Rick Just's Blog, page 212

December 29, 2018

Mr. and Mrs. Yakima Cunnutt

Yakima Cunnutt is a famous rodeo rider that I’ve talked about before. Today, I’m going to focus on the brief period when there was a Mrs. Yakima Cunnutt.

Katherine “Kitty” Wilks was born in New York City in 1899. City-born, she was a cowgirl extraordinaire. She was the All-Around Champion Cowgirl at the Pendleton Round-Up in 1916. That’s where she met Yakima. They were married a year later in Kalispell, Montana.

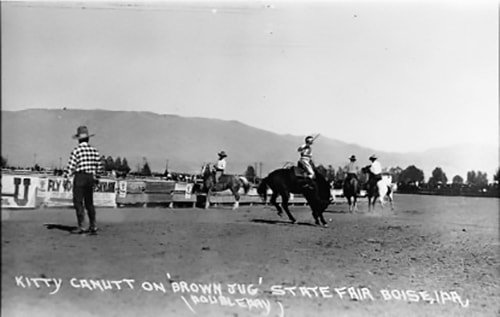

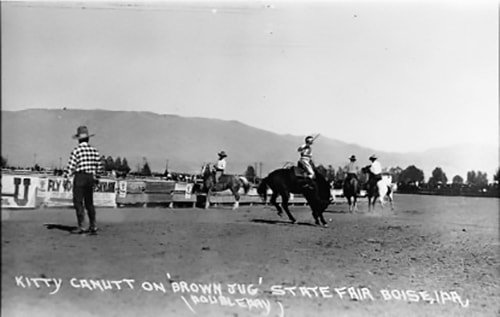

In 1917, when Mr. and Mrs. Cannutt came to compete in the state fair rodeo in Boise, in was a big deal. Yakima had just won his first of four All-Around Cowboy crowns at Pendleton.

Yakima didn’t do so well, but Mrs. Yakima, as she was sometimes called, won the cowgirls’ bucking contest and came in second in the women’s half mile race. That was in September. In October, the pair went to Weiser.

At the Weiser Annual Harvest Carnival and Oregon Trail Round-up. Frank McCarroll of Boise broke his arm while “saddling a wild broncho for Kittie Wilkes Cannutt,” according to the Idaho Statesman. Yakima “made two splendid efforts without success and suffered a nasty spill in front of the grandstands” while trying to bulldog a steer. None of the cowboys got one down that day, including Frank McCarroll who competed with his left arm in splints.

Yakima was down again when, “In the bucking horse contest Yakima Cannutt, who won the championship at Pendelton a few days ago had a bad fall when Ontario, the horse he was riding, fell. Cannutt came up with the animal, however, and finished his ride in splendid form.”

The marriage of Yakima and Kitty didn’t last long. They divorced in 1920. But In 1921 at the state fair rodeo Kitty Cannutt was still using the surname, and she was a sensation in the women’s relay race. But it was another woman who had the fans on their feet. With the subhead “Plucky Girl Refuses to be Invalid” the story in the Statesman said, “Lorena Trickey set herself square with the crowd when, after being badly injured when her horse crashed into the grandstand fence, she ran away from the Red Cross attendants and in a thrilling climax, nosed out Kitty Cannutt in the cowgirl’s Roman race amid the wild cheers of the grandstand.”

On the final day of the 1921 rodeo, the paper reported that, “With the attendance swelled by what looked like all the school children in the world, the Idaho state fair’s roundup finished Friday afternoon with some of the most exciting events of the week. Fair weather put the crowd in a jovial and ‘peppy’ mood.”

“Yak” Cunnutt took “first coin” in bulldogging ($400), with Frank McCarroll of broken arm fame coming in second. Kitty had to settle for third in the relay standings.

Kitty Cunnutt was sometimes called the “Diamond Girl” or “Diamond Kitty.” Why? Because she had a diamond set in one front tooth. It was flashy, and it was readily pawned when Kitty needed some cash.

Kitty Cunnutt remarried in 1923 and dropped out of public life. Yakima got into film-making as a stuntman, and became easily the most famous of that rough breed. He won a special Oscar in 1967—the only stuntman ever to receive one—and was inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1975.

Cannutt may be most famous for directing the chariot scenes in Ben Hur. His son, Joe Cannutt, was the stuntman injured during the filming of one of the scenes. And, no, there wasn’t anyone killed making that movie, though rumors persist.

Note that sources can’t settle on the spelling of some of the names, Kitty, Kittie, Katy, Wilks, Wilkes, Cannutt and Canutt. I’ve just gone with what was reported during the Idaho rodeos.

Photos:

Kitty Cannutt on Winnemucca in Rawlins, Wyoming in 1919. Library of Congress photo.

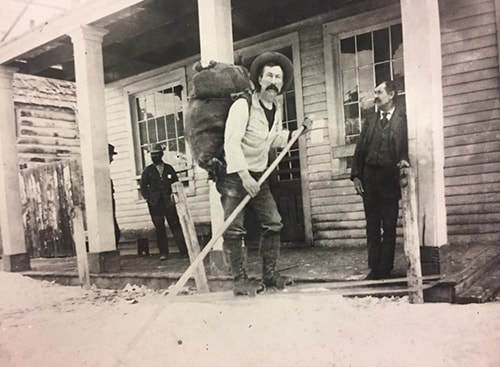

Yakima Cunnutt bulldogging at the Weiser Round-Up in 1895. Photo from the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Katherine “Kitty” Wilks was born in New York City in 1899. City-born, she was a cowgirl extraordinaire. She was the All-Around Champion Cowgirl at the Pendleton Round-Up in 1916. That’s where she met Yakima. They were married a year later in Kalispell, Montana.

In 1917, when Mr. and Mrs. Cannutt came to compete in the state fair rodeo in Boise, in was a big deal. Yakima had just won his first of four All-Around Cowboy crowns at Pendleton.

Yakima didn’t do so well, but Mrs. Yakima, as she was sometimes called, won the cowgirls’ bucking contest and came in second in the women’s half mile race. That was in September. In October, the pair went to Weiser.

At the Weiser Annual Harvest Carnival and Oregon Trail Round-up. Frank McCarroll of Boise broke his arm while “saddling a wild broncho for Kittie Wilkes Cannutt,” according to the Idaho Statesman. Yakima “made two splendid efforts without success and suffered a nasty spill in front of the grandstands” while trying to bulldog a steer. None of the cowboys got one down that day, including Frank McCarroll who competed with his left arm in splints.

Yakima was down again when, “In the bucking horse contest Yakima Cannutt, who won the championship at Pendelton a few days ago had a bad fall when Ontario, the horse he was riding, fell. Cannutt came up with the animal, however, and finished his ride in splendid form.”

The marriage of Yakima and Kitty didn’t last long. They divorced in 1920. But In 1921 at the state fair rodeo Kitty Cannutt was still using the surname, and she was a sensation in the women’s relay race. But it was another woman who had the fans on their feet. With the subhead “Plucky Girl Refuses to be Invalid” the story in the Statesman said, “Lorena Trickey set herself square with the crowd when, after being badly injured when her horse crashed into the grandstand fence, she ran away from the Red Cross attendants and in a thrilling climax, nosed out Kitty Cannutt in the cowgirl’s Roman race amid the wild cheers of the grandstand.”

On the final day of the 1921 rodeo, the paper reported that, “With the attendance swelled by what looked like all the school children in the world, the Idaho state fair’s roundup finished Friday afternoon with some of the most exciting events of the week. Fair weather put the crowd in a jovial and ‘peppy’ mood.”

“Yak” Cunnutt took “first coin” in bulldogging ($400), with Frank McCarroll of broken arm fame coming in second. Kitty had to settle for third in the relay standings.

Kitty Cunnutt was sometimes called the “Diamond Girl” or “Diamond Kitty.” Why? Because she had a diamond set in one front tooth. It was flashy, and it was readily pawned when Kitty needed some cash.

Kitty Cunnutt remarried in 1923 and dropped out of public life. Yakima got into film-making as a stuntman, and became easily the most famous of that rough breed. He won a special Oscar in 1967—the only stuntman ever to receive one—and was inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in 1975.

Cannutt may be most famous for directing the chariot scenes in Ben Hur. His son, Joe Cannutt, was the stuntman injured during the filming of one of the scenes. And, no, there wasn’t anyone killed making that movie, though rumors persist.

Note that sources can’t settle on the spelling of some of the names, Kitty, Kittie, Katy, Wilks, Wilkes, Cannutt and Canutt. I’ve just gone with what was reported during the Idaho rodeos.

Photos:

Kitty Cannutt on Winnemucca in Rawlins, Wyoming in 1919. Library of Congress photo.

Yakima Cunnutt bulldogging at the Weiser Round-Up in 1895. Photo from the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Published on December 29, 2018 04:00

December 28, 2018

That Beautiful Oakley Stone

If you’ve seen a few fireplaces in Idaho, you’ve likely seen Oakley Stone. Beginning in the late 1940s the rock mined nearly Oakley, Idaho in the Albion Mountains became a popular building material for entryways, home veneers, and fireplaces. Geologists know it as micaceous quartzite or Idaho quartzite. Oakley Stone is a trade name.

Oakley stone is popular in the U.S., Canada, and even in Europe, because of its range of colors, from silver to gold and everything in between, but also because it is efficient. It can be split much thinner than competing rock from other quarries. A ton of Oakley Stone can cover 250 to 300 feet, while a ton of other stone veneers can cover 60 feet or less.

Oakley Stone was formed over the ages when layers of clay alternating with layers rich in quartz, compressed together. According to Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology , the alternating quartz-rich layers were flattened by the pressure so that the porosity of the material was removed and the quartz grains formed an interlocking mosaic.

The quarries for the stone are about halfway up Middle Mountain where they can dig through a shallow layer of dirt to access the tilted layers of sedimentary rock. It’s mostly hand work, chiseling along the front edge of the rock to break away plates as thin as a quarter inch and up to 4 inches thick. The plates can be as big as eight feet in diameter, but are usually broken into much smaller pieces. Once on site, the stone is easy to work and shape.

Frank Lloyd Wright specified the stone for the interior and exterior of Teater’s Knoll, near Hagerman. The home was built for artist Archie Teater and is the only one in Idaho designed for a particular site by the famous architect. The photo, courtesy of Henry Whiting, shows Kent Hale’s exterior rock work on the building.

Oakley stone is popular in the U.S., Canada, and even in Europe, because of its range of colors, from silver to gold and everything in between, but also because it is efficient. It can be split much thinner than competing rock from other quarries. A ton of Oakley Stone can cover 250 to 300 feet, while a ton of other stone veneers can cover 60 feet or less.

Oakley Stone was formed over the ages when layers of clay alternating with layers rich in quartz, compressed together. According to Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology , the alternating quartz-rich layers were flattened by the pressure so that the porosity of the material was removed and the quartz grains formed an interlocking mosaic.

The quarries for the stone are about halfway up Middle Mountain where they can dig through a shallow layer of dirt to access the tilted layers of sedimentary rock. It’s mostly hand work, chiseling along the front edge of the rock to break away plates as thin as a quarter inch and up to 4 inches thick. The plates can be as big as eight feet in diameter, but are usually broken into much smaller pieces. Once on site, the stone is easy to work and shape.

Frank Lloyd Wright specified the stone for the interior and exterior of Teater’s Knoll, near Hagerman. The home was built for artist Archie Teater and is the only one in Idaho designed for a particular site by the famous architect. The photo, courtesy of Henry Whiting, shows Kent Hale’s exterior rock work on the building.

Published on December 28, 2018 04:00

December 27, 2018

Boise's "Beaver Dick"

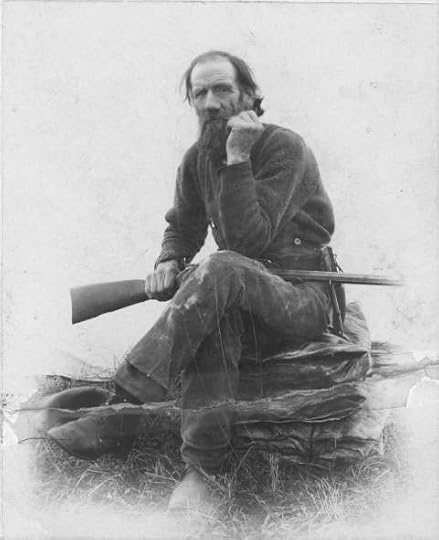

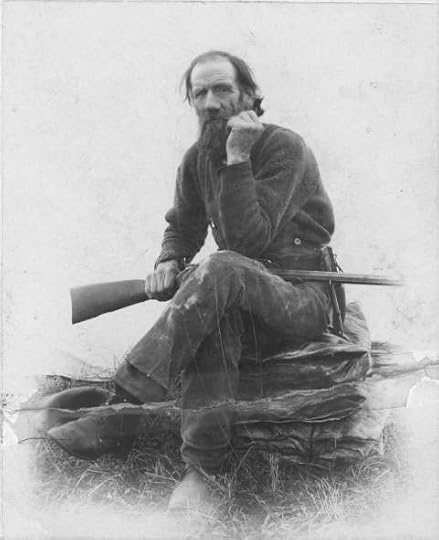

Richard “Beaver Dick” Leigh is well known in eastern Idaho history. He was a mountain man in the waning days of the fur trade, thus his self-imposed nickname. When the Hayden Expedition needed a guide for their famous exploration of the Yellowstone country, it was Beaver Dick they chose. Leigh Lake in Grand Teton National Park is named for him, while Jenny Lake, at the foot of the Tetons, honors his first wife, an Eastern Shoshone woman.

I wrote about Beaver Dick’s encounter with Theodore Roosevelt in an earlier post. Today, I’m going to tell you a bit about a little-known part of his life.

Richard Leigh, born in Manchester, England in 1831, came to what would become Idaho in the late 1840s. The biography Beaver Dick, The Honor and The Heartbreak , written by his great grandson William Leigh Thompson and Thompson’s wife Edith M. Schultz Thompson, does not mention his time in the Boise Valley. For the best account of that brief period in his life we turn to the diary of Charles Teeter.

In 1863, he wrote, “We were the first to cross the (Boise) river on a new ferry just constructed by an old mountaineer called Beaver Dick, consequently the ferry was to bear that name. Beaver Dick himself, accompanied by two or three of his men, brought over the ferry boat, and we were soon safely landed on the other side. Here we spent the night and as Beaver Dick was the first man we had seen who had visited the Boise gold mines, we had many questions to ask concerning them.”

It’s worth noting that the “old mountaineer” was 32 at the time. Living rough ages one, apparently.

Beaver Dick’s Ferry operated in 1863 and 1864 near where the Crow Inn was for many years on Warm Springs Boulevard, just west of Highway 21. The historical marker at the site says the following:

“In 1863 and 1864, overland packers hauling supplies from Salt Lake City to Idaho City crossed here and took a direct route northward to More’s Creek.

“They cut a steep grade from the Oregon Trail down to Beaver Dick’s Ferry, which served as a crossing only a short distance below here. After gold rush excitement ended, Idaho City traffic came on through Boise and used a toll road further north to Boise Basin.”

Richard "Beaver Dick" Leigh.

Richard "Beaver Dick" Leigh.

I wrote about Beaver Dick’s encounter with Theodore Roosevelt in an earlier post. Today, I’m going to tell you a bit about a little-known part of his life.

Richard Leigh, born in Manchester, England in 1831, came to what would become Idaho in the late 1840s. The biography Beaver Dick, The Honor and The Heartbreak , written by his great grandson William Leigh Thompson and Thompson’s wife Edith M. Schultz Thompson, does not mention his time in the Boise Valley. For the best account of that brief period in his life we turn to the diary of Charles Teeter.

In 1863, he wrote, “We were the first to cross the (Boise) river on a new ferry just constructed by an old mountaineer called Beaver Dick, consequently the ferry was to bear that name. Beaver Dick himself, accompanied by two or three of his men, brought over the ferry boat, and we were soon safely landed on the other side. Here we spent the night and as Beaver Dick was the first man we had seen who had visited the Boise gold mines, we had many questions to ask concerning them.”

It’s worth noting that the “old mountaineer” was 32 at the time. Living rough ages one, apparently.

Beaver Dick’s Ferry operated in 1863 and 1864 near where the Crow Inn was for many years on Warm Springs Boulevard, just west of Highway 21. The historical marker at the site says the following:

“In 1863 and 1864, overland packers hauling supplies from Salt Lake City to Idaho City crossed here and took a direct route northward to More’s Creek.

“They cut a steep grade from the Oregon Trail down to Beaver Dick’s Ferry, which served as a crossing only a short distance below here. After gold rush excitement ended, Idaho City traffic came on through Boise and used a toll road further north to Boise Basin.”

Richard "Beaver Dick" Leigh.

Richard "Beaver Dick" Leigh.

Published on December 27, 2018 04:00

December 26, 2018

Finding Tresore's Grave

It wasn’t unusual for me to be picking my way across the backs of downed giants, jumping little creeks, and seeking picturesque shafts of light streaming through the cedars. I’d done it many times along the shores of Priest Lake, looking for that picture that would transport the viewer to that same spot to experience my awe of the big trees.

I was the communication chief for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and part of that job was to serve as photographer of the parks. I had my favorite vantage point in each park where I could catch a sunrise, or the certain shadow of a dune. At Priest Lake the cedar groves were difficult to capture; their enormity and the cathedral-like nature of the forest they formed did not easily fit into an eyepiece.

That day I found a newly downed cedar, roots pointing into the air, still clinging to chunks of earth that had served the tree for at least a century. I walked the trunk toward those roots and looked through them, down to the shallow hole they had left behind and to the grassy area just beyond. There was a familiar formation of rocks, 13 stones in the shape of a cross, placed years before at the foot of a much younger tree.

I knew at once what it was. This was a part of the park known as Shipman Point, named after Nell Shipman, silent movie star who had her own movie studio in these woods. She had likely placed those stones there herself, in memory of Tresore, her great Dane.

Tresore was a movie star himself. He had played a feature role in one of Shipman’s movies, Back to God’s Country, filmed in 1919 in Canada. Shipman adored animals and was an early advocate for their humane treatment in films. She had a menagerie with her at Priest Lake, including Brownie the Bear, Barney the Elk, cougar, deer, sled dogs, and others.

In July, 1923, someone poisoned many of those animals, including Tresore. Shipman always suspected her landlord, to whom she owed money, had been the culprit. She mourned the loss of her Dane and memorialized him with these words: “Here lies Champion Great Dane Tresore, an artist, a soldier, and a gentleman. Killed July 17 by the cowardly hand of a human cur. He died as he lived, protecting his mistress and her property.”

What Shipman could not have known was that Tresore, in his death, played a huge part in the revival of interest in Shipman’s movies some 60 years later. A BSU professor named Tom Trusky ran across an essay she had written about the poisoning of Tresore in the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. He decided to find out more about Shipman. That led him down a path on which he discovered and restored every movie she ever made, and oversaw the publication of Shipman’s autobiography. Interest in her work as a pioneer woman in films remains high today because of Tom’s efforts.

Park rangers at Priest Lake, and some locals, knew where Tresore’s grave was long before I stumbled across it, of course. For me, my personal discovery came just a few months after my friend Tom’s death. It was a quirk he would have appreciated. He would have called it “a little treat.”

I was the communication chief for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and part of that job was to serve as photographer of the parks. I had my favorite vantage point in each park where I could catch a sunrise, or the certain shadow of a dune. At Priest Lake the cedar groves were difficult to capture; their enormity and the cathedral-like nature of the forest they formed did not easily fit into an eyepiece.

That day I found a newly downed cedar, roots pointing into the air, still clinging to chunks of earth that had served the tree for at least a century. I walked the trunk toward those roots and looked through them, down to the shallow hole they had left behind and to the grassy area just beyond. There was a familiar formation of rocks, 13 stones in the shape of a cross, placed years before at the foot of a much younger tree.

I knew at once what it was. This was a part of the park known as Shipman Point, named after Nell Shipman, silent movie star who had her own movie studio in these woods. She had likely placed those stones there herself, in memory of Tresore, her great Dane.

Tresore was a movie star himself. He had played a feature role in one of Shipman’s movies, Back to God’s Country, filmed in 1919 in Canada. Shipman adored animals and was an early advocate for their humane treatment in films. She had a menagerie with her at Priest Lake, including Brownie the Bear, Barney the Elk, cougar, deer, sled dogs, and others.

In July, 1923, someone poisoned many of those animals, including Tresore. Shipman always suspected her landlord, to whom she owed money, had been the culprit. She mourned the loss of her Dane and memorialized him with these words: “Here lies Champion Great Dane Tresore, an artist, a soldier, and a gentleman. Killed July 17 by the cowardly hand of a human cur. He died as he lived, protecting his mistress and her property.”

What Shipman could not have known was that Tresore, in his death, played a huge part in the revival of interest in Shipman’s movies some 60 years later. A BSU professor named Tom Trusky ran across an essay she had written about the poisoning of Tresore in the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. He decided to find out more about Shipman. That led him down a path on which he discovered and restored every movie she ever made, and oversaw the publication of Shipman’s autobiography. Interest in her work as a pioneer woman in films remains high today because of Tom’s efforts.

Park rangers at Priest Lake, and some locals, knew where Tresore’s grave was long before I stumbled across it, of course. For me, my personal discovery came just a few months after my friend Tom’s death. It was a quirk he would have appreciated. He would have called it “a little treat.”

Published on December 26, 2018 04:00

December 25, 2018

A Look at Christmas Past

Link to my Idaho Press column.

https://www.idahopress.com/community/...

https://www.idahopress.com/community/...

Published on December 25, 2018 07:40

December 24, 2018

That Weird Idaho Shark

Why don’t we have a state shark? Just asking. We have a state amphibian, a state bird, a state fish, a state flower, a state fruit, a state gem, a state horse, a state insect, a state raptor, a state tree, and a state vegetable (any guesses?). But, sadly, no state shark. Now, the picky readers out there will point out that to have a state shark, we’d have to have a shark in the state. Ha! I have you there.

True, it’s a fossil shark, but there’s precedent for that. Idaho has a state fossil, the Hagerman Horse. The shark I’m talking about is Helicoprion, which once swam the oceans over what is now Soda Springs. “Once” was about 250 million years ago.

I’ve seen the famous fossils. Every time I’ve looked at them they puzzled me. I’m not alone. They puzzle scientists, too. Sharks don’t fossilize well because their skeletons are made of cartilage. Shark teeth, on the other hand, can hang around for millennia. So it is with the Helicoprion. All we have to prove that it once existed are teeth. But those teeth are so weird. They make up a spiral with small teeth in the center growing geometrically until those on the outer edge become large (picture, top).

With just those buzz-saw teeth to work from, scientists have speculated for years on what the shark would have looked like. Were the teeth in the front of its mouth? In the back? Were they down its throat somehow?

In 2013 an international team of paleontologists, including Professor Leif Tapanila of the Idaho Museum of Natural History and Idaho State University published a paper about the shark in the journal Biology Letters, describing a rare fossil specimen that contained enough cartilage to give scientists a better idea of the creature’s jaw configuration. The image, from that publication, shows several previous depictions above the larger version that their findings describe.

Cute, huh? Even if you’d pass on the state shark idea, think of the mascot possibilities! Soda Springs Cardinals, have you thought of this?

True, it’s a fossil shark, but there’s precedent for that. Idaho has a state fossil, the Hagerman Horse. The shark I’m talking about is Helicoprion, which once swam the oceans over what is now Soda Springs. “Once” was about 250 million years ago.

I’ve seen the famous fossils. Every time I’ve looked at them they puzzled me. I’m not alone. They puzzle scientists, too. Sharks don’t fossilize well because their skeletons are made of cartilage. Shark teeth, on the other hand, can hang around for millennia. So it is with the Helicoprion. All we have to prove that it once existed are teeth. But those teeth are so weird. They make up a spiral with small teeth in the center growing geometrically until those on the outer edge become large (picture, top).

With just those buzz-saw teeth to work from, scientists have speculated for years on what the shark would have looked like. Were the teeth in the front of its mouth? In the back? Were they down its throat somehow?

In 2013 an international team of paleontologists, including Professor Leif Tapanila of the Idaho Museum of Natural History and Idaho State University published a paper about the shark in the journal Biology Letters, describing a rare fossil specimen that contained enough cartilage to give scientists a better idea of the creature’s jaw configuration. The image, from that publication, shows several previous depictions above the larger version that their findings describe.

Cute, huh? Even if you’d pass on the state shark idea, think of the mascot possibilities! Soda Springs Cardinals, have you thought of this?

Published on December 24, 2018 04:00

December 23, 2018

Now, for Something Completely Different

Today I’m going to step away from my usual post about Idaho History to recognize someone who contributes much to these missives. My wife, Rinda Just, reads and edits every article before I post it. She’s a “recovering” attorney, as she likes to say, and has a great eye for detail. On many occasions she has caught blunders that would have been embarrassing for me. Rinda is more than a proofreader, though. She’s my first audience and one that will hesitate not a trice to tell me if something doesn’t make sense or is just plain boring. Like me, she’s an Idaho native who knows the state’s history well, so not much gets past her.

Today is our 42nd wedding anniversary. I just wanted to acknowledge the love of my life.

Today is our 42nd wedding anniversary. I just wanted to acknowledge the love of my life.

Published on December 23, 2018 04:00

December 22, 2018

The Post Register

The Post Register is one of Idaho’s more important newspapers, and one with a long history, tracing its roots back to 1880. The newspaper has published in Idaho Falls for most of that time, but it didn’t start out there. It started in Blackfoot, as the Blackfoot Register.

Blackfoot was the terminus of the railroad in 1880 and probably seemed to publisher Edward Wheeler the better bet for starting a newspaper than Eagle Rock, 25 miles to the north. Eagle Rock would later become Idaho Falls, and by far the larger city, but in 1880 it didn’t amount to much. It had a saloon, a store, and Matt Taylor’s toll bridge. Blackfoot, meanwhile, had a café, hotel, four general stores, four saloons, two blacksmith shops, a wagon shop, a lumber yard, a doctor, and even a jewelry store. It was also, at the time, the most populated city in Idaho Territory. Newspapers run on advertising, so starting one in the comparatively booming City of Blackfoot was the easy choice.

And, make no mistake, advertising was top of mind for Mr. Wheeler. In the first edition of the Blackfoot Register he wrote, “We have… one main object in view, and that is to secure as large an amount of the filthy lucre as possible.”

Wheeler did well enough in Blackfoot for the more than three years he operated there. He plunged into local political issues, championed the building of the city’s first school, and even campaigned to make Blackfoot the territory’s new capital. But lucre moved north and so did the paper.

By 1884 the railroad line had stretched to Eagle Rock and established its headquarters there. Settlers began pouring in. Wheeler pulled up stakes and moved his operation to Eagle Rock where the newspaper began calling itself the Idaho Register.

I’ll write more about the Post Register in later posts, relying as I did for much of this post on William Hathaway’s fascinating book, Images of America, Idaho Falls Post Register , published by Arcadia Publishing.

Blackfoot was the terminus of the railroad in 1880 and probably seemed to publisher Edward Wheeler the better bet for starting a newspaper than Eagle Rock, 25 miles to the north. Eagle Rock would later become Idaho Falls, and by far the larger city, but in 1880 it didn’t amount to much. It had a saloon, a store, and Matt Taylor’s toll bridge. Blackfoot, meanwhile, had a café, hotel, four general stores, four saloons, two blacksmith shops, a wagon shop, a lumber yard, a doctor, and even a jewelry store. It was also, at the time, the most populated city in Idaho Territory. Newspapers run on advertising, so starting one in the comparatively booming City of Blackfoot was the easy choice.

And, make no mistake, advertising was top of mind for Mr. Wheeler. In the first edition of the Blackfoot Register he wrote, “We have… one main object in view, and that is to secure as large an amount of the filthy lucre as possible.”

Wheeler did well enough in Blackfoot for the more than three years he operated there. He plunged into local political issues, championed the building of the city’s first school, and even campaigned to make Blackfoot the territory’s new capital. But lucre moved north and so did the paper.

By 1884 the railroad line had stretched to Eagle Rock and established its headquarters there. Settlers began pouring in. Wheeler pulled up stakes and moved his operation to Eagle Rock where the newspaper began calling itself the Idaho Register.

I’ll write more about the Post Register in later posts, relying as I did for much of this post on William Hathaway’s fascinating book, Images of America, Idaho Falls Post Register , published by Arcadia Publishing.

Published on December 22, 2018 04:00

December 21, 2018

Sheepherder Bill's Explosive Story

When “Sheepherder Bill” Borden made the paper, it was rarely good news. In 1902, the June 27 issue of the Idaho Statesman ran the following blurb, which was typical of the mentions about the man: “Bill Borden, better known as Sheepherder Bill, was in police court yesterday on the usual charge of being drunk. He was fined and costed to the amount of $5 and not having the coin, he will languish in the Bastille.”

Borden was a well-known miner in the Thunder Mountain region. He was also well known as a packer, carrying the heaviest backpacks of mail between Warrens and Thunder Mountain. And he was well known as a moonshiner. In his youth he was an ordained minister. Did you notice anything about sheep in all those well-knowns? Why he was called “Sheepherder Bill” is a minor mystery.

It was bad news, again, in July of 1905. It seems that Borden and a man named Barnum were curious about whether or not a piece of fuse was still good. One of them lit it and, yes, it was good. The burning fuse was tossed unartfully away, landing on a box of dynamite. The resulting explosion killed Barnum, and badly injured Borden. The first reports of the incident listed, “Sheepherder Bill, rock blown into side; probably fatal.”

The second report, a couple of days later, credited Mrs. Carl Brown with saving his life.

The best news I found about Borden in early papers was a story in the Statesman in 1907 when he was said to have found a “rich gold find mysteriously near Meadows.”

The bad news held off for a number of years, but the final report was of Sheepherder Bill’s death by a second explosion. His homemade still had blown up inside his cabin in 1932. He had perished in the resulting fire.

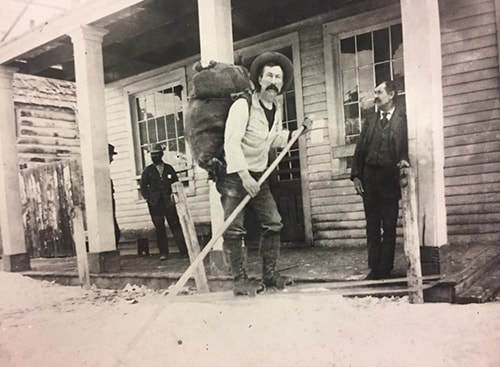

Sheepherder Bill in 1897 on skis, carrying his famous backpack. Bill Patterson, storekeeper and postmaster is to his right. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Sheepherder Bill in 1897 on skis, carrying his famous backpack. Bill Patterson, storekeeper and postmaster is to his right. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Borden was a well-known miner in the Thunder Mountain region. He was also well known as a packer, carrying the heaviest backpacks of mail between Warrens and Thunder Mountain. And he was well known as a moonshiner. In his youth he was an ordained minister. Did you notice anything about sheep in all those well-knowns? Why he was called “Sheepherder Bill” is a minor mystery.

It was bad news, again, in July of 1905. It seems that Borden and a man named Barnum were curious about whether or not a piece of fuse was still good. One of them lit it and, yes, it was good. The burning fuse was tossed unartfully away, landing on a box of dynamite. The resulting explosion killed Barnum, and badly injured Borden. The first reports of the incident listed, “Sheepherder Bill, rock blown into side; probably fatal.”

The second report, a couple of days later, credited Mrs. Carl Brown with saving his life.

The best news I found about Borden in early papers was a story in the Statesman in 1907 when he was said to have found a “rich gold find mysteriously near Meadows.”

The bad news held off for a number of years, but the final report was of Sheepherder Bill’s death by a second explosion. His homemade still had blown up inside his cabin in 1932. He had perished in the resulting fire.

Sheepherder Bill in 1897 on skis, carrying his famous backpack. Bill Patterson, storekeeper and postmaster is to his right. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Sheepherder Bill in 1897 on skis, carrying his famous backpack. Bill Patterson, storekeeper and postmaster is to his right. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on December 21, 2018 04:00

December 20, 2018

Idaho's Poets Laureate

I’m helping produce an interpretive handout for use in the historic home once occupied by my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid. She was a well-known writer in the northwest when she was alive. A family member mentioned that she had been the poet laureate of Idaho. I didn’t think so, because it was the kind of thing I would remember. So, that sent me down a poet laureate path.

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom (photo) of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominated a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to present)

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom (photo) of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominated a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to present)

Published on December 20, 2018 04:00