Rick Just's Blog, page 185

September 27, 2019

There were Floods, then there were Floods

There is some good-natured competition between north and south in our big state. Who has the best state parks? The best hunting and best fishing? The craziest politicians?

Bragging rights for one thing are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

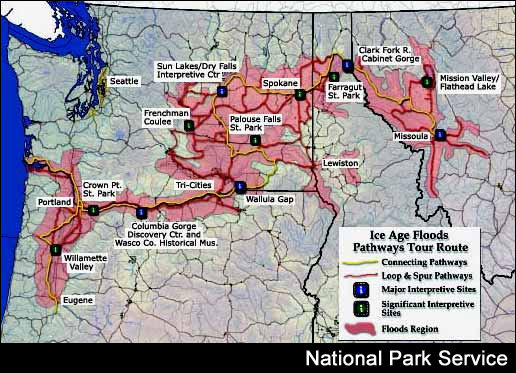

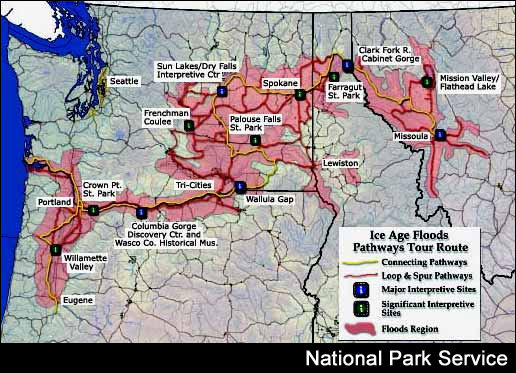

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave

way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons, and ripped the top soil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

Stay dry.

Bragging rights for one thing are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave

way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons, and ripped the top soil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

Stay dry.

Published on September 27, 2019 04:00

September 26, 2019

Potato Wars

December 7, 1937. It was a day that would go down in obscurity. Obscurity is practically my middle name, so let’s take a closer look at the news of that day.

The big story on the front page of the Idaho Statesman was that Douglas Van Vlack, convicted of a triple homicide in Twin Falls, was likely to hang for it. In world news Japan was marching on Nanking and police in Kansas City were using tear gas on strikers at the Ford plant.

But those page one stories didn’t bring us here today. It was a page two story that caught my attention. Datelined Washington, the headline read “Maine Accepts Idaho’s Challenge To Showdown Spud Eating Contest.” Idaho’s congressional delegation had challenged the one from Maine to a contest to take place the next day in the House restaurant.

Representative Owen Brewster (R), Maine, demanded a “blindfold test,” saying that “a Maine potato would be humiliated if its eyes saw an Idaho potato in the same oven.” Nasty politics, it seems, are not a recent invention.

Idaho’s potatoes would be served on Tuesday and Maine’s spuds would be on the Wednesday menu. The judges for the contest were to be delegates from Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Alaska. Those were all territories at that time, so their delegates were probably eager to volunteer for any duty.

The gravity of the decision was not lost on the judges. Would it impact their chances for statehood? Who would want to take a chance?

When it came time to show their cards, each of them was blank. The judges had punted. This gave the press an opportunity to call the decision “half-baked.” The speaker of the House, who was from Alabama, took the opportunity to complain that “This was an Irish potato contest. If it were one to decide the potency of the sweet potato the vote would go unanimously for Alabama yams.”

As the Statesman reported, both camps issued bristling post-potato statements. “’It was a raw decision,’ snarled Maine’s Representative Brewster. ‘Anybody ought to be able to tell those potatoes from Aroostook were best.’”

“’Idaho’s are the best in the world,’ barked Idaho’s Representative D. Worth Clark, ‘those judges must have paralyzed palates.’”

After the advertising stunt, the representatives all enjoyed baked potatoes. Idaho got a bill for $52 worth of butter that had to be purchased locally after the Idaho butter that was being flown in failed to arrive. A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The big story on the front page of the Idaho Statesman was that Douglas Van Vlack, convicted of a triple homicide in Twin Falls, was likely to hang for it. In world news Japan was marching on Nanking and police in Kansas City were using tear gas on strikers at the Ford plant.

But those page one stories didn’t bring us here today. It was a page two story that caught my attention. Datelined Washington, the headline read “Maine Accepts Idaho’s Challenge To Showdown Spud Eating Contest.” Idaho’s congressional delegation had challenged the one from Maine to a contest to take place the next day in the House restaurant.

Representative Owen Brewster (R), Maine, demanded a “blindfold test,” saying that “a Maine potato would be humiliated if its eyes saw an Idaho potato in the same oven.” Nasty politics, it seems, are not a recent invention.

Idaho’s potatoes would be served on Tuesday and Maine’s spuds would be on the Wednesday menu. The judges for the contest were to be delegates from Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Alaska. Those were all territories at that time, so their delegates were probably eager to volunteer for any duty.

The gravity of the decision was not lost on the judges. Would it impact their chances for statehood? Who would want to take a chance?

When it came time to show their cards, each of them was blank. The judges had punted. This gave the press an opportunity to call the decision “half-baked.” The speaker of the House, who was from Alabama, took the opportunity to complain that “This was an Irish potato contest. If it were one to decide the potency of the sweet potato the vote would go unanimously for Alabama yams.”

As the Statesman reported, both camps issued bristling post-potato statements. “’It was a raw decision,’ snarled Maine’s Representative Brewster. ‘Anybody ought to be able to tell those potatoes from Aroostook were best.’”

“’Idaho’s are the best in the world,’ barked Idaho’s Representative D. Worth Clark, ‘those judges must have paralyzed palates.’”

After the advertising stunt, the representatives all enjoyed baked potatoes. Idaho got a bill for $52 worth of butter that had to be purchased locally after the Idaho butter that was being flown in failed to arrive.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A box of Idaho's choicest potatoes were presented to Vice President John N. Garnger (center) by Senators William E. Borah, (left) and James P. Pope in December, 1937. The presentation kicked off the potato “contest” in the House restaurant. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Published on September 26, 2019 04:00

September 25, 2019

Teenagers

Parents, of course you love your children. But be honest, haven’t you once or twice wished there was no such thing as a teenager? There was a time in Idaho history, and world history for that matter, when they did not exist.

The term teenager didn’t start making its way into popular usage until the 1930s and 1940s. The first instance of the word that I found in an Idaho paper was in the Statesman in 1941. It didn’t come up again there until 1943.

Teenage came along a little earlier, though newspapers were slow to standardize it. They used teen age, ‘teen age, “teen” age, and teen-age, depending on the whim of typesetters, perhaps. An expert on the teen-age from Chicago was speaking at a Boise church convention on “the boy problem” in 1914. Thank goodness we’ve now solved that one.

This wasn’t just about semantics. In a sense, there were no teenagers through most of recorded history. There were children who toddled around until they were five or six or seven, not contributing much to a family. Once they could start working at some menial labor, that’s what they did, simply becoming more useful as they got older.

The introduction of standardized education and child labor laws began to change this in the 19th century. Some scholars attribute the invention of the teenager, more-or-less as we know them today, to the automobile. Cars provided freedom for young people to occasionally get away from their parents. Dating became much more common. Then consolidated high schools began to use buses to bring students from further and further away. There they were, together, learning, dating, beginning to dress in their own fashions in the 1950s (picture). Voila! Teenagers!

I have done no research on the subject, but feel confident that eye rolling and insolence came into vogue about the same time as teenager.

The term teenager didn’t start making its way into popular usage until the 1930s and 1940s. The first instance of the word that I found in an Idaho paper was in the Statesman in 1941. It didn’t come up again there until 1943.

Teenage came along a little earlier, though newspapers were slow to standardize it. They used teen age, ‘teen age, “teen” age, and teen-age, depending on the whim of typesetters, perhaps. An expert on the teen-age from Chicago was speaking at a Boise church convention on “the boy problem” in 1914. Thank goodness we’ve now solved that one.

This wasn’t just about semantics. In a sense, there were no teenagers through most of recorded history. There were children who toddled around until they were five or six or seven, not contributing much to a family. Once they could start working at some menial labor, that’s what they did, simply becoming more useful as they got older.

The introduction of standardized education and child labor laws began to change this in the 19th century. Some scholars attribute the invention of the teenager, more-or-less as we know them today, to the automobile. Cars provided freedom for young people to occasionally get away from their parents. Dating became much more common. Then consolidated high schools began to use buses to bring students from further and further away. There they were, together, learning, dating, beginning to dress in their own fashions in the 1950s (picture). Voila! Teenagers!

I have done no research on the subject, but feel confident that eye rolling and insolence came into vogue about the same time as teenager.

Published on September 25, 2019 04:00

September 24, 2019

Seeing Double

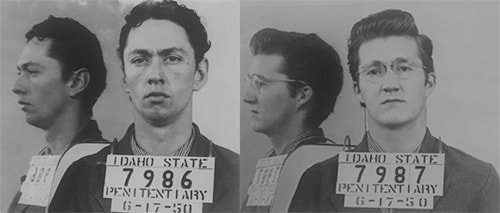

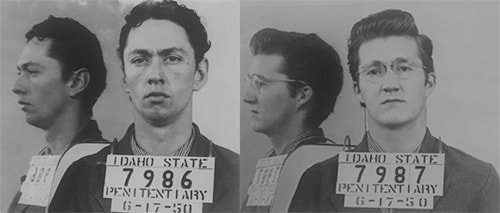

Friday the 13th is thought by some to be an unlucky day. That was certainly the case for Ernie Walrath. 21, and Troy Powell, 20, when Friday, April 13 1951 rolled around. That was the day the two young men met their end in a double hanging at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Justice was swift in the murder of Boise Grocer Newton Wilson. He was killed on May 8, 1950 behind his small store at 1401 E State Street, a couple of doors down from the home of Troy Powell. Walrath and Powell were arrested six hours after the murder, and by June 16 had pleaded guilty to bludgeoning and stabbing the man to death in a botched robbery. The next day they were sentenced to hang.

Having little to appeal, attorneys for the pair petitioned the Idaho Supreme Court to commute their sentences on the grounds that the State Pardon Board was illegally constituted and lacked a member who was a psychiatrist. The court didn’t buy the last-minute arguments.

When Powell and Wilson died on that Friday the 13th in 1951, it was the first hanging in Idaho since 1926. It was also the only double hanging ever carried out in the state.

The mugshots of Troy Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The mugshots of Troy Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Justice was swift in the murder of Boise Grocer Newton Wilson. He was killed on May 8, 1950 behind his small store at 1401 E State Street, a couple of doors down from the home of Troy Powell. Walrath and Powell were arrested six hours after the murder, and by June 16 had pleaded guilty to bludgeoning and stabbing the man to death in a botched robbery. The next day they were sentenced to hang.

Having little to appeal, attorneys for the pair petitioned the Idaho Supreme Court to commute their sentences on the grounds that the State Pardon Board was illegally constituted and lacked a member who was a psychiatrist. The court didn’t buy the last-minute arguments.

When Powell and Wilson died on that Friday the 13th in 1951, it was the first hanging in Idaho since 1926. It was also the only double hanging ever carried out in the state.

The mugshots of Troy Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The mugshots of Troy Powell (left) and Ernest Walrath, the only inmates ever executed in a double hanging in Idaho. Photos courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on September 24, 2019 04:00

September 23, 2019

Archie Teater

Frank Lloyd Wright designed only one home and studio for another artist. Can you guess where it is? Yes, it’s a fair bet the home is in Idaho, given the state-shaped geographical boundaries of this history series. But where in Idaho? Pssst! Say Hagerman.

Wright designed a home for Archie and Patricia Teater to be built near Hagerman in 1952. The house is perched above the Snake River just north of town. The site is called Teater’s Knoll. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house is privately owned, but occasionally opened for special events. A couple of books are available about the house, Teater’s Knoll: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Idaho Legacy and At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio.

But who was Teater? Born in 1901 in Boise, Archie Boyd Teater was a plein air landscape artist who painted mostly Western scenes. His oils were displayed alongside Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hart Benton. In his youth he worked alongside miners, trappers, and lumberjacks who probably cared little for Teater’s passion for painting, which would draw him away for days into the mountains where he would lose himself in the grandeur he meant to capture.

The Teater paintings below are owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and are on display at agency headquarters in Boise. The top painting is a view of Ritter Island, now a state park unit, from the cliffs above the island. On the bottom is a depiction of what the Thousand Springs once looked like from the island itself. A power generating structure now captures most of the flow of the springs and their once splendid beauty.

Wright designed a home for Archie and Patricia Teater to be built near Hagerman in 1952. The house is perched above the Snake River just north of town. The site is called Teater’s Knoll. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house is privately owned, but occasionally opened for special events. A couple of books are available about the house, Teater’s Knoll: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Idaho Legacy and At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio.

But who was Teater? Born in 1901 in Boise, Archie Boyd Teater was a plein air landscape artist who painted mostly Western scenes. His oils were displayed alongside Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hart Benton. In his youth he worked alongside miners, trappers, and lumberjacks who probably cared little for Teater’s passion for painting, which would draw him away for days into the mountains where he would lose himself in the grandeur he meant to capture.

The Teater paintings below are owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and are on display at agency headquarters in Boise. The top painting is a view of Ritter Island, now a state park unit, from the cliffs above the island. On the bottom is a depiction of what the Thousand Springs once looked like from the island itself. A power generating structure now captures most of the flow of the springs and their once splendid beauty.

Published on September 23, 2019 04:00

September 22, 2019

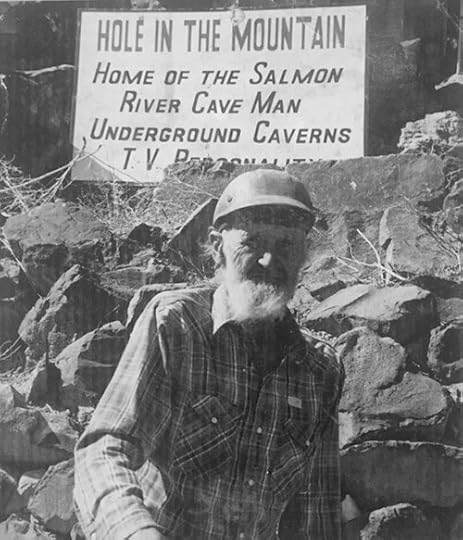

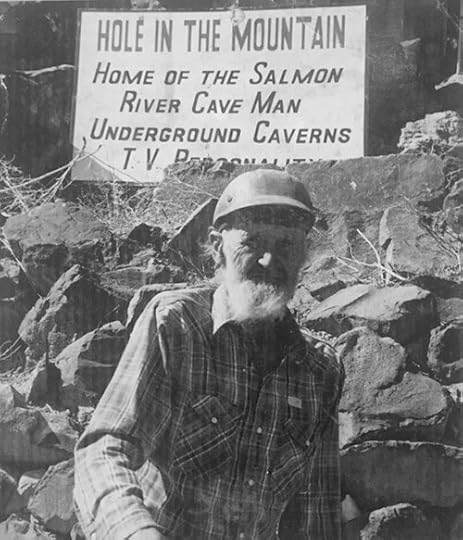

Dugout Dick

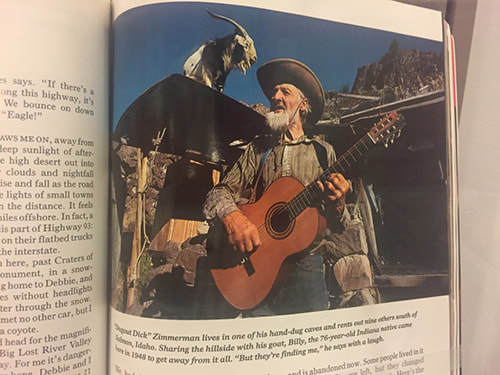

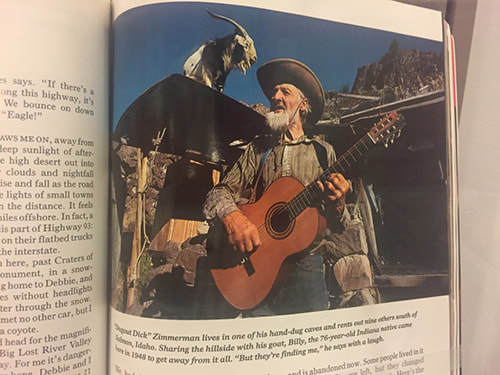

Dick Zimmerman’s story was in National Geographic and Life Magazine. He got an invitation to appear on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show and turned it down. His obituary was in the Wall Street Journal. So how did Zimmerman end up getting all that publicity and more? Well, for the latter, he had to die, but not just anyone who stops breathing makes the cut.

What Dick Zimmerman did was live in something like a cave alongside Idaho’s Salmon River.

Zimmerman had ridden the rails for a few years, bouncing around the country and working odd jobs when, at age 32, he decided to become a hermit. There may be no better place to do that than Idaho. He picked a boulder strewn slope along the river about 20 miles south of the city of Salmon.

He made himself a home by moving rocks around and forming boulder and shale walls tucked back into a rockslide with a log front. The four-room rock-sheltered house featured a natural refrigerator in back, taking advantage of a vein of ice that had formed over the centuries beneath the talus slope.

Zimmerman decided to make a little money by building more dugouts in the rocks and renting them out to people who wanted the experience of sleeping in a cave in Idaho’s backcountry. Against common sense, there was no shortage of such people.

Eventually, Zimmerman earned the name “Dugout Dick” for his 20 some rental properties scattered up and down the hillside, none of which would likely make the grade for Air B n B. He used whatever building materials he could scrounge, old tires, worn out carpeting, pieces of siding from an abandoned trailer. Floors were often concrete overlaid with linoleum scraps. Each had a wood stove and a bed or two. For windows he used scrap glass, even car windshields. The roofs were typically rough-cut logs topped with scraps of siding and carpeting and covered with sod. You could have the experience of sleeping in one of those hand-built dugouts for a couple of dollars a night, with a discount if you wanted to stay for 30 days. To get a sense of what the rentals were like, check this little YouTube podcast.

Dugout Dick married once in 1968. He met his wife through a lonely-hearts club. They corresponded, got hitched, and she came to live with him along the Salmon. She didn’t take to the life and eventually drifted away. Zimmerman later had a girlfriend from Idaho Falls, according to Cort Conley’s Idaho Loners . She spent time with Dick off and on, but came to a sad ending, murdered by her roommate in town.

Dugout Dick was less of a hermit than one might suppose. He went to town regularly, traveled a little, and didn’t live a life all that secluded. You could throw a rock from his home in the hillside across the river and nearly hit highway 93. Still, his odd lifestyle made him famous. A Scandinavian company did a documentary about the man. The magazine stories drew the curious to his “caves.”

Dick’s home, and the rentals he built, were on land under the purview of the Bureau of Land Management. While he was alive, they tolerated the ramshackle little town he had built on and in the hillside. After his death at age 94 in 2010 the BLM took down all but one of his constructions. Today there is an interpretive sign near that old dugout.

Image: Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”

Image: Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls. Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”  Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

What Dick Zimmerman did was live in something like a cave alongside Idaho’s Salmon River.

Zimmerman had ridden the rails for a few years, bouncing around the country and working odd jobs when, at age 32, he decided to become a hermit. There may be no better place to do that than Idaho. He picked a boulder strewn slope along the river about 20 miles south of the city of Salmon.

He made himself a home by moving rocks around and forming boulder and shale walls tucked back into a rockslide with a log front. The four-room rock-sheltered house featured a natural refrigerator in back, taking advantage of a vein of ice that had formed over the centuries beneath the talus slope.

Zimmerman decided to make a little money by building more dugouts in the rocks and renting them out to people who wanted the experience of sleeping in a cave in Idaho’s backcountry. Against common sense, there was no shortage of such people.

Eventually, Zimmerman earned the name “Dugout Dick” for his 20 some rental properties scattered up and down the hillside, none of which would likely make the grade for Air B n B. He used whatever building materials he could scrounge, old tires, worn out carpeting, pieces of siding from an abandoned trailer. Floors were often concrete overlaid with linoleum scraps. Each had a wood stove and a bed or two. For windows he used scrap glass, even car windshields. The roofs were typically rough-cut logs topped with scraps of siding and carpeting and covered with sod. You could have the experience of sleeping in one of those hand-built dugouts for a couple of dollars a night, with a discount if you wanted to stay for 30 days. To get a sense of what the rentals were like, check this little YouTube podcast.

Dugout Dick married once in 1968. He met his wife through a lonely-hearts club. They corresponded, got hitched, and she came to live with him along the Salmon. She didn’t take to the life and eventually drifted away. Zimmerman later had a girlfriend from Idaho Falls, according to Cort Conley’s Idaho Loners . She spent time with Dick off and on, but came to a sad ending, murdered by her roommate in town.

Dugout Dick was less of a hermit than one might suppose. He went to town regularly, traveled a little, and didn’t live a life all that secluded. You could throw a rock from his home in the hillside across the river and nearly hit highway 93. Still, his odd lifestyle made him famous. A Scandinavian company did a documentary about the man. The magazine stories drew the curious to his “caves.”

Dick’s home, and the rentals he built, were on land under the purview of the Bureau of Land Management. While he was alive, they tolerated the ramshackle little town he had built on and in the hillside. After his death at age 94 in 2010 the BLM took down all but one of his constructions. Today there is an interpretive sign near that old dugout.

Image: Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”

Image: Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”

Dugout Dick in front of a sign that advertised him as the “Salmon River Cave Man.”  Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Dugout Dick’s copy of the National Geographic magazine that featured his oddball story is on display at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls.

Published on September 22, 2019 04:00

September 21, 2019

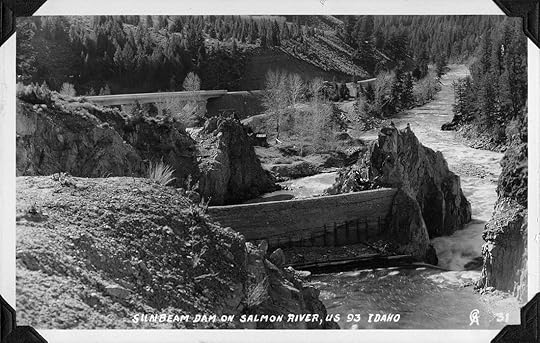

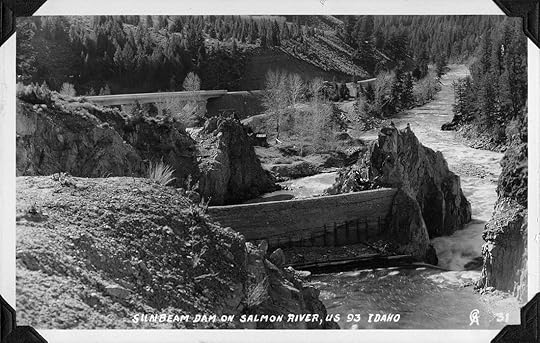

Sunbeam Dam

Today, when gathering energy from the sun through solar collectors is common, the word sunbeam as it pertains to energy is positive. The same was true in 1910 when the Sunbeam Dam was constructed on the Salmon River. It would positively power the Sunbeam mining operation up Jordan Creek from the new dam.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity, again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity, again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

Published on September 21, 2019 04:00

September 20, 2019

Slacker Records

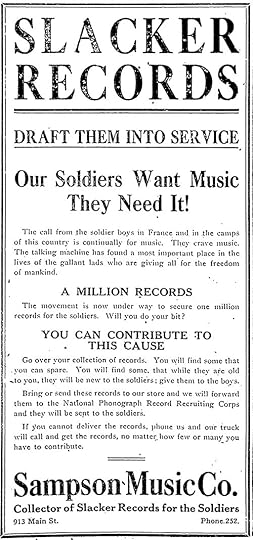

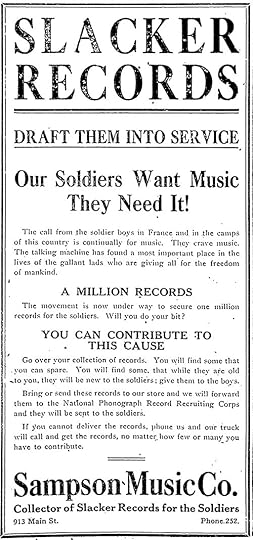

In 1918 there was a national effort to collect one million phonograph records for soldiers and sailors serving overseas. Organizers called for communities across the country to collect “slacker records.”

In Boise, the effort was led by C.B. Sampson, the music dealer who had a passion for marking what became known as the Sampson Roads.

Why “slacker”? As the Idaho Statesman article announcing the Boise drive on October 30, 1918 said, “All citizens who have records that have grown old to them are asked to contribute these records.” They were “classed as slacker records inasmuch as they are seldom played in the homes where they have been supplanted by newer records of popular music.”

Sampson started the drive off with a donation of two Victrolas and two dozen records. He also committed to have the records packed and shipped at his own expense. That first article stated that “Music is a war weapon. Army commanders have proved by experience that music is as important to the morale of the army as any single force in the soldier’s life.”

The goal was 1,000 records. On November 5, the drive was 107 records short. The article that day said that, “The donors had apparently gone through their own records, not with the idea that they would give what no longer pleased them, but what they thought would most appeal to the boys.” It ended with the note that the drive would end soon, so it would be “necessary to round up the dilatory records at once.”

The headline on November 11, 1918 read “Boise Responds Liberally in Drive for Canned Music for Boys in France.” The drive had brought in 1281 records valued at $1,102.50.

No doubt Sampson shipped the records off at once, in spite of the headlines the next day announcing that the signing of the armistice with Germany had taken place the very day the results of the slacker record drive were reported.

In Boise, the effort was led by C.B. Sampson, the music dealer who had a passion for marking what became known as the Sampson Roads.

Why “slacker”? As the Idaho Statesman article announcing the Boise drive on October 30, 1918 said, “All citizens who have records that have grown old to them are asked to contribute these records.” They were “classed as slacker records inasmuch as they are seldom played in the homes where they have been supplanted by newer records of popular music.”

Sampson started the drive off with a donation of two Victrolas and two dozen records. He also committed to have the records packed and shipped at his own expense. That first article stated that “Music is a war weapon. Army commanders have proved by experience that music is as important to the morale of the army as any single force in the soldier’s life.”

The goal was 1,000 records. On November 5, the drive was 107 records short. The article that day said that, “The donors had apparently gone through their own records, not with the idea that they would give what no longer pleased them, but what they thought would most appeal to the boys.” It ended with the note that the drive would end soon, so it would be “necessary to round up the dilatory records at once.”

The headline on November 11, 1918 read “Boise Responds Liberally in Drive for Canned Music for Boys in France.” The drive had brought in 1281 records valued at $1,102.50.

No doubt Sampson shipped the records off at once, in spite of the headlines the next day announcing that the signing of the armistice with Germany had taken place the very day the results of the slacker record drive were reported.

Published on September 20, 2019 04:00

September 19, 2019

Going Bananas in Sun Valley

Averell Harriman famously built the Sun Valley Ski Resort while he was the head of Union Pacific Railroad as a way to get wealthy travelers to buy tickets on his trains. Built in 1936, it was the first winter destination resort in the US.

But Sun Valley boasts another first, even more important to skiers. A Union Pacific engineer named James Curran designed the first chairlift and installed it at the mountain resort. It is important to note that in this case “Union Pacific engineer” does not imply a man who operated locomotives.

Curran had developed a conveyor system to load bananas onto ships. He used what he learned on that project to build the first ski lifts on Proctor and Dollar mountains. The photo shows the testing of an early prototype.

Averell Harriman deserves credit for the resort, but it’s Curran who gets credit for the first ski lift. James Curran was inducted into the National Ski Hall of Fame in 2001.

But Sun Valley boasts another first, even more important to skiers. A Union Pacific engineer named James Curran designed the first chairlift and installed it at the mountain resort. It is important to note that in this case “Union Pacific engineer” does not imply a man who operated locomotives.

Curran had developed a conveyor system to load bananas onto ships. He used what he learned on that project to build the first ski lifts on Proctor and Dollar mountains. The photo shows the testing of an early prototype.

Averell Harriman deserves credit for the resort, but it’s Curran who gets credit for the first ski lift. James Curran was inducted into the National Ski Hall of Fame in 2001.

Published on September 19, 2019 04:00

September 18, 2019

Towering

This is a story of towering historical importance. It is, perhaps, the first not-very-comprehensive account of radio towers in the Treasure Valley. It is the “good parts version” as William Golding would say, of an otherwise grindingly boring technical history that no one ever asked for. You’re welcome.

This abbreviated historical account was prompted by the installation of Idaho’s tallest radio tower. That occurred in December 2018 when KWYD installed a 605-foot tower near the Firebird Raceway to beam “Wild 101.1” into the Treasure Valley. For comparison, that’s nearly twice the height of Idaho’s tallest building, the Zion’s Bank tower in Boise which tops out at 323 feet.

I had recently run across a story about a collapsed radio tower in Boise, so decided to pluck what gems there might have been in the history of local radio towers. Though the KWYD tower going up is news, most of the news about towers occurred when they came down.

I was surprised to learn that the first radio tower story reported by the Idaho Statesman was in the March 20, 1923 issue. That was surprising, because at that time KFAU (which would later become KIDO) was a radio station project at Boise High School and the only station in Idaho. The toppling of that tiny tower would not have made headlines.

The tower that came down in 1923 was one of two huge ham radio towers at the Rawson Ranch about 16 miles southwest of Boise. The 165-foot tower collapsed in a windstorm, leaving a 200-foot tower intact. The ranch was sometimes called the Towers Ranch because H.A. Rawson, a wealthy hog farmer, was an amateur radio buff. When war broke out on April 6, 1917, Rawson was sitting at his receiving table listening to international reports. When he heard the war had begun, he “dragged off his headphones, mounted his motorcycle and was at the state house in 14 minutes” giving the news to state officials.

The next towering story came in 1933 when Nampa’s 106-foot KFXD tower came down in a windstorm.

In 1946, Boise’s third radio station, KGEM, was about to go on the air. Several things delayed the first broadcast, including the collapse of a 100-foot section of tower during construction.

KATN was the next to have tower troubles. In 1970 most of the 205-foot tower which also served sister station KBBK came down in a windstorm.

Then in 1975 one of KBOI’s directional towers crumpled in a storm, though wind was not the entire cause. Static electricity built up and arced across one of the insulators severing a guy wire. That turned the 367-foot tower into twisted metal good only for recycling.

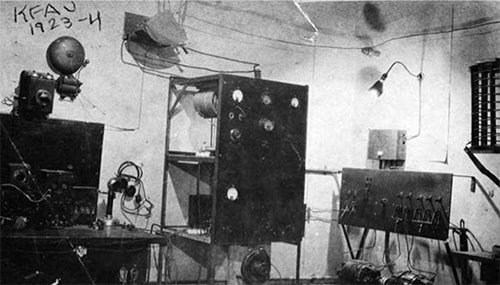

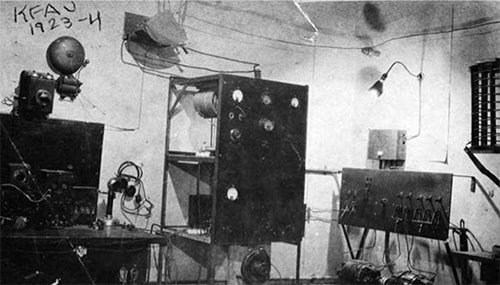

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This abbreviated historical account was prompted by the installation of Idaho’s tallest radio tower. That occurred in December 2018 when KWYD installed a 605-foot tower near the Firebird Raceway to beam “Wild 101.1” into the Treasure Valley. For comparison, that’s nearly twice the height of Idaho’s tallest building, the Zion’s Bank tower in Boise which tops out at 323 feet.

I had recently run across a story about a collapsed radio tower in Boise, so decided to pluck what gems there might have been in the history of local radio towers. Though the KWYD tower going up is news, most of the news about towers occurred when they came down.

I was surprised to learn that the first radio tower story reported by the Idaho Statesman was in the March 20, 1923 issue. That was surprising, because at that time KFAU (which would later become KIDO) was a radio station project at Boise High School and the only station in Idaho. The toppling of that tiny tower would not have made headlines.

The tower that came down in 1923 was one of two huge ham radio towers at the Rawson Ranch about 16 miles southwest of Boise. The 165-foot tower collapsed in a windstorm, leaving a 200-foot tower intact. The ranch was sometimes called the Towers Ranch because H.A. Rawson, a wealthy hog farmer, was an amateur radio buff. When war broke out on April 6, 1917, Rawson was sitting at his receiving table listening to international reports. When he heard the war had begun, he “dragged off his headphones, mounted his motorcycle and was at the state house in 14 minutes” giving the news to state officials.

The next towering story came in 1933 when Nampa’s 106-foot KFXD tower came down in a windstorm.

In 1946, Boise’s third radio station, KGEM, was about to go on the air. Several things delayed the first broadcast, including the collapse of a 100-foot section of tower during construction.

KATN was the next to have tower troubles. In 1970 most of the 205-foot tower which also served sister station KBBK came down in a windstorm.

Then in 1975 one of KBOI’s directional towers crumpled in a storm, though wind was not the entire cause. Static electricity built up and arced across one of the insulators severing a guy wire. That turned the 367-foot tower into twisted metal good only for recycling.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

KFAU was a high school radio station in 1923. The brains behind the operation belonged to Harry Redeker, PhD. He was a science teacher who advised the student broadcasters and is himself often credited as being Idaho’s first broadcaster. Some of the equipment for the Rawson Ranch radio operation was put to use at KFAU. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on September 18, 2019 04:00