Rick Just's Blog, page 195

June 18, 2019

Nuclear Nonsense

What if you had an airplane that could circle the globe for years? That question intrigued military planners in the 1940s so much that the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS), near Idaho Falls, set to work building one. It would run on atomic power, you see.

The atomic airplane would weigh 300 tons, stretch 205 feet long and measure 136 feet from wingtip to wingtip. Big, but smaller than a 747.

The plane was a joint project of the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission that began in in 1946. The goal was to come up with a practical airplane that could fly 15,000 miles without having to land.

They built a big earth-shielded hangar for the plane. The first photo shows construction and the completed hangar, which last I knew was being used for manufacturing tank armor.

That the plane’s hangar is being used for some other purpose is a clue about the plane itself. They did successfully test twin nuclear engines, but at 30 feet high they were a tad big for airplanes. Miniaturization might have been possible, eventually, if the project weren’t shelved in the early 60s. Technological problems, such shielding the pilots, weren’t what killed it. Fears that such a plane would eventually crash, making the accident site uninhabitable, brought it down before it ever went up, and before a prototype had been built.

Today, you can see the two Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment reactors, used in the effort to build an atomic-powered airplane. They sit in front of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I Atomic Museum at the site near Arco.

By the way the NRTS became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), then the Idaho National Lab (INL). It retains the latter designation today. Many people in eastern Idaho just call it The Site, rather than keep up with the acronyms.

Information about the nuclear plane comes largely from Susan Stacy’s book Proving the Principle, a History of the National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, 1949-1999 .

The atomic airplane would weigh 300 tons, stretch 205 feet long and measure 136 feet from wingtip to wingtip. Big, but smaller than a 747.

The plane was a joint project of the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission that began in in 1946. The goal was to come up with a practical airplane that could fly 15,000 miles without having to land.

They built a big earth-shielded hangar for the plane. The first photo shows construction and the completed hangar, which last I knew was being used for manufacturing tank armor.

That the plane’s hangar is being used for some other purpose is a clue about the plane itself. They did successfully test twin nuclear engines, but at 30 feet high they were a tad big for airplanes. Miniaturization might have been possible, eventually, if the project weren’t shelved in the early 60s. Technological problems, such shielding the pilots, weren’t what killed it. Fears that such a plane would eventually crash, making the accident site uninhabitable, brought it down before it ever went up, and before a prototype had been built.

Today, you can see the two Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment reactors, used in the effort to build an atomic-powered airplane. They sit in front of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I Atomic Museum at the site near Arco.

By the way the NRTS became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), then the Idaho National Lab (INL). It retains the latter designation today. Many people in eastern Idaho just call it The Site, rather than keep up with the acronyms.

Information about the nuclear plane comes largely from Susan Stacy’s book Proving the Principle, a History of the National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, 1949-1999 .

Published on June 18, 2019 04:00

June 17, 2019

Disappearing Derricks

Have you ever had the experience of driving down a highway you hadn’t been on for a while and getting an overwhelming feeling that something just wasn’t right? I’ve had that experience when I knew something was missing, something so ubiquitous that it had become an almost invisible background to the view. For me, it was most startling when I figured out the power lines that had paralleled the road had been buried. The roadside seemed suddenly naked.

A much slower disappearance has been going on for decades in Idaho. Something often taller than powerlines has been disappearing, one farm at a time until they’re all but gone. Hay derricks.

These crane-like contraptions were work savers for farmers when stacking hay, maybe for a hundred years. They stood like lonely sentinels in hay yards on the edge of fields all over Southern Idaho. They were often considered artifacts of Mormon folklife along with the ubiquitous plantings of Lombardy poplars as windbreaks.

Hay derricks were one of the few large pieces of farm equipment that was nearly always homemade. Most farmers didn’t bother sending away somewhere for plans. They just took a little trip to their neighbor’s hay yard and sketched out a plan for something like they saw there. That is, unless they could just borrow their neighbor’s derrick. They were movable, sometimes on skids and sometimes with attached wheels.

Today’s farmers are more likely to put up hay with a sophisticated bailer that churns out 1,000-pound round bales. There are not a lot of loose hay stacks still in existence, so the old derricks have been rotting away to nothing.

I could try to explain just how they work, but couldn’t do a better job than this video on a Library of Congress website.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows a hay derrick in operation at the State Hospital Farm in Blackfoot, circa 1930. The derrick is a particularly nice one, and probably custom made.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows a hay derrick in operation at the State Hospital Farm in Blackfoot, circa 1930. The derrick is a particularly nice one, and probably custom made.

A much slower disappearance has been going on for decades in Idaho. Something often taller than powerlines has been disappearing, one farm at a time until they’re all but gone. Hay derricks.

These crane-like contraptions were work savers for farmers when stacking hay, maybe for a hundred years. They stood like lonely sentinels in hay yards on the edge of fields all over Southern Idaho. They were often considered artifacts of Mormon folklife along with the ubiquitous plantings of Lombardy poplars as windbreaks.

Hay derricks were one of the few large pieces of farm equipment that was nearly always homemade. Most farmers didn’t bother sending away somewhere for plans. They just took a little trip to their neighbor’s hay yard and sketched out a plan for something like they saw there. That is, unless they could just borrow their neighbor’s derrick. They were movable, sometimes on skids and sometimes with attached wheels.

Today’s farmers are more likely to put up hay with a sophisticated bailer that churns out 1,000-pound round bales. There are not a lot of loose hay stacks still in existence, so the old derricks have been rotting away to nothing.

I could try to explain just how they work, but couldn’t do a better job than this video on a Library of Congress website.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows a hay derrick in operation at the State Hospital Farm in Blackfoot, circa 1930. The derrick is a particularly nice one, and probably custom made.

This photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows a hay derrick in operation at the State Hospital Farm in Blackfoot, circa 1930. The derrick is a particularly nice one, and probably custom made.

Published on June 17, 2019 04:00

June 16, 2019

Our First Territorial Governor and His Famous Relatives

William H. Wallace was Idaho’s first territorial governor and first congressional delegate. He had previously been Washington Territory’s delegate and territorial governor, so he had some experience under his belt. He also had a high-level friend, President Abraham Lincoln, whom he had known since the early 1850s.

Lincoln appointed Wallace governor while he was in Washington, DC representing Washington Territory. Wallace struck out for the new territory the fastest way possible, which was a 7,000-mile journey by sea and across the Isthmus of Panama. He arrived in Lewiston, the territorial capital, on July 23, 1863. He called the Territorial Legislature together in October, and one of their first decisions was to send Wallace back to Washington, DC, this time as the territorial delegate from Idaho.

He was serving there when on Monday, April 10, 1865, President Lincoln invited he and Mrs. Wallace to attend a performance at Ford Theatre the following Friday evening. For reasons unknown, Wallace declined the invitation. Lincoln was set to reappoint Wallace as territorial governor of Idaho, but that plan was dashed when the president was shot at the theatre. Wallace became one of Lincoln’s pallbearers.

I delight in telling the often-unimportant trivia associated with a story that sometimes makes it simmer if not sizzle, so will throw one in here that matters not a whit. Okay, this time, more than one:

1. William Wallace’s brother, David Wallace, served as governor of Indiana.

2. David Wallace’s son (and William Wallace’s nephew) Lew Wallace served as second in command of the court-martial of Lincoln assassination conspirators.

3. Lew Wallace did a sketch of those on trial and later did a well-known painting based on the sketch called The Conspirators.

4. Oh, and Lew Wallace wrote the novel Ben Hur .

The photo is courtesy of Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection

Lincoln appointed Wallace governor while he was in Washington, DC representing Washington Territory. Wallace struck out for the new territory the fastest way possible, which was a 7,000-mile journey by sea and across the Isthmus of Panama. He arrived in Lewiston, the territorial capital, on July 23, 1863. He called the Territorial Legislature together in October, and one of their first decisions was to send Wallace back to Washington, DC, this time as the territorial delegate from Idaho.

He was serving there when on Monday, April 10, 1865, President Lincoln invited he and Mrs. Wallace to attend a performance at Ford Theatre the following Friday evening. For reasons unknown, Wallace declined the invitation. Lincoln was set to reappoint Wallace as territorial governor of Idaho, but that plan was dashed when the president was shot at the theatre. Wallace became one of Lincoln’s pallbearers.

I delight in telling the often-unimportant trivia associated with a story that sometimes makes it simmer if not sizzle, so will throw one in here that matters not a whit. Okay, this time, more than one:

1. William Wallace’s brother, David Wallace, served as governor of Indiana.

2. David Wallace’s son (and William Wallace’s nephew) Lew Wallace served as second in command of the court-martial of Lincoln assassination conspirators.

3. Lew Wallace did a sketch of those on trial and later did a well-known painting based on the sketch called The Conspirators.

4. Oh, and Lew Wallace wrote the novel Ben Hur .

The photo is courtesy of Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection

Published on June 16, 2019 04:00

June 15, 2019

All Aboard for Grainville

The photo of this old railroad ticket was posted by Heather Heber Callahan recently on a closed group she operates. The purpose of the group is to help Heather get more information on photos from the Mike Fritz Collection.

This one was confusing because most people thought the ticket was surely for a train ride to Grangeville, Idaho, not Grainville, Idaho. Who’d ever heard of Grainville?

As it turns out, there was a Grainville, Idaho and that’s the destination this traveler was aiming for. Grainville is still around, though it’s an area nowadays, not a town. It’s in Fremont County, about a mile and a half west of Squirrel, another unincorporated spot. Maybe I better tell you it’s about 6 miles southeast of Ashton, just in case you don’t know where Squirrel is.

The holder of the ticket pictured would have been travelling on what was once the Oregon Shortline, a Union Pacific subsidiary so named because it was the shortest route from Wyoming to Oregon. The section of track that ran from Ashton to Tetonia was long ago abandoned. It became the Ashton to Tetonia Trail in 1994. The trail, which beckons hikers, bikers, and horseback riders in the summer, is used by snowmobilers in the winter. It is operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

In noodling around a bit for something interesting to say about the ticket, or the railway, or the trail, I found this tidbit about the Conant Creek Bridge, which is one of the old railroad bridges still in use on the trail. The bridge was originally installed on the Oregon Shortline in 1894 at American Falls where it crossed the Snake River. The 572-foot-long bridge was dismantled in 1911, and reconstructed at its present location in 1914.

Bitch Creek Trestle on the Ashton to Tetonia Trail is 640 long and about 150 feet above the water. It was built in 1924.

Bitch Creek Trestle on the Ashton to Tetonia Trail is 640 long and about 150 feet above the water. It was built in 1924.

This one was confusing because most people thought the ticket was surely for a train ride to Grangeville, Idaho, not Grainville, Idaho. Who’d ever heard of Grainville?

As it turns out, there was a Grainville, Idaho and that’s the destination this traveler was aiming for. Grainville is still around, though it’s an area nowadays, not a town. It’s in Fremont County, about a mile and a half west of Squirrel, another unincorporated spot. Maybe I better tell you it’s about 6 miles southeast of Ashton, just in case you don’t know where Squirrel is.

The holder of the ticket pictured would have been travelling on what was once the Oregon Shortline, a Union Pacific subsidiary so named because it was the shortest route from Wyoming to Oregon. The section of track that ran from Ashton to Tetonia was long ago abandoned. It became the Ashton to Tetonia Trail in 1994. The trail, which beckons hikers, bikers, and horseback riders in the summer, is used by snowmobilers in the winter. It is operated by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

In noodling around a bit for something interesting to say about the ticket, or the railway, or the trail, I found this tidbit about the Conant Creek Bridge, which is one of the old railroad bridges still in use on the trail. The bridge was originally installed on the Oregon Shortline in 1894 at American Falls where it crossed the Snake River. The 572-foot-long bridge was dismantled in 1911, and reconstructed at its present location in 1914.

Bitch Creek Trestle on the Ashton to Tetonia Trail is 640 long and about 150 feet above the water. It was built in 1924.

Bitch Creek Trestle on the Ashton to Tetonia Trail is 640 long and about 150 feet above the water. It was built in 1924.

Published on June 15, 2019 04:00

June 14, 2019

Pocatello, the Ship

This is the US Naval Frigate Pocatello, a patrol frigate that completed a dozen patrols west of Seattle during WWII. Three things are of interest about the otherwise prosaic history of the vessel. First, she was named after the City of Pocatello, Idaho. You may have surmised that. It wasn’t so clear in the AP report about her christening that appeared in the October 18, 1943, edition of the Idaho Statesman. That story had the boat being named for Chief Pocatello, not the city. Since the city was named after Chief Pocatello it is probably a moot point.

The Pocatello was launched from the Kaiser Shipyard in Richmond, California, which leads to the second point of interest. As the AP story reported, “Miss Thelma Dixey, 17, now of Oroville, Calif., sponsored the vessel. She was the granddaughter of Ralph Dixey, prominent Fort Hall Indian and great granddaughter of Chief Pocatello who headed the Bannock Tribe.

“Miss Dixey swung lustily with the champagne bottle as the ship slid into the waters of San Francisco Bay.

The final item of some interest is that the XO, or executive officer of the ship was Buddy Ebsen, who served aboard the Pocatello until she was decommissioned in 1946. Ebsen was a dancer and actor who appeared in many movies, including Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and became best known for his roles as Jed Clampett in The Beverly Hillbillies , and the title character in the TV series Barnaby Jones.

No word on whether or not he ever visited Pocatello.

The Pocatello was launched from the Kaiser Shipyard in Richmond, California, which leads to the second point of interest. As the AP story reported, “Miss Thelma Dixey, 17, now of Oroville, Calif., sponsored the vessel. She was the granddaughter of Ralph Dixey, prominent Fort Hall Indian and great granddaughter of Chief Pocatello who headed the Bannock Tribe.

“Miss Dixey swung lustily with the champagne bottle as the ship slid into the waters of San Francisco Bay.

The final item of some interest is that the XO, or executive officer of the ship was Buddy Ebsen, who served aboard the Pocatello until she was decommissioned in 1946. Ebsen was a dancer and actor who appeared in many movies, including Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and became best known for his roles as Jed Clampett in The Beverly Hillbillies , and the title character in the TV series Barnaby Jones.

No word on whether or not he ever visited Pocatello.

Published on June 14, 2019 04:00

June 13, 2019

Collector Plates

I write about Idaho license plates from time to time because they are ubiquitous and collectable at the same time. How collectable? Boise collector Dan P. Smith wrote the book on Idaho license plates. He says the rarest plates are the “pre-state” plates. That is, license plates issued by a city before the state got in the game. There are 19 of these plates known to exist from the cities of Boise, Emmett, Hailey, Lewiston, Nampa, Payette, Twin Falls, and Weiser.

The most sought-after Idaho plate is a 1913 passenger plate. That was the first year the state began issuing plates. Those can go for $3,000 or more.

Contrary to what you might think, the 1913 plates are not the rarest Idaho plates. There are about 40 of them in collector’s hands. There is only one Idaho motorcycle plate known to exist for the years 1917, 1920, 1922, 1929, 1934, and 1943.

Smith found one of his rarest plates on eBay for $30 a few years ago. It’s dray plate from 1940. A dray was essentially a beer truck. Smith thinks it might be the only dray plate from the state that still exists.

Even rarer than plates are windshield registration stickers. There are only three non-passenger stickers from 1943 known to exist. Windshields tend to get smashed on old junk cars.

This might be a good time to point out that finding a rare old Idaho plate isn’t like winning the lottery. Most of the collectable plates sell for under $100. The only Idaho dray plate known to exist.

The only Idaho dray plate known to exist.

The most sought-after Idaho plate is a 1913 passenger plate. That was the first year the state began issuing plates. Those can go for $3,000 or more.

Contrary to what you might think, the 1913 plates are not the rarest Idaho plates. There are about 40 of them in collector’s hands. There is only one Idaho motorcycle plate known to exist for the years 1917, 1920, 1922, 1929, 1934, and 1943.

Smith found one of his rarest plates on eBay for $30 a few years ago. It’s dray plate from 1940. A dray was essentially a beer truck. Smith thinks it might be the only dray plate from the state that still exists.

Even rarer than plates are windshield registration stickers. There are only three non-passenger stickers from 1943 known to exist. Windshields tend to get smashed on old junk cars.

This might be a good time to point out that finding a rare old Idaho plate isn’t like winning the lottery. Most of the collectable plates sell for under $100.

The only Idaho dray plate known to exist.

The only Idaho dray plate known to exist.

Published on June 13, 2019 04:00

June 12, 2019

Prisoners at Farragut

The top picture is of a group of troops at Farragut Naval Training Station getting ready to board “cattle cars” for some work assignment. Do you notice anything unusual about them?

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

Published on June 12, 2019 04:00

June 11, 2019

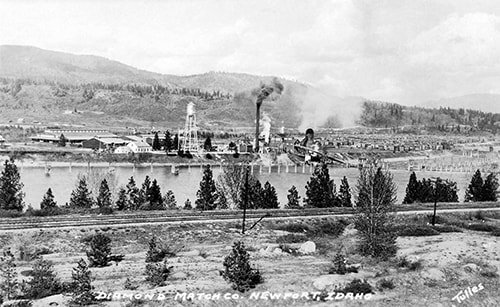

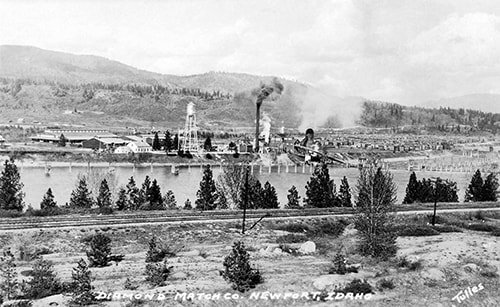

What's New(port) is Old(town) Again

You probably know about the Idaho and Washington “sister” cities of Lewiston and Clarkston, separated by the Snake River. But, do you know about the Idaho and Washington towns separated by… nothing?

Only the invisible state border separates Newport, Washington and Oldtown, Idaho. Both hug the Pend Oreille River about seven miles west of Priest River, Idaho. Newport got its name because it was selected as a landing site for the first steamboat on the Pend Oreille River. That was in 1890, when the landing and Newport were both in Idaho. A depot agent bought 40 acres in Washington and moved the Newport landing there. Since that became the Newport Landing, the residents of the old Newport in Idaho, began calling their little town Oldtown.

Newport, Washington was incorporated in 1903. Oldtown, Idaho became an officially incorporated town in 1947.

Oldtown, back when it was called (sigh) Newport, had a notorious resident who seemed to value money over morals. His name was William Vane. No one knew where he came from but he arrived in the 1890s. He acquired nearly the entire town of (then) Newport, Idaho in a business transaction that has been termed “questionable.” His life would be marked by a series of back and forth court filings on his way to becoming wealthy.

Vane had a relationship with the Great Northern Railroad that could be called contentious. He often profited from the railroad as a landowner, but also got into a fight with them over the location of a railroad track. He claimed the land on which it lay and underlined that claim by blowing up a railcar on the track with dynamite.

The Great Northern saw its profits leaking away on the line to Spokane because of a series of robberies. The Seattle Daily Times reported that a man arrested for selling stolen goods from one of those robberies had confessed he had purchased them from one William Vane. The prosecutor charged Vane with possession of stolen property. Despite that public charge, Vane decided to sue the Seattle paper for $250,000, charging that they had defamed his character.

Vane posted a $12,000 security bond in the possession of stolen property case, then disappeared. A man came forward to say that Vane had drowned in a boating accident. The Feds didn’t buy that. They did a little looking around and found William Vane posing as an Indian on the Kalispell Reservation. They arrested Vane and brought him back to the Pend Oreille County jail. He didn’t last long there. Jailers found him the next morning on death’s door, thanks to strychnine poisoning. Whether he died from his own hand or was murdered is still a subject of some debate.

William Vane is remembered as a scoundrel, but also a man who was once appointed as Justice of the Peace and the man who established the first hospital in town. The old one.

Image: Newport, Idaho was the site of a big Diamond Match Company Mill, which was the reason both water and railroad transportation was needed.

The Diamond Match Company mill at Newport, Idaho, back before it became Oldtown.

The Diamond Match Company mill at Newport, Idaho, back before it became Oldtown.

Only the invisible state border separates Newport, Washington and Oldtown, Idaho. Both hug the Pend Oreille River about seven miles west of Priest River, Idaho. Newport got its name because it was selected as a landing site for the first steamboat on the Pend Oreille River. That was in 1890, when the landing and Newport were both in Idaho. A depot agent bought 40 acres in Washington and moved the Newport landing there. Since that became the Newport Landing, the residents of the old Newport in Idaho, began calling their little town Oldtown.

Newport, Washington was incorporated in 1903. Oldtown, Idaho became an officially incorporated town in 1947.

Oldtown, back when it was called (sigh) Newport, had a notorious resident who seemed to value money over morals. His name was William Vane. No one knew where he came from but he arrived in the 1890s. He acquired nearly the entire town of (then) Newport, Idaho in a business transaction that has been termed “questionable.” His life would be marked by a series of back and forth court filings on his way to becoming wealthy.

Vane had a relationship with the Great Northern Railroad that could be called contentious. He often profited from the railroad as a landowner, but also got into a fight with them over the location of a railroad track. He claimed the land on which it lay and underlined that claim by blowing up a railcar on the track with dynamite.

The Great Northern saw its profits leaking away on the line to Spokane because of a series of robberies. The Seattle Daily Times reported that a man arrested for selling stolen goods from one of those robberies had confessed he had purchased them from one William Vane. The prosecutor charged Vane with possession of stolen property. Despite that public charge, Vane decided to sue the Seattle paper for $250,000, charging that they had defamed his character.

Vane posted a $12,000 security bond in the possession of stolen property case, then disappeared. A man came forward to say that Vane had drowned in a boating accident. The Feds didn’t buy that. They did a little looking around and found William Vane posing as an Indian on the Kalispell Reservation. They arrested Vane and brought him back to the Pend Oreille County jail. He didn’t last long there. Jailers found him the next morning on death’s door, thanks to strychnine poisoning. Whether he died from his own hand or was murdered is still a subject of some debate.

William Vane is remembered as a scoundrel, but also a man who was once appointed as Justice of the Peace and the man who established the first hospital in town. The old one.

Image: Newport, Idaho was the site of a big Diamond Match Company Mill, which was the reason both water and railroad transportation was needed.

The Diamond Match Company mill at Newport, Idaho, back before it became Oldtown.

The Diamond Match Company mill at Newport, Idaho, back before it became Oldtown.

Published on June 11, 2019 04:00

June 10, 2019

The Sampson Trails

Tourism professionals often lament that there are not better signs on our roads. Charlie Sampson thought the same thing back in 1914, and he did something about it.

Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company.

Sampson became such a believer in his markers that he hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape. He spent thousands of dollars on the project.

In 1933 the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They claimed it defaced the landscape. It probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and giving him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One of those people is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious, from which the story of Charlie Sampson was taken, is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The photo showing one of Sampson’s orange dots is from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Sampson ran the Sampson Music Company in Boise. One day, while making a delivery in the desert south of town, Charlie got lost. That annoyed him. He thought there should be signs along the roads so travelers could find their way. He took that suggestion to local officials. They ignored him. To their surprise, Sampson proved that he was not one to let a good idea die. He began to mark the roads around Boise himself.

Sampson carried a bucket of orange paint with him wherever he went, and painted signs on rocks, trees, barns, bridges, fences... just about anything that didn't move. The routes he marked became known locally as the Sampson Trails. Of course, many of the larger signs also included a few words about the Sampson Music Company.

Sampson became such a believer in his markers that he hired a three-man crew to keep the signs in shape. He spent thousands of dollars on the project.

In 1933 the Bureau of Highways decided to put a stop to Sampson's signing. They claimed it defaced the landscape. It probably did, but the Idaho Legislature didn't buy that argument. They passed a resolution commending Sampson for his efforts and giving him the right to continue marking the Sampson Trails.

Charlie Sampson died in 1935, leaving the task of guiding people along the roadways to others. One of those people is Cort Conley. His book, Idaho for the Curious, from which the story of Charlie Sampson was taken, is probably the best guide available for travelers interested in Idaho history.

The photo showing one of Sampson’s orange dots is from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on June 10, 2019 04:00

June 9, 2019

The Ice Man Cometh

In the early 1800s, a man named Fredric Tudor got the bright idea that one could cut ice from a lake in the winter and store it in an insulated shelter to make it available for sale in the summer. The Boston man eventually made his fortune with that idea, even sending ice by ship to the West Indies.

Another man from the Boston area started a business sawing and selling ice about the same time. He was an ice man in Cambridge in the early 1830s, and he was an iceman in Cambridge in 1836. In the intervening years he was decidedly not an iceman and decidedly not in Cambridge. He ran a store in Idaho, before Idaho was even a territory.

Nathaniel Wyeth had getting rich off the fur trade in mind. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company had started holding rendezvous, mostly in what would become Wyoming. A rendezvous was where trappers brought their season’s worth of furs to trade for supplies and sell for cash.

Wyeth got on the supply side of the equation. On April 28, 1834, he left Independence, Missouri with a loaded pack train of 250 horses, and 75 men headed for Ham’s Fork in the Green River country. A couple of naturalists and Methodist minister Jason Lee went along for the ride.

Wyeth must have felt pretty good about his chances of making a little coin, since he had a contract with the American Fur Company. What he didn’t count on was that the man who had been supplying the rendezvous since the beginning, William Sublette, had no intention of quitting the business. When Sublette found that Wyeth—and Sublette’s brother, Milton—were headed west with supplies, Bill Sublette threw together his own supply train and set out to beat the Wyeth train to the rendezvous.

If Wyeth had known he was in a race, he might have won it. As it was, Bill Sublette beat the Wyeth pack train to the rendezvous of 1834 and convinced Rocky Mountain representatives to let him supply the rendezvous, again, in spite of Wyeth’s contract.

Wyeth was livid. He wasn’t about to turn tail and head back east and sell everything for a loss, so he pushed on west and built a fort near where the Portneuf River dumps into the Snake. He named it Fort Hall after Henry Hall, one of his investors.

The Hudson Bay Company, a rival of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, saw the construction of Fort Hall as a threat and immediately put up their own supply post, Fort Boise, where the Boise River enters the Snake.

There was suddenly a glut of supplies for trappers. Seeing that fortune was not in his future at the fort, Wyeth sold out to the Hudson Bay Company in 1836 and went back to cutting ice in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Another man from the Boston area started a business sawing and selling ice about the same time. He was an ice man in Cambridge in the early 1830s, and he was an iceman in Cambridge in 1836. In the intervening years he was decidedly not an iceman and decidedly not in Cambridge. He ran a store in Idaho, before Idaho was even a territory.

Nathaniel Wyeth had getting rich off the fur trade in mind. The Rocky Mountain Fur Company had started holding rendezvous, mostly in what would become Wyoming. A rendezvous was where trappers brought their season’s worth of furs to trade for supplies and sell for cash.

Wyeth got on the supply side of the equation. On April 28, 1834, he left Independence, Missouri with a loaded pack train of 250 horses, and 75 men headed for Ham’s Fork in the Green River country. A couple of naturalists and Methodist minister Jason Lee went along for the ride.

Wyeth must have felt pretty good about his chances of making a little coin, since he had a contract with the American Fur Company. What he didn’t count on was that the man who had been supplying the rendezvous since the beginning, William Sublette, had no intention of quitting the business. When Sublette found that Wyeth—and Sublette’s brother, Milton—were headed west with supplies, Bill Sublette threw together his own supply train and set out to beat the Wyeth train to the rendezvous.

If Wyeth had known he was in a race, he might have won it. As it was, Bill Sublette beat the Wyeth pack train to the rendezvous of 1834 and convinced Rocky Mountain representatives to let him supply the rendezvous, again, in spite of Wyeth’s contract.

Wyeth was livid. He wasn’t about to turn tail and head back east and sell everything for a loss, so he pushed on west and built a fort near where the Portneuf River dumps into the Snake. He named it Fort Hall after Henry Hall, one of his investors.

The Hudson Bay Company, a rival of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, saw the construction of Fort Hall as a threat and immediately put up their own supply post, Fort Boise, where the Boise River enters the Snake.

There was suddenly a glut of supplies for trappers. Seeing that fortune was not in his future at the fort, Wyeth sold out to the Hudson Bay Company in 1836 and went back to cutting ice in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Published on June 09, 2019 04:00