Rick Just's Blog, page 203

March 30, 2019

That Idaho Shape

So, every state has a unique shape. Even Wyoming and Colorado are different-sized rectangles. By the way, what’s with those two? It’s like map makers just got bored at the end of the day and drew four lines with their T-squares. Even Kansas, as one-dimensional as a sheet of paper, has a little oops in the upper right hand corner where Missouri slouches into it.

But I digress.

The shape of Idaho just wants to be noticed. It has that gnome-sitting-in-a-chair thing going for it. Its face stares into Montana while Montana, rudely, stares into Idaho’s belly. It’s one of a handful of states that extends more vertically than horizontally, as if it is always in ascension.

And it has a legend.

In 1863, when Idaho became a territory, its boundaries included most of Wyoming, and all of Montana. That didn't last long, though. Congress carved Montana out of Idaho Territory in May of 1864, choosing the Bitterroot Mountain Range as the main border between the two territories.

Somehow, though, a legend grew up that the boundary was the result of a surveying error. According to this tale, the border was supposed to follow the Continental Divide all the way to Canada. Idaho would have included Missoula, Butte, and all of Montana west of the Rockies--a nice little piece of land.

The story goes that the surveyors were drunk, or they had been paid off by agents from Montana who wanted a bigger territory. It's a good story, but it isn't true. In fact, the boundary between Montana and Idaho wasn't even officially surveyed until fourteen years after Idaho statehood. The states simply got along knowing that the border generally followed the crest of the Bitterroots, as designated by the U.S. Congress.

In the years leading up to statehood; there was a lot of haggling and political maneuvering over where Idaho's borders should be. But drunken surveying crews did not play a part in shaping the state.

One footnote. I’m told the boundary legend tale came about because surveyors had a habit of dropping their empty refreshment bottles in the hole when they placed survey markers.

But I digress.

The shape of Idaho just wants to be noticed. It has that gnome-sitting-in-a-chair thing going for it. Its face stares into Montana while Montana, rudely, stares into Idaho’s belly. It’s one of a handful of states that extends more vertically than horizontally, as if it is always in ascension.

And it has a legend.

In 1863, when Idaho became a territory, its boundaries included most of Wyoming, and all of Montana. That didn't last long, though. Congress carved Montana out of Idaho Territory in May of 1864, choosing the Bitterroot Mountain Range as the main border between the two territories.

Somehow, though, a legend grew up that the boundary was the result of a surveying error. According to this tale, the border was supposed to follow the Continental Divide all the way to Canada. Idaho would have included Missoula, Butte, and all of Montana west of the Rockies--a nice little piece of land.

The story goes that the surveyors were drunk, or they had been paid off by agents from Montana who wanted a bigger territory. It's a good story, but it isn't true. In fact, the boundary between Montana and Idaho wasn't even officially surveyed until fourteen years after Idaho statehood. The states simply got along knowing that the border generally followed the crest of the Bitterroots, as designated by the U.S. Congress.

In the years leading up to statehood; there was a lot of haggling and political maneuvering over where Idaho's borders should be. But drunken surveying crews did not play a part in shaping the state.

One footnote. I’m told the boundary legend tale came about because surveyors had a habit of dropping their empty refreshment bottles in the hole when they placed survey markers.

Published on March 30, 2019 04:00

March 29, 2019

Mr. Television

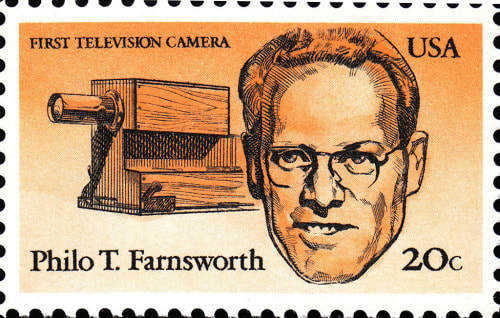

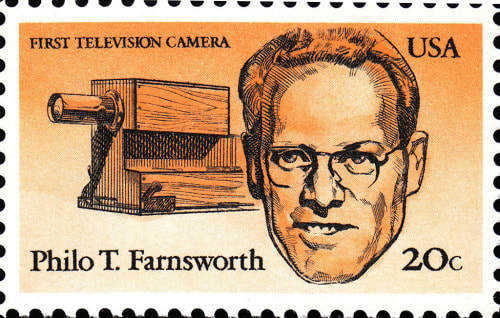

Today, a tip of the hat to the Idahoan who made "Game of Thrones” and "Gilligan's Island" possible.

When Philo T. Farnsworth appeared on the 1950s TV show, "I've Got a Secret," he leaned over and whispered his secret in the game show host's ear. When the secret was flashed on the screen for the audience and viewers at home, there was a lot of oohing and ahhing. Philo Taylor Farnsworth's secret was amazing. He had invented television. Perhaps even more amazing, he had done it when he was a high school student in Rigby, Idaho in 1922.

Farnsworth had recently heard radio broadcasts for the first time, and he was enchanted with the medium. But, wouldn't it be great if you could send pictures through the air, too? The young inventor sketched his idea for the cathode ray tube on a high school blackboard. That tube became the basis for modern television.

At the age of 20, Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic television image. In 1930, he received the first patent for television. The former Rigby High School student went on to invent the first simple electron microscope. He did pioneering work on radar, black light viewing, and the peaceful use of atomic energy.

In all, Philo T. Farnsworth held over 300 U.S. and foreign patents. In 1983 the inventor was honored with a postage stamp. He is one of only three Idahoans so honored.

You can visit the Farnsworth TV and Pioneer Museum in Rigby, if you’d like to learn more.

When Philo T. Farnsworth appeared on the 1950s TV show, "I've Got a Secret," he leaned over and whispered his secret in the game show host's ear. When the secret was flashed on the screen for the audience and viewers at home, there was a lot of oohing and ahhing. Philo Taylor Farnsworth's secret was amazing. He had invented television. Perhaps even more amazing, he had done it when he was a high school student in Rigby, Idaho in 1922.

Farnsworth had recently heard radio broadcasts for the first time, and he was enchanted with the medium. But, wouldn't it be great if you could send pictures through the air, too? The young inventor sketched his idea for the cathode ray tube on a high school blackboard. That tube became the basis for modern television.

At the age of 20, Farnsworth produced the first all-electronic television image. In 1930, he received the first patent for television. The former Rigby High School student went on to invent the first simple electron microscope. He did pioneering work on radar, black light viewing, and the peaceful use of atomic energy.

In all, Philo T. Farnsworth held over 300 U.S. and foreign patents. In 1983 the inventor was honored with a postage stamp. He is one of only three Idahoans so honored.

You can visit the Farnsworth TV and Pioneer Museum in Rigby, if you’d like to learn more.

Published on March 29, 2019 04:00

March 28, 2019

Doc Roach

Not many public servants reach a measure of fame, even in their home towns.

W.F

. (Doc) Roach did. Roach started his career with the Boise Fire Department in 1910 when fire engines were pulled by horses, and didn’t retire until 1965. The top picture, taken in 1912, shows him on the left, seated on the fire wagon at Boise Fire Station Number 2 in the North End.

Roach served five years as one of Boise’s first motorcycle police officers, but served the rest of his 54-year career with Boise Fire. Roach was a dispatcher for the fire department from 1922 to 1947, when he became the city’s fire marshal, a position he stayed in until his retirement.

Roach was well known in the city because of his efforts at fire prevention, including public campaigns. In the bottom photo Doc Roach stands with the winner of the 1957 “Miss Sparky” competition that was held as part of Fire Prevention Week. Sarah Jane Benson was “Miss Sparky” that year.

Doc Roach shot and collected hundreds of photos over his career, creating a precious resource for historians. The two featured photos are from the Doc Roach Fire Collection Courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Roach served five years as one of Boise’s first motorcycle police officers, but served the rest of his 54-year career with Boise Fire. Roach was a dispatcher for the fire department from 1922 to 1947, when he became the city’s fire marshal, a position he stayed in until his retirement.

Roach was well known in the city because of his efforts at fire prevention, including public campaigns. In the bottom photo Doc Roach stands with the winner of the 1957 “Miss Sparky” competition that was held as part of Fire Prevention Week. Sarah Jane Benson was “Miss Sparky” that year.

Doc Roach shot and collected hundreds of photos over his career, creating a precious resource for historians. The two featured photos are from the Doc Roach Fire Collection Courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Published on March 28, 2019 04:00

March 27, 2019

Dean Oliver

Kids, stay in school. You need that diploma. Now, with that out of the way, I can go on with the story.

Dean Oliver grew up dirt poor in Idaho. When Dean was 11, in 1940, his father was killed in an airplane crash while hunting coyotes with a partner over the Arco desert. That left Dean’s mom struggling to feed seven kids. So, Oliver dropped out of school during ninth grade in Nampa to help supplement his mother’s income and, frankly, because he couldn’t stop thinking about being a cowboy. It seemed like an impossible dream for a frail kid with a speech defect that caused him to pronounce rodeo and rope as wodeo and wope.

He couldn’t pronounce those words the way they were supposed to sound, but he could rodeo and he could rope. He first got his inspiration when he snuck into the Snake River Stampede and watched a little guy with glasses walk away with $300 in the roping competition. Starting with a beat-up mare he bought for $50, Oliver started to learn how to rope. He got pretty good at it.

He won his first professional roping competition in Jerome, Idaho, in 1952, and just kept on winning. He was the proclaimed the world champion calf roper in 1955. The frail kid from Idaho, by that time, weighed 200 pounds and stood at six three. Nobody cared how he pronounced rodeo.

Dean Oliver still holds the record for most world titles in calf roping with eight, including winning five straight from 1960-1964. He was crowned all-around world champion cowboy three years in a row, 1963-1965.

The picture is a page from the January 28th, 1966, edition of the Idaho Statesman. The article featured numerous pictures of Oliver and his family, including the one at top left of his two-year-old daughter Nikki wearing his championship hat and buckle, and sitting on his championship saddle.

Dean Oliver grew up dirt poor in Idaho. When Dean was 11, in 1940, his father was killed in an airplane crash while hunting coyotes with a partner over the Arco desert. That left Dean’s mom struggling to feed seven kids. So, Oliver dropped out of school during ninth grade in Nampa to help supplement his mother’s income and, frankly, because he couldn’t stop thinking about being a cowboy. It seemed like an impossible dream for a frail kid with a speech defect that caused him to pronounce rodeo and rope as wodeo and wope.

He couldn’t pronounce those words the way they were supposed to sound, but he could rodeo and he could rope. He first got his inspiration when he snuck into the Snake River Stampede and watched a little guy with glasses walk away with $300 in the roping competition. Starting with a beat-up mare he bought for $50, Oliver started to learn how to rope. He got pretty good at it.

He won his first professional roping competition in Jerome, Idaho, in 1952, and just kept on winning. He was the proclaimed the world champion calf roper in 1955. The frail kid from Idaho, by that time, weighed 200 pounds and stood at six three. Nobody cared how he pronounced rodeo.

Dean Oliver still holds the record for most world titles in calf roping with eight, including winning five straight from 1960-1964. He was crowned all-around world champion cowboy three years in a row, 1963-1965.

The picture is a page from the January 28th, 1966, edition of the Idaho Statesman. The article featured numerous pictures of Oliver and his family, including the one at top left of his two-year-old daughter Nikki wearing his championship hat and buckle, and sitting on his championship saddle.

Published on March 27, 2019 04:00

March 26, 2019

Chicken Out Ridge

I’ve been to many places in Idaho, and still have a lifetime of it to see. One place I likely won’t visit up close and personal, is the top of Mt. Borah, Idaho’s tallest peak. I’ve given some thought to climbing it. In climbing vernacular, it’s a “walk up.” Tempting. But there’s that one spot that’s scary enough to have its own name. That’s Chicken Out Ridge.

I’ve had many friends climb Borah. They’ve all assured me that there’s nothing to it. Well, except for the one spot that’s a little hairy.

Uh huh. This falls into the same category as those times when my wife tells me, “Try it. It isn’t hot.”

I am not a fan of declivities, and I HAVE seen the pictures, one of which is included with this post so that you can be the judge. This is the ridge running up toward the top, with a well-worn trail beckoning, though it is not a photo of the “hairy” part.

Mount Borah doesn’t look like much from the highway, which has always been my vantage point. From other angles, it looks quite spectacular. It is one of only three peaks in Idaho with more than 5,000 feet of prominence, the other two being He Devil and Diamond Peak.

As a walk-up, it was likely climbed by indigenous peoples many years ago, but the first recorded climb was by a USGS surveyor, T.M. Bannon in 1912. There are more difficult ascents you can take if you’re an experienced climber and the Chicken Out Ridge route seems, uh, pedestrian. Go for it. Send me a postcard.

#chickenoutridge #mountborah

I’ve had many friends climb Borah. They’ve all assured me that there’s nothing to it. Well, except for the one spot that’s a little hairy.

Uh huh. This falls into the same category as those times when my wife tells me, “Try it. It isn’t hot.”

I am not a fan of declivities, and I HAVE seen the pictures, one of which is included with this post so that you can be the judge. This is the ridge running up toward the top, with a well-worn trail beckoning, though it is not a photo of the “hairy” part.

Mount Borah doesn’t look like much from the highway, which has always been my vantage point. From other angles, it looks quite spectacular. It is one of only three peaks in Idaho with more than 5,000 feet of prominence, the other two being He Devil and Diamond Peak.

As a walk-up, it was likely climbed by indigenous peoples many years ago, but the first recorded climb was by a USGS surveyor, T.M. Bannon in 1912. There are more difficult ascents you can take if you’re an experienced climber and the Chicken Out Ridge route seems, uh, pedestrian. Go for it. Send me a postcard.

#chickenoutridge #mountborah

Published on March 26, 2019 04:00

March 25, 2019

Bud the Motoring Dog

The story starts on May 23, 1903, in San Francisco when Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson and Sewall Crocker climbed into the front seat a of second-hand cherry-red Winton touring car and set out for New York City. The trip started as a $50 bar bet. Jackson, who had little experience with automobiles, was challenged on his statement that an automobile could make it coast-to-coast in 90 days. He took the bet, bought the car, and hired Crocker to go along with him as a driver and mechanic.

There were no road maps back then. There were barely roads. Only about 150 miles of pavement existed in the country, all of that within city limits.

The old saw about someone having more money than sense might have applied to Jackson. This was a spur-of-the-moment adventure that should have ended in disaster. Instead, it became a string of small disasters, flat tires, broken parts, and gasoline shortages, that piled up to make a success.

I found only one mention of the trip in an Idaho newspaper while it was taking place. There was a brief story on the front page of the Montpelier Examiner on Friday, June, 19, 1903. Headlined “A Curiosity for this City,” the short piece focused more on the fact the Winton was the first automobile to appear in Montpelier than the trip itself.

Nelson didn’t start getting much newspaper coverage until he had made it a little further east. By the time he hit Chicago on July 17, he got a grand reception from city officials. Publicity for the stunt built with a stop in Cleveland, where the Winton had been built. Outside of Buffalo all three riders were thrown out of the car in a little accident, but none were hurt.

Three? Nelson, of course, and Crocker… And Bud. It seems that when the humans left Caldwell, Idaho on June 12, Nelson discovered he’d left his coat behind at the hotel. They went back to get it and encountered a man with a bull dog along the way. The man suggested that they really needed a mascot for their trip. Nelson had been looking for one, so paid the man $15 and got Bud to climb aboard.

Bud became the star of the trip because, well, dog. And dog with driving goggles. The dust could be irritating on the eyes when you were speeding along at 15 or 20 MPH with no windshield. Bud didn’t seem to mind the goggles and he loved riding in the car.

The two guys and a dog rolled into New York City at 4:30 in the morning Sunday, July 26, 63 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes after leaving San Francisco. Nelson reportedly never did bother to collect on his bet. He spent $8,000 making himself and his dog famous. A 1903 Winton, along with a depiction of Nelson and Bud the dog tells the story of the first cross-county auto trip at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

Ken Burns did a series for PBS on the adventure, called Horatio’s Drive in 2003, which can found on YouTube.

There were no road maps back then. There were barely roads. Only about 150 miles of pavement existed in the country, all of that within city limits.

The old saw about someone having more money than sense might have applied to Jackson. This was a spur-of-the-moment adventure that should have ended in disaster. Instead, it became a string of small disasters, flat tires, broken parts, and gasoline shortages, that piled up to make a success.

I found only one mention of the trip in an Idaho newspaper while it was taking place. There was a brief story on the front page of the Montpelier Examiner on Friday, June, 19, 1903. Headlined “A Curiosity for this City,” the short piece focused more on the fact the Winton was the first automobile to appear in Montpelier than the trip itself.

Nelson didn’t start getting much newspaper coverage until he had made it a little further east. By the time he hit Chicago on July 17, he got a grand reception from city officials. Publicity for the stunt built with a stop in Cleveland, where the Winton had been built. Outside of Buffalo all three riders were thrown out of the car in a little accident, but none were hurt.

Three? Nelson, of course, and Crocker… And Bud. It seems that when the humans left Caldwell, Idaho on June 12, Nelson discovered he’d left his coat behind at the hotel. They went back to get it and encountered a man with a bull dog along the way. The man suggested that they really needed a mascot for their trip. Nelson had been looking for one, so paid the man $15 and got Bud to climb aboard.

Bud became the star of the trip because, well, dog. And dog with driving goggles. The dust could be irritating on the eyes when you were speeding along at 15 or 20 MPH with no windshield. Bud didn’t seem to mind the goggles and he loved riding in the car.

The two guys and a dog rolled into New York City at 4:30 in the morning Sunday, July 26, 63 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes after leaving San Francisco. Nelson reportedly never did bother to collect on his bet. He spent $8,000 making himself and his dog famous. A 1903 Winton, along with a depiction of Nelson and Bud the dog tells the story of the first cross-county auto trip at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC.

Ken Burns did a series for PBS on the adventure, called Horatio’s Drive in 2003, which can found on YouTube.

Published on March 25, 2019 04:00

March 24, 2019

Fords Made in Boise

What town comes to mind when you think automobile manufacturing? Detroit? Dearborn? Boise?

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, is H.H. and M.B. Bryant’s Ford dealership in 1917. It was located at 1602 Main. But it wasn’t just an ordinary dealership. They put together Fords there for a time in 1914. H.H. was married to Henry Ford’s sister, so had a bit of an in.

Ford was famous for revolutionizing the industry with the assembly line process, beginning with the 1914 Model T. It’s not clear what advantage shipping pieces and parts to Boise for assembly had for Mr. Bryant, but he did put together cars in the capital city for a while.

Mr. Mason, a salesman for Bryant Motor Company. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Mr. Mason, a salesman for Bryant Motor Company. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, is H.H. and M.B. Bryant’s Ford dealership in 1917. It was located at 1602 Main. But it wasn’t just an ordinary dealership. They put together Fords there for a time in 1914. H.H. was married to Henry Ford’s sister, so had a bit of an in.

Ford was famous for revolutionizing the industry with the assembly line process, beginning with the 1914 Model T. It’s not clear what advantage shipping pieces and parts to Boise for assembly had for Mr. Bryant, but he did put together cars in the capital city for a while.

Mr. Mason, a salesman for Bryant Motor Company. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Mr. Mason, a salesman for Bryant Motor Company. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on March 24, 2019 04:00

March 23, 2019

Idaho and Andy Griffith

Okay, I’m vying for the least important Speaking of Idaho post of all time with this one. Even so, I may be able to quell an argument that seems to be bubbling between Andy Griffith show fans.

Mayberry is not in Idaho. That won’t settle the argument, though. Mayberry is also not in North Carolina, the state in which the fictional town was said to be. Mount Airy, Andy Griffith’s boyhood home, embraces its role as “Mayberry,” and has as good a claim as any town.

The argument is about a map that could be seen on the wall in Andy’s office. Legend has it that the map, perhaps meant to be a county or city map, was actually a map of Idaho hung upside down. True. And false. A map of Idaho did hang upside down in the office for at least one, and possibly several episodes, but not for the whole series. Maps seemed to be a joke with the sets people. Nevada was also hung from its feet, North Carolina was displayed, and most often the map was of Cincinnati.

The old publicity photo below clearly shows your favorite state map flying in distress mode on the wall over Don Knotts’ shoulder.

The shape of Idaho is just another thing to love about the state. Pity the poor folks from Colorado for their lack of recognizable state lapel pins.

Mayberry is not in Idaho. That won’t settle the argument, though. Mayberry is also not in North Carolina, the state in which the fictional town was said to be. Mount Airy, Andy Griffith’s boyhood home, embraces its role as “Mayberry,” and has as good a claim as any town.

The argument is about a map that could be seen on the wall in Andy’s office. Legend has it that the map, perhaps meant to be a county or city map, was actually a map of Idaho hung upside down. True. And false. A map of Idaho did hang upside down in the office for at least one, and possibly several episodes, but not for the whole series. Maps seemed to be a joke with the sets people. Nevada was also hung from its feet, North Carolina was displayed, and most often the map was of Cincinnati.

The old publicity photo below clearly shows your favorite state map flying in distress mode on the wall over Don Knotts’ shoulder.

The shape of Idaho is just another thing to love about the state. Pity the poor folks from Colorado for their lack of recognizable state lapel pins.

Published on March 23, 2019 04:00

March 22, 2019

York

Idaho was not involved in the Civil War, though vestiges of that sad chapter of American history can be found in towns and places named by proponents of one side or another. Atlanta and Yankee Fork are two examples.

But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history, nevertheless.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

#slavery

But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history, nevertheless.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

#slavery

Published on March 22, 2019 04:00

March 21, 2019

A Silver City Theater

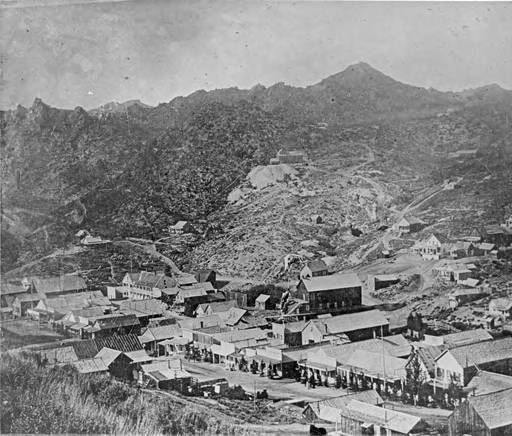

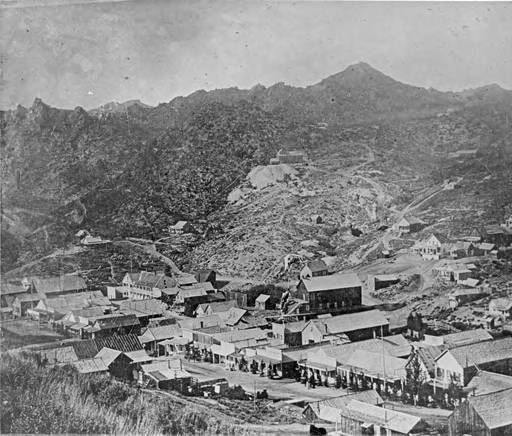

What turns a group of buildings thrown up to provide essentials for miners into a community? In the 1860s Silver City had billiard halls, horse races, saloons, gambling halls, a red-light district, and a fledgling library. But what it really needed, according the Owyhee Avalanche was a theater. The May 5, 1866 edition of the newspaper carried an editorial that said in part, “Parties who have the cash to spare could hardly use it to more certain advantages than in erecting a theater building of neat finish and reasonable dimensions. In the dullest times, theatrical and minstrel performances are well patronized. We verily believe that if one could be put in operation now with fair talent and creditable management, it would be crowded nightly.”

By 1868, Silver City must have been a fine community, indeed, because it had TWO theaters. John McGinely, one of the theater owners, promoted an early production by offering to give a gold ring worth $10 to the person in the audience who could come up with the most original conundrum (a riddle whose answer is a pun). Sadly, the winning riddle did not survive the ages.

The newspaper whose editorial plea may have sparked theater in Silver City, was not always a fan of the productions. On May 21, 1870, the paper gave one troupe a slap:

“The Carter Troupe have ‘folded their tents like the Arabs and silently stole away.’ Good riddance. Although his playing was passable, yet we couldn’t tolerate so much beggarly meanness as was concentrated in the person of J.W. Carter. We gave him a complementary notice last week which he didn’t seem to appreciate. Of all the contemptible catchpennies that ever afflicted our Territory he is the chief; of all the miserly exotics that ever visited Idaho he is conspicuous; of all the pitiful paltry scrubs that we ever saw, he caps the climax.”

Some productions had moved to Champion Hall by 1873, a new theater facility with seating for perhaps 150. On opening night the audience got a little scare when one of the supports for the building settled loudly and abruptly. It may have been an ominous sign. Silver City was attracting fewer professional productions and many of the amateurs who had performed had moved away. By 1874 the Owyhee Avalanche reported that “The old Silver City Theatre was torn down and moved to the Mahogany mine this week, where it will be rebuilt for an engine-house, etc.”

Things happened fast in a boom town. For the most part, the heyday of theater came and went in a period of about six years in Silver City. Not very long, but long enough for the newspaper to think of one of the theaters as “old.”

The photo of Silver City in 1891 is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

By 1868, Silver City must have been a fine community, indeed, because it had TWO theaters. John McGinely, one of the theater owners, promoted an early production by offering to give a gold ring worth $10 to the person in the audience who could come up with the most original conundrum (a riddle whose answer is a pun). Sadly, the winning riddle did not survive the ages.

The newspaper whose editorial plea may have sparked theater in Silver City, was not always a fan of the productions. On May 21, 1870, the paper gave one troupe a slap:

“The Carter Troupe have ‘folded their tents like the Arabs and silently stole away.’ Good riddance. Although his playing was passable, yet we couldn’t tolerate so much beggarly meanness as was concentrated in the person of J.W. Carter. We gave him a complementary notice last week which he didn’t seem to appreciate. Of all the contemptible catchpennies that ever afflicted our Territory he is the chief; of all the miserly exotics that ever visited Idaho he is conspicuous; of all the pitiful paltry scrubs that we ever saw, he caps the climax.”

Some productions had moved to Champion Hall by 1873, a new theater facility with seating for perhaps 150. On opening night the audience got a little scare when one of the supports for the building settled loudly and abruptly. It may have been an ominous sign. Silver City was attracting fewer professional productions and many of the amateurs who had performed had moved away. By 1874 the Owyhee Avalanche reported that “The old Silver City Theatre was torn down and moved to the Mahogany mine this week, where it will be rebuilt for an engine-house, etc.”

Things happened fast in a boom town. For the most part, the heyday of theater came and went in a period of about six years in Silver City. Not very long, but long enough for the newspaper to think of one of the theaters as “old.”

The photo of Silver City in 1891 is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on March 21, 2019 04:00