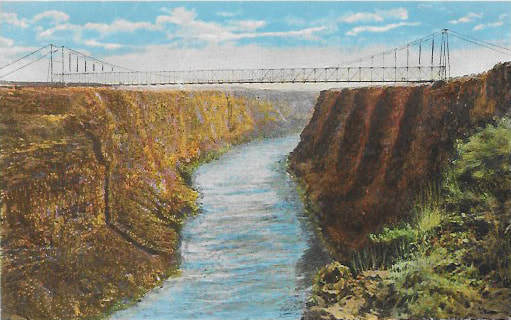

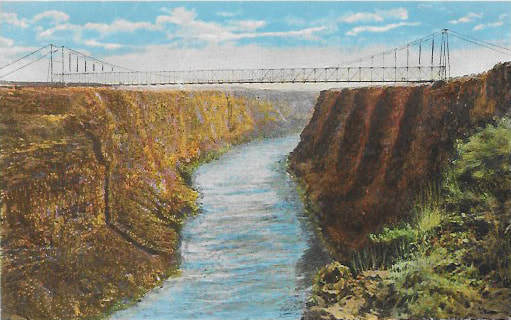

The Hansen Bridge, which spanned the Snake River Canyon near the town of Hansen, was a bit of a wonder in 1919 when it was built. It was 608 feet across, making it the second longest span in the country at the time. At 325 feet above the river, some accounts had it listed as being the highest suspension bridge in the world. And some accounts also listed it as being 345 feet above the Snake and 688 feet long. Break out your tape measure.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

The Hansen Bridge, which spanned the Snake River Canyon near the town of Hansen, was a bit of a wonder in 1919 when it was built. It was 608 feet across, making it the second longest span in the country at the time. At 325 feet above the river, some accounts had it listed as being the highest suspension bridge in the world. And some accounts also listed it as being 345 feet above the Snake and 688 feet long. Break out your tape measure.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Published on November 10, 2019 04:00

November 9, 2019

The Beauty of the Ugly Duckling

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

This is a picture of a beautiful woman. True, it’s a poor picture and not one on which beauty can be readily established. But if you were to ask any one of the hundreds of men and women she fed over the years you would likely get agreement on her beauty of a certain kind.

Miss Pearl Tyre ran a boarding house at 1023 Washington Street in Boise’s North End from 1934 to at least 1951. She also ran an open kitchen where people in need could eat for low or no cost, if they were willing to exchange chopping a little wood or sweeping floors for a meal.

This classified ad from the June 25, 1949 edition of the Idaho Statesman was typical: “You may fill your plate with delicious home cooked food at the kitchen stove of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria. Wash your own dishes one at a time under the hot water faucet.”

The Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria? Yes. One can only guess how Tyre came up with the name, but a good supposition is that it may have come from one way she acquired her food. Each day the local Safeway store would clean out their display racks, tossing the slightly wilted, tragically malformed, and bruised fruits and vegetables. Tyre made regular trips to the alley behind the grocery to salvage discarded, yet edible food. She would take it home, clean it up, and toss the vegetables into a stew pot.

Miss Tyre—she never married—was not judgmental, though she had once worked with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which at times came off as a bit judgy. As evidence of that we produce this ad from 1949, which may give us another clue about the establishment’s name: “The Ugly Duckling was hatched from a swan’s egg in a nest of common barnyard ducks. He was thought ugly by his companions, but became the most beautiful bird of them all. Do not be afraid of the Ugly Duckling period in your life, for it may lead to a superfine swan’s status. Meals for working for them or cash, $2.50 a week. Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria, 1023 Washington St., phone 832.”

The proprietress was active in several women’s organizations and was a founding member of the YWCA in Boise. At one time she worked as the librarian at the Idaho State Law Library. But it is her Kicheteria for which she was best remembered by the men and women to whom she offered a dignified meal and place to stay. And it wasn’t just down and outers she welcomed. Miss Tyre invited students from Boise High School to eat a good lunch for a little money, as well.

The community stepped up to help when called upon, as this thank you ad for Thanksgiving indicates: “We are grateful for the food that poured in, in answer to our request at Thanksgiving. Never in the 15 years of the kitcheteria have we seen men and women so hungry, ravenously hungry, eating 3 big meals a day. We are endeavoring to give them peace of mind and nourished bodies, so that they will leave us with a better outlook than when they came.”

But there’s still that odd name, not the Ugly Duckling part, but the “Kitcheteria.” Did Miss Tyre invent that word? Perhaps, but we should note that it was trademarked by the Harrington Hotel Co., Inc in 1956. Their Kitcheteria was a Washington, D.C. self-service dining establishment begun following World War II. It served more than a million meals from 1948-1991. That’s probably more than Miss Tyre served in her 17-year run in Boise, but they could not have been served with more respect than the diners got from the lady of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria.

Pearl Tyre, proprietress of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria.

Pearl Tyre, proprietress of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria.

This is a picture of a beautiful woman. True, it’s a poor picture and not one on which beauty can be readily established. But if you were to ask any one of the hundreds of men and women she fed over the years you would likely get agreement on her beauty of a certain kind.

Miss Pearl Tyre ran a boarding house at 1023 Washington Street in Boise’s North End from 1934 to at least 1951. She also ran an open kitchen where people in need could eat for low or no cost, if they were willing to exchange chopping a little wood or sweeping floors for a meal.

This classified ad from the June 25, 1949 edition of the Idaho Statesman was typical: “You may fill your plate with delicious home cooked food at the kitchen stove of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria. Wash your own dishes one at a time under the hot water faucet.”

The Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria? Yes. One can only guess how Tyre came up with the name, but a good supposition is that it may have come from one way she acquired her food. Each day the local Safeway store would clean out their display racks, tossing the slightly wilted, tragically malformed, and bruised fruits and vegetables. Tyre made regular trips to the alley behind the grocery to salvage discarded, yet edible food. She would take it home, clean it up, and toss the vegetables into a stew pot.

Miss Tyre—she never married—was not judgmental, though she had once worked with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which at times came off as a bit judgy. As evidence of that we produce this ad from 1949, which may give us another clue about the establishment’s name: “The Ugly Duckling was hatched from a swan’s egg in a nest of common barnyard ducks. He was thought ugly by his companions, but became the most beautiful bird of them all. Do not be afraid of the Ugly Duckling period in your life, for it may lead to a superfine swan’s status. Meals for working for them or cash, $2.50 a week. Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria, 1023 Washington St., phone 832.”

The proprietress was active in several women’s organizations and was a founding member of the YWCA in Boise. At one time she worked as the librarian at the Idaho State Law Library. But it is her Kicheteria for which she was best remembered by the men and women to whom she offered a dignified meal and place to stay. And it wasn’t just down and outers she welcomed. Miss Tyre invited students from Boise High School to eat a good lunch for a little money, as well.

The community stepped up to help when called upon, as this thank you ad for Thanksgiving indicates: “We are grateful for the food that poured in, in answer to our request at Thanksgiving. Never in the 15 years of the kitcheteria have we seen men and women so hungry, ravenously hungry, eating 3 big meals a day. We are endeavoring to give them peace of mind and nourished bodies, so that they will leave us with a better outlook than when they came.”

But there’s still that odd name, not the Ugly Duckling part, but the “Kitcheteria.” Did Miss Tyre invent that word? Perhaps, but we should note that it was trademarked by the Harrington Hotel Co., Inc in 1956. Their Kitcheteria was a Washington, D.C. self-service dining establishment begun following World War II. It served more than a million meals from 1948-1991. That’s probably more than Miss Tyre served in her 17-year run in Boise, but they could not have been served with more respect than the diners got from the lady of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria.

Pearl Tyre, proprietress of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria.

Pearl Tyre, proprietress of the Ugly Duckling Kitcheteria.

Published on November 09, 2019 04:00

November 8, 2019

A Persistent Rumor

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

One step over from history is persistent, salacious rumor. Such is the story of Frieda Bethmann, one-time resident of Pardee, Idaho.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.” The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

One step over from history is persistent, salacious rumor. Such is the story of Frieda Bethmann, one-time resident of Pardee, Idaho.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

Published on November 08, 2019 04:00

November 7, 2019

Beyond Panning

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

When you think of a miner, you probably picture some old Gabby Hayes character with a pinned back hat brim crouched over a stream with a pan, dreams of gold glittering in his eye. That’s not a bad picture of a prospector, because most miners (some of whom were also minors) started out that way. Panning for gold is slow and tedious. Shake, shake, shake, rinse, shake, shake, shake, rinse, and repeat until your beard grows down to your waist. Gold flecks are heavier than most of the surrounding material so they sink to the bottom of the pan. A good panner could sift through about a yard of sand and gravel a day. If they turned up $3 or $4 worth of gold, that was excellent. It was about what they might make for a day as, say, a captain in the army in the 1860s, or your average bricklayer in the East.

But miners did not dream of bricklayer wages. They wanted more. That’s why prospectors were typically testing the waters, so to speak, in search of a vein higher upstream. Let’s assume for a moment that they couldn’t find that ledge of quartz, but the quantity of gold in the stream gravel was pretty good. They were stuck with mining the streambed itself or an alluvial fan where water once ran. That’s called “placer mining.” In that case they needed a way to sift more sand and gravel faster in order to have more gold at the end of the day.

Rockers were boxes into which the miner dumped gravel and sand scooped from a stream bottom or alluvial deposit. At the top of the box was a sieve where the larger bits of gravel were screened out. Below that was an incline set up with a series of bumps or ribs down the length of the box over which sand would run when the worker poured water into the device while rocking it back and forth, the equivalent of shaking a gold pan. A piece of draping canvas helped filter out the gold from the lighter stuff. Rockers were especially useful if the material a miner was working with was partially cemented, meaning sticky clay had to be washed away. A good rocker operator could triple his day’s take over panning, meaning he was up close to what a major general might make.

Still, it was pretty tedious work and the miner was not making the fortune he was dreaming of. A faster production method was called for.

The quickest way to pull gold out of a streambed for one or two men was a sluice running into a rocker. The downside was that you needed a downside. That is, you needed some elevation for water to pick up some speed to wash over the material you were working. Sometimes that meant digging a ditch, which was a lot of work. A sluice was only practical if the bits of gold were fairly large. Gold “dust” would float right out.

A sluice running through a giant could handle 500 yards of gravel a day, compared with that one yard a man with a pan could process. That meant a miner could work material that was a lot less rich and still pull much more gold out in a day.

This sloshing escalation of mining methods could be carried to ends that a single miner couldn’t handle, such as hydraulic mining and large-scale dredging.

No matter the method, the idea behind placer mining was to rinse away the rubble and expose the gold in the remaining sand. It’s a fairly benign operation at the lower end of the scale, but the more material an operation uses the more a streambed or ancient deposit is disturbed. See the aerial below of the windrows of gravel left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.  Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

When you think of a miner, you probably picture some old Gabby Hayes character with a pinned back hat brim crouched over a stream with a pan, dreams of gold glittering in his eye. That’s not a bad picture of a prospector, because most miners (some of whom were also minors) started out that way. Panning for gold is slow and tedious. Shake, shake, shake, rinse, shake, shake, shake, rinse, and repeat until your beard grows down to your waist. Gold flecks are heavier than most of the surrounding material so they sink to the bottom of the pan. A good panner could sift through about a yard of sand and gravel a day. If they turned up $3 or $4 worth of gold, that was excellent. It was about what they might make for a day as, say, a captain in the army in the 1860s, or your average bricklayer in the East.

But miners did not dream of bricklayer wages. They wanted more. That’s why prospectors were typically testing the waters, so to speak, in search of a vein higher upstream. Let’s assume for a moment that they couldn’t find that ledge of quartz, but the quantity of gold in the stream gravel was pretty good. They were stuck with mining the streambed itself or an alluvial fan where water once ran. That’s called “placer mining.” In that case they needed a way to sift more sand and gravel faster in order to have more gold at the end of the day.

Rockers were boxes into which the miner dumped gravel and sand scooped from a stream bottom or alluvial deposit. At the top of the box was a sieve where the larger bits of gravel were screened out. Below that was an incline set up with a series of bumps or ribs down the length of the box over which sand would run when the worker poured water into the device while rocking it back and forth, the equivalent of shaking a gold pan. A piece of draping canvas helped filter out the gold from the lighter stuff. Rockers were especially useful if the material a miner was working with was partially cemented, meaning sticky clay had to be washed away. A good rocker operator could triple his day’s take over panning, meaning he was up close to what a major general might make.

Still, it was pretty tedious work and the miner was not making the fortune he was dreaming of. A faster production method was called for.

The quickest way to pull gold out of a streambed for one or two men was a sluice running into a rocker. The downside was that you needed a downside. That is, you needed some elevation for water to pick up some speed to wash over the material you were working. Sometimes that meant digging a ditch, which was a lot of work. A sluice was only practical if the bits of gold were fairly large. Gold “dust” would float right out.

A sluice running through a giant could handle 500 yards of gravel a day, compared with that one yard a man with a pan could process. That meant a miner could work material that was a lot less rich and still pull much more gold out in a day.

This sloshing escalation of mining methods could be carried to ends that a single miner couldn’t handle, such as hydraulic mining and large-scale dredging.

No matter the method, the idea behind placer mining was to rinse away the rubble and expose the gold in the remaining sand. It’s a fairly benign operation at the lower end of the scale, but the more material an operation uses the more a streambed or ancient deposit is disturbed. See the aerial below of the windrows of gravel left by the Yankee Fork Dredge.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.

This 19th century engraving shows a miner using a rocker box at a streamside. He would dump sand and gravel in the top, then pour water through it to rinse the material.  Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

Aerial view of the gravel windrows left by the Yankee Fork Dredge. The Yankee Fork dumps into the Main Salmon near Sunbeam.

Published on November 07, 2019 04:00