Rick Just's Blog, page 198

May 19, 2019

An R-Rated Circus

Why that headline? When I've run this story in the past some people have found it disturbing because it reports on animal cruelty. I just wanted to warn you if you'd rather not read about that.

The first circus to appear in Idaho Territory put on a show August 6, 1864 in Boise. It was Don Rice’s circus, which the Idaho Statesman at the time noted “everyone has seen…in one part of the world or another.”

World renown was apparently the norm for circuses. The ad below is from the Idaho Statesman, June 8, 1865. Note that it is billed as the “most attractive performance ever presented to the world.” And only a buck!

Hyperbole aside, those circuses couldn’t match the spectacle that took place in Hailey as reported in the Daily Wood River Times on August 4, 1884. If you tend to get queasy about animal injury, skip this.

The headline about Cole’s Circus said, “Samson, the Huge Elephant, on the Rampage—Two Horses Killed, Four Wagons, and Three Railway Cars Derailed—Forty or Fifty Shots Fired at Him Without Effect.” The story took up the entire front page.

Samson the elephant escaped its handlers perhaps when a dog barked and another bit him on the trunk. This angered Samson so much that he attacked the lion cage, rolling it over three times and breaking two of the bars, but not freeing the lions. Circus men came with sledge hammers and crowbars trying to guide the elephant. Local men ran to Hailey Iron Works with the idea that bars heated white hot might serve to control the him. Meanwhile, two men on horseback—perhaps descended from Paul Revere—loped down Main Street yelling, “Samson is loose—smashing things. Get some guns to shoot him!”

Samson was crushing wagons and horses on his way toward town where he met up with a circus hand brandishing a white-hot poker, which he applied to Samson’s leg. The elephant howled and proceeded into town.

“At this time,” the Times reported, “there were fully 3,000 persons on the ground, looking on and following the movements of the mammoth with the…most intense excitement.”

And what about all that shouting for guns? “The cavaliers who ran to Main street to look for gun-men did not search in vain. Instantly 15 or 20 guns of all description, from the small bird shotgun to the heaviest two-ounce Winchester, were produced, and started for the scene of the rampage. An elephant hunt was just what the sports of Hailey had longed for for a long time.”

The men with rifles blasted away at the elephant with seemingly little effect, other than to turn him toward the railroad tracks. There he encountered a rail car loaded with ties, butting it with his head, then turning it over, knocking two more tie cars off the tracks. The ties, scattered around like matchsticks, made it difficult for Sampson to stand. This gave the circus men a chance to get ropes around him. After all that he was reportedly lead back to his tent “gentle as a lamb.”

At least six or seven shots the animal suffered seemed serious, but his trainer, Mr. Conklin, assured that he would “heal in a week or two.” The man said that, “about once a year… Samson gets vicious and is apt to give lots of trouble. But after the spell is over he is all right for another year.”

The paper speculated that the incident may have started when Samson saw “one of the smaller elephants caressing one of the females and possibly making an appointment with her.”

#circuselephant #idahohistory

The first circus to appear in Idaho Territory put on a show August 6, 1864 in Boise. It was Don Rice’s circus, which the Idaho Statesman at the time noted “everyone has seen…in one part of the world or another.”

World renown was apparently the norm for circuses. The ad below is from the Idaho Statesman, June 8, 1865. Note that it is billed as the “most attractive performance ever presented to the world.” And only a buck!

Hyperbole aside, those circuses couldn’t match the spectacle that took place in Hailey as reported in the Daily Wood River Times on August 4, 1884. If you tend to get queasy about animal injury, skip this.

The headline about Cole’s Circus said, “Samson, the Huge Elephant, on the Rampage—Two Horses Killed, Four Wagons, and Three Railway Cars Derailed—Forty or Fifty Shots Fired at Him Without Effect.” The story took up the entire front page.

Samson the elephant escaped its handlers perhaps when a dog barked and another bit him on the trunk. This angered Samson so much that he attacked the lion cage, rolling it over three times and breaking two of the bars, but not freeing the lions. Circus men came with sledge hammers and crowbars trying to guide the elephant. Local men ran to Hailey Iron Works with the idea that bars heated white hot might serve to control the him. Meanwhile, two men on horseback—perhaps descended from Paul Revere—loped down Main Street yelling, “Samson is loose—smashing things. Get some guns to shoot him!”

Samson was crushing wagons and horses on his way toward town where he met up with a circus hand brandishing a white-hot poker, which he applied to Samson’s leg. The elephant howled and proceeded into town.

“At this time,” the Times reported, “there were fully 3,000 persons on the ground, looking on and following the movements of the mammoth with the…most intense excitement.”

And what about all that shouting for guns? “The cavaliers who ran to Main street to look for gun-men did not search in vain. Instantly 15 or 20 guns of all description, from the small bird shotgun to the heaviest two-ounce Winchester, were produced, and started for the scene of the rampage. An elephant hunt was just what the sports of Hailey had longed for for a long time.”

The men with rifles blasted away at the elephant with seemingly little effect, other than to turn him toward the railroad tracks. There he encountered a rail car loaded with ties, butting it with his head, then turning it over, knocking two more tie cars off the tracks. The ties, scattered around like matchsticks, made it difficult for Sampson to stand. This gave the circus men a chance to get ropes around him. After all that he was reportedly lead back to his tent “gentle as a lamb.”

At least six or seven shots the animal suffered seemed serious, but his trainer, Mr. Conklin, assured that he would “heal in a week or two.” The man said that, “about once a year… Samson gets vicious and is apt to give lots of trouble. But after the spell is over he is all right for another year.”

The paper speculated that the incident may have started when Samson saw “one of the smaller elephants caressing one of the females and possibly making an appointment with her.”

#circuselephant #idahohistory

Published on May 19, 2019 04:00

May 18, 2019

Emma Edwards Green

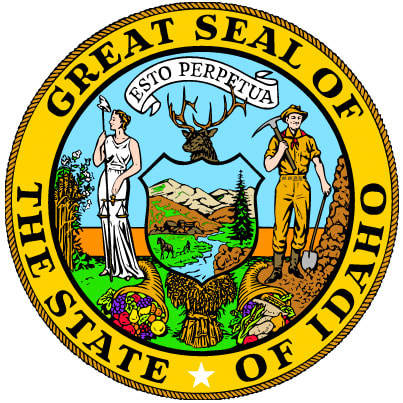

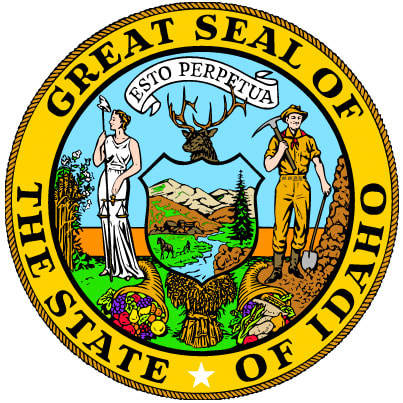

The great seal of the State of Idaho can be found on business cards, letterhead, brochures, proclamations, and other official state documents, and it is the centerpiece of Idaho's flag.

Emma Edwards Green, who was born in California and was the daughter of a former governor of Missouri, was teaching art classes in Boise when the brand new Idaho Legislature announced a contest for the design of a state seal. She entered the competition and won $100. To this day, it remains the only state seal designed by a woman.

Green got much input regarding the seal. She wrote, “Before designing the seal, I was careful to make a thorough study of the resources and future possibilities of the State. I invited the advice and counsel of every member of the Legislature and other citizens qualified to help in creating a Seal of State that really represented Idaho at that time.”

Green also gave it a lot of thought, writing, “The question of Woman Suffrage was being agitated somewhat, and as leading men and politicians agreed that Idaho would eventually give women the right to vote, and as mining was the chief industry, and the mining man the largest financial factor of the state at that time, I made the figure of the man the most prominent in the design, while that of the woman, signifying justice, as noted by the scales; liberty, as denoted by the liberty cap on the end of the spear, and equality with man as denoted by her position at his side, also signifies freedom. The pick and shovel held by the miner, and the ledge of rock beside which he stands, as well as the pieces of ore scattered about his feet, all indicate the chief occupation of the State. The stamp mill in the distance, which you can see by using a magnifying glass, is also typical of the mining interest of Idaho. The shield between the man and woman is emblematic of the protection they unite in giving the state. The large fir or pine tree in the foreground in the shield refers to Idaho’s immense timber interests. The husbandman plowing on the left side of the shield, together with the sheaf of grain beneath the shield, are emblematic of Idaho’s agricultural resources, while the cornucopias, or horns of plenty, refer to the horticultural. Idaho has a game law, which protects the elk and moose. The elk’s head, therefore, rises above the shield. The state flower, the wild Syringa or Mock Orange, grows at the woman’s feet, while the ripened wheat grows as high as her shoulder. The star signifies a new light in the galaxy of states… The river depicted in the shield is our mighty Snake or Shoshone River, a stream of great majesty.

“In regard to the coloring of the emblems used in the making of the Great Seal of the State of Idaho, my principal desire was to use such colors as would typify pure Americanism and the history of the State. As Idaho was a virgin state, I robed my goddess in white and made the liberty cap on the end of the spear the same color. In representing the miner, I gave him the garb of the period suggested by such mining authorities as former United States Senator George Shoup, of Idaho, former Governor Norman B. Willey of Idaho, former Governor James H. Hawley of Idaho, and other mining men and early residents of the state who knew intimately the usual garb of the miner. Almost unanimously they said, ‘Do not put the miner in a red shirt.” “Make the shirt a grayish brown,’ said Captain J.J. Wells, chairman of the Seal Committee. The ‘Light of the Mountains’ is typified by the rosy glow which precedes the sunrise.”

If that sounds a little busy to you, you would not be alone. The state seal was updated in 1957 to simplify it a bit, though it remains, let’s say, hard working. Emma Edwards Green, from the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Emma Edwards Green, from the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Emma Edwards Green, who was born in California and was the daughter of a former governor of Missouri, was teaching art classes in Boise when the brand new Idaho Legislature announced a contest for the design of a state seal. She entered the competition and won $100. To this day, it remains the only state seal designed by a woman.

Green got much input regarding the seal. She wrote, “Before designing the seal, I was careful to make a thorough study of the resources and future possibilities of the State. I invited the advice and counsel of every member of the Legislature and other citizens qualified to help in creating a Seal of State that really represented Idaho at that time.”

Green also gave it a lot of thought, writing, “The question of Woman Suffrage was being agitated somewhat, and as leading men and politicians agreed that Idaho would eventually give women the right to vote, and as mining was the chief industry, and the mining man the largest financial factor of the state at that time, I made the figure of the man the most prominent in the design, while that of the woman, signifying justice, as noted by the scales; liberty, as denoted by the liberty cap on the end of the spear, and equality with man as denoted by her position at his side, also signifies freedom. The pick and shovel held by the miner, and the ledge of rock beside which he stands, as well as the pieces of ore scattered about his feet, all indicate the chief occupation of the State. The stamp mill in the distance, which you can see by using a magnifying glass, is also typical of the mining interest of Idaho. The shield between the man and woman is emblematic of the protection they unite in giving the state. The large fir or pine tree in the foreground in the shield refers to Idaho’s immense timber interests. The husbandman plowing on the left side of the shield, together with the sheaf of grain beneath the shield, are emblematic of Idaho’s agricultural resources, while the cornucopias, or horns of plenty, refer to the horticultural. Idaho has a game law, which protects the elk and moose. The elk’s head, therefore, rises above the shield. The state flower, the wild Syringa or Mock Orange, grows at the woman’s feet, while the ripened wheat grows as high as her shoulder. The star signifies a new light in the galaxy of states… The river depicted in the shield is our mighty Snake or Shoshone River, a stream of great majesty.

“In regard to the coloring of the emblems used in the making of the Great Seal of the State of Idaho, my principal desire was to use such colors as would typify pure Americanism and the history of the State. As Idaho was a virgin state, I robed my goddess in white and made the liberty cap on the end of the spear the same color. In representing the miner, I gave him the garb of the period suggested by such mining authorities as former United States Senator George Shoup, of Idaho, former Governor Norman B. Willey of Idaho, former Governor James H. Hawley of Idaho, and other mining men and early residents of the state who knew intimately the usual garb of the miner. Almost unanimously they said, ‘Do not put the miner in a red shirt.” “Make the shirt a grayish brown,’ said Captain J.J. Wells, chairman of the Seal Committee. The ‘Light of the Mountains’ is typified by the rosy glow which precedes the sunrise.”

If that sounds a little busy to you, you would not be alone. The state seal was updated in 1957 to simplify it a bit, though it remains, let’s say, hard working.

Emma Edwards Green, from the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Emma Edwards Green, from the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Published on May 18, 2019 04:00

May 17, 2019

Tick Tock

Time is of some importance when you’re running the government, especially at the statehouse where committee meetings follow a published agenda. It was important enough in the early days of Idaho’s capitol that they installed a system of clocks each controlled by a single master clock. The master clock stood about six feet high with a pendulum the size of dinner plate.

Problems with the system developed almost immediately.

The September 20th, 1914, Idaho Statesman reported that “All the clocks in the capitol building proper are regulated and set every few minutes by the master clock in the office of the state board of health on the top floor, and as this has been out of order for some time the whole system has been stopped, and for some reason each separate instrument stopped at a different hour.”

This resulted in some confusion as visitors moved about inside the statehouse only to find that time seemed to be rushing ahead or falling back at random according to the 27 clocks on the system.

The clocks throughout the building were notorious for not working. They went for years at a time without moving at all, offering a “wide variety of time.” They underwent repair several times, costing taxpayers about $500 per fix, each of which would last a week or two. It wasn’t long before maintenance staff just gave up.

At least a couple of times a Statesman reporter would take it upon himself to report the time in various offices to goad the government a bit. In several state offices they covered the clocks to avoid confusion. And embarrassment.

One clock was so thoroughly covered that it disappeared even from memory. An ornate clock behind the justices of the Idaho Supreme Court was covered by a false wall. That room became the setting for the Joint Finance and Appropriation Committee meetings when the court got its own building. The clock was rediscovered during the repair and remodel following the statehouse fire in 1992, and was restored to its original grandeur (see photo). It is the last of the capitol clocks that once—occasionally—ran on signals from the master clock. The mechanism has been replaced so that it ACTUALLY TELLS TIME.

Thanks to Capitol Curator Michelle Wallace for giving me the tip that led to this story.

#idahohistory #idahocapitol #boisehistory #boise

Problems with the system developed almost immediately.

The September 20th, 1914, Idaho Statesman reported that “All the clocks in the capitol building proper are regulated and set every few minutes by the master clock in the office of the state board of health on the top floor, and as this has been out of order for some time the whole system has been stopped, and for some reason each separate instrument stopped at a different hour.”

This resulted in some confusion as visitors moved about inside the statehouse only to find that time seemed to be rushing ahead or falling back at random according to the 27 clocks on the system.

The clocks throughout the building were notorious for not working. They went for years at a time without moving at all, offering a “wide variety of time.” They underwent repair several times, costing taxpayers about $500 per fix, each of which would last a week or two. It wasn’t long before maintenance staff just gave up.

At least a couple of times a Statesman reporter would take it upon himself to report the time in various offices to goad the government a bit. In several state offices they covered the clocks to avoid confusion. And embarrassment.

One clock was so thoroughly covered that it disappeared even from memory. An ornate clock behind the justices of the Idaho Supreme Court was covered by a false wall. That room became the setting for the Joint Finance and Appropriation Committee meetings when the court got its own building. The clock was rediscovered during the repair and remodel following the statehouse fire in 1992, and was restored to its original grandeur (see photo). It is the last of the capitol clocks that once—occasionally—ran on signals from the master clock. The mechanism has been replaced so that it ACTUALLY TELLS TIME.

Thanks to Capitol Curator Michelle Wallace for giving me the tip that led to this story.

#idahohistory #idahocapitol #boisehistory #boise

Published on May 17, 2019 04:00

May 16, 2019

Sister History

Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn created a tiny little museum in an attic at St. Gertrude’s Academy in Cottonwood in 1931. It was a way to teach her students about history, geology, biology, and other subjects. The little museum grew bit by bit over the years until today—now in its own modern building—it has more than 70,000 items.

The Historical Museum at St. Gertrude has a special collection of Nez Perce artifacts, an extensive geology exhibit, a medical collection, extensive displays on the Chinese in Idaho, and a pioneer life collection. There is an exhibit about the history of the Monastery of St. Gertrude, which you might expect. You would not expect the Rhoades Emmanuel Gallery, which features the lifetime collection of Winifred Rhoades, a renowned silent film organist whose interest include European and Asian artifacts. Yes, you’ll see Ming Dynasty vases right there on the Camas Prairie.

The museum is home to the collections of well-known Idaho County personalities Polly Bemis, Frances Wisner, and Sylvan “Buckskin Bill” Hart.

It is a collection that rivals any other in the state, and something that would have made Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn famous on its own. But she wasn’t satisfied teaching only students. She became an important Idaho historian, writing books such as Pioneer Days in Idaho County , Idaho Chinese Lore , and Polly Bemis . With her writing and teaching, Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn became one of Idaho’s most important historians.

#idaho #idahocounty #stgertrude #historicalmuseumatstgertrude #pollybemis Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn autographing books in 1952. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical collection.

Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn autographing books in 1952. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical collection.

The Historical Museum at St. Gertrude has a special collection of Nez Perce artifacts, an extensive geology exhibit, a medical collection, extensive displays on the Chinese in Idaho, and a pioneer life collection. There is an exhibit about the history of the Monastery of St. Gertrude, which you might expect. You would not expect the Rhoades Emmanuel Gallery, which features the lifetime collection of Winifred Rhoades, a renowned silent film organist whose interest include European and Asian artifacts. Yes, you’ll see Ming Dynasty vases right there on the Camas Prairie.

The museum is home to the collections of well-known Idaho County personalities Polly Bemis, Frances Wisner, and Sylvan “Buckskin Bill” Hart.

It is a collection that rivals any other in the state, and something that would have made Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn famous on its own. But she wasn’t satisfied teaching only students. She became an important Idaho historian, writing books such as Pioneer Days in Idaho County , Idaho Chinese Lore , and Polly Bemis . With her writing and teaching, Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn became one of Idaho’s most important historians.

#idaho #idahocounty #stgertrude #historicalmuseumatstgertrude #pollybemis

Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn autographing books in 1952. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical collection.

Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn autographing books in 1952. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical collection.

Published on May 16, 2019 04:00

May 15, 2019

The Aesthetics of Butter

A personal indulgence, today. One of my favorite stories from my family history. The following was taken from the book Letters of Long Ago by Agnes Just Reid, first published in 1923, and available today in its fourth edition on Amazon. Nels and Emma Just were my great grandparents. Emma is writing to her father in England.

“The winter was uneventful, but the spring, the spring has been wonderful! We have had guests, distinguished guests from the big world itself. You see there is a land to the northeast of us, perhaps a hundred miles, that is considered marvelous for its scenic possibilities and the government is sending a party of surveyors, chemists, etc., to pass judgment with a view to setting it aside for a national park. Well, this party happened to stop at our little cabin. There were representatives from all of the big eastern colleges, and then besides, there were the Moran brothers. I think you must have heard of Thomas Moran even as far away as England, for he is a wonderful nature artist. And his brother John is what I have heard you speak of as a "book maker." He writes magazine articles.

“And these two remarkable men were interested in us and in our way of living. Think of it, Father! I took them into the cellar where I had been churning to give them a drink of fresh buttermilk and while they drank and enjoyed it, I was smoothing the rolls of butter with my cedar paddle that Nels had whittled out for me with his pocket knife. I noticed the artist man paying special attention to the process and finally he ventured rather apologetically: "Mrs. Just, would you mind telling me what you varnish your rolls of butter with that gives them such a glossy appearance?" I thought the man was making fun of me, or sport of me as you would express it, but I looked into his face and saw that it was all candor. That is one of the happiest experiences of my life for that man who knows everything to be ignorant in the lines that I know so well. I tried to make him understand that the smooth paddle and the fresh butter were all sufficient but I think he is still rather bewildered. And do you know, since that day, the art of butter making has taken on anew dignity. I always did like to do it, but now my cedar paddle keeps singing to me with every stroke, "Even Thomas Moran cannot do this, Thomas Moran cannot do this," and before I know it the butter is all finished and I am ready to sing a different song to the washboard.”

Thomas Moran, of course, was a member of the Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871. The expedition was camped nearby along the Blackfoot River on their way to Yellowstone, and several members visited the Just cabin. Emma and Nels sold them some of their handiwork. Some leather gloves and britches.

Family tradition has it that the britches in this photo, taken by another famous man that went along on that expedition, William Henry Jackson, were made by Emma.

#idahohistory #thomasmoran #williamhenryjackson #emmajust

“The winter was uneventful, but the spring, the spring has been wonderful! We have had guests, distinguished guests from the big world itself. You see there is a land to the northeast of us, perhaps a hundred miles, that is considered marvelous for its scenic possibilities and the government is sending a party of surveyors, chemists, etc., to pass judgment with a view to setting it aside for a national park. Well, this party happened to stop at our little cabin. There were representatives from all of the big eastern colleges, and then besides, there were the Moran brothers. I think you must have heard of Thomas Moran even as far away as England, for he is a wonderful nature artist. And his brother John is what I have heard you speak of as a "book maker." He writes magazine articles.

“And these two remarkable men were interested in us and in our way of living. Think of it, Father! I took them into the cellar where I had been churning to give them a drink of fresh buttermilk and while they drank and enjoyed it, I was smoothing the rolls of butter with my cedar paddle that Nels had whittled out for me with his pocket knife. I noticed the artist man paying special attention to the process and finally he ventured rather apologetically: "Mrs. Just, would you mind telling me what you varnish your rolls of butter with that gives them such a glossy appearance?" I thought the man was making fun of me, or sport of me as you would express it, but I looked into his face and saw that it was all candor. That is one of the happiest experiences of my life for that man who knows everything to be ignorant in the lines that I know so well. I tried to make him understand that the smooth paddle and the fresh butter were all sufficient but I think he is still rather bewildered. And do you know, since that day, the art of butter making has taken on anew dignity. I always did like to do it, but now my cedar paddle keeps singing to me with every stroke, "Even Thomas Moran cannot do this, Thomas Moran cannot do this," and before I know it the butter is all finished and I am ready to sing a different song to the washboard.”

Thomas Moran, of course, was a member of the Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871. The expedition was camped nearby along the Blackfoot River on their way to Yellowstone, and several members visited the Just cabin. Emma and Nels sold them some of their handiwork. Some leather gloves and britches.

Family tradition has it that the britches in this photo, taken by another famous man that went along on that expedition, William Henry Jackson, were made by Emma.

#idahohistory #thomasmoran #williamhenryjackson #emmajust

Published on May 15, 2019 04:00

May 14, 2019

The Original Longhorn

I’ve written a couple of posts about how the town of American Falls was moved when the dam was built and the resulting reservoir flooded the former town site. Creating that reservoir had many impacts, including the drowning of some historical sites. It also had a positive impact on the study of paleontology in Idaho.

The movement of water in the American Falls Reservoir has eroded some fossil sites, making them much more accessible. One example of that was the discovery of two gigantic longhorn bison--Bison latifrons, to use the scientific name. The first skull was uncovered by Wayne Whitlow, a zoology teacher at Pocatello High School. He and a student, Woodrow Benson, excavated the fossil in 1933. The tip of one horn gave it away, sticking out from the side of a cliff that had been exposed by the lapping waters of the reservoir.

An even better specimen, an adult female bison nicknamed Mary Lou by Merle Hopkins who discovered it, was found along the shores of the reservoir in 1947. The replica of that skull—the original is too fragile to display—can be seen at the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho.

Long-horned bison have been extinct for a while. The Idaho specimens probably lived between 72,000 and 75,000 years ago. They would have been about 8 feet tall at the shoulder, weighing more than two tons, making them the largest and heaviest bison known.

For a fascinating story about long-horned bison and the digitizing of fossils at ISU, check this story by Jennifer Huang from Idaho Magazine .

#Idahohistory #longhornedbison

Bison skull replica at the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho. On the left is a skull from a modern day bison for comparison.

Bison skull replica at the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho. On the left is a skull from a modern day bison for comparison.

The movement of water in the American Falls Reservoir has eroded some fossil sites, making them much more accessible. One example of that was the discovery of two gigantic longhorn bison--Bison latifrons, to use the scientific name. The first skull was uncovered by Wayne Whitlow, a zoology teacher at Pocatello High School. He and a student, Woodrow Benson, excavated the fossil in 1933. The tip of one horn gave it away, sticking out from the side of a cliff that had been exposed by the lapping waters of the reservoir.

An even better specimen, an adult female bison nicknamed Mary Lou by Merle Hopkins who discovered it, was found along the shores of the reservoir in 1947. The replica of that skull—the original is too fragile to display—can be seen at the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho.

Long-horned bison have been extinct for a while. The Idaho specimens probably lived between 72,000 and 75,000 years ago. They would have been about 8 feet tall at the shoulder, weighing more than two tons, making them the largest and heaviest bison known.

For a fascinating story about long-horned bison and the digitizing of fossils at ISU, check this story by Jennifer Huang from Idaho Magazine .

#Idahohistory #longhornedbison

Bison skull replica at the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho. On the left is a skull from a modern day bison for comparison.

Bison skull replica at the Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History at the College of Idaho. On the left is a skull from a modern day bison for comparison.

Published on May 14, 2019 04:00

May 13, 2019

Boise and Interurban Wreck

One often hears a lament from Boiseans regarding the long vanished Interurban. The conversation often goes that “we” made a mistake letting that system that looped around the Treasure Valley taking passengers between and within Boise, Star, Caldwell, and other locations slip from our grasp.

I’ve often said as much myself. But what is often forgotten is that it wasn’t a municipal system. It was a commercial system or, more properly, several commercial systems. The Interurban went away because it began to cost more to run than the revenue it brought in.

Also lost in the nostalgic dreams of cheap transportation for Sunday picnics and commuting workers is the fact that the Interurban was far from perfect. If you search through newspapers of the early teens and twenties, you’ll find dozens of references to fatal “electric car” crashes all over the country on interurban lines.

The Boise & Interurban had at least one fatal collision.

On the evening of July 20, 1910, two Boise & Interurban cars collided on Hill’s curve, a half mile west of Star. The motorman on the westbound car, William Earwood of Boise, was killed in the collision, while 16 passengers were injured, none seriously. A photo of one of the cars, below, is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The two cars were each going about 20 miles per hour at the time of the collision, which resulted when one or both conductors failed to contact dispatch for a check on traffic before entering the curve.

It is worth noting W.E. Pierce, the owner of the company, held that the Boise & Interurban was under no obligation to pay for Earwood’s death, since it was determined that he was at fault. Nevertheless, they did pay his widow $4,000.

#idahohistory #boise #boisehistory #interurban

I’ve often said as much myself. But what is often forgotten is that it wasn’t a municipal system. It was a commercial system or, more properly, several commercial systems. The Interurban went away because it began to cost more to run than the revenue it brought in.

Also lost in the nostalgic dreams of cheap transportation for Sunday picnics and commuting workers is the fact that the Interurban was far from perfect. If you search through newspapers of the early teens and twenties, you’ll find dozens of references to fatal “electric car” crashes all over the country on interurban lines.

The Boise & Interurban had at least one fatal collision.

On the evening of July 20, 1910, two Boise & Interurban cars collided on Hill’s curve, a half mile west of Star. The motorman on the westbound car, William Earwood of Boise, was killed in the collision, while 16 passengers were injured, none seriously. A photo of one of the cars, below, is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The two cars were each going about 20 miles per hour at the time of the collision, which resulted when one or both conductors failed to contact dispatch for a check on traffic before entering the curve.

It is worth noting W.E. Pierce, the owner of the company, held that the Boise & Interurban was under no obligation to pay for Earwood’s death, since it was determined that he was at fault. Nevertheless, they did pay his widow $4,000.

#idahohistory #boise #boisehistory #interurban

Published on May 13, 2019 04:00

May 12, 2019

Diamonds are a Girl's Best Friend

(Note: This is an update to an earlier story to include additional photos)

First, let’s concede that there were at least a couple of women who went by the name of Diamond Tooth Lil. One, real name Honora Ornstein, was a vaudeville performer well-known in Klondike Gold Rush days. Her affectation of diamonds included much jewelry and several gold teeth studded with diamonds.

Idaho’s Diamond Tooth Lil was an entertainer and entrepreneur who bounced around the West from Silver City to San Francisco, spending significant time in Boise as a manager of rooming houses which were rumored to offer unadvertised recreational activities. Her birth name was Evelyn Fialla (some sources say Prado was her last name), and she was born in Austria-Hungary in about 1877. She married at least eight times, but the name she preferred to use was her first husband’s surname of Hildegard. Everyone else preferred Diamond Tooth Lil.

Lil loved to tell the story of her life to any reporter who would listen. She often told about her gold right front tooth with the diamond, about 1/3 carat, mounted in the center of it. She won that piece of art from a Reno dentist in a bet on a horse race in 1907. More than once she promised to leave the tooth and its diamond to the Idaho Children’s Home orphanage. What finally happened to it is open to speculation.

Diamond Tooth Lil’s stories were often about the love of her life, Diamondfield Jack. They spent time with each other over the years in Idaho and Nevada. She said he asked her to marry him many times, but she declined. They lost track of each other for 30 years, but reunited briefly at a Las Vegas casino in 1946, and in Los Angeles shortly before his death.

When Diamondfield Jack was struck by a cab in 1946 at age 84, it was Diamond Tooth Lil who alerted the Idaho Statesman. Before his death she reported that he had exonerated the taxi driver, saying, “I just wasn’t looking where I was going.”

She ran an auto court called the Depot Inn on the bench near the Boise Depot, and a hotel at 219 S. Ninth, among other Boise properties. She moved to Los Angeles to retire in 1943 but visited Boise regularly. In 1953 she sent photos and other items to the Boise Chamber of Commerce with a note, “just sending a little momento (sic), so you’ll not forget me.”

There’s little chance Diamond Tooth Lil will be forgotten. Mae West wrote a successful Broadway play called Diamond Lil in 1928, which was turned into a movie called She Done Him Wrong, and was revived on Broadway in 1949. Many say it was inspired by one Diamond Tooth Lil or the other, or perhaps the pair of them.

#diamondtoothlil #idahohistory #diamondfieldjack

There’s that diamond! Look closely at this photo. You can’t make out much, but she clearly has something going on with that top left front tooth. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

There’s that diamond! Look closely at this photo. You can’t make out much, but she clearly has something going on with that top left front tooth. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Evelyn Fialla Hildegard operated “boarding houses” in Boise. She called herself Diamond Tooth Lil and sometimes Mrs. Evelynn Hill, but always signed her name as Evelyn Fialla Hildegard. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Evelyn Fialla Hildegard operated “boarding houses” in Boise. She called herself Diamond Tooth Lil and sometimes Mrs. Evelynn Hill, but always signed her name as Evelyn Fialla Hildegard. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

First, let’s concede that there were at least a couple of women who went by the name of Diamond Tooth Lil. One, real name Honora Ornstein, was a vaudeville performer well-known in Klondike Gold Rush days. Her affectation of diamonds included much jewelry and several gold teeth studded with diamonds.

Idaho’s Diamond Tooth Lil was an entertainer and entrepreneur who bounced around the West from Silver City to San Francisco, spending significant time in Boise as a manager of rooming houses which were rumored to offer unadvertised recreational activities. Her birth name was Evelyn Fialla (some sources say Prado was her last name), and she was born in Austria-Hungary in about 1877. She married at least eight times, but the name she preferred to use was her first husband’s surname of Hildegard. Everyone else preferred Diamond Tooth Lil.

Lil loved to tell the story of her life to any reporter who would listen. She often told about her gold right front tooth with the diamond, about 1/3 carat, mounted in the center of it. She won that piece of art from a Reno dentist in a bet on a horse race in 1907. More than once she promised to leave the tooth and its diamond to the Idaho Children’s Home orphanage. What finally happened to it is open to speculation.

Diamond Tooth Lil’s stories were often about the love of her life, Diamondfield Jack. They spent time with each other over the years in Idaho and Nevada. She said he asked her to marry him many times, but she declined. They lost track of each other for 30 years, but reunited briefly at a Las Vegas casino in 1946, and in Los Angeles shortly before his death.

When Diamondfield Jack was struck by a cab in 1946 at age 84, it was Diamond Tooth Lil who alerted the Idaho Statesman. Before his death she reported that he had exonerated the taxi driver, saying, “I just wasn’t looking where I was going.”

She ran an auto court called the Depot Inn on the bench near the Boise Depot, and a hotel at 219 S. Ninth, among other Boise properties. She moved to Los Angeles to retire in 1943 but visited Boise regularly. In 1953 she sent photos and other items to the Boise Chamber of Commerce with a note, “just sending a little momento (sic), so you’ll not forget me.”

There’s little chance Diamond Tooth Lil will be forgotten. Mae West wrote a successful Broadway play called Diamond Lil in 1928, which was turned into a movie called She Done Him Wrong, and was revived on Broadway in 1949. Many say it was inspired by one Diamond Tooth Lil or the other, or perhaps the pair of them.

#diamondtoothlil #idahohistory #diamondfieldjack

There’s that diamond! Look closely at this photo. You can’t make out much, but she clearly has something going on with that top left front tooth. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

There’s that diamond! Look closely at this photo. You can’t make out much, but she clearly has something going on with that top left front tooth. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives. Evelyn Fialla Hildegard operated “boarding houses” in Boise. She called herself Diamond Tooth Lil and sometimes Mrs. Evelynn Hill, but always signed her name as Evelyn Fialla Hildegard. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Evelyn Fialla Hildegard operated “boarding houses” in Boise. She called herself Diamond Tooth Lil and sometimes Mrs. Evelynn Hill, but always signed her name as Evelyn Fialla Hildegard. Photo courtesy of the physical photo collection of the Idaho State Archives.

Published on May 12, 2019 04:00

May 11, 2019

Fun for Beavers?

Do you know what a beaver slide is? If you’re a beaver fan, you’ll probably assume I’m talking about a muddy little path that serves as a quick way to get into the water for your favorite rodent.

The beaver slide I have in mind was once used to stack hay all over the West. It was patented as the Beaver County Slide Stacker in the early 1900s. Invented in the Big Hole Valley in Montana, it’s a somewhat portable device, made of wood, that lets someone with a team of horses pull a big wad of hay up the slide and topple it off onto a stack. Before bailing became the thing to do, loose hay in stacks was a way to store and preserve it. Hay stacked that way can last a couple of years—maybe as many as six years, if conditions are right.

The name was popularly shortened to beaver slide by those who used it. Nowadays you’re more likely to see a roll of hay the size of a Volkswagen than a beaver slide and a loose stack. However, the University of Montana notes that a few ranchers are going back to this method because it saves money and fuel.

The beaver slide in the picture was being run by Nona Virgin on the Railroad Ranch in the Island Park country, probably in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and Harriman State Park.

#idahohistory #beaverslide #harrimanstatepark

The beaver slide I have in mind was once used to stack hay all over the West. It was patented as the Beaver County Slide Stacker in the early 1900s. Invented in the Big Hole Valley in Montana, it’s a somewhat portable device, made of wood, that lets someone with a team of horses pull a big wad of hay up the slide and topple it off onto a stack. Before bailing became the thing to do, loose hay in stacks was a way to store and preserve it. Hay stacked that way can last a couple of years—maybe as many as six years, if conditions are right.

The name was popularly shortened to beaver slide by those who used it. Nowadays you’re more likely to see a roll of hay the size of a Volkswagen than a beaver slide and a loose stack. However, the University of Montana notes that a few ranchers are going back to this method because it saves money and fuel.

The beaver slide in the picture was being run by Nona Virgin on the Railroad Ranch in the Island Park country, probably in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and Harriman State Park.

#idahohistory #beaverslide #harrimanstatepark

Published on May 11, 2019 04:00

May 10, 2019

That 1909 Mazda

I drove Mazda Miatas for about 14 years, which is not worthy of mention in a history blog, except that it will explain why I do a little double-take when I see a Mazda ad from 1909.

Mazda was the brand name for incandescent lighting products from GE and Westinghouse from 1909 to 1945, so you see ads for the product scattered through the pages of newspapers from that time period. When calling for bids on illumination for the new Capitol Bridge in Boise in 1931, they specified “ornamental mazda incandescent lights.” And, yes, they forgot to capitalize the brand name in the legal notice.

So, no, they weren’t driving Japanese convertibles back in the early part of the 20th century. There is a connection to my little roadsters, though. The Mazda trademark, which GE let drop in 2,000, was shared with the Japanese car company for many years, applying to electrical lighting for GE, and automobiles for Mazda.

Mazda was the brand name for incandescent lighting products from GE and Westinghouse from 1909 to 1945, so you see ads for the product scattered through the pages of newspapers from that time period. When calling for bids on illumination for the new Capitol Bridge in Boise in 1931, they specified “ornamental mazda incandescent lights.” And, yes, they forgot to capitalize the brand name in the legal notice.

So, no, they weren’t driving Japanese convertibles back in the early part of the 20th century. There is a connection to my little roadsters, though. The Mazda trademark, which GE let drop in 2,000, was shared with the Japanese car company for many years, applying to electrical lighting for GE, and automobiles for Mazda.

Published on May 10, 2019 04:00