Rick Just's Blog, page 189

August 18, 2019

Dispatches from the Past

Time for one of our occasional Dispatches from the Past where we feature oddities from newspapers that caught our eye while researching some unrelated topic.

From the August 8. 1867, Owyhee Bullion, an ad for the Poorman Saloon in Ruby City. “I have now opened a saloon in my own elegant styled building. I desire the patronage of those only WHO ARE LIABEL TO PAY.”

For context on this next one, you need to know that Idaho was a prohibition state beginning in 1916. Here’s a little blurb from the September 18, 1917 American Falls Press.

“Earl Fleming of the Bonanza Bar country was in town Friday night and somewhere in his travels picked up a bottle of the forbidden. He was in one of the pool halls and Deputy Sheriff Fred Walworth came in. Now you know Earl had known Fred a long time so he proffered the latter the bottle. Fred took the bottle all right, also the prisoner and Earl, after waiving his preliminary hearing, is awaiting under bond the session of the district court. Moral: don’t offer a sheriff a drink in a crowded pool hall.”

From the Blackfoot Idaho Republican, November 10, 1920.

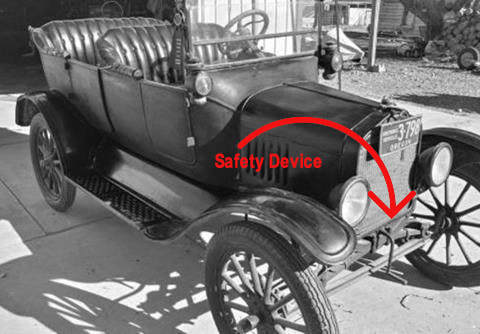

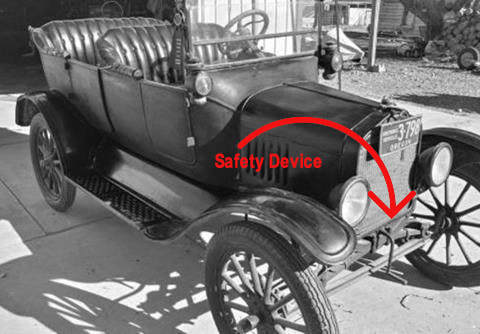

“Because he had the Ford habit of getting out of his car when he wanted to start the engine, J.T. Burroughs, traveling salesman for an Idaho Falls wholesale grocery company, lost his Dodge car Saturday night, when it was struck at the crossing north of the depot by Short Line train No. 34, and barely escaped himself.”

The article went on to explain that the Dodge had stalled on the tracks, so Burroughs, out of habit, jumped out to crank the thing to a start. That’s when the train hit the car, which featured one of those new-fangled dashboard starters.

From the August 8. 1867, Owyhee Bullion, an ad for the Poorman Saloon in Ruby City. “I have now opened a saloon in my own elegant styled building. I desire the patronage of those only WHO ARE LIABEL TO PAY.”

For context on this next one, you need to know that Idaho was a prohibition state beginning in 1916. Here’s a little blurb from the September 18, 1917 American Falls Press.

“Earl Fleming of the Bonanza Bar country was in town Friday night and somewhere in his travels picked up a bottle of the forbidden. He was in one of the pool halls and Deputy Sheriff Fred Walworth came in. Now you know Earl had known Fred a long time so he proffered the latter the bottle. Fred took the bottle all right, also the prisoner and Earl, after waiving his preliminary hearing, is awaiting under bond the session of the district court. Moral: don’t offer a sheriff a drink in a crowded pool hall.”

From the Blackfoot Idaho Republican, November 10, 1920.

“Because he had the Ford habit of getting out of his car when he wanted to start the engine, J.T. Burroughs, traveling salesman for an Idaho Falls wholesale grocery company, lost his Dodge car Saturday night, when it was struck at the crossing north of the depot by Short Line train No. 34, and barely escaped himself.”

The article went on to explain that the Dodge had stalled on the tracks, so Burroughs, out of habit, jumped out to crank the thing to a start. That’s when the train hit the car, which featured one of those new-fangled dashboard starters.

Published on August 18, 2019 04:00

August 17, 2019

Bear River Superlative

People seem to love superlatives. You know, the first, the biggest, the best. Bear River holds a few distinctions like that.

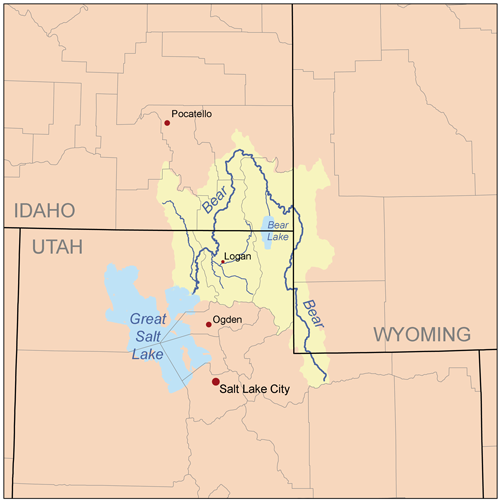

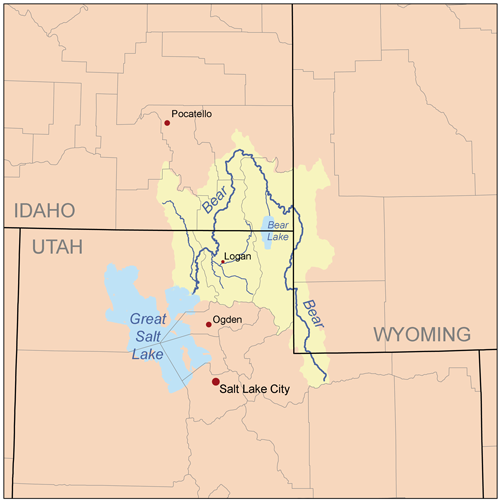

First, though it is probably not unique in this sense, the Bear River flows through three states, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho. It starts in Utah, winds into Wyoming, drifts back into Utah, then into Wyoming again, before entering Idaho. The longest stretch of the river is in Idaho, looping up past Montpelier to Soda Springs, then plunging down and back into Utah, where it flows into the Great Salt Lake.

That’s where its one, true superlative comes from. The Bear River is the largest river in the United States whose waters never reach an ocean. The outflow of the river is less than 100 miles from where it began, but the water journeys some 350 miles to get there.

It wasn’t always so. The Bear River once—geologically once—flowed into the Snake River like most other respectable streams in southern Idaho. Lava flows that occurred long before you were born—maybe before anyone was born—diverted the flow south from Soda Springs.

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

First, though it is probably not unique in this sense, the Bear River flows through three states, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho. It starts in Utah, winds into Wyoming, drifts back into Utah, then into Wyoming again, before entering Idaho. The longest stretch of the river is in Idaho, looping up past Montpelier to Soda Springs, then plunging down and back into Utah, where it flows into the Great Salt Lake.

That’s where its one, true superlative comes from. The Bear River is the largest river in the United States whose waters never reach an ocean. The outflow of the river is less than 100 miles from where it began, but the water journeys some 350 miles to get there.

It wasn’t always so. The Bear River once—geologically once—flowed into the Snake River like most other respectable streams in southern Idaho. Lava flows that occurred long before you were born—maybe before anyone was born—diverted the flow south from Soda Springs.

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

Kmusser [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)]

Published on August 17, 2019 04:00

August 16, 2019

Basque Radio

The Basque Museum in Boise tells the fascinating story of the culture and history of a people who have long been an important part of the fabric of our lives in Idaho. There you’ll learn about the role language has played in that history, both in the way it sometimes separated Basques from others in the West and the way it kept the traditions of the community alive.

In 1949 some Basques in Boise thought of a way to send out words and music that would be familiar to sheepherders and other Basques across the spread of the West. They started a weekly radio program on KDSH (later KBOI) broadcast entirely in the Basque language (Euskra). The program featured news of loved ones, such as birthdays, weddings, and births, as well as news of the world, weather, and the latest music from Spain.

The show also aired on KGEM at one time. The photo is of Espe Alegria, the “Voice of the Basques” on KGEM in about 1954. With volunteer announcers, the Basque language program aired for 30 years.

In 1949 some Basques in Boise thought of a way to send out words and music that would be familiar to sheepherders and other Basques across the spread of the West. They started a weekly radio program on KDSH (later KBOI) broadcast entirely in the Basque language (Euskra). The program featured news of loved ones, such as birthdays, weddings, and births, as well as news of the world, weather, and the latest music from Spain.

The show also aired on KGEM at one time. The photo is of Espe Alegria, the “Voice of the Basques” on KGEM in about 1954. With volunteer announcers, the Basque language program aired for 30 years.

Published on August 16, 2019 04:00

August 15, 2019

The Muffler Men of Idaho

You’d think a 25-foot-tall man born in 1967 would have enough documentation behind him to have his story told accurately, wouldn’t you?

Not so with the lumberjack that stands at 1405 Main Avenue in St. Maries. You’ll see stories about him that say he’s standing in front of the High School, where the sports teams are called the Lumberjacks. Well, the high school isn’t far away, but he’s really on the lawn of an elementary school. And, is he standing? He’s not sitting, but he also doesn’t have feet, so…

Often, you’ll see the lumberjack referred to as Paul Bunyan. He’s really a generic lumberjack. He’s also a Muffler Man.

What? It turns out that giant Fiberglass men are referred to in general as “Muffler Men.” The St. Maries man is holding an axe, but many of the early giants held mufflers in their hands to advertise automotive service shops. The vast majority of them were made in California by International Fiberglass, a boat builder, beginning in 1962. The first “Muffler Man” was actually a lumberjack. Specifically, it was a Paul Bunyan statue used to advertise a restaurant in Arizona on Route 66.

Thousands of them were made over the years from the same mold, but with some variations. They were cheap—$1,000 to $3,000—and they caught your attention. They held all kinds of jobs, promoting gas stations, restaurants, and roadside attractions. They were dressed as Vikings, football players, astronauts, pirates, soldiers, chefs, and cowboys. There’s a cowboy along the interstate near Wendell holding a stop sign in his hands, hoping you’ll stop by an RV dealership.

The third known Muffler Man in Idaho has a cushy job. He doesn’t even have to stand outside in the weather. Big Don, as he’s known, towers inside Pocatello’s Museum of Clean, where he wields a giant mop. Needless to say, he’s spotless. Word is that he has a cowboy hat, too, but he doesn’t wear it indoors.

But back to that lumberjack. Although he’s generically a Muffler Man, he’s specifically a Texaco “Big Friendly.” There were originally some 500 of them, but only a half dozen exist today. He’s a little taller than the average Muffler Man, although there’s the issue of the feet. There’s a story that says he arrived with his feet on backwards so those were chopped off and he was mounted in concrete. There’s also a rumor that the lumberjack fell off a truck or was found in the woods.

Wherever the St. Maries lumberjack came from, he’s not the only one of his kind in Idaho. His brothers in Wendell and Pocatello also have at least one sister in the state, a Jackie Kennedy Onassis lookalike in Blackfoot. Her name is Martha and she advertises Martha’s Café. She was “born” a Uniroyal Gal. There are maybe a dozen of them left around the country. Martha is conservatively dressed, but she originally hit the streets wearing a bikini.

Alert readers who are certain there’s another Muffler Man or woman in the state are requested to send photographic evidence of same. Maybe we’ll put together a reunion. The mascot in St. Maries is a lumberjack. He's also a "Muffler Man."

The mascot in St. Maries is a lumberjack. He's also a "Muffler Man."  Big Don is ready to mop up any spills in Pocatello. It's a cushy job for Muffler Man.

Big Don is ready to mop up any spills in Pocatello. It's a cushy job for Muffler Man.  The stop sign gives you a clue about the size of this guy near Wendell.

The stop sign gives you a clue about the size of this guy near Wendell.

Not so with the lumberjack that stands at 1405 Main Avenue in St. Maries. You’ll see stories about him that say he’s standing in front of the High School, where the sports teams are called the Lumberjacks. Well, the high school isn’t far away, but he’s really on the lawn of an elementary school. And, is he standing? He’s not sitting, but he also doesn’t have feet, so…

Often, you’ll see the lumberjack referred to as Paul Bunyan. He’s really a generic lumberjack. He’s also a Muffler Man.

What? It turns out that giant Fiberglass men are referred to in general as “Muffler Men.” The St. Maries man is holding an axe, but many of the early giants held mufflers in their hands to advertise automotive service shops. The vast majority of them were made in California by International Fiberglass, a boat builder, beginning in 1962. The first “Muffler Man” was actually a lumberjack. Specifically, it was a Paul Bunyan statue used to advertise a restaurant in Arizona on Route 66.

Thousands of them were made over the years from the same mold, but with some variations. They were cheap—$1,000 to $3,000—and they caught your attention. They held all kinds of jobs, promoting gas stations, restaurants, and roadside attractions. They were dressed as Vikings, football players, astronauts, pirates, soldiers, chefs, and cowboys. There’s a cowboy along the interstate near Wendell holding a stop sign in his hands, hoping you’ll stop by an RV dealership.

The third known Muffler Man in Idaho has a cushy job. He doesn’t even have to stand outside in the weather. Big Don, as he’s known, towers inside Pocatello’s Museum of Clean, where he wields a giant mop. Needless to say, he’s spotless. Word is that he has a cowboy hat, too, but he doesn’t wear it indoors.

But back to that lumberjack. Although he’s generically a Muffler Man, he’s specifically a Texaco “Big Friendly.” There were originally some 500 of them, but only a half dozen exist today. He’s a little taller than the average Muffler Man, although there’s the issue of the feet. There’s a story that says he arrived with his feet on backwards so those were chopped off and he was mounted in concrete. There’s also a rumor that the lumberjack fell off a truck or was found in the woods.

Wherever the St. Maries lumberjack came from, he’s not the only one of his kind in Idaho. His brothers in Wendell and Pocatello also have at least one sister in the state, a Jackie Kennedy Onassis lookalike in Blackfoot. Her name is Martha and she advertises Martha’s Café. She was “born” a Uniroyal Gal. There are maybe a dozen of them left around the country. Martha is conservatively dressed, but she originally hit the streets wearing a bikini.

Alert readers who are certain there’s another Muffler Man or woman in the state are requested to send photographic evidence of same. Maybe we’ll put together a reunion.

The mascot in St. Maries is a lumberjack. He's also a "Muffler Man."

The mascot in St. Maries is a lumberjack. He's also a "Muffler Man."  Big Don is ready to mop up any spills in Pocatello. It's a cushy job for Muffler Man.

Big Don is ready to mop up any spills in Pocatello. It's a cushy job for Muffler Man.  The stop sign gives you a clue about the size of this guy near Wendell.

The stop sign gives you a clue about the size of this guy near Wendell.

Published on August 15, 2019 04:00

August 14, 2019

Art Deco Courthouses

Government buildings are often unimaginative cubes designed with little thought of beauty. Yet, much of Idaho’s most interesting architecture can be found in government buildings. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was responsible for funding seven county courthouses in Idaho, all with in the Art Deco style. Art Deco came into vogue in the US and Europe in the 1920s. The style found its way into architecture, as well as furniture, jewelry, cars, fashion and everyday objects such as radios. It was a modern style that often infused functional objects from buildings to vacuum cleaners with artistic touches.

The following were all built using WPA funding. All are Art Deco, and all are also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Boundary County Courthouse in Bonners Ferry was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941. National Register of Historic Places.

The brick Cassia County Courthouse in Burley was built in 1939.

The Franklin County Courthouse in Preston was built in 1939. Hyrum Pope, of Salt Lake City, was the architect. Pope died of a heart attack while on site inspecting construction of the building.

The Gem County Courthouse in Emmett was designed by Frank Hummel of the Boise firm Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1938.

The Jefferson County Courthouse in Rigby was built in 1938. Idaho Falls architects Sundberg and Sundberg designed it.

The Jerome County Courthouse, in Jerome was built in 1939.

The Oneida County Courthouse in Malad was built in 1938 from plans drawn up by Sundberg and Sundberg.

The Washington County Courthouse in Weiser, was designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1939.

The following were all built using WPA funding. All are Art Deco, and all are also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Boundary County Courthouse in Bonners Ferry was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941. National Register of Historic Places.

The brick Cassia County Courthouse in Burley was built in 1939.

The Franklin County Courthouse in Preston was built in 1939. Hyrum Pope, of Salt Lake City, was the architect. Pope died of a heart attack while on site inspecting construction of the building.

The Gem County Courthouse in Emmett was designed by Frank Hummel of the Boise firm Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1938.

The Jefferson County Courthouse in Rigby was built in 1938. Idaho Falls architects Sundberg and Sundberg designed it.

The Jerome County Courthouse, in Jerome was built in 1939.

The Oneida County Courthouse in Malad was built in 1938 from plans drawn up by Sundberg and Sundberg.

The Washington County Courthouse in Weiser, was designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1939.

Published on August 14, 2019 04:00

August 13, 2019

Malad River, Malad River

Idaho has two Malad Rivers, both named such because of encounter early trappers had with bad beavers. No, not juvenile delinquent beavers, or beavers gone rogue because of bad upbringing or the crowd they ran with. These were beavers that were eaten and got their revenge by passing on some malady to the person who feasted on their flesh.

Alexander Ross had the honor of naming Idaho’s Malad River that empties into the Bear River. He called it “River Aux Malades.” He recorded the experience in his journal in the fall of 1824. After breakfast that day many of his men were taken ill—so many that Ross was quite certain it was something they ate. He did a survey of the ailing and the fit and found that those who had partaken of fresh beaver that morning were the former.

Thirty-seven men in his party “were seized with grippings and laid up. The sickness first showed itself in a pain about the kidneys, then the stomach, and afterwards the back of the neck and all the nerves, and by and by the whole system became affected. The sufferers were almost speechless and motionless, having scarcely the power to stir yet suffering great pain, which caused froth about the mouth.”

It's at this point that Ross described the medicine they had on hand in their camp: none. So, of course a leader improvises. “The first thing I applied was gunpowder. Drawing therefore a handful or two of it into a dish of warm water and mixing it up I made them drink strong doses of it.”

The gunpowder smoothie had no positive effect, shockingly. Next he boiled up a kettle of fat and spiced it up with pepper for the ailing to drink. Ross reported that did the trick. Everyone started getting better. A skeptic might think the ailment had simply run its course or the men began to feign improvement for fear of whatever Ross might concoct to pour down their throats next.

The theory Ross came up with was that the beaver, which had little bark in the area to feast on, had ingested some poisonous roots. An Indian they happened upon made them to understand that you could roast the local beaver meat, but if you boiled it, you’d get sick every time.

So, note that in your recipe book. When eating Oneida County beaver, roast, don’t boil. You’re welcome.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Alexander Ross had the honor of naming Idaho’s Malad River that empties into the Bear River. He called it “River Aux Malades.” He recorded the experience in his journal in the fall of 1824. After breakfast that day many of his men were taken ill—so many that Ross was quite certain it was something they ate. He did a survey of the ailing and the fit and found that those who had partaken of fresh beaver that morning were the former.

Thirty-seven men in his party “were seized with grippings and laid up. The sickness first showed itself in a pain about the kidneys, then the stomach, and afterwards the back of the neck and all the nerves, and by and by the whole system became affected. The sufferers were almost speechless and motionless, having scarcely the power to stir yet suffering great pain, which caused froth about the mouth.”

It's at this point that Ross described the medicine they had on hand in their camp: none. So, of course a leader improvises. “The first thing I applied was gunpowder. Drawing therefore a handful or two of it into a dish of warm water and mixing it up I made them drink strong doses of it.”

The gunpowder smoothie had no positive effect, shockingly. Next he boiled up a kettle of fat and spiced it up with pepper for the ailing to drink. Ross reported that did the trick. Everyone started getting better. A skeptic might think the ailment had simply run its course or the men began to feign improvement for fear of whatever Ross might concoct to pour down their throats next.

The theory Ross came up with was that the beaver, which had little bark in the area to feast on, had ingested some poisonous roots. An Indian they happened upon made them to understand that you could roast the local beaver meat, but if you boiled it, you’d get sick every time.

So, note that in your recipe book. When eating Oneida County beaver, roast, don’t boil. You’re welcome.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Yummy beaver tails. Note that this depiction is of a Canadian pastry, not to be confused with the delicacy you might be tempted to try from either of Idaho’s Malad rivers.

Published on August 13, 2019 04:00

August 12, 2019

American Falls

In a previous Speaking of Idaho Post about moving the town of American Falls to make way for the rising reservoir behind what would be the American Falls Dam, I had a couple of folks ask if I knew of any pictures of the falls before the dam.

I had wondered what the falls had looked like. Were they spectacular, something akin to Shoshone Falls? No, more akin to Idaho Falls, a drop in the river elevation but not a heart-stopping one.

The photo shows the first power plant located on the falls. It was built in 1902, and acquired by Idaho Power in 1916. An Oregon Shortline train is shown in the background chugging across the the railroad bridge. They started building the first dam in 1925 and completed it in 1927. It’s not the dam you can drive across today, though. That was completed in 1978, downstream from the original. That followed a scare in 1976 when the Teton Dam failed. Water managers were afraid the sudden influx from that failure might cause the American Falls Dam to fail, too, sending even more water crashing down the Snake, taking out dams as it went, increasing in volume all the way to the Columbia. To prevent that, they threw open the gates at American Falls, avoiding the potential of an even larger disaster.

Power generation at American Falls is the reason for the name Power County. The current dam churns out 112 megawatts annually.

I had wondered what the falls had looked like. Were they spectacular, something akin to Shoshone Falls? No, more akin to Idaho Falls, a drop in the river elevation but not a heart-stopping one.

The photo shows the first power plant located on the falls. It was built in 1902, and acquired by Idaho Power in 1916. An Oregon Shortline train is shown in the background chugging across the the railroad bridge. They started building the first dam in 1925 and completed it in 1927. It’s not the dam you can drive across today, though. That was completed in 1978, downstream from the original. That followed a scare in 1976 when the Teton Dam failed. Water managers were afraid the sudden influx from that failure might cause the American Falls Dam to fail, too, sending even more water crashing down the Snake, taking out dams as it went, increasing in volume all the way to the Columbia. To prevent that, they threw open the gates at American Falls, avoiding the potential of an even larger disaster.

Power generation at American Falls is the reason for the name Power County. The current dam churns out 112 megawatts annually.

Published on August 12, 2019 04:00

August 11, 2019

Starship Tenuous Connection

Okay, rock and rollers, we’re going on a little journey today, so buckle in. This will take at least an airplane to get from where we’re starting to where we’re going. Maybe a starship.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman along with Henry Harmon Spalding were Presbyterian missionaries who were the first people to roll into what is now Idaho. Literally, they had the first set of wheels to enter the country. Four wheels were on a wagon that got them almost to Fort Hall in 1836 before they decided that a cart would work better to cross the desert land. So, they took two wheels off and converted the wagon to a cart.

Books have been written about both sets of missionaries, so we’re going to do just a touch and go with our airplane-cum-starship, saying only that the Spaldings set up the first mission in what would become Idaho at Lapwai, not far from what would become Lewiston. The Whitman’s mission was near Walla Walla. They were murdered by Indians, and, we don’t have time to tell that whole story, so off we go into the air.

From our perch in the metaphorical sky we spot Perrin Beza Whitman, the adopted son, and nephew, of Marcus and Narcissa. He survived the massacre because he was in the Dalles on an errand when it happened. Zooming over the years Perrin Whitman is seen moving to Lapwai in 1863 to work as an interpreter in the Indian schools. In 1883 he and his family moved to Lewiston, where he became a trusted businessman for his remaining years, passing away in 1899.

Here’s where we swoop to pick up the trail of Perrin Whitman’s daughter, Elizabeth Auzella “Lizzie” Whitman, born in 1856. We’re picking up speed, so skipping to 1875 we find Lizzie marrying Harry K. Barnett, a title company executive in Lewiston. Lizzie was a singer, entertaining the community with her voice, and playing guitar and violin as well. No time for a standing ovation, though, because we’re back in the air and following Lizzie’s son, Marcus—no doubt named after the murdered Marcus.

Marcus Barton had a wife, but we’re going too fast to mention her—nearing light speed now. Marcus had a daughter who was named Virginia. Virginia—buckle in tight—met a man named Wilford Wing at the University of Washington where both were students. They married and had some kids, one of whom was named Grace Barnett Wing, born in 1939. The family ended up in Palo Alto, where Grace went to high school before building the nearby city of San Francisco out of rock and roll.

And that’s the Marcus and Narcissa Whitman—and Idaho—connection to Grace Slick, one of rock and roll’s greats and the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane-cum-Jefferson Starship.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman along with Henry Harmon Spalding were Presbyterian missionaries who were the first people to roll into what is now Idaho. Literally, they had the first set of wheels to enter the country. Four wheels were on a wagon that got them almost to Fort Hall in 1836 before they decided that a cart would work better to cross the desert land. So, they took two wheels off and converted the wagon to a cart.

Books have been written about both sets of missionaries, so we’re going to do just a touch and go with our airplane-cum-starship, saying only that the Spaldings set up the first mission in what would become Idaho at Lapwai, not far from what would become Lewiston. The Whitman’s mission was near Walla Walla. They were murdered by Indians, and, we don’t have time to tell that whole story, so off we go into the air.

From our perch in the metaphorical sky we spot Perrin Beza Whitman, the adopted son, and nephew, of Marcus and Narcissa. He survived the massacre because he was in the Dalles on an errand when it happened. Zooming over the years Perrin Whitman is seen moving to Lapwai in 1863 to work as an interpreter in the Indian schools. In 1883 he and his family moved to Lewiston, where he became a trusted businessman for his remaining years, passing away in 1899.

Here’s where we swoop to pick up the trail of Perrin Whitman’s daughter, Elizabeth Auzella “Lizzie” Whitman, born in 1856. We’re picking up speed, so skipping to 1875 we find Lizzie marrying Harry K. Barnett, a title company executive in Lewiston. Lizzie was a singer, entertaining the community with her voice, and playing guitar and violin as well. No time for a standing ovation, though, because we’re back in the air and following Lizzie’s son, Marcus—no doubt named after the murdered Marcus.

Marcus Barton had a wife, but we’re going too fast to mention her—nearing light speed now. Marcus had a daughter who was named Virginia. Virginia—buckle in tight—met a man named Wilford Wing at the University of Washington where both were students. They married and had some kids, one of whom was named Grace Barnett Wing, born in 1939. The family ended up in Palo Alto, where Grace went to high school before building the nearby city of San Francisco out of rock and roll.

And that’s the Marcus and Narcissa Whitman—and Idaho—connection to Grace Slick, one of rock and roll’s greats and the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane-cum-Jefferson Starship.

Published on August 11, 2019 04:00

August 10, 2019

The Almo Massacre

So, here’s the story, as commemorated on an Idaho-shaped marker in the tiny Idaho town of Almo. “Dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives in a horrible Indian Massacre, 1861. Three hundred immigrants west bound. Only five escaped. –Erected by S & D of Idaho Pioneers, 1938.”

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back, by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back, by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

Published on August 10, 2019 04:00

August 9, 2019

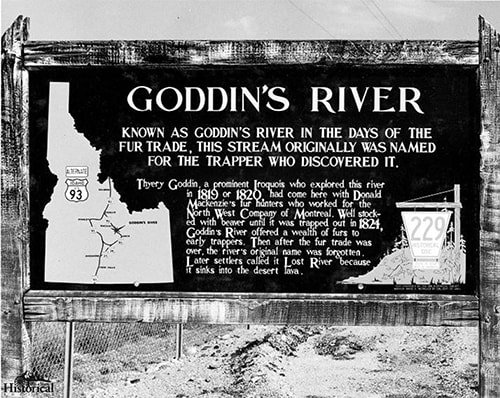

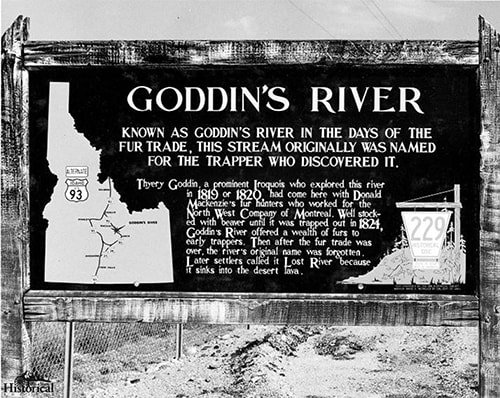

Goddin's River

Now, here’s an interesting theory. You’ve probably heard that Idaho’s Lost Rivers (Big and Little) are so named because they disappear into the desert lava, the water eventually finding its way into the vast Snake River Aquifer. That makes sense, and I’m not disputing it, but I ran across a somewhat alternate theory while researching the original name of Lost River.

Antoine Godin (also referred to in some sources as Thyery Goddin), was an Iroquois who was in what would become Idaho with Donald Mackenzie’s fur hunters. They were looking for whatever might grow fur, particularly beaver, for the North West Company out of Montreal. Godin, or Goddin, found what we today call Lost River. He was impressed enough with the area that he gave the valley and river his name, i.e., Godin River and Godin Valley.

According to Lalia Boone’s well-researched book Idaho Place Names, a Geographical Dictionary, when Godin later returned to the area, he couldn’t find the river, thus the name Lost River became popular. Of course, either explanation could be describing the same phenomena.

Thanks to Godin’s discovery, the river was trapped out of beaver by 1824.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Antoine Godin (also referred to in some sources as Thyery Goddin), was an Iroquois who was in what would become Idaho with Donald Mackenzie’s fur hunters. They were looking for whatever might grow fur, particularly beaver, for the North West Company out of Montreal. Godin, or Goddin, found what we today call Lost River. He was impressed enough with the area that he gave the valley and river his name, i.e., Godin River and Godin Valley.

According to Lalia Boone’s well-researched book Idaho Place Names, a Geographical Dictionary, when Godin later returned to the area, he couldn’t find the river, thus the name Lost River became popular. Of course, either explanation could be describing the same phenomena.

Thanks to Godin’s discovery, the river was trapped out of beaver by 1824.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A 1956 photo of the Idaho Historical Marker telling the story of Goddin (or Godin) River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on August 09, 2019 04:00