Rick Just's Blog, page 213

December 19, 2018

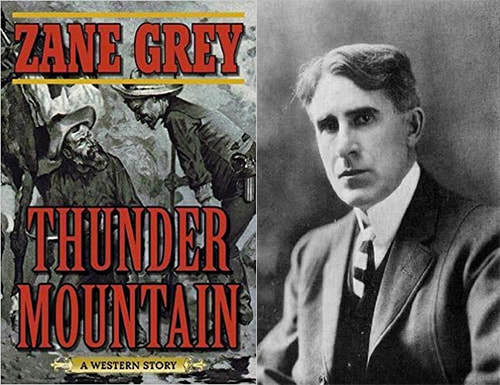

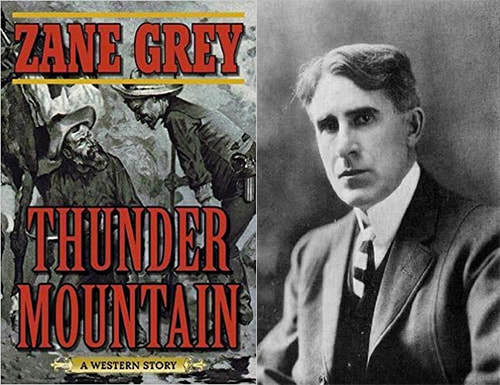

Zane Grey's Thunder Mountain

Zane Grey liked to get the setting for his books right. To that end, he made an extended visit to Idaho in the late 1920s with the idea of writing a book about the boomtown of Roosevelt and the Thunder Mountain mines.

Grey contacted well-know outfitter Elmer Keith and arranged to have him guide the writer into the backcountry. As Keith told it, in a 1957 article in the Idaho Statesman, Grey was not planning to rough it.

Said Keith, “I felt quite honored and looked forward to meeting this buckaroo.”

When Grey arrived, Keith began figuring out what it would take to get his gear into the mountains. It would require 42 pack horses and 12 riding horses. The portable bathtub proved a bit of a hurdle until Keith “finally bought an old mule blind in one eye, that did not object too much.”

Grey’s party included a private secretary and his own cook. In the beginning, the cook became an issue. He was variously reported to be French or Japanese (probably the latter). At any rate, it was foreign cooking and the packers did not like it one bit. They threatened to mutiny until the cook stated serving hotcakes, spuds, gravy, and meat. One of the packers later said “my esteem for Tagahashi grew every day. He was the best cook, the best packer, the best fisherman, and the best sport in the whole bunch.” That he always had plenty of coffee on hand for the cowboys was also of some consequence.

The party was delayed for a time when the Salmon Forest supervisor refused to let them pack in to Thunder Mountain because the drought had made the forest a tinderbox. “Zane Grey or no Zane Grey! Book or no book! The answer is still NO, Mr. Keith!” he is reported to have said.

Rains eventually came making the forest safe to travel. The group finally got to Thunder Mountain in a trip that took a total of six weeks, giving the author enough of a sense of the country to go home and write that book.

Thunder Mountain , by Zane Grey, was published in 1935 to good reviews and is still in print. The story features protagonists who were brothers discovering the first gold on the mountain, then defending their claim when word got out. Roosevelt, Idaho was called Thunder City in the book. Both the real town and its fictional doppelganger were destroyed when part of the mountain slid into the creek, backing up water to form a lake where the town once was.

The book was made into a movie, twice. The first was in 1935, starring George O’Brien who was a name actor at the time. “Gabby” Hayes was also in the film. The next version came out in 1947, starring Tim Holt. That version is still readily available.

Much of the information for this post came from the article “Zane Grey and Thunder Mountain,” by Robert G. Waite, published in the winter 1996 edition of Idaho Yesterdays.

Grey contacted well-know outfitter Elmer Keith and arranged to have him guide the writer into the backcountry. As Keith told it, in a 1957 article in the Idaho Statesman, Grey was not planning to rough it.

Said Keith, “I felt quite honored and looked forward to meeting this buckaroo.”

When Grey arrived, Keith began figuring out what it would take to get his gear into the mountains. It would require 42 pack horses and 12 riding horses. The portable bathtub proved a bit of a hurdle until Keith “finally bought an old mule blind in one eye, that did not object too much.”

Grey’s party included a private secretary and his own cook. In the beginning, the cook became an issue. He was variously reported to be French or Japanese (probably the latter). At any rate, it was foreign cooking and the packers did not like it one bit. They threatened to mutiny until the cook stated serving hotcakes, spuds, gravy, and meat. One of the packers later said “my esteem for Tagahashi grew every day. He was the best cook, the best packer, the best fisherman, and the best sport in the whole bunch.” That he always had plenty of coffee on hand for the cowboys was also of some consequence.

The party was delayed for a time when the Salmon Forest supervisor refused to let them pack in to Thunder Mountain because the drought had made the forest a tinderbox. “Zane Grey or no Zane Grey! Book or no book! The answer is still NO, Mr. Keith!” he is reported to have said.

Rains eventually came making the forest safe to travel. The group finally got to Thunder Mountain in a trip that took a total of six weeks, giving the author enough of a sense of the country to go home and write that book.

Thunder Mountain , by Zane Grey, was published in 1935 to good reviews and is still in print. The story features protagonists who were brothers discovering the first gold on the mountain, then defending their claim when word got out. Roosevelt, Idaho was called Thunder City in the book. Both the real town and its fictional doppelganger were destroyed when part of the mountain slid into the creek, backing up water to form a lake where the town once was.

The book was made into a movie, twice. The first was in 1935, starring George O’Brien who was a name actor at the time. “Gabby” Hayes was also in the film. The next version came out in 1947, starring Tim Holt. That version is still readily available.

Much of the information for this post came from the article “Zane Grey and Thunder Mountain,” by Robert G. Waite, published in the winter 1996 edition of Idaho Yesterdays.

Published on December 19, 2018 08:34

Fred Dubois and the Mormon Test Oath

In 1882, Fred T. Dubois might be found crawling beneath a house searching for a secret compartment where a polygamist was hiding. In 1887 he could be found in Congress, representing Idaho Territory. There was a solid link between the two activities.

Fred Dubois came to Idaho Territory in 1880 with his brother Dr. Jesse Dubois, Jr, who had been appointed physician at the Fort Hall Indian Agency. The younger Dubois—Fred was only 29—spent a few months as a cattle drive cowboy before he got into his preferred career, politics. The Dubois brothers grew up in Illinois. Their parents were friends with Abraham Lincoln. So, Fred Dubois had political connections in Washington, D.C. That smoothed the way for him to become U.S. Marshall for Idaho Territory, a position for which he had no discernable qualifications.

Nevertheless, he embraced the job, especially when it came to arresting Mormon polygamists. He was frustrated, though, because juries of their peers routinely set the polygamists free.

Dubois pushed to get a bill passed in the territorial legislature that would allow him to bring men with multiple wives to justice, even though polygamy was already illegal under federal law. The result was the “test oath.” Under the terms of the law territorial officials could require an oath of nonsupport of “celestial marriage” before a person could vote, hold office, or serve on a jury. Suddenly a jury of a polygamist’s peers could not include members of the LDS faith. The prohibition was soon ensconced in the Idaho constitution. It was enforced for only a few years, but remained in the constitution until 1982.

It wasn’t polygamy itself that Dubois abhorred, or the Mormon faith. It was the political power of Mormons he wanted to quell. They tended to vote in a block. In 1880, for instance, every vote in Bear Lake County was for a Democrat.

Politics was very much Fred T. Dubois’ game. He became popular with non-Mormons statewide, and since Mormons could no longer vote, he easily won election as a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. He was elected to the Senate after Idaho became a state, serving from 1901 to 1907.

Thanks to Randy Stapilus for his book Jerks in Idaho History , and Deana Lowe Jensen for her book about Fred T. Dubois, Let the Eagle Scream . I depended heavily on both for this post.

[image error]

Fred Dubois came to Idaho Territory in 1880 with his brother Dr. Jesse Dubois, Jr, who had been appointed physician at the Fort Hall Indian Agency. The younger Dubois—Fred was only 29—spent a few months as a cattle drive cowboy before he got into his preferred career, politics. The Dubois brothers grew up in Illinois. Their parents were friends with Abraham Lincoln. So, Fred Dubois had political connections in Washington, D.C. That smoothed the way for him to become U.S. Marshall for Idaho Territory, a position for which he had no discernable qualifications.

Nevertheless, he embraced the job, especially when it came to arresting Mormon polygamists. He was frustrated, though, because juries of their peers routinely set the polygamists free.

Dubois pushed to get a bill passed in the territorial legislature that would allow him to bring men with multiple wives to justice, even though polygamy was already illegal under federal law. The result was the “test oath.” Under the terms of the law territorial officials could require an oath of nonsupport of “celestial marriage” before a person could vote, hold office, or serve on a jury. Suddenly a jury of a polygamist’s peers could not include members of the LDS faith. The prohibition was soon ensconced in the Idaho constitution. It was enforced for only a few years, but remained in the constitution until 1982.

It wasn’t polygamy itself that Dubois abhorred, or the Mormon faith. It was the political power of Mormons he wanted to quell. They tended to vote in a block. In 1880, for instance, every vote in Bear Lake County was for a Democrat.

Politics was very much Fred T. Dubois’ game. He became popular with non-Mormons statewide, and since Mormons could no longer vote, he easily won election as a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. He was elected to the Senate after Idaho became a state, serving from 1901 to 1907.

Thanks to Randy Stapilus for his book Jerks in Idaho History , and Deana Lowe Jensen for her book about Fred T. Dubois, Let the Eagle Scream . I depended heavily on both for this post.

[image error]

Published on December 19, 2018 02:08

December 17, 2018

Who Invented Melon Gravel?

I’m writing a book about Farris Lind that should be out in the spring. In doing research, I was surprised to find out that the geological term “melon gravel” came about because of one of Lind’s Stinker Station signs. Perhaps his most famous sign, which was erected near Bliss. In a field of lava rocks tumbled and smoothed by the Bonneville Flood Gus Roos—Lind’s sign maker—planted a sign that said, “Petrified Watermelons—Take One Home To Your Mother-In-Law!” Roos painted a few rocks green to complete the effect.

People did stop and pick up rocks for souvenirs, some of them weighing a hundred pounds. Roos went back more than once to paint up more rocks.

One man who stopped to take a look at the rocks was named Harold E. Malde. He happened to be a geologist. He was so intrigued by the sign and the rocks and the idea of petrified watermelons, that he mentioned it in Geological Survey Professional Paper 596. The paper is about the impact of the Bonneville Flood. In it he said, “In 1955, amused by a whimsical billboard that advertised one patch of boulders as ‘petrified watermelons,’ we applied to them the descriptive geological name Mellon Gravel, which has since become one of the many evocative terms in stratigraphic nomenclature.” (Malde and Poweres, 1962, p. 1216)

Stay tuned. I’ll keep giving you updates and teasers about once a month until book comes out.

Thanks to Ed Harris for the use of the photo his dad Fred took of the watermelon sign many years ago. Fred took 40 pictures of the Stinker signs, most of which will be used in the upcoming book.

People did stop and pick up rocks for souvenirs, some of them weighing a hundred pounds. Roos went back more than once to paint up more rocks.

One man who stopped to take a look at the rocks was named Harold E. Malde. He happened to be a geologist. He was so intrigued by the sign and the rocks and the idea of petrified watermelons, that he mentioned it in Geological Survey Professional Paper 596. The paper is about the impact of the Bonneville Flood. In it he said, “In 1955, amused by a whimsical billboard that advertised one patch of boulders as ‘petrified watermelons,’ we applied to them the descriptive geological name Mellon Gravel, which has since become one of the many evocative terms in stratigraphic nomenclature.” (Malde and Poweres, 1962, p. 1216)

Stay tuned. I’ll keep giving you updates and teasers about once a month until book comes out.

Thanks to Ed Harris for the use of the photo his dad Fred took of the watermelon sign many years ago. Fred took 40 pictures of the Stinker signs, most of which will be used in the upcoming book.

Published on December 17, 2018 05:09

December 16, 2018

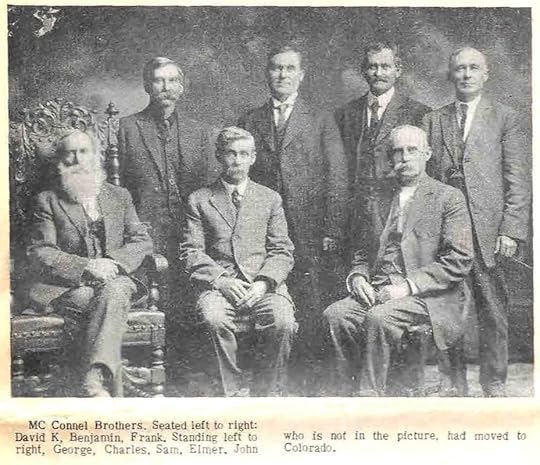

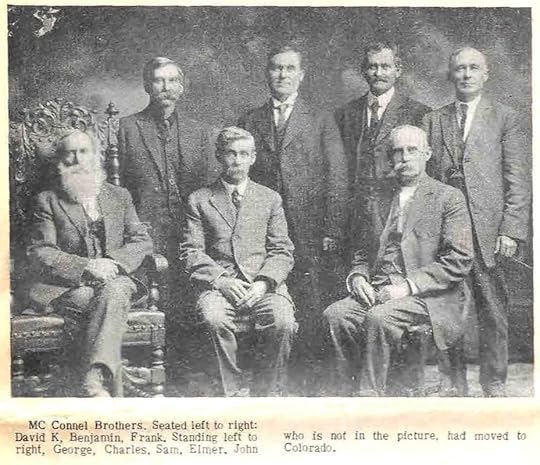

That Missing McConnel Island

If you do a Google search for McConnel Island, you’ll come up with a couple of near matches, one for the McConnel Islands, plural, near Antarctica, and one for McConnell Island (note the second L) in the San Jaun Islands in Washington State.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

Published on December 16, 2018 04:00

December 15, 2018

A Famous Painter in Idaho

In the 1860s, photography was new and publishers were still relying on illustrators for images to accompany articles. Thomas Moran, born in 1837 in Lancashire, England, had quite a reputation as an illustrator. He was the principal illustrator for Scribner’s, a leading publication in its day.

In 1871 the magazine asked Moran to illustrate articles on “The Wonders of Yellowstone” from the descriptions and amateur sketches of Nathaniel P. Langford. Langford was a politician in Territorial Montana who had the idea of publicizing the Yellowstone country in the interest of making it the first national park.

The Scribner’s illustrations led to an invitation from Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden for Moran to join his expedition to Yellowstone that year. The Northern Pacific Railroad had requested the invitation for Moran. They wanted him to produce a dozen paintings that might be used in future advertisements to entice people to Yellowstone, should the railroad extend a line there. They gave Moran $500 and a train ticket so that he could meet up with Hayden.

The expedition came through southeastern Idaho. Moran produced two watercolor sketches in Idaho while on the expedition, one of Portneuf Canyon and the other titled W. Springs C., which seems to have been painted near Lava Hot Springs. He also made a stop at my great grandparents’ home along the Blackfoot River, which I wrote about in an earlier post.

His Yellowstone paintings were instrumental in convincing Congress to create the country’s first national park in 1872. Congress purchased one of his paintings, The Grand Canon of the Yellowstone for $10,000. Hayden named one of the mountains in the Teton Range Mount Moran in honor of the artist, who had not yet seen it.

But those Idaho sketches weren’t the last Moran would create in Idaho. He returned to the state in 1879, making many sketches of the Teton Range from the Idaho side. According to the National Park Service, his painting The Great Teton Range, Idaho now hangs in the Oval Office in the White House, facing the president. It appeared in print for the first time in 1881 in Harpers Weekly.

Moran brought back some sketches of the Snake River, Taylor Bridge, and Fort Hall from his 1879 trip. In general he found little else to sketch that interested him.

But there was one more Idaho feature that brought him back to the state in 1900: Shoshone Falls. He had painted the falls a couple of times in earlier years from the sketches and photographs of others.

Moran and his daughter, Ruth, were guests of Ira B. Perrine whose ranch was in the canyon a few miles below the falls, and for whom Perrine bridge is named.

That his wife had recently died of typhoid fever might partially explain the foreboding darkness of what many consider his masterpiece. The enormous painting (below), six by eleven feet, features brooding clouds clinging close to the horizon. It is titled Shoshone falls on the Snake River, Idaho.

After Moran’s death in 1926, his daughter offered the painting to the State of Idaho for $15,000, then reduced the price to $10,000. The Legislature did not come up with the money and no philanthropist stepped forward. A shame, that.

Today the painting is owned by the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Much of the information for this post was taken from an article titled “Thomas Moran in Idaho, 1871-1900,” by Peter Boag, which appeared in the Fall 1998 Idaho Yesterdays magazine.

In 1871 the magazine asked Moran to illustrate articles on “The Wonders of Yellowstone” from the descriptions and amateur sketches of Nathaniel P. Langford. Langford was a politician in Territorial Montana who had the idea of publicizing the Yellowstone country in the interest of making it the first national park.

The Scribner’s illustrations led to an invitation from Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden for Moran to join his expedition to Yellowstone that year. The Northern Pacific Railroad had requested the invitation for Moran. They wanted him to produce a dozen paintings that might be used in future advertisements to entice people to Yellowstone, should the railroad extend a line there. They gave Moran $500 and a train ticket so that he could meet up with Hayden.

The expedition came through southeastern Idaho. Moran produced two watercolor sketches in Idaho while on the expedition, one of Portneuf Canyon and the other titled W. Springs C., which seems to have been painted near Lava Hot Springs. He also made a stop at my great grandparents’ home along the Blackfoot River, which I wrote about in an earlier post.

His Yellowstone paintings were instrumental in convincing Congress to create the country’s first national park in 1872. Congress purchased one of his paintings, The Grand Canon of the Yellowstone for $10,000. Hayden named one of the mountains in the Teton Range Mount Moran in honor of the artist, who had not yet seen it.

But those Idaho sketches weren’t the last Moran would create in Idaho. He returned to the state in 1879, making many sketches of the Teton Range from the Idaho side. According to the National Park Service, his painting The Great Teton Range, Idaho now hangs in the Oval Office in the White House, facing the president. It appeared in print for the first time in 1881 in Harpers Weekly.

Moran brought back some sketches of the Snake River, Taylor Bridge, and Fort Hall from his 1879 trip. In general he found little else to sketch that interested him.

But there was one more Idaho feature that brought him back to the state in 1900: Shoshone Falls. He had painted the falls a couple of times in earlier years from the sketches and photographs of others.

Moran and his daughter, Ruth, were guests of Ira B. Perrine whose ranch was in the canyon a few miles below the falls, and for whom Perrine bridge is named.

That his wife had recently died of typhoid fever might partially explain the foreboding darkness of what many consider his masterpiece. The enormous painting (below), six by eleven feet, features brooding clouds clinging close to the horizon. It is titled Shoshone falls on the Snake River, Idaho.

After Moran’s death in 1926, his daughter offered the painting to the State of Idaho for $15,000, then reduced the price to $10,000. The Legislature did not come up with the money and no philanthropist stepped forward. A shame, that.

Today the painting is owned by the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Much of the information for this post was taken from an article titled “Thomas Moran in Idaho, 1871-1900,” by Peter Boag, which appeared in the Fall 1998 Idaho Yesterdays magazine.

Published on December 15, 2018 04:00

December 14, 2018

That Twisting Road

The Lewiston Hill road is an engineering marvel. Today it’s a four-lane, divided highway that allows drivers to zip up and down the road at 65 mph, hardly noticing the hill at all, unless you’re driving a truck. That wasn’t the case in 1915.

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

Published on December 14, 2018 04:00

December 13, 2018

The Indispensable Lalia Boone

If there is one indispensable book for a researcher of Idaho history, I would nominate Lalia Boone’s

Idaho Place Names, a Geographical Dictionary

. Now the bad news. It’s out of print. You can pick one up occasionally in a bookstore that sells used books, and you can get one easily on Amazon through one of the many internet bookstores. Don’t expect it to be cheap, though.

Lalia spent more than 20 years pouring over old land patent records, tax filings, maps, mining claims, post office records, Lewis and Clark expedition notes, old hunting guides, and personal papers to get the answer to that enduring question, “How did that place get its name?” She also traveled all over the state interviewing old-timers.

The result was the definitive dictionary of Idaho place names. It lists the origin of hundreds of place names from creeks to cities. Inevitably, she missed a few because names come and go. Her book follows the name changes through the years as, for instance, Taylors Ferry, became Taylors Bridge, then Eagle Rock, and finally Idaho Falls.

Lalia Boone was born in 1907, in Tehuacana, Texas. She received her bachelor's in English from East Texas State College in 1938, and her master's in medieval literature and linguistics at the University of Oklahoma in 1947. In 1951 she became the first woman to receive a doctoral degree, in medieval literature and linguistics, at the University of Florida. She taught at the universities of Oklahoma and Florida before coming to the University of Idaho. In 1965 Boone accepted a position as professor of English at the University of Idaho. She was a past president of the American Name Society. Boone retired from teaching in 1973. She died at 83 in 1990.

Lalia spent more than 20 years pouring over old land patent records, tax filings, maps, mining claims, post office records, Lewis and Clark expedition notes, old hunting guides, and personal papers to get the answer to that enduring question, “How did that place get its name?” She also traveled all over the state interviewing old-timers.

The result was the definitive dictionary of Idaho place names. It lists the origin of hundreds of place names from creeks to cities. Inevitably, she missed a few because names come and go. Her book follows the name changes through the years as, for instance, Taylors Ferry, became Taylors Bridge, then Eagle Rock, and finally Idaho Falls.

Lalia Boone was born in 1907, in Tehuacana, Texas. She received her bachelor's in English from East Texas State College in 1938, and her master's in medieval literature and linguistics at the University of Oklahoma in 1947. In 1951 she became the first woman to receive a doctoral degree, in medieval literature and linguistics, at the University of Florida. She taught at the universities of Oklahoma and Florida before coming to the University of Idaho. In 1965 Boone accepted a position as professor of English at the University of Idaho. She was a past president of the American Name Society. Boone retired from teaching in 1973. She died at 83 in 1990.

Published on December 13, 2018 04:00

December 12, 2018

Georgie Oakes

I’d seen this picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection, many times over the years but missed one interesting detail until recently. It’s the steamboat Georgie Oakes docked at Mission Landing near the Cataldo Mission of the Sacred Heart. The picture was taken around 1891.

Mission Landing was as far up the Coeur d’Alene River as you could get with a big boat. Supplies for the mines were off-loaded here onto a narrow-gauge railway (just visible in the lower right) that took them to the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, Kellogg, Wallace, and Murray. Ore went the other direction, down the railway to the landing and by boat from there.

What I hadn’t noticed before, until I read the picture description furnished by the Idaho State Historical Society, was that the “dock” the Georgie Oakes is tied up to is the cannibalized hull of the steamer Coeur d’Alene, the boat it replaced on the river.

Today we have a romanticized view of those often-elegant looking boats that plied the waters of Lake Coeur d’Alene, and the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe rivers. In their day, they were working boats that held little charm for most people. None of the many steamers that worked the waters are around still today. No one bothered to save even one. Most burned accidentally, or were scuttled. One went down as the center point of the Fourth of July celebration in 1927. People looked on while the burning boat sank into the lake, sputtering and smoking until it was only a memory. That was the fate of the grand lady of the lakes, the Georgie Oakes.

Mission Landing was as far up the Coeur d’Alene River as you could get with a big boat. Supplies for the mines were off-loaded here onto a narrow-gauge railway (just visible in the lower right) that took them to the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, Kellogg, Wallace, and Murray. Ore went the other direction, down the railway to the landing and by boat from there.

What I hadn’t noticed before, until I read the picture description furnished by the Idaho State Historical Society, was that the “dock” the Georgie Oakes is tied up to is the cannibalized hull of the steamer Coeur d’Alene, the boat it replaced on the river.

Today we have a romanticized view of those often-elegant looking boats that plied the waters of Lake Coeur d’Alene, and the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe rivers. In their day, they were working boats that held little charm for most people. None of the many steamers that worked the waters are around still today. No one bothered to save even one. Most burned accidentally, or were scuttled. One went down as the center point of the Fourth of July celebration in 1927. People looked on while the burning boat sank into the lake, sputtering and smoking until it was only a memory. That was the fate of the grand lady of the lakes, the Georgie Oakes.

Published on December 12, 2018 04:00

December 11, 2018

A Little Aviation History

There were two things I knew about Ray Crowder the minute I saw this photo in the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical collection. One, he was a pilot. Two, he was an angler. The picture was intriguing, so I decided to find out more.

Most people go through their lives with a minimum of two mentions in a local paper. Crowder had closer to 2,000 in the Idaho Statesman. Given that there seemed to be a couple of Ray Crowders, let’s conservatively say 1,500.

He sold a few airplanes through the classifieds, applied for some building permits, participated in some clubs, won a photo contest, and had more than his fair share of parking tickets. And then there was the flying.

His life was devoted to flying, with plenty of fishing on the side. Crowder began flying when he was 15 and logged more than 20,000 hours in the air. He barnstormed for flying circuses, flew minerals out of the Idaho mines for the war effort, and flew numerous rescue flights. He was an instructor for several flying services at the Boise airport. Crowder taught the ladies to fly. In 1937 he was listed as the instructor for the newly formed Associated Women Pilots of Boise. In 1942, he married one of those women pilots, Doris Willy.

In 1938 Crowder was all over the Statesman. He took a photographer up to get a series of aerials of the growing city, which the paper featured several times. He was searching for a lost hunter and took the winners of a poster contest sponsored by the Jaycees for an airplane ride. Crowder volunteered for a life and death mission. His picture was in the paper for teaching more than 300 people to fly—so far. He flew to Salt Lake City where he was to pick up some anti-botulism serum for an Emmett woman who was gravely ill. Unfortunately, he was grounded twice by weather and the serum didn’t reach her on time.

Crowder was one of the leaders of the Civil Air Patrol and an instructor for the wartime Civilian Pilot Training Program. He was a partner in the Emmett Airport, and ran it for a few years.

He was a cool pilot. That’s best illustrated by a story I ran across in the March 26, 1947 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Crowder was trying to sell an airplane to Boisean Dean Mutch. He took the man up in the new aircraft, rising into the sky from the municipal airport when only seconds into the flight a spray of oil from the engine covered the windshield of the plane. Crowder wanted some room to maneuver, so he pushed the button to retract the landing gear, meaning to climb a bit and bring the airplane around for a landing.

The landing gear retracted, then fell back down halfway. Unable to see much of anything, Crowder asked Mutch to crank the landing gear up. Or down, for that matter, one way or another. Mutch hand cranked it, but it wouldn’t do anything but flop halfway open. Crowder gave the controls to Mutch and tried hand-cranking the gear himself. Same thing.

They were in touch with the control tower while they circled the airport waiting for a green light that would mean the landing gear was down. On each pass they saw nothing but a red light.

Crowder got tired of circling and decided it was time to bring the plane down. As if to add to their distractions as the plane started to get close to the ground an automatic horn in the cockpit began to blow relentlessly, warning them that the wheels weren’t down. It only stopped when Crowder killed all the switches to belly in on the grass.

When the men climbed out of the plane Crowder turned to Mutch and said, “I’m starved. Let’s go eat.” And, so they did.

Crowder, who passed away in 1986, is honored in the Idaho Aviation Hall of Fame.

Ray Crowder, fisherman and pilot.

Ray Crowder, fisherman and pilot.  The above clipping is from the October 12, 1940 Idaho Statesman.

The above clipping is from the October 12, 1940 Idaho Statesman.

Most people go through their lives with a minimum of two mentions in a local paper. Crowder had closer to 2,000 in the Idaho Statesman. Given that there seemed to be a couple of Ray Crowders, let’s conservatively say 1,500.

He sold a few airplanes through the classifieds, applied for some building permits, participated in some clubs, won a photo contest, and had more than his fair share of parking tickets. And then there was the flying.

His life was devoted to flying, with plenty of fishing on the side. Crowder began flying when he was 15 and logged more than 20,000 hours in the air. He barnstormed for flying circuses, flew minerals out of the Idaho mines for the war effort, and flew numerous rescue flights. He was an instructor for several flying services at the Boise airport. Crowder taught the ladies to fly. In 1937 he was listed as the instructor for the newly formed Associated Women Pilots of Boise. In 1942, he married one of those women pilots, Doris Willy.

In 1938 Crowder was all over the Statesman. He took a photographer up to get a series of aerials of the growing city, which the paper featured several times. He was searching for a lost hunter and took the winners of a poster contest sponsored by the Jaycees for an airplane ride. Crowder volunteered for a life and death mission. His picture was in the paper for teaching more than 300 people to fly—so far. He flew to Salt Lake City where he was to pick up some anti-botulism serum for an Emmett woman who was gravely ill. Unfortunately, he was grounded twice by weather and the serum didn’t reach her on time.

Crowder was one of the leaders of the Civil Air Patrol and an instructor for the wartime Civilian Pilot Training Program. He was a partner in the Emmett Airport, and ran it for a few years.

He was a cool pilot. That’s best illustrated by a story I ran across in the March 26, 1947 edition of the Idaho Statesman. Crowder was trying to sell an airplane to Boisean Dean Mutch. He took the man up in the new aircraft, rising into the sky from the municipal airport when only seconds into the flight a spray of oil from the engine covered the windshield of the plane. Crowder wanted some room to maneuver, so he pushed the button to retract the landing gear, meaning to climb a bit and bring the airplane around for a landing.

The landing gear retracted, then fell back down halfway. Unable to see much of anything, Crowder asked Mutch to crank the landing gear up. Or down, for that matter, one way or another. Mutch hand cranked it, but it wouldn’t do anything but flop halfway open. Crowder gave the controls to Mutch and tried hand-cranking the gear himself. Same thing.

They were in touch with the control tower while they circled the airport waiting for a green light that would mean the landing gear was down. On each pass they saw nothing but a red light.

Crowder got tired of circling and decided it was time to bring the plane down. As if to add to their distractions as the plane started to get close to the ground an automatic horn in the cockpit began to blow relentlessly, warning them that the wheels weren’t down. It only stopped when Crowder killed all the switches to belly in on the grass.

When the men climbed out of the plane Crowder turned to Mutch and said, “I’m starved. Let’s go eat.” And, so they did.

Crowder, who passed away in 1986, is honored in the Idaho Aviation Hall of Fame.

Ray Crowder, fisherman and pilot.

Ray Crowder, fisherman and pilot.  The above clipping is from the October 12, 1940 Idaho Statesman.

The above clipping is from the October 12, 1940 Idaho Statesman.

Published on December 11, 2018 04:00

December 10, 2018

How did Discovery Park get its Name?

Published on December 10, 2018 04:00