Rick Just's Blog, page 214

December 9, 2018

Camp Wilder has been a lot of Things

Google “Camp Wilder” and you’re likely to come up with several links to the 1992-93 sitcom of the same name. It starred nobody you ever heard of and lasted only 19 episodes on ABC.

This is about a different Camp Wilder, the one near Wilder, Idaho. Wilder is just west of Caldwell, if you didn’t know.

Camp Wilder was a migratory labor camp during WWII. Unless you’re thinking of the Camp Wilder that was a POW camp for some of those years. Both provided labor for area farmers.

Camp Wilder started as a project of the Farm Security Administration, housing U.S. residents who were in need of work. As the war began pulling young men away from the fields, the U.S. started the Bracero program in 1942. Bracero means “manual laborer” in Spanish. The program invited laborers from Mexico north to work crops. Camp Wilder soon began focusing on this new labor force.

The Idaho Statesman reported in a short article in the December 19, 1945 issue that the Braceros had gone home for the year and that 213 of them had been housed at Camp Wilder that season.

The Bracero program continued in some form until 1964, nationally, but the program was halted in Idaho in 1947 when the Mexican Consul complained that the workers were being treated poorly.

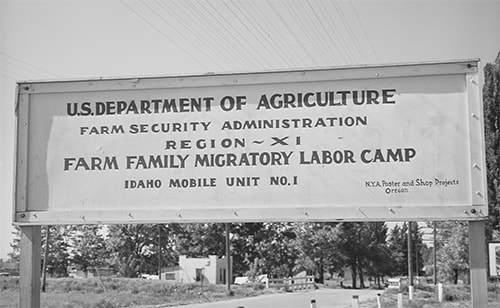

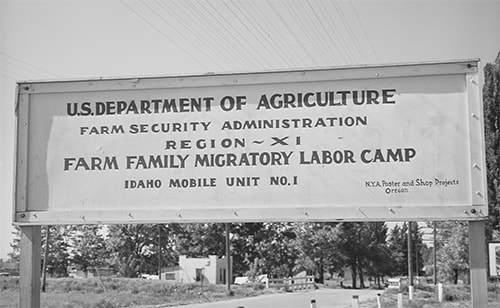

The photos below are courtesy of the Library of Congress and were taken at Camp Wilder circa 1941.

A young couple arrives at Camp Wilder looking for work.

A young couple arrives at Camp Wilder looking for work.  A sign at Camp Wilder.

A sign at Camp Wilder.  These tents housed the migratory workers at Camp Wilder.

These tents housed the migratory workers at Camp Wilder.  Health care was provided at the camp. Here a doctor and nurse make the rounds. I confess I included this one mostly because of the cool old bicycle in the photo.

Health care was provided at the camp. Here a doctor and nurse make the rounds. I confess I included this one mostly because of the cool old bicycle in the photo.

This is about a different Camp Wilder, the one near Wilder, Idaho. Wilder is just west of Caldwell, if you didn’t know.

Camp Wilder was a migratory labor camp during WWII. Unless you’re thinking of the Camp Wilder that was a POW camp for some of those years. Both provided labor for area farmers.

Camp Wilder started as a project of the Farm Security Administration, housing U.S. residents who were in need of work. As the war began pulling young men away from the fields, the U.S. started the Bracero program in 1942. Bracero means “manual laborer” in Spanish. The program invited laborers from Mexico north to work crops. Camp Wilder soon began focusing on this new labor force.

The Idaho Statesman reported in a short article in the December 19, 1945 issue that the Braceros had gone home for the year and that 213 of them had been housed at Camp Wilder that season.

The Bracero program continued in some form until 1964, nationally, but the program was halted in Idaho in 1947 when the Mexican Consul complained that the workers were being treated poorly.

The photos below are courtesy of the Library of Congress and were taken at Camp Wilder circa 1941.

A young couple arrives at Camp Wilder looking for work.

A young couple arrives at Camp Wilder looking for work.  A sign at Camp Wilder.

A sign at Camp Wilder.  These tents housed the migratory workers at Camp Wilder.

These tents housed the migratory workers at Camp Wilder.  Health care was provided at the camp. Here a doctor and nurse make the rounds. I confess I included this one mostly because of the cool old bicycle in the photo.

Health care was provided at the camp. Here a doctor and nurse make the rounds. I confess I included this one mostly because of the cool old bicycle in the photo.

Published on December 09, 2018 04:00

December 8, 2018

Military and Private Forts

Time for one of our occasional Now and Then features.

Today we’re seeing private business beginning to find ways of making money in space. First, NASA sent explorers into orbit and to the moon. Now, we have SpaceX, Boeing, and other business ventures following the path of government explorers. At some point in the future settlers might follow.

This was the same model of exploration used in the West. Lewis and Clark led the way with their Corps of Discovery from 1804 to 1806. Other government sponsored explorations followed, mostly in an effort to survey and describe the land. Businesses tried to make a buck in the new land not long after Lewis and Clark’s successful journey.

David Thompson established the first fur trading post in Idaho in 1809 for the Northwest Company. In 1813 John Reid established a post at the mouth of the Boise River where it enters the Snake. Reid’s venture died with him shortly after at the hands of the natives. Donald McKenzie, with Thompson’s North West Company, established a post on the same site in 1819. Indian opposition to same led to its quick abandonment.

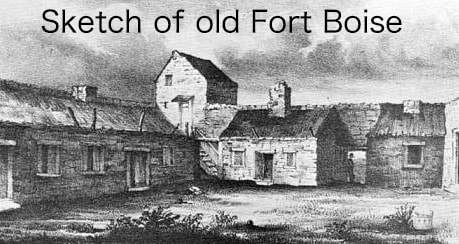

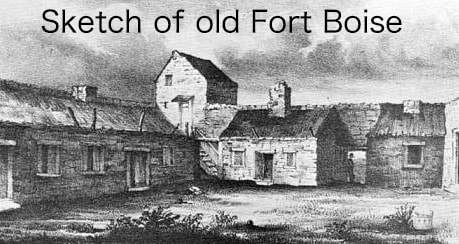

Thomas McKay, with the Hudson’s Bay Company picked the site again in 1834 for a post he called Fort Boise. It was in response to a new trading post built the same year near the Snake River about 280 miles to the east by Nathaniel Wyeth. Hudson’s Bay bought out Wyeth’s fort in 1837.

When settlers began making their way west, Fort Hall became an important supply point for Oregon Trail travelers. Fort Boise would serve the same function for many years. Francois Payette built a bigger, better Fort Boise for the Hudson’s Bay Company a few miles away in 1838. It operated until 1854 when flooding and continued Indian hostilities closed it.

The Fort Boise that helped kick-start the town of Boise was built by the military in 1863, about 40 miles east of the original fort.

Meanwhile, (condensing a lot of history) back at Fort Hall, things weren’t going that well for the Hudson’s Bay Company, either. The fort was abandoned in 1856. The military built a new Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1870, about 25 miles away from the Hudson’s Bay site.

Government involvement in exploration and forts was interwoven with the efforts of businesses and entrepreneurs (fur trappers) in the early days of the new frontier. Much the same is happening today with space exploration. You won’t be able to take your Conestoga wagon to Mars, or even your Tesla. Settlers are unlikely to encounter hostile natives on those first trips into the new frontier. Their challenges will be more basic: food, water, and breathable air.

Today we’re seeing private business beginning to find ways of making money in space. First, NASA sent explorers into orbit and to the moon. Now, we have SpaceX, Boeing, and other business ventures following the path of government explorers. At some point in the future settlers might follow.

This was the same model of exploration used in the West. Lewis and Clark led the way with their Corps of Discovery from 1804 to 1806. Other government sponsored explorations followed, mostly in an effort to survey and describe the land. Businesses tried to make a buck in the new land not long after Lewis and Clark’s successful journey.

David Thompson established the first fur trading post in Idaho in 1809 for the Northwest Company. In 1813 John Reid established a post at the mouth of the Boise River where it enters the Snake. Reid’s venture died with him shortly after at the hands of the natives. Donald McKenzie, with Thompson’s North West Company, established a post on the same site in 1819. Indian opposition to same led to its quick abandonment.

Thomas McKay, with the Hudson’s Bay Company picked the site again in 1834 for a post he called Fort Boise. It was in response to a new trading post built the same year near the Snake River about 280 miles to the east by Nathaniel Wyeth. Hudson’s Bay bought out Wyeth’s fort in 1837.

When settlers began making their way west, Fort Hall became an important supply point for Oregon Trail travelers. Fort Boise would serve the same function for many years. Francois Payette built a bigger, better Fort Boise for the Hudson’s Bay Company a few miles away in 1838. It operated until 1854 when flooding and continued Indian hostilities closed it.

The Fort Boise that helped kick-start the town of Boise was built by the military in 1863, about 40 miles east of the original fort.

Meanwhile, (condensing a lot of history) back at Fort Hall, things weren’t going that well for the Hudson’s Bay Company, either. The fort was abandoned in 1856. The military built a new Fort Hall on Lincoln Creek in 1870, about 25 miles away from the Hudson’s Bay site.

Government involvement in exploration and forts was interwoven with the efforts of businesses and entrepreneurs (fur trappers) in the early days of the new frontier. Much the same is happening today with space exploration. You won’t be able to take your Conestoga wagon to Mars, or even your Tesla. Settlers are unlikely to encounter hostile natives on those first trips into the new frontier. Their challenges will be more basic: food, water, and breathable air.

Published on December 08, 2018 04:00

December 7, 2018

Grandjean was a Legendary Forester

Born in Copenhagen in 1867, Emile Grandjean came to the United States when he was 17. Grandjean was from a privileged family. His father, Daniel Lublau Grandjean owned a landed estate and had the title of King’s Counselor. His uncle worked in the government’s forestry department and led young Emile in a study of forestry.

That early education did not seem to have amounted to anything when in 1883 Granjean set off for the United States to make a living from mining and trapping. He was in Nebraska for a short time before moving to the Wood River mining district in Idaho. In 1896 the gold of Alaska called. He spent three years searching for a strike, but ended up with little to show for it.

Grandjean moved back to Idaho and began mining near the headwaters of the Salmon River. He did well enough at that, but in 1906 he applied for a job as a ranger with the newly formed Forest Service. He took charge of the Sawtooth and Payette National Forests, then became the first supervisor of the Boise National Forest which was created from portions of the Sawtooth and Payette. His early training in forest management made him unusually qualified, since it was a new field in the U.S.

Grazers were not wild about the idea of the Forest Service telling them what to do, but Grandjean was a likable man who was able to eventually cool tempers. He was good at the often difficult job of representing the government, and stayed on as supervisor until 1922.

There is a valley, a creek, a mountain, and a campground named after Emile Grandjean.

There is also a living monument, in a sense. In 1912 Grandjean received some sequoia seedlings from John Muir. He planted two at his home in Boise. Two others were planted at the home of Fred and Alice Pittenger, both doctors. A later owner of the Grandjean home cut down the sequoias there, and only one survived at the Pittenger home. Eventually St. Lukes became the owner of that property and of the tree, which had become a Boise favorite. In June, 2017, the 98-foot-tall tree was moved across the street to make way for development at St. Lukes. It seems to be doing well in its new home near the Boise Little Theater.

Grandjean passed away in 1942 and is buried in the Canyon Hill Cemetery, Caldwell.

Emile Grandjean and his dog Granny, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Emile Grandjean and his dog Granny, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

That early education did not seem to have amounted to anything when in 1883 Granjean set off for the United States to make a living from mining and trapping. He was in Nebraska for a short time before moving to the Wood River mining district in Idaho. In 1896 the gold of Alaska called. He spent three years searching for a strike, but ended up with little to show for it.

Grandjean moved back to Idaho and began mining near the headwaters of the Salmon River. He did well enough at that, but in 1906 he applied for a job as a ranger with the newly formed Forest Service. He took charge of the Sawtooth and Payette National Forests, then became the first supervisor of the Boise National Forest which was created from portions of the Sawtooth and Payette. His early training in forest management made him unusually qualified, since it was a new field in the U.S.

Grazers were not wild about the idea of the Forest Service telling them what to do, but Grandjean was a likable man who was able to eventually cool tempers. He was good at the often difficult job of representing the government, and stayed on as supervisor until 1922.

There is a valley, a creek, a mountain, and a campground named after Emile Grandjean.

There is also a living monument, in a sense. In 1912 Grandjean received some sequoia seedlings from John Muir. He planted two at his home in Boise. Two others were planted at the home of Fred and Alice Pittenger, both doctors. A later owner of the Grandjean home cut down the sequoias there, and only one survived at the Pittenger home. Eventually St. Lukes became the owner of that property and of the tree, which had become a Boise favorite. In June, 2017, the 98-foot-tall tree was moved across the street to make way for development at St. Lukes. It seems to be doing well in its new home near the Boise Little Theater.

Grandjean passed away in 1942 and is buried in the Canyon Hill Cemetery, Caldwell.

Emile Grandjean and his dog Granny, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Emile Grandjean and his dog Granny, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photo collection.

Published on December 07, 2018 04:00

December 6, 2018

My own Private Idaho.

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel,

Keeping Private Idaho

. Today—forgive my indulgence—I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

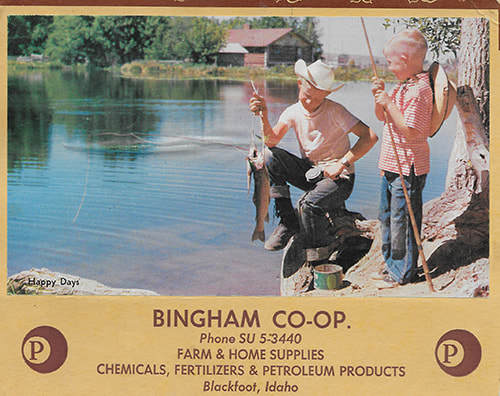

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

Published on December 06, 2018 04:00

December 5, 2018

Davis Levy's Lost Gold

Davis Levy was a Boise businessman in the 1880s and 90s whose businesses seemed to be on the seamy side, from a pawn shop to houses of ill repute. The man was liked little and when his life had a homicidal ending in 1901, the sobbing was much subdued.

I’ve already told that sordid story, and the link above will take you to it. Today’s story is about the aftermath of his murder.

Levy was a well-known miser. Stories of his having buried gold here and there were common. In August, 1902, a thief told law enforcement officers that he had found some of the Levy money buried somewhere when they took up the floorboards of a house and discovered gold coins. It turned out the thief had forged a signature on a stolen bond and cashed it.

Davis Levy was said to have once asked a group of workmen to lift up a part of the sidewalk around his place, and to their astonishment they uncovered a pot of his gold.

So it is not surprising that when the murdered man had little cash in his estate that people assumed he had buried some of it somewhere. The most popular “somewhere” of rumor was Cottonwood Gulch just outside the city. Levy had allegedly been observed leading a donkey laden with bags into Cottonwood Gulch, only to come back with empty bags. Speculation was that Levy was putting all his spare gold in a cave somewhere in the gulch, or burying it.

After his death gold hunters dug up acres of dirt in Cottonwood Gulch looking for Levy’s loot. A pair of treasure hunters had a better idea than just randomly digging. They got hold of Levy’s donkey and turned him loose at the mouth of the gulch, certain he would lead them to an oft-visited spot. The donkey took off with a purpose to the delight of the men. When they caught up with him, Levy’s donkey was happily munching away at a haystack.

No one ever came forward to say they had found the legendary gold of Davis Levy. But would they? Would they quietly spend it, instead? Or was there no gold to begin with? Levy did leave a sizable estate. Most of it was in property, not cash. So, we don’t know if there ever was a real rainbow’s end to this pot of gold story. Maybe nothing was ever hidden. We only know that Cottonwood Gulch, near old Fort Boise, is still there.

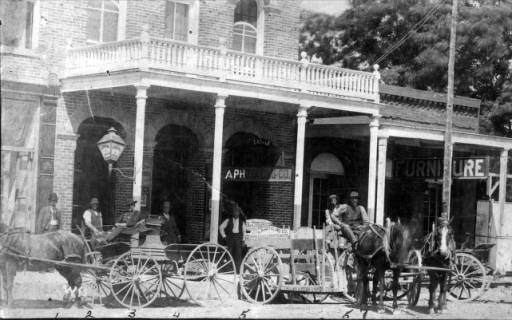

Levy’s boarding house. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Levy’s boarding house. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

I’ve already told that sordid story, and the link above will take you to it. Today’s story is about the aftermath of his murder.

Levy was a well-known miser. Stories of his having buried gold here and there were common. In August, 1902, a thief told law enforcement officers that he had found some of the Levy money buried somewhere when they took up the floorboards of a house and discovered gold coins. It turned out the thief had forged a signature on a stolen bond and cashed it.

Davis Levy was said to have once asked a group of workmen to lift up a part of the sidewalk around his place, and to their astonishment they uncovered a pot of his gold.

So it is not surprising that when the murdered man had little cash in his estate that people assumed he had buried some of it somewhere. The most popular “somewhere” of rumor was Cottonwood Gulch just outside the city. Levy had allegedly been observed leading a donkey laden with bags into Cottonwood Gulch, only to come back with empty bags. Speculation was that Levy was putting all his spare gold in a cave somewhere in the gulch, or burying it.

After his death gold hunters dug up acres of dirt in Cottonwood Gulch looking for Levy’s loot. A pair of treasure hunters had a better idea than just randomly digging. They got hold of Levy’s donkey and turned him loose at the mouth of the gulch, certain he would lead them to an oft-visited spot. The donkey took off with a purpose to the delight of the men. When they caught up with him, Levy’s donkey was happily munching away at a haystack.

No one ever came forward to say they had found the legendary gold of Davis Levy. But would they? Would they quietly spend it, instead? Or was there no gold to begin with? Levy did leave a sizable estate. Most of it was in property, not cash. So, we don’t know if there ever was a real rainbow’s end to this pot of gold story. Maybe nothing was ever hidden. We only know that Cottonwood Gulch, near old Fort Boise, is still there.

Levy’s boarding house. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Levy’s boarding house. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on December 05, 2018 04:00

December 4, 2018

Nope, not that Caribou

There are, occasionally, caribou in Idaho, and not just when Santa is flying over the state and, once again, pointedly skipping MY house. The caribou that wander in and out of Idaho in Boundary County, back and forth across the border with Canada, are the only caribou left in the Lower 48.

Note that the caribou are in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Note that the caribou are in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Published on December 04, 2018 04:00

December 3, 2018

"Gee, I’ll bet the Governor will be sore.”

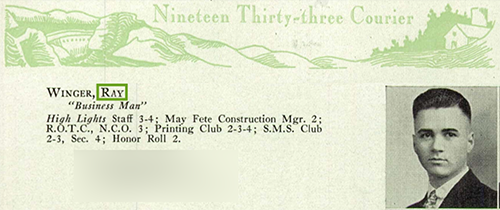

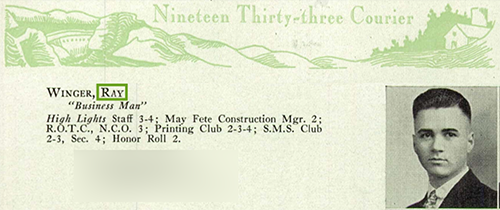

The 1933 Boise High School annual, the Courier, had an impressive list of accomplishments for senior Roy Winger. He was on the newspaper staff a couple of years, he was an ROTC NCO, he was in the Printing Club for three years, the SMS Club for two, and he was on the honor roll a couple of times. They called him a “Business Man.” He did so well in school that he completed his requirements for graduation in January, 1933, and was set to walk with his class in June.

It was probably the Printing Club where he went wrong. He developed an unhealthy interest in certain kinds of printed materials.

In January of 1933, when he was 18, Winger was arrested in Omaha when a check of the State of Idaho bond he was trying to pass showed that it had been stolen. Young Winger had lifted $230,000 worth of blank bonds from the Symms-York Printing Company. That would be $4.5 million in today’s dollars.

Blank bonds would by themselves be worthless, so Winger wrote letters to Governor C. Ben Ross. Secretary of State Fred E. Lukens, and State Treasurer George C. Barrett asking questions about state government in order to obtain their signatures on the replies. Once he had them, he practiced forging the signatures until he was satisfied that they would pass inspection.

But forgery wasn’t enough. Each bond needed to carry the state seal. Winger figured that out, too. In an AP story published February 13, 1933 in the Idaho Statesman, Winger related it this way:

“The legislature was meeting and I noticed that the stenographer in the secretary of state’s office remained at her work several nights each week until after 6 o’clock. The building was always open and just at the entrance there was a case with keys to all doors hanging in it.

“I took these keys, opened an office and called the stenographer on the telephone. I told her to go to another office and when she left I went into the secretary of state’s office. I got the seal and carried it into the cloak room of the secretary’s private office and while there sealed all the bonds.”

It took some ingenuity to pull that off, as well as some strength. The seal weighed about 100 pounds.

Once caught, Winger didn’t fight extradition to Boise. But he was quoted as saying, “What’s going to make it tough will be to have to face my mother and the officials whose names I forged on the bonds. Gee, I’ll bet the Governor will be sore.”

With Winger’s arrest, the story seemed to dwindle. I couldn’t find anything about a trial and failed to find any records for Winger in old penitentiary documents. Perhaps they went light on him because of his youth and sent him to St. Anthony correctional center instead of the prison.

But, we know he was convicted, because another shoe dropped in December of 1936. Winger was in the news again as the “former convict” arrested for theft of $4,000 worth of printing equipment from Caxton Press in Caldwell. He seemed to be preparing it for shipping. Ink, apparently, was in his blood.

Again, the trail goes cold. I could find no further mention of Winger in the Statesman or any other newspaper in the region. I do have a good source that indicates he married and had a son some years later. Winger died in 1992.

It’s frustrating not to be able to tie up all the loose ends. That’s not unusual when doing research. Even so, I thought the story of Winger’s audacious crime was worth retelling.

It was probably the Printing Club where he went wrong. He developed an unhealthy interest in certain kinds of printed materials.

In January of 1933, when he was 18, Winger was arrested in Omaha when a check of the State of Idaho bond he was trying to pass showed that it had been stolen. Young Winger had lifted $230,000 worth of blank bonds from the Symms-York Printing Company. That would be $4.5 million in today’s dollars.

Blank bonds would by themselves be worthless, so Winger wrote letters to Governor C. Ben Ross. Secretary of State Fred E. Lukens, and State Treasurer George C. Barrett asking questions about state government in order to obtain their signatures on the replies. Once he had them, he practiced forging the signatures until he was satisfied that they would pass inspection.

But forgery wasn’t enough. Each bond needed to carry the state seal. Winger figured that out, too. In an AP story published February 13, 1933 in the Idaho Statesman, Winger related it this way:

“The legislature was meeting and I noticed that the stenographer in the secretary of state’s office remained at her work several nights each week until after 6 o’clock. The building was always open and just at the entrance there was a case with keys to all doors hanging in it.

“I took these keys, opened an office and called the stenographer on the telephone. I told her to go to another office and when she left I went into the secretary of state’s office. I got the seal and carried it into the cloak room of the secretary’s private office and while there sealed all the bonds.”

It took some ingenuity to pull that off, as well as some strength. The seal weighed about 100 pounds.

Once caught, Winger didn’t fight extradition to Boise. But he was quoted as saying, “What’s going to make it tough will be to have to face my mother and the officials whose names I forged on the bonds. Gee, I’ll bet the Governor will be sore.”

With Winger’s arrest, the story seemed to dwindle. I couldn’t find anything about a trial and failed to find any records for Winger in old penitentiary documents. Perhaps they went light on him because of his youth and sent him to St. Anthony correctional center instead of the prison.

But, we know he was convicted, because another shoe dropped in December of 1936. Winger was in the news again as the “former convict” arrested for theft of $4,000 worth of printing equipment from Caxton Press in Caldwell. He seemed to be preparing it for shipping. Ink, apparently, was in his blood.

Again, the trail goes cold. I could find no further mention of Winger in the Statesman or any other newspaper in the region. I do have a good source that indicates he married and had a son some years later. Winger died in 1992.

It’s frustrating not to be able to tie up all the loose ends. That’s not unusual when doing research. Even so, I thought the story of Winger’s audacious crime was worth retelling.

Published on December 03, 2018 04:00

December 2, 2018

Keeping Your Gold Safe

In the 1860s it wasn’t wise to carry around a lot of money or gold in Idaho Territory. There was always someone ready to relieve you of it and, perhaps, your life if you hesitated to turn over your wealth.

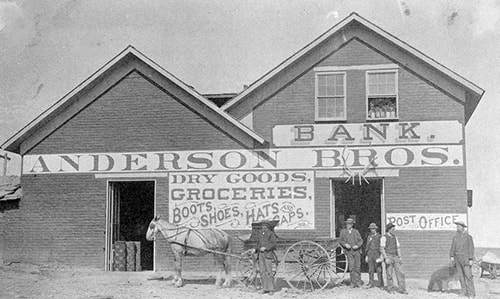

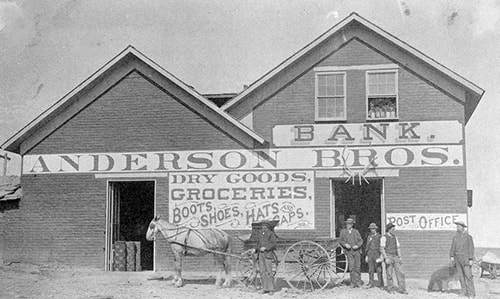

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Published on December 02, 2018 04:00

December 1, 2018

Idaho's Best-Known Historian

We’re doing something different today in honor of Idaho’s best-known historian, Merle Wells. I got to know Merle during the year and half I produced Idaho Snapshots, the official radio program of the Idaho Centennial. I won the contract for that daily radio program on the strength of my production skills and knowledge of radio. The Centennial Commission was less certain about my ability to tell stories that were historically accurate, so they asked Dr. Wells to review everything I wrote before I produced the programs.

I remember him as a knowledgeable, gentle mentor with a quiet sense of humor. But my memories would not do the man justice, so I asked Judy Austin, long-time friend and associate of Merle’s to do a short guest post. Judy herself was honored in 2015 with the Outstanding Achievement in the Humanities Award from the Idaho Humanities Council for her work as an Idaho historian, and as the long-time editor of Idaho Yesterdays.

Here is Judy’s remembrance:

Have you noticed the historical highway markers scattered across the state? The vast majority–well more than 200--were written by one man: Merle Wells, Idaho’s first state archivist, first state historian, first state historic preservation officer. December 1, 2018, is the hundredth anniversary of his birth.

Born in Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, to parents who were United States citizens, he came to Boise in 1930. He attended Boise Junior College and then The College of Idaho before going to the University of California, Berkeley, for his master’s in history. He planned to go on to law school; but Gene Chaffee, historian and president of BJC, convinced him to return to Berkeley for a Phd in history. Between work on the two degrees, he taught at C of I. And when he’d finished the PhD he taught for several years at Alliance College in Pennsylvania.

Each summer in those years, he returned to Boise. And in the summer of 1947, he made a remarkable discovery: official papers of Idaho’s governors, jammed into a closet in the state capitol. Thus began his work as an archivist—and the Idaho State Historical Society’s role as state archives. But only in 1959 did he become a full-time staff member at the society. Two years earlier, he became founding editor of the society’s journal, Idaho Yesterdays (no longer published).

Merle said that his greatest compliment was being called “the conscience of the historic preservation movement.” And that was probably his most wide-ranging contribution to the history of far more than just Idaho. As the national government’s historic preservation program got underway with federal funding in the 1970s, Merle did not hesitate to figure out ways to do things right even if the regulations didn’t quite agree—and, also without hesitation, to let the feds know if something wasn’t working properly or constructively (usually with recommendations on how to fix it to everyone’s benefit).

Through all these years, and until his death in 2000, he was a mentor to a vast number of younger historians, archivists, archaeologists, preservationists. He introduced us to Idaho’s history on the ground (and often on rough and unmarked roads), and he introduced us to Idaho’s people past and present. He wanted us to understand who and what had shaped the state over the decades—and at the time.

There was more to his life, professionally and otherwise. He wrote widely; he was active in groups of professional historians and archivists and was a co-founder of regional and Idaho conferences. And he saw each person, no matter background or training, as an equal. Among the results was his role in founding the Idaho Farm Workers Services and the Southern Idaho Migrant Ministry and his service on the National Council of Churches’ Migrant Ministry Committee. He served on the board of Zoo Boise. And, caring about history far beyond Idaho, he served on the board of the Presbyterian Historical Society.

No one has known and understood Idaho’s history better than Merle Wells; no one has cared more to share that knowledge and understanding with everyone.

I remember him as a knowledgeable, gentle mentor with a quiet sense of humor. But my memories would not do the man justice, so I asked Judy Austin, long-time friend and associate of Merle’s to do a short guest post. Judy herself was honored in 2015 with the Outstanding Achievement in the Humanities Award from the Idaho Humanities Council for her work as an Idaho historian, and as the long-time editor of Idaho Yesterdays.

Here is Judy’s remembrance:

Have you noticed the historical highway markers scattered across the state? The vast majority–well more than 200--were written by one man: Merle Wells, Idaho’s first state archivist, first state historian, first state historic preservation officer. December 1, 2018, is the hundredth anniversary of his birth.

Born in Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, to parents who were United States citizens, he came to Boise in 1930. He attended Boise Junior College and then The College of Idaho before going to the University of California, Berkeley, for his master’s in history. He planned to go on to law school; but Gene Chaffee, historian and president of BJC, convinced him to return to Berkeley for a Phd in history. Between work on the two degrees, he taught at C of I. And when he’d finished the PhD he taught for several years at Alliance College in Pennsylvania.

Each summer in those years, he returned to Boise. And in the summer of 1947, he made a remarkable discovery: official papers of Idaho’s governors, jammed into a closet in the state capitol. Thus began his work as an archivist—and the Idaho State Historical Society’s role as state archives. But only in 1959 did he become a full-time staff member at the society. Two years earlier, he became founding editor of the society’s journal, Idaho Yesterdays (no longer published).

Merle said that his greatest compliment was being called “the conscience of the historic preservation movement.” And that was probably his most wide-ranging contribution to the history of far more than just Idaho. As the national government’s historic preservation program got underway with federal funding in the 1970s, Merle did not hesitate to figure out ways to do things right even if the regulations didn’t quite agree—and, also without hesitation, to let the feds know if something wasn’t working properly or constructively (usually with recommendations on how to fix it to everyone’s benefit).

Through all these years, and until his death in 2000, he was a mentor to a vast number of younger historians, archivists, archaeologists, preservationists. He introduced us to Idaho’s history on the ground (and often on rough and unmarked roads), and he introduced us to Idaho’s people past and present. He wanted us to understand who and what had shaped the state over the decades—and at the time.

There was more to his life, professionally and otherwise. He wrote widely; he was active in groups of professional historians and archivists and was a co-founder of regional and Idaho conferences. And he saw each person, no matter background or training, as an equal. Among the results was his role in founding the Idaho Farm Workers Services and the Southern Idaho Migrant Ministry and his service on the National Council of Churches’ Migrant Ministry Committee. He served on the board of Zoo Boise. And, caring about history far beyond Idaho, he served on the board of the Presbyterian Historical Society.

No one has known and understood Idaho’s history better than Merle Wells; no one has cared more to share that knowledge and understanding with everyone.

Published on December 01, 2018 04:00

November 30, 2018

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). In what state is the town of Freedom located?

A. Utah

B. Montana

C. Wyoming

D. Idaho

E. Idaho and Wyoming

2). Why was Josiah Redwolf at the Lolo Pass dedication in 1957?

A. He designed the visitor center on the pass.

B. He had ridden across it with Chief Joseph in 1877.

C. He donated some of the land for the new highway.

D. He was one of the “Pony Express” riders that took part in the ceremony.

E. Trick question. He wasn’t there.

3). What two novels did B.M. Bower write while staying in Idaho?

A. The Good Indian

B. Ranch at the Wolverine

C. Letters of Long Ago

D. Lonesome Land

E. The Happy Family

4). Who killed “Spanish Charley”?

A. Charles Albert

B. Jake Mussel

C. Angelo Aresco

D. James Homedale

E. William J. McConnell

5) What’s a Wanigan?

A. An indigenous grinding stone.

B. The buffalo robe door often found on a tepee.

C. The Shoshone word for redux.

D. A floating cookhouse.

E. A leather bag mountain men carried necessary items in.

Answers

Answers

1, E

2, B

3, A & B

4, B

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). In what state is the town of Freedom located?

A. Utah

B. Montana

C. Wyoming

D. Idaho

E. Idaho and Wyoming

2). Why was Josiah Redwolf at the Lolo Pass dedication in 1957?

A. He designed the visitor center on the pass.

B. He had ridden across it with Chief Joseph in 1877.

C. He donated some of the land for the new highway.

D. He was one of the “Pony Express” riders that took part in the ceremony.

E. Trick question. He wasn’t there.

3). What two novels did B.M. Bower write while staying in Idaho?

A. The Good Indian

B. Ranch at the Wolverine

C. Letters of Long Ago

D. Lonesome Land

E. The Happy Family

4). Who killed “Spanish Charley”?

A. Charles Albert

B. Jake Mussel

C. Angelo Aresco

D. James Homedale

E. William J. McConnell

5) What’s a Wanigan?

A. An indigenous grinding stone.

B. The buffalo robe door often found on a tepee.

C. The Shoshone word for redux.

D. A floating cookhouse.

E. A leather bag mountain men carried necessary items in.

Answers

Answers1, E

2, B

3, A & B

4, B

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on November 30, 2018 04:00