Rick Just's Blog, page 183

October 17, 2019

Old Ninety-Seven is Really 79

A minor piece of Civil War history rests quietly on the grounds of the Idaho Statehouse. It’s a 42-pound seacoast gun, a cannon used during the Civil War at Vicksburg. The “42-pound” is a reference to the weight of the load, not the weight of the gun, which is cast iron. The cannon was forged in 1857. The number 79 is stamped at the top of the muzzle rim. It has been known as “Old Ninety-Seven.”

Old Ninety-Seven seems like an odd nickname for a cannon stamped with the number 79. An article about the artifact that appeared in the June 8, 1941 edition of the Idaho Statesman was headlined “Old ‘Ninety-Seven’ on Statehouse Lawn Symbolizes Past in National Defense.” The piece went on to describe the gun, much as I did in the beginning of this story, except that it stated the number stamped on the muzzle rim was 97. I checked, then rechecked the number. It is 79. Maybe someone glanced at it, then misremembered when they did a story about the gun. It stuck, possibly because the writer confused it with the train song, “The Wreck of Old 97,” which is what you get when you Google Old Ninety-Seven today.

That mystery aside, we know that the statehouse cannon was purchased by Idaho State Treasurer S.A. Hastings and U.S. Senator William Borah and donated to the state in 1910.

The gun has been fired three times while on the statehouse grounds, but never officially. An accidental “firing” took place during prohibition. The barrel of the gun was a handy place to store lunch paper, cigar butts, and other trash. Someone secreted away a bottle of moonshine in there. On a particularly hot day, that resulted in a minor explosion with liquor leaking from the lip of the gun.

In 1936, following an article in the Idaho Statesman that pointed out the gun had never been fired in Idaho (save for the moonshine incident), scalawags set off a charge in the cannon that peppered a nearby parked car with debris, ruining its paint job. Then, in 1946, “kids” lit off a charge of gunpowder in the cannon, which coughed up sticks, rocks, bottles, bottle caps and other debris from its throat. Eventually, groundskeepers plugged the cannon.

In 1942, when the nation was calling on everyone to recycle their metal scrap so it could be used for the war effort, Gov. Chase Clark proposed to scrap the old cannon. He ran into a bit of a buzz saw in the form of a group called the Boise Circle No. 5 of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

The ladies questioned whether the governor even had the authority to scrap the cannon. Mrs. Francis Leonard, who was “instructed to protest for the GAR” according to an article in the Statesman at the time, said, “One of our members, who, in fact, as a small child, sat on Abraham Lincoln’s lap when he was running for President, summed up our position when she declared the governor should also scrap the statue of the late Gov. Frank Steunenberg along with the cannon.” Clark quickly backpedaled and the cannon stayed in place.

Old Ninety-Seven seems like an odd nickname for a cannon stamped with the number 79. An article about the artifact that appeared in the June 8, 1941 edition of the Idaho Statesman was headlined “Old ‘Ninety-Seven’ on Statehouse Lawn Symbolizes Past in National Defense.” The piece went on to describe the gun, much as I did in the beginning of this story, except that it stated the number stamped on the muzzle rim was 97. I checked, then rechecked the number. It is 79. Maybe someone glanced at it, then misremembered when they did a story about the gun. It stuck, possibly because the writer confused it with the train song, “The Wreck of Old 97,” which is what you get when you Google Old Ninety-Seven today.

That mystery aside, we know that the statehouse cannon was purchased by Idaho State Treasurer S.A. Hastings and U.S. Senator William Borah and donated to the state in 1910.

The gun has been fired three times while on the statehouse grounds, but never officially. An accidental “firing” took place during prohibition. The barrel of the gun was a handy place to store lunch paper, cigar butts, and other trash. Someone secreted away a bottle of moonshine in there. On a particularly hot day, that resulted in a minor explosion with liquor leaking from the lip of the gun.

In 1936, following an article in the Idaho Statesman that pointed out the gun had never been fired in Idaho (save for the moonshine incident), scalawags set off a charge in the cannon that peppered a nearby parked car with debris, ruining its paint job. Then, in 1946, “kids” lit off a charge of gunpowder in the cannon, which coughed up sticks, rocks, bottles, bottle caps and other debris from its throat. Eventually, groundskeepers plugged the cannon.

In 1942, when the nation was calling on everyone to recycle their metal scrap so it could be used for the war effort, Gov. Chase Clark proposed to scrap the old cannon. He ran into a bit of a buzz saw in the form of a group called the Boise Circle No. 5 of the Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

The ladies questioned whether the governor even had the authority to scrap the cannon. Mrs. Francis Leonard, who was “instructed to protest for the GAR” according to an article in the Statesman at the time, said, “One of our members, who, in fact, as a small child, sat on Abraham Lincoln’s lap when he was running for President, summed up our position when she declared the governor should also scrap the statue of the late Gov. Frank Steunenberg along with the cannon.” Clark quickly backpedaled and the cannon stayed in place.

Published on October 17, 2019 04:00

October 16, 2019

Robbers' Roost

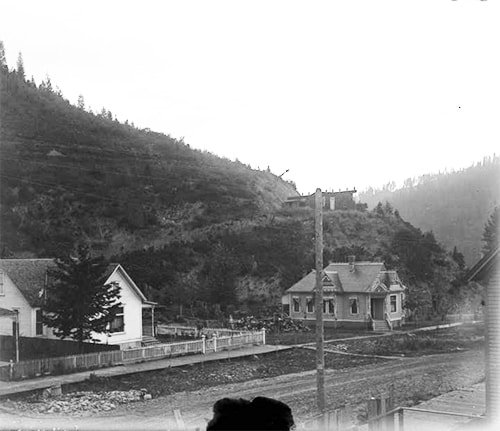

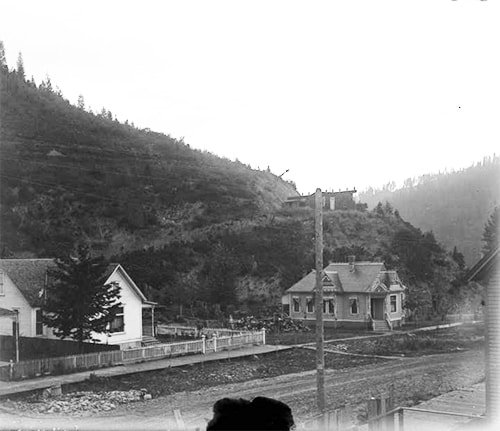

I ran across the photo below in the Idaho State Archives' F.F. Johnson collection of glass plates. The photos in the collection were taken in and around Wallace, this one in 1899. It is the site of Sutherland House then called Robbers' Roost. I don’t know more about it, because I got distracted by the name of the place and failed to follow up on its history. Someone will, no doubt, fill me in.

I wondered how generic “Robbers’ Roost” was. Was it just a handy shortcut to describe any outlaw hideout?

Probably the most famous Robbers’ Roost was in southeastern Utah, the hideout of Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch. There’s an Idaho history connection to that one because some of those infamous outlaws robbed the bank in Montpelier in 1891. The particular gunmen were Butch Cassidy and Eliza Lay. Bob Meeks served as something of a getaway driver, hanging onto the horses while his partners in crime stuffed a gunny sack full of money inside the bank. The irony was that only Meeks was ever arrested and convicted.

There was a Robber’s Roost in Oklahoma, positioned on the highest point of land in that state. Wyoming had one, as well as the famous Hole in the Wall, which served a similar purpose for bandits. And, yes, Idaho had a Robber’s Roost, too. Maybe I should say “has” a Robber’s Roost, since there is a creek and an Idaho Fish and Game Wildlife Management Area near McCammon which both carry the name.

Idaho’s Robber’s Roost was not so much a hideout as a notorious area for stagecoach robberies. During the 1860s stages ran regularly through Portneuf Canyon between Salt Lake City and the mines at Virginia City. The canyon was filled with dense brush providing ample cover for those who would rather pack off gold in a bag or box rather than mine for it. The canyon was surrounded by lava encrusted desert that complicated tracking for those who might want to pursue the robbers. A good summary of the hold-ups there can be found on the Idaho Genealogy website.

There were rumors of another Robbers’ Roost. The August 23, 1870 edition of the Idaho Statesman had an article that said, “It is now generally believed that an organized band of highwaymen exists in the mountains skirting the Snake River, in Idaho and Utah; with headquarters somewhere in the vicinity of Salmon Falls.” That seemed to be a generic use of the term.

Robbers’ Roost was used generically again in 1907 when the Statesman explained why the shortcut road that ran through Boise Barracks to Idaho City was closed. It seems fencing, lumber, firewood, lead pipe and anything that could be carried away from the post was being carried away by people using the road. Captain Dudley, the commandant of the post, closed the road because things “disappeared so steadily as to look almost like the road must lead to a regular robbers’ roost at one end of the line.”

Generic as that reference probably was, the Statesman carried a detailed description of a Robbers’ Roost in northwestern Utah in the May 20, 1906 edition of the paper. A Mr. E.W. Johnson reported on a trip he had just returned from. The stage he was riding stopped to let passengers view a curious structure.

“The man who constructed the building selected a site on a bluff overlooking a stream. The rear portion of the building projects over the bluff, and beneath that portion is an apartment in the nature of a cellar. From this cellar an excavation extends into the hill some 60 feet. This is large enough to shelter a lot of horses and most anything else.

“From the windows there is an unobstructed view up and down the stream for miles and over all the mesa lands on both sides. Nobody could approach the place in daylight without being seen a long distance away.”

So, another Robbers’ Roost. Generic or not, the term paints a picture of an impenetrable hideout where those who found themselves on the wrong side of the law could get away to safety, a common theme in stories of the West if not in fact so common in the real West.

Idaho State Archives F.F. Johnson Collection, P1964-157-20

Idaho State Archives F.F. Johnson Collection, P1964-157-20

I wondered how generic “Robbers’ Roost” was. Was it just a handy shortcut to describe any outlaw hideout?

Probably the most famous Robbers’ Roost was in southeastern Utah, the hideout of Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch. There’s an Idaho history connection to that one because some of those infamous outlaws robbed the bank in Montpelier in 1891. The particular gunmen were Butch Cassidy and Eliza Lay. Bob Meeks served as something of a getaway driver, hanging onto the horses while his partners in crime stuffed a gunny sack full of money inside the bank. The irony was that only Meeks was ever arrested and convicted.

There was a Robber’s Roost in Oklahoma, positioned on the highest point of land in that state. Wyoming had one, as well as the famous Hole in the Wall, which served a similar purpose for bandits. And, yes, Idaho had a Robber’s Roost, too. Maybe I should say “has” a Robber’s Roost, since there is a creek and an Idaho Fish and Game Wildlife Management Area near McCammon which both carry the name.

Idaho’s Robber’s Roost was not so much a hideout as a notorious area for stagecoach robberies. During the 1860s stages ran regularly through Portneuf Canyon between Salt Lake City and the mines at Virginia City. The canyon was filled with dense brush providing ample cover for those who would rather pack off gold in a bag or box rather than mine for it. The canyon was surrounded by lava encrusted desert that complicated tracking for those who might want to pursue the robbers. A good summary of the hold-ups there can be found on the Idaho Genealogy website.

There were rumors of another Robbers’ Roost. The August 23, 1870 edition of the Idaho Statesman had an article that said, “It is now generally believed that an organized band of highwaymen exists in the mountains skirting the Snake River, in Idaho and Utah; with headquarters somewhere in the vicinity of Salmon Falls.” That seemed to be a generic use of the term.

Robbers’ Roost was used generically again in 1907 when the Statesman explained why the shortcut road that ran through Boise Barracks to Idaho City was closed. It seems fencing, lumber, firewood, lead pipe and anything that could be carried away from the post was being carried away by people using the road. Captain Dudley, the commandant of the post, closed the road because things “disappeared so steadily as to look almost like the road must lead to a regular robbers’ roost at one end of the line.”

Generic as that reference probably was, the Statesman carried a detailed description of a Robbers’ Roost in northwestern Utah in the May 20, 1906 edition of the paper. A Mr. E.W. Johnson reported on a trip he had just returned from. The stage he was riding stopped to let passengers view a curious structure.

“The man who constructed the building selected a site on a bluff overlooking a stream. The rear portion of the building projects over the bluff, and beneath that portion is an apartment in the nature of a cellar. From this cellar an excavation extends into the hill some 60 feet. This is large enough to shelter a lot of horses and most anything else.

“From the windows there is an unobstructed view up and down the stream for miles and over all the mesa lands on both sides. Nobody could approach the place in daylight without being seen a long distance away.”

So, another Robbers’ Roost. Generic or not, the term paints a picture of an impenetrable hideout where those who found themselves on the wrong side of the law could get away to safety, a common theme in stories of the West if not in fact so common in the real West.

Idaho State Archives F.F. Johnson Collection, P1964-157-20

Idaho State Archives F.F. Johnson Collection, P1964-157-20

Published on October 16, 2019 04:00

October 15, 2019

One of Many Fine Moscows

Idaho has some lofty place names that would seem to honor much larger and better-known places. Paris is one of those. If you’re expecting an Eiffel Tower, you’re not likely to find one. The name Paris came from the man who platted the town. His name was Frederick Perris. How the name morphed into the spelling that place in France uses is unknown. The U.S. Postal Service is more often the culprit in such cases, having a long history of “correcting” the spelling of post office names.

That happened to a place called Moscow. No, not the one in Idaho. I’ll get to that in a minute. Moscow, Kansas, one of more than 20 Moscows in the U.S., was honoring a Spanish conquistador named Luis de Moscoso, according to a story on the PRI website about the naming of the Moscow cities across the country. For some reason, they wanted to shorten the name to Mosco. A postal person in DC may have thought Kansans simply didn’t know how to spell, so he helpfully added the W, and it officially became Moscow.

None of the Moscows seem ready to claim a Russian connection. The one we know best was allegedly named by Samuel Miles Neff, who owned the first general store there. In that story, Neff had lived in Moscow, Pennsylvania, and Moscow, Iowa, so why not live in another Moscow, this time in Idaho.

There is at least one Idaho town that gets its name, more or less, from the city you would expect. Atlanta was named for a nearby gold discovery that was called Atlanta. It was named after the Battle of Atlanta. News of Sherman’s victory there came about the same time gold was discovered, according to Lalia Boone’s book, Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary.

That happened to a place called Moscow. No, not the one in Idaho. I’ll get to that in a minute. Moscow, Kansas, one of more than 20 Moscows in the U.S., was honoring a Spanish conquistador named Luis de Moscoso, according to a story on the PRI website about the naming of the Moscow cities across the country. For some reason, they wanted to shorten the name to Mosco. A postal person in DC may have thought Kansans simply didn’t know how to spell, so he helpfully added the W, and it officially became Moscow.

None of the Moscows seem ready to claim a Russian connection. The one we know best was allegedly named by Samuel Miles Neff, who owned the first general store there. In that story, Neff had lived in Moscow, Pennsylvania, and Moscow, Iowa, so why not live in another Moscow, this time in Idaho.

There is at least one Idaho town that gets its name, more or less, from the city you would expect. Atlanta was named for a nearby gold discovery that was called Atlanta. It was named after the Battle of Atlanta. News of Sherman’s victory there came about the same time gold was discovered, according to Lalia Boone’s book, Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary.

Published on October 15, 2019 04:00

October 14, 2019

Kook's Tour

There is little neutral ground when it comes to the Three Stooges. You either love them or, not so much. I’m in the not-so-much category, but I was intrigued to learn that their last movie was filmed partly in Idaho.

Larry Fine and Moe Howard started their long and wacky careers as a vaudeville act in 1922 with Shemp Howard as the third leg of the comedy stool. That “leg” was also played by Curly Howard, Joe Besser, and “Curley” Joe Derita over the years, according to the elves at Wikipedia. They made 190 short films that are probably still playing somewhere 24 hours a day.

The Stooges, known for their unique and violent form of slapstick comedy, were trying to launch a new stage in their career in 1969. They were going to do a series of travel “documentaries” set in various locations. Is this where Rick Steves got his idea? Probably not.

During their travels knucklehead antics would ensue. The pilot of the series was called Kook’s Tour, which was a play on the Thomas Cook Travel agency’s Cook’s Tours, recently in the news because they shut down and left travelers stranded. It was shot mostly in Idaho and Wyoming. Filming was not yet complete when Larry Fine suffered a stroke, paralyzing the left side of his body. That killed the idea of a comic travel series.

Someone eventually pulled together the footage they had shot for the pilot and released it as a short movie in 1975. It would be the last film of the Three Stooges’ long career.

Larry Fine and Moe Howard started their long and wacky careers as a vaudeville act in 1922 with Shemp Howard as the third leg of the comedy stool. That “leg” was also played by Curly Howard, Joe Besser, and “Curley” Joe Derita over the years, according to the elves at Wikipedia. They made 190 short films that are probably still playing somewhere 24 hours a day.

The Stooges, known for their unique and violent form of slapstick comedy, were trying to launch a new stage in their career in 1969. They were going to do a series of travel “documentaries” set in various locations. Is this where Rick Steves got his idea? Probably not.

During their travels knucklehead antics would ensue. The pilot of the series was called Kook’s Tour, which was a play on the Thomas Cook Travel agency’s Cook’s Tours, recently in the news because they shut down and left travelers stranded. It was shot mostly in Idaho and Wyoming. Filming was not yet complete when Larry Fine suffered a stroke, paralyzing the left side of his body. That killed the idea of a comic travel series.

Someone eventually pulled together the footage they had shot for the pilot and released it as a short movie in 1975. It would be the last film of the Three Stooges’ long career.

Published on October 14, 2019 04:00

October 13, 2019

Intermountain Institute

The Intermountain Institute in Weiser was a boarding school established in the fall of 1899 to provide children who lived too far from a high school a chance at an education. The school’s motto was “An education and trade for every boy and girl who is willing to work for them.” Children worked five hours a day to help pay for their tuition, board, and room.

About 2,000 students got their education there before the ravages of the Great Depression forced it to close in 1933.

To architects, one feature of the campus buildings is worth note. All but one of the structures, a carriage house, were made of reinforced cast concrete. Concrete was a common building material in early Idaho, but it was used mostly in block form.

The buildings at the Intermountain Institute still had some style. The surfaces of the neo-classical buildings were scored to resemble masonry joints. This can be seen in the photo below of the laundry building under construction.

The Weiser School District used campus buildings until 1967 when a new high school was built. Hooker Hall, a three-story building with a five-story clock tower, became the county museum in the 1980s. In 1994 a fire caused much damage, and the building is still under renovation.

The laundry under construction at the school. Note the concrete exterior.

The laundry under construction at the school. Note the concrete exterior.

About 2,000 students got their education there before the ravages of the Great Depression forced it to close in 1933.

To architects, one feature of the campus buildings is worth note. All but one of the structures, a carriage house, were made of reinforced cast concrete. Concrete was a common building material in early Idaho, but it was used mostly in block form.

The buildings at the Intermountain Institute still had some style. The surfaces of the neo-classical buildings were scored to resemble masonry joints. This can be seen in the photo below of the laundry building under construction.

The Weiser School District used campus buildings until 1967 when a new high school was built. Hooker Hall, a three-story building with a five-story clock tower, became the county museum in the 1980s. In 1994 a fire caused much damage, and the building is still under renovation.

The laundry under construction at the school. Note the concrete exterior.

The laundry under construction at the school. Note the concrete exterior.

Published on October 13, 2019 04:00

October 12, 2019

The Fish Inn

Unique is a word that needs no modifier since it means “unlike anything else.” One thing can’t be more unique than another thing. That doesn’t stop people from sticking words such as “totally,” “really,” “completely,” and “very” in front of unique. Nowadays its meaning is all but synonymous with “unusual.” Language changes and words get watered down. Insert sigh here.

This minor rant comes about because the word “unique” fit the Fish Inn better than any other word. If there was another building remotely like this one, I’m unaware of it. It looked like a fish, more or less. You entered through the gaping mouth. The body of the fish was covered with shingles made to look like scales. The tail, as the only flat part of the fish, became a sign.

The restaurant was built in 1932 for Kenny and Mamie West on Highway 10 near Wolf Lodge Bay. The look of the thing would lead one to believe that they served fish there. They did. Not exclusively, though. For instance, they served adult beverages. In later years you could have a burger and listen to the Normal Fishing Tackle Band. It was once voted one of the best road bars in America by Road and Track magazine.

You could also tack a dollar bill to the ceiling. That not-unique tradition started when a customer proposed to his girlfriend on a dollar bill. She is said to have written “yes,” also on a dollar.

There were something like 4,000 dollar bills tacked to the ceiling at one time. Unfortunately, no one had taken them to the bank when the bills, and the restaurant, burned in 1996.

The Fish Inn, photo by John Margolies. Margolies was an architectural critic who set out to capture iconic vernacular architecture and signs across the United States through his photographs. He loved the cheesy roadside attractions that often made no pretense of skillful design. He is also credited with bringing many historic buildings to the attention of people who might not have recognized their architectural value. As a result, many of them are today on the National Register of Historic Places. The Library of Congress began collecting his images in 2007, and they are made available today to researchers and writers of goofy little books, such as my next one, Symbols, Signs, and Songs, coming out soon.

The Fish Inn, photo by John Margolies. Margolies was an architectural critic who set out to capture iconic vernacular architecture and signs across the United States through his photographs. He loved the cheesy roadside attractions that often made no pretense of skillful design. He is also credited with bringing many historic buildings to the attention of people who might not have recognized their architectural value. As a result, many of them are today on the National Register of Historic Places. The Library of Congress began collecting his images in 2007, and they are made available today to researchers and writers of goofy little books, such as my next one, Symbols, Signs, and Songs, coming out soon.

This minor rant comes about because the word “unique” fit the Fish Inn better than any other word. If there was another building remotely like this one, I’m unaware of it. It looked like a fish, more or less. You entered through the gaping mouth. The body of the fish was covered with shingles made to look like scales. The tail, as the only flat part of the fish, became a sign.

The restaurant was built in 1932 for Kenny and Mamie West on Highway 10 near Wolf Lodge Bay. The look of the thing would lead one to believe that they served fish there. They did. Not exclusively, though. For instance, they served adult beverages. In later years you could have a burger and listen to the Normal Fishing Tackle Band. It was once voted one of the best road bars in America by Road and Track magazine.

You could also tack a dollar bill to the ceiling. That not-unique tradition started when a customer proposed to his girlfriend on a dollar bill. She is said to have written “yes,” also on a dollar.

There were something like 4,000 dollar bills tacked to the ceiling at one time. Unfortunately, no one had taken them to the bank when the bills, and the restaurant, burned in 1996.

The Fish Inn, photo by John Margolies. Margolies was an architectural critic who set out to capture iconic vernacular architecture and signs across the United States through his photographs. He loved the cheesy roadside attractions that often made no pretense of skillful design. He is also credited with bringing many historic buildings to the attention of people who might not have recognized their architectural value. As a result, many of them are today on the National Register of Historic Places. The Library of Congress began collecting his images in 2007, and they are made available today to researchers and writers of goofy little books, such as my next one, Symbols, Signs, and Songs, coming out soon.

The Fish Inn, photo by John Margolies. Margolies was an architectural critic who set out to capture iconic vernacular architecture and signs across the United States through his photographs. He loved the cheesy roadside attractions that often made no pretense of skillful design. He is also credited with bringing many historic buildings to the attention of people who might not have recognized their architectural value. As a result, many of them are today on the National Register of Historic Places. The Library of Congress began collecting his images in 2007, and they are made available today to researchers and writers of goofy little books, such as my next one, Symbols, Signs, and Songs, coming out soon.

Published on October 12, 2019 04:00

October 11, 2019

A Recipe for Public Service

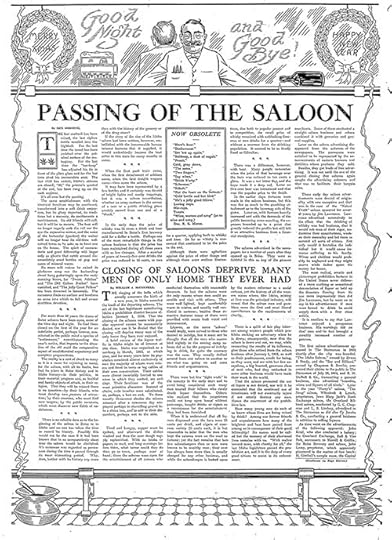

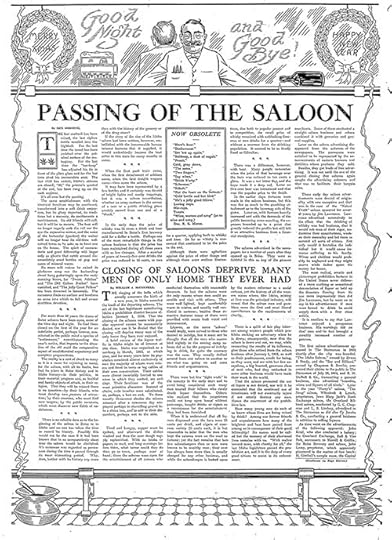

Four years before the national prohibition of liquor, Idaho became a prohibition state on January 1, 1916. The Idaho Statesman seemed to treat it with good humor, lamenting that it “Would deprive many men of the only home they ever had.” (See image)

But there also seemed an element in the paper, as there was in society in general, that had mixed opinions about it. On May 19, 1916, the Statesman reported on an alarming increase in dandelion wine in Boise: “Many owners of dandelion infested lawns have marveled lately at the number of children and grownups who asked permission to help extricate the little golden nuisances ‘for a medicine that mother makes,’ and have been enthusiastically granted permission.

“It has now been learned the manufacture of dandelion wine has been carried on in many Boise homes in large quantities this spring.”

State Chemist Jackson (no first name given) tested some of momma’s medicine and found it came in at 12.6 percent alcohol. He opined that perhaps it should be called “Dandy Lion” wine, because of its alcohol content.

The newspaper extolled the wine’s virtues as a liver medicine, but cautioned that “many a strict prohibition mother is probably making the wine, never dreaming that she is a lawbreaker.”

With those warnings out of the way, the paper proceeded to give a complete recipe for making the wine.

But there also seemed an element in the paper, as there was in society in general, that had mixed opinions about it. On May 19, 1916, the Statesman reported on an alarming increase in dandelion wine in Boise: “Many owners of dandelion infested lawns have marveled lately at the number of children and grownups who asked permission to help extricate the little golden nuisances ‘for a medicine that mother makes,’ and have been enthusiastically granted permission.

“It has now been learned the manufacture of dandelion wine has been carried on in many Boise homes in large quantities this spring.”

State Chemist Jackson (no first name given) tested some of momma’s medicine and found it came in at 12.6 percent alcohol. He opined that perhaps it should be called “Dandy Lion” wine, because of its alcohol content.

The newspaper extolled the wine’s virtues as a liver medicine, but cautioned that “many a strict prohibition mother is probably making the wine, never dreaming that she is a lawbreaker.”

With those warnings out of the way, the paper proceeded to give a complete recipe for making the wine.

Published on October 11, 2019 04:00

October 10, 2019

Biche Creek

We never know where Idaho history will take us. Today’s post starts with TV personality Hasan Minhaj and ends with a French lesson.

Minhaj has a Netflix program called “Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj” that takes a quirky, comedic look at topics of the day. As a supplement to the program he has a YouTube channel where he does the same thing in a shorter format. Recently he posted a program called What's With The Racist Names Of So Many American Places? He pointed out that names can be changed. His focal point was Negro Point in New York City. He mentioned the

Full disclosure, I serve on the Idaho Geographical Names Advisory Committee (IGNAC). We have zero actual power when it comes to place names, but we do review proposals to name features or change existing names in Idaho that USBGN has received. We make our recommendations to the Board of Trustees of the Idaho State Historical Society to approve or deny a proposal based on USBGN

It is difficult to get a name changed. It should be. If names changed frequently it would lead to all kinds of cartographic confusion. There is a process one can follow and you can begin it by following the links above.

Minhaj—remember Minhaj up there in the beginning of this story? —stirred up quite a bit of interest in changing names that are racially offensive. Several groups took on the challenge and began efforts to change some of those names. In today’s internet-dominated world many of them thought gathering names on petitions was a great idea. That isn’t going to work. There is a process that anyone can follow, and it doesn’t involve petitions. It’s not a popularity contest.

Which brings us to the French lesson. One of those petitions included an Idaho place name that some thought offensive, though not racially offensive. Bitch Creek was declared a derogatory name toward women by the petitioner. So far, 60 people nationwide have agreed with the petitioner and are asking for a name change. If they really want to change it, they’ll need to go through the aforementioned process, even if they get a few thousand more names on their petition. (Late breaking news: They have begun the official process)

Bitch Creek starts in Wyoming, flows into Idaho forming the border between Fremont and Teton counties until it converges with Badger Creek, which in turn flows into the North Fork of the Teton River. We could follow its waters to the Pacific Ocean, but you probably get the picture. According to Lalia Boone’s book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary , the original name was Anse de Biche, given to the creek by French trappers. “Anse” can mean “handle” or “cove,” the latter being more likely. “Biche” means “doe” in French.

Biche was corrupted over the years to Bitch. No doubt many have assumed that was meant to be disparaging and many have probably used it in that way. Never mind the canine term, which is the first definition of the word in English.

So, the French trappers who (sort of) named the stream Bitch Creek probably did so innocently. Not so with the name of the nearby Teton Mountains, which were originally Les Trois Tetons, or The Three Breasts. Some petitioner will probably find that offensive, too. But that’s Wyoming’s issue to deal with. Bitch Creek Trestle is part of the Ashton-Tetonia Trail operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation. It crosses 150 feet above Bitch Creek.

Bitch Creek Trestle is part of the Ashton-Tetonia Trail operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation. It crosses 150 feet above Bitch Creek.

Minhaj has a Netflix program called “Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj” that takes a quirky, comedic look at topics of the day. As a supplement to the program he has a YouTube channel where he does the same thing in a shorter format. Recently he posted a program called What's With The Racist Names Of So Many American Places? He pointed out that names can be changed. His focal point was Negro Point in New York City. He mentioned the

Full disclosure, I serve on the Idaho Geographical Names Advisory Committee (IGNAC). We have zero actual power when it comes to place names, but we do review proposals to name features or change existing names in Idaho that USBGN has received. We make our recommendations to the Board of Trustees of the Idaho State Historical Society to approve or deny a proposal based on USBGN

It is difficult to get a name changed. It should be. If names changed frequently it would lead to all kinds of cartographic confusion. There is a process one can follow and you can begin it by following the links above.

Minhaj—remember Minhaj up there in the beginning of this story? —stirred up quite a bit of interest in changing names that are racially offensive. Several groups took on the challenge and began efforts to change some of those names. In today’s internet-dominated world many of them thought gathering names on petitions was a great idea. That isn’t going to work. There is a process that anyone can follow, and it doesn’t involve petitions. It’s not a popularity contest.

Which brings us to the French lesson. One of those petitions included an Idaho place name that some thought offensive, though not racially offensive. Bitch Creek was declared a derogatory name toward women by the petitioner. So far, 60 people nationwide have agreed with the petitioner and are asking for a name change. If they really want to change it, they’ll need to go through the aforementioned process, even if they get a few thousand more names on their petition. (Late breaking news: They have begun the official process)

Bitch Creek starts in Wyoming, flows into Idaho forming the border between Fremont and Teton counties until it converges with Badger Creek, which in turn flows into the North Fork of the Teton River. We could follow its waters to the Pacific Ocean, but you probably get the picture. According to Lalia Boone’s book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary , the original name was Anse de Biche, given to the creek by French trappers. “Anse” can mean “handle” or “cove,” the latter being more likely. “Biche” means “doe” in French.

Biche was corrupted over the years to Bitch. No doubt many have assumed that was meant to be disparaging and many have probably used it in that way. Never mind the canine term, which is the first definition of the word in English.

So, the French trappers who (sort of) named the stream Bitch Creek probably did so innocently. Not so with the name of the nearby Teton Mountains, which were originally Les Trois Tetons, or The Three Breasts. Some petitioner will probably find that offensive, too. But that’s Wyoming’s issue to deal with.

Bitch Creek Trestle is part of the Ashton-Tetonia Trail operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation. It crosses 150 feet above Bitch Creek.

Bitch Creek Trestle is part of the Ashton-Tetonia Trail operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation. It crosses 150 feet above Bitch Creek.

Published on October 10, 2019 04:00

October 9, 2019

Henry Riggs

What’s worthy of getting you a place in Idaho History? Introducing quail to Idaho might do the trick. Henry Chiles Riggs did that in 1871, bringing 56 birds from Missouri. That would be just a footnote, clear down at the bottom of the page in a history book that had little else to talk about.

Okay, how about claiming to be the first citizen of Boise? There were a couple of cabins built where Boise would be, but they were unoccupied, according to Riggs. He claimed that first person honor by pitching a tent and living in it. So, history.

Riggs might have a better chance of making it in print if he brought the first newspaper to Boise, which he did. He didn’t start the Idaho Statesmen, but he went to Portland in 1864 and found some folks who were willing to establish a newspaper in the new town which, by the way, had been named Boise by Henry C. Riggs. Solid footing on the historical footnotes, now.

Riggs was elected to the first Idaho Territorial Legislature from Boise County. He didn’t do a lot in Lewiston during that first session. He just introduced a bill to move the territorial capital to Boise and was instrumental in another one to split Boise County in two. Both passed. Oh, and he suggested the name for the new county. It would be called Ada County, named for his daughter Ada Riggs.

He spent most of his later life at a ranch he bought near Payette. Henry Chiles Riggs died on July 3, 1909, at the Old Soldiers Home in Boise, his place in Idaho history assured.

Okay, how about claiming to be the first citizen of Boise? There were a couple of cabins built where Boise would be, but they were unoccupied, according to Riggs. He claimed that first person honor by pitching a tent and living in it. So, history.

Riggs might have a better chance of making it in print if he brought the first newspaper to Boise, which he did. He didn’t start the Idaho Statesmen, but he went to Portland in 1864 and found some folks who were willing to establish a newspaper in the new town which, by the way, had been named Boise by Henry C. Riggs. Solid footing on the historical footnotes, now.

Riggs was elected to the first Idaho Territorial Legislature from Boise County. He didn’t do a lot in Lewiston during that first session. He just introduced a bill to move the territorial capital to Boise and was instrumental in another one to split Boise County in two. Both passed. Oh, and he suggested the name for the new county. It would be called Ada County, named for his daughter Ada Riggs.

He spent most of his later life at a ranch he bought near Payette. Henry Chiles Riggs died on July 3, 1909, at the Old Soldiers Home in Boise, his place in Idaho history assured.

Published on October 09, 2019 04:00

October 8, 2019

The Aztec Eagles

When you think of air bases in Idaho, Mountain Home Air Force Base comes to mind, and maybe Gowen Field where the Air National Guard has an operation today. The U.S. Army Airbase Pocatello probably isn’t on your radar.

Gowen Field and Mountain Home were airbases during World War II, but so was Army Airbase Pocatello. The Pocatello Regional Airport is located on the site of the old base. That’s where the Mexican Air Force trained.

Wait. What? Yes, Mexico declared war on Germany on May 28, 1942. In 1944 the Mexican government offered an Air Force squadron to President Roosevelt to support the war effort in the Pacific. That’s when the 201st Mexican Expeditionary Air Force Squadron of Mexico moved to the U.S. for training.

The squadron called themselves Aztec Eagles. They trained first at Randolph Field in San Antonio, where they were given medical exams and received testing for flight and weapons proficiency. Next, the squadron went to the army base at Pocatello to receive specialty training in each man’s area of expertise, such as armament, communication, or engineering. They finished their training at Gunnery School at Harlingen, Texas.

Thirty-eight pilots and more than 300 support personnel from the Mexican Expeditionary Air Force flew into Pocatello for three months of training in 1944. The Mexicans were surprised to meet female pilots while they were there. The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) shuttled airplanes from one base to another. The Mexican Air Force had no equivalent, but they soon learned to respect the skills of the women.

The Aztec Eagles joined the war effort in the Philippines in June, 1945 as part of MacArthur’s promised return. They flew 96 combat missions, dropping some 1500 bombs on Luzon and Formosa, helping to drive the Japanese from those islands.

While fighting in the Philippines the Aztec Eagles lost five pilots, three who ran out of fuel over the ocean, one who crashed, and one who was shot down.

In November 1945, the Aztec Eagles returned to Mexico and were welcomed home with a military parade, honoring the first Mexican troops to ever participate in military combat overseas.

U.S. Air Force, Philippine Army and Mexican Air Force members admire the representation of "Panchito Pistoles," the mascot of the Escuadrón 201, painted on a wing fragment of a Japanese aircraft. "Panchito Pistoles" starred in the Walt Disney film "The Three Caballeros" and was adopted by their unit. (US Army Air Force photo)

U.S. Air Force, Philippine Army and Mexican Air Force members admire the representation of "Panchito Pistoles," the mascot of the Escuadrón 201, painted on a wing fragment of a Japanese aircraft. "Panchito Pistoles" starred in the Walt Disney film "The Three Caballeros" and was adopted by their unit. (US Army Air Force photo)  The main gate of Army Airbase Pocatello.

The main gate of Army Airbase Pocatello.

Gowen Field and Mountain Home were airbases during World War II, but so was Army Airbase Pocatello. The Pocatello Regional Airport is located on the site of the old base. That’s where the Mexican Air Force trained.

Wait. What? Yes, Mexico declared war on Germany on May 28, 1942. In 1944 the Mexican government offered an Air Force squadron to President Roosevelt to support the war effort in the Pacific. That’s when the 201st Mexican Expeditionary Air Force Squadron of Mexico moved to the U.S. for training.

The squadron called themselves Aztec Eagles. They trained first at Randolph Field in San Antonio, where they were given medical exams and received testing for flight and weapons proficiency. Next, the squadron went to the army base at Pocatello to receive specialty training in each man’s area of expertise, such as armament, communication, or engineering. They finished their training at Gunnery School at Harlingen, Texas.

Thirty-eight pilots and more than 300 support personnel from the Mexican Expeditionary Air Force flew into Pocatello for three months of training in 1944. The Mexicans were surprised to meet female pilots while they were there. The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) shuttled airplanes from one base to another. The Mexican Air Force had no equivalent, but they soon learned to respect the skills of the women.

The Aztec Eagles joined the war effort in the Philippines in June, 1945 as part of MacArthur’s promised return. They flew 96 combat missions, dropping some 1500 bombs on Luzon and Formosa, helping to drive the Japanese from those islands.

While fighting in the Philippines the Aztec Eagles lost five pilots, three who ran out of fuel over the ocean, one who crashed, and one who was shot down.

In November 1945, the Aztec Eagles returned to Mexico and were welcomed home with a military parade, honoring the first Mexican troops to ever participate in military combat overseas.

U.S. Air Force, Philippine Army and Mexican Air Force members admire the representation of "Panchito Pistoles," the mascot of the Escuadrón 201, painted on a wing fragment of a Japanese aircraft. "Panchito Pistoles" starred in the Walt Disney film "The Three Caballeros" and was adopted by their unit. (US Army Air Force photo)

U.S. Air Force, Philippine Army and Mexican Air Force members admire the representation of "Panchito Pistoles," the mascot of the Escuadrón 201, painted on a wing fragment of a Japanese aircraft. "Panchito Pistoles" starred in the Walt Disney film "The Three Caballeros" and was adopted by their unit. (US Army Air Force photo)  The main gate of Army Airbase Pocatello.

The main gate of Army Airbase Pocatello.

Published on October 08, 2019 04:00