Rick Just's Blog, page 209

January 29, 2019

The Idaho UFO Connection

Individual Idahoans are responsible for many things we take for granted today, from TV to Teflon. Oh, and flying saucers, of course.

It was Tuesday, June 24th, 1947. Boise businessman Kenneth Arnold was flying near Mt. Rainier in Washington State, looking for a downed Marine Corps transport plane. Arnold, an experienced pilot, saw something in the fading sunlight that he had never seen before.

At an altitude of 9,200 feet he spotted a chain of objects weaving in the air, one after another. For a moment, he thought it might be a formation of geese--but at that altitude? Then he saw the sun reflect from the objects, suggesting that they might be metal.

The nine objects didn't seem to be airplanes, though. They had no wings; no tail fins. A drawing Arnold made of one object looks like the shape a windshield wiper would leave arcing through raindrops. That shape caught the imagination of the country. Other reports came in from across the nation--reports of "flying saucers."

The term "flying saucers" came from that sighting of unidentified flying objects. The modern age of UFOs began on that evening in 1947 when Boisean Kenneth Arnold, looking for a downed aircraft, saw something strange, instead.

The sighting gave Arnold a degree of fame he never sought. He became something of a celebrity among UFO buffs, and was the featured speaker when the first International UFO Congress met in 1977. He died a few years later, never certain of what he saw, but certain he saw something.

#idahohistory #ufos #flyingsaucers Kenneth Arnold and an artist's representation of what a UFO might look like.

Kenneth Arnold and an artist's representation of what a UFO might look like.

It was Tuesday, June 24th, 1947. Boise businessman Kenneth Arnold was flying near Mt. Rainier in Washington State, looking for a downed Marine Corps transport plane. Arnold, an experienced pilot, saw something in the fading sunlight that he had never seen before.

At an altitude of 9,200 feet he spotted a chain of objects weaving in the air, one after another. For a moment, he thought it might be a formation of geese--but at that altitude? Then he saw the sun reflect from the objects, suggesting that they might be metal.

The nine objects didn't seem to be airplanes, though. They had no wings; no tail fins. A drawing Arnold made of one object looks like the shape a windshield wiper would leave arcing through raindrops. That shape caught the imagination of the country. Other reports came in from across the nation--reports of "flying saucers."

The term "flying saucers" came from that sighting of unidentified flying objects. The modern age of UFOs began on that evening in 1947 when Boisean Kenneth Arnold, looking for a downed aircraft, saw something strange, instead.

The sighting gave Arnold a degree of fame he never sought. He became something of a celebrity among UFO buffs, and was the featured speaker when the first International UFO Congress met in 1977. He died a few years later, never certain of what he saw, but certain he saw something.

#idahohistory #ufos #flyingsaucers

Kenneth Arnold and an artist's representation of what a UFO might look like.

Kenneth Arnold and an artist's representation of what a UFO might look like.

Published on January 29, 2019 04:00

January 28, 2019

Wait, is that Him!?

The burning question in Boise on Valentine’s Day, 1943, was “is Jimmy Stewart really here?” The Idaho Statesman that day reported in its About Town column that it is was a rumor. “But that didn’t prevent Boise’s female population from dreaming, wondering, anticipating—and taking a good second look at every lieutenant they passed on the street.”

On page one of the same edition, the story read, “He’s Jimmy Stewart to millions of movie fans, but at Gowen Field Saturday he registered as First Lt. James M. Stewart, and on the routine registration forms, in the listing his occupation in civilian life he placed a question mark after the word ‘actor.’”

Stewart had been determined to serve his country. When he tried to enlist in the army, they turned him down because he was too skinny. At 6-foot-3, he tipped the scale at only 138 pounds. So, putting on weight became his goal. He started on a diet heavy with steaks, pasta, and milkshakes. When he stepped on the scales at his second physical in March of 1941, he was still a little shy of the minimum weight, but someone fudged the figures by a few ounces, and Jimmy Stewart was on his way to boot camp.

Eager as he was to serve, it was a bit of an adjustment. He’d been averaging $12,000 a week as an actor, according to the article “Mr. Stewart Goes to War,” by Richard L. Hayes on the HistoryNet website. An army private’s pay was $21 a month. It is reported that he sent $2.10 a month to his agent.

Stewart had a college degree from Princeton, and he was already licensed to fly multi-engine planes, so it was no surprise when he got his commission in January 1942. That meant he could wear his uniform when he presented Gary Cooper the Academy Award for best actor for Cooper’s performance in Sergeant York. Stewart had won the Oscar the year before for his role in Philadelphia Story.

The actor became a flight instructor, serving first at Mather Field, California, then transferred to Kirkland, New Mexico for bombardier school. He was at another base in New Mexico and HQ for the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City before coming to Boise, where he was a flight instructor for B-17s. He was also a sensation.

The About Town column on February 21, 1943, read, “Being constantly on the lookout for Jimmy Stewart has made Boiseans celebrity-conscious. We could have sworn we’ve been seeing Lucille Ball and John Garfield night-spotting about town…but it turned out to be Eileen Cummock, beauteous Gowen Field civilian employee, and Capt. Cox.”

About Town was breathless with chatter about Stewart. It wasn’t until June 21 that the paper published an actual photograph of the “ordinary American serving his country.” He was shown visiting back stage at a Gowen Field minstrel show at the Pinney Theater. They published another six days later of Stewart shaking hands with someone at a “recent Gowen Field Frolic.”

In July that year, Stewart got his captain’s bars and was called back to Hollywood to attend a wedding. In August, his stint in Boise was over. His stint in the military had just begun.

Jimmy Stewart would fly 20 bombing missions over Europe in World War II. Those were the missions he was credited with. He often flew self-assigned as a combat crewman when he was a commander. Oddly, he flew on one bombing mission in Vietnam as a non-duty observer in a B-52 when he was Air Force Reserve Brigadier General Stewart in 1966. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. In 1985, President Reagan promoted him to Major General on the retired list and presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Stewart didn’t spend a lot of time talking about the war or his military service. In fact, his movie contracts always included a clause that his military service would not be used as part of the publicity for the movie. Stewart passed away in 1997.

#idahohistory #jimmystewart #gowenfield #boisehistory

On page one of the same edition, the story read, “He’s Jimmy Stewart to millions of movie fans, but at Gowen Field Saturday he registered as First Lt. James M. Stewart, and on the routine registration forms, in the listing his occupation in civilian life he placed a question mark after the word ‘actor.’”

Stewart had been determined to serve his country. When he tried to enlist in the army, they turned him down because he was too skinny. At 6-foot-3, he tipped the scale at only 138 pounds. So, putting on weight became his goal. He started on a diet heavy with steaks, pasta, and milkshakes. When he stepped on the scales at his second physical in March of 1941, he was still a little shy of the minimum weight, but someone fudged the figures by a few ounces, and Jimmy Stewart was on his way to boot camp.

Eager as he was to serve, it was a bit of an adjustment. He’d been averaging $12,000 a week as an actor, according to the article “Mr. Stewart Goes to War,” by Richard L. Hayes on the HistoryNet website. An army private’s pay was $21 a month. It is reported that he sent $2.10 a month to his agent.

Stewart had a college degree from Princeton, and he was already licensed to fly multi-engine planes, so it was no surprise when he got his commission in January 1942. That meant he could wear his uniform when he presented Gary Cooper the Academy Award for best actor for Cooper’s performance in Sergeant York. Stewart had won the Oscar the year before for his role in Philadelphia Story.

The actor became a flight instructor, serving first at Mather Field, California, then transferred to Kirkland, New Mexico for bombardier school. He was at another base in New Mexico and HQ for the Second Air Force in Salt Lake City before coming to Boise, where he was a flight instructor for B-17s. He was also a sensation.

The About Town column on February 21, 1943, read, “Being constantly on the lookout for Jimmy Stewart has made Boiseans celebrity-conscious. We could have sworn we’ve been seeing Lucille Ball and John Garfield night-spotting about town…but it turned out to be Eileen Cummock, beauteous Gowen Field civilian employee, and Capt. Cox.”

About Town was breathless with chatter about Stewart. It wasn’t until June 21 that the paper published an actual photograph of the “ordinary American serving his country.” He was shown visiting back stage at a Gowen Field minstrel show at the Pinney Theater. They published another six days later of Stewart shaking hands with someone at a “recent Gowen Field Frolic.”

In July that year, Stewart got his captain’s bars and was called back to Hollywood to attend a wedding. In August, his stint in Boise was over. His stint in the military had just begun.

Jimmy Stewart would fly 20 bombing missions over Europe in World War II. Those were the missions he was credited with. He often flew self-assigned as a combat crewman when he was a commander. Oddly, he flew on one bombing mission in Vietnam as a non-duty observer in a B-52 when he was Air Force Reserve Brigadier General Stewart in 1966. He retired from the Air Force in 1968. In 1985, President Reagan promoted him to Major General on the retired list and presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Stewart didn’t spend a lot of time talking about the war or his military service. In fact, his movie contracts always included a clause that his military service would not be used as part of the publicity for the movie. Stewart passed away in 1997.

#idahohistory #jimmystewart #gowenfield #boisehistory

Published on January 28, 2019 04:00

January 27, 2019

Build it. Fast!

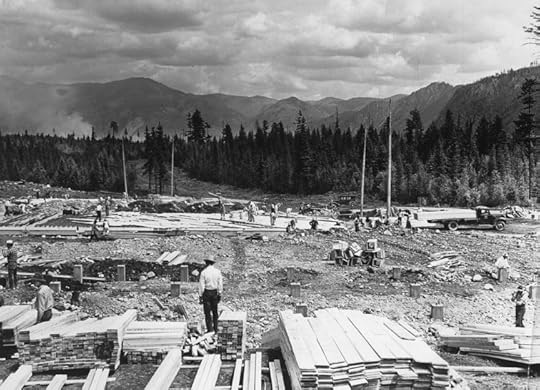

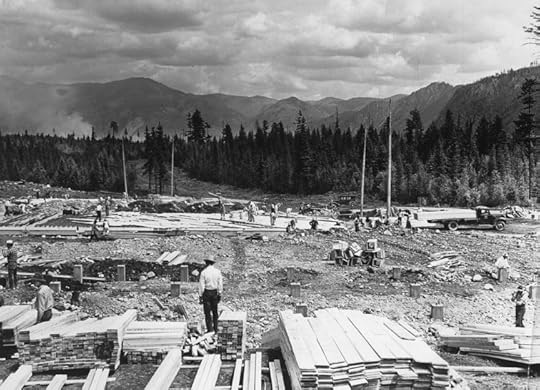

The next time you feel like grumbling about that road project that seems to go on forever, remember Farragut State Park. More appropriately, remember the Farragut Naval Training Station that was built on the shores of Lake Pend Oreille to train Navy recruits for World War II.

Building an all new naval training station was a tremendous effort. It had to be done fast, because the war was suddenly on. This photograph shows construction at Camp Waldron barracks in 1942. Construction at Farragut Naval Training Station began in March, and recruits started training in September of THE SAME YEAR. The final construction budget was $57 million. Recruits, called “boots,” would train there for only 26 months. Even so, 293,380 men received their basic training at Farragut.

Today, Farragut State Park remembers those naval training station days with a series of exhibits in the original Navy brig.

#idahohistory #farragut #farragutstatepark #navalhistory #navyhistory

Building an all new naval training station was a tremendous effort. It had to be done fast, because the war was suddenly on. This photograph shows construction at Camp Waldron barracks in 1942. Construction at Farragut Naval Training Station began in March, and recruits started training in September of THE SAME YEAR. The final construction budget was $57 million. Recruits, called “boots,” would train there for only 26 months. Even so, 293,380 men received their basic training at Farragut.

Today, Farragut State Park remembers those naval training station days with a series of exhibits in the original Navy brig.

#idahohistory #farragut #farragutstatepark #navalhistory #navyhistory

Published on January 27, 2019 04:00

January 26, 2019

An Early Counterfeiting Scheme

A typical little family portrait caught my eye when perusing photos at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. It wasn’t so much the photo, but the neatly written note on the cardstock where it was mounted. It said “Eddy, John and family. He made counterfeit 25¢ pieces at Little Salmon.”

Why, I wondered, would it be worth risking prison to make counterfeit quarters? Sure, two bits was worth more in 1897, but was it worth enough to risk making little rocks out big ones in Idaho’s penitentiary?

No, it wasn’t. I did a newspaper search for Mr. Eddy and found that he was arrested for counterfeiting in 1897, but quarters didn’t come into play. Someone had simply written the wrong symbol next to the photo. Oh, and the wrong number. It was $5, $10, and $20 gold pieces Eddy and his accomplices were counterfeiting.

As if counterfeiting weren’t bad enough, the gang gave their whole operation a reprehensible twist. To make the coins they would sometimes use silver and sometimes use cheaper babbitt metal (composed of tin, antimony, lead, and copper), heating it up and pouring the melted metal into molds. Then, they put a thin coat of gold over the coin. Once they had a supply, they would target Nez Perce Indians, trading their phony coins for bills the Indians received in government payments. The Nez Perce preferred the jingle of coins to paper money. The gang got away with it for a while, but Deputy U.S. Marshall Mounce, working out of Grangeville, hired a detective to infiltrate the gang. They were caught getting ready to pull off a scheme where they were to race a horse at an Indian meet and change their winnings from greenbacks to funny money.

John Eddy, his brother Lewis, and five other men were convicted of counterfeiting and each was sentenced for up to 16 years in prison. They were called by one newspaper “the most successful gang of counterfeiters that ever operated in the northwest.” I would probably hesitate to assign the word “successful” to people who went to prison, but that’s just me.

#idahohistory #counterfeiting #grangevilleidaho

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Why, I wondered, would it be worth risking prison to make counterfeit quarters? Sure, two bits was worth more in 1897, but was it worth enough to risk making little rocks out big ones in Idaho’s penitentiary?

No, it wasn’t. I did a newspaper search for Mr. Eddy and found that he was arrested for counterfeiting in 1897, but quarters didn’t come into play. Someone had simply written the wrong symbol next to the photo. Oh, and the wrong number. It was $5, $10, and $20 gold pieces Eddy and his accomplices were counterfeiting.

As if counterfeiting weren’t bad enough, the gang gave their whole operation a reprehensible twist. To make the coins they would sometimes use silver and sometimes use cheaper babbitt metal (composed of tin, antimony, lead, and copper), heating it up and pouring the melted metal into molds. Then, they put a thin coat of gold over the coin. Once they had a supply, they would target Nez Perce Indians, trading their phony coins for bills the Indians received in government payments. The Nez Perce preferred the jingle of coins to paper money. The gang got away with it for a while, but Deputy U.S. Marshall Mounce, working out of Grangeville, hired a detective to infiltrate the gang. They were caught getting ready to pull off a scheme where they were to race a horse at an Indian meet and change their winnings from greenbacks to funny money.

John Eddy, his brother Lewis, and five other men were convicted of counterfeiting and each was sentenced for up to 16 years in prison. They were called by one newspaper “the most successful gang of counterfeiters that ever operated in the northwest.” I would probably hesitate to assign the word “successful” to people who went to prison, but that’s just me.

#idahohistory #counterfeiting #grangevilleidaho

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Convicted counterfeiter John Eddy, his family, and part of a dog. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s physical photo collection.

Published on January 26, 2019 04:00

January 25, 2019

Elliot Richardson in Idaho

The Railroad Ranch, which would become Harriman State Park, had many well-known visitors over the years. This was late in the history of the ranch. On the left is Steve Bly, who was the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation director in 1974 when the picture was taken. The fish belongs to Elliot Richardson. He was US attorney general during the Nixon and Ford Administration. He famously resigned rather than fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox on Nixon’s order during the Watergate scandal.

Former Idaho Congressman Walt Minnick, who at the time was serving in the Nixon administration, also resigned in protest.

By the way, fishing is no longer allowed in Silver and Golden lakes within the park. You can fish in Millionaires Hole on the Henrys Fork as it winds in front of the ranch compound. You can’t keep those trophy trout, though. It’s catch and release only.

#idahohistory #elliotrichardson #harrimanstatepark #stevebly #henrysfork #waltminnick

Former Idaho Congressman Walt Minnick, who at the time was serving in the Nixon administration, also resigned in protest.

By the way, fishing is no longer allowed in Silver and Golden lakes within the park. You can fish in Millionaires Hole on the Henrys Fork as it winds in front of the ranch compound. You can’t keep those trophy trout, though. It’s catch and release only.

#idahohistory #elliotrichardson #harrimanstatepark #stevebly #henrysfork #waltminnick

Published on January 25, 2019 04:00

January 24, 2019

The Nevada Land Grab

In the early days of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho territories boundaries bounced around a bit until they settled on the shapes you know today. I was surprised to see an article in the January 25, 1870 Idaho Statesman about an attempt to bite off a good chunk of Idaho by our neighbors to the south (see image).

The article began, “We publish today a copy of a bill introduced into the United States senate by Senator Stewart of Nevada to annex the county of Owyhee and a large part of Oneida to that state.”

If the bill had passed, it likely would have led to a land grab by Oregon and Washington to annex other parts of the seven-year-old Idaho Territory. It perturbed the Statesman that the bill did not even mention the word Idaho. As the article stated, “The bill so reads that the people of Nevada are the only parties to be consulted. To the people of Idaho there is not so much as a ‘by your leave’ not even to the people of Owyhee county who are to be thus raffled off for the benefit of bankrupt Nevada.”

The Statesman didn’t take the effort very seriously, and neither did Congress. The next time the bill was mentioned in the paper was 50 years later as a footnote in the 50 Years Ago column.

#idahohistory #nevadahistory

The article began, “We publish today a copy of a bill introduced into the United States senate by Senator Stewart of Nevada to annex the county of Owyhee and a large part of Oneida to that state.”

If the bill had passed, it likely would have led to a land grab by Oregon and Washington to annex other parts of the seven-year-old Idaho Territory. It perturbed the Statesman that the bill did not even mention the word Idaho. As the article stated, “The bill so reads that the people of Nevada are the only parties to be consulted. To the people of Idaho there is not so much as a ‘by your leave’ not even to the people of Owyhee county who are to be thus raffled off for the benefit of bankrupt Nevada.”

The Statesman didn’t take the effort very seriously, and neither did Congress. The next time the bill was mentioned in the paper was 50 years later as a footnote in the 50 Years Ago column.

#idahohistory #nevadahistory

Published on January 24, 2019 04:00

January 23, 2019

What's Your Number?

Time for another then and now feature.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan, but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

#idahohistory #idahoareacode

I know, this looks like one of those fake numbers you see in advertising. It's not. It's the non-emergency number for the Blackfoot police department. Leave them alone, please.

I know, this looks like one of those fake numbers you see in advertising. It's not. It's the non-emergency number for the Blackfoot police department. Leave them alone, please.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan, but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

#idahohistory #idahoareacode

I know, this looks like one of those fake numbers you see in advertising. It's not. It's the non-emergency number for the Blackfoot police department. Leave them alone, please.

I know, this looks like one of those fake numbers you see in advertising. It's not. It's the non-emergency number for the Blackfoot police department. Leave them alone, please.

Published on January 23, 2019 04:00

January 22, 2019

Wardner, Idaho and its Namesake

Yes, this is the story about that famous jackass that found the Bunker Hill Mine, but it’s also about an entrepreneur named Jim Wardner, who found a clever way to take advantage of that discovery.

Wardner, by his own account, was a man always on the lookout for whatever would make him rich. With that goal in mind he spent some time as an assistant tapeworm remover, the owner of the exclusive rights to an anti-cow-kicking milking stool in the entire state of Wisconsin, a failed investor in hogs, the exhibitor of a “wild man,” the owner of a saloon and store in Deadwood where he claimed to be the first to sell oysters to gourmand miners, a freighter with 500 yoke of oxen, a gambler who once won a few thousand on a walking contest, and the distributor of butterine (a butter substitute), some of which he personally hauled into Idaho mining camps by pulling a toboggan.

Wardner had done pretty well in the Coeur d’Alene mining district with his various enterprises and was all packed up to go back to Wisconsin to his long-suffering wife, ready to give up his dreams of riches, when an acquaintance he’d grubstaked a bit came galloping into town. Upon seeing Wardner he said he could now pay him back for his past kindness because he and some other men had found one hell of a vein.

Never one to let news of a rich find slide by, Wardner set out that evening to find the mining camp. He came upon it just at sunrise. The three men sitting around the fire knew Wardner and when they saw that he had brought whiskey welcomed him into the camp. As the sun cleared the mountain tops a flash from across the canyon could not be missed. It was sunshine reflecting off a long, exposed vein of galena.

Noah Kellogg told Wardner the now famous story about how his jackass had gotten loose and led the men on a chase through the woods and across downed timber for quite some time until they saw the beast standing still and looking across the canyon as if something had caught his eye. That something was the flash of galena Wardner had now seen. The jackass would forever get credit for the discovery of the Bunker Hill Mine. A refrain from an old concert hall jingle from the time went like this:

“When you talk about the Coeur d’Alenes

And all their wealth untold,

Don’t fail to mention ‘Kellogg’s Jack,’

Who did that wealth unfold!”

Wardner, perhaps the first to hear that story, began thinking of a way to get in on this fabulous find. He told the men he thought he’d take a little stroll and asked if he could borrow an axe in case he needed to blaze a trail. He blazed, instead, a spot in a tree alongside what would later be called Milo Creek and wrote his claim to water rights in the stream in pencil on the blaze. Then he went back to the miners and asked them to come along with him. When they got to the tree, he asked them to witness his claim to water rights.

Men who had not just found wealth beyond their wildest dreams might have simply drowned him on the spot, but they played fair with Wardner and signed as witnesses, knowing that water rights were absolutely essential in mining and kicking themselves for not thinking of that sooner.

Wardner then agreed to put up a considerable sum—more than $15,000—to get the operation going. He bought up some lots in a nearby town which would end up being called Wardner. Eventually he would sell his water rights and mine shares in the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines, and strike out for other adventures. Chasing gold would take him to the Klondike, South Africa, and British Columbia. There’s another small town named Wardner in British Columbia, named after you know who.

Jim Wardner went on to make and lose fortunes, even trying his hand at raising cats for their fur for a time on an island in Puget Sound. He died in El Paso, Texas in 1905.

Image: Wardner, Idaho, in 1886. The animal in the foreground with kids astride it is the “4 million dollar” jackass that found the galena that would become the Bunker Hill Mine. The star in the upper right of the photo is the location of the mine. The photo comes from the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho published in 1900, which is an excellent read.

Thanks to Tim Blood who led me to the Wardner book.

#idahohistory #wardneridaho #kelloggidaho #mining

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Wardner, by his own account, was a man always on the lookout for whatever would make him rich. With that goal in mind he spent some time as an assistant tapeworm remover, the owner of the exclusive rights to an anti-cow-kicking milking stool in the entire state of Wisconsin, a failed investor in hogs, the exhibitor of a “wild man,” the owner of a saloon and store in Deadwood where he claimed to be the first to sell oysters to gourmand miners, a freighter with 500 yoke of oxen, a gambler who once won a few thousand on a walking contest, and the distributor of butterine (a butter substitute), some of which he personally hauled into Idaho mining camps by pulling a toboggan.

Wardner had done pretty well in the Coeur d’Alene mining district with his various enterprises and was all packed up to go back to Wisconsin to his long-suffering wife, ready to give up his dreams of riches, when an acquaintance he’d grubstaked a bit came galloping into town. Upon seeing Wardner he said he could now pay him back for his past kindness because he and some other men had found one hell of a vein.

Never one to let news of a rich find slide by, Wardner set out that evening to find the mining camp. He came upon it just at sunrise. The three men sitting around the fire knew Wardner and when they saw that he had brought whiskey welcomed him into the camp. As the sun cleared the mountain tops a flash from across the canyon could not be missed. It was sunshine reflecting off a long, exposed vein of galena.

Noah Kellogg told Wardner the now famous story about how his jackass had gotten loose and led the men on a chase through the woods and across downed timber for quite some time until they saw the beast standing still and looking across the canyon as if something had caught his eye. That something was the flash of galena Wardner had now seen. The jackass would forever get credit for the discovery of the Bunker Hill Mine. A refrain from an old concert hall jingle from the time went like this:

“When you talk about the Coeur d’Alenes

And all their wealth untold,

Don’t fail to mention ‘Kellogg’s Jack,’

Who did that wealth unfold!”

Wardner, perhaps the first to hear that story, began thinking of a way to get in on this fabulous find. He told the men he thought he’d take a little stroll and asked if he could borrow an axe in case he needed to blaze a trail. He blazed, instead, a spot in a tree alongside what would later be called Milo Creek and wrote his claim to water rights in the stream in pencil on the blaze. Then he went back to the miners and asked them to come along with him. When they got to the tree, he asked them to witness his claim to water rights.

Men who had not just found wealth beyond their wildest dreams might have simply drowned him on the spot, but they played fair with Wardner and signed as witnesses, knowing that water rights were absolutely essential in mining and kicking themselves for not thinking of that sooner.

Wardner then agreed to put up a considerable sum—more than $15,000—to get the operation going. He bought up some lots in a nearby town which would end up being called Wardner. Eventually he would sell his water rights and mine shares in the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mines, and strike out for other adventures. Chasing gold would take him to the Klondike, South Africa, and British Columbia. There’s another small town named Wardner in British Columbia, named after you know who.

Jim Wardner went on to make and lose fortunes, even trying his hand at raising cats for their fur for a time on an island in Puget Sound. He died in El Paso, Texas in 1905.

Image: Wardner, Idaho, in 1886. The animal in the foreground with kids astride it is the “4 million dollar” jackass that found the galena that would become the Bunker Hill Mine. The star in the upper right of the photo is the location of the mine. The photo comes from the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho published in 1900, which is an excellent read.

Thanks to Tim Blood who led me to the Wardner book.

#idahohistory #wardneridaho #kelloggidaho #mining

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Wardner, Idaho in 1886. The $4 million jackass in the foreground. The star marks the site of the Bunker Hill Mine. From the book Jim Wardner, of Wardner Idaho.

Published on January 22, 2019 04:00

January 21, 2019

Birds of a Feather, Not

Here's a link to my latest Idaho Press column.

Published on January 21, 2019 04:14

January 20, 2019

The North Side Inn

In 1910 a lavish, modern hotel could be found standing in the middle of the southern Idaho desert near where the town of Jerome is today. Actually, it is exactly where the town of Jerome is, because the hotel had been built as a way to create Jerome and sell tracts of land newly opened for farming.

Jerome Kuhn and his brother W. H. were developers from Pittsburgh who had created the North Side Land and Water Company and the South Side Land and Water Company. The former was on the north side of the Snake River and the latter to the south. The millionaire brothers were exploiting the new Milner Dam which would bring water to the thirsty desert through a system of canals.

Why start with a fancy hotel? Because the potential buyers of said property would need a place to stay while examining the land.

Jerome Kuhn left his name on the town of Jerome and the county with the same name. Possibly. There is considerable confusion about that. It might have been named for Jerome Kuhn, Sr, Jerome Kuhn, Jr, or for Jerome Hill, a prominent investor in the projects. Wendell, Idaho, meanwhile, was named after the son of W.H. Kuhn. Unless his initials were W.S., of course. I’ve seen it both ways.

But the hotel.

The North Side Inn was a landmark in Jerome for 58 years before being torn down in 1968. It was much loved, and many residents hated to see it go. Some loved it so much that they built a replica of the hotel in 2009. It was meant to function as an office building but wasn’t immediately successful in the economic downturn taking place at the time. Called Heritage Plaza, the 14,000 sq ft building resembles the North Side Inn on the exterior, but with less detail. It was still available for sale or lease as this was written.

#idahohistory #jeromeidaho #jeromeidahohistory #northsideinn The North Side Inn.

The North Side Inn.  The North Side Heritage Plaza.

The North Side Heritage Plaza.

Jerome Kuhn and his brother W. H. were developers from Pittsburgh who had created the North Side Land and Water Company and the South Side Land and Water Company. The former was on the north side of the Snake River and the latter to the south. The millionaire brothers were exploiting the new Milner Dam which would bring water to the thirsty desert through a system of canals.

Why start with a fancy hotel? Because the potential buyers of said property would need a place to stay while examining the land.

Jerome Kuhn left his name on the town of Jerome and the county with the same name. Possibly. There is considerable confusion about that. It might have been named for Jerome Kuhn, Sr, Jerome Kuhn, Jr, or for Jerome Hill, a prominent investor in the projects. Wendell, Idaho, meanwhile, was named after the son of W.H. Kuhn. Unless his initials were W.S., of course. I’ve seen it both ways.

But the hotel.

The North Side Inn was a landmark in Jerome for 58 years before being torn down in 1968. It was much loved, and many residents hated to see it go. Some loved it so much that they built a replica of the hotel in 2009. It was meant to function as an office building but wasn’t immediately successful in the economic downturn taking place at the time. Called Heritage Plaza, the 14,000 sq ft building resembles the North Side Inn on the exterior, but with less detail. It was still available for sale or lease as this was written.

#idahohistory #jeromeidaho #jeromeidahohistory #northsideinn

The North Side Inn.

The North Side Inn.  The North Side Heritage Plaza.

The North Side Heritage Plaza.

Published on January 20, 2019 04:00