Rick Just's Blog, page 192

July 19, 2019

The Owsley Bridge

Bridges are expensive and take time to build. That’s why ferries were often the first method of getting goods, animals, and vehicles across rivers in Idaho. The Owsley Ferry served river crossers for a few years in the early part of the 20th century. Just up-river from Salmon Falls and about 18 miles north of Buhl, the ferry began operation in 1903. Lea Owsley and his sons (he had 8 of them) ran it.

The Owsley Ferry wasn’t universally loved. Monopolies often aren’t. It probably wasn’t price gouging that caused the grumbling, though. Ferry rates were originally set by the Legislature. By the time the Owsley Ferry came along, the Idaho Public Utilities Commission was deciding how much the owners could charge.

In its later years, the ferry had a reputation for being dangerous. Its approaches were said to be unsafe and its equipment not well cared for. In 1918 Mrs. C.C. Leth drowned while using the Ferry. She and her husband plunged their car through the gates of the ferry into 20 feet of water. He got out. She didn’t. No mention of what caused the accident made the news.

For a time, the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) required the ferry to be “on call” during the night. Those wanting to cross would pull a string from one side of the river, which would ring a bell on the other side. In the December 2, 1919 edition of the Idaho Statesman it was reported that Don Lyman, of Twin Falls filed a complaint with the PUC because he and some of his friends spent an unproductive hour ceaselessly ringing the bell in near-zero weather without being able to raise anyone on the other side.

In any case, the Owsley Ferry would soon be replaced by the Owsley Bridge. It was one of the earliest projects of the Idaho Bureau of Highways, which started in 1919. One of their charges was to coordinate the construction of bridges in the state, largely taking over that task from the counties.

The Owsley Bridge was completed in 1921 at a cost of just over $127,000—about $1.8 million in today’s dollars. It was a cause for celebration. It was declared a holiday in Gooding and Twin Falls counties, which were joined by the bridge. More than 5,000 people showed up for the day of celebration as did some 800 cars. The day’s events included band concerts, horse and foot races, a baseball game, and free movies. Governor D.W. Davis was there to keynote the event. He couldn’t top the highlight of the day, a wedding ceremony held in the middle of the bridge on a platform built for the occasion.

The depth of the Snake River at the bridge site made it impossible to use a traditional truss system, which would have required building several supporting piers to hold up the 430-foot bridge. That seems somehow appropriate, because I am out of my depth here writing about engineering, so I’ll depend heavily on the application for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, written by Don Watts of the Idaho State Historic Preservation office in 1998.

Charles A. Kyle, the state bridge engineer, designed the “continuous cantilevered Warren through-truss” bridge. It is the only such bridge in the state. Watts noted in his application that the bridge was originally designed to span 429 feet, but the supporting piers were a foot further apart than they were supposed to be. Engineer Kyle found a way to lengthen the center joint and solve the problem.

Meanwhile, the Owsley Brothers, who were essentially put out of business by the new bridge, found it challenging to quit their ferry. The Public Utilities Commission refused to let them stop offering service until they appeared before the Commission to make the request in person, which they eventually did.

The Owsley Bridge, which did make the national register, can still be seen just off State Highway 30, 3.5 miles south of Hagerman.

Emma Davis and Jim Kriger of Okland travel on the Owsley Ferry, circa 1921. Courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Emma Davis and Jim Kriger of Okland travel on the Owsley Ferry, circa 1921. Courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

The Owsley Ferry wasn’t universally loved. Monopolies often aren’t. It probably wasn’t price gouging that caused the grumbling, though. Ferry rates were originally set by the Legislature. By the time the Owsley Ferry came along, the Idaho Public Utilities Commission was deciding how much the owners could charge.

In its later years, the ferry had a reputation for being dangerous. Its approaches were said to be unsafe and its equipment not well cared for. In 1918 Mrs. C.C. Leth drowned while using the Ferry. She and her husband plunged their car through the gates of the ferry into 20 feet of water. He got out. She didn’t. No mention of what caused the accident made the news.

For a time, the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) required the ferry to be “on call” during the night. Those wanting to cross would pull a string from one side of the river, which would ring a bell on the other side. In the December 2, 1919 edition of the Idaho Statesman it was reported that Don Lyman, of Twin Falls filed a complaint with the PUC because he and some of his friends spent an unproductive hour ceaselessly ringing the bell in near-zero weather without being able to raise anyone on the other side.

In any case, the Owsley Ferry would soon be replaced by the Owsley Bridge. It was one of the earliest projects of the Idaho Bureau of Highways, which started in 1919. One of their charges was to coordinate the construction of bridges in the state, largely taking over that task from the counties.

The Owsley Bridge was completed in 1921 at a cost of just over $127,000—about $1.8 million in today’s dollars. It was a cause for celebration. It was declared a holiday in Gooding and Twin Falls counties, which were joined by the bridge. More than 5,000 people showed up for the day of celebration as did some 800 cars. The day’s events included band concerts, horse and foot races, a baseball game, and free movies. Governor D.W. Davis was there to keynote the event. He couldn’t top the highlight of the day, a wedding ceremony held in the middle of the bridge on a platform built for the occasion.

The depth of the Snake River at the bridge site made it impossible to use a traditional truss system, which would have required building several supporting piers to hold up the 430-foot bridge. That seems somehow appropriate, because I am out of my depth here writing about engineering, so I’ll depend heavily on the application for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, written by Don Watts of the Idaho State Historic Preservation office in 1998.

Charles A. Kyle, the state bridge engineer, designed the “continuous cantilevered Warren through-truss” bridge. It is the only such bridge in the state. Watts noted in his application that the bridge was originally designed to span 429 feet, but the supporting piers were a foot further apart than they were supposed to be. Engineer Kyle found a way to lengthen the center joint and solve the problem.

Meanwhile, the Owsley Brothers, who were essentially put out of business by the new bridge, found it challenging to quit their ferry. The Public Utilities Commission refused to let them stop offering service until they appeared before the Commission to make the request in person, which they eventually did.

The Owsley Bridge, which did make the national register, can still be seen just off State Highway 30, 3.5 miles south of Hagerman.

Emma Davis and Jim Kriger of Okland travel on the Owsley Ferry, circa 1921. Courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Emma Davis and Jim Kriger of Okland travel on the Owsley Ferry, circa 1921. Courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Published on July 19, 2019 04:00

July 18, 2019

A Prediction of Power

Prognostication in print eventually tends to make the prognosticator look foolish. Witness the regular predictions about the fantastic future filled with flying cars, jet packs, and moving sidewalks common in the early Twentieth Century.

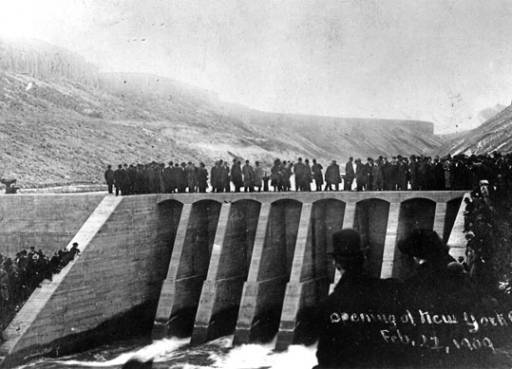

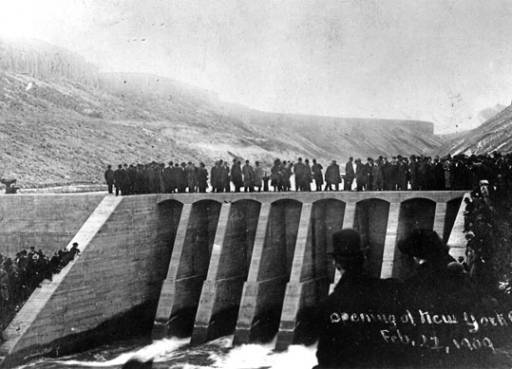

In 1909 one prognosticator at the Idaho Statesman got it right helped, perhaps, by his neglecting to establish a timeline for his predictions. The day following the dedication of Treasure Valley’s New York Canal on February, 22 1909, an article appeared titled “Power Behind the Dam.”

“Upon even the most thoughtless the real importance of the work, completion of which was yesterday celebrated will be forced to mind when thousands of acres of additional land is brought under cultivation, when Boise bounds to 150,000 population; when farms supplant great stretches of barren land and the swaddling clothes of towns in this part of the state are tossed into the rubbish heap in exchange for municipal togs.”

Boise’s population in 1909 was about 17,000, so a city of 150,000 probably seemed ludicrous. It would hit that mark in the early 1990s and today is closer to 250,000.

The progression from desert to farm to town to city was also correct. Eagle with a Hilton? Who’d have thought that in 1909 or even 1979?

Diversion Dam also supplied electricity for the valley for many years, as well as irrigation water for farmland that in more recent decades has grown into sprawling housing developments.

The photo of the dedication of New York Canal diversion is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive.

In 1909 one prognosticator at the Idaho Statesman got it right helped, perhaps, by his neglecting to establish a timeline for his predictions. The day following the dedication of Treasure Valley’s New York Canal on February, 22 1909, an article appeared titled “Power Behind the Dam.”

“Upon even the most thoughtless the real importance of the work, completion of which was yesterday celebrated will be forced to mind when thousands of acres of additional land is brought under cultivation, when Boise bounds to 150,000 population; when farms supplant great stretches of barren land and the swaddling clothes of towns in this part of the state are tossed into the rubbish heap in exchange for municipal togs.”

Boise’s population in 1909 was about 17,000, so a city of 150,000 probably seemed ludicrous. It would hit that mark in the early 1990s and today is closer to 250,000.

The progression from desert to farm to town to city was also correct. Eagle with a Hilton? Who’d have thought that in 1909 or even 1979?

Diversion Dam also supplied electricity for the valley for many years, as well as irrigation water for farmland that in more recent decades has grown into sprawling housing developments.

The photo of the dedication of New York Canal diversion is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive.

Published on July 18, 2019 04:00

July 17, 2019

Nixon in Boise

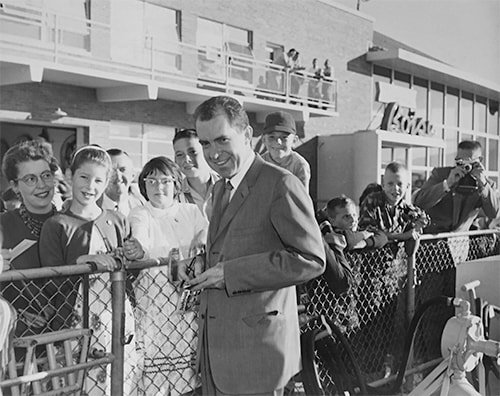

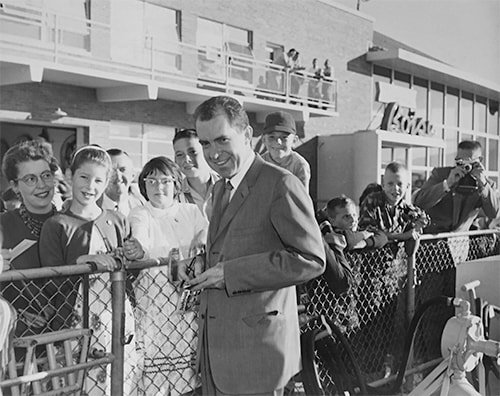

On September 13, 1960, the lead headline on the front page of the Idaho Statesman read, “Nixon to Make Major Address at BJC Tonight.” Yes, it was that Nixon. He was campaigning for president, running against John F. Kennedy. Nixon’s speech was about reclamation, power, and flood control. Idaho was selected for the location of the campaign speech because the state had much interest in the topics.

The speech was preceded by a bit of drama. The vice president’s airplane had one engine conk out shortly after it took off from Portland. The Boise Fire Department was on hand at the Boise Airport in case of trouble. Nixon shook hands with pilot Perry Thomas after the plane rolled to a stop and told him he had done “a darn good job.” Nixon insisted he wasn’t nervous about it, because there were three working engines on the plane and because it was the sixth time it had happened on a flight since he had become vice president. The plane made it to Boise about ten minutes early, even with one bum engine.

About 1,500 people came to see Richard Nixon at the airport, and about 5,000 lined the streets along the motorcade route to the Hotel Boise. That night’s speech was heard by about 4200 people, a near-capacity crowd at the Boise Junior College Auditorium.

Airplane troubles plagued another plane in the Nixon entourage when Nixon flew out on September 14. His plane was working fine, but about half of the 55 journalists accompanying the candidate had to wait four hours because their airplane had developed a leak in its hydraulic system. A substitute plane flew in from Seattle to pick them up and take them to Peoria, Illinois where Nixon was headed next.

The speech was preceded by a bit of drama. The vice president’s airplane had one engine conk out shortly after it took off from Portland. The Boise Fire Department was on hand at the Boise Airport in case of trouble. Nixon shook hands with pilot Perry Thomas after the plane rolled to a stop and told him he had done “a darn good job.” Nixon insisted he wasn’t nervous about it, because there were three working engines on the plane and because it was the sixth time it had happened on a flight since he had become vice president. The plane made it to Boise about ten minutes early, even with one bum engine.

About 1,500 people came to see Richard Nixon at the airport, and about 5,000 lined the streets along the motorcade route to the Hotel Boise. That night’s speech was heard by about 4200 people, a near-capacity crowd at the Boise Junior College Auditorium.

Airplane troubles plagued another plane in the Nixon entourage when Nixon flew out on September 14. His plane was working fine, but about half of the 55 journalists accompanying the candidate had to wait four hours because their airplane had developed a leak in its hydraulic system. A substitute plane flew in from Seattle to pick them up and take them to Peoria, Illinois where Nixon was headed next.

Published on July 17, 2019 04:00

July 16, 2019

The Horseshoe Town

Time for another in our series called Idaho Then and Now.

Utopian communities were common in 19th Century America. The still new country attracted people who envisioned a perfect society.

One such community was New Plymouth, Idaho. William E. Smythe founded the New Plymouth Society of Chicago with aim of building a planned community in Idaho’s Payette River Valley. Unlike some utopian community, this one wasn’t based on religious or moral principles but rather on planning and irrigation.

On April 17, 1985 the Idaho Daily Statesman carried a story that quoted Smythe. “Each colonist will purchase 20 acres of irrigated land and 20 shares of stock in the Plymouth company,” Smythe said. “He will also be entitled to an acre in the central area set apart for the village site if he will build a house upon it and make his home there.”

The town itself was platted out in a horseshoe shape with the open end of the horseshoe facing north toward the Payette River (Google Earth image below). Shareholders’ farms and orchards would all be within two or three miles of town.

The paper quoted Smythe, “There is to be nothing communistic about this New Plymouth. There is to be very little co-operation even, in the technical sense. The only property which is to be owned in common is the town hall, which is to be modeled after the Idaho building at the World’s Fair.” The fair had been held in Chicago in 1893. The community would have a library and an electric lighting plant.

The town was incorporated in February, 1896. It started out with a couple hundred residents, each with at least $1,000 in cash to their name, as was required by the colony. Today it’s population is about 1,500.

The shape of the town is about the only clue left about its origins. Citizens call it the “World’s Biggest Horseshoe.”

Planned communities today in Idaho tend to come in a couple of forms. The first type, not unlike New Plymouth, is built with an eye on planned amenities. Hidden Springs and Avimor near Boise and Eagle, respectively, are examples. The other type of planned community that we hear about involves a belief that some form of political or natural disaster is due. These are the survivalists who are looking for someplace to ride out the storm. The redoubt movement is an example.

Utopian communities were common in 19th Century America. The still new country attracted people who envisioned a perfect society.

One such community was New Plymouth, Idaho. William E. Smythe founded the New Plymouth Society of Chicago with aim of building a planned community in Idaho’s Payette River Valley. Unlike some utopian community, this one wasn’t based on religious or moral principles but rather on planning and irrigation.

On April 17, 1985 the Idaho Daily Statesman carried a story that quoted Smythe. “Each colonist will purchase 20 acres of irrigated land and 20 shares of stock in the Plymouth company,” Smythe said. “He will also be entitled to an acre in the central area set apart for the village site if he will build a house upon it and make his home there.”

The town itself was platted out in a horseshoe shape with the open end of the horseshoe facing north toward the Payette River (Google Earth image below). Shareholders’ farms and orchards would all be within two or three miles of town.

The paper quoted Smythe, “There is to be nothing communistic about this New Plymouth. There is to be very little co-operation even, in the technical sense. The only property which is to be owned in common is the town hall, which is to be modeled after the Idaho building at the World’s Fair.” The fair had been held in Chicago in 1893. The community would have a library and an electric lighting plant.

The town was incorporated in February, 1896. It started out with a couple hundred residents, each with at least $1,000 in cash to their name, as was required by the colony. Today it’s population is about 1,500.

The shape of the town is about the only clue left about its origins. Citizens call it the “World’s Biggest Horseshoe.”

Planned communities today in Idaho tend to come in a couple of forms. The first type, not unlike New Plymouth, is built with an eye on planned amenities. Hidden Springs and Avimor near Boise and Eagle, respectively, are examples. The other type of planned community that we hear about involves a belief that some form of political or natural disaster is due. These are the survivalists who are looking for someplace to ride out the storm. The redoubt movement is an example.

Published on July 16, 2019 04:00

July 15, 2019

An Idaho Hero

One hundred men received the Medal of Honor for heroism in World War I. The first of them to receive that medal was from Idaho. He was the first native-born Idahoan to receive that honor and was the first member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Days Saints to be so honored. He was the first U.S. Army private to receive the medal. And, he may have also been the first to return a Medal of Honor.

Private Thomas Neibaur was born in Sharon, Idaho, a tiny community north of Paris, and grew up in Sugar City. The actions for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor sound like those of a cinema super hero.

Wounded four times, Neibaur was captured by German troops after falling unconscious from his injuries. Awakening, he saw that the Germans had taken cover from heavy fire. He also saw that they had dropped his semi-automatic pistol on the ground nearby. He crawled to retrieve it. Enemy soldiers saw what he was doing and charged him with bayonets. He killed four of them, then captured the remaining 11 German soldiers, escorting them back across the American line.

General John J. Pershing presented Private Neibaur the Medal of Honor—often incorrectly called the Congressional Medal of Honor—at the request of President Woodrow Wilson.

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Neibaur held the French Croix de Guerre, the French Legion d’honneur, the French medaille militarie, the American distinguished service cross, the Italian La Croce al Merito di Guerra, and a Purple Heart.

Neibaur was treated as a hero, of course, when he returned to his home in Idaho. Governor D.W. Davis was on hand when Sugar City celebrated their favorite son on May 27, 1919. Some 10,000 people came out to honor him on “Neibaur Day,” proclaimed so in Idaho by Davis.

Neibaur, who would carry a German machine gun bullet in his hip until his dying day, lead a life that contained much trauma. His four bullet wounds led the list, joined by the pain of losing three sons to accidents, then having his arm mangled in a sugar factory accident.

Those pains were not all he endured. As the Great Depression was winding down, Neibaur found that the small pension he received along with his Medal of Honor and the $45-a-month paycheck he received for working as a clerk in the Works Progress Administration office in Boise were not enough to feed his large family. His income in 1938, including a $300 disability pension, was $900. Frustrated, he mailed his Medal of Honor to Senator William E. Borah with a note that said in part, that he “couldn’t eat it.”

Years earlier, Borah had proposed that Congress enact a measure promoting Neibaur to the rank of major and awarding him $2,200 in annual retirement pay. The bill failed that time, and again in 1939 when the Senate committee where the bill was introduced rejected the motion.

Three days after the story appeared in local papers Neibaur was given a job at the Idaho statehouse as a night security guard, helping his financial situation.

Thomas Neibaur died from tuberculosis in 1942 at the age of 44 at the Veteran’s Hospital in Walla Walla. His medals were returned to his wife, who in turn gave them to the Idaho State Historical Society.

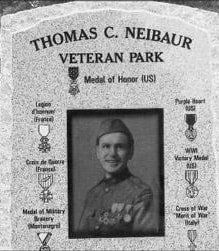

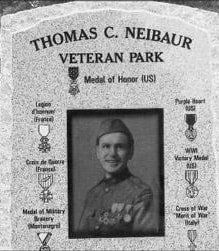

Thomas Neibaur wearing his medals. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical collection.

Thomas Neibaur wearing his medals. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical collection.  Neibaur memorial in Neibaur Park, Sugar City.

Neibaur memorial in Neibaur Park, Sugar City.

Private Thomas Neibaur was born in Sharon, Idaho, a tiny community north of Paris, and grew up in Sugar City. The actions for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor sound like those of a cinema super hero.

Wounded four times, Neibaur was captured by German troops after falling unconscious from his injuries. Awakening, he saw that the Germans had taken cover from heavy fire. He also saw that they had dropped his semi-automatic pistol on the ground nearby. He crawled to retrieve it. Enemy soldiers saw what he was doing and charged him with bayonets. He killed four of them, then captured the remaining 11 German soldiers, escorting them back across the American line.

General John J. Pershing presented Private Neibaur the Medal of Honor—often incorrectly called the Congressional Medal of Honor—at the request of President Woodrow Wilson.

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Neibaur held the French Croix de Guerre, the French Legion d’honneur, the French medaille militarie, the American distinguished service cross, the Italian La Croce al Merito di Guerra, and a Purple Heart.

Neibaur was treated as a hero, of course, when he returned to his home in Idaho. Governor D.W. Davis was on hand when Sugar City celebrated their favorite son on May 27, 1919. Some 10,000 people came out to honor him on “Neibaur Day,” proclaimed so in Idaho by Davis.

Neibaur, who would carry a German machine gun bullet in his hip until his dying day, lead a life that contained much trauma. His four bullet wounds led the list, joined by the pain of losing three sons to accidents, then having his arm mangled in a sugar factory accident.

Those pains were not all he endured. As the Great Depression was winding down, Neibaur found that the small pension he received along with his Medal of Honor and the $45-a-month paycheck he received for working as a clerk in the Works Progress Administration office in Boise were not enough to feed his large family. His income in 1938, including a $300 disability pension, was $900. Frustrated, he mailed his Medal of Honor to Senator William E. Borah with a note that said in part, that he “couldn’t eat it.”

Years earlier, Borah had proposed that Congress enact a measure promoting Neibaur to the rank of major and awarding him $2,200 in annual retirement pay. The bill failed that time, and again in 1939 when the Senate committee where the bill was introduced rejected the motion.

Three days after the story appeared in local papers Neibaur was given a job at the Idaho statehouse as a night security guard, helping his financial situation.

Thomas Neibaur died from tuberculosis in 1942 at the age of 44 at the Veteran’s Hospital in Walla Walla. His medals were returned to his wife, who in turn gave them to the Idaho State Historical Society.

Thomas Neibaur wearing his medals. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical collection.

Thomas Neibaur wearing his medals. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical collection.  Neibaur memorial in Neibaur Park, Sugar City.

Neibaur memorial in Neibaur Park, Sugar City.

Published on July 15, 2019 04:00

July 14, 2019

A Beautiful Insect

Did you know Idaho has a state insect? Yes, as do 44 other states. Many of them have TWO state insects, so stand by for legislation.

Idaho’s state insect is the monarch butterfly. Monarchs get around, so it may not surprise you that it is also the state insect of Vermont, Texas, Minnesota, Illinois, and Alabama.

Monarchs, or Danaus plexippus, if you want to get all Latin, rely on milkweed in their larval stage. As adult butterflies they feed on a variety of nectar-producing plants, accidentally spreading around pollen at the same time.

You probably know that monarchs migrate south for the winter. Western monarchs, those found in Idaho, typically over-winter in southern California, mostly around Pacific Grove. It’s not the same butterfly coming back in the spring that you waved farewell to in October. It takes three or four generations of butterflies to make a migration loop.

Many Idahoans can identify a monarch caterpillar (picture). Or can you? It surprised me to learn that there are a series of five stages of growth for a monarch in the larval form. The first caterpillar to hatch from those tiny butterfly eggs is translucent green, and less than a quarter of an inch long. It eats ferociously, then molts, revealing the beginnings of the white, black, and yellow markings we are familiar with. It eats again, and molts again, etc. until it reaches the fifth and final stage and its ultimate size, about 2 inches long.

Milkweed, which is unfortunately often considered a weed, is essential in the lifecycle of the monarch. So, if you can let them grow you’ll be helping Idaho’s official insect.

Idaho’s state insect is the monarch butterfly. Monarchs get around, so it may not surprise you that it is also the state insect of Vermont, Texas, Minnesota, Illinois, and Alabama.

Monarchs, or Danaus plexippus, if you want to get all Latin, rely on milkweed in their larval stage. As adult butterflies they feed on a variety of nectar-producing plants, accidentally spreading around pollen at the same time.

You probably know that monarchs migrate south for the winter. Western monarchs, those found in Idaho, typically over-winter in southern California, mostly around Pacific Grove. It’s not the same butterfly coming back in the spring that you waved farewell to in October. It takes three or four generations of butterflies to make a migration loop.

Many Idahoans can identify a monarch caterpillar (picture). Or can you? It surprised me to learn that there are a series of five stages of growth for a monarch in the larval form. The first caterpillar to hatch from those tiny butterfly eggs is translucent green, and less than a quarter of an inch long. It eats ferociously, then molts, revealing the beginnings of the white, black, and yellow markings we are familiar with. It eats again, and molts again, etc. until it reaches the fifth and final stage and its ultimate size, about 2 inches long.

Milkweed, which is unfortunately often considered a weed, is essential in the lifecycle of the monarch. So, if you can let them grow you’ll be helping Idaho’s official insect.

Published on July 14, 2019 04:00

July 13, 2019

The Lives of Ezra Meeker

To say that Ezra Meeker was a unique character in Western history is like saying Puyallup is a common name. Why that comparison? Meeker was the first mayor of Puyallup, Washington.

He was also one of the first to grow hops in the Puyallup Valley and soon earned the nickname “Hop King of the World.” He even wrote a book called Hop Culture in the United States. The “King” fell faster than he rose. At one point he was the wealthiest man in Washington Territory, but hop aphids and the panic of 1893 brought him down. He spent a few years selling dried vegetables in the Klondike, then returned to the town he platted from land he owned, Puyallup.

Meeker ran unsuccessfully for a couple of offices and started the Washington State Historical Society.

But this is a blog about Idaho, so you know there’s more to Meeker’s story.

Ezra Meeker had always been proud of his pioneer roots, especially the fact that he had come to Oregon Territory via the Oregon Trail in 1852. At age 71 (some sources say 75), he set out to do something he had long thought about. He wanted to travel the trail again, this time west to east. Again, he would travel in an ox-drawn wagon, not to venture to a new territory but to commemorate the trip thousands had made along the Oregon Trail. It was his intention to raise money and interest in placing monuments along the fast disappearing trail so that it would not be lost to history.

His slow journey east, in 1906, garnered more and more publicity as he plodded along. In Boise, Meeker told stories of the trail and convinced 1200 school children to donate their change to raise $100 for a granite monument with a brass plaque to be placed on the grounds of the capitol where it still stands today.

By the time Meeker and his schooner arrived in Montpelier, he had raised money along the way and erected 15 Oregon Trail monuments. The Montpelier Commercial Club began raising money to make it 16.

Eventually Meeker made it to his original jumping off point on the Oregon Trail, Eddyville, Iowa. He travelled on, selling postcards and other merchandise as he went to finance the journey, eventually ending up in New York City, where he took his ox team and wagon on a six-hour-drive the length of Manhattan. Later he would travel to Washington, DC, where he met with President Theodore Roosevelt. The president gave his support to the idea of establishing a cross-country highway, a dream of Meeker’s.

In 1910, Meeker took to the Oregon Trail again, this time not to raise money for monuments, but to locate and mark the fading trail. That trip ended in Denver when a flood damaged many of Meeker’s possessions.

In 1916 Meeker, now 85, headed out on the trail again, this time in a Pathfinder automobile. The company built a special body for the car, making it look a bit like an old covered wagon. Using the car gave him a chance to pitch the idea of a cross-country highway to more people, as well as telling the story of the Oregon Trail.

Meeker had one more trip in him. In 1924 he talked the Army into letting him fly across country with one of their pilots. He went again to Washington, DC to talk with the president about his favorite subjects. This time it was President Calvin Coolidge he met. That same year—Meeker was 95—he ran for the Washington House of Representatives, but was defeated in the Republican Primary by 35 votes.

Ezra Meeker (with beard) in Twin Falls on one of his trips. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Ezra Meeker (with beard) in Twin Falls on one of his trips. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

He was also one of the first to grow hops in the Puyallup Valley and soon earned the nickname “Hop King of the World.” He even wrote a book called Hop Culture in the United States. The “King” fell faster than he rose. At one point he was the wealthiest man in Washington Territory, but hop aphids and the panic of 1893 brought him down. He spent a few years selling dried vegetables in the Klondike, then returned to the town he platted from land he owned, Puyallup.

Meeker ran unsuccessfully for a couple of offices and started the Washington State Historical Society.

But this is a blog about Idaho, so you know there’s more to Meeker’s story.

Ezra Meeker had always been proud of his pioneer roots, especially the fact that he had come to Oregon Territory via the Oregon Trail in 1852. At age 71 (some sources say 75), he set out to do something he had long thought about. He wanted to travel the trail again, this time west to east. Again, he would travel in an ox-drawn wagon, not to venture to a new territory but to commemorate the trip thousands had made along the Oregon Trail. It was his intention to raise money and interest in placing monuments along the fast disappearing trail so that it would not be lost to history.

His slow journey east, in 1906, garnered more and more publicity as he plodded along. In Boise, Meeker told stories of the trail and convinced 1200 school children to donate their change to raise $100 for a granite monument with a brass plaque to be placed on the grounds of the capitol where it still stands today.

By the time Meeker and his schooner arrived in Montpelier, he had raised money along the way and erected 15 Oregon Trail monuments. The Montpelier Commercial Club began raising money to make it 16.

Eventually Meeker made it to his original jumping off point on the Oregon Trail, Eddyville, Iowa. He travelled on, selling postcards and other merchandise as he went to finance the journey, eventually ending up in New York City, where he took his ox team and wagon on a six-hour-drive the length of Manhattan. Later he would travel to Washington, DC, where he met with President Theodore Roosevelt. The president gave his support to the idea of establishing a cross-country highway, a dream of Meeker’s.

In 1910, Meeker took to the Oregon Trail again, this time not to raise money for monuments, but to locate and mark the fading trail. That trip ended in Denver when a flood damaged many of Meeker’s possessions.

In 1916 Meeker, now 85, headed out on the trail again, this time in a Pathfinder automobile. The company built a special body for the car, making it look a bit like an old covered wagon. Using the car gave him a chance to pitch the idea of a cross-country highway to more people, as well as telling the story of the Oregon Trail.

Meeker had one more trip in him. In 1924 he talked the Army into letting him fly across country with one of their pilots. He went again to Washington, DC to talk with the president about his favorite subjects. This time it was President Calvin Coolidge he met. That same year—Meeker was 95—he ran for the Washington House of Representatives, but was defeated in the Republican Primary by 35 votes.

Ezra Meeker (with beard) in Twin Falls on one of his trips. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Ezra Meeker (with beard) in Twin Falls on one of his trips. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Published on July 13, 2019 04:00

July 11, 2019

Boise's First Resident African American Woman

Elvina Moulton crossed the plains on the Oregon Trail with the family of a judge headed to California in 1867. She walked most of the way—sometimes barefoot—so by the time she got to Boise she was tired. She decided to stay. She got a job working in a laundry and saved enough money to buy a house next door to Boise Mayor—and later Idaho governor—James H. Hawley. Moulton also worked as a housekeeper, a seamstress, and a nurse. She was a quiet community member known affectionately as “Aunt Viny.” She helped found the First Presbyterian Church in Boise.

All of that might have gone unnoticed, but Moulton was a former slave, born in Kentucky in September 1837. She was probably Boise’s first resident African American woman.

When asked on her 88th birthday what her rules for long life were, (Idaho Statesman, September 17, 1916) she replied, “Well I never married, so nothing to worry about. I rested when my work was done and I went to church regularly. I guess this was the reason.”

Moulton regularly attended church and always put a silver dollar in the collection plate. Even so, she specified in her will that she didn’t “want to be buried from the church when I go. You see, I am the only colored member, and while everyone in the church has been good to me, I think it would be better to be buried from the undertaker’s, for there might be some feeling, you know.”

Moulton died at the age of 89 in 1917. She is buried in Morris Hill Cemetery. Elvina Moulton was honored in 2019 by the Daughters of the American Revolution with a historical marker and plaque at the Idaho Black History Museum.

All of that might have gone unnoticed, but Moulton was a former slave, born in Kentucky in September 1837. She was probably Boise’s first resident African American woman.

When asked on her 88th birthday what her rules for long life were, (Idaho Statesman, September 17, 1916) she replied, “Well I never married, so nothing to worry about. I rested when my work was done and I went to church regularly. I guess this was the reason.”

Moulton regularly attended church and always put a silver dollar in the collection plate. Even so, she specified in her will that she didn’t “want to be buried from the church when I go. You see, I am the only colored member, and while everyone in the church has been good to me, I think it would be better to be buried from the undertaker’s, for there might be some feeling, you know.”

Moulton died at the age of 89 in 1917. She is buried in Morris Hill Cemetery. Elvina Moulton was honored in 2019 by the Daughters of the American Revolution with a historical marker and plaque at the Idaho Black History Museum.

Published on July 11, 2019 04:00

July 10, 2019

The Taylor Topper

Once you’ve been a member of the U.S. Senate and a vice presidential candidate, what do you do with the rest of your life? The answer, for Glen Taylor, was to make hair pieces.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players. When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players. When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

Published on July 10, 2019 04:00

July 9, 2019

A Lunar Anniversary

So, where do you go if you want to give astronauts a crash course in lunar geology? Idaho, of course. It’s not called Craters of the Moon for nothing!

Just a few weeks after Neil Armstrong made that famous boot print on the moon, NASA astronauts Alan Shepard, Gene Cernan, Ed Mitchell, and Joe Engle took a trip to Idaho’s moon-like national monument to do a little exploring. All were highly educated men who had gone through rigorous training to become astronauts. Cernan had even been to the moon already, though he didn’t get to set foot there. He was the lunar module pilot for Apollo 10, which was a dress rehearsal swing around our natural satellite that did not include a landing.

Educated though the astronauts were, none of them were geologists. NASA wanted to give them a little hands-on training on rock gathering and how to identify various volcanic features. These atypical tourists only spent a day at Craters of the Moon, on August 22, 1969.

Shepard went on to command Apollo 14, becoming the fifth person to set foot on the moon. Ed Mitchell was stepper number six. Gene Cernan went to the moon a couple of times and spent more time there than anyone else. He was also the last man to walk on the moon when he commanded Apollo 17. Engle didn’t make it to the moon, but he did make it back to Craters of the Moon. He, Mitchell, and Cernan all came back to participate in the park’s 75th anniversary celebration in 1999. Alan Shepard had passed away from leukemia in 1998.

They’re celebrating again at Craters of the Moon this year on July 20th, the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. For more information about what they’re calling “Moonfest,” check this link.

By the way, the lunar astronauts did bring back some rocks; 842 pounds of them all told. They’re pricey little bits. A federal judge set their value at $50,800 per gram based on what it cost the federal government to go get them. That came up in a case where someone was trying to make some unauthorized sales of moon rocks.

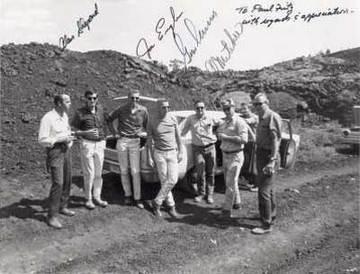

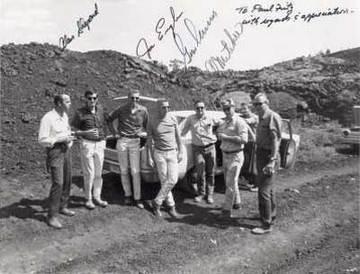

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Just a few weeks after Neil Armstrong made that famous boot print on the moon, NASA astronauts Alan Shepard, Gene Cernan, Ed Mitchell, and Joe Engle took a trip to Idaho’s moon-like national monument to do a little exploring. All were highly educated men who had gone through rigorous training to become astronauts. Cernan had even been to the moon already, though he didn’t get to set foot there. He was the lunar module pilot for Apollo 10, which was a dress rehearsal swing around our natural satellite that did not include a landing.

Educated though the astronauts were, none of them were geologists. NASA wanted to give them a little hands-on training on rock gathering and how to identify various volcanic features. These atypical tourists only spent a day at Craters of the Moon, on August 22, 1969.

Shepard went on to command Apollo 14, becoming the fifth person to set foot on the moon. Ed Mitchell was stepper number six. Gene Cernan went to the moon a couple of times and spent more time there than anyone else. He was also the last man to walk on the moon when he commanded Apollo 17. Engle didn’t make it to the moon, but he did make it back to Craters of the Moon. He, Mitchell, and Cernan all came back to participate in the park’s 75th anniversary celebration in 1999. Alan Shepard had passed away from leukemia in 1998.

They’re celebrating again at Craters of the Moon this year on July 20th, the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. For more information about what they’re calling “Moonfest,” check this link.

By the way, the lunar astronauts did bring back some rocks; 842 pounds of them all told. They’re pricey little bits. A federal judge set their value at $50,800 per gram based on what it cost the federal government to go get them. That came up in a case where someone was trying to make some unauthorized sales of moon rocks.

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Astronauts at Craters of the Moon National Monument, August 22, 1969. The signatures (from left to right) are: Alan Shepard, Joe Engle, Gene Cernan, and Ed Mitchell. NPS photo.

Published on July 09, 2019 04:00