Rick Just's Blog, page 187

September 7, 2019

Paving the Way

Idahoans have been griping about the state of our streets and roads since the first one was built in the territory. Nothing gets a driver’s temper up than hitting a good, deep pothole. We expect our streets to be smooth and flat. Automobiles and paved streets are so closely associated that it is fair to ask, which came first? The chic.. No, cars or pavement?

Long before an automobile rolled into town the Lewiston Teller was asking, “Why not bond the city and pave the streets?” in an 1891 editorial complaining about uneven grading and indiscriminate dumping of dirt on city streets. The city seems to have gotten around to its first major paving project in 1900.

In Boise, the city council decided to pave some streets in 1897. Their first bold vision included asphalt on “Front from Twelfth to Tenth, Tenth from Front to Idaho, Idaho from Tenth to Seventh, Main from Tenth to Fifth, Ninth from Grove to Bannock, Eighth from Grove to Jefferson, Seventh from Grove to Idaho, Jefferson from Grove to Sixth, the alley between Main and Grove from Tenth to Seventh.”

When the project began, though, they had whittled it down to paving five blocks on Main Street.

Why pave when there weren’t any cars? Wagons, horses, and bicycles used those streets, which were perpetually either dusty or muddy. But paving improved more than just the streets, as suggested by a congratulatory article in the Caldwell Record that July. “Main Street is being paved and it is certainly to the credit of its citizens that they are determined to retrieve the city from the mud and dust to which it has been subject and to make the capital of Idaho worthy of the name Boise the beautiful. It is to be remarked that trees and lawns are now bright and green and free of dust, something never before known at mid-summer in Boise.”

Trees free of dust were due to the paving project, and an aggressive street watering regimen adopted at the same time on the remaining dirt roads.

By 1910, when the photo below of paving on Fairview Avenue in Boise was taken, cars were beginning to be part of the mix.

Long before an automobile rolled into town the Lewiston Teller was asking, “Why not bond the city and pave the streets?” in an 1891 editorial complaining about uneven grading and indiscriminate dumping of dirt on city streets. The city seems to have gotten around to its first major paving project in 1900.

In Boise, the city council decided to pave some streets in 1897. Their first bold vision included asphalt on “Front from Twelfth to Tenth, Tenth from Front to Idaho, Idaho from Tenth to Seventh, Main from Tenth to Fifth, Ninth from Grove to Bannock, Eighth from Grove to Jefferson, Seventh from Grove to Idaho, Jefferson from Grove to Sixth, the alley between Main and Grove from Tenth to Seventh.”

When the project began, though, they had whittled it down to paving five blocks on Main Street.

Why pave when there weren’t any cars? Wagons, horses, and bicycles used those streets, which were perpetually either dusty or muddy. But paving improved more than just the streets, as suggested by a congratulatory article in the Caldwell Record that July. “Main Street is being paved and it is certainly to the credit of its citizens that they are determined to retrieve the city from the mud and dust to which it has been subject and to make the capital of Idaho worthy of the name Boise the beautiful. It is to be remarked that trees and lawns are now bright and green and free of dust, something never before known at mid-summer in Boise.”

Trees free of dust were due to the paving project, and an aggressive street watering regimen adopted at the same time on the remaining dirt roads.

By 1910, when the photo below of paving on Fairview Avenue in Boise was taken, cars were beginning to be part of the mix.

Published on September 07, 2019 04:00

September 6, 2019

Murder in the Craters

Countless men from lands far away came to Idaho to seek their fortune in the late 19th and early 20th century. Such was the case with two men from Austria, Dan Eliuk and Fred Kobyluik. They came to the Gem State in 1924 by way of Utah. While mining near Park City they met a young man from Idaho who said that he could get them jobs working on a ranch near his hometown of Carey. It sounded good to the Austrians, so they withdrew their savings from a local bank, piled in Kobyluik’s car with the Idaho native, and set out for a western adventure.

On their way to Carey the three stayed overnight at a hotel in Paul. Dan Eliuk would later say that he had noticed the young man who had promised them jobs sign his name as I. Hart on the guest register. That was a little strange, because his name was Arley Latham, a name that would soon be infamous.

The next day Latham had them stop the car near the boundary of Craters of the Moon which had become a national monument just a couple of weeks earlier on June 15. The terrain was black rocks and blacker rocks and crevices with more rocks scattered around. Even so, Latham told Dan Eliuk to stay with the car while he and Kobyluik headed out on foot just a short distance to the ranch which was over a little rise of lava rocks.

With Eliuk waiting behind them the men set out across the rugged landscape, soon disappearing over the ridge. About 15 minutes later Eliuk heard three shots. Not long after Latham came back to get him, saying that Kobyluik had gone on ahead to the ranch and would meet them there. What about the shots? Rabbits, said Latham.

So, Dan and Arley—I’m using first names now because I’m tired typing those Austrian surnames—set out for the ranch. When they got there Fred wasn’t in evidence. Neither was the ranch manager. The two made themselves at home and waited for someone to show up.

The night passed without the arrival of anyone else. Arley seemed unconcerned and suggested a walk in the lavas to Dan. He declined. How about a trip to Fish Lake? Dan wasn’t interested. Dan was interested only in finding a phone, which he did. He called authorities in Hailey and told them about the worrisome disappearance of his partner.

A search party was put together. Arley joined the men in the search for Fred. When they found no sign of the man, Arley suddenly changed his story. He said that Dan had killed Fred. That seemed a little too convenient to the sheriff. He and a deputy questioned Arley vigorously, resulting in another story coming forth.

Arley Latham had planned all along to murder Fred, the man with the cash. When they were out of sight of Dan and the car, he shot Fred in the back. Fred turned toward Arley who shot him in the left eye and a third time in the chest. Now, it should have been a simple thing to lean over and remove the dead man’s wallet. This was Craters of the Moon, though. When Fred fell, he fell into one of thousands of cracks in the lava rock. He fell in such a way as to solidly wedge the wallet between his body and the wall of the crevice.

Latham was able to stretch his arm down into the crack in the lava and rip the dead man’s clothing enough that he got $5 for his efforts. He gave up and kicked some rocks over the body so it would be more difficult to see, then went back to the car to retrieve Dan.

Arley Latham confessed to the sheriff and to the editor of the Arco Advertiser, C.A. Bottolfsen, saying he had planned to kill both of the Austrians and make off with their car and money. They were foreigners. Who would miss them?

Justice was swift. The murder had taken place on July 1. Latham was arrested and confessed late on July 2. He was in prison on August 8, serving a sentence of 25 years to life for the murder of Fred Kobyluik.

But Latham would stay in prison only 16 years, ultimately to be set free by one of the men he had confessed to. C.A. Bottolfsen had become governor. He pardoned Latham not because the justice system had made a mistake, but because Arley Latham was dying from tuberculosis. He was released on the 13th of November 1940 on the recommendation of the prison doctor who said he didn’t have long to live.

The story could end there, all of us assuming that Latham passed away unnoticed shortly after his release. Actually, he married not long after his release, in February 1942. He was soon divorced and remarried in 1948. That marriage lasted until 1958. Latham passed away in Boise in 1963 at the age of 60. What he did for a living during the 23 years after his release is unknown. In the obituary for Latham’s father it mentioned a grandchild. Since Latham was an only child it seems likely the grandchild was the offspring from one of his marriages.

Latham is buried at the Dry Creek Cemetery in Boise. Fred Kobyluik’s body was retrieved from the crevice by the county coroner and buried a short distance away.

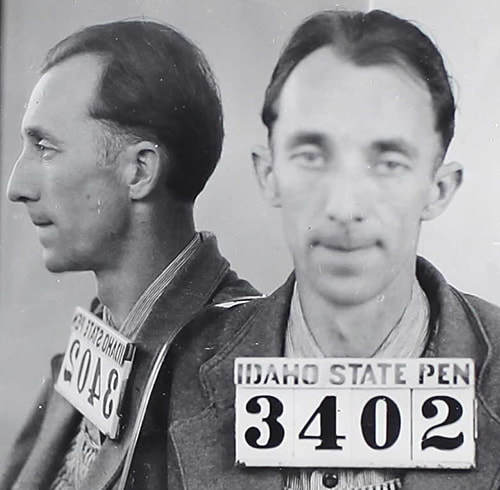

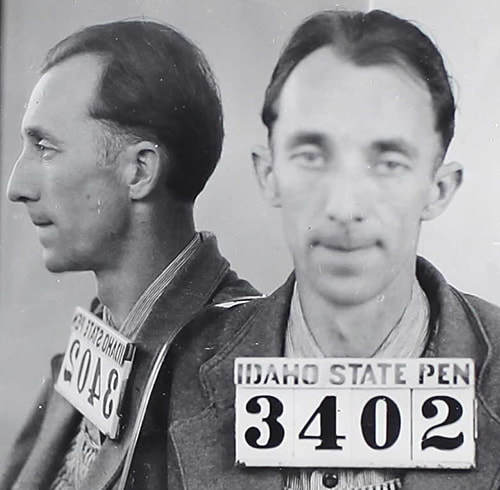

Mug shot of Arley Latham, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Mug shot of Arley Latham, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

On their way to Carey the three stayed overnight at a hotel in Paul. Dan Eliuk would later say that he had noticed the young man who had promised them jobs sign his name as I. Hart on the guest register. That was a little strange, because his name was Arley Latham, a name that would soon be infamous.

The next day Latham had them stop the car near the boundary of Craters of the Moon which had become a national monument just a couple of weeks earlier on June 15. The terrain was black rocks and blacker rocks and crevices with more rocks scattered around. Even so, Latham told Dan Eliuk to stay with the car while he and Kobyluik headed out on foot just a short distance to the ranch which was over a little rise of lava rocks.

With Eliuk waiting behind them the men set out across the rugged landscape, soon disappearing over the ridge. About 15 minutes later Eliuk heard three shots. Not long after Latham came back to get him, saying that Kobyluik had gone on ahead to the ranch and would meet them there. What about the shots? Rabbits, said Latham.

So, Dan and Arley—I’m using first names now because I’m tired typing those Austrian surnames—set out for the ranch. When they got there Fred wasn’t in evidence. Neither was the ranch manager. The two made themselves at home and waited for someone to show up.

The night passed without the arrival of anyone else. Arley seemed unconcerned and suggested a walk in the lavas to Dan. He declined. How about a trip to Fish Lake? Dan wasn’t interested. Dan was interested only in finding a phone, which he did. He called authorities in Hailey and told them about the worrisome disappearance of his partner.

A search party was put together. Arley joined the men in the search for Fred. When they found no sign of the man, Arley suddenly changed his story. He said that Dan had killed Fred. That seemed a little too convenient to the sheriff. He and a deputy questioned Arley vigorously, resulting in another story coming forth.

Arley Latham had planned all along to murder Fred, the man with the cash. When they were out of sight of Dan and the car, he shot Fred in the back. Fred turned toward Arley who shot him in the left eye and a third time in the chest. Now, it should have been a simple thing to lean over and remove the dead man’s wallet. This was Craters of the Moon, though. When Fred fell, he fell into one of thousands of cracks in the lava rock. He fell in such a way as to solidly wedge the wallet between his body and the wall of the crevice.

Latham was able to stretch his arm down into the crack in the lava and rip the dead man’s clothing enough that he got $5 for his efforts. He gave up and kicked some rocks over the body so it would be more difficult to see, then went back to the car to retrieve Dan.

Arley Latham confessed to the sheriff and to the editor of the Arco Advertiser, C.A. Bottolfsen, saying he had planned to kill both of the Austrians and make off with their car and money. They were foreigners. Who would miss them?

Justice was swift. The murder had taken place on July 1. Latham was arrested and confessed late on July 2. He was in prison on August 8, serving a sentence of 25 years to life for the murder of Fred Kobyluik.

But Latham would stay in prison only 16 years, ultimately to be set free by one of the men he had confessed to. C.A. Bottolfsen had become governor. He pardoned Latham not because the justice system had made a mistake, but because Arley Latham was dying from tuberculosis. He was released on the 13th of November 1940 on the recommendation of the prison doctor who said he didn’t have long to live.

The story could end there, all of us assuming that Latham passed away unnoticed shortly after his release. Actually, he married not long after his release, in February 1942. He was soon divorced and remarried in 1948. That marriage lasted until 1958. Latham passed away in Boise in 1963 at the age of 60. What he did for a living during the 23 years after his release is unknown. In the obituary for Latham’s father it mentioned a grandchild. Since Latham was an only child it seems likely the grandchild was the offspring from one of his marriages.

Latham is buried at the Dry Creek Cemetery in Boise. Fred Kobyluik’s body was retrieved from the crevice by the county coroner and buried a short distance away.

Mug shot of Arley Latham, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Mug shot of Arley Latham, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on September 06, 2019 04:00

September 5, 2019

A Moving Panorama

What did we do before the Internet for entertainment? Oh yeah, TV. Oh, and movies, and before that, moving panoramas, and before… Wait, moving panoramas?

The term “moving panorama” has often been used as a metaphor, as in “the street scene was a moving panorama,” or “the moving panorama of life.”

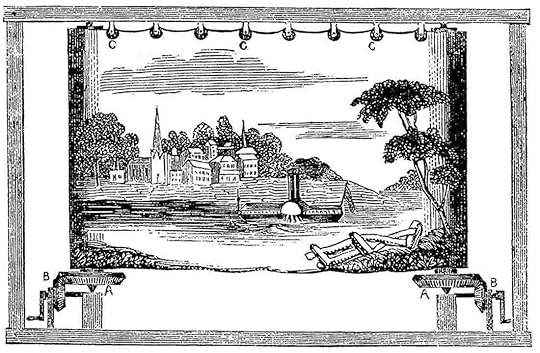

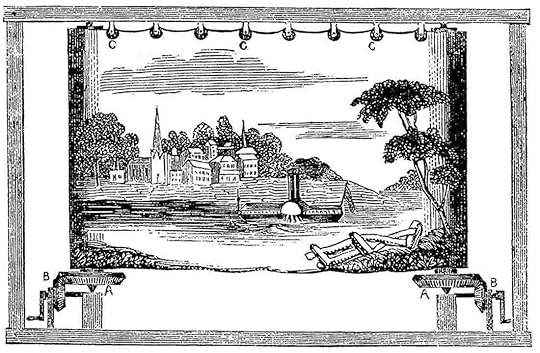

What is lost to most of us is that moving panoramas were a common form of entertainment in the 19th century. Picture (as in the picture) a continuous canvas scene with each end rolled around large spools. Cranking and rolling one spool would scroll the painting past an audience. The paintings themselves were usually not the whole show. There would be a narrator and perhaps music to go along with the narration. Often the story would be essentially a road trip or travelogue describing what the narrator saw on his adventure.

The first reference to one I found in an Idaho paper was the mention of Pendar’s Panorama of the War in the Nov. 21, 1863 edition of the Boise News, which was a short-lived Idaho City newspaper.

In 1865 the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman noted that “A Panorama of the civil war in America, ancient scenes of the Bible, and a large number of miscellaneous and running comic views, will be exhibited in this city to-night in the canvas spread on the corner opposite the Statesman office. In connection with it is a sword-swallower, stone-eater and snake charmer.”

Artemus Ward, arguably the first ever stand-up comic, travelled the world with a panorama that was a parody of panoramas.

The Idaho County Free Press in Grangeville trumpeted a panorama on September 11, 1891. “There will be a magic lantern exhibition at Grange hall, Tuesday evening September 22, showing views of Gettysburg, historic places of America, the Johnstown disaster, views along the vine-clad Rhine, Irish scenery, an ocean steamer at sea, etc, etc. There will also be recitations of famous poems, and an interesting lecture to accompany the panorama.”

A competing form of entertainment, and another presage of motion pictures, was the viewing of projected stereoscopic photos. An article or ad—it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference—in the Idaho City World of October 13, 1866, touted the superiority of this new amusement over moving panoramas with a series of stacked headlines:

New Exhibition

OF THE

STEREOSCOPTICON

And California and Nevada Scenery

Produced by the wonderful and celebrated

MAGNESIUM LIGHTS

Will exhibit at the

JENNY LIND THEATER, IDAHO CITY

The term “moving panorama” has often been used as a metaphor, as in “the street scene was a moving panorama,” or “the moving panorama of life.”

What is lost to most of us is that moving panoramas were a common form of entertainment in the 19th century. Picture (as in the picture) a continuous canvas scene with each end rolled around large spools. Cranking and rolling one spool would scroll the painting past an audience. The paintings themselves were usually not the whole show. There would be a narrator and perhaps music to go along with the narration. Often the story would be essentially a road trip or travelogue describing what the narrator saw on his adventure.

The first reference to one I found in an Idaho paper was the mention of Pendar’s Panorama of the War in the Nov. 21, 1863 edition of the Boise News, which was a short-lived Idaho City newspaper.

In 1865 the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman noted that “A Panorama of the civil war in America, ancient scenes of the Bible, and a large number of miscellaneous and running comic views, will be exhibited in this city to-night in the canvas spread on the corner opposite the Statesman office. In connection with it is a sword-swallower, stone-eater and snake charmer.”

Artemus Ward, arguably the first ever stand-up comic, travelled the world with a panorama that was a parody of panoramas.

The Idaho County Free Press in Grangeville trumpeted a panorama on September 11, 1891. “There will be a magic lantern exhibition at Grange hall, Tuesday evening September 22, showing views of Gettysburg, historic places of America, the Johnstown disaster, views along the vine-clad Rhine, Irish scenery, an ocean steamer at sea, etc, etc. There will also be recitations of famous poems, and an interesting lecture to accompany the panorama.”

A competing form of entertainment, and another presage of motion pictures, was the viewing of projected stereoscopic photos. An article or ad—it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference—in the Idaho City World of October 13, 1866, touted the superiority of this new amusement over moving panoramas with a series of stacked headlines:

New Exhibition

OF THE

STEREOSCOPTICON

And California and Nevada Scenery

Produced by the wonderful and celebrated

MAGNESIUM LIGHTS

Will exhibit at the

JENNY LIND THEATER, IDAHO CITY

Published on September 05, 2019 04:00

September 4, 2019

Those Famous KGEM Announcers

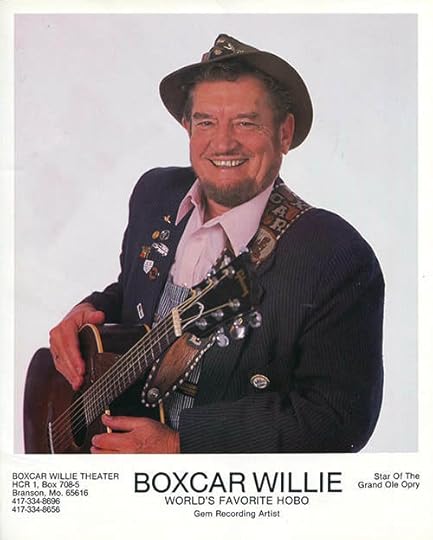

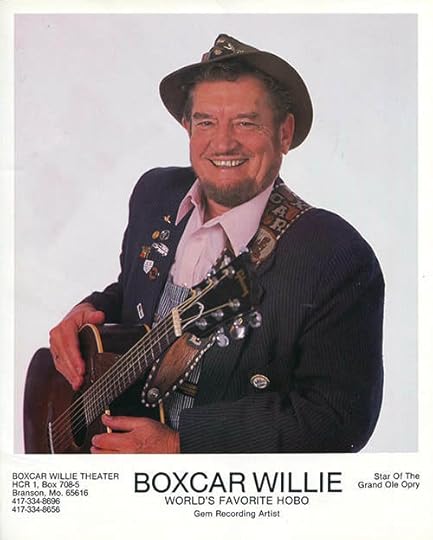

KGEM radio in Boise was a country western station for four or five decades. Dozens, if not hundreds, of radio announcers worked there over the years. Two of them became famous. Well, three, if you think writing this column makes me famous. No? Okay, then, just two.

Larry Lujack grew up in Caldwell and graduated from Caldwell High School where he was an all-state quarterback. He went by Larry Blankenburg in those days. He changed to the nom de plume of Larry Lujack when he started working on Caldwell’s KCID radio in 1958.

The exact dates that Lujack worked on KGEM are uncertain, sometime between 1959 and 1963. That he was fired by station manager Bob Wiesenberger is more certain. Wiesenberger was not shy about telling the story. Lujack, always a little on the edge of decorum, allegedly made a joke on the air about the sheep he could see as he looked out the studio window. The joke involved Wiesenberger’s wife. Bob was not amused. Exit Lujack.

The dee jay eventually landed on his feet, ending up top-40 royalty in Chicago for 20 years on WLS. He wrote a book, which included the above-mentioned story, called Superjock, and was inducted into a couple of national broadcasting halls of fame. Lujack, who attended the College of Idaho and Washington State University, passed away in 2013 at the age of 73.

The other star to come out of KGEM was Marty Martin. He was probably the most famous country western star you never heard of.

Martin started working on KGEM in about 1963 and was on the air until 1970. He was all over the valley with remote broadcasts for the station and with his own dance band. He emceed everything that came along. For a time he hosted an Idaho talent show on KTVB called—get ready to cringe—“Idahoedown.”

In 1964 Martin was honored by the Grand Ole Opry as “Mr. Deejay USA.” He made several trips back to Tennessee and became friends with Willie Nelson. I’m name dropping here, because it was that name—Willie—that Martin eventually took as his stage name. He often told the story of driving along next to a rolling freight train and spotting a hobo who looked like Willie Nelson riding in one of the boxcars. The phrase Boxcar Willie came to mind. As soon as he could he put that in a song with the same title, bringing it out in 1970. It didn’t sell all that well, but it got some notice locally, and he adopted the name and persona.

Do you remember “The Gong Show”? Well, irritating as that memory might be, it was a break for the newly named Boxcar Willie when he won the competition. He sang well and dressed as a down-and-out hobo to complete the look, which fit the show perfectly.

Europe loved Boxcar Willie better than this country did. In the late 70s you’d see occasional TV ads for his albums touting his European popularity. That didn’t immediately translate into success in the USA, but he did have ten records hit the country Hot 100 between 1980 and 1984. The most successful of them was a song called “Bad News” that made it to number 36.

In 1981 he became a member of the Grand Ole Opry. Then, in 1985, he did something that was probably considered crazy at the time. He purchased a theater in Branson, Missouri and began performing there for ever-increasing crowds. He was one of the first to recognize the potential of Branson as a country music venue.

Boxcar Willie performed regularly Branson until his death there at age 67 in 1999.

Larry Lujack grew up in Caldwell and graduated from Caldwell High School where he was an all-state quarterback. He went by Larry Blankenburg in those days. He changed to the nom de plume of Larry Lujack when he started working on Caldwell’s KCID radio in 1958.

The exact dates that Lujack worked on KGEM are uncertain, sometime between 1959 and 1963. That he was fired by station manager Bob Wiesenberger is more certain. Wiesenberger was not shy about telling the story. Lujack, always a little on the edge of decorum, allegedly made a joke on the air about the sheep he could see as he looked out the studio window. The joke involved Wiesenberger’s wife. Bob was not amused. Exit Lujack.

The dee jay eventually landed on his feet, ending up top-40 royalty in Chicago for 20 years on WLS. He wrote a book, which included the above-mentioned story, called Superjock, and was inducted into a couple of national broadcasting halls of fame. Lujack, who attended the College of Idaho and Washington State University, passed away in 2013 at the age of 73.

The other star to come out of KGEM was Marty Martin. He was probably the most famous country western star you never heard of.

Martin started working on KGEM in about 1963 and was on the air until 1970. He was all over the valley with remote broadcasts for the station and with his own dance band. He emceed everything that came along. For a time he hosted an Idaho talent show on KTVB called—get ready to cringe—“Idahoedown.”

In 1964 Martin was honored by the Grand Ole Opry as “Mr. Deejay USA.” He made several trips back to Tennessee and became friends with Willie Nelson. I’m name dropping here, because it was that name—Willie—that Martin eventually took as his stage name. He often told the story of driving along next to a rolling freight train and spotting a hobo who looked like Willie Nelson riding in one of the boxcars. The phrase Boxcar Willie came to mind. As soon as he could he put that in a song with the same title, bringing it out in 1970. It didn’t sell all that well, but it got some notice locally, and he adopted the name and persona.

Do you remember “The Gong Show”? Well, irritating as that memory might be, it was a break for the newly named Boxcar Willie when he won the competition. He sang well and dressed as a down-and-out hobo to complete the look, which fit the show perfectly.

Europe loved Boxcar Willie better than this country did. In the late 70s you’d see occasional TV ads for his albums touting his European popularity. That didn’t immediately translate into success in the USA, but he did have ten records hit the country Hot 100 between 1980 and 1984. The most successful of them was a song called “Bad News” that made it to number 36.

In 1981 he became a member of the Grand Ole Opry. Then, in 1985, he did something that was probably considered crazy at the time. He purchased a theater in Branson, Missouri and began performing there for ever-increasing crowds. He was one of the first to recognize the potential of Branson as a country music venue.

Boxcar Willie performed regularly Branson until his death there at age 67 in 1999.

Published on September 04, 2019 04:00

September 3, 2019

A Photo Lineup

It’s fun looking at old pictures. You get to daydream about what the lives of the people in the photos would have been like. You could look at this one from 1907, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, and wonder what these nattily dressed men were doing standing around in front of a formal carriage. Politicians, maybe? Land owners on an inspection tour?

What about that guy in the center, with the number 3 written across his shoulder? Is he looking relaxed with his hands folded behind his back?

We don’t have to wonder what was up, because the Historical Society has provided us with a handy key to who was in the picture. Man number one is Warden E.L. Whitney of the Idaho State Penitentiary. The number two man is Deputy Bartell, a trial witness for the State of Colorado. Man number four is an Idaho prison guard, last name Ackley. Number five is Edgar Hawley, and number six is Detective Charles Siringo of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

Oh, and number three? Harry Orchard. He wasn’t just standing at ease with his hands behind his back. They were likely in handcuffs. Orchard was convicted of setting the bomb trap that killed ex-Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. The picture was likely taken during the famous Haywood trial, where Orchard was a key witness.

What about that guy in the center, with the number 3 written across his shoulder? Is he looking relaxed with his hands folded behind his back?

We don’t have to wonder what was up, because the Historical Society has provided us with a handy key to who was in the picture. Man number one is Warden E.L. Whitney of the Idaho State Penitentiary. The number two man is Deputy Bartell, a trial witness for the State of Colorado. Man number four is an Idaho prison guard, last name Ackley. Number five is Edgar Hawley, and number six is Detective Charles Siringo of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

Oh, and number three? Harry Orchard. He wasn’t just standing at ease with his hands behind his back. They were likely in handcuffs. Orchard was convicted of setting the bomb trap that killed ex-Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. The picture was likely taken during the famous Haywood trial, where Orchard was a key witness.

Published on September 03, 2019 04:00

September 2, 2019

Idaho's Famous Dance... Sorta

“You put your right foot…” And that’s about all you need to get your mind humming the “Hokey Pokey” if you’ve heard it even once. The rest of the song is a simultaneous instruction manual for how to do the dance.

You would think the origins of such a song would be fairly easy to trace. And you’d be right. The trouble is, there are multiple origins.

According to a 2018 article written for “Mental Floss” by Eddie Deezen, there were similar songs popping up all over the world, nearly at the same time. That would be called going viral, today, but this was back in the 1940s. Were all the similar songs original, or had the catchy tune earwormed into composer’s heads and come out later as their own creations?

There was much haggling among those who had written songs called “The Hoey Oka” (1940) and “The Hokey Cokey” (1942), both published in the United Kingdom. Another composer was entertaining the troops with his “Hokey Pokey” in wartime London.

Those British songs were news to a couple of composers in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1946, when they came out with their dance tune called, “The Hokey Pokey Dance.”

Though similar, none of those songs was quite the one you’ve likely heard. That one came out of Sun Valley, which is why we’re rattling on about a song that you’ve never pulled up on Spotify (note: you could).

Charles Mack, Taft Baker, and Larry Laprise, known as The Sun Valley Trio, played “The Hokey Pokey” for skiers at Sun Valley in 1949. The Scranton composers sued, but Laprise won the court case and the right to claim “The Hokey Pokey” was his. The version you are likely familiar with was recorded and released by Ray Anthony’s Orchestra in 1953. It went to number 13 on the charts. The flip side was also a hit, called “The Bunny Hop.”

So, there’s a solid Idaho connection to “The Hokey Pokey” but don’t start moving those celebrating feet, yet. There’s more to the story. Even those early 40s versions were about 114 years after the fact. A similar dance with similar instructions was publish in 1826 in Robert Chambers's Popular Rhymes of Scotland. Speculation is that the traditional folk dance had been around since the 1700s. The song, or something like it, showed up in 1857 in the United States when a couple of sisters from England were visiting New Hampshire and passed along the steps to locals there. You know the steps. “You put your right foot…” "You put your right foot.." in your ski binding. After that, you might do the Hokey Pokey. This picture was taken in the 1940s at Sun Valley, about the same time everyone was dancing the Hokey Pokey in the lodge. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

"You put your right foot.." in your ski binding. After that, you might do the Hokey Pokey. This picture was taken in the 1940s at Sun Valley, about the same time everyone was dancing the Hokey Pokey in the lodge. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

You would think the origins of such a song would be fairly easy to trace. And you’d be right. The trouble is, there are multiple origins.

According to a 2018 article written for “Mental Floss” by Eddie Deezen, there were similar songs popping up all over the world, nearly at the same time. That would be called going viral, today, but this was back in the 1940s. Were all the similar songs original, or had the catchy tune earwormed into composer’s heads and come out later as their own creations?

There was much haggling among those who had written songs called “The Hoey Oka” (1940) and “The Hokey Cokey” (1942), both published in the United Kingdom. Another composer was entertaining the troops with his “Hokey Pokey” in wartime London.

Those British songs were news to a couple of composers in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1946, when they came out with their dance tune called, “The Hokey Pokey Dance.”

Though similar, none of those songs was quite the one you’ve likely heard. That one came out of Sun Valley, which is why we’re rattling on about a song that you’ve never pulled up on Spotify (note: you could).

Charles Mack, Taft Baker, and Larry Laprise, known as The Sun Valley Trio, played “The Hokey Pokey” for skiers at Sun Valley in 1949. The Scranton composers sued, but Laprise won the court case and the right to claim “The Hokey Pokey” was his. The version you are likely familiar with was recorded and released by Ray Anthony’s Orchestra in 1953. It went to number 13 on the charts. The flip side was also a hit, called “The Bunny Hop.”

So, there’s a solid Idaho connection to “The Hokey Pokey” but don’t start moving those celebrating feet, yet. There’s more to the story. Even those early 40s versions were about 114 years after the fact. A similar dance with similar instructions was publish in 1826 in Robert Chambers's Popular Rhymes of Scotland. Speculation is that the traditional folk dance had been around since the 1700s. The song, or something like it, showed up in 1857 in the United States when a couple of sisters from England were visiting New Hampshire and passed along the steps to locals there. You know the steps. “You put your right foot…”

"You put your right foot.." in your ski binding. After that, you might do the Hokey Pokey. This picture was taken in the 1940s at Sun Valley, about the same time everyone was dancing the Hokey Pokey in the lodge. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

"You put your right foot.." in your ski binding. After that, you might do the Hokey Pokey. This picture was taken in the 1940s at Sun Valley, about the same time everyone was dancing the Hokey Pokey in the lodge. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on September 02, 2019 04:00

September 1, 2019

Massacre Rocks Indian

Traveling the Oregon Trail wasn’t always a one-way trip. Several of those who made the trek came back along the trail years later to reminisce.

Ezra Meeker is probably the best-known Oregon Trail traveler to retrace his journey. He did it several times in order to memorialize the trail’s importance in U.S. history. In his late 70s, 1906-1908, and again from 1910-1912, he travelled the route in a covered wagon and encouraged communities along the way to install memorials to mark the trail. The trail was being obliterated by the passage of time. Without his efforts, we would know much less about that history than we do today. I’ll do an extended post about Meeker in the future.

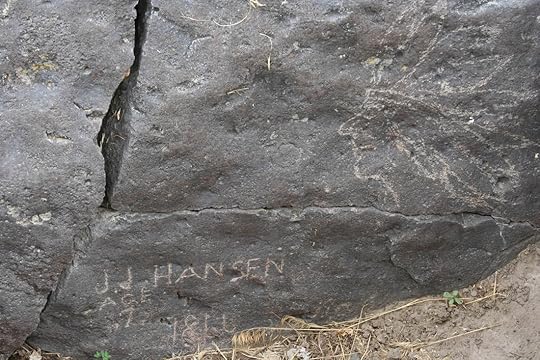

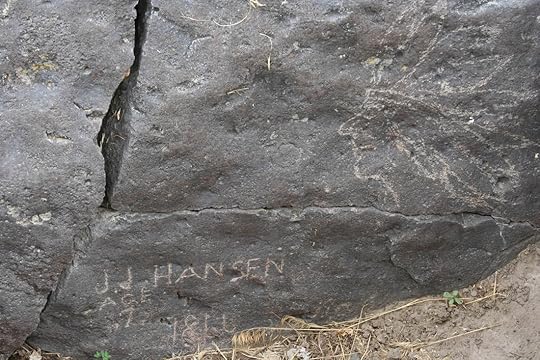

Today, I want to tell a smaller story that relates only to Idaho, specifically to a single rock. The photo shows the image of an Indian chief scratched onto the surface of a lava rock. It’s a good rendition when you consider that the artist was seven years old. J.J. Hansen was in a wagon train on the Oregon Trail with his parents on their way to Portland, Oregon in 1866 when they stopped at Register Rock. Many travelers carved their names or initials on the big rock, which is a feature of Massacre Rocks State Park today. Young Mr. Hansen found a smaller rock to call his own and proceeded to chip out the image of an Indian and what looks like a cowboy across the rock facing the chief. Hansen called the man in the hat a preacher. He added the year to his artwork, 1866.

Hansen visited the site again in 1908, 42 years later. His youthful artistic leanings had blossomed as an adult and he had become a sculptor. He found the rock on which he had practiced his art and added the new year, 1908, to complete the circle. The latter date is difficult to see in the picture. It is on the lower right.

Ezra Meeker is probably the best-known Oregon Trail traveler to retrace his journey. He did it several times in order to memorialize the trail’s importance in U.S. history. In his late 70s, 1906-1908, and again from 1910-1912, he travelled the route in a covered wagon and encouraged communities along the way to install memorials to mark the trail. The trail was being obliterated by the passage of time. Without his efforts, we would know much less about that history than we do today. I’ll do an extended post about Meeker in the future.

Today, I want to tell a smaller story that relates only to Idaho, specifically to a single rock. The photo shows the image of an Indian chief scratched onto the surface of a lava rock. It’s a good rendition when you consider that the artist was seven years old. J.J. Hansen was in a wagon train on the Oregon Trail with his parents on their way to Portland, Oregon in 1866 when they stopped at Register Rock. Many travelers carved their names or initials on the big rock, which is a feature of Massacre Rocks State Park today. Young Mr. Hansen found a smaller rock to call his own and proceeded to chip out the image of an Indian and what looks like a cowboy across the rock facing the chief. Hansen called the man in the hat a preacher. He added the year to his artwork, 1866.

Hansen visited the site again in 1908, 42 years later. His youthful artistic leanings had blossomed as an adult and he had become a sculptor. He found the rock on which he had practiced his art and added the new year, 1908, to complete the circle. The latter date is difficult to see in the picture. It is on the lower right.

Published on September 01, 2019 04:00

August 31, 2019

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What name does Goddin’s River go by today?

A. The Boise River.

B. The Snake River.

C. The Malad River.

D. The Bear River.

E. The Lost River.

2). What record did John Loveridge hold in 1891?

A. First to bicycle between Mountain Home and Boise.

B. Fastest slalom time in downhill skiing.

C. Quickest body to surface after drowning in the Snake River.

D. Most goals in a Boise polo match.

E. Boise City champion pelota player.

3). What figure in Northwest history is Grace Slick related to?

A. Meriwether Lewis.

B. James Hogan.

C. Henry Lemp.

D. Marcus Whitman.

E. George Shoup.

4). Who first discovered gold in what would become Orofino Creek?

A. Jane Timothy Silcock

B. Elias D. Pierce

C. John Silcott

D. Marcus Whitman.

E. W.F. Bassett

5) How many “Muffler Men” are there in Idaho?

A. Trick question: Three men and one woman.

B. Two.

C. Four.

D. Zero.

E. Only one. Answers

Answers

1, E

2, C

3, D

4, E

5, A

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What name does Goddin’s River go by today?

A. The Boise River.

B. The Snake River.

C. The Malad River.

D. The Bear River.

E. The Lost River.

2). What record did John Loveridge hold in 1891?

A. First to bicycle between Mountain Home and Boise.

B. Fastest slalom time in downhill skiing.

C. Quickest body to surface after drowning in the Snake River.

D. Most goals in a Boise polo match.

E. Boise City champion pelota player.

3). What figure in Northwest history is Grace Slick related to?

A. Meriwether Lewis.

B. James Hogan.

C. Henry Lemp.

D. Marcus Whitman.

E. George Shoup.

4). Who first discovered gold in what would become Orofino Creek?

A. Jane Timothy Silcock

B. Elias D. Pierce

C. John Silcott

D. Marcus Whitman.

E. W.F. Bassett

5) How many “Muffler Men” are there in Idaho?

A. Trick question: Three men and one woman.

B. Two.

C. Four.

D. Zero.

E. Only one.

Answers

Answers1, E

2, C

3, D

4, E

5, A

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on August 31, 2019 04:00

August 30, 2019

John Baptiste Charbonneau

If you picture the dollar coin that features Sacajawea (or Sacagawea, if you prefer) you may remember the eagle on the obverse, and you might remember that Shoshone Tribal member Randy’L Teton served as the model for Sacajawea. But, did you remember that there are two people depicted on the coin?

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was a part of the famous trip Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery made to the Pacific. He would not remember the trip, because he was just a baby on his mother’s back, as depicted on the dollar coin. He played an important role just the same. Seeing a woman with a child as part of that strange group, which included a black man and a giant black dog, helped assure tribes they encountered that this was not a war party.

William Clark took a liking to the boy, giving him the nickname Pomp. More than that, after the death of Sacajawea, Clark took him in and paid for his education.

Jean Baptiste spoke English and French fluently. His father was Toussaint Charbonneau, a French trader who also went along on the expedition. He knew Shoshone well, thanks to his mother, and could converse in several Indian languages. During six years in Europe, he also picked up German and Spanish.

Charbonneau led expeditions in the West and guided for others. In 1846 he was the head guide for the Mormon Battalion’s trek from Kansas to San Diego. He was a trapper, gambler, magistrate, and freighter. He prospected for gold, and once owned a hotel in northern California. He even served as mayor of Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, near San Diego, for a time.

Pomp probably died as the result of an accident at a river crossing in Oregon when he was on his way, perhaps, to the mines in the Owyhees. His destination is uncertain as are the exact details of his death. An obituary for Jean Baptiste appeared in the Owyhee Avalanche in 1866, listing pneumonia as the cause of death.

There is a competing story about a Jean Baptiste Charbonneau who died on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, in 1885. Evidence that this was the Charbonneau that accompanied Lewis and Clark is slim.

The grave of John Baptiste Charbonneau, about 100 miles southwest of Ontario, Oregon is listed on the national register of historic places, and boasts no fewer than three historic markers.

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was a part of the famous trip Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery made to the Pacific. He would not remember the trip, because he was just a baby on his mother’s back, as depicted on the dollar coin. He played an important role just the same. Seeing a woman with a child as part of that strange group, which included a black man and a giant black dog, helped assure tribes they encountered that this was not a war party.

William Clark took a liking to the boy, giving him the nickname Pomp. More than that, after the death of Sacajawea, Clark took him in and paid for his education.

Jean Baptiste spoke English and French fluently. His father was Toussaint Charbonneau, a French trader who also went along on the expedition. He knew Shoshone well, thanks to his mother, and could converse in several Indian languages. During six years in Europe, he also picked up German and Spanish.

Charbonneau led expeditions in the West and guided for others. In 1846 he was the head guide for the Mormon Battalion’s trek from Kansas to San Diego. He was a trapper, gambler, magistrate, and freighter. He prospected for gold, and once owned a hotel in northern California. He even served as mayor of Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, near San Diego, for a time.

Pomp probably died as the result of an accident at a river crossing in Oregon when he was on his way, perhaps, to the mines in the Owyhees. His destination is uncertain as are the exact details of his death. An obituary for Jean Baptiste appeared in the Owyhee Avalanche in 1866, listing pneumonia as the cause of death.

There is a competing story about a Jean Baptiste Charbonneau who died on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, in 1885. Evidence that this was the Charbonneau that accompanied Lewis and Clark is slim.

The grave of John Baptiste Charbonneau, about 100 miles southwest of Ontario, Oregon is listed on the national register of historic places, and boasts no fewer than three historic markers.

Published on August 30, 2019 04:00

August 29, 2019

Do You Have a Jockey Box?

When you hear the term “jockey box” what comes to mind? If you’ve been around Idaho for a while, you probably think of what most people in the US call a glove compartment. If you’re new to the state, you’re likely baffled by the term.

Knowing that it was a mystery to a lot of folks, I did a little research. The first instance of the term I found in an Idaho paper was in the October 18, 1881, edition of the Idaho World. It was mentioned during an interview with convicted murderer Henry McDonald. In describing the murder of George Meyer. McDonald said, “He and I then got into a quarrel about the dog, and he came at me, I pushed him, and he fell over a sagebrush; he got up and started for the jockey box to get a six-shooter…” The jockey box in that instance was probably a box beneath the seat of the man’s wagon or buckboard.

The next mention of the phrase is from the Idaho Daily Statesman, June 23, 1896. A couple of lines tell the story, “He opened the jockey box on his seat and rummaged around in it, finally producing a small hatchet and a big nail.

“‘I guess you’ll have to drive her out with this,’ said he, and he sat down on the ground and hung on to a buckeye bush with both hands, while one of his companions placed the end of the nail against the side of the tooth and hit it with the hatchet.”

Cowboy dentistry.

Note that those early mentions were about wagons, not cars. The term referred to a small (as jockeys are supposed to be) box in which one stored certain essentials, such as guns and dental tools. That small box inside automobiles that served the same purpose picked up the same name in Idaho and other Western states.

So, laugh all you want, but what do you store in YOUR glove box? Gloves? Maybe. More likely the owner’s manual, an old CD, your registration, a couple of pens that don’t work, 16 cents, and a four-year-old peppermint. So, why call it a glove compartment? Jockey box is a nice generic term to indicate that the box is equivalent to the junk drawer in your house. You know, a place to put your hatchet.

Knowing that it was a mystery to a lot of folks, I did a little research. The first instance of the term I found in an Idaho paper was in the October 18, 1881, edition of the Idaho World. It was mentioned during an interview with convicted murderer Henry McDonald. In describing the murder of George Meyer. McDonald said, “He and I then got into a quarrel about the dog, and he came at me, I pushed him, and he fell over a sagebrush; he got up and started for the jockey box to get a six-shooter…” The jockey box in that instance was probably a box beneath the seat of the man’s wagon or buckboard.

The next mention of the phrase is from the Idaho Daily Statesman, June 23, 1896. A couple of lines tell the story, “He opened the jockey box on his seat and rummaged around in it, finally producing a small hatchet and a big nail.

“‘I guess you’ll have to drive her out with this,’ said he, and he sat down on the ground and hung on to a buckeye bush with both hands, while one of his companions placed the end of the nail against the side of the tooth and hit it with the hatchet.”

Cowboy dentistry.

Note that those early mentions were about wagons, not cars. The term referred to a small (as jockeys are supposed to be) box in which one stored certain essentials, such as guns and dental tools. That small box inside automobiles that served the same purpose picked up the same name in Idaho and other Western states.

So, laugh all you want, but what do you store in YOUR glove box? Gloves? Maybe. More likely the owner’s manual, an old CD, your registration, a couple of pens that don’t work, 16 cents, and a four-year-old peppermint. So, why call it a glove compartment? Jockey box is a nice generic term to indicate that the box is equivalent to the junk drawer in your house. You know, a place to put your hatchet.

Published on August 29, 2019 04:00