Rick Just's Blog, page 188

August 28, 2019

The Second of Two Abductions

In yesterday's post I told the story of the July 1915 kidnapping of Ernest Empey who was a wealthy sheepherder. He had a ranch in Bingham County, east of Wolverine Canyon. That was where the abduction took place.

Empey escaped his kidnapper after almost a week in captivity. The man, who had asked for $6,000 in ransom, was named Leonidas Dean. He had earlier worked for Empey as a sheepherder.

With that abduction fresh in people’s minds, it is no wonder there was speculation about a connection when a second Empey went missing. Seven-year-old Alice Empey, Ernest’s niece, disappeared in April of 1916. She was last seen on her way to attend Sunday school about a mile from her home in Ammon.

Law enforcement authorities questioned Leonidas Dean about the missing girl, though he was not a suspect himself. He was serving one to ten in the Idaho State Penitentiary for the 1915 abduction.

People from communities all around turned out to search for little Alice, but to no avail. A scrap of clothing that included a button was found about a half mile from her house on Friday, April 21. The search took on a new urgency. Friends and neighbors dragged nearby Sand Creek, turning up nothing.

The April 23, 1916 Idaho Statesman reported that searchers had a new theory. Someone remembered a speeding automobile on the road by Alice’s house on the day she disappeared. Maybe they had accidentally struck her and, fearing prosecution, taken her body away and hidden it. The article said, “The search for the child or for her body is being continued far back into the hills by 200 men. If the auto accident theory is disproved there will be nothing to fall back upon save the theory that the child was kidnaped and is being held for ransom from her wealthy relatives.”

But if ransom was the goal, why wasn’t there a note? Two weeks passed and she was still missing. Three weeks passed, then four. Finally, on May 16, 1916, Alice was found. Her body was discovered on a sandbar in Sand Creek. She had not drowned.

Alice Empey, seven years old, had been assaulted and her body mutilated.

Leonidas Dean, in prison for the first Empey abduction a year before, redoubled his denials, writing, “I sympathize with the parents and friends of the murdered girl as much as anyone else and sincerely hope that the assassin may be captured. That he is no friend of mine is certain, but if he were my brother it would make no difference.”

Governor Moses Alexander announced a $1,000 reward from the State of Idaho for the apprehension and conviction of the person or persons responsible for the murder. Several suspects were questioned about the murder, then released. Suspiciously, one of the men questioned committed suicide soon after.

Luke May, a private detective from Salt Lake City, was hired to work on the case. May, sometimes called America’s Sherlock Holmes, had a reputation for using scientific methods for solving crimes. May came to believe that the person who had killed Alice was likely someone who lived off the land and rarely came in contact with people. Just such a man entered the story.

In December, dramatic news came from Hailey. Authorities there had arrested a man for attacking a young girl in her home. He was described by the Capitol News as “a veritable wild man” who had been wandering the mountains around Hailey and around Idaho Falls for the past two years “living on nothing but nuts and the flesh of game.” In the course of their interrogation they learned that Edward Ness had earlier attacked three sisters in the Hailey area, holding them as prisoners in a cabin for a time.

There was talk in Hailey of an imminent lynching, especially when word got out that Ness had confessed to the murder of Alice Empey while under interrogation by Luke May.

That seemed to solve the Alice Empey case, at least until news hit regional papers that Ness had not in fact confessed. Did he confess or did he not? Luke May, the private detective, believed Ness had confessed and had committed the murder, but the man was never charged with it. Instead, he was charged with a crime for which there was solid evidence, a brutal rape, convicted, and sentenced to 20 years in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

And, with that not-quite closure, the story of the entwined abductions of 1915 and 1916 comes to an end, with two men in jail and a family forever shaken. Officially the murder of Alice Empey remains unsolved. Edward Ness was never charged with the murder of Alice Empey, but Detective Luke May was convinced he'd done it.

Edward Ness was never charged with the murder of Alice Empey, but Detective Luke May was convinced he'd done it.

Empey escaped his kidnapper after almost a week in captivity. The man, who had asked for $6,000 in ransom, was named Leonidas Dean. He had earlier worked for Empey as a sheepherder.

With that abduction fresh in people’s minds, it is no wonder there was speculation about a connection when a second Empey went missing. Seven-year-old Alice Empey, Ernest’s niece, disappeared in April of 1916. She was last seen on her way to attend Sunday school about a mile from her home in Ammon.

Law enforcement authorities questioned Leonidas Dean about the missing girl, though he was not a suspect himself. He was serving one to ten in the Idaho State Penitentiary for the 1915 abduction.

People from communities all around turned out to search for little Alice, but to no avail. A scrap of clothing that included a button was found about a half mile from her house on Friday, April 21. The search took on a new urgency. Friends and neighbors dragged nearby Sand Creek, turning up nothing.

The April 23, 1916 Idaho Statesman reported that searchers had a new theory. Someone remembered a speeding automobile on the road by Alice’s house on the day she disappeared. Maybe they had accidentally struck her and, fearing prosecution, taken her body away and hidden it. The article said, “The search for the child or for her body is being continued far back into the hills by 200 men. If the auto accident theory is disproved there will be nothing to fall back upon save the theory that the child was kidnaped and is being held for ransom from her wealthy relatives.”

But if ransom was the goal, why wasn’t there a note? Two weeks passed and she was still missing. Three weeks passed, then four. Finally, on May 16, 1916, Alice was found. Her body was discovered on a sandbar in Sand Creek. She had not drowned.

Alice Empey, seven years old, had been assaulted and her body mutilated.

Leonidas Dean, in prison for the first Empey abduction a year before, redoubled his denials, writing, “I sympathize with the parents and friends of the murdered girl as much as anyone else and sincerely hope that the assassin may be captured. That he is no friend of mine is certain, but if he were my brother it would make no difference.”

Governor Moses Alexander announced a $1,000 reward from the State of Idaho for the apprehension and conviction of the person or persons responsible for the murder. Several suspects were questioned about the murder, then released. Suspiciously, one of the men questioned committed suicide soon after.

Luke May, a private detective from Salt Lake City, was hired to work on the case. May, sometimes called America’s Sherlock Holmes, had a reputation for using scientific methods for solving crimes. May came to believe that the person who had killed Alice was likely someone who lived off the land and rarely came in contact with people. Just such a man entered the story.

In December, dramatic news came from Hailey. Authorities there had arrested a man for attacking a young girl in her home. He was described by the Capitol News as “a veritable wild man” who had been wandering the mountains around Hailey and around Idaho Falls for the past two years “living on nothing but nuts and the flesh of game.” In the course of their interrogation they learned that Edward Ness had earlier attacked three sisters in the Hailey area, holding them as prisoners in a cabin for a time.

There was talk in Hailey of an imminent lynching, especially when word got out that Ness had confessed to the murder of Alice Empey while under interrogation by Luke May.

That seemed to solve the Alice Empey case, at least until news hit regional papers that Ness had not in fact confessed. Did he confess or did he not? Luke May, the private detective, believed Ness had confessed and had committed the murder, but the man was never charged with it. Instead, he was charged with a crime for which there was solid evidence, a brutal rape, convicted, and sentenced to 20 years in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

And, with that not-quite closure, the story of the entwined abductions of 1915 and 1916 comes to an end, with two men in jail and a family forever shaken. Officially the murder of Alice Empey remains unsolved.

Edward Ness was never charged with the murder of Alice Empey, but Detective Luke May was convinced he'd done it.

Edward Ness was never charged with the murder of Alice Empey, but Detective Luke May was convinced he'd done it.

Published on August 28, 2019 04:00

August 27, 2019

The First of Two Abductions

Some stories take a little time to tell. Today’s post will be the first of two about abductions in 1915 and 1916.

Residents of Blackfoot found out about the kidnapping of A.E. Empey on July 22, 1915, even though he was abducted on July 17. Empey had a sheep ranch in Long Valley, which is east of Wolverine Canyon in Bingham County, but his home was near Idaho Falls. Law enforcement officers in Bingham and Bonneville counties had requested the story be kept out of local papers for a time.

Alonzo Ernest Empey, who went by Ernest, was a wealthy sheepman, as were his father, E.S. Empey and his brother Harry. Ernest and Harry lived in Ammon at the time of the kidnapping. Their father lived in Garland, Utah.

Ernest, his 10-year-old son, Worth, and his son’s friend were traveling near the Empey ranch with two wagonloads of poles when they were confronted by a man brandishing a pair of six-shooters. The man marched the three at gunpoint to a small basin nearby. He gave the boys a letter he had prepared and told them to deliver it to Ernest’s father, E.S. Empey.

The boys took the letter back to the ranch house where they spent the night, waiting until Sunday morning to ride their horses into Ammon to deliver the letter and the news of the kidnapping.

The letter to E.S. Empey demanded $6,000 in ransom. The penalty for not complying with the terms of the ransom would be the death of Ernest. Shortly after the senior Empey got the phone call about the kidnapping, he left his Utah home and drove through the night to Ammon, no doubt pondering what to do.

The instructions for the ransom drop demanded that two men drive the distance of Long Valley on the road leading to Henry the following Saturday night in an open wagon. The man in front of the wagon would carry a lantern while the man in back was to have a sack of gold coins in the sum of $6,000. When they heard someone shout “Hey!” they were to drop the sack of coins in the middle of the road, turn around, and leave. If they attempted to follow, A.E. Empey would be killed. The letter said that explosives were planted strategically along the road to discourage anyone who might think of deviating from the instructions.

Meanwhile, the kidnapper had force-marched Empey to a hideout on Sheep Mountain, crashing through brush on the way and wading through streams to throw off bloodhounds. They arrived at midnight at a site about three miles from where the abduction took place. The kidnapper chained Ernest to a tree and secured the links together with a padlock.

E.S. Empey, working with the sheriff’s offices of the two counties, put out the word in the local press that he would pay the ransom. In reality that was a ruse. They had kept things quiet in the newspapers so they could organize search parties to scour the mountains near the Empey ranch.

On Sheep Mountain the kidnapper had fallen into a routine of having Ernest chain himself up at night to a quaking aspen, but setting him free during the day to move around. One day they heard some twigs snapping and brush popping. The kidnapper thrust a gun in Ernest’s face and told him to get down and be quiet. Huddled on the ground they saw two men struggling through the nearby undergrowth. Ernest recognized his brother Bert as one of the searchers.

By Friday, the day before the ransom drop was to take place, the kidnapper and Ernest had gotten quite chummy. The kidnapper said that he wanted to catch some sleep and would chain his captive to the tree. Ernest said, “Ah, don’t do it. It is too lonesome sitting here on the end of a chain. Sit up and let’s talk.”

The kidnapper assented. They talked and talked until the man got drowsy. He lay on his bedding with a gun in his hand facing Empey. Eventually the kidnapper closed his eyes. Ernest got up, gathered a few sticks to make a fire, and moved around venturing a little further from camp picking up wood. After a few minutes of stirring around he determined that the kidnapper was truly asleep. He began a mad dash down the mountain, running smack into two aspens and a pine tree before determining that he had to run and watch where he was going.

The kidnapper woke up a few minutes after Ernest left the camp. He hiked to the nearest cabin searching for Empey. By the time he reached the cabin Empey had made his way to a sawmill and the word had gone out about the kidnapper. The residents at the cabin were ready for the man. When he was within a few steps of the yard the men of the Coumerilh cabin drew their guns and told the kidnapper to throw up his hands. He hesitated. Mrs. Coumerilh, standing in the door of the cabin, lost her patience and fired a shot at him, putting a hole through his hat.

The kidnapper turned out the be a sheepherder who had worked for Empey briefly five years before the abduction. Leonidas Dean had quit his job when Empey had threatened to shoot Dean’s dog because it was nipping at sheep. It wasn’t revenge Dean was after, though. It was simply money.

“I took this means of getting money as I thought I could do more good with it than those who had it,” Dean explained. He said he had no intention of harming Empey if the ransom were not paid.

Dean was convicted of kidnaping and sentenced to from one to ten years in prison. While in the Idaho State Penitentiary in Boise, the man would emphatically deny that he had anything to do with the second Empey abduction, this one in 1916. But that’s a story for tomorrow.

Alonzo Ernest Empey.

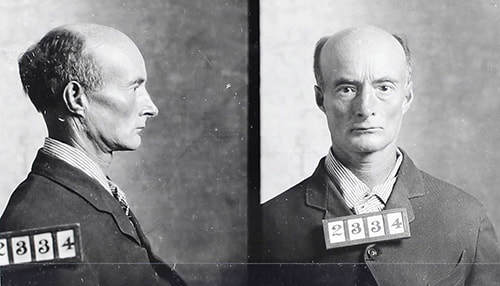

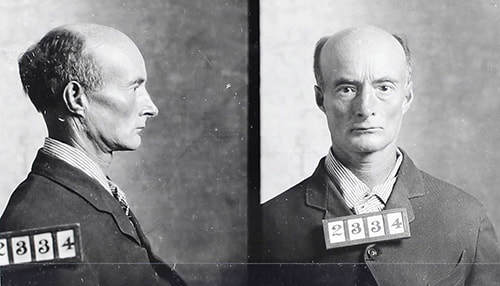

Alonzo Ernest Empey.  Convicted kidnapper Leonidas Dean.

Convicted kidnapper Leonidas Dean.

Residents of Blackfoot found out about the kidnapping of A.E. Empey on July 22, 1915, even though he was abducted on July 17. Empey had a sheep ranch in Long Valley, which is east of Wolverine Canyon in Bingham County, but his home was near Idaho Falls. Law enforcement officers in Bingham and Bonneville counties had requested the story be kept out of local papers for a time.

Alonzo Ernest Empey, who went by Ernest, was a wealthy sheepman, as were his father, E.S. Empey and his brother Harry. Ernest and Harry lived in Ammon at the time of the kidnapping. Their father lived in Garland, Utah.

Ernest, his 10-year-old son, Worth, and his son’s friend were traveling near the Empey ranch with two wagonloads of poles when they were confronted by a man brandishing a pair of six-shooters. The man marched the three at gunpoint to a small basin nearby. He gave the boys a letter he had prepared and told them to deliver it to Ernest’s father, E.S. Empey.

The boys took the letter back to the ranch house where they spent the night, waiting until Sunday morning to ride their horses into Ammon to deliver the letter and the news of the kidnapping.

The letter to E.S. Empey demanded $6,000 in ransom. The penalty for not complying with the terms of the ransom would be the death of Ernest. Shortly after the senior Empey got the phone call about the kidnapping, he left his Utah home and drove through the night to Ammon, no doubt pondering what to do.

The instructions for the ransom drop demanded that two men drive the distance of Long Valley on the road leading to Henry the following Saturday night in an open wagon. The man in front of the wagon would carry a lantern while the man in back was to have a sack of gold coins in the sum of $6,000. When they heard someone shout “Hey!” they were to drop the sack of coins in the middle of the road, turn around, and leave. If they attempted to follow, A.E. Empey would be killed. The letter said that explosives were planted strategically along the road to discourage anyone who might think of deviating from the instructions.

Meanwhile, the kidnapper had force-marched Empey to a hideout on Sheep Mountain, crashing through brush on the way and wading through streams to throw off bloodhounds. They arrived at midnight at a site about three miles from where the abduction took place. The kidnapper chained Ernest to a tree and secured the links together with a padlock.

E.S. Empey, working with the sheriff’s offices of the two counties, put out the word in the local press that he would pay the ransom. In reality that was a ruse. They had kept things quiet in the newspapers so they could organize search parties to scour the mountains near the Empey ranch.

On Sheep Mountain the kidnapper had fallen into a routine of having Ernest chain himself up at night to a quaking aspen, but setting him free during the day to move around. One day they heard some twigs snapping and brush popping. The kidnapper thrust a gun in Ernest’s face and told him to get down and be quiet. Huddled on the ground they saw two men struggling through the nearby undergrowth. Ernest recognized his brother Bert as one of the searchers.

By Friday, the day before the ransom drop was to take place, the kidnapper and Ernest had gotten quite chummy. The kidnapper said that he wanted to catch some sleep and would chain his captive to the tree. Ernest said, “Ah, don’t do it. It is too lonesome sitting here on the end of a chain. Sit up and let’s talk.”

The kidnapper assented. They talked and talked until the man got drowsy. He lay on his bedding with a gun in his hand facing Empey. Eventually the kidnapper closed his eyes. Ernest got up, gathered a few sticks to make a fire, and moved around venturing a little further from camp picking up wood. After a few minutes of stirring around he determined that the kidnapper was truly asleep. He began a mad dash down the mountain, running smack into two aspens and a pine tree before determining that he had to run and watch where he was going.

The kidnapper woke up a few minutes after Ernest left the camp. He hiked to the nearest cabin searching for Empey. By the time he reached the cabin Empey had made his way to a sawmill and the word had gone out about the kidnapper. The residents at the cabin were ready for the man. When he was within a few steps of the yard the men of the Coumerilh cabin drew their guns and told the kidnapper to throw up his hands. He hesitated. Mrs. Coumerilh, standing in the door of the cabin, lost her patience and fired a shot at him, putting a hole through his hat.

The kidnapper turned out the be a sheepherder who had worked for Empey briefly five years before the abduction. Leonidas Dean had quit his job when Empey had threatened to shoot Dean’s dog because it was nipping at sheep. It wasn’t revenge Dean was after, though. It was simply money.

“I took this means of getting money as I thought I could do more good with it than those who had it,” Dean explained. He said he had no intention of harming Empey if the ransom were not paid.

Dean was convicted of kidnaping and sentenced to from one to ten years in prison. While in the Idaho State Penitentiary in Boise, the man would emphatically deny that he had anything to do with the second Empey abduction, this one in 1916. But that’s a story for tomorrow.

Alonzo Ernest Empey.

Alonzo Ernest Empey.  Convicted kidnapper Leonidas Dean.

Convicted kidnapper Leonidas Dean.

Published on August 27, 2019 04:00

August 26, 2019

Hogan the Stiff

This all started form me when I saw a photo of James Hogan and a brief story about his tragic life in the book

Legendary Locals of Boise

, by Barbara Perry Bauer and Elizabeth Jacox. I decided to do a little research on the man. Sifting through old papers I found story after story, most numbingly familiar.

In September of 1880, the Idaho World, which was published in Idaho City, said that “James Hogan, better known as Hogan the Gambler, was brought before a probate judge on a charge of stealing four hundred cigars. The judge fined Hogan $100 and gave him twenty-five days in jail for silent meditation on the fact that “Honesty is the best policy.”

Then, in March of, 1883, the same newspaper quoted Hogan as saying, “When I’ve money, I’m Hogan the Gambler; but when I’m broke I’m Hogan the shtiff!”

The Statesman first mentioned Hogan in January 1888. The article read, “Hogan the stiff;” as the city marshal calls him, has been locked up in the city jail for the past three or four days. He was drunk and disorderly at various times and places and hence locked up until he became sobered.”

In 1889, Jimmy made the paper twice. Both stories were in a faux formal style. In October, the report was that “Friday evening, Officer Haas invited Mr. Hogan of this city, to pass the night in the city lodging house on Eighth Street. The invitation was accepted in the spirit in which it was tendered.” The “lodging house” on Eighth was the city jail.

Then, just a month later there appeared the following: “A celebrity known here as Hogan has been the guest of the city and entertained for several weeks past at the city lodging house on Eighth street, left the city on the Idaho Central passenger train Wednesday evening for Nampa, where he took the west bound train of the Oregon Short Line for Tilamock Head and points further west. Mr. Hogan had intimated to the City Marshal that he needed a change of scene and diet, when “Old Nick” very courteously and kindly escorted him to the railroad depot on the other side of the river, where both took the train for Nampa. At Nampa, the parting scene took place, Mr. Hogan promising the marshal that he would write to him and to all his friends in Boise as soon as he reached his destination. “

Hogan stayed out of trouble, or perhaps, stayed out of Boise for about a year. A thorough search of other newspapers might locate him. In October, 1891 the Statesman reported simply that “Hogan the Stiff got drunk again yesterday and was taken in by Marshall Nicholson.’

In 1892, he got four mentions in the paper. He paid a $9 fine, served 20 days in jail for stealing a coat from a restaurant, was called by the Statesman “Boise’s boss boozer,’ and shipped out as the cook for the Idaho National Guard, which had been dispatched to Wallace to quell the union troubles in the mines up there. It was the fond hope of some in Boise that the guard would forget to bring him back home when they returned. The boys liked his cooking. They took up a collection to get him a new suit of clothes, and when they returned to Boise, James Hogan came back with them.

1894 was a banner year for James Hogan. A blurb said, “It is only a matter of time until Hogan the stiff will become a permanent county charge. He was only recently discharged from the county jail after serving a lengthy sentence for vagrancy, and yesterday Judge Clark sent him up for 70 days on the same charge.

A little later the Statesman reported that “Hogan, Boise’s veteran “bummer,” has been sent to the poor farm. Hogan said the only objection he had to going to the farm was because there were too many bums there. He didn’t like to associate with them.

A 90-day sentence. A 70-day sentence. The math was daunting for Jimmy in 1894. He would sometimes be out less than a day before being arrested again that year. Then there were the stolen shoes. Another inmate escaped with Hogan’s shoes. Jimmy commented that that’s what one gets for associating with a depraved set of men.

His big year was topped off when the Caldwell Tribune reported that “While Hogan the Stiff was delivering a speech against the Republican party on Main Street at a late hour Wednesday night he was shot at and barely missed, the bullet striking within a few feet of him.” The report came out on Christmas Day, so 1894 was about over.

James Hogan was usually listed as a cook, and sometimes as a waiter. He apparently also worked for a time at the Idaho statehouse, possibly as a janitor.

Hogan was political, in a ranting-at-the-Republicans sort of way. He was one of many prisoners who signed a petition for a breakaway group of Democrats while in jail. In 1896 Hogan expressed his regrets from jail that he would not be able to help Democratic electors. One wonders if that feeling was mutual.

In 1897 Hogan was in the paper as the victim of crime, not as a low-level perpetrator. One John Murphy was arrested for robbing Hogan. The paper couldn’t resist a dig, saying “No one would suppose that Hogan would have money for anyone to steal, but it is said he has been working and recently came into town with considerable cash.” Later that year, he was back in jail for being a common drunkard. He caused some mirth in the courtroom speaking in his own defense when he accused witnesses of being “worse drunkards nor he had been.”

Over the next ten years, Hogan was arrested at least 41 times, and the Statesman duly reported each instance.

I’ll just tell you about a couple. In 1900 a convention came to town. Conventioneers were each given a little badge that said Freedom of the City. About the time the convention broke up, Jimmy had been released from jail and told to leave town within 24 hours. But he found one of those Freedom of the City badges, pinned it on, and proceeded to act like it meant something. He said it was now “without the power of man to arrest him or otherwise deprive him of his liberty.” Jimmy was prone to make windy speeches about politics when he was well-lubricated, and this day he stationed himself on Main street and began to pontificate. To his surprise he felt the strong hand of the law on his collar and was whisked away to jail, protesting about the injustice all the way because, after all, he was wearing that pin. He got another 60 days for that one.

In 1903, the Statesman ran an unusually lengthy article about Hogan, pointing out that he had spent seven months of the past year in jail on long sentences, and that didn’t count the several short stints when he was there to just sleep it off.

In 1907 Hogan threw a brick at a phonograph in a tobacco store on Main Street, destroying it. He said the voices coming from the machine were calling him names.

That same year, in September, the headline was “Happy J. Hogan Leaves County Jail.” After serving his “forty-eleventh term in jail” Hogan had packed up his grip but left it with the deputy to take care of, saying he might as well keep it at the jail since he spent more time there than anywhere else.

Upon his departure deputies were watching him walk down the street. He turned and said, “Goodbye to ye, byes; don’t cry for me departure. Hogan the stiff will never desar-rt year. I’ll be back soon; never fear.”

The article ended with the line, “And he is expected.”

But he did not come back. The October 2, 1907 issue of the Statesman had a story about Hogan with a different tone. Hogan had passed away. No more Hogan the stiff, in this story. It read, “The deceased was about 65 years of age and resided in and around Boise for at least 30 years. He was a well-known character and friend to everybody in his humble way, while all who knew him were his friends. In late years it was through friendship that Hogan lived. Many gave him money and he was seldom found without some change in his pockets.”

The paper went on to say that many who had given him money to buy food would make up a purse to defray funeral expenses, and a special fund was being collected to buy flowers.

A crude concrete headstone marked his grave for 111 years. You’d have to get down on your hands and knees to read it.

I included a picture of his gravesite from the Find a Grave website when I first wrote about Jimmy in 2018. The photographer had tossed a red file folder over the little headstone to mark his grave for the photo. When people saw that, someone suggest that we get him a nice grave marker.

I did a little Go Fund Me campaign and in three or four days we had enough for an engraved stone marker, thanks to the generosity of Boise Valley Monument.

I’ll end this by explaining why the marker says what it does. You’d expect the dates of birth and death, of course. The epitaph is because of yet another Statesman article about Jimmy. The headline said “Just Plain Jimmy.” They quoted him saying to a reporter “Whin ye go up there to the Statesman office and write this up, please it jist plain Jimmy, and not Hogan the Stiff.

So, 111 years later, Jimmy got his wish. A toast to Just Plain Jimmy, 2018.

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time.

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time.

In September of 1880, the Idaho World, which was published in Idaho City, said that “James Hogan, better known as Hogan the Gambler, was brought before a probate judge on a charge of stealing four hundred cigars. The judge fined Hogan $100 and gave him twenty-five days in jail for silent meditation on the fact that “Honesty is the best policy.”

Then, in March of, 1883, the same newspaper quoted Hogan as saying, “When I’ve money, I’m Hogan the Gambler; but when I’m broke I’m Hogan the shtiff!”

The Statesman first mentioned Hogan in January 1888. The article read, “Hogan the stiff;” as the city marshal calls him, has been locked up in the city jail for the past three or four days. He was drunk and disorderly at various times and places and hence locked up until he became sobered.”

In 1889, Jimmy made the paper twice. Both stories were in a faux formal style. In October, the report was that “Friday evening, Officer Haas invited Mr. Hogan of this city, to pass the night in the city lodging house on Eighth Street. The invitation was accepted in the spirit in which it was tendered.” The “lodging house” on Eighth was the city jail.

Then, just a month later there appeared the following: “A celebrity known here as Hogan has been the guest of the city and entertained for several weeks past at the city lodging house on Eighth street, left the city on the Idaho Central passenger train Wednesday evening for Nampa, where he took the west bound train of the Oregon Short Line for Tilamock Head and points further west. Mr. Hogan had intimated to the City Marshal that he needed a change of scene and diet, when “Old Nick” very courteously and kindly escorted him to the railroad depot on the other side of the river, where both took the train for Nampa. At Nampa, the parting scene took place, Mr. Hogan promising the marshal that he would write to him and to all his friends in Boise as soon as he reached his destination. “

Hogan stayed out of trouble, or perhaps, stayed out of Boise for about a year. A thorough search of other newspapers might locate him. In October, 1891 the Statesman reported simply that “Hogan the Stiff got drunk again yesterday and was taken in by Marshall Nicholson.’

In 1892, he got four mentions in the paper. He paid a $9 fine, served 20 days in jail for stealing a coat from a restaurant, was called by the Statesman “Boise’s boss boozer,’ and shipped out as the cook for the Idaho National Guard, which had been dispatched to Wallace to quell the union troubles in the mines up there. It was the fond hope of some in Boise that the guard would forget to bring him back home when they returned. The boys liked his cooking. They took up a collection to get him a new suit of clothes, and when they returned to Boise, James Hogan came back with them.

1894 was a banner year for James Hogan. A blurb said, “It is only a matter of time until Hogan the stiff will become a permanent county charge. He was only recently discharged from the county jail after serving a lengthy sentence for vagrancy, and yesterday Judge Clark sent him up for 70 days on the same charge.

A little later the Statesman reported that “Hogan, Boise’s veteran “bummer,” has been sent to the poor farm. Hogan said the only objection he had to going to the farm was because there were too many bums there. He didn’t like to associate with them.

A 90-day sentence. A 70-day sentence. The math was daunting for Jimmy in 1894. He would sometimes be out less than a day before being arrested again that year. Then there were the stolen shoes. Another inmate escaped with Hogan’s shoes. Jimmy commented that that’s what one gets for associating with a depraved set of men.

His big year was topped off when the Caldwell Tribune reported that “While Hogan the Stiff was delivering a speech against the Republican party on Main Street at a late hour Wednesday night he was shot at and barely missed, the bullet striking within a few feet of him.” The report came out on Christmas Day, so 1894 was about over.

James Hogan was usually listed as a cook, and sometimes as a waiter. He apparently also worked for a time at the Idaho statehouse, possibly as a janitor.

Hogan was political, in a ranting-at-the-Republicans sort of way. He was one of many prisoners who signed a petition for a breakaway group of Democrats while in jail. In 1896 Hogan expressed his regrets from jail that he would not be able to help Democratic electors. One wonders if that feeling was mutual.

In 1897 Hogan was in the paper as the victim of crime, not as a low-level perpetrator. One John Murphy was arrested for robbing Hogan. The paper couldn’t resist a dig, saying “No one would suppose that Hogan would have money for anyone to steal, but it is said he has been working and recently came into town with considerable cash.” Later that year, he was back in jail for being a common drunkard. He caused some mirth in the courtroom speaking in his own defense when he accused witnesses of being “worse drunkards nor he had been.”

Over the next ten years, Hogan was arrested at least 41 times, and the Statesman duly reported each instance.

I’ll just tell you about a couple. In 1900 a convention came to town. Conventioneers were each given a little badge that said Freedom of the City. About the time the convention broke up, Jimmy had been released from jail and told to leave town within 24 hours. But he found one of those Freedom of the City badges, pinned it on, and proceeded to act like it meant something. He said it was now “without the power of man to arrest him or otherwise deprive him of his liberty.” Jimmy was prone to make windy speeches about politics when he was well-lubricated, and this day he stationed himself on Main street and began to pontificate. To his surprise he felt the strong hand of the law on his collar and was whisked away to jail, protesting about the injustice all the way because, after all, he was wearing that pin. He got another 60 days for that one.

In 1903, the Statesman ran an unusually lengthy article about Hogan, pointing out that he had spent seven months of the past year in jail on long sentences, and that didn’t count the several short stints when he was there to just sleep it off.

In 1907 Hogan threw a brick at a phonograph in a tobacco store on Main Street, destroying it. He said the voices coming from the machine were calling him names.

That same year, in September, the headline was “Happy J. Hogan Leaves County Jail.” After serving his “forty-eleventh term in jail” Hogan had packed up his grip but left it with the deputy to take care of, saying he might as well keep it at the jail since he spent more time there than anywhere else.

Upon his departure deputies were watching him walk down the street. He turned and said, “Goodbye to ye, byes; don’t cry for me departure. Hogan the stiff will never desar-rt year. I’ll be back soon; never fear.”

The article ended with the line, “And he is expected.”

But he did not come back. The October 2, 1907 issue of the Statesman had a story about Hogan with a different tone. Hogan had passed away. No more Hogan the stiff, in this story. It read, “The deceased was about 65 years of age and resided in and around Boise for at least 30 years. He was a well-known character and friend to everybody in his humble way, while all who knew him were his friends. In late years it was through friendship that Hogan lived. Many gave him money and he was seldom found without some change in his pockets.”

The paper went on to say that many who had given him money to buy food would make up a purse to defray funeral expenses, and a special fund was being collected to buy flowers.

A crude concrete headstone marked his grave for 111 years. You’d have to get down on your hands and knees to read it.

I included a picture of his gravesite from the Find a Grave website when I first wrote about Jimmy in 2018. The photographer had tossed a red file folder over the little headstone to mark his grave for the photo. When people saw that, someone suggest that we get him a nice grave marker.

I did a little Go Fund Me campaign and in three or four days we had enough for an engraved stone marker, thanks to the generosity of Boise Valley Monument.

I’ll end this by explaining why the marker says what it does. You’d expect the dates of birth and death, of course. The epitaph is because of yet another Statesman article about Jimmy. The headline said “Just Plain Jimmy.” They quoted him saying to a reporter “Whin ye go up there to the Statesman office and write this up, please it jist plain Jimmy, and not Hogan the Stiff.

So, 111 years later, Jimmy got his wish. A toast to Just Plain Jimmy, 2018.

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time.

That's James Hogan on the left standing for a photo with the Idaho Legislature. He worked as a janitor in the capitol at one time.

Published on August 26, 2019 04:00

August 25, 2019

In the Beginning...

If you’re looking for that one moment when Idaho began, you could do worse than picking the second the sun first glinted off a speck of gold in the pan of W.F. Bassett in August of 1860. But let’s not give all credit to that one man, one among a handful of prospectors who might have come up with that three-cents-worth of ore that marked the beginning of the gold rush in what is today Northern Idaho. Let’s step back and honor the woman who led the men there to seek their fortune in the first place. That woman was Jane Timothy, 18-year-old daughter of Chief Timothy who the Nez Perce knew better as Ta-moot-sin. Top of Form

Jane was known by many names among those in her tribe, Princess Like the Fawn, Princess Like the Dove, Princess Like Running Water, according to L.E. Bragg’s book, Idaho’s Remarkable Women . Jane’s uncle was Old Chief Joseph, so she was a cousin of the Chief Joseph who outwitted the military time after time in 1877.

But this was before that time. It was a time when, by treaty, whites weren’t allowed on the Nez Perce reservation without permission. Many of the Tribe were adamant about not letting white men into their home lands, but Chief Timothy had long been a friend of the whites.

So, when Elias D. Pierce approached the chief about helping him find his way into the back country to search for gold, Chief Timothy was amenable. Timothy knew that other tribal members had told Pierce and his party of six to turn back more than once and that they were watching the party with suspicion. He reasoned that they were also watching Timothy’s men to make sure they did not help Pierce.

There was a roundabout way to get into the country Pierce wanted to explore. They would need someone who knew the trail well. With the men being closely watched, who could serve as guide to the Pierce party? Jane spoke up. She knew the trail as well as anyone and volunteered to show the prospectors the way.

Pierce and his men made a show of beginning a trek by turning back east away from the reservation. At night, they doubled back and met up with Jane who lead them to the trail. She was stealthy, taking the men on a parallel path so that no one would find any sign of their passage. They traveled at night and listened to Jane when she told them how to move silently through the brush to avoid detection.

Jane “knew every hill and stream, every mountain meadow and possible camping place; almost she knew the very trees,” wrote W.A. Goulder, an early pioneer, in his 1909 Reminiscences.

Once word got out about the find on Orofino Creek (named such for the “fine gold” panned there), prospectors came to the country in numbers too large for the Nez Perce to deal with. They were overwhelmed by the inevitable rush.

There is little doubt the Pierce party would not have made it to what would become the townsite of Pierce without the help of Jane Timothy. Pierce, who had an elevated opinion of his own prowess in all things, failed to mention her at all in his writings. He noted that, “We procured a guide who was familiar with the country.” That it has been Wilbur Bassett who found the first sparkle of gold also went un-noted by Pierce.

Jane Timothy met and married the Harvard-educated John Silcott not long after leading the Pierce Party to their historical find. They would later operate the first commercial ferry across the Clearwater. Jane Timothy Silcott

Jane Timothy Silcott  The marker for Jane Timothy Silcott’s grave is on private property just off Down River Road, Lewiston.

The marker for Jane Timothy Silcott’s grave is on private property just off Down River Road, Lewiston.  John Silcott.

John Silcott.

Jane was known by many names among those in her tribe, Princess Like the Fawn, Princess Like the Dove, Princess Like Running Water, according to L.E. Bragg’s book, Idaho’s Remarkable Women . Jane’s uncle was Old Chief Joseph, so she was a cousin of the Chief Joseph who outwitted the military time after time in 1877.

But this was before that time. It was a time when, by treaty, whites weren’t allowed on the Nez Perce reservation without permission. Many of the Tribe were adamant about not letting white men into their home lands, but Chief Timothy had long been a friend of the whites.

So, when Elias D. Pierce approached the chief about helping him find his way into the back country to search for gold, Chief Timothy was amenable. Timothy knew that other tribal members had told Pierce and his party of six to turn back more than once and that they were watching the party with suspicion. He reasoned that they were also watching Timothy’s men to make sure they did not help Pierce.

There was a roundabout way to get into the country Pierce wanted to explore. They would need someone who knew the trail well. With the men being closely watched, who could serve as guide to the Pierce party? Jane spoke up. She knew the trail as well as anyone and volunteered to show the prospectors the way.

Pierce and his men made a show of beginning a trek by turning back east away from the reservation. At night, they doubled back and met up with Jane who lead them to the trail. She was stealthy, taking the men on a parallel path so that no one would find any sign of their passage. They traveled at night and listened to Jane when she told them how to move silently through the brush to avoid detection.

Jane “knew every hill and stream, every mountain meadow and possible camping place; almost she knew the very trees,” wrote W.A. Goulder, an early pioneer, in his 1909 Reminiscences.

Once word got out about the find on Orofino Creek (named such for the “fine gold” panned there), prospectors came to the country in numbers too large for the Nez Perce to deal with. They were overwhelmed by the inevitable rush.

There is little doubt the Pierce party would not have made it to what would become the townsite of Pierce without the help of Jane Timothy. Pierce, who had an elevated opinion of his own prowess in all things, failed to mention her at all in his writings. He noted that, “We procured a guide who was familiar with the country.” That it has been Wilbur Bassett who found the first sparkle of gold also went un-noted by Pierce.

Jane Timothy met and married the Harvard-educated John Silcott not long after leading the Pierce Party to their historical find. They would later operate the first commercial ferry across the Clearwater.

Jane Timothy Silcott

Jane Timothy Silcott  The marker for Jane Timothy Silcott’s grave is on private property just off Down River Road, Lewiston.

The marker for Jane Timothy Silcott’s grave is on private property just off Down River Road, Lewiston.  John Silcott.

John Silcott.

Published on August 25, 2019 04:00

August 24, 2019

Idaho's Ivy League

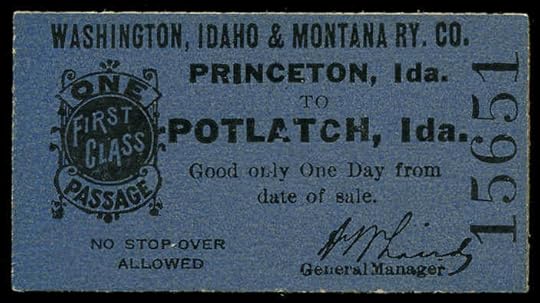

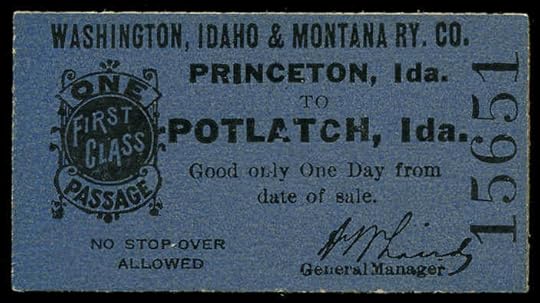

Looking for a good education? You might consider Purdue, Princeton, Harvard, Yale, or Cornell. They're all Ivy League universities, and they're all places in Idaho. All those sites are along the old Washington, Idaho, and Montana Railroad in north Idaho. You'll also find Wellesley, Vassar, and Stanford along the 47-mile-stretch of railroad.

The tradition of naming places along that route after colleges apparently started when railroad officials offered to name one site for a local man, Homer Canfield. He suggested they name the place Harvard, instead. An engineer named a siding Purdue, after his alma mater, and the die was cast. Students working summer jobs set about naming various sidings after their colleges.

Cambridge, Idaho, in Washington County, also owes its name to a railroad and Harvard University. Harvard was the alma mater of the president of the Pacific and Idaho Northern Railroad, and of course, Harvard is in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

And what about Oxford? Surely that's a good choice to receive your advanced degree? In England, that's true, but in Idaho, Oxford is a site a few miles north of Preston. It wasn't named after the university at all. Oxford was named because some oxen forded the creek there.

You can learn something at any of these Idaho sites, but none of them, as far as I know, offer advanced degrees.

The tradition of naming places along that route after colleges apparently started when railroad officials offered to name one site for a local man, Homer Canfield. He suggested they name the place Harvard, instead. An engineer named a siding Purdue, after his alma mater, and the die was cast. Students working summer jobs set about naming various sidings after their colleges.

Cambridge, Idaho, in Washington County, also owes its name to a railroad and Harvard University. Harvard was the alma mater of the president of the Pacific and Idaho Northern Railroad, and of course, Harvard is in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

And what about Oxford? Surely that's a good choice to receive your advanced degree? In England, that's true, but in Idaho, Oxford is a site a few miles north of Preston. It wasn't named after the university at all. Oxford was named because some oxen forded the creek there.

You can learn something at any of these Idaho sites, but none of them, as far as I know, offer advanced degrees.

Published on August 24, 2019 04:00

August 23, 2019

The Iron Door Mine

Stories of lost gold abound in Idaho, whether they’re about that mine that a prospector told of with his last dying breath, or stagecoach loot secreted away in some crevice, they usually have just enough detail to make them intriguingly plausible.

The detail that defines the Mine with the Iron Door story is, not surprisingly, that iron door. Before I get into the telling of the Idaho story, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that there are many such stories about lost mines in the Southwest that are hidden behind an iron door. There was a romance called The Mine with the Iron Door written by Harold Bell Right in 1923. It was made into a silent movie the following year, then remade as a talkie in 1934.

Most stories about the lost mine in the Southwest place it in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson. That mine has been lost a very long time, with the legends dating back to when the Spanish reigned over the region.

But the Mine with the Iron Door we’re concerned about today is allegedly located somewhere on Samaria Mountain near Malad City. The story has something most of the other iron door stories lack, the genesis of the door. It seems a bank in some Utah town—maybe Corinne, which was a major hub in the latter part of the 19th Century—burned down, leaving little that was salvageable, but the iron door used for its vault.

A trio of robbers planning to make off with stagecoach gold acquired that door thinking it would be a fine way to hide their loot. They found a cave on Samaria Mountain—need I say allegedly quite a lot during this telling? Let’s assume you can insert that where it needs to be, which is in approximately every sentence. Anyway, they installed the vault door in this cave, maybe part way down inside it so that the door was hidden.

Now that they had their own private “bank” the robbers did what robbers do. They robbed a stage and took quite a lot of bars of gold or coins or Bitcoins back to Samaria Mountain to secret away in their safe.

Befitting of a lost gold story, the robbers had a row resulting in them shooting each other, every last one. Though all were wounded, one got out and locked his co-conspirators in the cave behind the Iron Door. He found his way to a ranch where, knowing he was on death’s door, he blurted out his story, then stepped through the door at the end of his life, one that was presumably not iron.

But the story gets better. A few years later a young boy found the iron door! He’d heard the story of the robbery and knew he was about to be rich but—isn’t luck always like this?—he got lost himself during a storm. He was found, of course, and told of the iron door, which he was never able to find again.

Thomas J. McDevitt, MD, tells this and many other entertaining stories in his book, Idaho’s Malad Valley, a History . He even reveals the name of the boy, who grew to be a man, then an old man who never tired of telling it. He was known for telling some tall tales as well, but this one was surely true.

Now, that big hunk of iron shouldn’t be so difficult to find today with metal detecting technology constantly improving, and there is no shortage of people willing to try.

But, before you start packing for a trip to Samaria, you might ask yourself this question: Why would anyone go to the trouble of installing a heavy iron door in a cave to hide his loot? Simply hiding the gold in the cave would seem better than putting in a door that all but said, “Break this lock, for behind this door is something of value.”

I should also note that there’s a fair chance you might run into an IRON DOOR AT THE MOUTH OF A CAVE in Idaho. Look closely there’s probably a sign on it that warns it is dangerous to enter unless you are an experienced spelunker. Also, it’s more likely to be a gate than a door, with plenty of room to let bats fly out at night and discover their own treasure.

Tempting, perhaps, but you're more likely to find bats behind this iron door that gold.

Tempting, perhaps, but you're more likely to find bats behind this iron door that gold.

The detail that defines the Mine with the Iron Door story is, not surprisingly, that iron door. Before I get into the telling of the Idaho story, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that there are many such stories about lost mines in the Southwest that are hidden behind an iron door. There was a romance called The Mine with the Iron Door written by Harold Bell Right in 1923. It was made into a silent movie the following year, then remade as a talkie in 1934.

Most stories about the lost mine in the Southwest place it in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson. That mine has been lost a very long time, with the legends dating back to when the Spanish reigned over the region.

But the Mine with the Iron Door we’re concerned about today is allegedly located somewhere on Samaria Mountain near Malad City. The story has something most of the other iron door stories lack, the genesis of the door. It seems a bank in some Utah town—maybe Corinne, which was a major hub in the latter part of the 19th Century—burned down, leaving little that was salvageable, but the iron door used for its vault.

A trio of robbers planning to make off with stagecoach gold acquired that door thinking it would be a fine way to hide their loot. They found a cave on Samaria Mountain—need I say allegedly quite a lot during this telling? Let’s assume you can insert that where it needs to be, which is in approximately every sentence. Anyway, they installed the vault door in this cave, maybe part way down inside it so that the door was hidden.

Now that they had their own private “bank” the robbers did what robbers do. They robbed a stage and took quite a lot of bars of gold or coins or Bitcoins back to Samaria Mountain to secret away in their safe.

Befitting of a lost gold story, the robbers had a row resulting in them shooting each other, every last one. Though all were wounded, one got out and locked his co-conspirators in the cave behind the Iron Door. He found his way to a ranch where, knowing he was on death’s door, he blurted out his story, then stepped through the door at the end of his life, one that was presumably not iron.

But the story gets better. A few years later a young boy found the iron door! He’d heard the story of the robbery and knew he was about to be rich but—isn’t luck always like this?—he got lost himself during a storm. He was found, of course, and told of the iron door, which he was never able to find again.

Thomas J. McDevitt, MD, tells this and many other entertaining stories in his book, Idaho’s Malad Valley, a History . He even reveals the name of the boy, who grew to be a man, then an old man who never tired of telling it. He was known for telling some tall tales as well, but this one was surely true.

Now, that big hunk of iron shouldn’t be so difficult to find today with metal detecting technology constantly improving, and there is no shortage of people willing to try.

But, before you start packing for a trip to Samaria, you might ask yourself this question: Why would anyone go to the trouble of installing a heavy iron door in a cave to hide his loot? Simply hiding the gold in the cave would seem better than putting in a door that all but said, “Break this lock, for behind this door is something of value.”

I should also note that there’s a fair chance you might run into an IRON DOOR AT THE MOUTH OF A CAVE in Idaho. Look closely there’s probably a sign on it that warns it is dangerous to enter unless you are an experienced spelunker. Also, it’s more likely to be a gate than a door, with plenty of room to let bats fly out at night and discover their own treasure.

Tempting, perhaps, but you're more likely to find bats behind this iron door that gold.

Tempting, perhaps, but you're more likely to find bats behind this iron door that gold.

Published on August 23, 2019 04:00

August 22, 2019

Foreboding Headlines

As I search through back issues of Idaho papers looking for something of interest for this series, I sometimes get an uneasy sense of foreboding. From my vantage point, decades hence, I often know what is about to happen as I skim stories leading up to a date. Such was the case as I followed the campaign for mayor of Boise in the 1927 newspapers. The Idaho Statesman headline on Wednesday morning, April 6, 1927, read, “LEMP OVERWHELMS EAGLESON FOR MAYOR THREE TO ONE.”

It was the headline of May 2nd I was looking for: “HERBERT LEMP INJURED DURING POLO MATCH.” Lemp was the captain of the Boise polo team. In the first practice game of the season, he was riding the ball toward the goal in the fourth chukker when his horse, Craven, stumbled. That sent the mayor-elect head-first into the dirt. The first report of his condition said that he was resting comfortably at St. Lukes and that friends were confident he would be able to attend his inauguration the next day.

Alas, no. The headline on May 7th read, “MAYOR H.F. LEMP DIES OF INJURIES SUFFERED IN FALL.” The story went on: “Herbert Frederick Lemp, mayor of Boise, died Friday morning at 7 o’clock, in St. Luke’s hospital.

“The fractious caprice of a half-tamed polo pony, which hurled the city’s mayor to the ground during a practice game last Sunday afternoon inflicted the injury which took his life.

“The death was announced to Boise citizens by the tolling of the Central fire state bell, which continued at 20-second intervals for an hour, and by flags flying at half-staff.”

Though he never got to serve Herbert, was not the first Lemp elected mayor of Boise. His father, John, turned a teacup full of Idaho City gold dust into a fortune through investments in brewing and real estate, making him the wealthiest man in Ada County. John Lemp served as mayor of Boise for a year, 1875-76.

A post in History of Boise 1863-1963 by Bob Hartman brought this story to my attention. Thanks, Bob. He also let me use the photo of Herbert Lemp on his horse, Scrambled Eggs, on the steps of the capitol.

It was the headline of May 2nd I was looking for: “HERBERT LEMP INJURED DURING POLO MATCH.” Lemp was the captain of the Boise polo team. In the first practice game of the season, he was riding the ball toward the goal in the fourth chukker when his horse, Craven, stumbled. That sent the mayor-elect head-first into the dirt. The first report of his condition said that he was resting comfortably at St. Lukes and that friends were confident he would be able to attend his inauguration the next day.

Alas, no. The headline on May 7th read, “MAYOR H.F. LEMP DIES OF INJURIES SUFFERED IN FALL.” The story went on: “Herbert Frederick Lemp, mayor of Boise, died Friday morning at 7 o’clock, in St. Luke’s hospital.

“The fractious caprice of a half-tamed polo pony, which hurled the city’s mayor to the ground during a practice game last Sunday afternoon inflicted the injury which took his life.

“The death was announced to Boise citizens by the tolling of the Central fire state bell, which continued at 20-second intervals for an hour, and by flags flying at half-staff.”

Though he never got to serve Herbert, was not the first Lemp elected mayor of Boise. His father, John, turned a teacup full of Idaho City gold dust into a fortune through investments in brewing and real estate, making him the wealthiest man in Ada County. John Lemp served as mayor of Boise for a year, 1875-76.

A post in History of Boise 1863-1963 by Bob Hartman brought this story to my attention. Thanks, Bob. He also let me use the photo of Herbert Lemp on his horse, Scrambled Eggs, on the steps of the capitol.

Published on August 22, 2019 04:00

August 21, 2019

Repost: The Sampson Roads

This appeared last weekend as one of my columns in the Idaho Press. Since some were unable to access it on Monday when I provided a link, here's a repost of that column.

Have you ever found yourself saying, “Somebody should do something about that”? Charlie Sampson, who often went by C.B., had one of those moments back in 1914. Rather than just letting the thought drift out of his head as you and I would likely do, Sampson took on a little job himself. He began marking highways in Idaho so people wouldn’t get lost.

Starting in 1906, Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. His specialty was pianos. One of the ads for his pianos was a testimonial that read in part, “I play third grade music already, and my daddy only bought me my piano a little over a year ago.”

One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company. Oh, and you could stop by the store and pick up a free map. By the way, could we interest you in a piano?

It wasn’t uncommon in the early days of automobile roads in the U.S. for car clubs to take on the job of marking routes and adding mileage signs to various locations. Since state governments didn’t take on the responsibility at first, the clubs were free to mark roads in any way they wished and to install signs of their own invention. Things got confusing when two or more car clubs competed to be the markers of a road, since there wasn’t always agreement on which was the main road and which was just a muddy side road. Different colored markings denoted the work of different clubs. Nothing was standardized. It was a mess. For instance, the first stop sign didn’t pop up until 1915 in Detroit, according to an article by Ethen Trex in the December 2010 edition of Mental Floss. It was a simple square, white sign with black lettering that was more of a suggestion than a regulation.

Sampson got the jump on car clubs in Idaho and did such a good job that he “owned” the Sampson Trails. He even hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape, spending thousands of dollars on the project.

In the mid 1920s the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They would sometimes mark a parallel route and paint over Sampson’s markers. The highway men, pun intended, claimed Sampson defaced the landscape with his orange paint. He probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and giving him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Sampson eventually extended his work to five states, marking an astonishing 7,000 miles of road. Early highway maps often used the Sampson identifiers rather than state road names.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One of those people is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious, where I first learned about the Sampson Trails, is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history. The dot on the rock indicated by the sign in this picture doesn’t look like much, but those orange splashes of paint along with a complimentary highway map from Sampson Music of Boise were the best way to know where you were in the early days of driving in Idaho. The photo, which is courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department, depicts a 1916 Model T Ford, probably somewhere in the Treasure Valley.

The dot on the rock indicated by the sign in this picture doesn’t look like much, but those orange splashes of paint along with a complimentary highway map from Sampson Music of Boise were the best way to know where you were in the early days of driving in Idaho. The photo, which is courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department, depicts a 1916 Model T Ford, probably somewhere in the Treasure Valley.

Have you ever found yourself saying, “Somebody should do something about that”? Charlie Sampson, who often went by C.B., had one of those moments back in 1914. Rather than just letting the thought drift out of his head as you and I would likely do, Sampson took on a little job himself. He began marking highways in Idaho so people wouldn’t get lost.

Starting in 1906, Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. His specialty was pianos. One of the ads for his pianos was a testimonial that read in part, “I play third grade music already, and my daddy only bought me my piano a little over a year ago.”

One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company. Oh, and you could stop by the store and pick up a free map. By the way, could we interest you in a piano?

It wasn’t uncommon in the early days of automobile roads in the U.S. for car clubs to take on the job of marking routes and adding mileage signs to various locations. Since state governments didn’t take on the responsibility at first, the clubs were free to mark roads in any way they wished and to install signs of their own invention. Things got confusing when two or more car clubs competed to be the markers of a road, since there wasn’t always agreement on which was the main road and which was just a muddy side road. Different colored markings denoted the work of different clubs. Nothing was standardized. It was a mess. For instance, the first stop sign didn’t pop up until 1915 in Detroit, according to an article by Ethen Trex in the December 2010 edition of Mental Floss. It was a simple square, white sign with black lettering that was more of a suggestion than a regulation.

Sampson got the jump on car clubs in Idaho and did such a good job that he “owned” the Sampson Trails. He even hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape, spending thousands of dollars on the project.

In the mid 1920s the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They would sometimes mark a parallel route and paint over Sampson’s markers. The highway men, pun intended, claimed Sampson defaced the landscape with his orange paint. He probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and giving him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Sampson eventually extended his work to five states, marking an astonishing 7,000 miles of road. Early highway maps often used the Sampson identifiers rather than state road names.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One of those people is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious, where I first learned about the Sampson Trails, is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The dot on the rock indicated by the sign in this picture doesn’t look like much, but those orange splashes of paint along with a complimentary highway map from Sampson Music of Boise were the best way to know where you were in the early days of driving in Idaho. The photo, which is courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department, depicts a 1916 Model T Ford, probably somewhere in the Treasure Valley.

The dot on the rock indicated by the sign in this picture doesn’t look like much, but those orange splashes of paint along with a complimentary highway map from Sampson Music of Boise were the best way to know where you were in the early days of driving in Idaho. The photo, which is courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department, depicts a 1916 Model T Ford, probably somewhere in the Treasure Valley.

Published on August 21, 2019 04:00

August 20, 2019

Gretchen's Gold

Some of our more famous Idahoans weren’t born here. They chose Idaho, which simply indicates their good sense.

Gretchen Fraser was born in Tacoma, Washington. She fell in love with Idaho—and fell in love—in 1938 when she came to Sun Valley to compete in the Harriman Cup ski race. She met her future husband, Donald Fraser on the train traveling to Idaho. Donald had been a member of the 1936 US Olympic ski team. The two were married in 1939 and took up residence in Sun Valley. Both became members of the 1940 US Olympic ski team.

The 1940 games were canceled because of the war. It was 1948 before Gretchen got her chance to compete in the Olympics at age 29. She made the most of it, winning gold in the women’s slalom and silver in the combined event. She was the first American to win a gold medal in Olympic skiing.

Fraser continued to ski and promote the sport after her triumph. She made a couple of appearances in the movies as a stand-in skier for Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice” and that quintessential Sun Valley movie, “Sun Valley Serenade.” Fraser influenced future Olympians, mentoring Idaho medal winners Christin Cooper and Picabo Street, as well as Idahoan Muffy Davis, who won three gold medals in the Paralympics in 2012.

Gretchen Fraser was born in Tacoma, Washington. She fell in love with Idaho—and fell in love—in 1938 when she came to Sun Valley to compete in the Harriman Cup ski race. She met her future husband, Donald Fraser on the train traveling to Idaho. Donald had been a member of the 1936 US Olympic ski team. The two were married in 1939 and took up residence in Sun Valley. Both became members of the 1940 US Olympic ski team.

The 1940 games were canceled because of the war. It was 1948 before Gretchen got her chance to compete in the Olympics at age 29. She made the most of it, winning gold in the women’s slalom and silver in the combined event. She was the first American to win a gold medal in Olympic skiing.

Fraser continued to ski and promote the sport after her triumph. She made a couple of appearances in the movies as a stand-in skier for Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice” and that quintessential Sun Valley movie, “Sun Valley Serenade.” Fraser influenced future Olympians, mentoring Idaho medal winners Christin Cooper and Picabo Street, as well as Idahoan Muffy Davis, who won three gold medals in the Paralympics in 2012.

Published on August 20, 2019 04:00