Rick Just's Blog, page 207

February 18, 2019

Kullyspell House

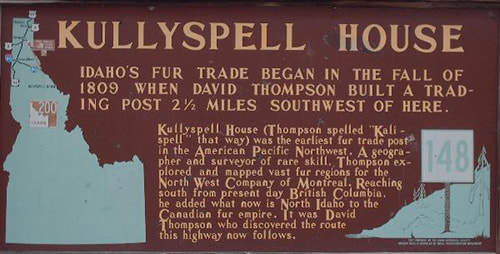

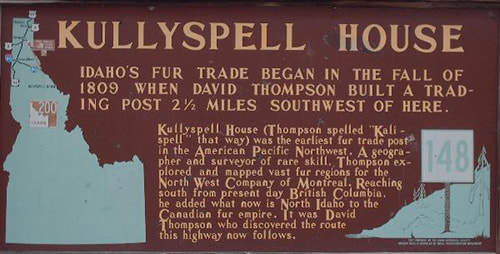

In 1809 explorer David Thompson, who worked for the North West Company, directed the construction of the first white establishment in what later became Idaho.

The trading post, called Kullyspell House, was located near present day Hope, about 16 miles from Sandpoint. The historical marker is on Idaho 200 at about mile marker 48.

It was made of split logs, and had two big stone chimneys. It was the chimneys that lasted the longest. For 87 years they stood like tombstones against the elements before finally toppling in a big windstorm. With the chimneys fallen, Kullyspell House all but vanished.

In time, even the locals forgot its exact location.

Then in 1928 a group of Idaho pioneers and historians set out to settle the question of just where Kullyspell House had been located. Ironically, they used a blind man as their guide. An aged Indian named Kali Too remembered seeing the chimneys as a child. Even though Kali Too had been blind for many years he remembered the landscape clearly. He told the group to go to a certain point along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille. From there, he told them to look for a big rock that was shaped like a bear's paw. Sure enough, when they got to the site there was a rock that looked like a bear's paw. From there the old Indian directed the party inland. In just a few minutes a cheer went up. They had found a pile of rocks that might once have been the missing chimneys. Later archaeological research proved it. Kullyspell House--or what was left of it--had been found. You might call it blind luck.

#davidthompson #kullyspellhouse

The trading post, called Kullyspell House, was located near present day Hope, about 16 miles from Sandpoint. The historical marker is on Idaho 200 at about mile marker 48.

It was made of split logs, and had two big stone chimneys. It was the chimneys that lasted the longest. For 87 years they stood like tombstones against the elements before finally toppling in a big windstorm. With the chimneys fallen, Kullyspell House all but vanished.

In time, even the locals forgot its exact location.

Then in 1928 a group of Idaho pioneers and historians set out to settle the question of just where Kullyspell House had been located. Ironically, they used a blind man as their guide. An aged Indian named Kali Too remembered seeing the chimneys as a child. Even though Kali Too had been blind for many years he remembered the landscape clearly. He told the group to go to a certain point along the shore of Lake Pend Oreille. From there, he told them to look for a big rock that was shaped like a bear's paw. Sure enough, when they got to the site there was a rock that looked like a bear's paw. From there the old Indian directed the party inland. In just a few minutes a cheer went up. They had found a pile of rocks that might once have been the missing chimneys. Later archaeological research proved it. Kullyspell House--or what was left of it--had been found. You might call it blind luck.

#davidthompson #kullyspellhouse

Published on February 18, 2019 04:00

February 17, 2019

That Special, Slippery, Slimy Fish

Would you like to do a little cod fishing in Idaho? You once could, and you didn’t need a deep sea fishing rig. Or, a sea, for that matter.

Burbot, or ling cod, are eel-like fish that hold the distinction of being the only freshwater member of the cod family. You won’t confuse them with any other fish. First, there’s that eel-like thing. Then there’s the rounded tail and single whisker, or barbel, sticking out from their lower jaw. Top that off with spots all over their body and you’ll know why they’re sometimes called “The Leopards of the Kootenai.”

The spawning habits of burbot are a little odd. They spawn in the dead of winter in shallow water with much thrashing about involved.

The fish have been important to the Kootenai Tribe for generations. When the Libby Dam went in, just across the border on the Kootenai River in Montana, the population of burbot dropped like a rock. That was in 1974. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game banned fishing for burbot in 1992. By 2004, Fish and Game biologists could capture only a dozen of the fish for research in a five-month period.

An effort to bring back the population, led by the Kootenai Tribe and Bonneville Power, proved successful. The Tribe invested $15 million in a hatchery for burbot and the equally threatened white sturgeon. Now there are an estimated 50,000 ling cod in the river, so for the first time in 27 years a fishing season has been set.

The fish are sometimes called “the poor man’s lobster” because of their slightly sweet taste.

#burbot #kootenaitribe #kootenairiver

Photos courtesy of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Photos courtesy of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Burbot, or ling cod, are eel-like fish that hold the distinction of being the only freshwater member of the cod family. You won’t confuse them with any other fish. First, there’s that eel-like thing. Then there’s the rounded tail and single whisker, or barbel, sticking out from their lower jaw. Top that off with spots all over their body and you’ll know why they’re sometimes called “The Leopards of the Kootenai.”

The spawning habits of burbot are a little odd. They spawn in the dead of winter in shallow water with much thrashing about involved.

The fish have been important to the Kootenai Tribe for generations. When the Libby Dam went in, just across the border on the Kootenai River in Montana, the population of burbot dropped like a rock. That was in 1974. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game banned fishing for burbot in 1992. By 2004, Fish and Game biologists could capture only a dozen of the fish for research in a five-month period.

An effort to bring back the population, led by the Kootenai Tribe and Bonneville Power, proved successful. The Tribe invested $15 million in a hatchery for burbot and the equally threatened white sturgeon. Now there are an estimated 50,000 ling cod in the river, so for the first time in 27 years a fishing season has been set.

The fish are sometimes called “the poor man’s lobster” because of their slightly sweet taste.

#burbot #kootenaitribe #kootenairiver

Photos courtesy of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Photos courtesy of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Published on February 17, 2019 04:00

February 16, 2019

Jackson Sundown

Did you ever play cowboys and Indians as a kid? Today’s story is about a man who wasn’t playing. He was a cowboy and an Indian.

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn was a nephew of Nez Perce Chief Joseph. He was 14 in 1877 when the flight of the Nez Perce took place across much of Idaho and parts of Oregon, Wyoming, and Montana. His uncle famously surrendered with the eloquent “I will fight no more forever” speech at Bear Paws Battlefield in Montana.

Meanwhile, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, wounded, went with a small group of Nez Perce into Canada where he lived for a couple of years with Sitting Bull’s Sioux.

He lived in Washington and Montana, gaining a reputation as a skilled horseman, and a new name, Jackson Sundown, before moving to Idaho in 1910. His skills atop a bucking bronco became so well-known that other riders would simply pull out of the competition when they heard Sundown had signed up. At least one rodeo manager solved that problem by paying Sundown $50 a day for exhibition bronc riding.

In 1911, Sundown along with George Fletcher, who was black, and John Spain, a white cowboy, competed at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in a famous multi-racial showdown. Ken Kesey told that story in his 1995 book, Last Go Round .

In 1915, at the age of 52, Jackson Sundown came in only third in bronc riding at the Pendleton Roundup. He decided to retire. But the next year, Alexander Phimister Proctor, a noted sculptor who was working on a sculpture of Sundown at the time talked the man into riding just once more. Jackson won the saddle bronc competition that day at the age of 53. Many of his competitors were half that age or less.

Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Culdesac, Idaho. He was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2006.

#kenkesey #jacksonsundown

The picture is of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver.

The picture is of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver.

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn was a nephew of Nez Perce Chief Joseph. He was 14 in 1877 when the flight of the Nez Perce took place across much of Idaho and parts of Oregon, Wyoming, and Montana. His uncle famously surrendered with the eloquent “I will fight no more forever” speech at Bear Paws Battlefield in Montana.

Meanwhile, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, wounded, went with a small group of Nez Perce into Canada where he lived for a couple of years with Sitting Bull’s Sioux.

He lived in Washington and Montana, gaining a reputation as a skilled horseman, and a new name, Jackson Sundown, before moving to Idaho in 1910. His skills atop a bucking bronco became so well-known that other riders would simply pull out of the competition when they heard Sundown had signed up. At least one rodeo manager solved that problem by paying Sundown $50 a day for exhibition bronc riding.

In 1911, Sundown along with George Fletcher, who was black, and John Spain, a white cowboy, competed at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in a famous multi-racial showdown. Ken Kesey told that story in his 1995 book, Last Go Round .

In 1915, at the age of 52, Jackson Sundown came in only third in bronc riding at the Pendleton Roundup. He decided to retire. But the next year, Alexander Phimister Proctor, a noted sculptor who was working on a sculpture of Sundown at the time talked the man into riding just once more. Jackson won the saddle bronc competition that day at the age of 53. Many of his competitors were half that age or less.

Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Culdesac, Idaho. He was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2006.

#kenkesey #jacksonsundown

The picture is of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver.

The picture is of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver.

Published on February 16, 2019 04:00

February 15, 2019

Lincoln's Idaho Connections

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

#idahostatehistoricalarchives #Lincoln #abrahamlincoln #idahohistory

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck Tuck.

#idahostatehistoricalarchives #Lincoln #abrahamlincoln #idahohistory

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

Published on February 15, 2019 04:00

February 14, 2019

Indian Rocks State Park

Several parks have come and gone over the 109-year history of state parks in Idaho. One you might remember is Indian Rocks State Park. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (technically the Idaho Department of Parks at the time) acquired 3,000 acres south of Pocatello from the US Bureau of Land Management in 1968 through the Federal Recreation and Public Purposes Act for $2.50 an acre. The Indian Rocks State Park visitor center was located on the west side of I-15 at the exit to Lava Hot Springs.

Park planners hoped campers would stop on their way to Yellowstone National Park. They also hoped a planned reservoir nearby would attract boaters and fishermen. The US Army Corps of Engineers decided there was not enough public support for building a reservoir on nearby Marsh Creek. The park closed in 1983 during a state budget crisis, and it never reopened.

#indianrocksstatepark #idahostateparkshistory

The visitor center at what was once Indian Rocks State Park.

The visitor center at what was once Indian Rocks State Park.

Park planners hoped campers would stop on their way to Yellowstone National Park. They also hoped a planned reservoir nearby would attract boaters and fishermen. The US Army Corps of Engineers decided there was not enough public support for building a reservoir on nearby Marsh Creek. The park closed in 1983 during a state budget crisis, and it never reopened.

#indianrocksstatepark #idahostateparkshistory

The visitor center at what was once Indian Rocks State Park.

The visitor center at what was once Indian Rocks State Park.

Published on February 14, 2019 04:00

February 13, 2019

Name that Dog

The most famous dog in Idaho history was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Meriwether Lewis paid $20 for him in August 1803. The Newfoundland was an uncommon breed at the time, but some of its characteristics were well known. A male typically weighs around 150 pounds. They are known as great swimmers, and built for it with a double coat to keep them warm and webbed feet. The dogs were favorites of sailors, which is probably why Lewis named his Seaman.

For decades people thought the dog’s name was Scannon, because making out Lewis’ handwriting was always a challenge. However, in 1984 a researcher discovered a clear reference to Seaman Creek, which was named after the dog.

Seaman proved his value to the Corps of Discovery early on. The men encountered what seemed to be a mass migration of squirrels on the Ohio River, September 11, 1803. Lewis commanded the dog to get a squirrel. He jumped right in, grabbed one, and brought it back. He kept jumping in and retrieving squirrels until they had enough for a meal. “They wer fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasant food,” Lewis wrote.

Later, while on the Mississippi, Lewis refused an offer for Seaman. He wrote, “One of the Shawnees a respectable looking Indian offered me three beverskins for my dog with which he appeared much pleased, the dog was of the newfoundland breed one that I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey and of course there was no bargan.”

The members of the Corps of Discovery soon learned to trust Seaman’s superior senses. He could tell when hunting parties were returning to camp or when a stranger was approaching. He got excited when he smelled bison. Seaman often accompanied Lewis on hunts, sometimes retrieving game he had shot.

Though Seaman was a skilled squirrel chaser he had no luck with prairie dogs. He loved to chase them but they always darted into burrow before his jaws could snap shut around them.

When the Corps of Discovery finally entered present day Idaho on August 12, 1805, Seaman was there. He was there, too, lying beside little “Pomp” on August 17 when Sacajawea was reunited with her brother. He was probably the only member of the party that was happy to see the snow fall in early September when they were short of food. The dog romped and played in it, insulated from any thought of cold by his thick coat.

As the men came closer to starvation, some may have eyed the dog as a possible source of food. No one would dare bring it up with Lewis, though the expedition did dine on some 200 dogs during their trek.

Meeting up with the Nez Perce later in the month solved the hunger problem. The canoes the expedition built on the Clearwater gave the dog a chance to skim across the water in the bow of one, or splash and play when they stopped to camp.

The dog was briefly stolen by Clatsop Indians when the expedition was working its way up the Columbia on the way back to home. They released Seaman when they saw they were being pursued.

Oddly, what ultimately happened to Seaman is a mystery. Newfoundlands live only eight or 10 years, but we have no record of when he died. The last mention of him in Lewis’ journal was on July 14, 1806 when he noted that mosquitos were terrible and that “My dog even howl’s with the torture he experiences from them.”

One clue seems to bolster the notion that he made it all the way back with the Corps of Discovery. A large dog collar on display in a Virginia museum has a plate on it with the inscription "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

#lewisandclark #corpsofdiscovery #seaman There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

For decades people thought the dog’s name was Scannon, because making out Lewis’ handwriting was always a challenge. However, in 1984 a researcher discovered a clear reference to Seaman Creek, which was named after the dog.

Seaman proved his value to the Corps of Discovery early on. The men encountered what seemed to be a mass migration of squirrels on the Ohio River, September 11, 1803. Lewis commanded the dog to get a squirrel. He jumped right in, grabbed one, and brought it back. He kept jumping in and retrieving squirrels until they had enough for a meal. “They wer fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasant food,” Lewis wrote.

Later, while on the Mississippi, Lewis refused an offer for Seaman. He wrote, “One of the Shawnees a respectable looking Indian offered me three beverskins for my dog with which he appeared much pleased, the dog was of the newfoundland breed one that I prised much for his docility and qualifications generally for my journey and of course there was no bargan.”

The members of the Corps of Discovery soon learned to trust Seaman’s superior senses. He could tell when hunting parties were returning to camp or when a stranger was approaching. He got excited when he smelled bison. Seaman often accompanied Lewis on hunts, sometimes retrieving game he had shot.

Though Seaman was a skilled squirrel chaser he had no luck with prairie dogs. He loved to chase them but they always darted into burrow before his jaws could snap shut around them.

When the Corps of Discovery finally entered present day Idaho on August 12, 1805, Seaman was there. He was there, too, lying beside little “Pomp” on August 17 when Sacajawea was reunited with her brother. He was probably the only member of the party that was happy to see the snow fall in early September when they were short of food. The dog romped and played in it, insulated from any thought of cold by his thick coat.

As the men came closer to starvation, some may have eyed the dog as a possible source of food. No one would dare bring it up with Lewis, though the expedition did dine on some 200 dogs during their trek.

Meeting up with the Nez Perce later in the month solved the hunger problem. The canoes the expedition built on the Clearwater gave the dog a chance to skim across the water in the bow of one, or splash and play when they stopped to camp.

The dog was briefly stolen by Clatsop Indians when the expedition was working its way up the Columbia on the way back to home. They released Seaman when they saw they were being pursued.

Oddly, what ultimately happened to Seaman is a mystery. Newfoundlands live only eight or 10 years, but we have no record of when he died. The last mention of him in Lewis’ journal was on July 14, 1806 when he noted that mosquitos were terrible and that “My dog even howl’s with the torture he experiences from them.”

One clue seems to bolster the notion that he made it all the way back with the Corps of Discovery. A large dog collar on display in a Virginia museum has a plate on it with the inscription "The greatest traveller of my species. My name is SEAMAN, the dog of captain Meriwether Lewis, whom I accompanied to the Pacific ocean through the interior of the continent of North America."

#lewisandclark #corpsofdiscovery #seaman

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

There are many statues of Seaman scattered around the United States. This one is at the Sacajawea Interpretive, Cultural, and Education Center in Salmon Idaho

Published on February 13, 2019 08:30

The Idaho Hotspot

What do you think of when you hear the term “Idaho hot spot?” Maybe a new restaurant or trendy bar? Not nearly as hot as the subject of today’s post.

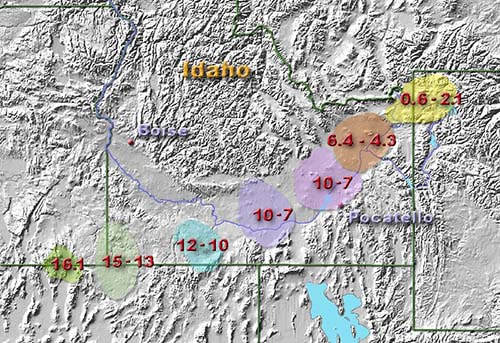

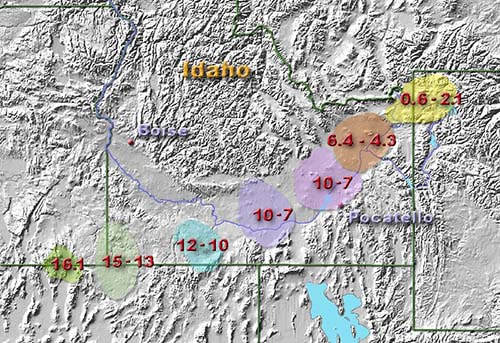

If you look at a topographic map of Idaho you can’t help but notice the swoop of the Snake River as it moves east to west through the southern part of the state. That’s called the Snake River Plain. It would be natural to assume that the Snake River created it, perhaps as it meandered back and forth through geologic time. That assumption would be wrong. The Snake River Plain was created by a lot of geological forces, including water erosion, but it’s primarily a signature left behind by a hot spot beneath the earth’s crust.

The crust of the earth is moving west in relation to this hot spot, so its impact is moving east. Think of the hot spot as being stationary while the crust moves west. In the illustration you can see where the hot spot was 16 million years ago along the Oregon/Nevada border. As the crust continued west, the stationary hot spot effectively move east. It “entered” the state some 15 million years ago, was somewhere around Bruneau Dunes about 12 million years ago, and was parked under Craters of the Moon National Monument about 7 to 10 million years ago.

As the hot spot moved, it produced a lot of volcanic activity on the surface. The Craters area is one visible indication of this. The area known as Island Park is where the hot spot made a big showing about 5 million years ago. It left behind a couple of calderas, or collapsed volcanoes. The Henry’s Fork Caldera is between 18 and 23 miles across. That’s huge. Still, it comfortably fits INSIDE the Island Park Caldera, which is 50 to 65 miles wide. Upper Mesa Falls is where the water of the Henrys Fork splashes over the edge of the old volcano.

So, has the hot spot gone away? Nope. You can find it today under Yellowstone National Park heating up the geysers and hot pools and causing social media to come unglued whenever there is swarm of earthquakes.

By the way, this is the same thing that’s going on with the Hawaiian Islands. That hot spot acts of as the earth’s crust moves over the top of it, too. Since there is no land mass the resulting volcanic activity produces islands. One of the oldest islands, Kauai, is to the furthest west. As that hot spot moved—in relation to the crust—east, it created Oahu, Maui, and then the Big Island, Hawaii. That’s where the volcanic activity is today.

#idahogeology #idahohotspot

The illustration is courtesy of Kelvin Case at English Wikipedia.

The illustration is courtesy of Kelvin Case at English Wikipedia.

If you look at a topographic map of Idaho you can’t help but notice the swoop of the Snake River as it moves east to west through the southern part of the state. That’s called the Snake River Plain. It would be natural to assume that the Snake River created it, perhaps as it meandered back and forth through geologic time. That assumption would be wrong. The Snake River Plain was created by a lot of geological forces, including water erosion, but it’s primarily a signature left behind by a hot spot beneath the earth’s crust.

The crust of the earth is moving west in relation to this hot spot, so its impact is moving east. Think of the hot spot as being stationary while the crust moves west. In the illustration you can see where the hot spot was 16 million years ago along the Oregon/Nevada border. As the crust continued west, the stationary hot spot effectively move east. It “entered” the state some 15 million years ago, was somewhere around Bruneau Dunes about 12 million years ago, and was parked under Craters of the Moon National Monument about 7 to 10 million years ago.

As the hot spot moved, it produced a lot of volcanic activity on the surface. The Craters area is one visible indication of this. The area known as Island Park is where the hot spot made a big showing about 5 million years ago. It left behind a couple of calderas, or collapsed volcanoes. The Henry’s Fork Caldera is between 18 and 23 miles across. That’s huge. Still, it comfortably fits INSIDE the Island Park Caldera, which is 50 to 65 miles wide. Upper Mesa Falls is where the water of the Henrys Fork splashes over the edge of the old volcano.

So, has the hot spot gone away? Nope. You can find it today under Yellowstone National Park heating up the geysers and hot pools and causing social media to come unglued whenever there is swarm of earthquakes.

By the way, this is the same thing that’s going on with the Hawaiian Islands. That hot spot acts of as the earth’s crust moves over the top of it, too. Since there is no land mass the resulting volcanic activity produces islands. One of the oldest islands, Kauai, is to the furthest west. As that hot spot moved—in relation to the crust—east, it created Oahu, Maui, and then the Big Island, Hawaii. That’s where the volcanic activity is today.

#idahogeology #idahohotspot

The illustration is courtesy of Kelvin Case at English Wikipedia.

The illustration is courtesy of Kelvin Case at English Wikipedia.

Published on February 13, 2019 02:18

February 12, 2019

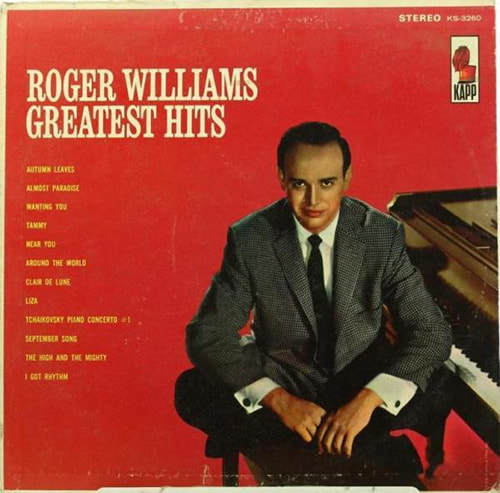

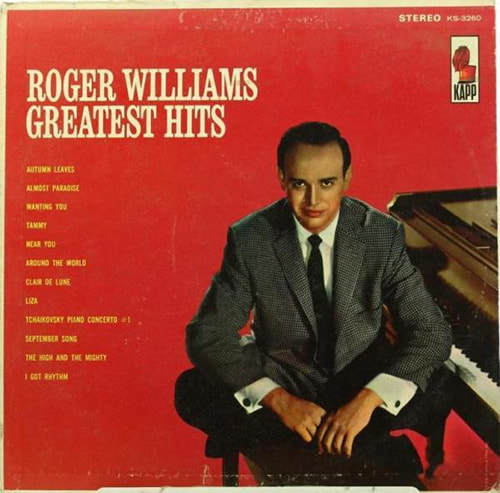

A Famous Pianist

Louis Jacob Weertz came to Idaho in 1943. He was one of almost 300,000 men who trained for World War II at Farragut Naval Training Station, where Farragut State Park is now. He played piano well even then, but at Farragut, he was probably best known for his boxing. Weertz was the welterweight champion boxer on the base.

Weertz was one of a handful of Farragut recruits who received part of their training at what was then the University of Idaho Southern Branch in Pocatello. He must have liked the city, because he came back after the war to attend college. He received a BA in music from ISU, then went on to get a Master's from Drake University. He studied further at Julliard in New York.

For whatever reason, Weertz decided to change his name while living in Pocatello. He allegedly pulled out a telephone book and ran his finger down the columns until he found one he liked. That name was Roger Williams.

There was only one Roger Williams in the phonebook at that time, according to the Roger Williams I knew. My friend, Roger, was a long-time Fish and Game employee and gained some measure of fame, along with Syd Tate, by charting out Idaho’s Centennial Trail.

The faux or, perhaps better-said, newly named Roger Williams gained quite a bit of fame in his time.

First, he won "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts" program, with a lively piano rendition of I Got Rhythm. But it wasn't until 1954, that a record company executive heard him playing piano in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, and signed him to a contract. His first, and still most famous, hit record was Autumn Leaves. By 1968 he had recorded 52 albums, and sold nearly 15 million records. At 43, he became the best-selling instrumentalist of all time.

Roger Williams, name borrower, Farragut Naval Training Station recruit, ISU graduate, and world renowned pianist and composer passed away in 2011.

#rogerwilliams #Farragut #FNTS

Weertz was one of a handful of Farragut recruits who received part of their training at what was then the University of Idaho Southern Branch in Pocatello. He must have liked the city, because he came back after the war to attend college. He received a BA in music from ISU, then went on to get a Master's from Drake University. He studied further at Julliard in New York.

For whatever reason, Weertz decided to change his name while living in Pocatello. He allegedly pulled out a telephone book and ran his finger down the columns until he found one he liked. That name was Roger Williams.

There was only one Roger Williams in the phonebook at that time, according to the Roger Williams I knew. My friend, Roger, was a long-time Fish and Game employee and gained some measure of fame, along with Syd Tate, by charting out Idaho’s Centennial Trail.

The faux or, perhaps better-said, newly named Roger Williams gained quite a bit of fame in his time.

First, he won "Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts" program, with a lively piano rendition of I Got Rhythm. But it wasn't until 1954, that a record company executive heard him playing piano in a Manhattan cocktail lounge, and signed him to a contract. His first, and still most famous, hit record was Autumn Leaves. By 1968 he had recorded 52 albums, and sold nearly 15 million records. At 43, he became the best-selling instrumentalist of all time.

Roger Williams, name borrower, Farragut Naval Training Station recruit, ISU graduate, and world renowned pianist and composer passed away in 2011.

#rogerwilliams #Farragut #FNTS

Published on February 12, 2019 02:18

February 10, 2019

An Idaho Olympic Champ

Georgia Coleman, center in the photo, was born in St. Maries, Idaho. She was an Olympic champion, but the Idaho Statesman didn’t make the Idaho connection when reporting on her prowess in the pool at the time so she may not have lived long in the state.

Coleman won the silver medal in the 10-metre platform and the bronze medal in the 3-metre springboard competition in 1928 in Amsterdam. Four years later, in Los Angels she won the gold medal in the 3-metre springboard event and the silver medal in the 10-metre platform competition. She dominated diving competition for several years.

Coleman contracted polio in 1937. She recovered enough to start swimming again, but two years later died from polio-related pneumonia.

Georgia Coleman was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1966.

You can see Coleman demonstrating her dives by Googling Georgia Coleman (1933), and watching a short video called Graceful Eve.

#georgiacoleman

Coleman won the silver medal in the 10-metre platform and the bronze medal in the 3-metre springboard competition in 1928 in Amsterdam. Four years later, in Los Angels she won the gold medal in the 3-metre springboard event and the silver medal in the 10-metre platform competition. She dominated diving competition for several years.

Coleman contracted polio in 1937. She recovered enough to start swimming again, but two years later died from polio-related pneumonia.

Georgia Coleman was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1966.

You can see Coleman demonstrating her dives by Googling Georgia Coleman (1933), and watching a short video called Graceful Eve.

#georgiacoleman

Published on February 10, 2019 04:00

February 9, 2019

The 1974 Kootenai War

Indians fought losing wars with the United States Government for years during the settlement of the West. They fought for their way of life, their traditions, and mostly for their land.

What might have been the last Indian war was about land, too. No bullets were fired, nor arrows unleashed. The war was declared by a woman, Amy Trice, the chair of the Kootenai Tribe, on September 20, 1974.

The Kootenai had been unrepresented at the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate of 1855. Never-the-less that treaty took away any claim they had to their aboriginal lands and without compensation. They had no reservation.

That lack of representation was something of a Catch 22. Most tribes in the United States are prohibited from declaring war on the country, a clause laid out in multiple treaties. But the Kootenai had never signed a treaty. They weren’t even recognized as a tribe by the U.S.

So, after living in grinding poverty with no land base for 120 years, war it was. To underscore their claim of aboriginal lands, the Kootenai began waving cars over and collecting a voluntary fee of 10 cents to cross their lands on the highway north and south of Bonners Ferry. There was much local resentment of the action and rumors of weaponry being smuggled to the Indians. Members from several tribes began gathering near Bonners Ferry in support of the Kootenai.

The 67-member tribe suggested they would soon begin charging a 50 cent per day business tax and 10 cents per day for dwellings situated on their aboriginal lands.

The Kootenai’s call it a “War of the pen.” The publicity gained by declaring war and charging tolls got the attention of the press, the public, and politicians more than anything the Tribe had tried. In the end, President Gerald Ford signed legislation granting the Tribe 12.5 acres of land surrounding a mission. In the Hellgate Treaty, an estimated 1.6 million acres of land had been taken from the Kootenai.

The 12.5 acres doesn’t seem like much, but it gave the Kootenai a reservation and the legislation recognized the Tribe, clearing the way for eligibility for some government funding. Today, the Kootenai Tribe holds about 2,500 acres of land. They are dedicated to habitat restoration, particularly for sturgeon and burbot.

Amy Trice, the woman who declared war against the U.S., passed away in 2011 at age 75, a heroine to her people.

Image: Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

#kootenai #amytrice #kootenaitribe

Amy Trice. Photo courtesy of Idaho Public Television.

Amy Trice. Photo courtesy of Idaho Public Television.

What might have been the last Indian war was about land, too. No bullets were fired, nor arrows unleashed. The war was declared by a woman, Amy Trice, the chair of the Kootenai Tribe, on September 20, 1974.

The Kootenai had been unrepresented at the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate of 1855. Never-the-less that treaty took away any claim they had to their aboriginal lands and without compensation. They had no reservation.

That lack of representation was something of a Catch 22. Most tribes in the United States are prohibited from declaring war on the country, a clause laid out in multiple treaties. But the Kootenai had never signed a treaty. They weren’t even recognized as a tribe by the U.S.

So, after living in grinding poverty with no land base for 120 years, war it was. To underscore their claim of aboriginal lands, the Kootenai began waving cars over and collecting a voluntary fee of 10 cents to cross their lands on the highway north and south of Bonners Ferry. There was much local resentment of the action and rumors of weaponry being smuggled to the Indians. Members from several tribes began gathering near Bonners Ferry in support of the Kootenai.

The 67-member tribe suggested they would soon begin charging a 50 cent per day business tax and 10 cents per day for dwellings situated on their aboriginal lands.

The Kootenai’s call it a “War of the pen.” The publicity gained by declaring war and charging tolls got the attention of the press, the public, and politicians more than anything the Tribe had tried. In the end, President Gerald Ford signed legislation granting the Tribe 12.5 acres of land surrounding a mission. In the Hellgate Treaty, an estimated 1.6 million acres of land had been taken from the Kootenai.

The 12.5 acres doesn’t seem like much, but it gave the Kootenai a reservation and the legislation recognized the Tribe, clearing the way for eligibility for some government funding. Today, the Kootenai Tribe holds about 2,500 acres of land. They are dedicated to habitat restoration, particularly for sturgeon and burbot.

Amy Trice, the woman who declared war against the U.S., passed away in 2011 at age 75, a heroine to her people.

Image: Amy Trice, courtesy of Idaho Public Television. For more information on Trice and the Kootenai War, click here.

#kootenai #amytrice #kootenaitribe

Amy Trice. Photo courtesy of Idaho Public Television.

Amy Trice. Photo courtesy of Idaho Public Television.

Published on February 09, 2019 04:00