Rick Just's Blog, page 201

April 19, 2019

How to eat Camas without Dying

Camas bulbs were important enough to the Bannock Indians that they went to war over them in 1878. Have you ever wondered how they were used?

Well, they ate them, of course. But the indigenous people who depended on the root did not simply dig them up and start chewing. Camas bulbs are reportedly nasty if eaten raw. They have a soapy taste and get gummy when you chew them, making the whole mess stick to your teeth.

So, cooking, then. The women of the tribe would dig them up in the spring and, after removing the papery sheath from the bulbs, cook them in earthen ovens. These ovens were pits lined with rocks. The women put alternating layers of grass and camas bulbs into the pits and covered them with soil. Once the layering was completed, they would build a fire on top of the pit. The rocks would retain the heat and cook the one- to two-inch bulbs. It took several days.

Once cooked camas bulbs are sweet. Some have described their taste as something like a baked pear or a water chestnut.

Since we’re talking about eating camas bulbs, we should note that you don’t want to sample Death Camas. You’re not likely to confuse the plants in the field, at least when they are in bloom. Death Camas, which blooms later in June, has white flowers that are more tightly arranged the brilliant blue flowers of the edible variety. No part of the Death Camas is edible.

Maybe you should just enjoy the blossoms.

Well, they ate them, of course. But the indigenous people who depended on the root did not simply dig them up and start chewing. Camas bulbs are reportedly nasty if eaten raw. They have a soapy taste and get gummy when you chew them, making the whole mess stick to your teeth.

So, cooking, then. The women of the tribe would dig them up in the spring and, after removing the papery sheath from the bulbs, cook them in earthen ovens. These ovens were pits lined with rocks. The women put alternating layers of grass and camas bulbs into the pits and covered them with soil. Once the layering was completed, they would build a fire on top of the pit. The rocks would retain the heat and cook the one- to two-inch bulbs. It took several days.

Once cooked camas bulbs are sweet. Some have described their taste as something like a baked pear or a water chestnut.

Since we’re talking about eating camas bulbs, we should note that you don’t want to sample Death Camas. You’re not likely to confuse the plants in the field, at least when they are in bloom. Death Camas, which blooms later in June, has white flowers that are more tightly arranged the brilliant blue flowers of the edible variety. No part of the Death Camas is edible.

Maybe you should just enjoy the blossoms.

Published on April 19, 2019 04:00

April 18, 2019

The Standrod Mansion

One of Idaho’s most beautiful homes is the Standrod Mansion in Pocatello. Bonus: It may be haunted.

Drew W. Standrod was a lawyer in Malad City, Idaho in 1890 when he became a member of Idaho’s constitutional convention. He was later elected Fifth Judicial District State Judge. His district covered what are now the counties of Oneida, Bannock, Bingham, Fremont, Lemhi, Custer, and Bear Lake. In 1895 he and his family moved to Pocatello to be more centrally located in his district. He served as a judge until 1899 when he went into private practice in Pocatello.

Standrod was also a financier, serving on the boards of the Standrod and Company Bank in Blackfoot, and the J.N. Ireland and Company Bank in Malad. Those banks led to the creation of banks still well-known in Idaho, Ireland Bank and D.L. Evans Bank. Standrod was also a partner in the Yellowstone Hotel in Pocatello.

D.W. Standrod became a member of Idaho’s first Public Utilities Commission and as such wrote much of the irrigation and water rights law in use today.

Lest one think that he was a success at everything, it should be noted that he ran for a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court and for governor of the state, losing in both campaigns.

Emma Standrod, his wife, was a school principal and founder of the Wyeth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in historical preservation and the Red Cross.

The Standrods built their mansion in 1902 using mostly local materials. The two-story home is one of only a few in the state built in the Châteauesque style, a revival style based on the French Renaissance architecture of the monumental French country houses. The prominent corner tower gives the home a castle-like—some might say forbidding—appearance. It would not be out of place in a Charles Addams cartoon from the New Yorker. Perhaps that bolsters the ghost stories attached to the mansion.

Legend has it that daughter Cammie Standrod, distraught over the disappearance of a boyfriend her father did not approve of, died in that iconic tower. She is said to have had a kidney disease and in her weakened state caught a cold that proved her demise. Cammie is the star of most stories of haunting, though some mention the ghostly image of an elderly man, perhaps D.W. himself, who also died in his mansion.

Though the City of Pocatello owned the home for about 20 years, the Standrod Mansion is now a private residence.

#standrodmansion #stanrodmansion

Drew W. Standrod was a lawyer in Malad City, Idaho in 1890 when he became a member of Idaho’s constitutional convention. He was later elected Fifth Judicial District State Judge. His district covered what are now the counties of Oneida, Bannock, Bingham, Fremont, Lemhi, Custer, and Bear Lake. In 1895 he and his family moved to Pocatello to be more centrally located in his district. He served as a judge until 1899 when he went into private practice in Pocatello.

Standrod was also a financier, serving on the boards of the Standrod and Company Bank in Blackfoot, and the J.N. Ireland and Company Bank in Malad. Those banks led to the creation of banks still well-known in Idaho, Ireland Bank and D.L. Evans Bank. Standrod was also a partner in the Yellowstone Hotel in Pocatello.

D.W. Standrod became a member of Idaho’s first Public Utilities Commission and as such wrote much of the irrigation and water rights law in use today.

Lest one think that he was a success at everything, it should be noted that he ran for a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court and for governor of the state, losing in both campaigns.

Emma Standrod, his wife, was a school principal and founder of the Wyeth Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She was active in historical preservation and the Red Cross.

The Standrods built their mansion in 1902 using mostly local materials. The two-story home is one of only a few in the state built in the Châteauesque style, a revival style based on the French Renaissance architecture of the monumental French country houses. The prominent corner tower gives the home a castle-like—some might say forbidding—appearance. It would not be out of place in a Charles Addams cartoon from the New Yorker. Perhaps that bolsters the ghost stories attached to the mansion.

Legend has it that daughter Cammie Standrod, distraught over the disappearance of a boyfriend her father did not approve of, died in that iconic tower. She is said to have had a kidney disease and in her weakened state caught a cold that proved her demise. Cammie is the star of most stories of haunting, though some mention the ghostly image of an elderly man, perhaps D.W. himself, who also died in his mansion.

Though the City of Pocatello owned the home for about 20 years, the Standrod Mansion is now a private residence.

#standrodmansion #stanrodmansion

Published on April 18, 2019 04:00

April 17, 2019

Puttin' out the Paper

In the 1870s it was often a challenge for the staff of the Idaho Statesman and the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman to get the paper out. First, someone had to be found to turn the press. The single cylinder Acme press was hand operated, often by a Chinese laborer. If someone could not be found to crank the machine, it fell to the staff. Everyone from the editor on down took their turn at the wheel to keep the press running.

It was not always labor that was in short supply. The paper to feed through the press was brought in by freight teams from Kelton, Utah. Except when it wasn’t. If the newsprint failed to show, there was a scramble to find anything that would take ink. Butcher paper and grocery store paper sometimes filled in for the real thing.

The tri-weekly version of the paper had a circulation of about 1200 copies, and the weekly ran about 800 copies. That was a lot of folding. In those early days the newspapers had to be folded by hand by everyone in the office.

Charles Payton, who worked for the Statesman in the 1870s, reminisced about the early days in the December 15, 1918 edition of the paper. He remembered an irate subscriber that burst into the office one day. Payton had gotten a little ahead of the game by writing the man’s obituary. The man was on death’s door, so the paper printed it. Apparently the reportedly dead subscriber had decided not to knock on the door of death. Instead he stopped by to complain vehemently that his demise had been prematurely printed in the paper. Mark Twain, it is said, had a similar experience.

It was not always labor that was in short supply. The paper to feed through the press was brought in by freight teams from Kelton, Utah. Except when it wasn’t. If the newsprint failed to show, there was a scramble to find anything that would take ink. Butcher paper and grocery store paper sometimes filled in for the real thing.

The tri-weekly version of the paper had a circulation of about 1200 copies, and the weekly ran about 800 copies. That was a lot of folding. In those early days the newspapers had to be folded by hand by everyone in the office.

Charles Payton, who worked for the Statesman in the 1870s, reminisced about the early days in the December 15, 1918 edition of the paper. He remembered an irate subscriber that burst into the office one day. Payton had gotten a little ahead of the game by writing the man’s obituary. The man was on death’s door, so the paper printed it. Apparently the reportedly dead subscriber had decided not to knock on the door of death. Instead he stopped by to complain vehemently that his demise had been prematurely printed in the paper. Mark Twain, it is said, had a similar experience.

Published on April 17, 2019 04:00

April 16, 2019

Paul Bunyan in Idaho

So, did you know that Paul Bunyan has an Idaho connection? Stories about Paul Bunyan and his giant blue ox, Babe, circulated around lumber camps across the country for decades before anyone thought to write them down and publish them. Eventually, many people did. One of the best remembered tellers of those tales was author James Stevens who spent much of his childhood in Idaho. Sinclair Lewis called Stevens “the true son of Paul Bunyan.”

Stevens was a soldier in France during World War I. He did more than fight, though. He published his Paul Bunyan stories in Stars and Stripes.

After the war he knocked around the country as an itinerant laborer, educating himself in local libraries wherever he went. He published poetry in Saturday Evening Post, and more Paul Bunyan stories in American Mercury.

Stevens’ 1945 novel Big Jim Turner, about an itinerant working man and poet who grew up around Knox, Idaho (now a ghost town), has many autobiographical elements in it.

His best-known work, though, is probably his Paul Bunyan book (pictured), published in 1925. Stevens died in Seattle in 1971.

#paulbunyon #jimstevens #jamesstevens

Stevens was a soldier in France during World War I. He did more than fight, though. He published his Paul Bunyan stories in Stars and Stripes.

After the war he knocked around the country as an itinerant laborer, educating himself in local libraries wherever he went. He published poetry in Saturday Evening Post, and more Paul Bunyan stories in American Mercury.

Stevens’ 1945 novel Big Jim Turner, about an itinerant working man and poet who grew up around Knox, Idaho (now a ghost town), has many autobiographical elements in it.

His best-known work, though, is probably his Paul Bunyan book (pictured), published in 1925. Stevens died in Seattle in 1971.

#paulbunyon #jimstevens #jamesstevens

Published on April 16, 2019 04:00

April 15, 2019

The Block that isn't

If you’re familiar with a near-block-long group of stone buildings between Capitol Boulevard and 8th Street in downtown Boise, you probably know those structures as the Union Block. You’re right, but also a little wrong.

The 125-foot-wide building in the center of these structures is actually the Union Block all by itself, as it says on the sandstone façade. It was designed in 1899 by architect John E. Tourellotte and completed in 1902. This was during a little building boom in Boise. As plans were announced for the Union Block adjacent property owners jumped on the bandwagon, matching facades on their buildings to that of the Union Block. The Idaho Statesman of July 27, 1901, noted that “The adjoining owners agreeing to immediately build, and in conformity with the plans of the new structure, means practically an entire stone block for Idaho Street.”

According to the Idaho Architecture Project Website, the Union Block Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque-styled building. The sandstone came from Table Rock and the whole thing cost $35,000 to build.

Why was the building called the Union Block? The original owners were Union supporters who wanted to show that and thumb their collective noses to southern sympathizers who were still prevalent decades after the Civil War.

This was apparently a common tactic. Boise’s Union Block was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Joining it in that honor are at least eleven other Union Blocks around the country, including one in Iowa, two in Kansas, one in Maine, two in Michigan, one in North Dakota, one in New York, one in Ohio, one in Oregon, and one in Utah.

#unionblock #unionblockboise

The 125-foot-wide building in the center of these structures is actually the Union Block all by itself, as it says on the sandstone façade. It was designed in 1899 by architect John E. Tourellotte and completed in 1902. This was during a little building boom in Boise. As plans were announced for the Union Block adjacent property owners jumped on the bandwagon, matching facades on their buildings to that of the Union Block. The Idaho Statesman of July 27, 1901, noted that “The adjoining owners agreeing to immediately build, and in conformity with the plans of the new structure, means practically an entire stone block for Idaho Street.”

According to the Idaho Architecture Project Website, the Union Block Building is a Richardsonian Romanesque-styled building. The sandstone came from Table Rock and the whole thing cost $35,000 to build.

Why was the building called the Union Block? The original owners were Union supporters who wanted to show that and thumb their collective noses to southern sympathizers who were still prevalent decades after the Civil War.

This was apparently a common tactic. Boise’s Union Block was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. Joining it in that honor are at least eleven other Union Blocks around the country, including one in Iowa, two in Kansas, one in Maine, two in Michigan, one in North Dakota, one in New York, one in Ohio, one in Oregon, and one in Utah.

#unionblock #unionblockboise

Published on April 15, 2019 04:00

April 14, 2019

Moving American Falls

Power County, in southern Idaho, is named for the electricity generating facilities at the American Falls Dam. The dam is vitally important to the county. In fact, it is so important that the entire town of American Falls was moved to higher ground to accommodate the American Falls Reservoir.

Moving a town is a big job. It took about 18 months, starting in 1925, and wasn't complete until 1927.

Individual houses were moved by truck. Larger buildings were put on rollers and pulled along a few inches at a time. The Methodist church was taken down brick by brick and reconstructed with the rest of the town on the hill above the river. The Lutheran church was moved in one piece. In the middle of the move parishioners simply propped a ladder up against the building, climbed in, and held services in the middle of the street.

When the reservoir began to fill, the only thing left of the old town of American Falls was a cement grain elevator, abandoned foundations, and a grid of roads and sidewalks. You can still see the lonely old grain elevator sticking up like a tombstone for the town when the reservoir is low.

One other thing lost as a result of the dam project--the waterfall that gave the town its name. The 25-foot American Falls of the Snake River is now a part of history.

#americanfalls The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

Moving a town is a big job. It took about 18 months, starting in 1925, and wasn't complete until 1927.

Individual houses were moved by truck. Larger buildings were put on rollers and pulled along a few inches at a time. The Methodist church was taken down brick by brick and reconstructed with the rest of the town on the hill above the river. The Lutheran church was moved in one piece. In the middle of the move parishioners simply propped a ladder up against the building, climbed in, and held services in the middle of the street.

When the reservoir began to fill, the only thing left of the old town of American Falls was a cement grain elevator, abandoned foundations, and a grid of roads and sidewalks. You can still see the lonely old grain elevator sticking up like a tombstone for the town when the reservoir is low.

One other thing lost as a result of the dam project--the waterfall that gave the town its name. The 25-foot American Falls of the Snake River is now a part of history.

#americanfalls

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive, is of a two-story cement block building being moved to higher ground in 1925.

Published on April 14, 2019 04:00

April 13, 2019

Those Inverted Hoof Prints

Rangers at Malad Gorge State Park found a couple of sets of horse hoof prints in the park in 1990. That made a little news. Why? The hoof prints are estimated to be about a million years old.

In fact, the prints were rediscovered. A ranger was giving an interpretive program about the park when sisters Peggy Bennett Smith and Grace Bennett Goodlin interrupted to tell about a cave near the bottom of the gorge that they knew about. Smith, who lived in Hawaii, and Goodlin, visiting from Texas, had grown up nearby on their grandfather S.W. Ritchie’s ranch. As girls they had spent time fishing in the gorge and had seen the cave. (Deseret News, December 23, 1990)

Fossilized tracks of ancient animals are fairly common around the world. The ones at Malad Gorge may be unique. Rather than a depression in what was once mud, these prints were hoof-shaped mounds on the roof of the cave, almost as if you were looking at the bottom of the hoof plunging through the rock.

William (Bill) Akersten, PhD, then the curator of the Idaho Museum of Natural History studied the tracks and told how they were likely formed. There was wet sand or mud on top of an old lava flow when several horses came galloping along leaving hoof prints behind them. Speculating what they might have been running from a million years hence is just guesswork, but their existence proves that an active lava flow soon poured across the sand and the depressions left by the horses. At some point erosion from the nearby Malad River probably washed out the softer remnants of the ancient sand leaving behind a three-foot cave with hoof prints protruding from its ceiling.

The prints are about the size a modern horse might make. Though the animals that made them may have been distantly related, the prints were not made by the famous Hagerman Horse, fossils of which were found just a few miles away. The Hagerman Horse was smaller and lived about 2.5 million years earlier.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

In fact, the prints were rediscovered. A ranger was giving an interpretive program about the park when sisters Peggy Bennett Smith and Grace Bennett Goodlin interrupted to tell about a cave near the bottom of the gorge that they knew about. Smith, who lived in Hawaii, and Goodlin, visiting from Texas, had grown up nearby on their grandfather S.W. Ritchie’s ranch. As girls they had spent time fishing in the gorge and had seen the cave. (Deseret News, December 23, 1990)

Fossilized tracks of ancient animals are fairly common around the world. The ones at Malad Gorge may be unique. Rather than a depression in what was once mud, these prints were hoof-shaped mounds on the roof of the cave, almost as if you were looking at the bottom of the hoof plunging through the rock.

William (Bill) Akersten, PhD, then the curator of the Idaho Museum of Natural History studied the tracks and told how they were likely formed. There was wet sand or mud on top of an old lava flow when several horses came galloping along leaving hoof prints behind them. Speculating what they might have been running from a million years hence is just guesswork, but their existence proves that an active lava flow soon poured across the sand and the depressions left by the horses. At some point erosion from the nearby Malad River probably washed out the softer remnants of the ancient sand leaving behind a three-foot cave with hoof prints protruding from its ceiling.

The prints are about the size a modern horse might make. Though the animals that made them may have been distantly related, the prints were not made by the famous Hagerman Horse, fossils of which were found just a few miles away. The Hagerman Horse was smaller and lived about 2.5 million years earlier.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Somewhere near the bottom of Malad Gorge is the hoof print cave. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation.

Published on April 13, 2019 04:00

April 12, 2019

Idaho's Lost Counties

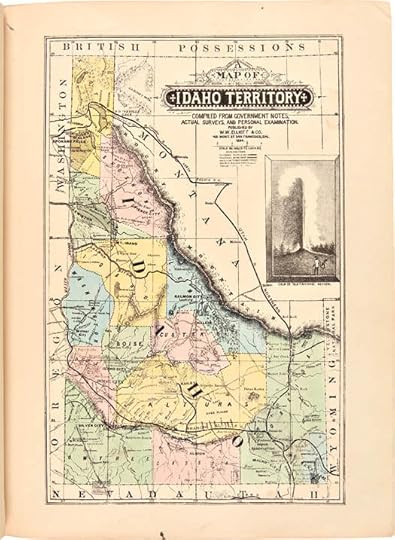

Idaho has 44 counties, ranging in size from 8,485-square-mile Idaho County, to Payette County, which is 408 square miles. But it hasn’t always been that way. County boundaries and the names of counties changed quite a lot over the years.

The original Idaho Territory included what we now call Montana and most of present-day Wyoming in 1863. By 1864 the Territory began to resemble the shape of the state we know today, and had 14 counties.

Those enormous counties got smaller as population grew and the need for government closer to home grew with it. Once a county was named, that name tended to stick, even through shrinkage. We lost only two names in the shuffle, Alturas and Logan.

Alturas was a county from February 4, 1864 to March 5, 1895. It was a huge county, bigger than the states of New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware combined. Elmore County and Logan County were carved out of Alturas in 1889 by the Idaho Legislature. But what the legislature giveth, it can also take away. In 1895 Logan and Alturas were combined to become Blaine County. Then just a couple of weeks later, the legislature sliced off a sizable piece of that to create Lincoln County.

#idahocounties

The original Idaho Territory included what we now call Montana and most of present-day Wyoming in 1863. By 1864 the Territory began to resemble the shape of the state we know today, and had 14 counties.

Those enormous counties got smaller as population grew and the need for government closer to home grew with it. Once a county was named, that name tended to stick, even through shrinkage. We lost only two names in the shuffle, Alturas and Logan.

Alturas was a county from February 4, 1864 to March 5, 1895. It was a huge county, bigger than the states of New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware combined. Elmore County and Logan County were carved out of Alturas in 1889 by the Idaho Legislature. But what the legislature giveth, it can also take away. In 1895 Logan and Alturas were combined to become Blaine County. Then just a couple of weeks later, the legislature sliced off a sizable piece of that to create Lincoln County.

#idahocounties

Published on April 12, 2019 09:00

April 11, 2019

Misspellings in Idaho History

Misspellings in Idaho History

Things get misspelled all the time. If you don’t believe that, you’re clearly not on Facebook. I’ve begun collecting a few misspellings that have had an impact on Idaho history. My hope is that readers will share some things they’ve noticed, such as:

Hagerman

Shoshoni Indians traditionally wintered here and speared salmon at Lower Salmon Falls. It became a stage station on the Oregon Trail, and eventually had enough residents that a couple of men applied for a post office. The men were Stanley Hegeman (or Hageman—I’ve seen it both ways) and Jack Hess. They wanted to call the place Hess, but postal officials nixed it because there was already a Hess, Idaho. There isn’t one now, and I’ve found no information about where Hess was. Someone will probably come to my rescue.

Naturally, since Hess was taken, they tried for Hageman (or Hegeman). Postal officials blessed that one, but misspelled the name as Hagerman, perhaps because of poor penmanship on the part of the applicants.

Potatoe

You remember Dan Quayle, right? He was the vice president who infamously corrected the spelling of Idaho’s famous tuber as “potatoe” in front of a group of kids on June 15, 1992. That moment is preserved for… as long as potatoes can be preserved, at the Idaho Potato Museum in Blackfoot. A California DJ asked Quayle to autograph a potato for him, all in good fun. Somehow the museum ended up with it.

Cariboo

Caribou County is named for Jesse “Cariboo Jack” Fairchild who was, in turn, nicknamed such because he had taken part in the gold rush in the Cariboo region of British Columbia in 1860. There are a lot of things around Soda Springs named after Cariboo Jack, including the ghost town of Caribou City, and the Caribou Mountains. Fairchild was born in Canada. What isn’t exactly clear is why the Cariboo region of British Columbia is spelled that way. Canadians don’t generally spell caribou differently. In any case Jack’s nickname became Caribou when it was attached to various sites in Caribou County, the last county created in Idaho.

Kansas

This one is outrageous. The Treaty of Fort Bridger was, among other things, meant to preserve the right of the Bannock Tribe to harvest camas bulbs on Camas Prairie near present-day Fairfield. Unfortunately, Camas Prairie was written as Kansas Prairie in the treaty. Using that flimsy excuse white settlers let their cattle and hogs trample and root around the traditional Bannock gathering site, devastating the camas fields, and leading to the Bannock War of 1878.

Spelling matters, kids.

Things get misspelled all the time. If you don’t believe that, you’re clearly not on Facebook. I’ve begun collecting a few misspellings that have had an impact on Idaho history. My hope is that readers will share some things they’ve noticed, such as:

Hagerman

Shoshoni Indians traditionally wintered here and speared salmon at Lower Salmon Falls. It became a stage station on the Oregon Trail, and eventually had enough residents that a couple of men applied for a post office. The men were Stanley Hegeman (or Hageman—I’ve seen it both ways) and Jack Hess. They wanted to call the place Hess, but postal officials nixed it because there was already a Hess, Idaho. There isn’t one now, and I’ve found no information about where Hess was. Someone will probably come to my rescue.

Naturally, since Hess was taken, they tried for Hageman (or Hegeman). Postal officials blessed that one, but misspelled the name as Hagerman, perhaps because of poor penmanship on the part of the applicants.

Potatoe

You remember Dan Quayle, right? He was the vice president who infamously corrected the spelling of Idaho’s famous tuber as “potatoe” in front of a group of kids on June 15, 1992. That moment is preserved for… as long as potatoes can be preserved, at the Idaho Potato Museum in Blackfoot. A California DJ asked Quayle to autograph a potato for him, all in good fun. Somehow the museum ended up with it.

Cariboo

Caribou County is named for Jesse “Cariboo Jack” Fairchild who was, in turn, nicknamed such because he had taken part in the gold rush in the Cariboo region of British Columbia in 1860. There are a lot of things around Soda Springs named after Cariboo Jack, including the ghost town of Caribou City, and the Caribou Mountains. Fairchild was born in Canada. What isn’t exactly clear is why the Cariboo region of British Columbia is spelled that way. Canadians don’t generally spell caribou differently. In any case Jack’s nickname became Caribou when it was attached to various sites in Caribou County, the last county created in Idaho.

Kansas

This one is outrageous. The Treaty of Fort Bridger was, among other things, meant to preserve the right of the Bannock Tribe to harvest camas bulbs on Camas Prairie near present-day Fairfield. Unfortunately, Camas Prairie was written as Kansas Prairie in the treaty. Using that flimsy excuse white settlers let their cattle and hogs trample and root around the traditional Bannock gathering site, devastating the camas fields, and leading to the Bannock War of 1878.

Spelling matters, kids.

Published on April 11, 2019 04:00

April 10, 2019

Charles Lindbergh Drops in

There was no bigger celebrity in 1927 than Charles Lindbergh. On May 27 of that year the 25-year-old US Mail pilot had landed his single-engine plane, the Spirit of St. Louis in Paris to complete the first solo flight across the Atlantic. Then he took a real trip. The Daniel Guggenheim Fund sponsored a three-month flying tour that would take him to 48 states, where he would visit 92 cities and give 147 speeches.

Lindbergh landed in Boise on September 4 and was greeted by a crowd of 40,000 people. This picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows, left to right, Leo J. Falk, Gov. H.C. Baldridge, and Boise Mayor Walter F. Hanson with Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Lewis is in the background.

The Idaho Statesman described Lindy’s departure thusly: “Lindy made a graceful take-off, just as he had landed the day before. He circled over the city, then headed northeast over the hills, rising higher and higher into the clouds until the Spirit of St. Louis appeared a little speck in the sky. Lindy was gone.”

It was his only stop in Idaho on the tour, but folks in the northern part of the state had a chance to see him and his famous plane land in Spokane on September 12.

#luckylindy #lindberghboise #lindbergh

Lindbergh landed in Boise on September 4 and was greeted by a crowd of 40,000 people. This picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, shows, left to right, Leo J. Falk, Gov. H.C. Baldridge, and Boise Mayor Walter F. Hanson with Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Lewis is in the background.

The Idaho Statesman described Lindy’s departure thusly: “Lindy made a graceful take-off, just as he had landed the day before. He circled over the city, then headed northeast over the hills, rising higher and higher into the clouds until the Spirit of St. Louis appeared a little speck in the sky. Lindy was gone.”

It was his only stop in Idaho on the tour, but folks in the northern part of the state had a chance to see him and his famous plane land in Spokane on September 12.

#luckylindy #lindberghboise #lindbergh

Published on April 10, 2019 04:00