Rick Just's Blog, page 208

February 8, 2019

The First Wheels in Idaho

In 2016, the US Census Bureau estimated the population of Idaho as 1,683,140. Meanwhile, the Idaho Transportation Department registered 1.7 million vehicles that same year. So, every man, woman, and child in the state could, theoretically, have their own set of wheels. Yet, it wasn’t that long ago there wasn’t a single wheel in sight.

The first wheel to enter what is now Idaho, was probably one of four on what was the first wagon to come here. That was in 1836, when the Reverend and Mrs. Henry Spalding, accompanied by Dr. and Mrs. Marcus Whitman arrived in this land. They had run out of road when they hit the Green River in Wyoming, then struck out across country on their mission to spread their religion.

The missionaries got the wagon nearly to where Fort Hall had been established as a trading post two years earlier. The going got tougher, so they abandoned two of the wheels and converted their wagon into a cart. That got them at least to Fort Boise (the early version of same, which was also a fur trading establishment).

We’re only concerned with that first wheel today, so won’t tell more about the Spaldings and the Lapwai Mission printing press, or the demise of the Whitmans, which discouraged the Spaldings out of almost-Idaho in 1847. Not this time.

#spalding #whitmans

The first wheel to enter what is now Idaho, was probably one of four on what was the first wagon to come here. That was in 1836, when the Reverend and Mrs. Henry Spalding, accompanied by Dr. and Mrs. Marcus Whitman arrived in this land. They had run out of road when they hit the Green River in Wyoming, then struck out across country on their mission to spread their religion.

The missionaries got the wagon nearly to where Fort Hall had been established as a trading post two years earlier. The going got tougher, so they abandoned two of the wheels and converted their wagon into a cart. That got them at least to Fort Boise (the early version of same, which was also a fur trading establishment).

We’re only concerned with that first wheel today, so won’t tell more about the Spaldings and the Lapwai Mission printing press, or the demise of the Whitmans, which discouraged the Spaldings out of almost-Idaho in 1847. Not this time.

#spalding #whitmans

Published on February 08, 2019 04:00

February 7, 2019

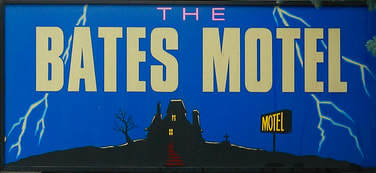

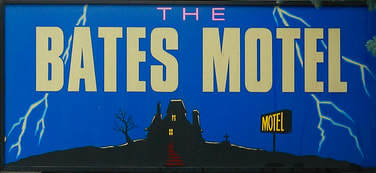

The Bates Motel

If you’ve seen the 1960 Alfred Hitchcock movie, Psycho starring Janet Leigh, you probably think of it every time you step into a motel shower. That stabbing music—and that stabbing—tend to stick in the brain.

An entrepreneur in Coeur d’Alene either decided to take advantage of the movie’s fame by naming his lodging site the Bates Motel, after the one in the movie, or he happened to be named Bates (possibly Randy Bates), and simply took advantage of the coincidence. Alert readers in Coeur d’Alene will have opinions.

In any case any connection to the movie or the more recent TV series named Bates Motel is tangential at best. There is a rumor, retold endlessly in blurbs such as this one, that Robert Bloch, the man who wrote the book Psycho once stayed at the motel. Good luck chasing that down. Another rumor says that the very Psycho-like sign (photo) that encouraged people to spend the night there for many years was made by a movie production company that used the motel for a movie, or maybe just stayed there.

Gosh, what if they stayed in room 1 or room 3? Did the ashtrays move inexplicably? Did they feel a chill in the air?

Yes, the other thing the Bates Motel was famous for was that it was allegedly haunted, those rooms holding most of the hauntings. There doesn’t seem to be a death associated with the hauntings, so just random ghosts, I guess.

The old motel was originally officer’s quarters at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Maybe. Many old buildings in the area started out there, so that’s not far-fetched.

About the only thing we can say for sure about the Bates Motel once at 2018 E. Sherman Ave., is that it is no longer called that. It’s the Lighthouse, now. No word on whether or not the ghosts moved out in disgust when the name changed.

#batesmotel #coeurd’alene #psycho

An entrepreneur in Coeur d’Alene either decided to take advantage of the movie’s fame by naming his lodging site the Bates Motel, after the one in the movie, or he happened to be named Bates (possibly Randy Bates), and simply took advantage of the coincidence. Alert readers in Coeur d’Alene will have opinions.

In any case any connection to the movie or the more recent TV series named Bates Motel is tangential at best. There is a rumor, retold endlessly in blurbs such as this one, that Robert Bloch, the man who wrote the book Psycho once stayed at the motel. Good luck chasing that down. Another rumor says that the very Psycho-like sign (photo) that encouraged people to spend the night there for many years was made by a movie production company that used the motel for a movie, or maybe just stayed there.

Gosh, what if they stayed in room 1 or room 3? Did the ashtrays move inexplicably? Did they feel a chill in the air?

Yes, the other thing the Bates Motel was famous for was that it was allegedly haunted, those rooms holding most of the hauntings. There doesn’t seem to be a death associated with the hauntings, so just random ghosts, I guess.

The old motel was originally officer’s quarters at the Farragut Naval Training Station. Maybe. Many old buildings in the area started out there, so that’s not far-fetched.

About the only thing we can say for sure about the Bates Motel once at 2018 E. Sherman Ave., is that it is no longer called that. It’s the Lighthouse, now. No word on whether or not the ghosts moved out in disgust when the name changed.

#batesmotel #coeurd’alene #psycho

Published on February 07, 2019 08:30

February 6, 2019

An Idaho First

I often find myself thinking, “everybody knows that” when I’m working on these short historical vignettes. As it turns out, I am regularly able to find a little bit of Idaho trivia that is brand new to a lot of people. Also, it’s not uncommon that my posts generate some feedback that includes something I didn’t know about the story. I really appreciate that.

Part of the reason I do this every day is that I frequently learn something new, myself. Today’s post is a good example.

I knew that Arrowrock Dam, dedicated in 1915, was the tallest dam in the world, for a little while. That’s always intrigued me, because by the standards of, say, Hoover, or Dworshak, it isn’t all that impressive. At 366 feet it held that title until 1924, when a dam in Switzerland knocked it from the throne.

But in reviewing the history of Arrowrock dam recently, I found a little Idaho first that was completely new to me. I informally collect tidbits where Idaho or an Idahoan was the first at something to defy the cynics who seem to think we’re always the last ones to the party.

This obscure first regards the railroad line that was built from the community of Barber all the way along the Boise River to the construction site of the Arrowrock Dam. The Barber Lumber Company was interested in a rail line along that stretch that could haul timber out of the mountains. In fact, they owned the right of way where the line would need to go. So, the Bureau of Reclamation worked out an agreement with Barber Lumber company where Reclamation would lease the tracks and run the railroad. That made the Arrowrock and Barber Railroad the first publicly owned line in the nation.

The Arrowrock and Barber Railroad ran from—wait for it—Arrowrock to Barber and back. The Oregon Shortline ran from Barber to the new Reclamation office in Boise, where materials were warehoused and sent to the construction site as needed. The Reclamation Service Boise Project Office, at 214 Broadway Avenue in Boise, was listed on the National Register of Historic Place in 2010.

#arrowrock #tallestdam

Part of the reason I do this every day is that I frequently learn something new, myself. Today’s post is a good example.

I knew that Arrowrock Dam, dedicated in 1915, was the tallest dam in the world, for a little while. That’s always intrigued me, because by the standards of, say, Hoover, or Dworshak, it isn’t all that impressive. At 366 feet it held that title until 1924, when a dam in Switzerland knocked it from the throne.

But in reviewing the history of Arrowrock dam recently, I found a little Idaho first that was completely new to me. I informally collect tidbits where Idaho or an Idahoan was the first at something to defy the cynics who seem to think we’re always the last ones to the party.

This obscure first regards the railroad line that was built from the community of Barber all the way along the Boise River to the construction site of the Arrowrock Dam. The Barber Lumber Company was interested in a rail line along that stretch that could haul timber out of the mountains. In fact, they owned the right of way where the line would need to go. So, the Bureau of Reclamation worked out an agreement with Barber Lumber company where Reclamation would lease the tracks and run the railroad. That made the Arrowrock and Barber Railroad the first publicly owned line in the nation.

The Arrowrock and Barber Railroad ran from—wait for it—Arrowrock to Barber and back. The Oregon Shortline ran from Barber to the new Reclamation office in Boise, where materials were warehoused and sent to the construction site as needed. The Reclamation Service Boise Project Office, at 214 Broadway Avenue in Boise, was listed on the National Register of Historic Place in 2010.

#arrowrock #tallestdam

Published on February 06, 2019 04:00

February 5, 2019

How much coal?

Seeing this 1939 photo of a steam locomotive pulling into Glenns Ferry caused me to wonder about how much coal was used by your average train. As it turns out, it’s a bit like asking how much wood could a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood.

The answer is, it depends. It depends on the size of the engine, the grade of the coal, the steepness of the terrain, and how much tonnage the locomotive is pulling. Temperature was also a factor. If it was winter, passenger trains were heated by steam generated by the locomotive, which made them less efficient at pulling.

I found some comments on the trusty internet from a former locomotive engineer for Union Pacific who said coal powered trains typically made stops every hundred miles or so to load up with more coal. Of course, that depends, too. It depends on the size of the tender and all the other “depends” listed above. The same engineer noted that trains had to stop twice as often to take on water, which was just as important as coal.

And, what about the guy shoveling the coal? Did he ever get a break? Not really. You didn’t want to put too much coal on at once or it wouldn’t burn efficiently. Experienced firemen would lift six to nine shovels full and dump them into the burner.

Now that I’ve given you almost no information you can really count on, I’m going to trust that some of the train fanatics who read these posts will set me straight. I’m looking at you, John Wood!

#steamengine #locomotive #glennsferry

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

The answer is, it depends. It depends on the size of the engine, the grade of the coal, the steepness of the terrain, and how much tonnage the locomotive is pulling. Temperature was also a factor. If it was winter, passenger trains were heated by steam generated by the locomotive, which made them less efficient at pulling.

I found some comments on the trusty internet from a former locomotive engineer for Union Pacific who said coal powered trains typically made stops every hundred miles or so to load up with more coal. Of course, that depends, too. It depends on the size of the tender and all the other “depends” listed above. The same engineer noted that trains had to stop twice as often to take on water, which was just as important as coal.

And, what about the guy shoveling the coal? Did he ever get a break? Not really. You didn’t want to put too much coal on at once or it wouldn’t burn efficiently. Experienced firemen would lift six to nine shovels full and dump them into the burner.

Now that I’ve given you almost no information you can really count on, I’m going to trust that some of the train fanatics who read these posts will set me straight. I’m looking at you, John Wood!

#steamengine #locomotive #glennsferry

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on February 05, 2019 04:00

February 4, 2019

My latest column from Idaho Press

Published on February 04, 2019 05:08

February 3, 2019

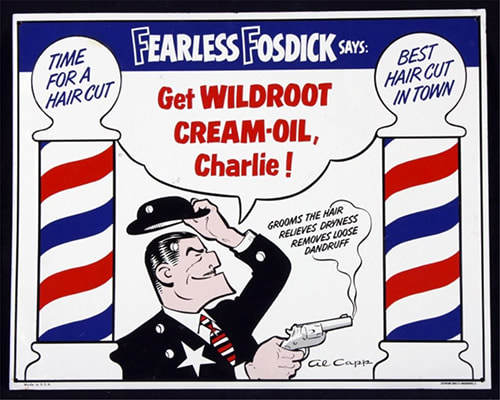

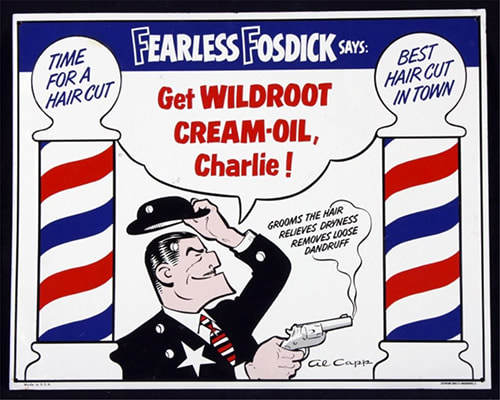

Fearless... Fosdick

I’m working on a book about “Fearless” Farris Lind, his Stinker Stations, and the quirky signs that were their signature advertising scheme during the 40s, 50s, and into the 60s.

Given that Farris Lind was a Navy fighter pilot instructor during World War II, and later a crop duster, one might assume that’s where he got the nickname Fearless Farris. Not so. Lind got the idea for the name from Fearless Fosdick, the cartoon character Al Capp drew as a parody of Dick Tracy. Lind knew the alliteration would make it easy to remember. He invented the story that he was Fearless Farris because the “big guy” oil companies didn’t scare him. The first neon sign for his Boise service station featured a boxer under the words “Fearless Farris.”

The iconic skunk, also a boxer, would come along later when a competitor called Lind a “stinker” for his cut rate prices for gasoline. Was Lind insulted? Oh, gosh, no. He latched onto that name like a leg trap. In no time his growing chain of outlets became Stinker Stations with a skunk logo.

There’s much more to tell, of course, stories of tragedy, comedy, and courage. The book will be out this spring.

#stinkerstations #fearlessfarris #fearlesfosdick

Given that Farris Lind was a Navy fighter pilot instructor during World War II, and later a crop duster, one might assume that’s where he got the nickname Fearless Farris. Not so. Lind got the idea for the name from Fearless Fosdick, the cartoon character Al Capp drew as a parody of Dick Tracy. Lind knew the alliteration would make it easy to remember. He invented the story that he was Fearless Farris because the “big guy” oil companies didn’t scare him. The first neon sign for his Boise service station featured a boxer under the words “Fearless Farris.”

The iconic skunk, also a boxer, would come along later when a competitor called Lind a “stinker” for his cut rate prices for gasoline. Was Lind insulted? Oh, gosh, no. He latched onto that name like a leg trap. In no time his growing chain of outlets became Stinker Stations with a skunk logo.

There’s much more to tell, of course, stories of tragedy, comedy, and courage. The book will be out this spring.

#stinkerstations #fearlessfarris #fearlesfosdick

Published on February 03, 2019 04:00

February 2, 2019

Do You Have Enough Legroom?

There is a lot of history buried in cemeteries, some of it a little quirky. The Oneida County Relic Preservation and Historical Society in Malad City has a story on their website, written by Sue Thomas that lives up to that label.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

Published on February 02, 2019 04:00

February 1, 2019

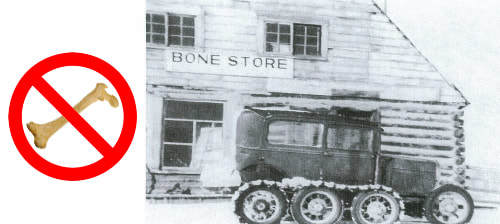

Not that kind of Bone

Bone is an evocative name. It brings forth images of dusty desert with bleached carcasses of oxen left behind by struggling pioneers.

You may be disappointed to know, though, that Bone, Idaho does not have its roots in immigrant travails or some long-forgotten massacre. It was named after Orin or Orion G. Bone, an early settler. He got there in about 1910.

Mr. Bone thought the place needed a general store, so he moved a schoolhouse building from Birch Creek and started a business called the Bone Store.

If you’ve heard of Bone at all it’s probably because of that store. The store and post office (1917-1950) eventually acquired a grille and a bar. Patrons tacked hundreds of dollar bills with their names on them on the ceiling for some reason lost in time. Local branding irons were used to burn atmosphere into the wooden walls. It operated until a few years ago when it apparently became a losing proposition.

What drew folks to Bone in the first place? The prospect of operating dry land farms, mostly wheat. They still raise wheat in the area and it is a popular snowmobile destination. If you go to Bone you’ll probably go up through Ammon, just outside of Idaho Falls, but it’s almost directly east of Firth as the crow flies.

It got a brief moment of fame in 1982 when the NBC daytime program Fantasy gave the residents of Bone their “fantasy,” which was a telephone for each of the 23 residents. It’s doubtful this was high on the fantasy list for most people, since telephone service had actually been brought to the community earlier in the year. They were happy to play along with the show, which lasted only a couple of seasons, and accept their free telephones.

Thanks to Julie Braun Williams, who grew up there, for her help on this story.

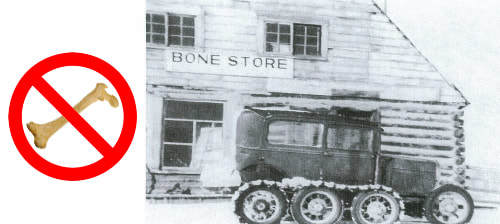

#idahohistory #boneidaho The early version of the Bone Store was a log building. It was located south of the present building, which is no longer in operation. This picture of a snowcat was probably taken in the 1930s.

The early version of the Bone Store was a log building. It was located south of the present building, which is no longer in operation. This picture of a snowcat was probably taken in the 1930s.  This is a picture of the Otteson home near Bone taken in about 1911 or 1912. From Left is, Lenore, Vern, Ray, Alan, Nephi, Dean, and Golden Otteson. The woman on the far right with the horse is unidentified.

This is a picture of the Otteson home near Bone taken in about 1911 or 1912. From Left is, Lenore, Vern, Ray, Alan, Nephi, Dean, and Golden Otteson. The woman on the far right with the horse is unidentified.

You may be disappointed to know, though, that Bone, Idaho does not have its roots in immigrant travails or some long-forgotten massacre. It was named after Orin or Orion G. Bone, an early settler. He got there in about 1910.

Mr. Bone thought the place needed a general store, so he moved a schoolhouse building from Birch Creek and started a business called the Bone Store.

If you’ve heard of Bone at all it’s probably because of that store. The store and post office (1917-1950) eventually acquired a grille and a bar. Patrons tacked hundreds of dollar bills with their names on them on the ceiling for some reason lost in time. Local branding irons were used to burn atmosphere into the wooden walls. It operated until a few years ago when it apparently became a losing proposition.

What drew folks to Bone in the first place? The prospect of operating dry land farms, mostly wheat. They still raise wheat in the area and it is a popular snowmobile destination. If you go to Bone you’ll probably go up through Ammon, just outside of Idaho Falls, but it’s almost directly east of Firth as the crow flies.

It got a brief moment of fame in 1982 when the NBC daytime program Fantasy gave the residents of Bone their “fantasy,” which was a telephone for each of the 23 residents. It’s doubtful this was high on the fantasy list for most people, since telephone service had actually been brought to the community earlier in the year. They were happy to play along with the show, which lasted only a couple of seasons, and accept their free telephones.

Thanks to Julie Braun Williams, who grew up there, for her help on this story.

#idahohistory #boneidaho

The early version of the Bone Store was a log building. It was located south of the present building, which is no longer in operation. This picture of a snowcat was probably taken in the 1930s.

The early version of the Bone Store was a log building. It was located south of the present building, which is no longer in operation. This picture of a snowcat was probably taken in the 1930s.  This is a picture of the Otteson home near Bone taken in about 1911 or 1912. From Left is, Lenore, Vern, Ray, Alan, Nephi, Dean, and Golden Otteson. The woman on the far right with the horse is unidentified.

This is a picture of the Otteson home near Bone taken in about 1911 or 1912. From Left is, Lenore, Vern, Ray, Alan, Nephi, Dean, and Golden Otteson. The woman on the far right with the horse is unidentified.

Published on February 01, 2019 04:00

January 31, 2019

2B or not 2B

2B or not 2B—that is the question: Whether ‘tis nobler to be from Bear Lake County or one of Idaho’s 43 other counties.

Since 1945 Idahoans could tell where most cars are registered simply by looking at their license plates. It’s handy if you want to grouse about the “Great State of Ada,” or that BMW from Sun Valley, or that clueless driver yet to find his or her turn signal switch from, say, Canyon County (just to pick one at random).

The way it works, in case you just moved here from California (to pick a state at random), is that the letter stands for the first letter in the county, and the number refers to where that county would rank in an alphabetical list. For instance, 1B is from Bannock County and 2B is from Bear Lake County.

Learning the county designators, and thus the counties has been a great game for road-weary kids for generations. Then, along came personalized and specialty plates. Neither carries a county designator, so if you want to go incognito you can get a personalized plate such as GOFISH. It’ll cost you a little extra. Also, you could show your affinity for some activity, group, or whatever by getting a specialty plate.

Legislators have mucked around with limits on how many kinds of specialty plates are allowed several times. They seem to have given up on limits nowadays if you can find enough friends who also want a plate that shows their affinity for horned toads or counted cross-stitch. The plates must sell X number a year (also a moving target in any given legislative year) for two years. The last time I checked there were more than 70 specialty plates available. If you want your specialty Corvette plate to read 2RICH, you can do that. Specialty plates can have a personal message.

#idahohistory #licenseplates #idaholicenseplates

Since 1945 Idahoans could tell where most cars are registered simply by looking at their license plates. It’s handy if you want to grouse about the “Great State of Ada,” or that BMW from Sun Valley, or that clueless driver yet to find his or her turn signal switch from, say, Canyon County (just to pick one at random).

The way it works, in case you just moved here from California (to pick a state at random), is that the letter stands for the first letter in the county, and the number refers to where that county would rank in an alphabetical list. For instance, 1B is from Bannock County and 2B is from Bear Lake County.

Learning the county designators, and thus the counties has been a great game for road-weary kids for generations. Then, along came personalized and specialty plates. Neither carries a county designator, so if you want to go incognito you can get a personalized plate such as GOFISH. It’ll cost you a little extra. Also, you could show your affinity for some activity, group, or whatever by getting a specialty plate.

Legislators have mucked around with limits on how many kinds of specialty plates are allowed several times. They seem to have given up on limits nowadays if you can find enough friends who also want a plate that shows their affinity for horned toads or counted cross-stitch. The plates must sell X number a year (also a moving target in any given legislative year) for two years. The last time I checked there were more than 70 specialty plates available. If you want your specialty Corvette plate to read 2RICH, you can do that. Specialty plates can have a personal message.

#idahohistory #licenseplates #idaholicenseplates

Published on January 31, 2019 04:00

January 30, 2019

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). Charlie Ryan wrote what popular car song after an incident on Lewiston Hill?

A. Mustang Sally

B. Thunder Road

C. Hot Rod Lincoln

D. Little Deuce Coupe

E. One Piece at a Time

2). What was Rosalee Sorrels song gave an Idaho governor grief?

A. Nevada Moon

B. I’ve Got a Home Out in Utah

C. Way Out in Idaho

D. My Last Go Round

E. White Clouds

3). What Idaho hotel got a terrible review in 1874?

A. Hotel Sterrit.

B. The Idanha, Boise.

C. The Idanha, Soda Springs.

D. The Northside Inn.

E. Hotel Boise.

4). What got a funeral in Wallace in 1991?

A. A jackass.

B. A mint condition ’34 Ford.

C. A Pulaski.

D. A stoplight.

E. A stop sign.

5) How did “melon gravel” get its name?

A. Named in a scientific paper.

B. Inspired by a Stinker Station sign.

C. Because it looks like petrified watermelons.

D. All of the above.

Answers

1, C

2, E

3, A

4, C

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). Charlie Ryan wrote what popular car song after an incident on Lewiston Hill?

A. Mustang Sally

B. Thunder Road

C. Hot Rod Lincoln

D. Little Deuce Coupe

E. One Piece at a Time

2). What was Rosalee Sorrels song gave an Idaho governor grief?

A. Nevada Moon

B. I’ve Got a Home Out in Utah

C. Way Out in Idaho

D. My Last Go Round

E. White Clouds

3). What Idaho hotel got a terrible review in 1874?

A. Hotel Sterrit.

B. The Idanha, Boise.

C. The Idanha, Soda Springs.

D. The Northside Inn.

E. Hotel Boise.

4). What got a funeral in Wallace in 1991?

A. A jackass.

B. A mint condition ’34 Ford.

C. A Pulaski.

D. A stoplight.

E. A stop sign.

5) How did “melon gravel” get its name?

A. Named in a scientific paper.

B. Inspired by a Stinker Station sign.

C. Because it looks like petrified watermelons.

D. All of the above.

Answers

1, C

2, E

3, A

4, C

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on January 30, 2019 04:00