Rick Just's Blog, page 210

January 19, 2019

Those Big Bones at Tolo Lake

Tolo Lake, near Grangeville, was in the news in the fall of 1994 when the Idaho Department of Fish and Game was deepening the drained lake to provide for better fishing. Fish and Game was hoping to take out a dozen feet of silt so that it could better support fish and waterfowl. What they found during the excavation was neither fish nor fowl. It was something much, much larger.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

#idahohistory #tololake #grangeville #mammoth

Tolo Lake

Tolo Lake

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

#idahohistory #tololake #grangeville #mammoth

Tolo Lake

Tolo Lake

Published on January 19, 2019 04:00

January 18, 2019

Which Came first, the Petrified Watermelon or the Melon Gravel?

I’m writing a book about Farris Lind that should be out in the spring. In doing research, I was surprised to find out that the geological term “melon gravel” came about because of one of Lind’s Stinker Station signs. Perhaps his most famous sign, which was erected near Bliss. In a field of lava rocks tumbled and smoothed by the Bonneville Flood Gus Roos—Lind’s sign maker—planted a sign that said, “Petrified Watermelons—Take One Home To Your Mother-In-Law!” Roos painted a few rocks green to complete the effect.

People did stop and pick up rocks for souvenirs, some of them weighing a hundred pounds. Roos went back more than once to paint up more rocks.

One man who stopped to take a look at the rocks was named Harold E. Malde. He happened to be a geologist. He was so intrigued by the sign and the rocks and the idea of petrified watermelons, that he mentioned it in Geological Survey Professional Paper 596. The paper is about the impact of the Bonneville Flood. In it he said, “In 1955, amused by a whimsical billboard that advertised one patch of boulders as ‘petrified watermelons,’ we applied to them the descriptive geological name Melon Gravel, which has since become one of the many evocative terms in stratigraphic nomenclature.” (Malde and Poweres, 1962, p. 1216)

Stay tuned. I’ll keep giving you updates and teasers about once a month until book comes out.

#idahohistory #fearlessfarris #farrislind #stinkerstations

People did stop and pick up rocks for souvenirs, some of them weighing a hundred pounds. Roos went back more than once to paint up more rocks.

One man who stopped to take a look at the rocks was named Harold E. Malde. He happened to be a geologist. He was so intrigued by the sign and the rocks and the idea of petrified watermelons, that he mentioned it in Geological Survey Professional Paper 596. The paper is about the impact of the Bonneville Flood. In it he said, “In 1955, amused by a whimsical billboard that advertised one patch of boulders as ‘petrified watermelons,’ we applied to them the descriptive geological name Melon Gravel, which has since become one of the many evocative terms in stratigraphic nomenclature.” (Malde and Poweres, 1962, p. 1216)

Stay tuned. I’ll keep giving you updates and teasers about once a month until book comes out.

#idahohistory #fearlessfarris #farrislind #stinkerstations

Published on January 18, 2019 04:00

January 17, 2019

A Deadly Explorer Preceded Lewis and Clark

The Corps of Discovery, also known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, travelled through a wilderness making new discoveries, naming plants and animals and mountains and rivers for the first time, and inspiring awe in the primitive people who barely subsisted there. Right?

Well, it was all new to them, but people had operated successful societies in that “unexplored” country for thousands of years. Those plants and animals and mountains and rivers already had names. The people who lived there were interested in the innovations the Corps of Discovery brought with them from pants with pockets to pistols and ammunition. But they probably thought the white men (and one black man) were woefully ignorant when they went hungry with food so easily attainable nearby.

Wilderness? The natives had no such concept. This was no unoccupied frontier. The Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota where the Corps spent the winter of 1804-1805 were more densely populated than St. Louis, according to an essay by Roberta Conner in the 2006 anthology Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes. The Expedition itself estimated there were 114 tribes living along or near their route.

What they did not report, because they did not know it, was that one newcomer from the Old World had preceded them, devastating the Indian population. According to Charles C. Mann in his book 1491, New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, smallpox took out as much as 90 percent of the native population in the Americas. Mark Trahant, a writer with Indian ancestry from Blackfoot, noted in the above-mentioned anthology that a smallpox epidemic swept through Shoshone country around 1780.

Lewis and Clark encountered a considerable civilization on their journey, though one much reduced from what it had been a few generations before.

If you would like to learn more about how the indigenous people of the Americas lived and the impact epidemic had on them, I recommend the books previously mentioned and Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond.

#idahohistory #smallpox #Robertaconner #marktrahant #corpsofdiscovery #lewisandclark Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Well, it was all new to them, but people had operated successful societies in that “unexplored” country for thousands of years. Those plants and animals and mountains and rivers already had names. The people who lived there were interested in the innovations the Corps of Discovery brought with them from pants with pockets to pistols and ammunition. But they probably thought the white men (and one black man) were woefully ignorant when they went hungry with food so easily attainable nearby.

Wilderness? The natives had no such concept. This was no unoccupied frontier. The Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota where the Corps spent the winter of 1804-1805 were more densely populated than St. Louis, according to an essay by Roberta Conner in the 2006 anthology Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes. The Expedition itself estimated there were 114 tribes living along or near their route.

What they did not report, because they did not know it, was that one newcomer from the Old World had preceded them, devastating the Indian population. According to Charles C. Mann in his book 1491, New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, smallpox took out as much as 90 percent of the native population in the Americas. Mark Trahant, a writer with Indian ancestry from Blackfoot, noted in the above-mentioned anthology that a smallpox epidemic swept through Shoshone country around 1780.

Lewis and Clark encountered a considerable civilization on their journey, though one much reduced from what it had been a few generations before.

If you would like to learn more about how the indigenous people of the Americas lived and the impact epidemic had on them, I recommend the books previously mentioned and Guns, Germs, and Steel by Jared Diamond.

#idahohistory #smallpox #Robertaconner #marktrahant #corpsofdiscovery #lewisandclark

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Published on January 17, 2019 04:00

January 16, 2019

Is that Waldo?

Many readers will remember the story about “Jimmy the Stiff” that I posted a year ago. That story resulted in a successful Go Fund Me campaign to get James Hogan a cemetery marker.

Idaho Statesman reporter Katherine Jones covered that effort. She recently sent me this photo, sent to her by Roxann Howell Dehlin of Nampa. Ms. Dehlin saw a photo of Hogan that ran with the article, looking a bit out of place in his scruffy clothes, posing with elected officials. It reminded her of this picture her family has.

The souvenir photo, apparently made for Sen. Anthony Russell, is well done and goes to great lengths to identify him. Left nameless is the gentleman at the upper left of the picture, peeking slyly around the wall in what we might today call a photo bomb.

Practically everyone in the picture wears a hat—even the photo bomber—with the exception of two gentlemen relegated to the back row, perhaps for their error in haberdashery.

Mysteries—even the most insignificant ones—are fun. We know next to nothing about who this man was, though it is probably safe to say he was not an Idaho state senator in 1905. What’s your wild guess?

#idahohistory #boisehistory

Idaho Statesman reporter Katherine Jones covered that effort. She recently sent me this photo, sent to her by Roxann Howell Dehlin of Nampa. Ms. Dehlin saw a photo of Hogan that ran with the article, looking a bit out of place in his scruffy clothes, posing with elected officials. It reminded her of this picture her family has.

The souvenir photo, apparently made for Sen. Anthony Russell, is well done and goes to great lengths to identify him. Left nameless is the gentleman at the upper left of the picture, peeking slyly around the wall in what we might today call a photo bomb.

Practically everyone in the picture wears a hat—even the photo bomber—with the exception of two gentlemen relegated to the back row, perhaps for their error in haberdashery.

Mysteries—even the most insignificant ones—are fun. We know next to nothing about who this man was, though it is probably safe to say he was not an Idaho state senator in 1905. What’s your wild guess?

#idahohistory #boisehistory

Published on January 16, 2019 04:00

January 15, 2019

Oceanfront Property in Riggins

If you think history doesn’t change, you’re just not paying attention. We learn things all the time that change our interpretation of history. Geology, though, that’s something you can count on.

Well…

Geologists are learning all the time, too. As certifiable human beings, they occasionally make mistakes and frequently disagree with one another.

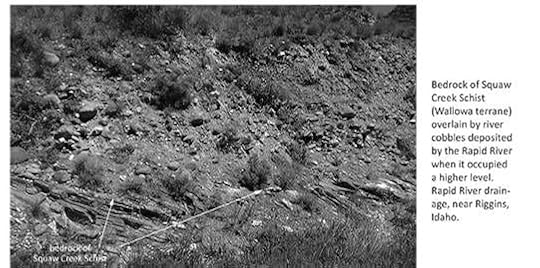

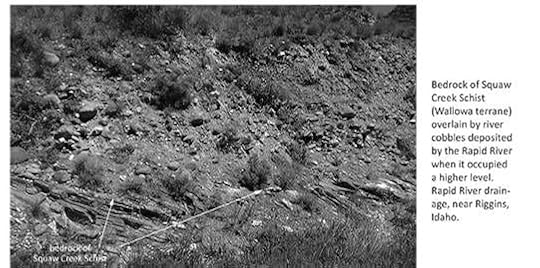

In my 1990 book, Idaho Snapshots, I joked about oceanfront property in Riggins, because at one time—not exactly last week—the area around Riggins would have overlooked the Pacific Ocean. This was a long time ago, in the Middle Permian to Early Cretaceous periods. I noted that what is now Washington and Oregon would have been an island before tectonic plate movement kissed that prehistorical land into what would become Idaho.

Lands roughly west of Riggins along a north-south squiggly line (not an official term of geology) from Alaska to Mexico did form at different times, play their roles as islands, then snuggle up against the North American continent, adding much beloved land to these United States, including California (see graphic).

Most of these islands were formed by volcanic activity or started as mountain ranges beneath the Pacific. They rode oceanic plates on their journey to their present position. The result is called accreted terrane, meaning that land masses formed somewhere else found a different home. Geologists generally agree that a wide swath of the west coast is accreted terrane. They disagree on exactly when and how it all came together.

Evidence that those islands piled up against the rest of the continent is on display in the Riggins area. The photo below, generously contributed by Terry Maley from his book Idaho Geology, shows where two radically different kinds of rocks are squished side-by-side to form part of what we call Idaho.

#idahohistory #terrymaley #idahogeology

Well…

Geologists are learning all the time, too. As certifiable human beings, they occasionally make mistakes and frequently disagree with one another.

In my 1990 book, Idaho Snapshots, I joked about oceanfront property in Riggins, because at one time—not exactly last week—the area around Riggins would have overlooked the Pacific Ocean. This was a long time ago, in the Middle Permian to Early Cretaceous periods. I noted that what is now Washington and Oregon would have been an island before tectonic plate movement kissed that prehistorical land into what would become Idaho.

Lands roughly west of Riggins along a north-south squiggly line (not an official term of geology) from Alaska to Mexico did form at different times, play their roles as islands, then snuggle up against the North American continent, adding much beloved land to these United States, including California (see graphic).

Most of these islands were formed by volcanic activity or started as mountain ranges beneath the Pacific. They rode oceanic plates on their journey to their present position. The result is called accreted terrane, meaning that land masses formed somewhere else found a different home. Geologists generally agree that a wide swath of the west coast is accreted terrane. They disagree on exactly when and how it all came together.

Evidence that those islands piled up against the rest of the continent is on display in the Riggins area. The photo below, generously contributed by Terry Maley from his book Idaho Geology, shows where two radically different kinds of rocks are squished side-by-side to form part of what we call Idaho.

#idahohistory #terrymaley #idahogeology

Published on January 15, 2019 04:00

January 13, 2019

No, not that Camas Prairie

After you’ve topped White Bird Pass, look to your left as you enter the rolling farm country around Grangeville. If you’re there in the early spring you can see patches of blue sometimes so thick they look like rippling ponds. If you’re paying attention you might pull over and read the Idaho Historical Society marker that explains that swatch of color. Camas. The flowering root was a key part of the diet of the Nez Perce.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

#idahohistory #camas #camasprairie

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

#idahohistory #camas #camasprairie

Published on January 13, 2019 04:00

January 12, 2019

Long Before Selfies, Boise Posed for Pictures

Anytime a new technology comes along, its use for illicit purposes follows closely behind. That was true with photography. The first mention of a photographer in the Idaho Statesman was a two-line story from San Francisco that told of someone being charged with the manufacture of indecent pictures. That was in 1865 when those naughty shots would have been daguerreotypes.

By 1867 the news was about a portrait photographer who had set up shop in town. Junk and Company Photographers, operated by John Junk, were offering their services in Boise’s classifieds for a couple of years. You could get “pictures in every style” as well as enameled cards. In 1869, Photographer Junk was mentioned in the Statesman once more, this time as a resident of Helena, Montana, and the victim of a fire, the fourth time flames had destroyed his business.

S.W. Wood was in town in the fall of 1873 with his camera and a tent set up on Eighth Street near the old court house where he was “prepared to do all kinds of work in his line, and at reasonable prices.” He was likely one of many traveling photographers of the day.

Boise had its own resident picture-taker again in 1874 when I.B. Curry set up shop. He operated until about 1880.

Photography was becoming a necessity among a certain class when in 1877 the Statesman carried this advice headlined “How to Fix the Mouth.”

“As the season is approaching when the ladies will be looking their prettiest, and the clear strong sunlight will be conducive to the highest success of the art, the following suggestions from a distinguished photographer may prove of great value:

“When a lady, sitting for a picture, would compose her mouth to a bland and serene character, she should, just upon entering the room, say ‘Bosom,’ and keep the expression into which the mouth subsides until the desired effect in the camera is evident.”

The article went on to suggest that if a lady were to want “to assume a distinguished and somewhat noble bearing, not suggestive of sweetness, she should say ‘Brush,’ the result of which is infallible. If she wishes to make her mouth look small, she must say ‘Flip,’ but if the mouth be already too small and needs enlarging she must say ‘Cabbage.’”

Whether or not the instructions were intended to form a mouth where the tongue would rest firmly in the cheek is not entirely clear.

The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman covered a photo shoot of 500 students in the spring of 1887. The City School students from first grade through high school were rounded up by “Prof. Daniels,” who was the superintendent of the school district, and arranged “them in a group, the large girls and boys in the rear, and the very little folks in various pretty attitudes in the fore-ground.” According to the paper “Photographer Cook blush(ed) at finding himself the object of one thousand curious and sparkling eyes.”

It would be a treat to see that old photo and to check for goofy faces, protruding tongues, and rabbit ears from fingers. How early did that start, do you suppose?

#idahohistory #boisehistory This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

By 1867 the news was about a portrait photographer who had set up shop in town. Junk and Company Photographers, operated by John Junk, were offering their services in Boise’s classifieds for a couple of years. You could get “pictures in every style” as well as enameled cards. In 1869, Photographer Junk was mentioned in the Statesman once more, this time as a resident of Helena, Montana, and the victim of a fire, the fourth time flames had destroyed his business.

S.W. Wood was in town in the fall of 1873 with his camera and a tent set up on Eighth Street near the old court house where he was “prepared to do all kinds of work in his line, and at reasonable prices.” He was likely one of many traveling photographers of the day.

Boise had its own resident picture-taker again in 1874 when I.B. Curry set up shop. He operated until about 1880.

Photography was becoming a necessity among a certain class when in 1877 the Statesman carried this advice headlined “How to Fix the Mouth.”

“As the season is approaching when the ladies will be looking their prettiest, and the clear strong sunlight will be conducive to the highest success of the art, the following suggestions from a distinguished photographer may prove of great value:

“When a lady, sitting for a picture, would compose her mouth to a bland and serene character, she should, just upon entering the room, say ‘Bosom,’ and keep the expression into which the mouth subsides until the desired effect in the camera is evident.”

The article went on to suggest that if a lady were to want “to assume a distinguished and somewhat noble bearing, not suggestive of sweetness, she should say ‘Brush,’ the result of which is infallible. If she wishes to make her mouth look small, she must say ‘Flip,’ but if the mouth be already too small and needs enlarging she must say ‘Cabbage.’”

Whether or not the instructions were intended to form a mouth where the tongue would rest firmly in the cheek is not entirely clear.

The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman covered a photo shoot of 500 students in the spring of 1887. The City School students from first grade through high school were rounded up by “Prof. Daniels,” who was the superintendent of the school district, and arranged “them in a group, the large girls and boys in the rear, and the very little folks in various pretty attitudes in the fore-ground.” According to the paper “Photographer Cook blush(ed) at finding himself the object of one thousand curious and sparkling eyes.”

It would be a treat to see that old photo and to check for goofy faces, protruding tongues, and rabbit ears from fingers. How early did that start, do you suppose?

#idahohistory #boisehistory

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

This picture of elegant women enjoying wine was probably taken about 1889 in Boise. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on January 12, 2019 04:00

January 11, 2019

Looking for Lake Hazel

Since my posts on Chicken Dinner Road and Protest Road, I’ve received several requests to tell how other roads got their names. I can’t research them all right away, but one did catch my attention. It was about Lake Hazel Road that runs from Maple Grove Road in Boise to S. Robinson Road in Nampa. The request wasn’t about how the road got its name. They wondered where the heck the lake was?

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

#idahohistory #lakehazel #lakehazelroad #chickendinnerroad #protestroad

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

#idahohistory #lakehazel #lakehazelroad #chickendinnerroad #protestroad

Published on January 11, 2019 04:00

January 10, 2019

We're Gathered here Today...

Funerals are solemn occasions, often marked by the telling of stories about the deceased. In September of 1991, they held one in Wallace for a deceased stoplight.

Over the years untold thousands of people stopped in Wallace because of that stoplight. Once the coast-to-coast road was dotted with traffic lights, but they disappeared one by one as the highway became an interstate. At some point, the Wallace stoplight became the only one on I-90 between Seattle and Boston. It probably caused more than one tourist to look around at the quaint little town and decide to stop and grab a burger or take a mine tour. A new viaduct would make stopping unnecessary so some in Wallace were a little concerned about the impact on the tourist trade.

As many as 10,000 vehicles a day were funneled through Wallace as they followed the longest Interstate Highway—3,024 miles—across the United States. The new viaduct would take traffic into the air above the town. Rather than crawling through the heart of Wallace travelers would now just fly by.

Even with the potential loss of tourism Wallace residents were generally happy with the nearly mile-long viaduct that took traffic by the town. The original plans were to destroy much of downtown Wallace to make room for the divided highway. A couple of buildings were torn down and the iconic railroad depot was moved to make way for the freeway, but the bulk of the town was saved.

The reaction to the new bypass by the tourism community in Wallace was to get quirky. The burial of the stoplight, which included a horse-drawn hearse and marching bagpipe players, was part of that. It went back up a few days later to control local traffic but was eventually taken down and put on display in the mining museum, in a coffin complete with artificial flowers. The quirkiness continues with the popular Oasis Bordello Museum, and the manhole cover in the middle of town declaring the spot to be the center of universe.

Tourism remains a big deal in Wallace. You can ride a zip line, bike the Hiawatha Trail through the tunnels, take a silver mine tour, and hike the Pulaski Trail to learn about the Big Burn of 1910.

For a couple of years Coeur d’Alene challenged Wallace’s “only stoplight” claim. During construction of I-90 past Coeur d’Alene drivers were shunted down Sherman Avenue for a time where they would encounter another stoplight. Today, no light impedes the flow of traffic on I-90 in Idaho or anywhere else.

#idahohistory #wallaceidaho

The stoplight, shown here with pallbearers on the day of the funeral, rests in state today at the mining museum in Wallace. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital photo collection.

The stoplight, shown here with pallbearers on the day of the funeral, rests in state today at the mining museum in Wallace. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital photo collection.

Over the years untold thousands of people stopped in Wallace because of that stoplight. Once the coast-to-coast road was dotted with traffic lights, but they disappeared one by one as the highway became an interstate. At some point, the Wallace stoplight became the only one on I-90 between Seattle and Boston. It probably caused more than one tourist to look around at the quaint little town and decide to stop and grab a burger or take a mine tour. A new viaduct would make stopping unnecessary so some in Wallace were a little concerned about the impact on the tourist trade.

As many as 10,000 vehicles a day were funneled through Wallace as they followed the longest Interstate Highway—3,024 miles—across the United States. The new viaduct would take traffic into the air above the town. Rather than crawling through the heart of Wallace travelers would now just fly by.

Even with the potential loss of tourism Wallace residents were generally happy with the nearly mile-long viaduct that took traffic by the town. The original plans were to destroy much of downtown Wallace to make room for the divided highway. A couple of buildings were torn down and the iconic railroad depot was moved to make way for the freeway, but the bulk of the town was saved.

The reaction to the new bypass by the tourism community in Wallace was to get quirky. The burial of the stoplight, which included a horse-drawn hearse and marching bagpipe players, was part of that. It went back up a few days later to control local traffic but was eventually taken down and put on display in the mining museum, in a coffin complete with artificial flowers. The quirkiness continues with the popular Oasis Bordello Museum, and the manhole cover in the middle of town declaring the spot to be the center of universe.

Tourism remains a big deal in Wallace. You can ride a zip line, bike the Hiawatha Trail through the tunnels, take a silver mine tour, and hike the Pulaski Trail to learn about the Big Burn of 1910.

For a couple of years Coeur d’Alene challenged Wallace’s “only stoplight” claim. During construction of I-90 past Coeur d’Alene drivers were shunted down Sherman Avenue for a time where they would encounter another stoplight. Today, no light impedes the flow of traffic on I-90 in Idaho or anywhere else.

#idahohistory #wallaceidaho

The stoplight, shown here with pallbearers on the day of the funeral, rests in state today at the mining museum in Wallace. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital photo collection.

The stoplight, shown here with pallbearers on the day of the funeral, rests in state today at the mining museum in Wallace. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital photo collection.

Published on January 10, 2019 04:00

January 9, 2019

Not that Hemingway

That beep, beep, beep you hear is the sound of me backing into this story. It’s about Hemingway Butte, which today is an off-highway vehicle play area managed by the Boise District Bureau of Reclamation. It includes a popular trail system and steep hillsides where OHVs and motorbikes defy gravity for a few seconds courtesy of two-cycle engines.

Hemmingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

#idahohistory #hemmingwaybutte Hemingway Butte recreation area, courtesy of the BLM.

Hemingway Butte recreation area, courtesy of the BLM.

Hemmingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

#idahohistory #hemmingwaybutte

Hemingway Butte recreation area, courtesy of the BLM.

Hemingway Butte recreation area, courtesy of the BLM.

Published on January 09, 2019 04:00