Rick Just's Blog, page 190

August 8, 2019

Let Freedom... Tour

Have you seen the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia? Or, are you waiting for it to come to you?

Getting a visit from the bell is unlikely today, but it once travelled quite a lot to fairs and patriotic assemblages. On its most recent trip from Philadelphia it made it all the way to Idaho. That was over a hundred years ago.

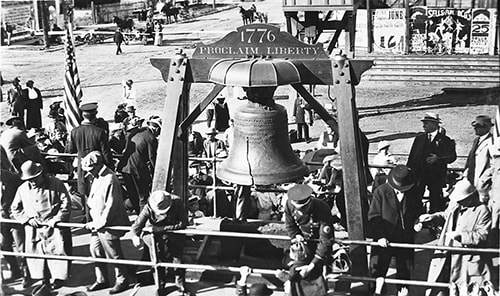

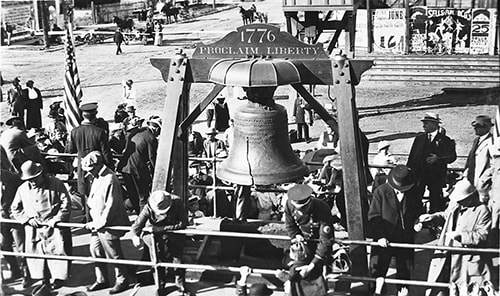

The Liberty Bell was the centerpiece of a bond drive to support World War I. Mounted on a railroad flatcar it toured the United States in 1915 on its way to the Panama-Pacific International exposition in San Francisco and back. By some estimates, half the people in the country turned out to see it.

The bell was on view in Boise from 7:15 to 8 am, July 13, 1915. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people came to see it. The arrival of the bell was front page news in the Meridian Times even though the bell didn’t make a stop in Meridian. It did slow down. About 8,000 people turned out in Caldwell for the 25-minute stop there, before it steamed away into Oregon for the final leg of its trip to San Francisco.

The bell was then, and remains today, a beloved US icon. Why, exactly? Partly because of its inscription, and partly because of a popular fiction that grew up around it.

The bell was cast in London in 1752, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, and inscribed with a quote from Leviticus, “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.”

The bell cracked right away when it was first rung in Philadelphia. It was twice recast to repair it.

A popular story had it that the bell rang out on July 4, 1776, announcing the Declaration of Independence. No such announcement was made that day, but historians agree it was probably one of many bells that rang in the city on July 8, when the announcement was made.

The original crack having been repaired, the bell cracked again—and remained so—sometime in the early 19th century.

As a symbol of liberty, it was a war bond star. Americans bought an average of $170 each in the Liberty Bell war bond drives. The Liberty Bell in Boise in 1915.

The Liberty Bell in Boise in 1915.

Getting a visit from the bell is unlikely today, but it once travelled quite a lot to fairs and patriotic assemblages. On its most recent trip from Philadelphia it made it all the way to Idaho. That was over a hundred years ago.

The Liberty Bell was the centerpiece of a bond drive to support World War I. Mounted on a railroad flatcar it toured the United States in 1915 on its way to the Panama-Pacific International exposition in San Francisco and back. By some estimates, half the people in the country turned out to see it.

The bell was on view in Boise from 7:15 to 8 am, July 13, 1915. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people came to see it. The arrival of the bell was front page news in the Meridian Times even though the bell didn’t make a stop in Meridian. It did slow down. About 8,000 people turned out in Caldwell for the 25-minute stop there, before it steamed away into Oregon for the final leg of its trip to San Francisco.

The bell was then, and remains today, a beloved US icon. Why, exactly? Partly because of its inscription, and partly because of a popular fiction that grew up around it.

The bell was cast in London in 1752, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, and inscribed with a quote from Leviticus, “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.”

The bell cracked right away when it was first rung in Philadelphia. It was twice recast to repair it.

A popular story had it that the bell rang out on July 4, 1776, announcing the Declaration of Independence. No such announcement was made that day, but historians agree it was probably one of many bells that rang in the city on July 8, when the announcement was made.

The original crack having been repaired, the bell cracked again—and remained so—sometime in the early 19th century.

As a symbol of liberty, it was a war bond star. Americans bought an average of $170 each in the Liberty Bell war bond drives.

The Liberty Bell in Boise in 1915.

The Liberty Bell in Boise in 1915.

Published on August 08, 2019 04:00

August 7, 2019

Going for a Record the Hard Way

First, don’t read this if you’re squeamish. Second, I know you’re still reading whether you’re squeamish or not because I’ve piqued your interest.

There are no rules in journalism about how a writer is supposed report on the discovery of a body. There are, however, conventions. Today, for instance, a reporter is not likely to give an elaborately detailed description of the recovery of the body, in respect for the relatives of the deceased if for no other reason.

Not so, apparently, in 1915. While researching a sensational kidnapping that took place that year in Bingham County, I noticed a story in The Idaho Republican headlined “Kleinschmidt’s Body is Found.” It caught my attention because the name reminded me of an Idaho place name, Kleinschmidt Grade in Hells Canyon. I read enough to see that there was no connection—just enough to “hook me in.” And, you don’t even know that’s a pun yet.

Although the story had a note about the funeral of William Kleinschmidt, it did not mention how he had died. From context, he drowned in the Snake River. The story mainly concerned itself with the remarkably short amount of time it took to find Kleinschmidt’s body, then went on to ponder about the length of time it had taken to find other bodies in the river over the preceding 30 years.

The body was discovered in a near record 53 hours. It was apparently more common to find a body after it had been in the water “nine days which marks a change in the weight of the body,” causing it to float.

“The means employed to find the body was a rope stretched across the stream, with floats to keep it from sinking in the stream and lines nine feet long dropping into the water with sinkers and hooks at the ends.” When anything heavy was encountered, the lines would quiver, and the men would pull up whatever the hook had snagged. This included a 50-pound lava rock that had a hole in it situated just right for the hook.

After describing exactly how and where the body was found in the river—face down, feet downstream, “the face only slightly marked by contact with moss and sand and gravel”—the reporter talked about the records that his readers were, no doubt, wondering about. “Vigils for lost bodies have usually covered a period varying from nine to 600 days. The longest period recorded was about 22 months in the case of George Neal, and the shortest was about one hour in the case of John Loveridge.”

In a mood for reminiscing, the reporter went through the details of the Loveridge drowning of 1890 or 1891, complete with a report on how the family of the man was doing all these years later. They had moved to Utah.

The paper noted that in 1912, one of Loveridge’s sons had come to Blackfoot searching for his father’s grave so he could put some flowers on it. In spite of the fact that Mr. Loveridge held the record for Fastest Recovery of a Body from the Snake River, which should surely have warranted a plaque, no one could find the man’s grave.

There are no rules in journalism about how a writer is supposed report on the discovery of a body. There are, however, conventions. Today, for instance, a reporter is not likely to give an elaborately detailed description of the recovery of the body, in respect for the relatives of the deceased if for no other reason.

Not so, apparently, in 1915. While researching a sensational kidnapping that took place that year in Bingham County, I noticed a story in The Idaho Republican headlined “Kleinschmidt’s Body is Found.” It caught my attention because the name reminded me of an Idaho place name, Kleinschmidt Grade in Hells Canyon. I read enough to see that there was no connection—just enough to “hook me in.” And, you don’t even know that’s a pun yet.

Although the story had a note about the funeral of William Kleinschmidt, it did not mention how he had died. From context, he drowned in the Snake River. The story mainly concerned itself with the remarkably short amount of time it took to find Kleinschmidt’s body, then went on to ponder about the length of time it had taken to find other bodies in the river over the preceding 30 years.

The body was discovered in a near record 53 hours. It was apparently more common to find a body after it had been in the water “nine days which marks a change in the weight of the body,” causing it to float.

“The means employed to find the body was a rope stretched across the stream, with floats to keep it from sinking in the stream and lines nine feet long dropping into the water with sinkers and hooks at the ends.” When anything heavy was encountered, the lines would quiver, and the men would pull up whatever the hook had snagged. This included a 50-pound lava rock that had a hole in it situated just right for the hook.

After describing exactly how and where the body was found in the river—face down, feet downstream, “the face only slightly marked by contact with moss and sand and gravel”—the reporter talked about the records that his readers were, no doubt, wondering about. “Vigils for lost bodies have usually covered a period varying from nine to 600 days. The longest period recorded was about 22 months in the case of George Neal, and the shortest was about one hour in the case of John Loveridge.”

In a mood for reminiscing, the reporter went through the details of the Loveridge drowning of 1890 or 1891, complete with a report on how the family of the man was doing all these years later. They had moved to Utah.

The paper noted that in 1912, one of Loveridge’s sons had come to Blackfoot searching for his father’s grave so he could put some flowers on it. In spite of the fact that Mr. Loveridge held the record for Fastest Recovery of a Body from the Snake River, which should surely have warranted a plaque, no one could find the man’s grave.

Published on August 07, 2019 04:00

August 6, 2019

The Territorial Capitol

As most Idahoan’s know, Lewiston was the first territorial capital. Even as territorial governor William H. Wallace arrived in Lewiston in July of 1863, the fate of the first capital was sealed, though no one knew it. I use that old saw about Lewiston’s fate being “sealed,” knowing full well that not a few of you will groan. Those not groaning, just wait a few more words.

Idaho Territory at its inception included what is now Montana. The size of the territory was going to make governing it from anywhere difficult. Fortunately, an influx of gold-seekers into mining camps across the Bitterroots led quickly to the formation of Montana Territory in May 1864.

Miners were also pouring into camps in the Boise Basin. A census of the territory in September 1863 showed a total population of 32,342, including 12,000 who would soon be in Montana. That left 20,342 in what would end up in the territory/state we know today. Boise County, which included the boomtowns of Idaho City and Atlanta, boasted 16,000 residents. With four times the residents in the south as in the north—the census missed Franklin and Paris for some reason—a seat of government in southern Idaho made sense.

It’s important to note that the Idaho Territorial Legislature had yet to designate any town as the seat of government at that point. In November, 1864, the second legislature assembled in Lewiston. Legislators from the northern part of the territory tried to dodge the issue of naming a capital by proposing to ask Congress to create a new Idaho Territory to include the panhandle and eastern Washington. Southern Idaho could do whatever it wanted. This would have left the southern part of the territory shaped something like Iowa (how would Easterners ever tell them apart??).

The southern legislators had enough clout to stop that idea, and they had enough votes to establish Boise as the permanent capital of Idaho Territory.

At the end of the second territorial legislature, Lewiston Lawyers fought the decision. They claimed the legislature had convened on the wrong day and thus many legislators weren’t really legislators.

Then Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, perhaps not having the stomach for this fight, simply left the territory. Quoting the Idaho State Historical Society Reference series on the subject, “Boise partisans tried to swipe the territorial seal and archives in order to remove them to Boise, Lewiston established an armed guard over the papers themselves. Both sides used loud language about each other, and there were petitions to Congress and hearings before a probate judge. His was not the proper court to hear the matter, but the proper court was incapacitated for reasons which embarrassed Lewiston. The territorial supreme court was not yet organized. The judges had not yet gotten together, and anyway the court was supposed to assemble in the capital and nobody knew where the capital was.”

During all this muddle, a new secretary of the territory, C. Dewitt Smith arrived in town. As the acting governor, in Governor Lyon’s absence, he called up troops from Ft. Lapwai and seized the territorial seal and took it to Boise. The territory organized its supreme court, and the court determined that the second territorial legislature, despite confusion about official dates, was legal and thus the capital was Boise. And thus my lame joke about Lewiston’s fate being sealed. Sorry Lewiston.

The photo is of the first territorial capitol. The building no longer exists, but history buffs and students from Lewiston High School’s senior construction class built a nice replica a few blocks away from the original site in 2013.

Idaho Territory at its inception included what is now Montana. The size of the territory was going to make governing it from anywhere difficult. Fortunately, an influx of gold-seekers into mining camps across the Bitterroots led quickly to the formation of Montana Territory in May 1864.

Miners were also pouring into camps in the Boise Basin. A census of the territory in September 1863 showed a total population of 32,342, including 12,000 who would soon be in Montana. That left 20,342 in what would end up in the territory/state we know today. Boise County, which included the boomtowns of Idaho City and Atlanta, boasted 16,000 residents. With four times the residents in the south as in the north—the census missed Franklin and Paris for some reason—a seat of government in southern Idaho made sense.

It’s important to note that the Idaho Territorial Legislature had yet to designate any town as the seat of government at that point. In November, 1864, the second legislature assembled in Lewiston. Legislators from the northern part of the territory tried to dodge the issue of naming a capital by proposing to ask Congress to create a new Idaho Territory to include the panhandle and eastern Washington. Southern Idaho could do whatever it wanted. This would have left the southern part of the territory shaped something like Iowa (how would Easterners ever tell them apart??).

The southern legislators had enough clout to stop that idea, and they had enough votes to establish Boise as the permanent capital of Idaho Territory.

At the end of the second territorial legislature, Lewiston Lawyers fought the decision. They claimed the legislature had convened on the wrong day and thus many legislators weren’t really legislators.

Then Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, perhaps not having the stomach for this fight, simply left the territory. Quoting the Idaho State Historical Society Reference series on the subject, “Boise partisans tried to swipe the territorial seal and archives in order to remove them to Boise, Lewiston established an armed guard over the papers themselves. Both sides used loud language about each other, and there were petitions to Congress and hearings before a probate judge. His was not the proper court to hear the matter, but the proper court was incapacitated for reasons which embarrassed Lewiston. The territorial supreme court was not yet organized. The judges had not yet gotten together, and anyway the court was supposed to assemble in the capital and nobody knew where the capital was.”

During all this muddle, a new secretary of the territory, C. Dewitt Smith arrived in town. As the acting governor, in Governor Lyon’s absence, he called up troops from Ft. Lapwai and seized the territorial seal and took it to Boise. The territory organized its supreme court, and the court determined that the second territorial legislature, despite confusion about official dates, was legal and thus the capital was Boise. And thus my lame joke about Lewiston’s fate being sealed. Sorry Lewiston.

The photo is of the first territorial capitol. The building no longer exists, but history buffs and students from Lewiston High School’s senior construction class built a nice replica a few blocks away from the original site in 2013.

Published on August 06, 2019 04:00

August 5, 2019

Meet William Orville Casey, a blind man with great sight

My latest column for Idaho Press.

Published on August 05, 2019 04:00

August 4, 2019

On the Basis of Sex

The 2018 movie,

On the Basis of Sex

, is about Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and how a famous court case about equal rights set the tone for her career. She wasn’t on the Supreme Court at that time. It was 1971. She was arguing for the rights of Sally Reed, a woman who was challenging an Idaho law.

Reed, from Boise, had been divorced from her husband for some time when the couple’s son committed suicide. The son left a small estate—less than $500 and a record collection. Sally Reed and her ex-husband each filed a petition with the probate court to administer that estate. Idaho law was very clear on how that should be decided. When both parties were equally qualified in such a matter, “the male must be preferred over the female.” The judge ruled in favor of Mr. Reed.

The sum was small, but the principle was large. Boise attorney Allen Derr agreed to represent Mrs. Reed. By the time the case worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, Idaho had changed its statutes eliminating preferences for males, but that didn’t make a decision less important.

While Derr argued the case, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the principle author of the brief that went before the Supreme Court. The decision was unanimous in favor of Sally Reed. It was a landmark case, the first where gender discrimination was declared unconstitutional because it denies equal protection.

Reed and the famous decision are memorialized at the site of her former home on the corner of W. Vista Ave. and Dorian St in Boise.

For a story about Allen Derr and the famous case, check the Boise Weekly.

Reed, from Boise, had been divorced from her husband for some time when the couple’s son committed suicide. The son left a small estate—less than $500 and a record collection. Sally Reed and her ex-husband each filed a petition with the probate court to administer that estate. Idaho law was very clear on how that should be decided. When both parties were equally qualified in such a matter, “the male must be preferred over the female.” The judge ruled in favor of Mr. Reed.

The sum was small, but the principle was large. Boise attorney Allen Derr agreed to represent Mrs. Reed. By the time the case worked its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, Idaho had changed its statutes eliminating preferences for males, but that didn’t make a decision less important.

While Derr argued the case, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the principle author of the brief that went before the Supreme Court. The decision was unanimous in favor of Sally Reed. It was a landmark case, the first where gender discrimination was declared unconstitutional because it denies equal protection.

Reed and the famous decision are memorialized at the site of her former home on the corner of W. Vista Ave. and Dorian St in Boise.

For a story about Allen Derr and the famous case, check the Boise Weekly.

Published on August 04, 2019 04:00

August 3, 2019

Building a State Parks System

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman. So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

I started out this short series by saying that the Railroad Ranch, which became Harriman State Park of Idaho, was crucial in the formation of Idaho’s state park system.

Gov. Robert E. Smylie (right in the picture) started trying to consolidate Idaho’s parks into a professional agency dedicated to their preservation and management in 1959. The Idaho Legislature was cool to the idea and turned the governor down on several occasions.

Then an opportunity came along that Smylie was quick to recognize. The governor had known E. Roland Harriman (left in the picture) for some time when the co-owner of the Railroad Ranch called.

Harriman and his brother Averell wanted to see the Railroad Ranch protected from development by donating it to the State of Idaho. Governor Smylie saw this as his chance to create a park system. Working mostly with Roland Harriman, the majority owner, Smylie inserted language in the gift deed that Idaho would be required to have a professionally trained park service in place before the transfer of the property was made.

Even with the donation of the Railroad Ranch as a tempting carrot, the 1963 legislature refused Smylie his state parks department, one more time. But they DID gladly accept the donation of the Railroad Ranch, which set things in motion so that the 1965 legislature finally gave Smylie his Idaho Department of Parks.

The donation was worth millions. The Idaho Department of Parks used that donation to match federal money in the Land and Water Conservation Fund to make other significant park improvements across the state.

So, in a way, Harriman State Park of Idaho, which didn’t open to the public until 1982, was the real beginning of the state park system in 1965.

By the way, the official name of the park is Harriman State Park of Idaho. That’s to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York. Same family. Same generosity.

I started out this short series by saying that the Railroad Ranch, which became Harriman State Park of Idaho, was crucial in the formation of Idaho’s state park system.

Gov. Robert E. Smylie (right in the picture) started trying to consolidate Idaho’s parks into a professional agency dedicated to their preservation and management in 1959. The Idaho Legislature was cool to the idea and turned the governor down on several occasions.

Then an opportunity came along that Smylie was quick to recognize. The governor had known E. Roland Harriman (left in the picture) for some time when the co-owner of the Railroad Ranch called.

Harriman and his brother Averell wanted to see the Railroad Ranch protected from development by donating it to the State of Idaho. Governor Smylie saw this as his chance to create a park system. Working mostly with Roland Harriman, the majority owner, Smylie inserted language in the gift deed that Idaho would be required to have a professionally trained park service in place before the transfer of the property was made.

Even with the donation of the Railroad Ranch as a tempting carrot, the 1963 legislature refused Smylie his state parks department, one more time. But they DID gladly accept the donation of the Railroad Ranch, which set things in motion so that the 1965 legislature finally gave Smylie his Idaho Department of Parks.

The donation was worth millions. The Idaho Department of Parks used that donation to match federal money in the Land and Water Conservation Fund to make other significant park improvements across the state.

So, in a way, Harriman State Park of Idaho, which didn’t open to the public until 1982, was the real beginning of the state park system in 1965.

By the way, the official name of the park is Harriman State Park of Idaho. That’s to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York. Same family. Same generosity.

Published on August 03, 2019 04:00

August 2, 2019

Famous Folks at Harriman

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman. So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

The Railroad Ranch, when it was owned by the Harrimans had many famous visitors. Probably none were better known than the Harrimans themselves.

Averell Harriman on the left is shown at the ranch in 1937. He served as US secretary of commerce under President Truman and later as governor of New York. He twice ran for president as a Democrat, in 1952 and 1956, defeated by Adlai Stevenson both times. He served as ambassador to the United Kingdom and to the Soviet Union. And, of course, he is remembered in Idaho as the developer of Sun Valley Ski Resort when he headed Union Pacific.

In the picture on the right is then Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Director Yvonne Ferrell with Pamela Harriman during a 1990s visit to the park. Pamela, in the hat, was the third wife of Averell. She was acquainted with many of the most famous figures of the 20th century, from Adolph Hitler, whom she met as a teenager, to Winston Churchill, who was her father-in-law during her first marriage. Pres. Bill Clinton appointed her ambassador to France in 1993.

The picture of Yvonne and Pamela happens to be one I took. Pamela brought Richard Helms with her on this visit. I don’t know why I don’t have a picture of him. Maybe as the former director of the CIA he just didn’t show up in photos.

The Railroad Ranch, when it was owned by the Harrimans had many famous visitors. Probably none were better known than the Harrimans themselves.

Averell Harriman on the left is shown at the ranch in 1937. He served as US secretary of commerce under President Truman and later as governor of New York. He twice ran for president as a Democrat, in 1952 and 1956, defeated by Adlai Stevenson both times. He served as ambassador to the United Kingdom and to the Soviet Union. And, of course, he is remembered in Idaho as the developer of Sun Valley Ski Resort when he headed Union Pacific.

In the picture on the right is then Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Director Yvonne Ferrell with Pamela Harriman during a 1990s visit to the park. Pamela, in the hat, was the third wife of Averell. She was acquainted with many of the most famous figures of the 20th century, from Adolph Hitler, whom she met as a teenager, to Winston Churchill, who was her father-in-law during her first marriage. Pres. Bill Clinton appointed her ambassador to France in 1993.

The picture of Yvonne and Pamela happens to be one I took. Pamela brought Richard Helms with her on this visit. I don’t know why I don’t have a picture of him. Maybe as the former director of the CIA he just didn’t show up in photos.

Published on August 02, 2019 04:00

August 1, 2019

Muir at the Railroad Ranch

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman. So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Many famous folks visited the Railroad Ranch over the years. We have some pictures of some of them, starting with John Muir. The picture on the left wasn’t taken at the ranch, though it looks like it could be. Muir was friends with E.H. Harriman, who was a big supporter of Muir in the Hetch Hetchy debate, which involved plans to build a dam in the area of Yosemite National Park. Muir was along on the famous 1899 Alaska Expedition, sponsored by E.H. Harriman. He visited the ranch in 1913. Some of his diary entries and sketches are featured on interpretive signs in the park today.

You probably haven’t heard of some of the famous visitors to the ranch, because fame is fleeting. On the right is Marriner S. Eccles. He was a well-known economist who served as chairman of the Federal Reserve under Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and was a proponent of New Deal programs. The Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC, is named after Eccles. He wasn’t just a visitor. He was one of the original investors in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company.

Tomorrow, two more contemporary ranch visitors you may have heard about in the news.

Many famous folks visited the Railroad Ranch over the years. We have some pictures of some of them, starting with John Muir. The picture on the left wasn’t taken at the ranch, though it looks like it could be. Muir was friends with E.H. Harriman, who was a big supporter of Muir in the Hetch Hetchy debate, which involved plans to build a dam in the area of Yosemite National Park. Muir was along on the famous 1899 Alaska Expedition, sponsored by E.H. Harriman. He visited the ranch in 1913. Some of his diary entries and sketches are featured on interpretive signs in the park today.

You probably haven’t heard of some of the famous visitors to the ranch, because fame is fleeting. On the right is Marriner S. Eccles. He was a well-known economist who served as chairman of the Federal Reserve under Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and was a proponent of New Deal programs. The Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC, is named after Eccles. He wasn’t just a visitor. He was one of the original investors in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company.

Tomorrow, two more contemporary ranch visitors you may have heard about in the news.

Published on August 01, 2019 04:00

July 31, 2019

Raising Livestock on the Railroad Ranch

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman. So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Raising cattle year-round at 6,200 feet above sea level calls for harvesting a lot of grass hay. In the picture on the left, five sickle bar horse-drawn mowers knock down the grass. The Harrimans bought an early steam tractor for use in the hay harvest but found that it did not work well because of the configuration of the fields and irrigation ditches, so they largely stuck with horse-drawn equipment.

There were several variations of the beaver slide, like the one pictured on the right used at the Railroad Ranch. The purpose of each was to use horsepower—later tractor power—to slide a load of hay up into the air and push it off onto a stack. The Railroad Ranch supplied beef to the Army during World War II. After the war, they stopped keeping cattle year-round, so they also stopped harvesting and stacking hay.

Cattle were not the only livestock raised on the Railroad Ranch. For a time, elk were commercially raised and shipped to markets in the east and sometimes for the Harriman’s table in New York. The ranch also tried raising bison commercially but found that they were very difficult to keep contained.

Bison were once native to what is called the Island Park area of eastern Idaho, north of Idaho Falls, so it made some sense to try raising them commercially, too. Masters at jumping over or smashing down fences, bison proved more trouble than they were worth.

Raising livestock was always just an excuse to keep a ranch for the Harrimans. They loved to just be at the place. Often they invited their famous friends to join them. We’ll meet a few of those folks tomorrow.

Raising cattle year-round at 6,200 feet above sea level calls for harvesting a lot of grass hay. In the picture on the left, five sickle bar horse-drawn mowers knock down the grass. The Harrimans bought an early steam tractor for use in the hay harvest but found that it did not work well because of the configuration of the fields and irrigation ditches, so they largely stuck with horse-drawn equipment.

There were several variations of the beaver slide, like the one pictured on the right used at the Railroad Ranch. The purpose of each was to use horsepower—later tractor power—to slide a load of hay up into the air and push it off onto a stack. The Railroad Ranch supplied beef to the Army during World War II. After the war, they stopped keeping cattle year-round, so they also stopped harvesting and stacking hay.

Cattle were not the only livestock raised on the Railroad Ranch. For a time, elk were commercially raised and shipped to markets in the east and sometimes for the Harriman’s table in New York. The ranch also tried raising bison commercially but found that they were very difficult to keep contained.

Bison were once native to what is called the Island Park area of eastern Idaho, north of Idaho Falls, so it made some sense to try raising them commercially, too. Masters at jumping over or smashing down fences, bison proved more trouble than they were worth.

Raising livestock was always just an excuse to keep a ranch for the Harrimans. They loved to just be at the place. Often they invited their famous friends to join them. We’ll meet a few of those folks tomorrow.

Published on July 31, 2019 04:00

July 30, 2019

Railroad Ranch Cattle Drives

I’m spending the week in Harriman State Park as director of the high school writing camp Writers at Harriman. So, I’m spending the week telling some stories about Harriman.

Yesterday, I mentioned that the Railroad Ranch was named that because several of the shareholders were railroad men, but that there never was a railroad at the ranch. There was one not far away, though.

Although Averell Harriman, well known in Idaho for creating the Sun Valley Resort when he ran Union Pacific Railroad, spent some time at the ranch, it was his brother Roland and wife Gladys who spent the most time there.

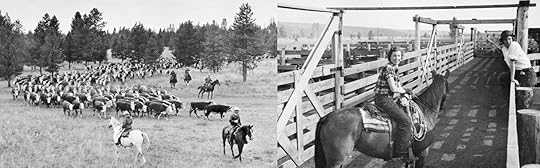

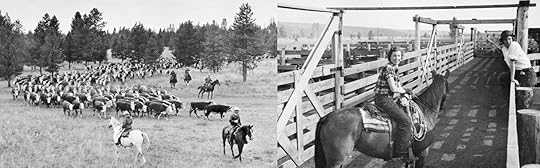

The picture on the left shows some of the Hereford cattle that were raised on the Railroad Ranch. In this shot from around 1960, Gladys Harriman is on her white horse, Geronimo, and E. Roland is on his horse, Buck. They were taking the herd a short distance to the Island Park siding to be shipped to market. In the picture on the right from about 1938, Elizabeth “Betty” Harriman is on her horse, Challis, helping move cattle at the nearby Island Park siding. Her sister Phyllis is on the fence. They were the daughters of Roland and Gladys Harriman.

Tomorrow, a little about what it took to raise cattle at 6,200 feet above sea level.

Yesterday, I mentioned that the Railroad Ranch was named that because several of the shareholders were railroad men, but that there never was a railroad at the ranch. There was one not far away, though.

Although Averell Harriman, well known in Idaho for creating the Sun Valley Resort when he ran Union Pacific Railroad, spent some time at the ranch, it was his brother Roland and wife Gladys who spent the most time there.

The picture on the left shows some of the Hereford cattle that were raised on the Railroad Ranch. In this shot from around 1960, Gladys Harriman is on her white horse, Geronimo, and E. Roland is on his horse, Buck. They were taking the herd a short distance to the Island Park siding to be shipped to market. In the picture on the right from about 1938, Elizabeth “Betty” Harriman is on her horse, Challis, helping move cattle at the nearby Island Park siding. Her sister Phyllis is on the fence. They were the daughters of Roland and Gladys Harriman.

Tomorrow, a little about what it took to raise cattle at 6,200 feet above sea level.

Published on July 30, 2019 04:00