Rick Just's Blog, page 200

April 29, 2019

April 28, 2019

Winchester

The origin of town names in Idaho provides occasional fodder for these postings. One of the better-known stories is about the town of Winchester. That’s because the town makes a point of telling it, with an over-sized model of a Winchester rifle hanging across one of their streets for years. An image search reveals a similar rifle gracing the front of Winchester City Hall. Alert readers will no doubt tell me if the “street” rifle has been moved, or if there are now two big guns.

In any case, the story goes that when it came to naming the town someone decided to choose the moniker by counting the number of rifles bearing brand names and go with the most popular rifle brand. If there remains a tally to tell us how close the town came to being called Remington, I’m not aware of it.

The image below is from the November 26, 1909 edition of the Camas County Chronicle announcing the irresistible lots available in the newly named (1908) town of Winchester.

#winchester #winchesterlake #winchesteridaho

In any case, the story goes that when it came to naming the town someone decided to choose the moniker by counting the number of rifles bearing brand names and go with the most popular rifle brand. If there remains a tally to tell us how close the town came to being called Remington, I’m not aware of it.

The image below is from the November 26, 1909 edition of the Camas County Chronicle announcing the irresistible lots available in the newly named (1908) town of Winchester.

#winchester #winchesterlake #winchesteridaho

Published on April 28, 2019 04:00

April 27, 2019

You Do that Hoodoo that You Do so Well

The other day I was browsing through the Twenty-Third Biennial Report of the State Historical Society of Idaho published in 1922, as one does. It caught my attention that the report listed all the monuments in Idaho and associated with Idaho at the time. I skimmed through the list and descriptions to see if there might be blog fodder. Indeed. I will victimize you further with future posts but will restrain myself to a single monument for this one.

In fact, I’ll give only cursory attention to the monument mentioned because searching for more information on it led me down a path that with liberal use of unnecessary words will in itself be a blog.

See. I’ve already written 115 words without getting to the point. But I digress. But you knew that.

The monument that I wanted to research was the Sheepeater Monument. That monument, which I’ll tell you about in another post, was located near where Big Creek runs into the Salmon River. It’s a story worthy of a blog post, which I have already promised.

But today’s post, the one you’re reading, which has now run to 191 words without even approaching its subject, is about a “monument” I found while trying to do a little research on the aforementioned Sheepeater Monument.

Breaking out my copy of the trusty internet I did a Google image search for Sheepeater Monument, Idaho. What came up was an oddly shaped rock. It was actually more of a hoodoo which, now that the little ones have nodded off, I can proceed to describe.

The hoodoo in question, which was sometimes called Sheepeater’s Monument, is, as technical jargon would have it, really, really tall. I found a reference that said 70 feet. I don’t know. Photos show it towering over nearby trees. It is undeniably… let’s say tree-like, in that it is tall and narrow, but without the limbs one would usually find on a tall pine. A pole then. It’s like a pole. Eons ago some force, probably water followed later by wind, wore away layers of rock around it leaving a shaft of rock. And, to top it off, there is a large boulder resting impossibly on the summit of the hoodoo.

The formation has had some colorful names that I will leave up to you to imagine. It has a smaller pair of hoodoo companions nearby. This grouping of rude rocks at the head of Monumental Creek in Valley County is apparently why the creek is called that. We can be thankful for this unusual display of modesty on the part of the person who named it.

Photos of the formation are rare for a couple of reasons. The site is a bit challenging to find and hike to and getting the entire formation in a shot requires some clever positioning by the photographer. Alas, I did find one photo that may show the formation without its signature boulder on top. Say it isn’t so. Really. Let me know if you have recent, first-hand knowledge of the hoodoo. Rock or no rock, we await the revelation.

In fact, I’ll give only cursory attention to the monument mentioned because searching for more information on it led me down a path that with liberal use of unnecessary words will in itself be a blog.

See. I’ve already written 115 words without getting to the point. But I digress. But you knew that.

The monument that I wanted to research was the Sheepeater Monument. That monument, which I’ll tell you about in another post, was located near where Big Creek runs into the Salmon River. It’s a story worthy of a blog post, which I have already promised.

But today’s post, the one you’re reading, which has now run to 191 words without even approaching its subject, is about a “monument” I found while trying to do a little research on the aforementioned Sheepeater Monument.

Breaking out my copy of the trusty internet I did a Google image search for Sheepeater Monument, Idaho. What came up was an oddly shaped rock. It was actually more of a hoodoo which, now that the little ones have nodded off, I can proceed to describe.

The hoodoo in question, which was sometimes called Sheepeater’s Monument, is, as technical jargon would have it, really, really tall. I found a reference that said 70 feet. I don’t know. Photos show it towering over nearby trees. It is undeniably… let’s say tree-like, in that it is tall and narrow, but without the limbs one would usually find on a tall pine. A pole then. It’s like a pole. Eons ago some force, probably water followed later by wind, wore away layers of rock around it leaving a shaft of rock. And, to top it off, there is a large boulder resting impossibly on the summit of the hoodoo.

The formation has had some colorful names that I will leave up to you to imagine. It has a smaller pair of hoodoo companions nearby. This grouping of rude rocks at the head of Monumental Creek in Valley County is apparently why the creek is called that. We can be thankful for this unusual display of modesty on the part of the person who named it.

Photos of the formation are rare for a couple of reasons. The site is a bit challenging to find and hike to and getting the entire formation in a shot requires some clever positioning by the photographer. Alas, I did find one photo that may show the formation without its signature boulder on top. Say it isn’t so. Really. Let me know if you have recent, first-hand knowledge of the hoodoo. Rock or no rock, we await the revelation.

Published on April 27, 2019 04:00

April 26, 2019

White Bird Creek Bridge Collapse

Steel was in short supply during World War I. That apparently resulting in the drowning of a steer in 1931.

This is a photo of a collapsed bridge over the Salmon River at the mouth of White Bird Creek. The composite cantilever bridge was built during the war using as little steel as possible. Not enough steel, perhaps, as it collapsed under the weight of a herd of cattle being driven across it in 1931. Seventeen steers and one cowboy went into the Salmon. Sixteen steers and one cowboy came out, leaving one steer the casualty of a distant war.

This is a photo of a collapsed bridge over the Salmon River at the mouth of White Bird Creek. The composite cantilever bridge was built during the war using as little steel as possible. Not enough steel, perhaps, as it collapsed under the weight of a herd of cattle being driven across it in 1931. Seventeen steers and one cowboy went into the Salmon. Sixteen steers and one cowboy came out, leaving one steer the casualty of a distant war.

Published on April 26, 2019 04:00

April 25, 2019

Don't Bother to Apply

In 1864, Idaho was barely a territory. One writer for the Idaho Statesman noticed that many people were coming through Boise on their way to Oregon Territory, often without stopping.

In the August 20, 1864 editorial the writer lamented that people seemed to give up on Boise too soon. “A man can seldom see a chance to make money or start in business the first or second day he stops in a new place.”

The writer noted that “Most of the available land along the river is claimed, but there are many thousands of acres lying back that are not claimed which need only a moderate outlay of labor and capital to make as productive as could be desired.”

It would be a couple more decades before canal projects made many of those thousand acres bloom. Still, there was plenty of opportunity in the valley.

The editorial expressed an almost unlimited need for laborers. “You cannot stay in this town three days without finding something to do, and our word for it, you will ever after that have more on your hands than you can do.” Not every profession was needed, though. The editorial concluded with this: “If you want to practice law or physic, don’t stop, for we have more than enough of both. If you want to get into office and dabble in politics, for Heaven’s sake move on to some other country. We have a large population of that sort that we would be glad to export.”

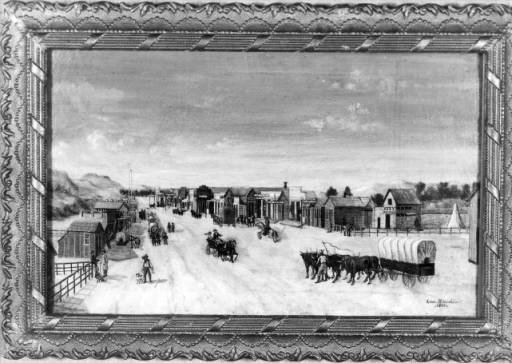

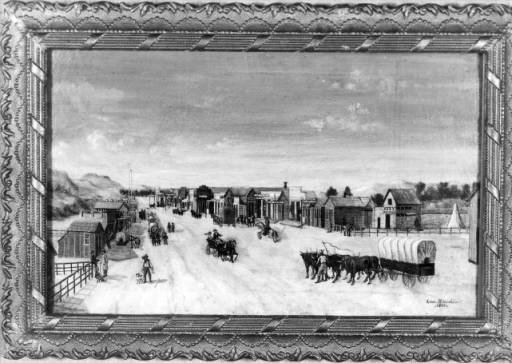

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

In the August 20, 1864 editorial the writer lamented that people seemed to give up on Boise too soon. “A man can seldom see a chance to make money or start in business the first or second day he stops in a new place.”

The writer noted that “Most of the available land along the river is claimed, but there are many thousands of acres lying back that are not claimed which need only a moderate outlay of labor and capital to make as productive as could be desired.”

It would be a couple more decades before canal projects made many of those thousand acres bloom. Still, there was plenty of opportunity in the valley.

The editorial expressed an almost unlimited need for laborers. “You cannot stay in this town three days without finding something to do, and our word for it, you will ever after that have more on your hands than you can do.” Not every profession was needed, though. The editorial concluded with this: “If you want to practice law or physic, don’t stop, for we have more than enough of both. If you want to get into office and dabble in politics, for Heaven’s sake move on to some other country. We have a large population of that sort that we would be glad to export.”

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Painting of Main Street, Boise, 1864, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on April 25, 2019 04:00

April 24, 2019

The Wealthiest Woman in the World

On Sunday, August 20, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran a full-page story with nine photos about a place in Island Park that was hosting a special guest, the “wealthiest woman in the world.” It was the first time Mrs. E.H. (Mary) Harriman would visit the state, but it would not be the last.

E.H. Harriman, “the biggest little railroad man the world had known,” had died in 1909, shortly after purchasing shares in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company. The place was already being called the Railroad Ranch because the men who bought the first 3,000 acres of the property in 1899 were associated with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Harriman, who ran Union Pacific Railroad, solidified that name with his purchase.

The article mentions, without naming them, that Mary Harriman’s sons came along with her. It would be those sons who had the most impact on Idaho, Averell by creating the Sun Valley Resort, and E. Roland by ultimately donating the Railroad Ranch to the State of Idaho to create Harriman State Park of Idaho (the latter two words in the name to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York).

The wealth of the Harrimans, the Guggenheims, and other investors did not escape the notice of the unnamed Statesman reporter, who wrote, “it is said that there is more wealth represented during the summer at Island Park than at any other point in the United States outside of Wall Street and Newport.”

Mrs. Harriman fell in love with the place, as did Averell and Roland.

The reporter predicted the future, when he (probably not she) wrote, “The world is open to Mrs. Harriman, but she selected Island Park as the place to spend her summer vacation in 1911; and it is an open secret that she will return next year and the next and indefinitely.”

Over the years there was no shortage of grousing from sportsmen and anglers who felt locked out of the Railroad Ranch, but ultimately saving this jewel of the Gem State was well worth it.

E.H. Harriman, “the biggest little railroad man the world had known,” had died in 1909, shortly after purchasing shares in the Island Park Land and Cattle Company. The place was already being called the Railroad Ranch because the men who bought the first 3,000 acres of the property in 1899 were associated with the Oregon Shortline Railroad. Harriman, who ran Union Pacific Railroad, solidified that name with his purchase.

The article mentions, without naming them, that Mary Harriman’s sons came along with her. It would be those sons who had the most impact on Idaho, Averell by creating the Sun Valley Resort, and E. Roland by ultimately donating the Railroad Ranch to the State of Idaho to create Harriman State Park of Idaho (the latter two words in the name to distinguish it from Harriman State Park in New York).

The wealth of the Harrimans, the Guggenheims, and other investors did not escape the notice of the unnamed Statesman reporter, who wrote, “it is said that there is more wealth represented during the summer at Island Park than at any other point in the United States outside of Wall Street and Newport.”

Mrs. Harriman fell in love with the place, as did Averell and Roland.

The reporter predicted the future, when he (probably not she) wrote, “The world is open to Mrs. Harriman, but she selected Island Park as the place to spend her summer vacation in 1911; and it is an open secret that she will return next year and the next and indefinitely.”

Over the years there was no shortage of grousing from sportsmen and anglers who felt locked out of the Railroad Ranch, but ultimately saving this jewel of the Gem State was well worth it.

Published on April 24, 2019 04:00

April 23, 2019

That Female Dentist

The August 27, 1892 edition of the Idaho Statesman had a note about the first woman dentist in the world. Henrietta Hirschfeldt was said to have graduated in 1869 from Pennsylvania College. This was apparently as common as roller skates on a goose, thus worthy of the mention.

When, in 1906, Boise was under threat of having its own distaff dentist, the Statesman felt it necessary to assure readers that Carrie Berthaumm, DDS, was probably physically capable of extracting a tooth. “She is a well built woman of—well, probably 20 or over, and appears eminently capable of handling any refractory molars that she might encounter without calling in the assistance of the janitor of her building, or using a block and tackle.”

That snide remark aside, Berthaumm did practice dentistry in Boise for many years with little further notice from the local paper, save for the weekly ads she purchased announcing her practice.

As if the sarcastic reporter who announced the beginning of her practice were prescient, Dr. Berthaumm did employ a janitor. He made the news because of dentistry, though not for helping her pull teeth. In June 1917, the janitor discovered that Berthaumm’s office had been broken into. Nothing seemed to be missing, but the culprit had left something behind. The janitor found a good-sized piece of gold on the floor. Knowing that Berthaumm did not handle gold filings, he took the little treasure to her colleague, Dr. Cohn, who discovered his desk drawer had been jimmied and the gold within stolen. All the dental offices in town had been hit over the weekend by the sloppy burglar, who took what gold he or she could find but left the costlier platinum behind.

When, in 1906, Boise was under threat of having its own distaff dentist, the Statesman felt it necessary to assure readers that Carrie Berthaumm, DDS, was probably physically capable of extracting a tooth. “She is a well built woman of—well, probably 20 or over, and appears eminently capable of handling any refractory molars that she might encounter without calling in the assistance of the janitor of her building, or using a block and tackle.”

That snide remark aside, Berthaumm did practice dentistry in Boise for many years with little further notice from the local paper, save for the weekly ads she purchased announcing her practice.

As if the sarcastic reporter who announced the beginning of her practice were prescient, Dr. Berthaumm did employ a janitor. He made the news because of dentistry, though not for helping her pull teeth. In June 1917, the janitor discovered that Berthaumm’s office had been broken into. Nothing seemed to be missing, but the culprit had left something behind. The janitor found a good-sized piece of gold on the floor. Knowing that Berthaumm did not handle gold filings, he took the little treasure to her colleague, Dr. Cohn, who discovered his desk drawer had been jimmied and the gold within stolen. All the dental offices in town had been hit over the weekend by the sloppy burglar, who took what gold he or she could find but left the costlier platinum behind.

Published on April 23, 2019 04:00

April 22, 2019

999 and Counting

What’s with all those springs, and are there really a thousand of them?

Oregon Trail pioneers came up with the name Thousand Springs. They likely didn’t count them. The springs tumble out of the canyon walls on the (roughly) north side of the Snake River from (again, roughly) Niagara Springs northwest of Buhl to the springs that fill Billingsley Creek at Hagerman. Many of the springs, which run a steady 58 degrees, have been captured for trout production or production of power, so they are less spectacular to view today than they were before the turn to the Twentieth Century.

But where do they come from? That was a puzzlement to the pioneers who named them, but geologists have it figured out. Much of the Snake River Plain consists of fractured basalt. Over the eons rain and snowmelt found its way through the cracks, filling them up much the way a sponge absorbs water. Water from as far away as the southern reaches of Yellowstone National Park has been seeping into the aquifer for thousands of years. The Lost River isn’t so much lost as it is hiding. It dives down into those cracks so thoroughly that it disappears.

The Snake River, with a bit of help from the Bonneville Flood, has been carving its canyons into that basalt, eroding away the “foot” of it and giving the water a chance to drain. Those are the springs along the canyon wall. There are also springs beneath the river, such as crystal clear Blue Heart Springs.

There may have been something of a balance of water going in and water coming out at one time. Now, water pumped for irrigation is depleting the aquifer faster than nature can fill it up. That’s why the springs have measurably diminished over the past few decades.

The picture shows the main Thousand Springs site near Hagerman sometime before 1910, when construction of the concrete capture structure was completed. This is how it would have looked to the pioneers who named it.

#thousandsprings

Oregon Trail pioneers came up with the name Thousand Springs. They likely didn’t count them. The springs tumble out of the canyon walls on the (roughly) north side of the Snake River from (again, roughly) Niagara Springs northwest of Buhl to the springs that fill Billingsley Creek at Hagerman. Many of the springs, which run a steady 58 degrees, have been captured for trout production or production of power, so they are less spectacular to view today than they were before the turn to the Twentieth Century.

But where do they come from? That was a puzzlement to the pioneers who named them, but geologists have it figured out. Much of the Snake River Plain consists of fractured basalt. Over the eons rain and snowmelt found its way through the cracks, filling them up much the way a sponge absorbs water. Water from as far away as the southern reaches of Yellowstone National Park has been seeping into the aquifer for thousands of years. The Lost River isn’t so much lost as it is hiding. It dives down into those cracks so thoroughly that it disappears.

The Snake River, with a bit of help from the Bonneville Flood, has been carving its canyons into that basalt, eroding away the “foot” of it and giving the water a chance to drain. Those are the springs along the canyon wall. There are also springs beneath the river, such as crystal clear Blue Heart Springs.

There may have been something of a balance of water going in and water coming out at one time. Now, water pumped for irrigation is depleting the aquifer faster than nature can fill it up. That’s why the springs have measurably diminished over the past few decades.

The picture shows the main Thousand Springs site near Hagerman sometime before 1910, when construction of the concrete capture structure was completed. This is how it would have looked to the pioneers who named it.

#thousandsprings

Published on April 22, 2019 04:00

April 21, 2019

The Rescue Mine

In 1890 the Idaho World reported a “curious story” about a mining operation in the Coeur d’Alenes. Two men, Thomas Burke and Delaine Llewellyn had discovered a promising lead that set them to digging on a peak known then as Welshman’s Point.

Hoping to find a rich vein of gold ore they succeeded in tunneling a distance of 171 feet. The two slept deep in their mine because it was the dead of winter. On January 13 a snow slide rammed snow and debris a hundred feet deep into the entrance of the tunnel.

The men had spent a couple of years digging rock and hauling it out of the mountain to make the tunnel. Now they were faced with digging a hundred feet of snow from within the mine to reach the outside world.

Burke and Llewellyn had food enough for six days. Water wasn’t a problem. They would not soon be short of melted snow. They began digging, carrying snow back into the tunnel behind them and dumping it on the rock floor. They dug to the point of exhaustion, toiling for five days.

The men were on the point of giving up when they saw a faint light in the snow. Minutes later a dozen miners broke through from the other side.

So thrilled were they with their rescue, that Burke and Llewellyn gave their rescuers equal shares in the mine when they struck a rich vein a few days later. It would be known from then on as the Rescue Mine.

Hoping to find a rich vein of gold ore they succeeded in tunneling a distance of 171 feet. The two slept deep in their mine because it was the dead of winter. On January 13 a snow slide rammed snow and debris a hundred feet deep into the entrance of the tunnel.

The men had spent a couple of years digging rock and hauling it out of the mountain to make the tunnel. Now they were faced with digging a hundred feet of snow from within the mine to reach the outside world.

Burke and Llewellyn had food enough for six days. Water wasn’t a problem. They would not soon be short of melted snow. They began digging, carrying snow back into the tunnel behind them and dumping it on the rock floor. They dug to the point of exhaustion, toiling for five days.

The men were on the point of giving up when they saw a faint light in the snow. Minutes later a dozen miners broke through from the other side.

So thrilled were they with their rescue, that Burke and Llewellyn gave their rescuers equal shares in the mine when they struck a rich vein a few days later. It would be known from then on as the Rescue Mine.

Published on April 21, 2019 04:00

April 20, 2019

New Book About Fearless Farris

He ran his first gas station in 1936 when he was only 20. That one was in Twin Falls.

After returning from service in WWII, Lind thought up a way to make his Boise service station famous. He scattered humorous signs all over southern Idaho to perk up drivers bored with many miles of sagebrush. One side advertised his growing number of Stinker Stations, while the other side offered humor, such as, in a field of lava rock (melon gravel left over from the Bonneville Flood), “Petrified watermelon. Take one home to your mother-in-law.”

During an Ad Club luncheon in Boise in 1948, Lind told about his three pet skunks, Cleo, Theo, and B.O., and how often people told him they had pet skunks when they were kids, which led Lind to postulate that 80 percent of Boiseans had pet skunks at one time. He told stories about people who would stop in to talk about his signs, often bringing one of those petrified watermelons to him. One of his favorites was a sign that said “No fishing within 400 yards.” It was placed miles from any drop of water. Lind said people would stop a ways down the road, turn around, and take another look. One guy allegedly walked half a mile down a dry wash looking for fishing country.

Lind got into the humorous sign business almost by accident. In 1946, with the war behind him, he tried to buy exterior plywood to advertise his service station, but only interior plywood was available. That meant both sides had to be painted to preserve the wood. Lind was quoted in the Idaho Statesman, saying, “As long as the back side of the sign was painted, I got the idea of putting humor or curiosity catching remarks on the back side”.

Some of those remarks include:

"Lava is free. Make your own soap."

"This area is for the birds. It's fowl territory."

"Nudist area. (Keep your eyes on the road.)"

"Sheep herders headed for town have right of way."

"For a fast pickup, pass a state patrolman."

At one time, there were about 150 Stinker Station signs between Green River, Wyoming and Jordan Valley, Oregon. Farris Lind came up with the humor for every one of them.

Lind contracted polio in 1963. He continued to run his company from an iron lung after that, never losing his trademark sense of humor.

He got a few complaints about his signs. Several people didn’t cotton to his sign outside of Salt Lake City that declared “Salt Lake City is full of lonely, beautiful women.” To avoid offending anyone, he had the word “lonely” removed. A similar sign about the women near Glenns Ferry prompted someone to scrawl “Where?” across it.

One of my personal favorites is still standing near Beeches Corner in Idaho Falls. It says, “Warning to tourists: Do not laugh at the natives.” About a billion years ago I was riding in a car with a fellow ten-year-old, he saw the sign and turned to me in wonder saying, “Are there NATIVES around here!?”

Fearless Farris Lind passed away in 1983. My new book about Farris Lind is called Fearless. Join me at the launch party on May 2, 7 pm at Rediscovered Books in Boise, if you can.

#Fearless #fearlessfarris #farrislind #stinkerstations

Farris Lind seems skeptical about this can of Skunk Oil. The photo, taken at one of his Salt Lake City stations, is used by permission of the Utah State Historical Society.

Farris Lind seems skeptical about this can of Skunk Oil. The photo, taken at one of his Salt Lake City stations, is used by permission of the Utah State Historical Society.

After returning from service in WWII, Lind thought up a way to make his Boise service station famous. He scattered humorous signs all over southern Idaho to perk up drivers bored with many miles of sagebrush. One side advertised his growing number of Stinker Stations, while the other side offered humor, such as, in a field of lava rock (melon gravel left over from the Bonneville Flood), “Petrified watermelon. Take one home to your mother-in-law.”

During an Ad Club luncheon in Boise in 1948, Lind told about his three pet skunks, Cleo, Theo, and B.O., and how often people told him they had pet skunks when they were kids, which led Lind to postulate that 80 percent of Boiseans had pet skunks at one time. He told stories about people who would stop in to talk about his signs, often bringing one of those petrified watermelons to him. One of his favorites was a sign that said “No fishing within 400 yards.” It was placed miles from any drop of water. Lind said people would stop a ways down the road, turn around, and take another look. One guy allegedly walked half a mile down a dry wash looking for fishing country.

Lind got into the humorous sign business almost by accident. In 1946, with the war behind him, he tried to buy exterior plywood to advertise his service station, but only interior plywood was available. That meant both sides had to be painted to preserve the wood. Lind was quoted in the Idaho Statesman, saying, “As long as the back side of the sign was painted, I got the idea of putting humor or curiosity catching remarks on the back side”.

Some of those remarks include:

"Lava is free. Make your own soap."

"This area is for the birds. It's fowl territory."

"Nudist area. (Keep your eyes on the road.)"

"Sheep herders headed for town have right of way."

"For a fast pickup, pass a state patrolman."

At one time, there were about 150 Stinker Station signs between Green River, Wyoming and Jordan Valley, Oregon. Farris Lind came up with the humor for every one of them.

Lind contracted polio in 1963. He continued to run his company from an iron lung after that, never losing his trademark sense of humor.

He got a few complaints about his signs. Several people didn’t cotton to his sign outside of Salt Lake City that declared “Salt Lake City is full of lonely, beautiful women.” To avoid offending anyone, he had the word “lonely” removed. A similar sign about the women near Glenns Ferry prompted someone to scrawl “Where?” across it.

One of my personal favorites is still standing near Beeches Corner in Idaho Falls. It says, “Warning to tourists: Do not laugh at the natives.” About a billion years ago I was riding in a car with a fellow ten-year-old, he saw the sign and turned to me in wonder saying, “Are there NATIVES around here!?”

Fearless Farris Lind passed away in 1983. My new book about Farris Lind is called Fearless. Join me at the launch party on May 2, 7 pm at Rediscovered Books in Boise, if you can.

#Fearless #fearlessfarris #farrislind #stinkerstations

Farris Lind seems skeptical about this can of Skunk Oil. The photo, taken at one of his Salt Lake City stations, is used by permission of the Utah State Historical Society.

Farris Lind seems skeptical about this can of Skunk Oil. The photo, taken at one of his Salt Lake City stations, is used by permission of the Utah State Historical Society.

Published on April 20, 2019 04:00