Rick Just's Blog, page 204

March 20, 2019

Alridge was a Dry Farm Town

The first thing you should know about Alridge is that you’re spelling it wrong. At least, someone thinks so. It has been called Alrich, Aldridge, All Ridge, and Aldrich in various mentions. It was called Cedar Creek until it came time to establish a post office there in 1915. Dewalde Durfee, who sent the application in to the U.S. Post Office Department, made that his first choice. For whatever reason the agency passed on that, but did pick one of Durfee’s alternate names, Alridge. That was appropriate because of the ridges scattered around the area.

If you plug the name Alridge into Google Maps the app will tell you to follow US 91 north from Blackfoot nearly to Firth, then take a right on Wolverine Road. Follow that almost to Wolverine Canyon for about 10 and a half miles. Take Blackfoot River Road to the right when you come to that and drive four more miles. At about the point where the road crosses Cedar Creek you’ll find a little fenced in area where descendants of homesteaders Clifford and Daphne Jemmett erected a marker some years ago (photo). Not much else is there anymore to tell the story of Alridge.

Clifford Jemmett’s parents, Henry and Lizzy, had their place in the Blackfoot River Canyon just below Alridge where a wide curve in the river left a strip of land where an orchard could be planted and cattle pastured. That area is called the Cove.

The Alridge Post Office, originally inside the Clifford Jemmett home, operated from 1915 to 1950. It was necessary because people were filing homestead claims on property in the area for the purpose of growing dryland grain. For a time, before the Great Depression, weather conditions were just right for that activity and grain sold for a good price. Deteriorating market conditions took away some of the incentive to farm. Cars and trucks shortened the distance between larger towns and Alridge, so there was less reason to live there. The community faded away, but dryland farms, now much larger, still operate on the benches above Cedar Creek.

While the community thrived, a school was a necessity. The tidy one-room Alridge School was built in 1915 and painted white with red trim. That color combination found its way to some other buildings in the little community, giving it a unique character. The school closed in 1948, but that wasn’t the end of its story. In 1999 the Alridge School was moved to North Bingham County Park near Shelley, where it serves today as an education museum, a typical example of a one-room school. Photos and stories inside the school help resuscitate Alridge a bit.

This article first appeared in the Monday, March 4 2019 edition of the Blackfoot Morning News.

If you plug the name Alridge into Google Maps the app will tell you to follow US 91 north from Blackfoot nearly to Firth, then take a right on Wolverine Road. Follow that almost to Wolverine Canyon for about 10 and a half miles. Take Blackfoot River Road to the right when you come to that and drive four more miles. At about the point where the road crosses Cedar Creek you’ll find a little fenced in area where descendants of homesteaders Clifford and Daphne Jemmett erected a marker some years ago (photo). Not much else is there anymore to tell the story of Alridge.

Clifford Jemmett’s parents, Henry and Lizzy, had their place in the Blackfoot River Canyon just below Alridge where a wide curve in the river left a strip of land where an orchard could be planted and cattle pastured. That area is called the Cove.

The Alridge Post Office, originally inside the Clifford Jemmett home, operated from 1915 to 1950. It was necessary because people were filing homestead claims on property in the area for the purpose of growing dryland grain. For a time, before the Great Depression, weather conditions were just right for that activity and grain sold for a good price. Deteriorating market conditions took away some of the incentive to farm. Cars and trucks shortened the distance between larger towns and Alridge, so there was less reason to live there. The community faded away, but dryland farms, now much larger, still operate on the benches above Cedar Creek.

While the community thrived, a school was a necessity. The tidy one-room Alridge School was built in 1915 and painted white with red trim. That color combination found its way to some other buildings in the little community, giving it a unique character. The school closed in 1948, but that wasn’t the end of its story. In 1999 the Alridge School was moved to North Bingham County Park near Shelley, where it serves today as an education museum, a typical example of a one-room school. Photos and stories inside the school help resuscitate Alridge a bit.

This article first appeared in the Monday, March 4 2019 edition of the Blackfoot Morning News.

Published on March 20, 2019 04:00

March 19, 2019

Roosevelt Lake

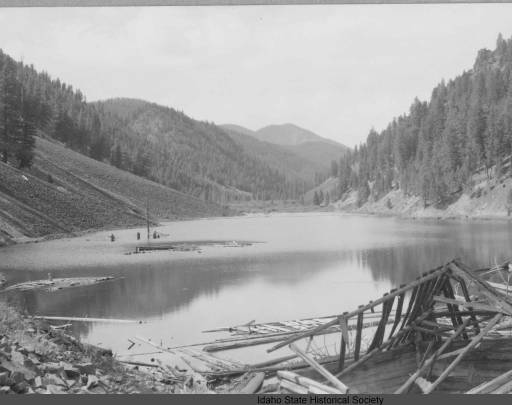

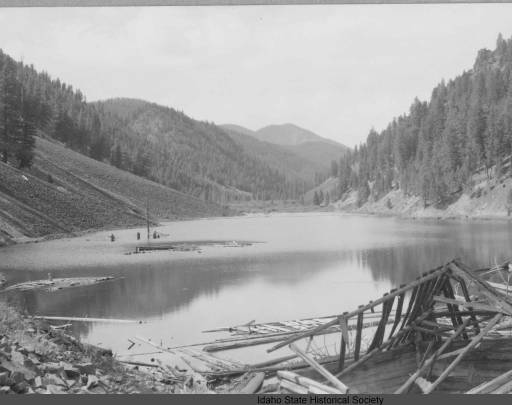

Named for Teddy Roosevelt, the mining town of Roosevelt, Idaho is a footnote in Idaho’s history of disasters. The ramshackle town, east of Yellowpine, started in 1902 when miners first came to the Thunder Mountain District on rumors of a major gold find. The Dewey Mine’s production fell far short of the rumors. It operated for five years, closing in 1907.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

Published on March 19, 2019 04:00

March 18, 2019

Harry's Conversion

There are enough stories about Harry Orchard to fill a hundred blog posts. Today’s is about how he found religion.

Harry Orchard is well-known in Idaho as the man who rigged the bomb on that Caldwell gate that killed Frank Steunenberg, former governor of Idaho. Less well-known is that Harry’s real name was Albert Edward Horsley, a one-time cheesemaker from Wooler, Ontario, Canada.

Orchard pleaded guilty to the murder and turned state’s evidence in the famous trial of “Big Bill” Haywood and Charles Moyer, both leaders in the Western Federation of Miners, and labor activist George Pettibone. Clarence Darrow got those men off, but Orchard went to prison, admitting to 26 murders.

Orchard’s conversion started before his sentencing in 1908. He had been moved to plead guilty by his reading of the Bible and was convinced it was the only way to save his soul. At first sentenced to hang, that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

In the early days of his sentence, Orchard received a visit from the 21-year-old son of Governor Steunenberg, Julian. The young man brought a packet of pamphlets and books associated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church on the behest of his mother, Eveline Belle Steunenberg. She and her children were church members, and she urged Orchard to “give his life fully to Christ.”

He did so, joining the Adventist faith. He was baptized January 1, 1909 at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Mrs. Steunenberg saw God’s hand in the assassination of her husband in a way that comforted her. It came out that Orchard had made three previous attempts to kill the man, all of which failed. On the day of the assassination, the former governor had told his family he was moved to worship with them. Though his death came just hours later, Mrs. Steunenberg came to believe God had stayed the hand of the assassin long enough to bring the governor into the fold. She would petition for Harry Orchard’s pardon and release in 1922.

Harry Orchard spent 46 years in Idaho’s prison system—though mostly not within the walls of the prison. That’s a story for another day. Orchard died April 13, 1954, at the age of 88. He was the longest serving prisoner in the system. His funeral service was conducted by the Boise Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Harry Orchard is well-known in Idaho as the man who rigged the bomb on that Caldwell gate that killed Frank Steunenberg, former governor of Idaho. Less well-known is that Harry’s real name was Albert Edward Horsley, a one-time cheesemaker from Wooler, Ontario, Canada.

Orchard pleaded guilty to the murder and turned state’s evidence in the famous trial of “Big Bill” Haywood and Charles Moyer, both leaders in the Western Federation of Miners, and labor activist George Pettibone. Clarence Darrow got those men off, but Orchard went to prison, admitting to 26 murders.

Orchard’s conversion started before his sentencing in 1908. He had been moved to plead guilty by his reading of the Bible and was convinced it was the only way to save his soul. At first sentenced to hang, that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

In the early days of his sentence, Orchard received a visit from the 21-year-old son of Governor Steunenberg, Julian. The young man brought a packet of pamphlets and books associated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church on the behest of his mother, Eveline Belle Steunenberg. She and her children were church members, and she urged Orchard to “give his life fully to Christ.”

He did so, joining the Adventist faith. He was baptized January 1, 1909 at the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Mrs. Steunenberg saw God’s hand in the assassination of her husband in a way that comforted her. It came out that Orchard had made three previous attempts to kill the man, all of which failed. On the day of the assassination, the former governor had told his family he was moved to worship with them. Though his death came just hours later, Mrs. Steunenberg came to believe God had stayed the hand of the assassin long enough to bring the governor into the fold. She would petition for Harry Orchard’s pardon and release in 1922.

Harry Orchard spent 46 years in Idaho’s prison system—though mostly not within the walls of the prison. That’s a story for another day. Orchard died April 13, 1954, at the age of 88. He was the longest serving prisoner in the system. His funeral service was conducted by the Boise Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Harry Orchard, right, raised hundreds of chickens and turkey at the old Idaho Penitentiary. He spent most of his 46 years at the prison living in a little house outside of the walls.

Published on March 18, 2019 04:00

March 17, 2019

Parking in Murphy

How small is it? That sounds like a joke set-up, rather than the beginning of a totally serious story about Murphy, Idaho and its famous parking meter.

In January, 1956, the Associated Press fed a story to their wire service subscribers about Murphy, Idaho’s solitary parking meter. Murphy, at the time, had only 31 residents, which probably made it the county seat with the smallest population in the country. Since then population has skyrocketed to nearly 100 people.

But, about that parking meter… Kenneth Downing, then the county clerk, thought it might be a good gag to install a parking meter in front of a wire gate at the courthouse that people were always blocking with their cars. It seemed to cut down on the pesky parking, but it didn’t raise a lot of money. It didn’t even work, at first. City fathers, or city jokesters, or someone later repaired it so they could collect coins. Theoretically.

Downing appeared in the AP photo that accompanied the story tying his horse up to the meter. The article pointed out that there were probably more horses in the county than cars, anyway.

You can still visit Owyhee County’s only parking meter today, more than 50 years later, making this one long-running joke.

In January, 1956, the Associated Press fed a story to their wire service subscribers about Murphy, Idaho’s solitary parking meter. Murphy, at the time, had only 31 residents, which probably made it the county seat with the smallest population in the country. Since then population has skyrocketed to nearly 100 people.

But, about that parking meter… Kenneth Downing, then the county clerk, thought it might be a good gag to install a parking meter in front of a wire gate at the courthouse that people were always blocking with their cars. It seemed to cut down on the pesky parking, but it didn’t raise a lot of money. It didn’t even work, at first. City fathers, or city jokesters, or someone later repaired it so they could collect coins. Theoretically.

Downing appeared in the AP photo that accompanied the story tying his horse up to the meter. The article pointed out that there were probably more horses in the county than cars, anyway.

You can still visit Owyhee County’s only parking meter today, more than 50 years later, making this one long-running joke.

Published on March 17, 2019 04:00

March 16, 2019

The Deepest Canyon, Maybe

What this country needs is more arguing, said nobody in the past six months. Nevertheless, this post will probably start a few arguments.

Superlatives fascinate us, if the Guinness Book of World Records is any indication. We want to know the biggest, the smallest, the widest, the most… And, we certainly want to know the deepest. One of Idaho’s claims to fame is having the deepest canyon in North America. Hells Canyon, when measured from the top of He Devil Mountain to the splashing Snake River is 7,993 feet. At least, that’s the number given most often.

But, is that the deepest? Some folks claim that Kings Canyon in California is actually the deepest, at 8,200 feet. At a glance, Kings Canyon looks like the easy winner. But how does one measure a canyon? When you think of a canyon, your mind probably goes to Grand Canyon with its sheer cliffs and brilliant colors. Now THAT’S a canyon! Yet, Grand Canyon, at its deepest is only about 6,000 feet. There’s no real issue about measuring the Grand Canyon. You might be able to use a plumb bob in spots and more than a mile of string, dropping it straight down. You couldn’t do that at Hells Canyon, because the point you measure from is the highest point in the Seven Devils Range, which is more than five miles from the river, as the eagle flies.

In California, Spanish Mountain is 8,200 feet above the confluence of the Middle and South forks of the King River, which is just less than 5 miles away. A plumb bob wouldn’t work there, either.

Now, I know they don’t use a string and a weight to determine the difference in elevation between a river and the top of a peak. I use the plumb bob image just to make a point. That point is a question. What is a canyon? Does a gorge count as a gorge if only one side has high cliffs? If an asymmetrical canyon is okay with you, then Kings Canyon is probably your favorite for the deepest gorge. The mountains across from Spanish Mountain are about 2,200 feet above the river.

Meanwhile, back in Idaho, the mountains on the Oregon side of the Snake are more than a mile above the river. That seems a little more gorge-like to me.

Hells Canyon wins the internet, with most sites listing it as the deepest. Wikipedia calls it the deepest in North America at 7,933 feet, while mentioning in passing on the Kings Canyon page that it is “one of the deepest in North America” at 8,200 feet.

To muddy the canyon waters a bit further, some sites claim that Copper Canyon in Mexico is the deepest in North America, though with no substantiation.

Discuss amongst yourselves.

#deepestgorge #deepestcanyon #hellscanyon

Superlatives fascinate us, if the Guinness Book of World Records is any indication. We want to know the biggest, the smallest, the widest, the most… And, we certainly want to know the deepest. One of Idaho’s claims to fame is having the deepest canyon in North America. Hells Canyon, when measured from the top of He Devil Mountain to the splashing Snake River is 7,993 feet. At least, that’s the number given most often.

But, is that the deepest? Some folks claim that Kings Canyon in California is actually the deepest, at 8,200 feet. At a glance, Kings Canyon looks like the easy winner. But how does one measure a canyon? When you think of a canyon, your mind probably goes to Grand Canyon with its sheer cliffs and brilliant colors. Now THAT’S a canyon! Yet, Grand Canyon, at its deepest is only about 6,000 feet. There’s no real issue about measuring the Grand Canyon. You might be able to use a plumb bob in spots and more than a mile of string, dropping it straight down. You couldn’t do that at Hells Canyon, because the point you measure from is the highest point in the Seven Devils Range, which is more than five miles from the river, as the eagle flies.

In California, Spanish Mountain is 8,200 feet above the confluence of the Middle and South forks of the King River, which is just less than 5 miles away. A plumb bob wouldn’t work there, either.

Now, I know they don’t use a string and a weight to determine the difference in elevation between a river and the top of a peak. I use the plumb bob image just to make a point. That point is a question. What is a canyon? Does a gorge count as a gorge if only one side has high cliffs? If an asymmetrical canyon is okay with you, then Kings Canyon is probably your favorite for the deepest gorge. The mountains across from Spanish Mountain are about 2,200 feet above the river.

Meanwhile, back in Idaho, the mountains on the Oregon side of the Snake are more than a mile above the river. That seems a little more gorge-like to me.

Hells Canyon wins the internet, with most sites listing it as the deepest. Wikipedia calls it the deepest in North America at 7,933 feet, while mentioning in passing on the Kings Canyon page that it is “one of the deepest in North America” at 8,200 feet.

To muddy the canyon waters a bit further, some sites claim that Copper Canyon in Mexico is the deepest in North America, though with no substantiation.

Discuss amongst yourselves.

#deepestgorge #deepestcanyon #hellscanyon

Published on March 16, 2019 04:00

March 15, 2019

The Firth Record

Chances are you’ve never heard of The Firth Record. It was the town paper of Firth, publishing from 1945 into the early 1950s. Copies of the old paper are so rare that the Idaho State Historical Society doesn’t have any in their microfilm collection at the state archives. I’ve recently come into possession of 26 editions of the paper, thanks to preservation-minded members of my family, particularly Kathy Christiansen. I’ve asked the Historical Society to scan them for the archives. Once that’s done, they will be donated to the Bingham County Historical Society.

Meanwhile, I ran across a surprising claim to fame for The Firth Record. In a retrospective published in the January 28, 1949 edition, the editor noted that one of the “extras” the paper had published drew “acclaim all over the nation, as the first to hit the streets, after the memorable Japanese surrender, marking the end of hostilities in a war torn world.”

Why? The editor explained. “Four months after the war’s end, The Firth Record was given national and international notoriety, with the announcement that it was the ‘firstest’ among the firsts. This was disclosed by the Publishers Auxiliary, a weekly newspaper published in Chicago.”

So, a Firth first. Further, the first Firthian to read the paper was Harold Brighton, who had it in his hands two minutes after it came off the press.

That moment of fame is gratifying to those of us from Firth who have endured jokes over the years such as, “Firth? Is that near Thecond?”

Meanwhile, I ran across a surprising claim to fame for The Firth Record. In a retrospective published in the January 28, 1949 edition, the editor noted that one of the “extras” the paper had published drew “acclaim all over the nation, as the first to hit the streets, after the memorable Japanese surrender, marking the end of hostilities in a war torn world.”

Why? The editor explained. “Four months after the war’s end, The Firth Record was given national and international notoriety, with the announcement that it was the ‘firstest’ among the firsts. This was disclosed by the Publishers Auxiliary, a weekly newspaper published in Chicago.”

So, a Firth first. Further, the first Firthian to read the paper was Harold Brighton, who had it in his hands two minutes after it came off the press.

That moment of fame is gratifying to those of us from Firth who have endured jokes over the years such as, “Firth? Is that near Thecond?”

Published on March 15, 2019 04:00

March 14, 2019

The Forbidden Palace Fire

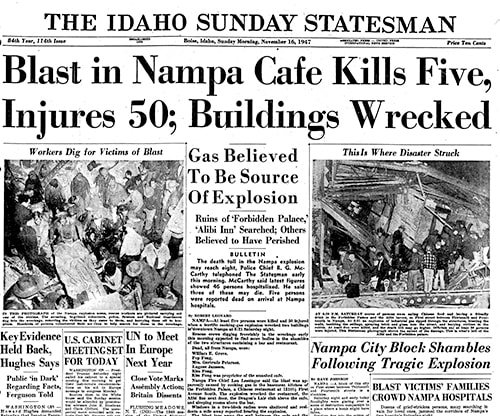

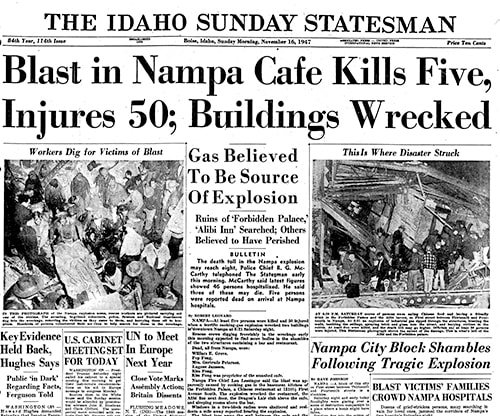

On Saturday night, November 16, 1947, a customer walked into the Forbidden Palace Chinese restaurant in Nampa, sat down at the counter and said, “I smell gas.”

The waitress replied, “I do, too.”

As if the conversation set it off, an enormous blast rocked the restaurant and the Alibi tavern next door. The floor dropped from beneath their feet and the ceiling came crashing down on top of them. For a moment, as the dust settled, there was silence. Then the screams began.

Fifty people were injured in the explosion and building collapse, six were killed.

The explosion occurred as a service truck was filling the butane gas tank the restaurant used for cooking.

Within a couple of weeks Knu Gas and Appliance of Boise and Nampa was running ads notifying customers that they had nothing to do with the explosion and extolling the safety of PROPANE gas and gas appliances.

By the end of the year, the “Superlatives of 47” feature in the Idaho Statesman listed the Forbidden Palace explosion the greatest Boise Valley disaster of the year.

Numerous law suits against the City of Nampa and the company that installed the butane tank were filed. The Idaho Supreme Court ultimately absolved the city of responsibility.

The blast increased calls for establishing a state fire marshal to formulate rules on LPG. Legislation was introduced and defeated in 1948. It wasn’t until 1982 that the first state fire marshal was named. The office is a division of the Idaho Department of Insurance. The director of that department selects the fire marshal with approval of the governor.

The waitress replied, “I do, too.”

As if the conversation set it off, an enormous blast rocked the restaurant and the Alibi tavern next door. The floor dropped from beneath their feet and the ceiling came crashing down on top of them. For a moment, as the dust settled, there was silence. Then the screams began.

Fifty people were injured in the explosion and building collapse, six were killed.

The explosion occurred as a service truck was filling the butane gas tank the restaurant used for cooking.

Within a couple of weeks Knu Gas and Appliance of Boise and Nampa was running ads notifying customers that they had nothing to do with the explosion and extolling the safety of PROPANE gas and gas appliances.

By the end of the year, the “Superlatives of 47” feature in the Idaho Statesman listed the Forbidden Palace explosion the greatest Boise Valley disaster of the year.

Numerous law suits against the City of Nampa and the company that installed the butane tank were filed. The Idaho Supreme Court ultimately absolved the city of responsibility.

The blast increased calls for establishing a state fire marshal to formulate rules on LPG. Legislation was introduced and defeated in 1948. It wasn’t until 1982 that the first state fire marshal was named. The office is a division of the Idaho Department of Insurance. The director of that department selects the fire marshal with approval of the governor.

Published on March 14, 2019 04:00

March 13, 2019

Ross Hall Girls

During World War II, more than 292,000 “boots” trained at Farragut Naval Training Station, north of Coeur d’Alene. Sandpoint, Idaho, photographer Ross Hall provided class photographs the boots could buy. The photographs included a list of those pictured. It was quite a production.

The shot below shows three “Ross Hall Girls,” who kept track of names of those in the pictures and took orders. They’re shown in their booths with a class lined up for a photograph in the background. Ross Hall himself probably took this picture. To give you an idea of the scale of this operation, In March 1944, a record 20,891 boots had their pictures taken.

Hundreds of company photos are on file today at Farragut State Park to help those wanting to know more about family members who went through training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

The shot below shows three “Ross Hall Girls,” who kept track of names of those in the pictures and took orders. They’re shown in their booths with a class lined up for a photograph in the background. Ross Hall himself probably took this picture. To give you an idea of the scale of this operation, In March 1944, a record 20,891 boots had their pictures taken.

Hundreds of company photos are on file today at Farragut State Park to help those wanting to know more about family members who went through training at Farragut Naval Training Station.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

The picture above is Company B, 11th Battalion, Third Regiment.

Published on March 13, 2019 04:00

March 12, 2019

Boise Foothills Growth

For the past 30 years or so there has been a tension in Boise between those who love a view, and those who love a view. People wanted to build houses along the Boise Front for the view it afforded of the city and beyond. Other Boise residents objected to houses popping up on the foothills and spoiling THEIR view of the Front. It wasn’t just the view that had those residents concerned. They thought the Boise Front had intrinsic values of its own, from wildlife habitat to recreation opportunities. There have been victories on both sides over the years, but the consensus now seems to be in favor of limiting growth in the foothills.

That’s why an article in the March-April 1953 edition of Scenic Idaho magazine caught my attention. Titled “Boise Takes to the Heights,” it led off with these paragraphs:

“The Boise Chamber of Commerce has a motto: Building a Better Boise—But if the present trek of its population continues to elevated home sites, this might well be changed to: “Building a Higher Boise.”

Nor are the regular residents the only ones lifting their eyes to the hills… Newcomers from California’s crowded population centers, from the Midwest and the East have found the city’s clime to their liking… Many of these seek “elbowroom” and gratify their need for it by constructing homes on hill and bench that are not altogether California or western ranch-house or modernistic—but which architects say may become the forerunner of a strictly “Idaho Home.”

Imagine, people moving to Idaho from California, of all places!

Among the realtors hawking homes in J.R. Simplot’s Boise Heights development (excellent homesites from $1,000) was Day Realty, run by Ernie Day. Day built his own home there. Today, with sensibilities about the foothills turned about 180 degrees from those of 1953, one might be tempted to grumble about entrepreneurs such as Ernie Day building homes where homes, perhaps, should never have been built. But I think Ernie can be given a bit of a pass on this one. He became an outspoken champion of Idaho’s special places and would play a key role in saving the Whiteclouds from mining in the early 70s.

The article ended with a sentence that would get many Boisean’s blood boiling today:

“Thus, Boise takes to the heights, and for a city continuing to increase in population, the surrounding hills and benches have provided a natural setting, and an outlet of new beauty without loss in utility.”

The photo is from the magazine article, which noted large windows set to provide a panoramic view to the southwest.

#boisegrowth

That’s why an article in the March-April 1953 edition of Scenic Idaho magazine caught my attention. Titled “Boise Takes to the Heights,” it led off with these paragraphs:

“The Boise Chamber of Commerce has a motto: Building a Better Boise—But if the present trek of its population continues to elevated home sites, this might well be changed to: “Building a Higher Boise.”

Nor are the regular residents the only ones lifting their eyes to the hills… Newcomers from California’s crowded population centers, from the Midwest and the East have found the city’s clime to their liking… Many of these seek “elbowroom” and gratify their need for it by constructing homes on hill and bench that are not altogether California or western ranch-house or modernistic—but which architects say may become the forerunner of a strictly “Idaho Home.”

Imagine, people moving to Idaho from California, of all places!

Among the realtors hawking homes in J.R. Simplot’s Boise Heights development (excellent homesites from $1,000) was Day Realty, run by Ernie Day. Day built his own home there. Today, with sensibilities about the foothills turned about 180 degrees from those of 1953, one might be tempted to grumble about entrepreneurs such as Ernie Day building homes where homes, perhaps, should never have been built. But I think Ernie can be given a bit of a pass on this one. He became an outspoken champion of Idaho’s special places and would play a key role in saving the Whiteclouds from mining in the early 70s.

The article ended with a sentence that would get many Boisean’s blood boiling today:

“Thus, Boise takes to the heights, and for a city continuing to increase in population, the surrounding hills and benches have provided a natural setting, and an outlet of new beauty without loss in utility.”

The photo is from the magazine article, which noted large windows set to provide a panoramic view to the southwest.

#boisegrowth

Published on March 12, 2019 04:00

March 11, 2019

Former Work Farm is now a Place to Play

See my latest column for Idaho Press.

Published on March 11, 2019 05:12