Rick Just's Blog, page 215

November 29, 2018

Those Elusive Chinese Tunnels

I enter the Chinese tunnels of Boise with some trepidation, knowing that opinions are strong and documentation is weak. Actually, let’s say I enter the debate, since the tunnels themselves are so elusive.

There were many newspaper mentions of tunnels built by Chinese laborers in the late 1800s. They weren’t in Boise, though. The stories that mentioned the tunnels were about mining in the mountains.

Boise had a substantial Chinese population in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but did they build tunnels? If they didn’t, where did the myth come from? There were Chinese tunnels, most famously in San Francisco. Portland had a network called the Shanghai tunnels. Los Angeles had Chinese tunnels. Did Boise?

I searched for mention of them in digital scans of the Statesman from those years and turned up nothing. The first mention I found of Chinese tunnels in the Statesman was in a column by Dick d’Easum in 1961. He was addressing the “myth” of the tunnels and speculating on how it got started. There were underground rooms that led off basements in the Chinese section of the city. It was said that illicit activities sometimes occurred there, such as the smoking of opium. What did not seem to be the case was that those rooms connected in a network beneath the city that would allow someone to enter at one point and pop up blocks away.

One possible source of the tunnel stories was the prevalence of unauthorized sewers. Today we hear of sinkholes opening up and swallowing cars. In Boise in the 1880s such sinkholes could make horses disappear. Dick d’Easum told of a wagon loaded with merchandise that suddenly sank half out of sight on Idaho Street. The struggling team of horses were soon pulled into the widening hole. A Chinese sewer was the cause. Once the team and wagon were extricated it was filled in. The city engineer found more unauthorized sewers and the city council decreed that they all be filled in.

Over the years Boise has had countless street and utility projects, not to mention the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of numerous buildings. No Chinese tunnels have been found. Yet, the myth persists. That’s partly because one can’t prove a negative such as this. There MIGHT be a system of tunnels somewhere that have yet to be found. Dig deeper, maybe. Great Uncle Hyrum said he saw them.

By the way, the graphic is supposed to be “China Tunnel” in pinyin, if you can trust those internet translation services.

There were many newspaper mentions of tunnels built by Chinese laborers in the late 1800s. They weren’t in Boise, though. The stories that mentioned the tunnels were about mining in the mountains.

Boise had a substantial Chinese population in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but did they build tunnels? If they didn’t, where did the myth come from? There were Chinese tunnels, most famously in San Francisco. Portland had a network called the Shanghai tunnels. Los Angeles had Chinese tunnels. Did Boise?

I searched for mention of them in digital scans of the Statesman from those years and turned up nothing. The first mention I found of Chinese tunnels in the Statesman was in a column by Dick d’Easum in 1961. He was addressing the “myth” of the tunnels and speculating on how it got started. There were underground rooms that led off basements in the Chinese section of the city. It was said that illicit activities sometimes occurred there, such as the smoking of opium. What did not seem to be the case was that those rooms connected in a network beneath the city that would allow someone to enter at one point and pop up blocks away.

One possible source of the tunnel stories was the prevalence of unauthorized sewers. Today we hear of sinkholes opening up and swallowing cars. In Boise in the 1880s such sinkholes could make horses disappear. Dick d’Easum told of a wagon loaded with merchandise that suddenly sank half out of sight on Idaho Street. The struggling team of horses were soon pulled into the widening hole. A Chinese sewer was the cause. Once the team and wagon were extricated it was filled in. The city engineer found more unauthorized sewers and the city council decreed that they all be filled in.

Over the years Boise has had countless street and utility projects, not to mention the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of numerous buildings. No Chinese tunnels have been found. Yet, the myth persists. That’s partly because one can’t prove a negative such as this. There MIGHT be a system of tunnels somewhere that have yet to be found. Dig deeper, maybe. Great Uncle Hyrum said he saw them.

By the way, the graphic is supposed to be “China Tunnel” in pinyin, if you can trust those internet translation services.

Published on November 29, 2018 04:00

November 28, 2018

Air Mail

What most people remember about the first contract air mail service is that Leon D. Cuddeback landed one of Varney Airline’s mail service planes in Boise on April 6, 1926. Often lost in the telling was that it wasn’t Cuddeback, the company’s chief pilot, who was supposed to be on the run. The evening before the inaugural flight from Pasco, Washington was to take place, air mail pilots Joseph Taff and George Buck had engine trouble about five miles outside of Pasco. They were able to set the plane down without damage, but the engine issues put it out of commission.

The airplanes that were to be used for the route were brand new and had been delivered much later than planned. They should have had 25 to 50 hours of breaking-in flight on them before being put into service, but the deadline made that impossible.

With the plane in Washington out of business, Cuddeback flew a relief plane to Pasco, picked up the mail, and returned to Boise before flying on to Elko, Nevada on the three-city route. Meanwhile, Franklin Rose was set to fly to Boise from Elko the same day.

The April 7, 1926 edition of the Idaho Statesman had a picture on the front page of Cuddeback, Postmaster L.W. Thrailkill, and Boise Mayor Ern G. Eagleson with a bag of mail in front of a Varney airplane. But the headline that ran across all seven columns of the paper was “Aviator Missing on Night of Celebration.”

When darkness dropped over the new Boise Airport and Varney pilot Franklin Rose had yet to appear, search parties were immediately organized. Automobiles set out across the desert between Boise and Mountain Home and from Bruneau to the Nevada line. Word came that Rose had been spotted over Deep Creek and that there had been a terrible storm.

On April 8, the Statesman carried the good news that Rose had turned up after being missing for 24 hours. He had been blown off course by the storm and set the plane down in a freshly plowed field on the Earl Brace ranch, 65 miles south of Jordan Valley, Oregon. It was mired in deep mud, but undamaged. Rose had borrowed a horse from another local rancher and rode it 35 miles to the Prince Hardesty ranch where he found a phone and got a message to Boise.

The Statesman reported on April 18, that Rose, Cuddeback, and Taff had set out to retrieve the plane. They had left at four in the morning from Boise by automobile and found themselves trying to ford a flooding Owyhee County creek at 10 o’clock that night. The car bobbed out from under the men and started to float downstream. Somehow they got a rope on the vehicle and hauled it up onto the bank. They got the car running and set out, again, only to abandon the vehicle for good when the going got too muddy. They commandeered some horses to complete the trip, arriving finally at the Brace ranch at 4 pm the next day. Rose had been bucked off, suffering a sprained finger, but he was able to fly the plane back to Boise with Taff in the cargo box. Cuddeback stayed behind to disentangle the car.

Meanwhile, other Varney planes that were supposed to fly the new route kept dropping out of the sky with engine trouble. Service was spotty, at best. On April 11, Walter T. Varney petitioned the postal service for a 60-day postponement of his contract so that he could get the airplanes in better shape.

The solution to Varney’s problems seemed to be installing new, more powerful engines in the fleet of planes. The 200 HP engines, built by the Orville Wright company of Cleveland, were 83 percent more powerful than the Curtis engines that came originally with the planes.

Eventually they worked the bugs out, Varney Airlines built hangers in Boise and, in 1930 the company was acquired by the United Transport Corporation. United Airlines traces its beginnings to that purchase and considers Boise its original “home.”

Ed Cuddeback in front of a Varney Swallow, courtesy of the Ed Coates Collection.

Ed Cuddeback in front of a Varney Swallow, courtesy of the Ed Coates Collection.  The missing pilot, Franklin Rose.

The missing pilot, Franklin Rose.

The airplanes that were to be used for the route were brand new and had been delivered much later than planned. They should have had 25 to 50 hours of breaking-in flight on them before being put into service, but the deadline made that impossible.

With the plane in Washington out of business, Cuddeback flew a relief plane to Pasco, picked up the mail, and returned to Boise before flying on to Elko, Nevada on the three-city route. Meanwhile, Franklin Rose was set to fly to Boise from Elko the same day.

The April 7, 1926 edition of the Idaho Statesman had a picture on the front page of Cuddeback, Postmaster L.W. Thrailkill, and Boise Mayor Ern G. Eagleson with a bag of mail in front of a Varney airplane. But the headline that ran across all seven columns of the paper was “Aviator Missing on Night of Celebration.”

When darkness dropped over the new Boise Airport and Varney pilot Franklin Rose had yet to appear, search parties were immediately organized. Automobiles set out across the desert between Boise and Mountain Home and from Bruneau to the Nevada line. Word came that Rose had been spotted over Deep Creek and that there had been a terrible storm.

On April 8, the Statesman carried the good news that Rose had turned up after being missing for 24 hours. He had been blown off course by the storm and set the plane down in a freshly plowed field on the Earl Brace ranch, 65 miles south of Jordan Valley, Oregon. It was mired in deep mud, but undamaged. Rose had borrowed a horse from another local rancher and rode it 35 miles to the Prince Hardesty ranch where he found a phone and got a message to Boise.

The Statesman reported on April 18, that Rose, Cuddeback, and Taff had set out to retrieve the plane. They had left at four in the morning from Boise by automobile and found themselves trying to ford a flooding Owyhee County creek at 10 o’clock that night. The car bobbed out from under the men and started to float downstream. Somehow they got a rope on the vehicle and hauled it up onto the bank. They got the car running and set out, again, only to abandon the vehicle for good when the going got too muddy. They commandeered some horses to complete the trip, arriving finally at the Brace ranch at 4 pm the next day. Rose had been bucked off, suffering a sprained finger, but he was able to fly the plane back to Boise with Taff in the cargo box. Cuddeback stayed behind to disentangle the car.

Meanwhile, other Varney planes that were supposed to fly the new route kept dropping out of the sky with engine trouble. Service was spotty, at best. On April 11, Walter T. Varney petitioned the postal service for a 60-day postponement of his contract so that he could get the airplanes in better shape.

The solution to Varney’s problems seemed to be installing new, more powerful engines in the fleet of planes. The 200 HP engines, built by the Orville Wright company of Cleveland, were 83 percent more powerful than the Curtis engines that came originally with the planes.

Eventually they worked the bugs out, Varney Airlines built hangers in Boise and, in 1930 the company was acquired by the United Transport Corporation. United Airlines traces its beginnings to that purchase and considers Boise its original “home.”

Ed Cuddeback in front of a Varney Swallow, courtesy of the Ed Coates Collection.

Ed Cuddeback in front of a Varney Swallow, courtesy of the Ed Coates Collection.  The missing pilot, Franklin Rose.

The missing pilot, Franklin Rose.

Published on November 28, 2018 04:00

November 27, 2018

Who Built the Boise Airport?

Boise is proud of its airmail history. You probably already know that the first commercial air mail route flew between Boise, Pasco, Washington, and Elko, Nevada. Varney Airlines, the company that flew the route was based in Boise. United Airlines traces the beginning of their history to Varney.

There are a couple of things that are often left out of the story. First, there was one tiny hurdle Boise had to clear before air mail could happen. The city needed an airport. Second, the early days of air mail service along the three-city route could be kindly described as a fiasco.

Air mail service would begin in Boise on April 6, 1926. In January of that year, local citizens were just forming a committee to figure out how to build an airport. One might assume that the city council would be that committee, or designate its members, but there were issues that precluded that. The proposed airport site was south of the Boise River, just across from Julia Davis Park. That’s where BSU is today. In 1926, it wasn’t a part of the city. The city attorney advised the council that it couldn’t spend money outside the city limits, and it wasn’t clear they could spend money on an airport even if they annexed the land.

Did I mention that air mail service would begin on April 6? Somebody had to step up. The American Legion, which had engineers and builders and people used to giving orders following World War I, came forward to take on the task. The Boise Chamber of Commerce raised some money, and a call went out for volunteers—“Come with an axe and willing hands” FREE LUNCH.

The city council continued to debate the role the city would eventually play in paying for and operating the airport, but the American Legion charged ahead. When Leon D. Cuddeback, chief pilot for Varney, came to inspect the proposed airport site it had been pouring rain for almost 24 hours. Yet, the drainage looked good. He gave the project his thumbs up.

Cuddeback informed the Legion committee members that the planes his company would use for air mail could take off and land in 500 feet, but he said other planes the company would bring to the new airport would need more space. He recommended a 2,000-foot runway that would be “ample for any service.” But even before the landing strips were completed there was talk of eventually moving the airport up on the bench away from seasonal flooding and the occasional fog the river generated.

With the help of volunteers, service clubs, and the chamber of commerce, the American Legion got the job done. The airport was ready for air mail service to begin in April. Varney Airlines, as it turned out, wasn’t as ready as they thought they were. That story tomorrow.

There are a couple of things that are often left out of the story. First, there was one tiny hurdle Boise had to clear before air mail could happen. The city needed an airport. Second, the early days of air mail service along the three-city route could be kindly described as a fiasco.

Air mail service would begin in Boise on April 6, 1926. In January of that year, local citizens were just forming a committee to figure out how to build an airport. One might assume that the city council would be that committee, or designate its members, but there were issues that precluded that. The proposed airport site was south of the Boise River, just across from Julia Davis Park. That’s where BSU is today. In 1926, it wasn’t a part of the city. The city attorney advised the council that it couldn’t spend money outside the city limits, and it wasn’t clear they could spend money on an airport even if they annexed the land.

Did I mention that air mail service would begin on April 6? Somebody had to step up. The American Legion, which had engineers and builders and people used to giving orders following World War I, came forward to take on the task. The Boise Chamber of Commerce raised some money, and a call went out for volunteers—“Come with an axe and willing hands” FREE LUNCH.

The city council continued to debate the role the city would eventually play in paying for and operating the airport, but the American Legion charged ahead. When Leon D. Cuddeback, chief pilot for Varney, came to inspect the proposed airport site it had been pouring rain for almost 24 hours. Yet, the drainage looked good. He gave the project his thumbs up.

Cuddeback informed the Legion committee members that the planes his company would use for air mail could take off and land in 500 feet, but he said other planes the company would bring to the new airport would need more space. He recommended a 2,000-foot runway that would be “ample for any service.” But even before the landing strips were completed there was talk of eventually moving the airport up on the bench away from seasonal flooding and the occasional fog the river generated.

With the help of volunteers, service clubs, and the chamber of commerce, the American Legion got the job done. The airport was ready for air mail service to begin in April. Varney Airlines, as it turned out, wasn’t as ready as they thought they were. That story tomorrow.

Published on November 27, 2018 04:00

November 26, 2018

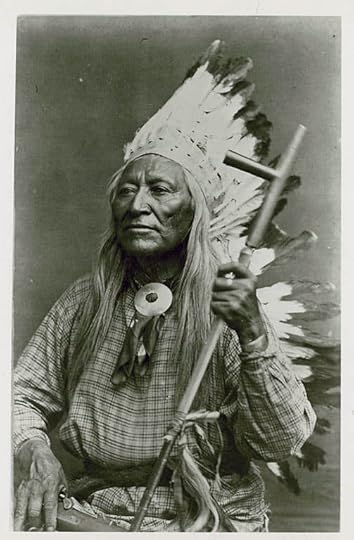

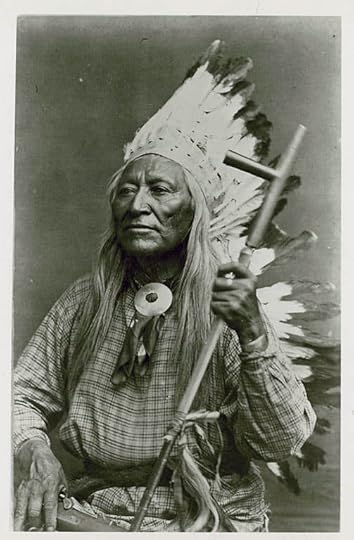

Chief Washakie

Back before there was an Idaho, or a Wyoming, or pick your state, there was a Shoshoni land that stretched irregularly from Death Valley north to where Salmon is today, and east into the Wind River Range. It encompassed much of southern Idaho and northern Utah.

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

Chief Washakie

Chief Washakie

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

Chief Washakie

Chief Washakie

Published on November 26, 2018 04:00

November 25, 2018

The Big Burn

The Great Fire of 1910, often called the Big Burn, was one of the seminal events in Idaho history, and changed the way foresters thought about fire.

I’ll give you a brief outline today, mostly because I ran across a series of exceptional photos on the Forest History Society site. For the complete story I recommend The Big Burn, by Timothy Egan.

The fire burned over two days, August 21 and 22 of 1910, incinerating 3 million acres in Washington, Montana, British Columbia, and Idaho. Even though fires have been growing in size in recent years, it remains the largest forest fire in the United States.

By mid-August that year there were more than a thousand fires burning in the drought-stricken Pacific Northwest. They started from a variety of sources including cinders from locomotives, campfires gone rogue, and lightening. Bad as that was, the multiple fires would become one big monster on August 20, when hurricane force winds blew through the region.

The Big Burn killed 87 people. To their peril, firefighters tried to stop it. An entire crew of 28 men lost their lives near Avery. In all, 78 firefighters perished. In desperation forest ranger Ed Pulaski led his 45-man crew into an abandoned mine tunnel to escape the flames. It was so hot and smoky in there that several men tried to go back outside. Pulaski pulled his gun on them to force them to stay. Five died in the tunnel, but the rest survived. The old War Eagle mine tunnel, south of Wallace, is now known as the Pulaski Tunnel, and is on the National Register of Historic Places. About a third of the town of Wallace was destroyed by the fire.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.

The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

I’ll give you a brief outline today, mostly because I ran across a series of exceptional photos on the Forest History Society site. For the complete story I recommend The Big Burn, by Timothy Egan.

The fire burned over two days, August 21 and 22 of 1910, incinerating 3 million acres in Washington, Montana, British Columbia, and Idaho. Even though fires have been growing in size in recent years, it remains the largest forest fire in the United States.

By mid-August that year there were more than a thousand fires burning in the drought-stricken Pacific Northwest. They started from a variety of sources including cinders from locomotives, campfires gone rogue, and lightening. Bad as that was, the multiple fires would become one big monster on August 20, when hurricane force winds blew through the region.

The Big Burn killed 87 people. To their peril, firefighters tried to stop it. An entire crew of 28 men lost their lives near Avery. In all, 78 firefighters perished. In desperation forest ranger Ed Pulaski led his 45-man crew into an abandoned mine tunnel to escape the flames. It was so hot and smoky in there that several men tried to go back outside. Pulaski pulled his gun on them to force them to stay. Five died in the tunnel, but the rest survived. The old War Eagle mine tunnel, south of Wallace, is now known as the Pulaski Tunnel, and is on the National Register of Historic Places. About a third of the town of Wallace was destroyed by the fire.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side. The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

Published on November 25, 2018 04:00

November 24, 2018

Pulling Hill

The Google Earth satellite photo of Pulling Hill on the northeast side of the Presto Bench a few miles outside of Firth looks a little like an art installation. Motorcycles installed it, for the most part. I helped with that as a kid. In the winter the hillsides were where everyone went to sleigh and sometimes snowmobile.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Published on November 24, 2018 04:00

November 23, 2018

The First Train in Boise

On September 3, 1887, an event took place in Boise that was worthy of a ribbon cutting and a parade. Neither happened because the arrival of the first train came as a bit of a surprise. The train moved slowly, because ties and rails were being laid just in front of it as the engine proceeded.

Even without a planned ceremony, Boiseans ginned up a celebration. Hundreds of them saw the train inching along and set out to greet it. Many jumped up on a flatcar (photo) to take that first slow ride into the depot. The Idaho Statesman reported that “On Sunday the road from town to the depot was lined with people nearly all day. The distance is about a mile, and the more fortunate rode in carriages, others in lumber wagons, and others on horseback, while hundreds of men, women and children walked over.”

Other Idaho communities had enjoyed railroad service for some time before the trains came to Boise. Financing was a hurdle. The Statesman explained why: “Boise is probably the best town, and contains as many wealthy people as any town between the Missouri and Columbia rivers, but the wealth of her citizens is not centered in a few individuals, but in many, and there is only a limited amount of ready money; hence the building of a railroad when only a quarter of a million or even one hundred and fifty thousand dollars is required, has to find its source and support among eastern capitalists.”

Mr. J. A. McGee was credited with the conception of the Idaho Central railroad. The paper reported that it was he who found that eastern money.

It wasn’t long before all the citizens of Boise were enjoying the benefits McGee’s vision. Yes, vegetables could be shipped out, and building supplies shipped in, and all manner of goods were made more readily available, but let’s talk entertainment!

Less than a month after the first train arrived, a four-block-long circus train pulled into the depot. Barrett’s Circus was the largest ever to visit Boise up to that time. The Statesman described the resulting parade with “six horse, four horse and two horse teams, well matched and in fine condition. They were escorted or rather interspersed with three bands of music. First, the brass band composed of white men, second, a colored man’s band, and lastly in the rear followed the far-screeching and terrific sounding steam calliope. The cages containing the lions, leopards and tigers had a man in each cage with the animals who appeared as unconcerned and as much at home as the animals in his cage… The elephants and camels preceded the calliope and the grinning lips of the camels would indicate, if the calliope wagon had been covered up, that they were singing the songs of the ancients in their march through Boise.” Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

Even without a planned ceremony, Boiseans ginned up a celebration. Hundreds of them saw the train inching along and set out to greet it. Many jumped up on a flatcar (photo) to take that first slow ride into the depot. The Idaho Statesman reported that “On Sunday the road from town to the depot was lined with people nearly all day. The distance is about a mile, and the more fortunate rode in carriages, others in lumber wagons, and others on horseback, while hundreds of men, women and children walked over.”

Other Idaho communities had enjoyed railroad service for some time before the trains came to Boise. Financing was a hurdle. The Statesman explained why: “Boise is probably the best town, and contains as many wealthy people as any town between the Missouri and Columbia rivers, but the wealth of her citizens is not centered in a few individuals, but in many, and there is only a limited amount of ready money; hence the building of a railroad when only a quarter of a million or even one hundred and fifty thousand dollars is required, has to find its source and support among eastern capitalists.”

Mr. J. A. McGee was credited with the conception of the Idaho Central railroad. The paper reported that it was he who found that eastern money.

It wasn’t long before all the citizens of Boise were enjoying the benefits McGee’s vision. Yes, vegetables could be shipped out, and building supplies shipped in, and all manner of goods were made more readily available, but let’s talk entertainment!

Less than a month after the first train arrived, a four-block-long circus train pulled into the depot. Barrett’s Circus was the largest ever to visit Boise up to that time. The Statesman described the resulting parade with “six horse, four horse and two horse teams, well matched and in fine condition. They were escorted or rather interspersed with three bands of music. First, the brass band composed of white men, second, a colored man’s band, and lastly in the rear followed the far-screeching and terrific sounding steam calliope. The cages containing the lions, leopards and tigers had a man in each cage with the animals who appeared as unconcerned and as much at home as the animals in his cage… The elephants and camels preceded the calliope and the grinning lips of the camels would indicate, if the calliope wagon had been covered up, that they were singing the songs of the ancients in their march through Boise.”

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

Published on November 23, 2018 04:00

November 22, 2018

Protest Road

If you’ve been reading these history posts for a while, you know that I’m interested in how things got their names. I’ve done posts on how the state got its name, where county names came from, and why cities in Idaho have their names. I’m even a proud member pf the Idaho Geographic Names Advisory Committee.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

Published on November 22, 2018 04:00

November 21, 2018

Freedom

It is difficult to pin the town of Freedom down. First, it crosses a lot of boundaries, two counties and two states. The states are Idaho and Wyoming, and the counties are Caribou (in Idaho) and Lincoln (Wyoming). Some even claim there is a part of Freedom in Bonneville County, Idaho. That seems a stretch, though official town boundaries could include some farmland reaching north into Bonneville, I suppose.

One might assume Freedom is a sprawling community given those geographic distinction. It is not. The total population of the combined community of Freedom, according to the 2010 census, was 210.

And, where is the “real” Freedom, Idaho or Wyoming? That’s a little slippery, too. In the early 1920s, postal authorities gave Freedom, Idaho the bad news that there was already another town named Freedom in Idaho, and it already had a post office. That town, south of Grangeville, is today known as Slate Creek. Sticklers about avoiding confusing addresses, the postal authorities suggested residents of the Caribou County Freedom find another name. They liked the name of their town, so their solution was simply to put the post office across the border in Wyoming, since there was only one Freedom there.

The residents of Freedom (Idaho and Wyoming) liked the name of their bisected town, partly because it was that bisection that historically gave some of them freedom. The town was originally established as a Mormon community in 1879. That was back when polygamy was a part of church doctrine. It was, however, illegal. The handy state border that ran through the middle of town gave practitioners of polygamy a chance to avoid arrest by stepping out of the jurisdiction of Idaho authorities into Wyoming.

Today, Freedom (the Wyoming version) is probably best known as the site of Freedom Arms, a manufacturer of some powerful pistols. Both Freedoms are located in Star Valley, a stunningly beautiful place.

One might assume Freedom is a sprawling community given those geographic distinction. It is not. The total population of the combined community of Freedom, according to the 2010 census, was 210.

And, where is the “real” Freedom, Idaho or Wyoming? That’s a little slippery, too. In the early 1920s, postal authorities gave Freedom, Idaho the bad news that there was already another town named Freedom in Idaho, and it already had a post office. That town, south of Grangeville, is today known as Slate Creek. Sticklers about avoiding confusing addresses, the postal authorities suggested residents of the Caribou County Freedom find another name. They liked the name of their town, so their solution was simply to put the post office across the border in Wyoming, since there was only one Freedom there.

The residents of Freedom (Idaho and Wyoming) liked the name of their bisected town, partly because it was that bisection that historically gave some of them freedom. The town was originally established as a Mormon community in 1879. That was back when polygamy was a part of church doctrine. It was, however, illegal. The handy state border that ran through the middle of town gave practitioners of polygamy a chance to avoid arrest by stepping out of the jurisdiction of Idaho authorities into Wyoming.

Today, Freedom (the Wyoming version) is probably best known as the site of Freedom Arms, a manufacturer of some powerful pistols. Both Freedoms are located in Star Valley, a stunningly beautiful place.

Published on November 21, 2018 04:00

November 20, 2018

More Plates

License plates are ubiquitous. Everyone who has a car, truck, or motorcycle in Idaho owns at least a couple of them. So why the heck would anyone collect them? Because they’re interesting, and because most of them get thrown away or recycled, so the surviving plates become rarer and rarer as their litter mates succumb. Yes, I just used “litter mates” to describe license plates. Maybe that’s a first and this post will become collectable.

I’m a very minor collector of license plates. I have about 40 or 50, mostly because I keep my personalized plates when it’s time to replace them. And I’m old. There’s that.

Collectors lust for one of Idaho’s first state plates, issued in 1913. There are only a couple of those still around. Idaho issued only single plates for automobiles in 1913 and 1914, ensuring a little extra rarity. Other rarities are early city plates issued by Hailey, Nampa, Payette, Weiser, Lewiston, and Boise, prior to 1913. According to Dan Smith, an acknowledged expert on Idaho license plates, only 19 of those are known to exist.

Did you know there were once hand-painted Idaho license plates? From 1913 to 1924 dealer plates were embossed with the words IDAHO DEALER, but there were no embossed numbers. Dealers had numbers painted on them by professionals. For a time, if you lost your license plate you would be issued a “flat” plate with no number on it, and you were expected to have your number painted on it by a professional. There are only a handful of those around anymore.

The county designators on plates have been around since 1932, but they weren’t all the familiar letter/number combination we see today. In 1932, for instance, Ada county was A1, while Lewis County was K4. It wasn’t until 1945 that the system we’re familiar with today became the standard.

So what’s that oddball license plate you have hanging in your garage worth? It depends. Condition is important as well as rarity. I looked at eBay to see what prices were like. You can get a lot of interesting Idaho plates for less than $50. Someone was asking $500 for a particularly special one. You’ll want to collect them because you find it an interesting hobby, not because you have kids to put through college.

Thanks to Dan Smith for his years of knowledge that went into his Idaho License Plates book, and for the photo. Message me if you want to know how to get a copy. Your local bookstore probably doesn’t have one.

I’m a very minor collector of license plates. I have about 40 or 50, mostly because I keep my personalized plates when it’s time to replace them. And I’m old. There’s that.

Collectors lust for one of Idaho’s first state plates, issued in 1913. There are only a couple of those still around. Idaho issued only single plates for automobiles in 1913 and 1914, ensuring a little extra rarity. Other rarities are early city plates issued by Hailey, Nampa, Payette, Weiser, Lewiston, and Boise, prior to 1913. According to Dan Smith, an acknowledged expert on Idaho license plates, only 19 of those are known to exist.

Did you know there were once hand-painted Idaho license plates? From 1913 to 1924 dealer plates were embossed with the words IDAHO DEALER, but there were no embossed numbers. Dealers had numbers painted on them by professionals. For a time, if you lost your license plate you would be issued a “flat” plate with no number on it, and you were expected to have your number painted on it by a professional. There are only a handful of those around anymore.

The county designators on plates have been around since 1932, but they weren’t all the familiar letter/number combination we see today. In 1932, for instance, Ada county was A1, while Lewis County was K4. It wasn’t until 1945 that the system we’re familiar with today became the standard.

So what’s that oddball license plate you have hanging in your garage worth? It depends. Condition is important as well as rarity. I looked at eBay to see what prices were like. You can get a lot of interesting Idaho plates for less than $50. Someone was asking $500 for a particularly special one. You’ll want to collect them because you find it an interesting hobby, not because you have kids to put through college.

Thanks to Dan Smith for his years of knowledge that went into his Idaho License Plates book, and for the photo. Message me if you want to know how to get a copy. Your local bookstore probably doesn’t have one.

Published on November 20, 2018 04:00