Rick Just's Blog, page 193

July 8, 2019

The Fosbury Flop

Idaho has a claim on a sport-changing Olympian. Or, maybe he has a claim on Idaho. When Dick Fosbury won the gold medal in the 1968 Olympics he hailed from Oregon. But in 1977, he moved to Ketchum where he still lives. He is one of the owners of Galena Engineering. He ran for a seat in the Idaho Legislature in 2014 against incumbent Steve Miller, but lost that race.

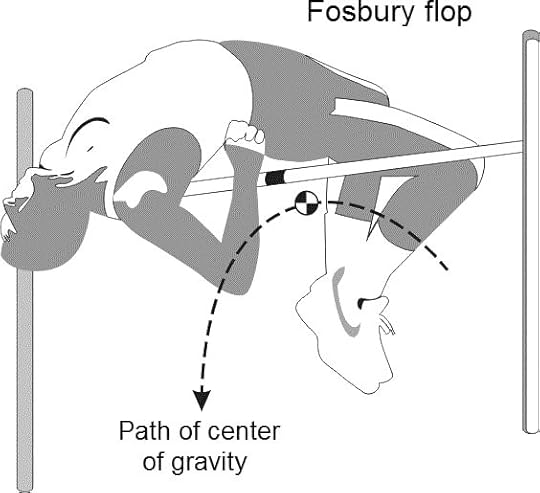

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips. The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Published on July 08, 2019 04:00

July 7, 2019

An Idaho Artist

Charles Ostner, who was born in Austria, immigrated to America to escape persecution in Germany. He had been involved in student uprisings there in 1848. He lived in California for about ten years working as a prospector. In 1860 the allure of gold brought him to the Florence Mining District in what would become Idaho. He found easy wealth a difficult thing to come by. On his way to Fabulous Florence, he got lost in the wilderness, spending nearly a month thrashing around. When found, Ostner was unconscious and emaciated. Life as a prospector had lost its allure.

Ostner bought an interest in a pack trail bridge in Garden Valley. The toll bridge was a reliable source of income. It gave him some time to pursue his art.

Horses were often the centerpiece of Ostner’s paintings (see Bear’s Attack below). In 1865 he felled a large pine at his Garden Valley homestead and set out to make a grand gesture for the recently formed Idaho Territory.

Ostner had some patience. It took him four years to carve the wooden statue of George Washington astride a horse that stands on the fourth floor of the Idaho statehouse today. Ostner modeled the statue in snow before committing it to pine. He studied the likeness of George Washington on a postage stamp to get the face right.

Ostner donated the statue to the Territory of Idaho in 1869. The Legislature granted him $2,500 for the work. It stood outside the statehouse on a pedestal for 65 years, before it was brought inside and gilded. For years the horse and rider were parked outside of the attorney general’s office, giving the secretary behind those glass doors an unobstructed view of the tail end of a golden horse. The statue was moved to the fourth floor during the 2007 renovation of the building.

Ostener died in 1913 and is buried in Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

Undated portrait of Charles Ostner, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Undated portrait of Charles Ostner, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.  Black and white copy of an oil painting of Ostner’s called Bear’s Attack, circa 1865. The original is in the ISHS archives. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Black and white copy of an oil painting of Ostner’s called Bear’s Attack, circa 1865. The original is in the ISHS archives. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.  The gilded statue of Washington astride his horse as it appears today on the fourth floor of the statehouse.

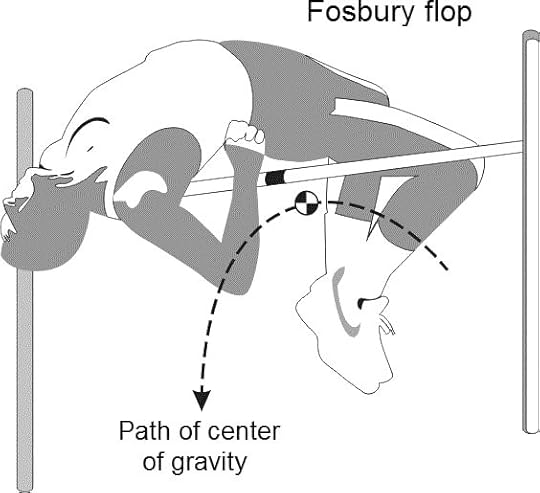

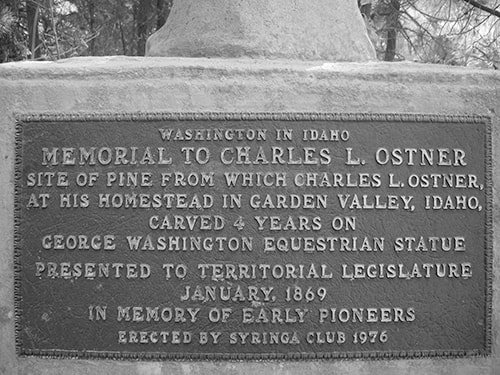

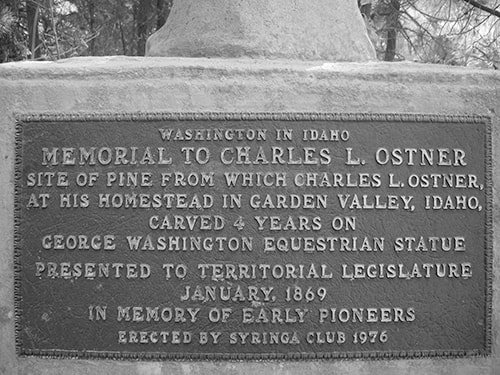

The gilded statue of Washington astride his horse as it appears today on the fourth floor of the statehouse.  Monument to Ostner erected on the site of his Garden Valley home in celebration of the country’s bicentennial in 1976.

Monument to Ostner erected on the site of his Garden Valley home in celebration of the country’s bicentennial in 1976.

A crowd gathered on February 21, 1915 for “Washington-Lincoln patriotic services” in front of the Washington statue carved by Charles Ostner. The woman in the center of the photo is Mrs. Charles Ostner. To the right of Mrs. Ostner is Mrs. R.C. Adelman (nee Julia Ostner). Mrs. J.D. Jones is to the left of Mrs. Ostner. The girl dressed in white and placing a wreath is Clare Elizabeth Jones, the Ostner’s granddaughter. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

A crowd gathered on February 21, 1915 for “Washington-Lincoln patriotic services” in front of the Washington statue carved by Charles Ostner. The woman in the center of the photo is Mrs. Charles Ostner. To the right of Mrs. Ostner is Mrs. R.C. Adelman (nee Julia Ostner). Mrs. J.D. Jones is to the left of Mrs. Ostner. The girl dressed in white and placing a wreath is Clare Elizabeth Jones, the Ostner’s granddaughter. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Ostner bought an interest in a pack trail bridge in Garden Valley. The toll bridge was a reliable source of income. It gave him some time to pursue his art.

Horses were often the centerpiece of Ostner’s paintings (see Bear’s Attack below). In 1865 he felled a large pine at his Garden Valley homestead and set out to make a grand gesture for the recently formed Idaho Territory.

Ostner had some patience. It took him four years to carve the wooden statue of George Washington astride a horse that stands on the fourth floor of the Idaho statehouse today. Ostner modeled the statue in snow before committing it to pine. He studied the likeness of George Washington on a postage stamp to get the face right.

Ostner donated the statue to the Territory of Idaho in 1869. The Legislature granted him $2,500 for the work. It stood outside the statehouse on a pedestal for 65 years, before it was brought inside and gilded. For years the horse and rider were parked outside of the attorney general’s office, giving the secretary behind those glass doors an unobstructed view of the tail end of a golden horse. The statue was moved to the fourth floor during the 2007 renovation of the building.

Ostener died in 1913 and is buried in Morris Hill Cemetery in Boise.

Undated portrait of Charles Ostner, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Undated portrait of Charles Ostner, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.  Black and white copy of an oil painting of Ostner’s called Bear’s Attack, circa 1865. The original is in the ISHS archives. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Black and white copy of an oil painting of Ostner’s called Bear’s Attack, circa 1865. The original is in the ISHS archives. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.  The gilded statue of Washington astride his horse as it appears today on the fourth floor of the statehouse.

The gilded statue of Washington astride his horse as it appears today on the fourth floor of the statehouse.  Monument to Ostner erected on the site of his Garden Valley home in celebration of the country’s bicentennial in 1976.

Monument to Ostner erected on the site of his Garden Valley home in celebration of the country’s bicentennial in 1976. A crowd gathered on February 21, 1915 for “Washington-Lincoln patriotic services” in front of the Washington statue carved by Charles Ostner. The woman in the center of the photo is Mrs. Charles Ostner. To the right of Mrs. Ostner is Mrs. R.C. Adelman (nee Julia Ostner). Mrs. J.D. Jones is to the left of Mrs. Ostner. The girl dressed in white and placing a wreath is Clare Elizabeth Jones, the Ostner’s granddaughter. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

A crowd gathered on February 21, 1915 for “Washington-Lincoln patriotic services” in front of the Washington statue carved by Charles Ostner. The woman in the center of the photo is Mrs. Charles Ostner. To the right of Mrs. Ostner is Mrs. R.C. Adelman (nee Julia Ostner). Mrs. J.D. Jones is to the left of Mrs. Ostner. The girl dressed in white and placing a wreath is Clare Elizabeth Jones, the Ostner’s granddaughter. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Published on July 07, 2019 04:00

July 6, 2019

POWs at Farragut

The top picture is of a group of troops at Farragut Naval Training Station getting ready to board “cattle cars” for some work assignment. Do you notice anything unusual about them?

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

Published on July 06, 2019 04:00

July 5, 2019

Helena's Peacock

Helena, Idaho became a full-fledged town in 1890, the year Idaho became a state. Yes, Helena, Idaho. Once known as Seven Devils (which is a clue as to its location), miners from Montana who were chasing their fortunes decided to call it Helena when they applied for a post office. Well, that’s one story. Another has it that the town was named for the first girl born in the camp.

Gold attracted most miners to the mountains of Idaho, but Helena was all about copper. Levi Allen discovered the mineral in the area in 1862. Three mines were worked there, the Helena, the White Monument, and the Peacock. Copper tends to be greenish in its natural state. The Peacock was so named because the ore there tended more toward blue.

Ore went out by wagon to Weiser until 1900 when the railroad reached Council. Then the wagons had a shorter route. A railroad was once planned to run from Helena to Weiser to pull out that ore. The price of copper killed that dream, and it was never finished. Soon, the town was. The post office closed in 1902. The town itself was abandoned in 1912.

There are reportedly still some remains of the town that may be of interest to ghost town buffs. It’s located about 10 miles north of Cuprum on Copper Creek, near the far end of the Kleinschmidt Grade. Pack a sandwich.

Gold attracted most miners to the mountains of Idaho, but Helena was all about copper. Levi Allen discovered the mineral in the area in 1862. Three mines were worked there, the Helena, the White Monument, and the Peacock. Copper tends to be greenish in its natural state. The Peacock was so named because the ore there tended more toward blue.

Ore went out by wagon to Weiser until 1900 when the railroad reached Council. Then the wagons had a shorter route. A railroad was once planned to run from Helena to Weiser to pull out that ore. The price of copper killed that dream, and it was never finished. Soon, the town was. The post office closed in 1902. The town itself was abandoned in 1912.

There are reportedly still some remains of the town that may be of interest to ghost town buffs. It’s located about 10 miles north of Cuprum on Copper Creek, near the far end of the Kleinschmidt Grade. Pack a sandwich.

Published on July 05, 2019 04:00

July 4, 2019

An Idaho Fourth

The Fourth of July has been celebrated in Idaho at least since July 4, 1861 when workers building the Mullan Road paused in their labors to celebrate. They marked the occasion by carving “M.R. 1861” on the trunk of a 250-year-old white pine on top of what would become to be known as Fourth of July Pass. “M.R.” could have stood for Mullan Road, as it is most often referred to today, but the initials meant Military Road. The tree where the men carved those initials stood until 1988 when it was split by a lightning strike. What was left of the trunk continued to mark the spot for several years, but continuing vandalism to the tree prompted authorities to cut the carving out of the trunk. You can see it today at the Museum of North Idaho in Coeur d’Alene.

Celebrations went on informally in the early days of the territory, often consisting of an Independence Day Ball, a picnic, street games, and perhaps a little drinking. It wasn’t until 1870 that Congress declared the Fourth of July a national holiday. In 1938 they went a step further and declared it a paid federal holiday.

Street games, by the way, were mainly races. They held sack races, foot races, and bicycle races. In 1886 they had something called “target practice” on the streets of Boise. Contestants were blind-folded and given a brace and bit—a hand operated drill. It is unclear all these years later exactly what they were supposed to do with it. There was a target 50 feet away and the winner was the one who came closest to the bullseye. One wonders if they were to throw the tool, or stumble forward blind-folded trying to find the target and drill a hole in it.

That same Fourth you might have won $2.50 for being the fastest to climb a greased pole. You could also win money by throwing a heavy hammer the farthest or by coming in first in the blindfold wheelbarrow race.

In 1890 the Fourth of July was going to be special. Word had made its way by telegraph that Congress had passed the statehood act for Idaho. The speculation was whether President Benjamin Harrison would sign it on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, or maybe even the 5th. As it turned out, the pen hit the paper on July 3rd, now known as Statehood Day in Idaho.

That 1890 parade featured a “Ship of State,” a float decked out as a large ship on wheels “gaily decorated with National colors, manned by a gallant crew of Boise youths.” It was followed by a float displaying the wealth of the new state, loaded down gold, silver, copper, and lead ores. Then came five huge saw logs pulled by powerful horses. The Coffin Brothers had a tin shop on wheels “going full blast.”

Miss Carrie Mobley rode in a Car of Liberty to personify the Territory of Idaho. She had not yet heard that Idaho was a state. Governor Shoup brought her up on a stage and addressed her as the newly formed state and informed her of the great change that had occurred. He made this point by removing a sash draped on one of her shoulders that read “Idaho” and replacing it with on that said in larger letters, “State of Idaho.”

Enjoy the day however you’re going to celebrate it.

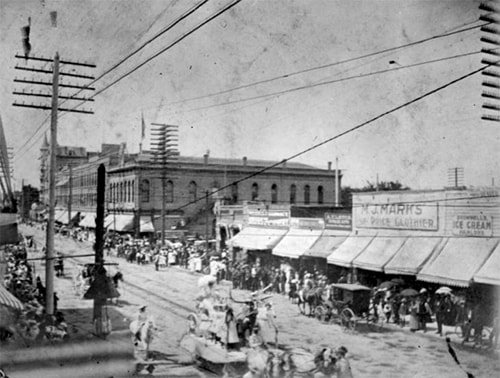

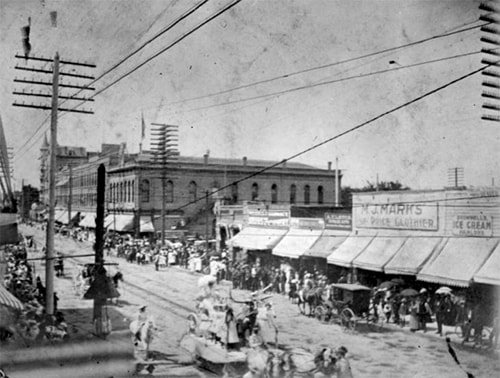

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Celebrations went on informally in the early days of the territory, often consisting of an Independence Day Ball, a picnic, street games, and perhaps a little drinking. It wasn’t until 1870 that Congress declared the Fourth of July a national holiday. In 1938 they went a step further and declared it a paid federal holiday.

Street games, by the way, were mainly races. They held sack races, foot races, and bicycle races. In 1886 they had something called “target practice” on the streets of Boise. Contestants were blind-folded and given a brace and bit—a hand operated drill. It is unclear all these years later exactly what they were supposed to do with it. There was a target 50 feet away and the winner was the one who came closest to the bullseye. One wonders if they were to throw the tool, or stumble forward blind-folded trying to find the target and drill a hole in it.

That same Fourth you might have won $2.50 for being the fastest to climb a greased pole. You could also win money by throwing a heavy hammer the farthest or by coming in first in the blindfold wheelbarrow race.

In 1890 the Fourth of July was going to be special. Word had made its way by telegraph that Congress had passed the statehood act for Idaho. The speculation was whether President Benjamin Harrison would sign it on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, or maybe even the 5th. As it turned out, the pen hit the paper on July 3rd, now known as Statehood Day in Idaho.

That 1890 parade featured a “Ship of State,” a float decked out as a large ship on wheels “gaily decorated with National colors, manned by a gallant crew of Boise youths.” It was followed by a float displaying the wealth of the new state, loaded down gold, silver, copper, and lead ores. Then came five huge saw logs pulled by powerful horses. The Coffin Brothers had a tin shop on wheels “going full blast.”

Miss Carrie Mobley rode in a Car of Liberty to personify the Territory of Idaho. She had not yet heard that Idaho was a state. Governor Shoup brought her up on a stage and addressed her as the newly formed state and informed her of the great change that had occurred. He made this point by removing a sash draped on one of her shoulders that read “Idaho” and replacing it with on that said in larger letters, “State of Idaho.”

Enjoy the day however you’re going to celebrate it.

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

A fuzzy Fourth of July picture from 1880, the Boise Parade, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 04, 2019 04:00

July 3, 2019

Happy Birthday, Idaho!

Today, July 3, is Statehood Day in Idaho. On this date in 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed the law admitting Idaho to the union as the 43rd state.

George Shoup, who had been appointed by Harris as territorial governor the year before, ran for governor of the new state and was elected in October of that year. He served as Idaho’s first governor for only a few weeks until the Idaho Legislature elected him senator.

Happy birthday, Idaho! You don’t look a day over 128.

George Shoup, who had been appointed by Harris as territorial governor the year before, ran for governor of the new state and was elected in October of that year. He served as Idaho’s first governor for only a few weeks until the Idaho Legislature elected him senator.

Happy birthday, Idaho! You don’t look a day over 128.

Published on July 03, 2019 04:00

July 2, 2019

Did a Jerk Found Pierce?

Randy Stapilus’ book

Speaking Ill of the Dead, Jerks in Idaho History

is an interesting read. He has a chapter on Elias Davidson Pierce. Pierce’s jerkiness, in Randy’s telling, comes from his complete disregard for both advice from authorities and reservation boundaries. I recommend you read the book to find out more.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Published on July 02, 2019 04:00

July 1, 2019

Fearless Farris the Crop Duster

I’m borrowing from my own book,

Fearless—Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk

for today’s post. Thanks to Farris Lind's son, Scott for providing some great photos from Farris’ crop dusting days.

A friend (of Farris Lind’s) from the Navy had heard about the pest control business. He called Farris and offered to sell him three Piper Cub airplanes for $2,500 each to use for spraying crops.

In the years after the war, many pilots had the idea of making a living through crop dusting. Some of them were in Idaho and already in the skies, but Farris Lind had an advantage over those men when it came to setting prices. He could get fuel at wholesale.

As it turned out, he could also get cut-rate airplanes. Farris was able to bend the ear of Senator Glenn Taylor who lined him up with some war surplus planes. Taylor was an entrepreneur himself and probably felt Lind was a kindred spirit. After serving one term in the U.S. Senate and failing to win reelection, Taylor invented and marketed a toupee called "The Taylor Topper," buying cheap ads in men's magazines all over the country. The "Toppers" were a success, and the company is still in business today.

Lind was also buying ads in the local paper for his new crop-dusting service. He bought enough that the Twin Falls Times-News didn't mind giving him a little free publicity. The paper ran an article that said in part, "Farris Lind… recently discharged Navy flier, will operate an aerial dusting service for Magic Valley farmers this season. He will maintain headquarters in Twin Falls for his fleet of six new planes that have been ordered." They also ran a picture of the smiling young pilot.

Finding pilots to fly his planes wasn't difficult for Lind. He knew many of them from his days as a Navy trainer. The pilots coming out of the war were mostly young men, some with more skill than judgment. It did not escape the notice of pilots that people often pulled off the country roads to watch them swoop down over the fields. It was like a free air show.

Some of the young men couldn't resist showing off. Benny Buchanan was an excellent pilot, and he loved proving it. On June 3, 1946, Buchanan had quite an audience. Several cars were parked on the road outside of Eden near the alfalfa field he was spraying. He even attracted a Greyhound bus full of onlookers. Rather than making a low-level run over the field and looping around for another run, Buchanan did hammerhead or stall turns at the end of each run. In a hammerhead, a pilot heads straight up into the air until the plane stalls, then jerks the rudder to bring the plane around 180 degrees, straight down. The dramatic maneuver at the end of each run and the beginning of the next had the crowd entranced until Benny lost control and slammed into a canal. He might have drowned if the impact had not killed him.

Less than a week later another of Lind’s pilots, Rudolph Klunt of Nampa, caught a wing on a turn and crashed into a field seven miles south of Twin Falls. He was not badly injured.

In 1948, a string of crashes culminated in the death of another crop-duster, Charles Gallaher, 39, of Coeur d'Alene. His plane nosed into the ground northwest of Jerome. Earl Allen, another Fearless Farris crop duster, crashed two planes in the same 10-day period as the Gallaher crash. He was not badly injured in either incident. Allen said he was "through with crop-dusting flights" after the second crash.

In three years, the pilots crashed seven of the company's 12 planes, and two pilots were dead. By 1949 there were a lot of people getting into the crop-dusting business; legal expenses were mounting up. It was time to get out. Lind sold

his fleet of airplanes to a company in California and closed up shop. He was done with crop dusting, but not with flying. He took a Staggerwing Beechcraft as partial payment for his fleet. The enclosed biplane became his personal conveyance.

Farris Lind clowning around with a damaged crop duster. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

Farris Lind clowning around with a damaged crop duster. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.  The crop dusting office at the Twin Falls Airport. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

The crop dusting office at the Twin Falls Airport. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.  One of Lind's earliest planes, a Piper Cub he purchased from a friend. That might be Charlie Reeder laying down the chemicals. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

One of Lind's earliest planes, a Piper Cub he purchased from a friend. That might be Charlie Reeder laying down the chemicals. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.  One of the Fearless Farris fleet of biplanes. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

One of the Fearless Farris fleet of biplanes. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

A friend (of Farris Lind’s) from the Navy had heard about the pest control business. He called Farris and offered to sell him three Piper Cub airplanes for $2,500 each to use for spraying crops.

In the years after the war, many pilots had the idea of making a living through crop dusting. Some of them were in Idaho and already in the skies, but Farris Lind had an advantage over those men when it came to setting prices. He could get fuel at wholesale.

As it turned out, he could also get cut-rate airplanes. Farris was able to bend the ear of Senator Glenn Taylor who lined him up with some war surplus planes. Taylor was an entrepreneur himself and probably felt Lind was a kindred spirit. After serving one term in the U.S. Senate and failing to win reelection, Taylor invented and marketed a toupee called "The Taylor Topper," buying cheap ads in men's magazines all over the country. The "Toppers" were a success, and the company is still in business today.

Lind was also buying ads in the local paper for his new crop-dusting service. He bought enough that the Twin Falls Times-News didn't mind giving him a little free publicity. The paper ran an article that said in part, "Farris Lind… recently discharged Navy flier, will operate an aerial dusting service for Magic Valley farmers this season. He will maintain headquarters in Twin Falls for his fleet of six new planes that have been ordered." They also ran a picture of the smiling young pilot.

Finding pilots to fly his planes wasn't difficult for Lind. He knew many of them from his days as a Navy trainer. The pilots coming out of the war were mostly young men, some with more skill than judgment. It did not escape the notice of pilots that people often pulled off the country roads to watch them swoop down over the fields. It was like a free air show.

Some of the young men couldn't resist showing off. Benny Buchanan was an excellent pilot, and he loved proving it. On June 3, 1946, Buchanan had quite an audience. Several cars were parked on the road outside of Eden near the alfalfa field he was spraying. He even attracted a Greyhound bus full of onlookers. Rather than making a low-level run over the field and looping around for another run, Buchanan did hammerhead or stall turns at the end of each run. In a hammerhead, a pilot heads straight up into the air until the plane stalls, then jerks the rudder to bring the plane around 180 degrees, straight down. The dramatic maneuver at the end of each run and the beginning of the next had the crowd entranced until Benny lost control and slammed into a canal. He might have drowned if the impact had not killed him.

Less than a week later another of Lind’s pilots, Rudolph Klunt of Nampa, caught a wing on a turn and crashed into a field seven miles south of Twin Falls. He was not badly injured.

In 1948, a string of crashes culminated in the death of another crop-duster, Charles Gallaher, 39, of Coeur d'Alene. His plane nosed into the ground northwest of Jerome. Earl Allen, another Fearless Farris crop duster, crashed two planes in the same 10-day period as the Gallaher crash. He was not badly injured in either incident. Allen said he was "through with crop-dusting flights" after the second crash.

In three years, the pilots crashed seven of the company's 12 planes, and two pilots were dead. By 1949 there were a lot of people getting into the crop-dusting business; legal expenses were mounting up. It was time to get out. Lind sold

his fleet of airplanes to a company in California and closed up shop. He was done with crop dusting, but not with flying. He took a Staggerwing Beechcraft as partial payment for his fleet. The enclosed biplane became his personal conveyance.

Farris Lind clowning around with a damaged crop duster. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

Farris Lind clowning around with a damaged crop duster. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.  The crop dusting office at the Twin Falls Airport. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

The crop dusting office at the Twin Falls Airport. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.  One of Lind's earliest planes, a Piper Cub he purchased from a friend. That might be Charlie Reeder laying down the chemicals. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

One of Lind's earliest planes, a Piper Cub he purchased from a friend. That might be Charlie Reeder laying down the chemicals. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.  One of the Fearless Farris fleet of biplanes. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

One of the Fearless Farris fleet of biplanes. Photo courtesy of Scott Lind.

Published on July 01, 2019 04:00

June 30, 2019

The DeSmet Fires

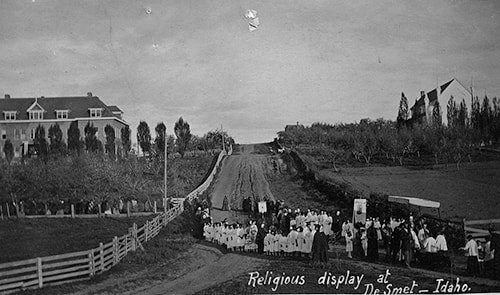

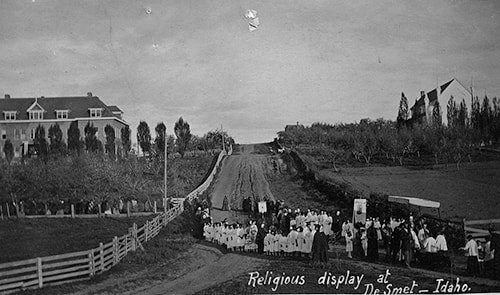

In this postcard image taken some time before 1939, the Mary Immaculate School in DeSmet is on the left, while the Gothic style Sacred Heart church is on the right. Both structures would end in flames, though 72 years apart.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate, but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate, but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

Published on June 30, 2019 04:00

June 29, 2019

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What was the name Idanha used for?

A. A hotel in Soda Springs

B. A hotel in Boise

C. Bottled water

D. A town in Oregon

E. All of the above

2). The first animal in the Boise Zoo was an escaped what?

A. Elk

B. Alligator

C. Chimpanzee

D. Pheasant

E. Tiger

3). What did Nathanial Wyeth do for a living before he founded Fort Hall?

A. Tailor

B. Soldier

C. Spy

D. Tinker

E. Iceman

4). What was Oldtown, Idaho called before it got that name?

A. Newport

B. Helena

C. Groveland

D. Esmerelda

E. Grove City

5) What atomic powered vehicle did they once plan to build at the AEC Site in eastern Idaho?

A. Submarine

B. Airplane

C. Rocket

D. Truck

E. Train Answers

Answers

1, E

2, C

3, E

4, A

5, B

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What was the name Idanha used for?

A. A hotel in Soda Springs

B. A hotel in Boise

C. Bottled water

D. A town in Oregon

E. All of the above

2). The first animal in the Boise Zoo was an escaped what?

A. Elk

B. Alligator

C. Chimpanzee

D. Pheasant

E. Tiger

3). What did Nathanial Wyeth do for a living before he founded Fort Hall?

A. Tailor

B. Soldier

C. Spy

D. Tinker

E. Iceman

4). What was Oldtown, Idaho called before it got that name?

A. Newport

B. Helena

C. Groveland

D. Esmerelda

E. Grove City

5) What atomic powered vehicle did they once plan to build at the AEC Site in eastern Idaho?

A. Submarine

B. Airplane

C. Rocket

D. Truck

E. Train

Answers

Answers1, E

2, C

3, E

4, A

5, B

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on June 29, 2019 04:00