Rick Just's Blog, page 205

March 10, 2019

Early Automobiles

Automobiles were a wonder when the first came out, sure to attract a crowd in any Idaho city, including Idaho City, where according to the Idaho City World, in July of 1904, “Mr. and Mrs. F.L. Sweaney surprised the natives yesterday afternoon without previous warning, in an automobile.” It was the first horseless carriage ever seen there.

That was nothing, though, because the Hailey News-Miner reported the first automobile to be seen on the streets in Hailey more than a year earlier, in June 1903. The paper noted that “A Hailey lad was on the race track when the auto passed. On first seeing it approach he shouted out: ‘Here comes a runaway with the tongue out!’”

By 1905, autos were common enough in the capital city that the Idaho Statesman noted the first one to be seized in a legal process.

In 1907, that same paper told about the first car to make a long, arduous journey from Boise to Horseshoe Bend. It took the car, a White Steamer, an hour and a half to get to Pearl on the way to Horsehoe Bend. On the way back they did the trip from Pearl in an hour and 20 minutes, “the car behaving so well that at no time were they compelled to stop or do anything to the machine.”

That same year the first automobile reached Silver City, giving citizens their first look at a “Buzz Wagon.” The Statesman reported that “Many young and older people here had never seen an automobile before, and there have been many visitors at Gardener’s barn to look it over.”

By 1909 cars were old hat. The Statesman ran a humorous piece about the inevitability of car ownership. “It will be recalled that the first automobile was purchased by a Boise ice man. That is in harmony with fixed conditions. Luxuries are always secured first by the wealthiest classes. Then a plumber broke in. He was logically next. The coal man was a trifle late, though third, but he purchased a machine that eclipsed all others in point of style and speed. The doctors began to purchase, followed by the undertakers, another natural sequence. A little later on the bankers bought, but they could not afford such swell turnouts as those who entered the field earlier. So it will go down the line. Somewhere, probably as a tailender, the newspaper man will get in.”

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

That was nothing, though, because the Hailey News-Miner reported the first automobile to be seen on the streets in Hailey more than a year earlier, in June 1903. The paper noted that “A Hailey lad was on the race track when the auto passed. On first seeing it approach he shouted out: ‘Here comes a runaway with the tongue out!’”

By 1905, autos were common enough in the capital city that the Idaho Statesman noted the first one to be seized in a legal process.

In 1907, that same paper told about the first car to make a long, arduous journey from Boise to Horseshoe Bend. It took the car, a White Steamer, an hour and a half to get to Pearl on the way to Horsehoe Bend. On the way back they did the trip from Pearl in an hour and 20 minutes, “the car behaving so well that at no time were they compelled to stop or do anything to the machine.”

That same year the first automobile reached Silver City, giving citizens their first look at a “Buzz Wagon.” The Statesman reported that “Many young and older people here had never seen an automobile before, and there have been many visitors at Gardener’s barn to look it over.”

By 1909 cars were old hat. The Statesman ran a humorous piece about the inevitability of car ownership. “It will be recalled that the first automobile was purchased by a Boise ice man. That is in harmony with fixed conditions. Luxuries are always secured first by the wealthiest classes. Then a plumber broke in. He was logically next. The coal man was a trifle late, though third, but he purchased a machine that eclipsed all others in point of style and speed. The doctors began to purchase, followed by the undertakers, another natural sequence. A little later on the bankers bought, but they could not afford such swell turnouts as those who entered the field earlier. So it will go down the line. Somewhere, probably as a tailender, the newspaper man will get in.”

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

The photo, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection, is of a Buick climbing Slaughterhouse Hill in Boise. The hill was a popular place to test the abilities of cars around 1910. It was, and perhaps still is if development hasn’t shaved it off, located a little north of the end of Harrison Boulevard.

Published on March 10, 2019 04:00

March 9, 2019

Harold Brighton

Famous men and women get all the ink. People who never did anything worthy of a history book should get an occasional mention. That’s my mission today as I tell you about Harold Brighton, a man famous only in Firth.

Harold was the town barber for many years, working out of a tiny one-chair shop on main street. You could sit in the leather seat—or on the board placed across the arms if you were a little kid—and stare into infinity as your image bounced forth and back between the big mirrors on facing walls. The marble shelves beneath the mirror behind Harold was like a barback, bottles of various tonics and smell-goods sparkling in their reflections.

Those waiting for their haircut spent their time in chairs borrowed from an abandoned theater. They could read comics or mild men’s magazines. Mostly they talked about weather and farming.

The thing Harold will always be remembered for was his nickel rebate. It happened to be a pair of my cousins, Charlie and Frank Just, who as rambunctious kids started the tradition. They were bouncing around one day under the control of no one, their dad likely down the street at the drugstore or talking with someone at the International Harvester dealership nearby.

With no adult supervision handy, Harold bribed the kids. He offered them each a nickel to go get an ice cream cone after their haircut, if they’d sit still and be quiet. That was the best deal they’d heard all day, so the brothers were good as gold.

Harold might have forgotten about the nickels, but the Just kids didn’t. They expected it the next time they came in for their $1 haircuts. Further, they spread the word about the sit-still bribe among all their friends. Harold was on the hook for ice cream nickels from then on.

The tradition became so expected that some parents tried giving Harold 95 cents instead of the posted price of one dollar. Harold wouldn’t have it. Haircuts were a buck. The nickel belonged to a kid who worked hard at sitting still.

Harold Brighton often said that he could have bought a Cadillac with all the nickels he gave away over the years.

When Harold closed up shop and retired, my son, Jarad, was just about ready for his first haircut. I talked Harold into opening up the shop one more time so I could get the picture below of Jarad’s first haircut, and Harold’s last. It’s one of many treasured memories I have of a man famous only in Firth.

Harold was the town barber for many years, working out of a tiny one-chair shop on main street. You could sit in the leather seat—or on the board placed across the arms if you were a little kid—and stare into infinity as your image bounced forth and back between the big mirrors on facing walls. The marble shelves beneath the mirror behind Harold was like a barback, bottles of various tonics and smell-goods sparkling in their reflections.

Those waiting for their haircut spent their time in chairs borrowed from an abandoned theater. They could read comics or mild men’s magazines. Mostly they talked about weather and farming.

The thing Harold will always be remembered for was his nickel rebate. It happened to be a pair of my cousins, Charlie and Frank Just, who as rambunctious kids started the tradition. They were bouncing around one day under the control of no one, their dad likely down the street at the drugstore or talking with someone at the International Harvester dealership nearby.

With no adult supervision handy, Harold bribed the kids. He offered them each a nickel to go get an ice cream cone after their haircut, if they’d sit still and be quiet. That was the best deal they’d heard all day, so the brothers were good as gold.

Harold might have forgotten about the nickels, but the Just kids didn’t. They expected it the next time they came in for their $1 haircuts. Further, they spread the word about the sit-still bribe among all their friends. Harold was on the hook for ice cream nickels from then on.

The tradition became so expected that some parents tried giving Harold 95 cents instead of the posted price of one dollar. Harold wouldn’t have it. Haircuts were a buck. The nickel belonged to a kid who worked hard at sitting still.

Harold Brighton often said that he could have bought a Cadillac with all the nickels he gave away over the years.

When Harold closed up shop and retired, my son, Jarad, was just about ready for his first haircut. I talked Harold into opening up the shop one more time so I could get the picture below of Jarad’s first haircut, and Harold’s last. It’s one of many treasured memories I have of a man famous only in Firth.

Published on March 09, 2019 04:00

March 8, 2019

Cassia Crossbills

The mountain bluebird is Idaho’s state bird. They are beautiful, though fairly common, creatures. They range from Alaska to Mexico and are found in every western state. But, what if there were a bird found only in Idaho? Would that bird knock the bluebird off its official perch?

Probably not. People love bluebirds. But there is a potential contender that may meet that only in Idaho test. American Ornithological Society publishes and annual checklist for birders. There are often a few changes on that list, and this year one of those changes is about the South Hills or Cassia Crossbill.

Crossbills are birds that look like they’ve been in a fight where someone knocked their beaks sideways. Their bills—this may not surprise you at this point—cross. This has nothing to do with avian pugilism. It’s a result of evolution. Each crossbill’s beak has evolved to match the particular shape of local pine cones. This didn’t happen overnight. Scientist think this particular bird has been around for about 6,000 years feasting off pine cones in the South Hills, and only in the South Hills of Idaho.

For more on this, check the link. If you want to see a South Hills Crossbill, take a little trip to Castle Rocks State Park. The manager there can point you in the right direction.

http://www.audubon.org/news/how-cross...

#cassiacrossbills

Probably not. People love bluebirds. But there is a potential contender that may meet that only in Idaho test. American Ornithological Society publishes and annual checklist for birders. There are often a few changes on that list, and this year one of those changes is about the South Hills or Cassia Crossbill.

Crossbills are birds that look like they’ve been in a fight where someone knocked their beaks sideways. Their bills—this may not surprise you at this point—cross. This has nothing to do with avian pugilism. It’s a result of evolution. Each crossbill’s beak has evolved to match the particular shape of local pine cones. This didn’t happen overnight. Scientist think this particular bird has been around for about 6,000 years feasting off pine cones in the South Hills, and only in the South Hills of Idaho.

For more on this, check the link. If you want to see a South Hills Crossbill, take a little trip to Castle Rocks State Park. The manager there can point you in the right direction.

http://www.audubon.org/news/how-cross...

#cassiacrossbills

Published on March 08, 2019 04:00

March 7, 2019

An Idaho Crime Fighter

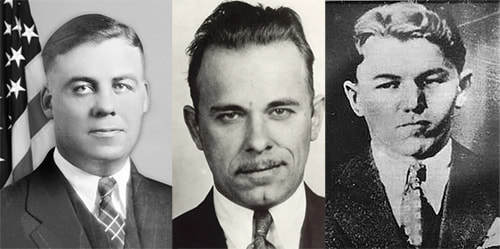

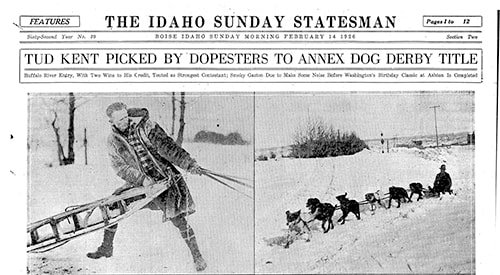

All these years after their deaths, the names John Dillinger and “Baby Face” Nelson are familiar because of their infamy as crime figures. But an Idaho man you’ve probably never heard of was at least partly responsible for the demise of each.

Samuel P. Cowley was born in Franklin, Idaho in July 1899. He went to the Oneida Stake Academy, the Utah Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, and George Washington University in Washington, DC. He graduated from the latter with a law degree.

Cowley entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1929 as an agent and was promoted to inspector in 1934.

It was in July 1934 that a headline reading “Former Preston Man Helps Get Dillinger” ran on the front page of the Preston Citizen. Early reports said that it was Cowley’s bullet that ended the gangster’s life, but that wasn’t certain. Dillinger was gunned down after attending a picture show at the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The film he had been watching was Manhattan Melodrama starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and William Powell.

Things went mostly right when Cowley participated in taking Dillinger down. Not so with “Baby Face” Nelson, whose real name was Lester Gillis.

Just months after the gunfight in Chicago, on November 27, 1934, Cowley and Special Agent Herman E. Hollis stopped Nelson’s car with gunfire. Nelson, and companion John Paul Chase came out of the crippled car shooting. Cowley and Hollis returned fire, hitting and severely wounding Nelson, who would die that evening. Unfortunately, both Cowley and Hollis were also shot. Hollis died that day. Cowley passed away the next morning. John Paul Chase was later captured, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

Samuel P. Cowley was born in Franklin, Idaho in July 1899. He went to the Oneida Stake Academy, the Utah Agricultural College in Logan, Utah, and George Washington University in Washington, DC. He graduated from the latter with a law degree.

Cowley entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1929 as an agent and was promoted to inspector in 1934.

It was in July 1934 that a headline reading “Former Preston Man Helps Get Dillinger” ran on the front page of the Preston Citizen. Early reports said that it was Cowley’s bullet that ended the gangster’s life, but that wasn’t certain. Dillinger was gunned down after attending a picture show at the Biograph Theater in Chicago. The film he had been watching was Manhattan Melodrama starring Clark Gable, Myrna Loy, and William Powell.

Things went mostly right when Cowley participated in taking Dillinger down. Not so with “Baby Face” Nelson, whose real name was Lester Gillis.

Just months after the gunfight in Chicago, on November 27, 1934, Cowley and Special Agent Herman E. Hollis stopped Nelson’s car with gunfire. Nelson, and companion John Paul Chase came out of the crippled car shooting. Cowley and Hollis returned fire, hitting and severely wounding Nelson, who would die that evening. Unfortunately, both Cowley and Hollis were also shot. Hollis died that day. Cowley passed away the next morning. John Paul Chase was later captured, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

FBI photos, left to right, of Agent/Inspector Samuel P. Cowley, John Dillinger, and “Baby Face” Nelson.

Published on March 07, 2019 04:00

March 6, 2019

Boise's Castle Rock

Boise’s Castle Rock formation, according to historian Tod Shallat in the book

Ethnic Landmarks

, was called Eagle Rock by Shoshone and Bannock natives. The balanced rocks reminded them of perched raptors. That was when they were being poetic about the site that may once have been a resting place for their ancestors. They sometimes referred to it as Boa-Sea, a word meaning “bloat” in the Shoshone language, in commemoration of spoiled apples given as government rations to the tribe at one time.

Castle Rock was threatened by development in the 1990s. That led to a lawsuit where the East End Neighborhood Association, the Fort Hall Shoshone Bannocks, and the Duck Valley Paiutes joined forces to protect the rock formation, which was said to be a sacred Indian burial site. The developer produced archeologists who doubted the veracity of native claims.

Historian Merle Wells produced an Idaho Statesman story from 1893 about the discovery of bones during an excavation near the Idaho State Penitentiary. The article said that “The grewsome (sic) find was no surprise to the old timers of the city, who have known for years that many Indians were, during the early days, buried in the rocks on the hills back of where the penitentiary now stands.”

The lawsuit drug on for six years. To help settle the dispute the City of Boise agreed to purchase the site for $500,000. The East End Neighborhood Association added $75,000 of their own to help with the purchase and pay for landscaping in the area.

As a result, the Castle Rock looks much the same today as it did when those bad apples were distributed.

Trails in the area have been relocated to avoid the most sensitive parts of Castle Rock, which is still regarded as a sacred place by the descendants of the people who were the first residents of the area.

#castlerock

Castle Rock was threatened by development in the 1990s. That led to a lawsuit where the East End Neighborhood Association, the Fort Hall Shoshone Bannocks, and the Duck Valley Paiutes joined forces to protect the rock formation, which was said to be a sacred Indian burial site. The developer produced archeologists who doubted the veracity of native claims.

Historian Merle Wells produced an Idaho Statesman story from 1893 about the discovery of bones during an excavation near the Idaho State Penitentiary. The article said that “The grewsome (sic) find was no surprise to the old timers of the city, who have known for years that many Indians were, during the early days, buried in the rocks on the hills back of where the penitentiary now stands.”

The lawsuit drug on for six years. To help settle the dispute the City of Boise agreed to purchase the site for $500,000. The East End Neighborhood Association added $75,000 of their own to help with the purchase and pay for landscaping in the area.

As a result, the Castle Rock looks much the same today as it did when those bad apples were distributed.

Trails in the area have been relocated to avoid the most sensitive parts of Castle Rock, which is still regarded as a sacred place by the descendants of the people who were the first residents of the area.

#castlerock

Published on March 06, 2019 04:00

March 5, 2019

Aviator Cave

Spelunkers keep the location of most caves they know about secret. That’s to keep people who don’t have the proper training from hurting themselves and sometimes to protect cave environments.

There’s one cave in Idaho that gets a lot of extra protection. It’s called Aviator’s Cave and it is within the boundaries of the Idaho National Laboratory, which is in the desert between Idaho Falls and Arco. Since 1949 “the Site,” as it’s known locally, has been a national center for nuclear research. Because of the sensitive nature of that research, security at INL is high. In 1985, that included regular helicopter flyovers to make sure people weren’t intentionally or accidentally trespassing on the federal property.

In January 1985 pilot Mike Atwood was flying about 500 feet above the desert on a routine patrol when he spotted what looked like smoke. Circling around to investigate, he saw that it wasn’t smoke, but steam coming from a visible rift in the lava rock below. Atwood assumed it was condensation from warm air inside a lava tube hitting the sub-zero air in the desert above. He noted the GPS coordinates of the site and paid no more attention to it.

Lava tubes are common there in the Idaho desert, not far from Craters of the Moon National Monument. The caves were formed some 30,000 years ago when rivers of lava spewed from the earth, flowing downhill like water. The lava rivers would cool from the outside first forming a tube or roof over the molten lava still flowing beneath. Like a garden hose when the water is shut off the molten lava would drain out leaving a cave sometimes miles long.

Three years after his winter encounter with the steam and in a warmer season, Atwood’s curiosity surfaced. He decided to go back and investigate the hole he had found. When he flew to the coordinates he’d noted, Atwood saw that the vegetation around the dark shadow on the ground was a brighter shade of green than the surrounding rabbit brush.

About 30 feet from the hole he found a spot clear enough to land. As he walked closer to the cave he began to see buffalo skulls and other bones inside. He climbed down to the opening, stooped to get inside, and found that the cave opened up once past the lip. Standing up was easy.

It was immediately obvious that Atwood was not the first person to stand in that cave, though he was the first to stand there in a very long time. Among the scattered bones were obsidian chips and projectile points, evidence that native hunters had at least stopped in the cave if they had not lived there. Atwood, and later others, found more fragile evidence of human occupation, including objects made from plant material and fur.

Today this important archeological site remains doubly protected by its status as a place of scientific study and a place within a modern well-protected place of scientific study. Aviator’s Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

The INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

#INL #aviatorcave

There’s one cave in Idaho that gets a lot of extra protection. It’s called Aviator’s Cave and it is within the boundaries of the Idaho National Laboratory, which is in the desert between Idaho Falls and Arco. Since 1949 “the Site,” as it’s known locally, has been a national center for nuclear research. Because of the sensitive nature of that research, security at INL is high. In 1985, that included regular helicopter flyovers to make sure people weren’t intentionally or accidentally trespassing on the federal property.

In January 1985 pilot Mike Atwood was flying about 500 feet above the desert on a routine patrol when he spotted what looked like smoke. Circling around to investigate, he saw that it wasn’t smoke, but steam coming from a visible rift in the lava rock below. Atwood assumed it was condensation from warm air inside a lava tube hitting the sub-zero air in the desert above. He noted the GPS coordinates of the site and paid no more attention to it.

Lava tubes are common there in the Idaho desert, not far from Craters of the Moon National Monument. The caves were formed some 30,000 years ago when rivers of lava spewed from the earth, flowing downhill like water. The lava rivers would cool from the outside first forming a tube or roof over the molten lava still flowing beneath. Like a garden hose when the water is shut off the molten lava would drain out leaving a cave sometimes miles long.

Three years after his winter encounter with the steam and in a warmer season, Atwood’s curiosity surfaced. He decided to go back and investigate the hole he had found. When he flew to the coordinates he’d noted, Atwood saw that the vegetation around the dark shadow on the ground was a brighter shade of green than the surrounding rabbit brush.

About 30 feet from the hole he found a spot clear enough to land. As he walked closer to the cave he began to see buffalo skulls and other bones inside. He climbed down to the opening, stooped to get inside, and found that the cave opened up once past the lip. Standing up was easy.

It was immediately obvious that Atwood was not the first person to stand in that cave, though he was the first to stand there in a very long time. Among the scattered bones were obsidian chips and projectile points, evidence that native hunters had at least stopped in the cave if they had not lived there. Atwood, and later others, found more fragile evidence of human occupation, including objects made from plant material and fur.

Today this important archeological site remains doubly protected by its status as a place of scientific study and a place within a modern well-protected place of scientific study. Aviator’s Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

The INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

#INL #aviatorcave

Published on March 05, 2019 04:00

March 4, 2019

Still Sledding After all these Years

Dog sleds were about the only speedy means of transportation around the turn of the century when snow blanketed the Island Park area in the winter. Humans, being human, turned transportation into a contest. Dogs, being dogs, went along with it, probably with a lot of eager huffing and some brag-barking of their own.

One of the oldest dog sled races in the country takes place each February in Ashton. The American Dog Derby is billed as “The oldest all-American dog sled race.” It celebrated its centennial in January 2017. You already know, if you’ve done your math, that the first race took place in 1917. Wikipedia throws a little water on the “oldest” claim by pointing out that there was a dog sled race in Truckee, California during the winter of 1914-15. The Ashton race seems to have the longest history in any case, though there were a few years it wasn’t run.

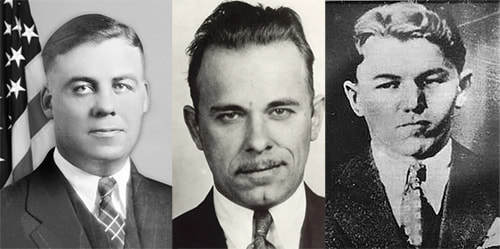

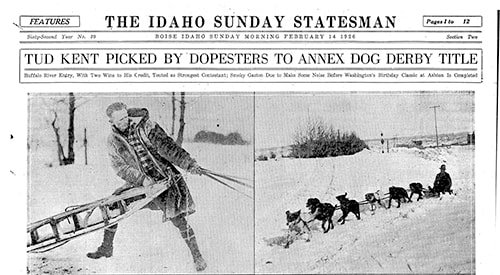

The race merited full-page coverage on February 14, 1926, in a story that was capped off with this observation: “Ashton is on the way to the dogs again, as it goes annually, when for a day the little town on the fringe of the Targhee forest is the sport capital of the nation while its famous dog derby is run.”

Tud Kent, who won the first American Dog Derby in 1917, was favored to win the 1926 race, according to the Statesman (below).

One of the oldest dog sled races in the country takes place each February in Ashton. The American Dog Derby is billed as “The oldest all-American dog sled race.” It celebrated its centennial in January 2017. You already know, if you’ve done your math, that the first race took place in 1917. Wikipedia throws a little water on the “oldest” claim by pointing out that there was a dog sled race in Truckee, California during the winter of 1914-15. The Ashton race seems to have the longest history in any case, though there were a few years it wasn’t run.

The race merited full-page coverage on February 14, 1926, in a story that was capped off with this observation: “Ashton is on the way to the dogs again, as it goes annually, when for a day the little town on the fringe of the Targhee forest is the sport capital of the nation while its famous dog derby is run.”

Tud Kent, who won the first American Dog Derby in 1917, was favored to win the 1926 race, according to the Statesman (below).

Published on March 04, 2019 05:19

March 3, 2019

Why the Signs Went Away

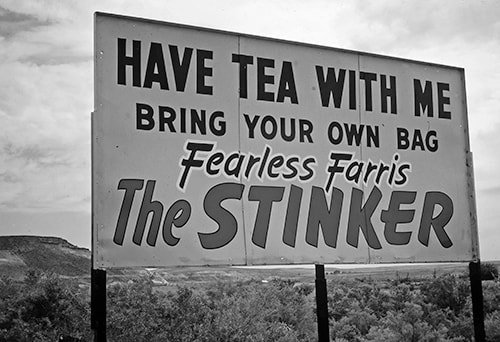

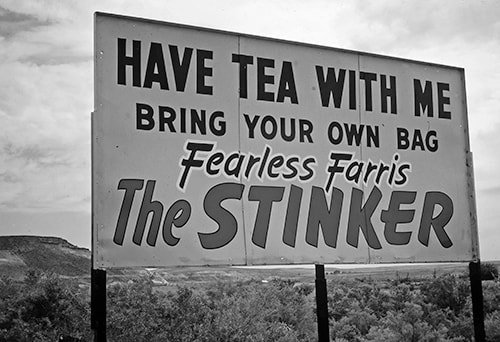

I’m finishing up my latest book, Fearless—Farris Lind, the Man Behind the Skunk. It will be available in a few weeks. Meanwhile, I’ve been posting some of the stories from the book.

Have you ever asked yourself whatever happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

Farris Lind had built his business on humor. Suddenly, in 1965 someone wanted to throw a bucket of cold water all over the most visible part of his funny business. That someone was Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as First Lady “Ladybird” Johnson.

The Highway Beautification Act (HBA) of 1965 was Ladybird Johnson’s signature issue. She and her supporters were getting tired of the proliferation of billboards alongside federal highways in the United States. The act prohibited most outdoor advertising along Interstate and federal highways and required removal or screening of junkyards in highway viewsheds.

The law threatened a key component of Farris Lind's success. In 1969, he sued the State of Idaho because the Legislature had passed laws to bring the state into compliance with the HBA. Signs were not allowed within 660 feet of a federal highway right-of-way. Lind said, "The federal and state government have no right to deprive a farmer or other landowner of any rental income he can get from signs on his property. I owe it to myself to take a swing at bureaucracy" (Capital Journal, December 12, 1969).

For signs on private property, Lind was paying $10-$15 a month rental. Some signs were on property he'd purchased.

The lawsuit asked that the highway beautification law be declared unconstitutional. Lind contended that it was unconstitutional because it prohibited the right to conduct a lawful business and impaired contractual arrangements Lind had with landowners.

The suit didn't gain any traction, and most of the signs came down, ending a run of about 25 years of memorable advertising.

#stinkerstations #stinkerstores #fearlessfarris

Have you ever asked yourself whatever happened to all those Stinker Station signs?

Farris Lind had built his business on humor. Suddenly, in 1965 someone wanted to throw a bucket of cold water all over the most visible part of his funny business. That someone was Claudia Alta Johnson, better known as First Lady “Ladybird” Johnson.

The Highway Beautification Act (HBA) of 1965 was Ladybird Johnson’s signature issue. She and her supporters were getting tired of the proliferation of billboards alongside federal highways in the United States. The act prohibited most outdoor advertising along Interstate and federal highways and required removal or screening of junkyards in highway viewsheds.

The law threatened a key component of Farris Lind's success. In 1969, he sued the State of Idaho because the Legislature had passed laws to bring the state into compliance with the HBA. Signs were not allowed within 660 feet of a federal highway right-of-way. Lind said, "The federal and state government have no right to deprive a farmer or other landowner of any rental income he can get from signs on his property. I owe it to myself to take a swing at bureaucracy" (Capital Journal, December 12, 1969).

For signs on private property, Lind was paying $10-$15 a month rental. Some signs were on property he'd purchased.

The lawsuit asked that the highway beautification law be declared unconstitutional. Lind contended that it was unconstitutional because it prohibited the right to conduct a lawful business and impaired contractual arrangements Lind had with landowners.

The suit didn't gain any traction, and most of the signs came down, ending a run of about 25 years of memorable advertising.

#stinkerstations #stinkerstores #fearlessfarris

Published on March 03, 2019 04:00

March 2, 2019

A Somewhat Reluctant Idahoan

Most Idahoans would rather live here than anywhere else. Today’s story is about a woman who desperately wanted to stay away, yet went on to popularize Idaho in illustration and story.

Mary Hallock grew up in New York, and received her education in Boston. She socialized with the elite of New England, but she fell in love with a civil engineer named Arthur Foote who had the grit of the West beneath his fingernails.

Mary Hallock Foote came West in the nation's Centennial year, 1876, but she did not come eagerly. Mrs. Foote once wrote, "No girl ever wanted less to go West with any man, or paid a man a greater compliment by doing so."

The Foote's lived in Idaho from 1883 to 1895, mostly in the Boise River Canyon near present day Lucky Peak Dam. It was a frustrating, heartbreaking time for them, but Mary made use of her hard experience. She was an illustrator for books and magazines of the era. In fact, she was once called the dean of women illustrators.

Encouraged by an editor to write as well, she became a popular author.

Mary Hallock Foote wrote many short stories, and a dozen novels. Much of her writing was based on her years in Idaho. Coeur d'Alene, Silver City, Boise, Thousand Springs, and Craters of the Moon were all settings for her stories.

In 1971 she was the subject of an enchanting—if controversial—story herself. Wallace Stegner's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose is based on the fascinating life of Mary Hallock Foote... a somewhat reluctant Idahoan.

I’m pleased to say that a new Foote Park interpretive exhibit opened last fall. You can reach it by crossing Lucky Peak Dam and taking the first road to your right. There is a restroom on site and plenty of parking. It’s well worth a few minutes of your time.

#footepark #maryhallockfoote #idahohistory This illustration by Mary Hallock Foote depicts the veranda in front of their home in the Boise River Canyon.

This illustration by Mary Hallock Foote depicts the veranda in front of their home in the Boise River Canyon.

Mary Hallock grew up in New York, and received her education in Boston. She socialized with the elite of New England, but she fell in love with a civil engineer named Arthur Foote who had the grit of the West beneath his fingernails.

Mary Hallock Foote came West in the nation's Centennial year, 1876, but she did not come eagerly. Mrs. Foote once wrote, "No girl ever wanted less to go West with any man, or paid a man a greater compliment by doing so."

The Foote's lived in Idaho from 1883 to 1895, mostly in the Boise River Canyon near present day Lucky Peak Dam. It was a frustrating, heartbreaking time for them, but Mary made use of her hard experience. She was an illustrator for books and magazines of the era. In fact, she was once called the dean of women illustrators.

Encouraged by an editor to write as well, she became a popular author.

Mary Hallock Foote wrote many short stories, and a dozen novels. Much of her writing was based on her years in Idaho. Coeur d'Alene, Silver City, Boise, Thousand Springs, and Craters of the Moon were all settings for her stories.

In 1971 she was the subject of an enchanting—if controversial—story herself. Wallace Stegner's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose is based on the fascinating life of Mary Hallock Foote... a somewhat reluctant Idahoan.

I’m pleased to say that a new Foote Park interpretive exhibit opened last fall. You can reach it by crossing Lucky Peak Dam and taking the first road to your right. There is a restroom on site and plenty of parking. It’s well worth a few minutes of your time.

#footepark #maryhallockfoote #idahohistory

This illustration by Mary Hallock Foote depicts the veranda in front of their home in the Boise River Canyon.

This illustration by Mary Hallock Foote depicts the veranda in front of their home in the Boise River Canyon.

Published on March 02, 2019 04:00

March 1, 2019

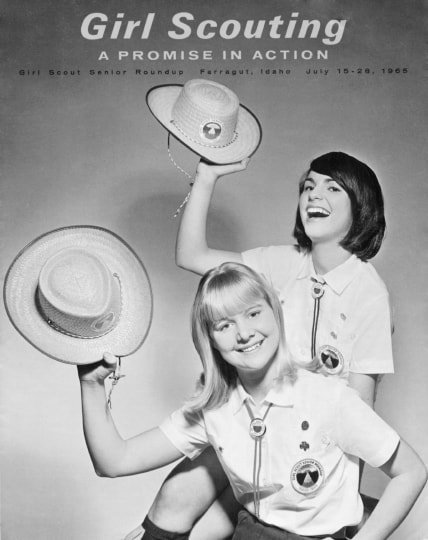

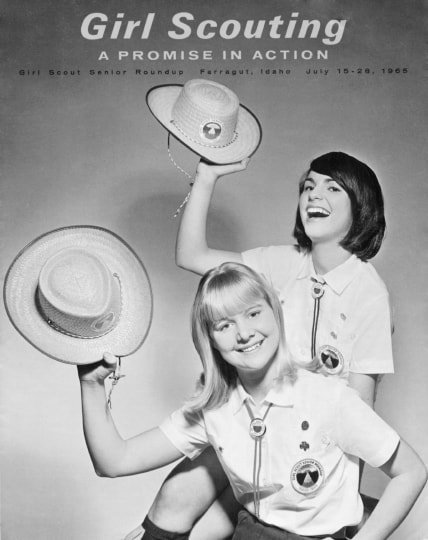

The Girl Scouts and State Parks

The Girl Scouts played a huge role in the creation of Idaho’s state parks system. Governor Robert E. Smylie had been trying to convince the Legislature for years to create a system of state parks managed by professionals. In 1965 a lot of things came together to make Smylie’s idea palatable to Legislators. He’d lined up the gift of the Railroad Ranch, which would later become Harriman State Park. The Federal Land and Water Conservation Fund program was created, offering funding for park development. The state had recently traded land that was about to end up under Dworshak Reservoir for that old Navy base on the shores of Lake Pend Orielle.

The Girl Scouts sealed the deal, though. Smylie convinced them that Farragut would be the perfect place to hold the 1965 national Girl Scout Senior Roundup. It would bring a lot of money into north Idaho. So, with that commitment from the girl scouts in hand, the Legislature finally gave Smylie the parks department he was looking for.

Now, if you’re thinking it was the Boy Scouts that had the big gatherings, you’re not wrong. Just two days after the Girl Scout Roundup concluded, Governor Smylie sent out a press release announcing that Farragut had been selected as the site for the World Boy Scout Jamboree. Smylie, said, “Idaho is bigger today. The biggest planned event in Idaho’s history is no longer a hope; it’s an assured occurrence.”

That was a great event, and so were national Boy Scout events that came along in following years. But it was the Girl Scouts who led the way.

During the opening ceremonies for the 1965 Senior Girl Scout Roundup (photo at bottom) Governor Smylie shouted over the noise, “If you want a comparison in numbers, there are as many people here on this Idaho spot right now as live in Caldwell.” The program opened with 11,000 voices singing Girl Scout songs, recordings of which still sell occasionally on eBay today.

The Girl Scouts sealed the deal, though. Smylie convinced them that Farragut would be the perfect place to hold the 1965 national Girl Scout Senior Roundup. It would bring a lot of money into north Idaho. So, with that commitment from the girl scouts in hand, the Legislature finally gave Smylie the parks department he was looking for.

Now, if you’re thinking it was the Boy Scouts that had the big gatherings, you’re not wrong. Just two days after the Girl Scout Roundup concluded, Governor Smylie sent out a press release announcing that Farragut had been selected as the site for the World Boy Scout Jamboree. Smylie, said, “Idaho is bigger today. The biggest planned event in Idaho’s history is no longer a hope; it’s an assured occurrence.”

That was a great event, and so were national Boy Scout events that came along in following years. But it was the Girl Scouts who led the way.

During the opening ceremonies for the 1965 Senior Girl Scout Roundup (photo at bottom) Governor Smylie shouted over the noise, “If you want a comparison in numbers, there are as many people here on this Idaho spot right now as live in Caldwell.” The program opened with 11,000 voices singing Girl Scout songs, recordings of which still sell occasionally on eBay today.

Published on March 01, 2019 05:09