Rick Just's Blog, page 216

November 18, 2018

How a Reservoir Became a Lake

Sometimes place names are a little deceptive, and deliberately so.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

Published on November 18, 2018 04:00

November 17, 2018

Wanigan

In Idaho, when you talk about a wanigan (or wannigan), you really should distinguish whether you mean a little one, or a really, really big one.

Traditionally, a wanigan is a dry box for a canoe. You could store all your gear in there, including food. If you have in mind building a canoe, you might want to start with the wanigan so you’ll get a little practice working with wood.

Or, if you are very dedicated to working with wood as a career, you might have a much larger wanigan in mind. During the heyday of log drives, especially in Northern Idaho, a wanigan was a house-size shelter on a raft that followed the log drive down a river. The kitchen and dining area for the logging crew was located on the wanigan. Many even had sleeping quarters.

The word came from the Algonquian language and was first seen in print about 1848.

Wanigan on the Clearwater, courtesy of the Forest History Society.

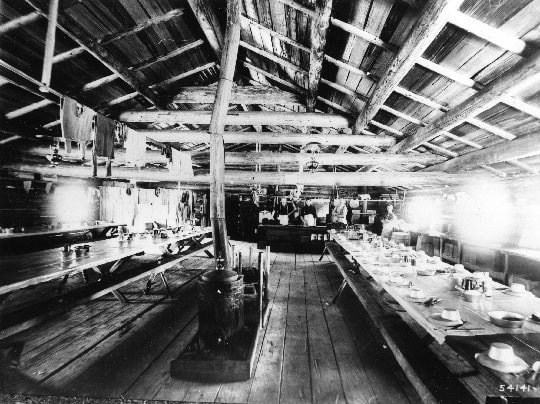

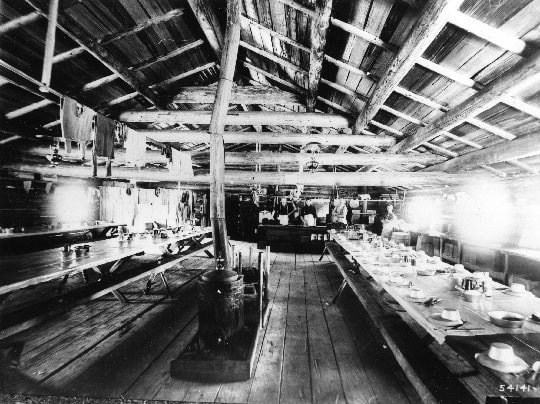

Wanigan on the Clearwater, courtesy of the Forest History Society.  Inside the cookhouse and dining hall of a wanigan, courtesy of the Clearwater Historical Society.

Inside the cookhouse and dining hall of a wanigan, courtesy of the Clearwater Historical Society.  Courtesy of the Forest History Society.

Courtesy of the Forest History Society.

Traditionally, a wanigan is a dry box for a canoe. You could store all your gear in there, including food. If you have in mind building a canoe, you might want to start with the wanigan so you’ll get a little practice working with wood.

Or, if you are very dedicated to working with wood as a career, you might have a much larger wanigan in mind. During the heyday of log drives, especially in Northern Idaho, a wanigan was a house-size shelter on a raft that followed the log drive down a river. The kitchen and dining area for the logging crew was located on the wanigan. Many even had sleeping quarters.

The word came from the Algonquian language and was first seen in print about 1848.

Wanigan on the Clearwater, courtesy of the Forest History Society.

Wanigan on the Clearwater, courtesy of the Forest History Society.  Inside the cookhouse and dining hall of a wanigan, courtesy of the Clearwater Historical Society.

Inside the cookhouse and dining hall of a wanigan, courtesy of the Clearwater Historical Society.  Courtesy of the Forest History Society.

Courtesy of the Forest History Society.

Published on November 17, 2018 04:00

November 16, 2018

Jesus Urquides

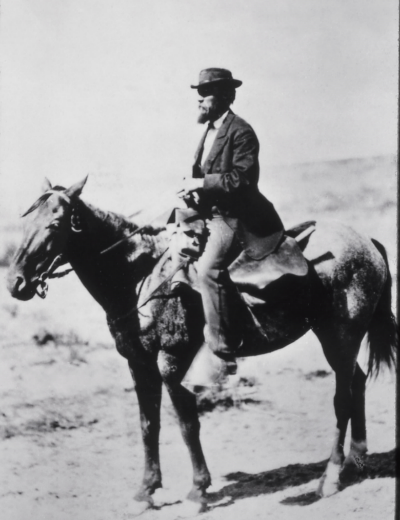

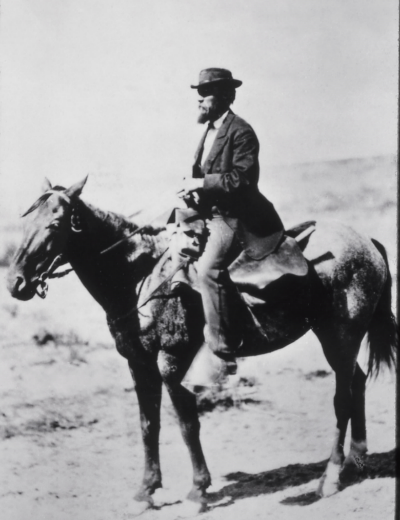

When you were a miner in the early days of Idaho, you couldn’t just order up supplies from Amazon. There were no planes, no trucks, and most importantly, no roads. Everything had to be packed in to remote areas, usually by a string of mules. If you had a big job, you counted on Jesus Urquides to get what you needed where you needed it.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

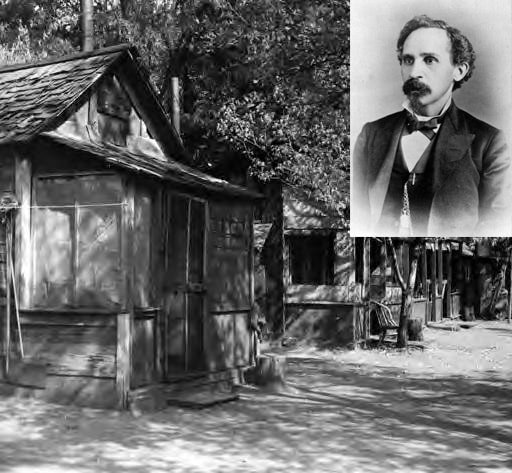

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on November 16, 2018 04:00

November 15, 2018

Spanish Charley

Part of the fun of chasing down stories for this blog is that I frequently get sidetracked. Angelo Aresco posted a picture (below) of a grave marker just over the border in Oregon in a comment on an earlier story. The marker for “Spanish Charley” was just enough to tease me. Here’s the story as told by the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman on April 5, 1887:

“Charles Albert, a well known cattleman in the Jordan Valley, and called ‘Spanish Charley,’ was shot dead last Wednesday by Jake Mussel, a sheep man.”

The paper explained that Albert had previously threatened to kill Jake Mussel because he was grazing sheep on what Albert considered his land. Mussel and his sheepherder went to Albert’s cabin to confront the man. The dialogue, according to the Statesman, went something like this:

“’Did you say you would kill me’ asked Mussel, as they approached.

‘Are you going to let your sheep run on my range?’ replied Charlie.

‘Yes,’ said Mussel, ‘I am going to let my sheep run on that range.’

‘Then I will kill you,’ said Charlie, and so saying he turned and rode toward his cabin, where it was known he kept one or two guns.

“When about halfway to the house, Mussel ordered him to stop, and on his refusal to do so, shot his horse from under him. Picking himself up Charlie continued on his way to the house, unmindful of Mussel, who again ordered him to stop. He had nearly reached the cabin when Mussel fired again, killing him instantly. Mussel then surrendered himself to the authorities in Baker City.”

Now, if that doesn’t sound like a perfectly pat argument for self-defense to you, you’re not alone. I found a couple of other versions of the story that sound more like Mussel was defending himself. In any case, he did not serve time for what the gravestone calls “Homocide.”

Charles Albert was never mentioned in the paper again, but Jacob Mussel got ink several times as a prominent rancher from Homedale and as the proprietor of Mussel Ferry. He happened to be the man who named Homedale. Residents there put suggested names for the town into a hat during a community picnic. When they pulled out the winner, the suggestion was the one put forward by Mussel. Why he wanted to name it that seems lost to history.

Charles Albert did get a little taste of immortality. There is a popular ATV/motorbike trail in Idaho and Oregon that today carries the name Spanish Charley.

“Charles Albert, a well known cattleman in the Jordan Valley, and called ‘Spanish Charley,’ was shot dead last Wednesday by Jake Mussel, a sheep man.”

The paper explained that Albert had previously threatened to kill Jake Mussel because he was grazing sheep on what Albert considered his land. Mussel and his sheepherder went to Albert’s cabin to confront the man. The dialogue, according to the Statesman, went something like this:

“’Did you say you would kill me’ asked Mussel, as they approached.

‘Are you going to let your sheep run on my range?’ replied Charlie.

‘Yes,’ said Mussel, ‘I am going to let my sheep run on that range.’

‘Then I will kill you,’ said Charlie, and so saying he turned and rode toward his cabin, where it was known he kept one or two guns.

“When about halfway to the house, Mussel ordered him to stop, and on his refusal to do so, shot his horse from under him. Picking himself up Charlie continued on his way to the house, unmindful of Mussel, who again ordered him to stop. He had nearly reached the cabin when Mussel fired again, killing him instantly. Mussel then surrendered himself to the authorities in Baker City.”

Now, if that doesn’t sound like a perfectly pat argument for self-defense to you, you’re not alone. I found a couple of other versions of the story that sound more like Mussel was defending himself. In any case, he did not serve time for what the gravestone calls “Homocide.”

Charles Albert was never mentioned in the paper again, but Jacob Mussel got ink several times as a prominent rancher from Homedale and as the proprietor of Mussel Ferry. He happened to be the man who named Homedale. Residents there put suggested names for the town into a hat during a community picnic. When they pulled out the winner, the suggestion was the one put forward by Mussel. Why he wanted to name it that seems lost to history.

Charles Albert did get a little taste of immortality. There is a popular ATV/motorbike trail in Idaho and Oregon that today carries the name Spanish Charley.

Published on November 15, 2018 04:00

November 14, 2018

Those Plastic Potato Pins

Brown plastic potato pins are ubiquitous in Idaho. Don't you have one? The Idaho Potato Commission will sell you a bag of 50 for $7. It was that commission, specifically its director Jay Sherlock, that came up with the idea for the pins.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

Published on November 14, 2018 04:00

November 13, 2018

Polly Bemis

I’ve seen the story of how Polly and Charlie Bemis became married called “romantic.” This is the kind of romance that people feel for ghost towns and gunslingers. Still, if you want to call winning a wife in a card game romantic, so be it.

That was the story told about Polly and Charlie Bemis for many years. There’s little evidence that such a high-stakes game ever took place, and Polly denied it in her final days.

There’s a lot about Polly’s life that is in some dispute. We know she was born on September 11, 1853 in Northern China. Her father is said to have sold her for two sacks of seed when she was a young woman. Her name was Lalu Nathoy. Unless it wasn’t. When she married Charlie her last name was written as Nathoy. Or, is that an H, making it Hathoy? Her first name has come down through the years as Lalu, but there doesn’t seem to be any written evidence that’s correct.

Polly, then. Polly Bemis. We’re not certain where and when or why Polly became Polly, but she used that name for most of her life in the United States.

She arrived in the US in 1872, smuggled into San Francisco. She had been purchased for $2500, probably as a concubine, by a Chinese man possibly named Hong King. He ran a saloon in Warren, Idaho Territory. It’s unclear how Polly disentangled herself from the man, but some scholars think he actually helped her gain her freedom.

Polly became friends with Charlie Bemis, who often served as her protector from drunken miners. Charlie had a saloon and gambling hall next to Hong King’s. Polly kept his room clean for him and provided other services, such as saving his life.

Charlie helped some of the miners by holding onto their pokes of gold dust while they caroused so that they didn’t drunkenly spend it all. One midnight one of those miners came to Charlie and demanded his poke. Charlie had agreed to hold the wealth against just such an inebriated request, so he refused. Later that night, the drunken miner crawled in Charlie’s window, woke the man up, and demanded his poke in a creative way. He lit a cigarette and promised that he’d shoot Charlie’s eye out when he finished it if Charlie didn’t give him the gold. Bemis drifted back to sleep so, cigarette smoked, the miner shot him in the face. He missed his eye, but the bullet entered Charlie’s cheek and lodged in the back of his neck.

Polly, who lived next door, heard the commotion and ran to Charlie’s room. A doctor was summoned. He examined the shooting victim and said Bemis was going to die. Polly didn’t give up on him, though. She took a razor to the back of his neck and dug the bullet out, then proceeded to nurse him back to health.

On August 14, 1894 Charlie and Polly were married. They moved from Warren to a site along the Salmon River some 17 miles north and filed a mining claim there. Charlie would live out life along the river. Polly would live most of hers there, too, though she moved back to Warren for a time after Charlie’s death in 1922 while neighbors rebuilt her cabin which had been lost by fire. In 1933 Polly became ill and was taken to Grangeville. She lived her last three months in the Idaho Valley Hospital there.

Polly is probably the best known Chinese woman in the history of the Pacific Northwest. Ruthanne Lum McCunn’s book Thousand Pieces of Gold probably tells her story best. It was turned into a movie of the same name that is a fictionalized version of Polly’s story.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

That was the story told about Polly and Charlie Bemis for many years. There’s little evidence that such a high-stakes game ever took place, and Polly denied it in her final days.

There’s a lot about Polly’s life that is in some dispute. We know she was born on September 11, 1853 in Northern China. Her father is said to have sold her for two sacks of seed when she was a young woman. Her name was Lalu Nathoy. Unless it wasn’t. When she married Charlie her last name was written as Nathoy. Or, is that an H, making it Hathoy? Her first name has come down through the years as Lalu, but there doesn’t seem to be any written evidence that’s correct.

Polly, then. Polly Bemis. We’re not certain where and when or why Polly became Polly, but she used that name for most of her life in the United States.

She arrived in the US in 1872, smuggled into San Francisco. She had been purchased for $2500, probably as a concubine, by a Chinese man possibly named Hong King. He ran a saloon in Warren, Idaho Territory. It’s unclear how Polly disentangled herself from the man, but some scholars think he actually helped her gain her freedom.

Polly became friends with Charlie Bemis, who often served as her protector from drunken miners. Charlie had a saloon and gambling hall next to Hong King’s. Polly kept his room clean for him and provided other services, such as saving his life.

Charlie helped some of the miners by holding onto their pokes of gold dust while they caroused so that they didn’t drunkenly spend it all. One midnight one of those miners came to Charlie and demanded his poke. Charlie had agreed to hold the wealth against just such an inebriated request, so he refused. Later that night, the drunken miner crawled in Charlie’s window, woke the man up, and demanded his poke in a creative way. He lit a cigarette and promised that he’d shoot Charlie’s eye out when he finished it if Charlie didn’t give him the gold. Bemis drifted back to sleep so, cigarette smoked, the miner shot him in the face. He missed his eye, but the bullet entered Charlie’s cheek and lodged in the back of his neck.

Polly, who lived next door, heard the commotion and ran to Charlie’s room. A doctor was summoned. He examined the shooting victim and said Bemis was going to die. Polly didn’t give up on him, though. She took a razor to the back of his neck and dug the bullet out, then proceeded to nurse him back to health.

On August 14, 1894 Charlie and Polly were married. They moved from Warren to a site along the Salmon River some 17 miles north and filed a mining claim there. Charlie would live out life along the river. Polly would live most of hers there, too, though she moved back to Warren for a time after Charlie’s death in 1922 while neighbors rebuilt her cabin which had been lost by fire. In 1933 Polly became ill and was taken to Grangeville. She lived her last three months in the Idaho Valley Hospital there.

Polly is probably the best known Chinese woman in the history of the Pacific Northwest. Ruthanne Lum McCunn’s book Thousand Pieces of Gold probably tells her story best. It was turned into a movie of the same name that is a fictionalized version of Polly’s story.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Published on November 13, 2018 04:00

November 12, 2018

Henrys Lake Ski Base

Idaho contributed to the war effort during World War II as the site of Farragut Naval Training Station, where more than 292,000 “boots” got their training. There was another training base proposed for Idaho about the same time. The Army even started construction on the site.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, and it is from his website where I obtained the information for this short piece. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

I urge you to read more about this on Tom’s site, and see the pictures of remaining foundations and other (pardon the pun) concrete evidence of the ill-fated base that can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, and it is from his website where I obtained the information for this short piece. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

I urge you to read more about this on Tom’s site, and see the pictures of remaining foundations and other (pardon the pun) concrete evidence of the ill-fated base that can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Published on November 12, 2018 11:00

November 11, 2018

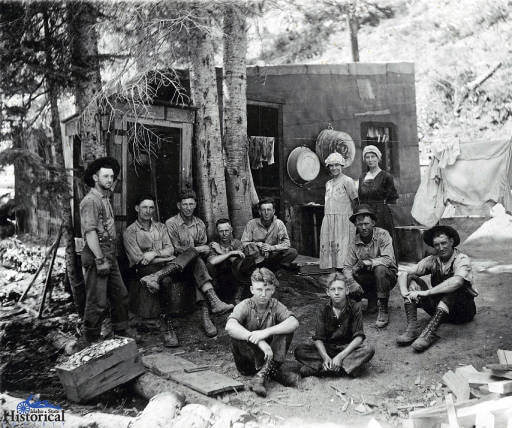

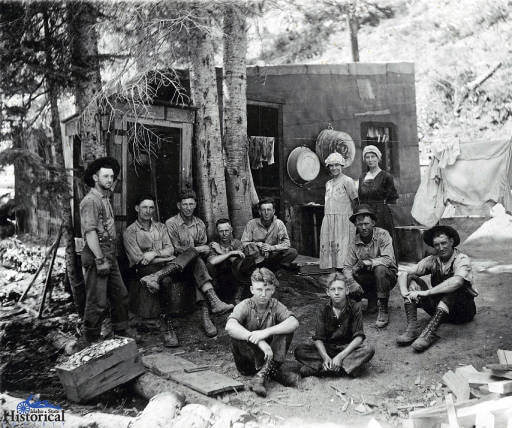

Gypo Loggers

Have you ever heard of a “gypo” logger? It’s a term used less today than it once was, because they are all but an endangered species. Gypo, or sometimes “gyppo,” loggers are those who work for themselves as opposed to loggers who work for a large logging company.

The term has its roots in the rough and tumble days of the labor movement. In 1917 the International Workers of the World (IWW), or Wobblies, called a strike to give loggers an eight-hour day in the Pacific Northwest. One theory about how gypo loggers got their name is that big logging companies tried to use Greek workers to break a strike in Everett, Washington. The term may have been a corruption of a Greek word meaning vulture. A more common theory is that it is a corruption of the word gypsy. In any case, the Wobblies began calling strikebreakers gypos, and the word became associated with independent contractors. It is said to be used almost exclusively in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

This photo of gypo loggers in camp was taken around 1918 somewhere in the Boise Basin. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

This photo of gypo loggers in camp was taken around 1918 somewhere in the Boise Basin. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

The term has its roots in the rough and tumble days of the labor movement. In 1917 the International Workers of the World (IWW), or Wobblies, called a strike to give loggers an eight-hour day in the Pacific Northwest. One theory about how gypo loggers got their name is that big logging companies tried to use Greek workers to break a strike in Everett, Washington. The term may have been a corruption of a Greek word meaning vulture. A more common theory is that it is a corruption of the word gypsy. In any case, the Wobblies began calling strikebreakers gypos, and the word became associated with independent contractors. It is said to be used almost exclusively in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

This photo of gypo loggers in camp was taken around 1918 somewhere in the Boise Basin. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

This photo of gypo loggers in camp was taken around 1918 somewhere in the Boise Basin. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on November 11, 2018 04:00

November 10, 2018

Hayden

A reader asked where the name Hayden came from for Hayden Creek in North Idaho. It seemed like a simple request, and I found the answer quickly in Lalia Boone’s definitive Idaho Place Names. Probably. Her explanation for the name Hayden Creek referred to a creek in Lemhi County, not the one that flows into Hayden Lake. That Hayden Creek flows from Hayden Basin. The basin and creek were named for Jim Hayden who was an early packer and freighter in the area. Hayden’s claim to fame was peppered with gunfire. Bill Smith, who was one of the first to discover gold in Leesburg, was playing cards with Jim Hayden in 1871. There was a dispute about a hand. Smith took umbrage at Hayden and fired at the man. Hayden was said to be unarmed, but he found a gun somewhere and shot back, killing Smith. Hayden was acquitted when he went to trial. His relief at that was short-lived. Hayden was killed by Indians in Birch Creek Valley in 1877.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boones book. The lake and town are named after Matt Heyden (sic), soit follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Heyden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Heyden won. Why the name is spelled differently is not explained in Boone’s book, but the U.S. Postal Service was frequently the culprit, having a reputation at that time for little attention to detail.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

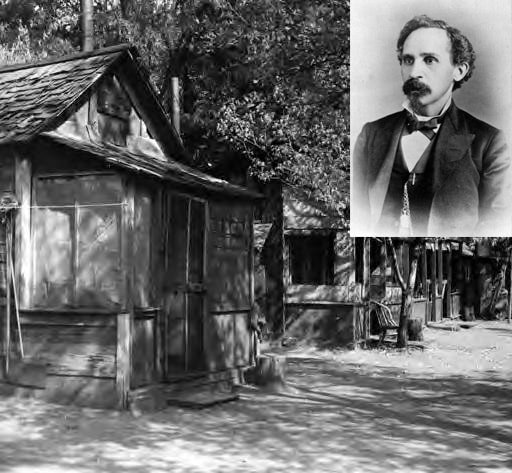

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader. This is a William Henry Jackson photo of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden.

This is a William Henry Jackson photo of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boones book. The lake and town are named after Matt Heyden (sic), soit follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Heyden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Heyden won. Why the name is spelled differently is not explained in Boone’s book, but the U.S. Postal Service was frequently the culprit, having a reputation at that time for little attention to detail.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

This is a William Henry Jackson photo of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden.

This is a William Henry Jackson photo of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden.

Published on November 10, 2018 04:00

November 9, 2018

Smylie Paints a Centennial Sign

Idaho has celebrated a couple of centennials. More people will remember the Idaho State Centennial that took place in 1990, but there was an earlier one celebrating Idaho’s Territorial Centennial in 1963.

To make sure visitors to the state were aware of the celebration, the Idaho Transportation Department painted a red “carpet” on the first 80 feet of inbound lanes on the major highways entering the state, with the message “Idaho Welcomes You” painted onto the red. On the outgoing lanes, 10-foot-high letters reading “Hurry Back” bid travelers adieu.

In the photo below, Idaho Governor Robert E. Smylie is giving the last touches of paint to one of 25 3’x5’ signs installed at the entry points for that year. He would do some more pretend painting on US 95 at the top of Lewiston Hill on the Idaho/Washington border May 3, 1963 to kick off the Territorial Centennial. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

To make sure visitors to the state were aware of the celebration, the Idaho Transportation Department painted a red “carpet” on the first 80 feet of inbound lanes on the major highways entering the state, with the message “Idaho Welcomes You” painted onto the red. On the outgoing lanes, 10-foot-high letters reading “Hurry Back” bid travelers adieu.

In the photo below, Idaho Governor Robert E. Smylie is giving the last touches of paint to one of 25 3’x5’ signs installed at the entry points for that year. He would do some more pretend painting on US 95 at the top of Lewiston Hill on the Idaho/Washington border May 3, 1963 to kick off the Territorial Centennial.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Published on November 09, 2018 04:00