Rick Just's Blog, page 211

January 8, 2019

A Terrible Review

In these days of Yelp reviews and Air BnB, we’re quite used to seeing personal ratings of overnight accommodations. It wasn’t so common in 1874 when

The Mormon Country, A Summer with the “Latter Day Saints

,” written by John Codman was published.

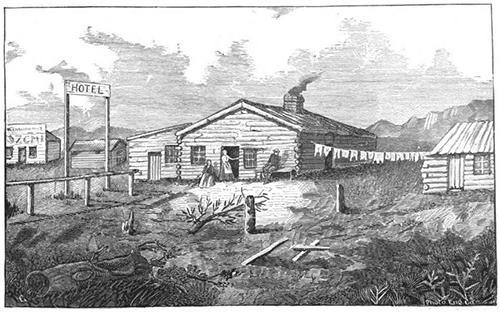

Codman lauded the mineral springs in Soda Springs and predicted that they would one day “infallibly make it a place of great resort.” His review of the Hotel Sterrit, though, would decidedly get a single star nowadays.

“Some ‘hotels’ I have seen in the wilds of Africa, the plains of India, the slums of Constantinople; but the ‘Hotel Sterrit’ of Soda Springs is the meanest building of that description into which I ever crept.” He went a step further by insulting the proprietor, to wit, “Sterrit(‘s)… energies seem to be directed to raising a numerous family, and making his boarders pay for it by getting nothing in return for their money.”

There being a single game in town of the hotel variety, Codman spent a fortnight in the Sterrit. He grumped that “I know that I can attribute my health to the waters, for food, of which there was none, could have had nothing to do with it.”

Codman hastened to report that a new and comparatively comfortable hotel was to be completed the next spring. What he didn’t know was that in 1887 a truly luxurious and beautiful hotel would be built in Soda Springs, the original Idanha, fulfilling his resort prophesy.

#idahohistory #sodasprings #sterrit

Codman lauded the mineral springs in Soda Springs and predicted that they would one day “infallibly make it a place of great resort.” His review of the Hotel Sterrit, though, would decidedly get a single star nowadays.

“Some ‘hotels’ I have seen in the wilds of Africa, the plains of India, the slums of Constantinople; but the ‘Hotel Sterrit’ of Soda Springs is the meanest building of that description into which I ever crept.” He went a step further by insulting the proprietor, to wit, “Sterrit(‘s)… energies seem to be directed to raising a numerous family, and making his boarders pay for it by getting nothing in return for their money.”

There being a single game in town of the hotel variety, Codman spent a fortnight in the Sterrit. He grumped that “I know that I can attribute my health to the waters, for food, of which there was none, could have had nothing to do with it.”

Codman hastened to report that a new and comparatively comfortable hotel was to be completed the next spring. What he didn’t know was that in 1887 a truly luxurious and beautiful hotel would be built in Soda Springs, the original Idanha, fulfilling his resort prophesy.

#idahohistory #sodasprings #sterrit

Published on January 08, 2019 04:00

January 7, 2019

Message in a Bottle

In the fall of 1893, W.E. Carlin, the son of Brig. Gen. W.P. Carlin, Commander of the department of the Columbia, Vancouver, Washington, gathered together some friends for a hunting party in the Bitterroots of Idaho. They hired a Post Falls woodsman named George Colgate to cook for their little expedition.

A.L.A. Himmelwright, a businessman from New York who was on the trip, would later write a book about it. The details he provided painted a picture of a well-outfitted expedition: 125 pounds of flour, 30 pounds of bacon, 40 pounds of salt pork, 20 pounds of beans, eight pounds of coffee, and on and on. He described the guns, including Carlin’s three-barreled weapon that had two 12-gauge shotgun bores side-by-side with a .32 rifle beneath.

The group got to Kendrick by train, where they gathered together the supplies, five saddle horses, five pack horses, a spaniel and two terriers, and set out for a hunt.

Six inches of snow fell on September 22. That concerned guide Martin Spencer. He figured it would only get deeper as they moved higher into the mountains. Carlin decided to push on despite the snow, and although their cook had become ill. George Colgate’s legs had swollen to the point where he could barely hobble around. Everyone else shared in cooking duties as his abilities waned.

In the days to come Colgate rallied, then got progressively worse. One day he couldn’t even stay on his horse. As more snow flew, members of the hunting party nursed the cook while he lay in a tent.

Fifty miles from anything like civilization the Carlin party found themselves in a desperate situation with snow blocking trails and a man who could not be moved on their hands. Colgate was so sick he couldn’t talk. The men debated what to do. Should they stick it out where they were and hope the weather would break? Should they send someone ahead to bring back a rescue party?

While they pondered, another storm struck. Food was running short. They had to get out of there.

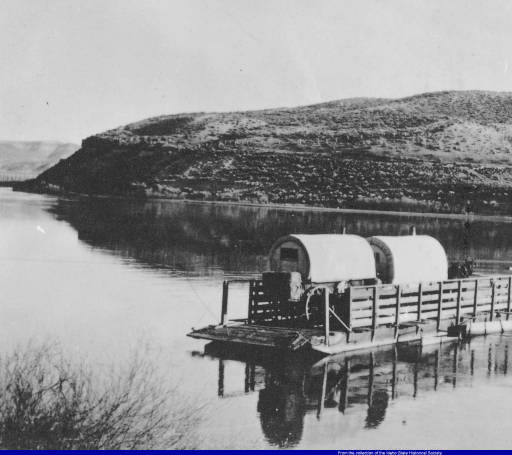

Someone struck on the idea of building a raft to float down the Lochsa. They lashed together some logs with cord and wire and attached a long sweep with which to guide the contraption. Before setting out on the raft, Himmelwright would make a dark entry in his diary: “It is a case of trying to save five lives or sacrificing them to perform the last sad rites for Colgate.”

The men set out downriver, leaving their cook behind seemingly on death’s door.

Cutting the story short, the hunting party lost their raft in a rapid several miles downstream. They survived by shooting a few grouse, catching a few fish, and even eating one of their dogs before a rescue party found them on November 21.

And now the story gets strange.

The men of the party were well known, so the tale of their failure to return when expected and their ultimate rescue had been carried in many newspapers, including the New York Times, which also carried the story of the bottle.

What bottle? The one that was purportedly found in the Snake River by one Sam Ellis at Penewawi, some 60 miles below Lewiston. Inside the bottle was this note:

FOOT OF BITTER ROOT MOUNTAINS, Nov. 27.—I am alive and well. Tell them to come and get me as soon as any one finds this. I am 50 miles from civilization as near as I can tell. I am George Colgate, one of the lost Carlin party. My legs are better. I can walk some. Come soon. Take this to Kendrick, Idaho, and you will be liberally rewarded. My name is George Colgate, from Post Falls. This bottle came by me and I caught it and wrote these words to take me out. Direct this to St. Elmo hotel, Kendrick, Idaho.

GEORGE COLGATE

“Good bye, wife and children.”

The small bottle was corked and fastened to a piece of driftwood with a rag tied to it.

The writing on the note was compared to Colgate’s signature on a hotel register and “was found to be wonderfully close.”

Two relief parties set out to rescue Colgate in the coming months. Neither met with success. Meanwhile, Carlin was adamant that the note in the bottle was a fake designed to somehow extort money from him and ruin his reputation.

The note seems a little pat and the finding of the bottle incredible, so maybe Carlin was right. In any case, his reputation suffered. There was debate for decades about the ethics of leaving a man to die in the wilderness.

And die he did. On August 23, 1894, the remains of George Colgate were found about eight miles from the spot where he was said to have been abandoned. How did he get there along with a matchbox, some fishing line, and other personal articles? Had he rallied long enough to drag himself through the snow that far? Had he lived to write a message in a bottle?

#idahohistory #georgecolgate

A.L.A. Himmelwright, a businessman from New York who was on the trip, would later write a book about it. The details he provided painted a picture of a well-outfitted expedition: 125 pounds of flour, 30 pounds of bacon, 40 pounds of salt pork, 20 pounds of beans, eight pounds of coffee, and on and on. He described the guns, including Carlin’s three-barreled weapon that had two 12-gauge shotgun bores side-by-side with a .32 rifle beneath.

The group got to Kendrick by train, where they gathered together the supplies, five saddle horses, five pack horses, a spaniel and two terriers, and set out for a hunt.

Six inches of snow fell on September 22. That concerned guide Martin Spencer. He figured it would only get deeper as they moved higher into the mountains. Carlin decided to push on despite the snow, and although their cook had become ill. George Colgate’s legs had swollen to the point where he could barely hobble around. Everyone else shared in cooking duties as his abilities waned.

In the days to come Colgate rallied, then got progressively worse. One day he couldn’t even stay on his horse. As more snow flew, members of the hunting party nursed the cook while he lay in a tent.

Fifty miles from anything like civilization the Carlin party found themselves in a desperate situation with snow blocking trails and a man who could not be moved on their hands. Colgate was so sick he couldn’t talk. The men debated what to do. Should they stick it out where they were and hope the weather would break? Should they send someone ahead to bring back a rescue party?

While they pondered, another storm struck. Food was running short. They had to get out of there.

Someone struck on the idea of building a raft to float down the Lochsa. They lashed together some logs with cord and wire and attached a long sweep with which to guide the contraption. Before setting out on the raft, Himmelwright would make a dark entry in his diary: “It is a case of trying to save five lives or sacrificing them to perform the last sad rites for Colgate.”

The men set out downriver, leaving their cook behind seemingly on death’s door.

Cutting the story short, the hunting party lost their raft in a rapid several miles downstream. They survived by shooting a few grouse, catching a few fish, and even eating one of their dogs before a rescue party found them on November 21.

And now the story gets strange.

The men of the party were well known, so the tale of their failure to return when expected and their ultimate rescue had been carried in many newspapers, including the New York Times, which also carried the story of the bottle.

What bottle? The one that was purportedly found in the Snake River by one Sam Ellis at Penewawi, some 60 miles below Lewiston. Inside the bottle was this note:

FOOT OF BITTER ROOT MOUNTAINS, Nov. 27.—I am alive and well. Tell them to come and get me as soon as any one finds this. I am 50 miles from civilization as near as I can tell. I am George Colgate, one of the lost Carlin party. My legs are better. I can walk some. Come soon. Take this to Kendrick, Idaho, and you will be liberally rewarded. My name is George Colgate, from Post Falls. This bottle came by me and I caught it and wrote these words to take me out. Direct this to St. Elmo hotel, Kendrick, Idaho.

GEORGE COLGATE

“Good bye, wife and children.”

The small bottle was corked and fastened to a piece of driftwood with a rag tied to it.

The writing on the note was compared to Colgate’s signature on a hotel register and “was found to be wonderfully close.”

Two relief parties set out to rescue Colgate in the coming months. Neither met with success. Meanwhile, Carlin was adamant that the note in the bottle was a fake designed to somehow extort money from him and ruin his reputation.

The note seems a little pat and the finding of the bottle incredible, so maybe Carlin was right. In any case, his reputation suffered. There was debate for decades about the ethics of leaving a man to die in the wilderness.

And die he did. On August 23, 1894, the remains of George Colgate were found about eight miles from the spot where he was said to have been abandoned. How did he get there along with a matchbox, some fishing line, and other personal articles? Had he rallied long enough to drag himself through the snow that far? Had he lived to write a message in a bottle?

#idahohistory #georgecolgate

Published on January 07, 2019 04:00

January 6, 2019

The Governor did not like that Song

Rosalie Sorrels, who passed away in 2017, was a much beloved Idaho folksinger and storyteller. Not universally beloved, however. Governor Don Samuelson was one who didn’t care for her or her lyrics.

Folk music has a long, proud history of political involvement and Rosalie never shied from a cause she believed in. In 1970 the cause was saving the White Clouds from a proposed open pit molybdenum mine at the base of Castle Peak. The song, “White Clouds,” was not meant as a particular poke in the eye for Governor Samuelson, though he took it that way. It was a poetic appeal to save wilderness from commercial encroachment and pollution. And it wasn’t so much that the governor was annoyed by Rosalie’s song as he was by the fact that a state employee was singing it. Stacy Gebhards was the Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s fishery management supervisor in 1970.

Gebhards performed “White Clouds” at several events rallying support to save the mountain from development. He and a couple of friends also performed it at a state dinner at which Interior Secretary Walter G. Hickel was in attendance. Governor Samuelson was there, too, and when the accompanying slide show started showing dramatic shots of pollution around the state, Samuelson began steaming.

Hickel later gave Gebhards a personal commendation and congratulatory letter. But word came from the governor’s office that if he ever sang the song in public again, Gebhards would be fired.

Paul Swenson, a writer for the Deseret News out of Salt Lake quoted an un-named source as saying, “The governor blew his stack.”

Gebhards kept his job. Rosalie Sorrels kept writing and singing. Samuelson lost the next election to Cecil D. Andrus, and Castle Peak remains pristine today.

Much of the information for this post came from Rosalie Sorrels’ book Way out in Idaho: A Celebration of Songs and Stories .

#idahohistory #stacygebhards #rosaliesorrels

Folk music has a long, proud history of political involvement and Rosalie never shied from a cause she believed in. In 1970 the cause was saving the White Clouds from a proposed open pit molybdenum mine at the base of Castle Peak. The song, “White Clouds,” was not meant as a particular poke in the eye for Governor Samuelson, though he took it that way. It was a poetic appeal to save wilderness from commercial encroachment and pollution. And it wasn’t so much that the governor was annoyed by Rosalie’s song as he was by the fact that a state employee was singing it. Stacy Gebhards was the Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s fishery management supervisor in 1970.

Gebhards performed “White Clouds” at several events rallying support to save the mountain from development. He and a couple of friends also performed it at a state dinner at which Interior Secretary Walter G. Hickel was in attendance. Governor Samuelson was there, too, and when the accompanying slide show started showing dramatic shots of pollution around the state, Samuelson began steaming.

Hickel later gave Gebhards a personal commendation and congratulatory letter. But word came from the governor’s office that if he ever sang the song in public again, Gebhards would be fired.

Paul Swenson, a writer for the Deseret News out of Salt Lake quoted an un-named source as saying, “The governor blew his stack.”

Gebhards kept his job. Rosalie Sorrels kept writing and singing. Samuelson lost the next election to Cecil D. Andrus, and Castle Peak remains pristine today.

Much of the information for this post came from Rosalie Sorrels’ book Way out in Idaho: A Celebration of Songs and Stories .

#idahohistory #stacygebhards #rosaliesorrels

Published on January 06, 2019 04:00

January 5, 2019

Ferries that no Longer Carry Apostrophes

Quick, which is easier to build a boat or a bridge? If you were in Idaho Territory in the early 1860s the answer was usually a boat. If the boat regularly crossed from one side of a river and back again, you’d call it a ferry. There were many such ferries in early Idaho, and they’ve left their mark in enduring place names: Bonners Ferry, Glenns Ferry, Walters Ferry, Smiths Ferry, Ferry Butte, Ferry Creek. Just kidding about that last one. It was named after Rudolph Ferry who had a homestead there.

Perhaps a good measure of the importance of something is how quickly government jumps in to regulate it. Idaho Territory was created in 1863 and by 1864 there was a statute on the books regulating ferries and toll bridges. You couldn’t operate one without a license and you were told how much you could charge.

According to Idaho Session Laws, 1864, the folks operating, say, the Eagle Rock Ferry above what would become Idaho Falls could charge the following:

For a man and a horse, .50 Page

For a horse and a carriage, $3.00

For a wagon and two horses, or two oxen, $4.00

For each additional pair of horses or cattle, $1.00

For each animal with a pack, .50

For loose animals, other than sheep or hogs, .25

For sheep and hogs, each, .15

Saying that it cost 50 cents for a man and a horse to cross doesn’t tell the whole story. A dollar then would buy a lot more than a dollar now. A dollar in 1865 would be worth the equivalent of $14.65 in today’s buying power.

Ferries in early Idaho were often tethered to a cable that stretched across the river from bank to bank. Maintenance on ferries was a headache, and they sometimes broke loose, or got rammed by floating logs. In the long run, a bridge is better, so ferries were often replaced by bridges either at the same site or at a better bridge site.

Ferries always belonged to someone, and often were named after that person. That’s obvious. What isn’t so easy to understand is why the town names linked to ferries don’t have possessive apostrophes. Much to the chagrin of English students everywhere the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, the authority on naming conventions, rarely allows apostrophes. Here’s how they explain that in their

“Apostrophes suggesting possession or association are discouraged within the body of a proper geographic name (Henrys Fork: not Henry’s Fork). The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists. Thus, we write “Jamestown” instead of “James’town” or even “Richardsons Creek” instead of “Richard’s son’s creek.” The whole name can be made possessive or associative with an apostrophe at the end as in “Rogers Point’s rocky shore.” Apostrophes may be used within the body of a geographic name to denote a missing letter (Lake O’ the Woods) or when they normally exist in a surname used as part of a geographic name (O’Malley Draw).”

Dandy. But back in the days when ferries were operating references to them usually used apostrophes, so writing today about Glenn’s Ferry or Glenns Ferry can be a judgement call. And you thought writing this blog was easy.

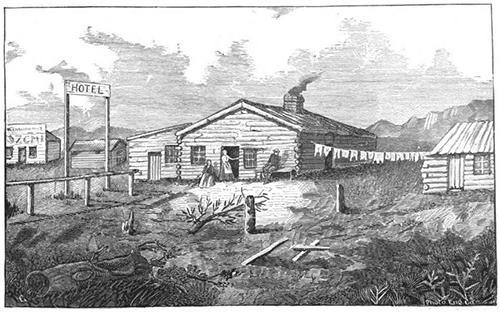

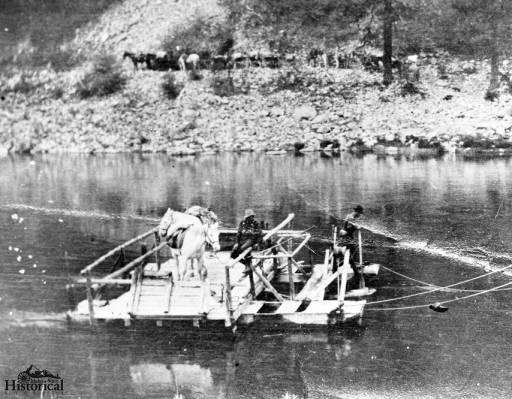

#idahohistory #ferry #geographicplacenames Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

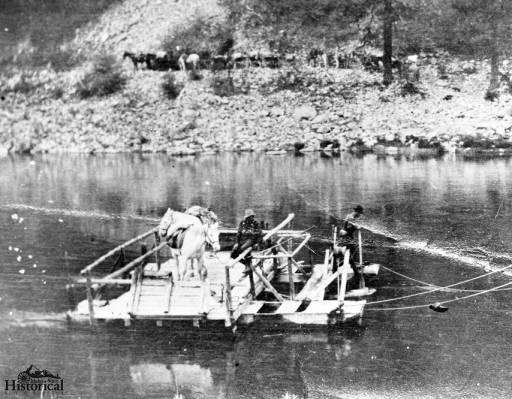

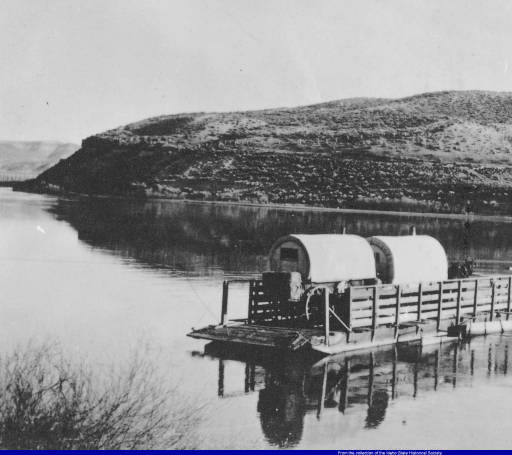

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

Perhaps a good measure of the importance of something is how quickly government jumps in to regulate it. Idaho Territory was created in 1863 and by 1864 there was a statute on the books regulating ferries and toll bridges. You couldn’t operate one without a license and you were told how much you could charge.

According to Idaho Session Laws, 1864, the folks operating, say, the Eagle Rock Ferry above what would become Idaho Falls could charge the following:

For a man and a horse, .50 Page

For a horse and a carriage, $3.00

For a wagon and two horses, or two oxen, $4.00

For each additional pair of horses or cattle, $1.00

For each animal with a pack, .50

For loose animals, other than sheep or hogs, .25

For sheep and hogs, each, .15

Saying that it cost 50 cents for a man and a horse to cross doesn’t tell the whole story. A dollar then would buy a lot more than a dollar now. A dollar in 1865 would be worth the equivalent of $14.65 in today’s buying power.

Ferries in early Idaho were often tethered to a cable that stretched across the river from bank to bank. Maintenance on ferries was a headache, and they sometimes broke loose, or got rammed by floating logs. In the long run, a bridge is better, so ferries were often replaced by bridges either at the same site or at a better bridge site.

Ferries always belonged to someone, and often were named after that person. That’s obvious. What isn’t so easy to understand is why the town names linked to ferries don’t have possessive apostrophes. Much to the chagrin of English students everywhere the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, the authority on naming conventions, rarely allows apostrophes. Here’s how they explain that in their

“Apostrophes suggesting possession or association are discouraged within the body of a proper geographic name (Henrys Fork: not Henry’s Fork). The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists. Thus, we write “Jamestown” instead of “James’town” or even “Richardsons Creek” instead of “Richard’s son’s creek.” The whole name can be made possessive or associative with an apostrophe at the end as in “Rogers Point’s rocky shore.” Apostrophes may be used within the body of a geographic name to denote a missing letter (Lake O’ the Woods) or when they normally exist in a surname used as part of a geographic name (O’Malley Draw).”

Dandy. But back in the days when ferries were operating references to them usually used apostrophes, so writing today about Glenn’s Ferry or Glenns Ferry can be a judgement call. And you thought writing this blog was easy.

#idahohistory #ferry #geographicplacenames

Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.  This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

Published on January 05, 2019 04:00

January 4, 2019

The Great Boise Autoist and Airplane Race of 1915

Barney Oldfield was easily the most famous autoist of his day. Yes, autoist. Newspapers had yet to settle on terms such as driver or racer or race car driver in 1902 when Oldfield switched from racing bicycles to racing cars. That happened when bike-racer Oldfield was in Salt Lake City and someone lent him a gasoline-powered bicycle to try out. Some would call that a motorcycle. Henry Ford saw him ride and asked him if he’d like to try a racing automobile. Yes. Yes, he would. Even though they couldn’t at first get the racing Ford to even start, Oldfield bought the machine and his racing career was on its way.

His first major win came about because he took the corners like a motorcycle racer, allowing the rear end of the car to slide out or fishtail around a curve. At the 1902 Manufacturer’s Challenge Cup, Oldfield beat the reigning champion by half a mile in a five-mile race using the technique.

Oldfield’s need for speed became famous, Newspapers loved to carry stories about his breaking a speed limit in some town or another. He was the first man to reach the startling speed of 60 miles per hour and the first to take a turn at the Indianapolis Speedway at over 100 mph. Police reportedly were fond of asking citizen speeders they picked up if they thought they were Barney Oldfield.

Common headlines across the country in the early part of the Twentieth Century were variations of “Oldfield Smashes Record” again and again. He didn’t confine his efforts to only racing. Oldfield was always up for a stunt. In 1910 he raced Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson, toying with the man on the track by surging ahead and falling back to let him catch up. In a wire service story, he said, “I raced Jack Johnson neither for money or glory, but to eliminate from my profession an invader who would have had to be reckoned with sooner or later.” He would have said that with his signature cigar poking from the corner of his mouth. He found early on that one driver looked much like another after a race, covered in dust or mud, but the one with a cigar in his mouth stood out.

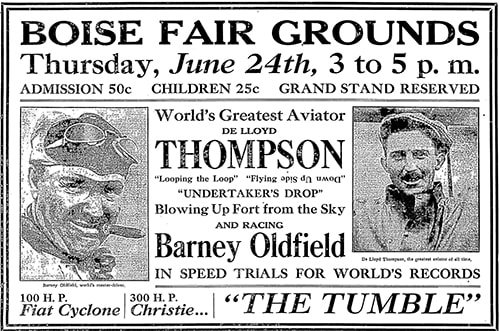

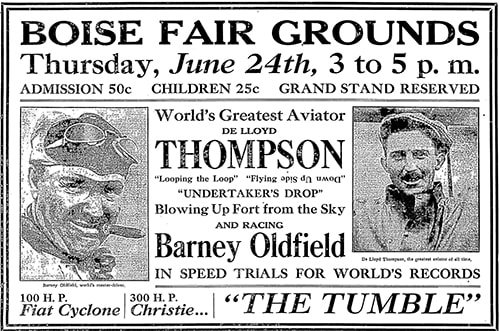

Oldfield became a sensation at county fairs all across the country. Prior to his appearance at the 1915 fairgrounds in Boise, The Idaho Statesman ran the following tease, “If neither Barney Oldfield, the world’s master driver, nor DeLoyd Thompson, the aerial marvel, is killed or injured when they present their series of sensational, spectacular and startling stunts on the massive Chicago speedway this afternoon, tonight they will commence their 1800-mile trip to appear in their nerve-tingling feats at the Boise race track on next Thursday afternoon.”

Boise Mayor Jeremiah W. Robinson climbed on board the hype train by declaring a “half holiday” the afternoon of June 24, the day of the exhibition of speed and daring. The Statesman piled on with “Thursday afternoon the clerks and other toilers, instead of simply visualizing the fear-chilling feats may, side by side with their employers, do what has been done in every other city where Thompson and Oldfield have shown—by their spontaneous and vociferous manifestations of appreciation demonstrate forcibly and indubitably that they coincide with the opinion of Mayor Robinson that each of these death cheaters is ‘without a peer in his line.’”

All the build-up worked. When the 24th rolled around the “largest crowd ever gathered in the city” turned out to see Oldfield and Thompson. There were 8,000 paid admissions.

Oldfield putted around the track in a couple of different cars, breaking the track record each time, for “the fastest mile ever traveled in Idaho,” according to the Statesman. Thompson, meanwhile, “soared aloft like a condor and tumbled to earth like a tumbler pigeon.”

Then the paper reported on the race with totally spontaneous and not at all scripted quotes. “The real excitement, with an accompaniment of comparative thrills, was produced by the race between Oldfield in his Flat Cyclone and Thompson in his biplane.

‘No cutting corners now,’ warned Barney as they got ready to start.

‘I don’t have to, to beat you in that old stinkpot, replied Thompson.

‘For mercy’s sake don’t fly too low this time,’ pleaded Mrs. Oldfield. “I look such a fright in black and I can’t get along without Barney.’

“All right, I won’t bean him too hard.’

“Away they went, Thompson 50 feet above the flying Fiat. Down swooped the biplane on the back stretch until only inches separated the wheels from Barney’s head. Barney coaxed a few links out the Fiat and as they passed the stand the first time he was a full car length ahead of the biplane. Thompson stuck right above Barney’s poll all the way around the second time and finished with his propeller fanning Barney’s oily brow.

‘Mercy, didn’t he fly too low,’ said Mrs. Oldfield

‘Don’t you remember the race in Pittsburg,’ reminded Barney, ‘when he kept so low that I couldn’t get under him? You’re not going to collect any insurance on me, not even a strip of a tire on that kind of racing.’

“At the end of the race Thompson soared again and began dropping bombs on an impromptu fort in the middle of the enclosure while he was bombarded by a mortar within the fortification. He circled around like an eagle while the bombs cracked far behind him. The fort was soon on fire and the aviator ‘descended within the lines’ as they say in Europe.”

What a show it was. If they brought something like that to Les Bois Park today, there wouldn’t be any need to argue semantics about video racing machines.

#Idahohistory #boisehistory #barneyoldfield

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.  Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.

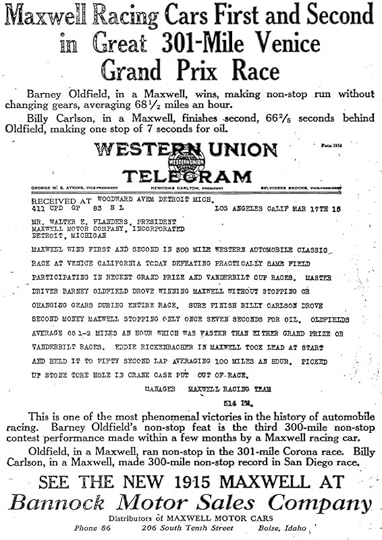

Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.  Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products.

Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products.

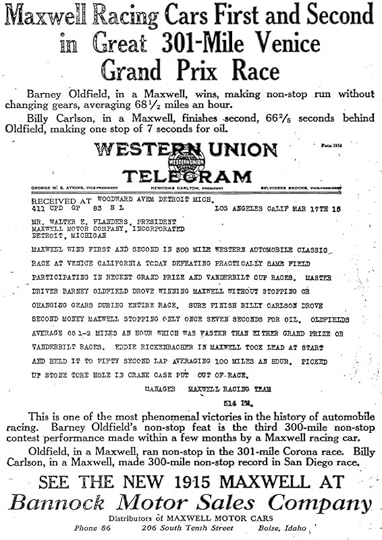

Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

His first major win came about because he took the corners like a motorcycle racer, allowing the rear end of the car to slide out or fishtail around a curve. At the 1902 Manufacturer’s Challenge Cup, Oldfield beat the reigning champion by half a mile in a five-mile race using the technique.

Oldfield’s need for speed became famous, Newspapers loved to carry stories about his breaking a speed limit in some town or another. He was the first man to reach the startling speed of 60 miles per hour and the first to take a turn at the Indianapolis Speedway at over 100 mph. Police reportedly were fond of asking citizen speeders they picked up if they thought they were Barney Oldfield.

Common headlines across the country in the early part of the Twentieth Century were variations of “Oldfield Smashes Record” again and again. He didn’t confine his efforts to only racing. Oldfield was always up for a stunt. In 1910 he raced Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson, toying with the man on the track by surging ahead and falling back to let him catch up. In a wire service story, he said, “I raced Jack Johnson neither for money or glory, but to eliminate from my profession an invader who would have had to be reckoned with sooner or later.” He would have said that with his signature cigar poking from the corner of his mouth. He found early on that one driver looked much like another after a race, covered in dust or mud, but the one with a cigar in his mouth stood out.

Oldfield became a sensation at county fairs all across the country. Prior to his appearance at the 1915 fairgrounds in Boise, The Idaho Statesman ran the following tease, “If neither Barney Oldfield, the world’s master driver, nor DeLoyd Thompson, the aerial marvel, is killed or injured when they present their series of sensational, spectacular and startling stunts on the massive Chicago speedway this afternoon, tonight they will commence their 1800-mile trip to appear in their nerve-tingling feats at the Boise race track on next Thursday afternoon.”

Boise Mayor Jeremiah W. Robinson climbed on board the hype train by declaring a “half holiday” the afternoon of June 24, the day of the exhibition of speed and daring. The Statesman piled on with “Thursday afternoon the clerks and other toilers, instead of simply visualizing the fear-chilling feats may, side by side with their employers, do what has been done in every other city where Thompson and Oldfield have shown—by their spontaneous and vociferous manifestations of appreciation demonstrate forcibly and indubitably that they coincide with the opinion of Mayor Robinson that each of these death cheaters is ‘without a peer in his line.’”

All the build-up worked. When the 24th rolled around the “largest crowd ever gathered in the city” turned out to see Oldfield and Thompson. There were 8,000 paid admissions.

Oldfield putted around the track in a couple of different cars, breaking the track record each time, for “the fastest mile ever traveled in Idaho,” according to the Statesman. Thompson, meanwhile, “soared aloft like a condor and tumbled to earth like a tumbler pigeon.”

Then the paper reported on the race with totally spontaneous and not at all scripted quotes. “The real excitement, with an accompaniment of comparative thrills, was produced by the race between Oldfield in his Flat Cyclone and Thompson in his biplane.

‘No cutting corners now,’ warned Barney as they got ready to start.

‘I don’t have to, to beat you in that old stinkpot, replied Thompson.

‘For mercy’s sake don’t fly too low this time,’ pleaded Mrs. Oldfield. “I look such a fright in black and I can’t get along without Barney.’

“All right, I won’t bean him too hard.’

“Away they went, Thompson 50 feet above the flying Fiat. Down swooped the biplane on the back stretch until only inches separated the wheels from Barney’s head. Barney coaxed a few links out the Fiat and as they passed the stand the first time he was a full car length ahead of the biplane. Thompson stuck right above Barney’s poll all the way around the second time and finished with his propeller fanning Barney’s oily brow.

‘Mercy, didn’t he fly too low,’ said Mrs. Oldfield

‘Don’t you remember the race in Pittsburg,’ reminded Barney, ‘when he kept so low that I couldn’t get under him? You’re not going to collect any insurance on me, not even a strip of a tire on that kind of racing.’

“At the end of the race Thompson soared again and began dropping bombs on an impromptu fort in the middle of the enclosure while he was bombarded by a mortar within the fortification. He circled around like an eagle while the bombs cracked far behind him. The fort was soon on fire and the aviator ‘descended within the lines’ as they say in Europe.”

What a show it was. If they brought something like that to Les Bois Park today, there wouldn’t be any need to argue semantics about video racing machines.

#Idahohistory #boisehistory #barneyoldfield

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.

DeLoyd Thompson in his biplane leading the race with Barney Oldfield at the Boise Fairgrounds in 1915.  Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.

Oldfield looks neck and neck with Thompson rounding the corner.  Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products.

Advertisers took full advantage of Oldfield’s fame to sell their products. Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

Can you imagine driving 301 miles at 68 ½ MPH without a stop?

Published on January 04, 2019 04:00

January 3, 2019

History, the Way Dan Valentine Told it

So, here’s a guy (me) who writes quirky little stories about Idaho history, writing about a guy who wrote quirky little stories about Idaho history. This post may eat its own tail.

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

#idahohistory #danvalentine

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

#idahohistory #danvalentine

Published on January 03, 2019 04:00

January 2, 2019

Son, You're Going to Drive Me to Drinkin'

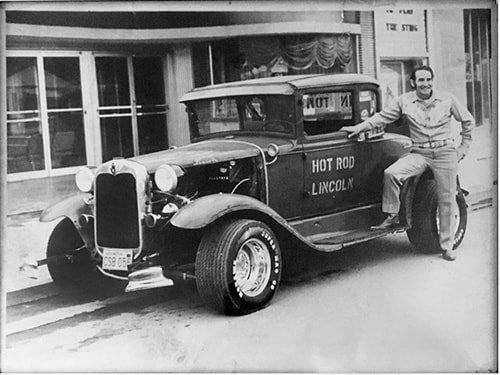

Joe Kaufman dropped a little tidbit a few weeks ago in a comment about my post on Lewiston Hill. He mentioned that the rockabilly song Hot Rod Lincoln, written by Charlie Ryan, was about an impromptu car race on Lewiston Hill. It didn’t take much digging for me to find out that Joe was right.

Charlie Ryan was playing at the Paradise Club in Lewiston when one night on his way back home to Spokane, he decided to race his ’41 Lincoln against a friend in a Caddy up the Lewiston grade. It was a seat-grabbing race that etched into the memory of the singer. Later he would write the lyrics, moving the fictional race to California on a road called Grapevine. Why? Artistic license, I suppose. Grapevine has the necessary two syllables for the line, while Lewiston would have been an awkward three. But another reason is probably that Grapevine is a straight shot, not like the Spiral Highway. The song doesn’t mention a corner at the end of every line, so that long highway worked better. It was called Grapevine not because it was twisty but because they had to slash through a lot of grapevines when building the road.

Charile’s song was something of a response to a song called Hot Rod Race, by Arkie Shelby that came out in 1951. There was a series of four back-and-forth racing songs.

Ryan released Hot Rod Lincoln in 1955 and did pretty well with it, the 45 staying on the Billboard chart for about a month. Charlie was on the charts again with the same song in 1959. Johnny Bond picked it up in 1960. His version was on the Billboard chart for seven weeks and climbed as high as 26. Then in 1971, Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen released what would be the most popular version of the song, reaching number 9 on the charts. George Frayne IV, alias Commander Cody, by the way, was born July 19, 1944 in Boise, Idaho. Over the years the song was certified to have sold more than a million records.

Commander Cody and crew may have had the big hit, but they did something that ruffled the feathers of many hot rod purists. They changed the Lincoln’s V-12 to a V-8. Shocking!

And, was there a real Hot Rod Lincoln? As mentioned above, yes. But Charlie built a second, nicer version of the car to match the song and toured with it as an attention grabber. The candy apple red 1934 Model A with the Lincoln V-12 sold for $97,000 to an Ohio doctor in 2013 who uses it as a charity fundraising prop.

One mystery remains about the song, though, at least for me. Here’s the line:

“That Model A Vitimix makes it look like a pup.”

What is Vitimix? At the risk of sounding like Google, did he mean Vitamix, which is a brand of blender? Some reader in the know will set me straight.

Charlie Ryan, who is in the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, died in 2008 at the age of 92.

#idahohistory #charlieryan #hotrodlincoln #lewiston #lewistonhill Publicity photo of Charlie Ryan.

Publicity photo of Charlie Ryan.

Charlie Ryan was playing at the Paradise Club in Lewiston when one night on his way back home to Spokane, he decided to race his ’41 Lincoln against a friend in a Caddy up the Lewiston grade. It was a seat-grabbing race that etched into the memory of the singer. Later he would write the lyrics, moving the fictional race to California on a road called Grapevine. Why? Artistic license, I suppose. Grapevine has the necessary two syllables for the line, while Lewiston would have been an awkward three. But another reason is probably that Grapevine is a straight shot, not like the Spiral Highway. The song doesn’t mention a corner at the end of every line, so that long highway worked better. It was called Grapevine not because it was twisty but because they had to slash through a lot of grapevines when building the road.

Charile’s song was something of a response to a song called Hot Rod Race, by Arkie Shelby that came out in 1951. There was a series of four back-and-forth racing songs.

Ryan released Hot Rod Lincoln in 1955 and did pretty well with it, the 45 staying on the Billboard chart for about a month. Charlie was on the charts again with the same song in 1959. Johnny Bond picked it up in 1960. His version was on the Billboard chart for seven weeks and climbed as high as 26. Then in 1971, Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen released what would be the most popular version of the song, reaching number 9 on the charts. George Frayne IV, alias Commander Cody, by the way, was born July 19, 1944 in Boise, Idaho. Over the years the song was certified to have sold more than a million records.

Commander Cody and crew may have had the big hit, but they did something that ruffled the feathers of many hot rod purists. They changed the Lincoln’s V-12 to a V-8. Shocking!

And, was there a real Hot Rod Lincoln? As mentioned above, yes. But Charlie built a second, nicer version of the car to match the song and toured with it as an attention grabber. The candy apple red 1934 Model A with the Lincoln V-12 sold for $97,000 to an Ohio doctor in 2013 who uses it as a charity fundraising prop.

One mystery remains about the song, though, at least for me. Here’s the line:

“That Model A Vitimix makes it look like a pup.”

What is Vitimix? At the risk of sounding like Google, did he mean Vitamix, which is a brand of blender? Some reader in the know will set me straight.

Charlie Ryan, who is in the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, died in 2008 at the age of 92.

#idahohistory #charlieryan #hotrodlincoln #lewiston #lewistonhill

Publicity photo of Charlie Ryan.

Publicity photo of Charlie Ryan.

Published on January 02, 2019 04:00

January 1, 2019

The Legendary Big Foot (No, not that one)

I’ll probably put my foot in it on this one. My average-sized foot.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, the Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868, and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope, and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

#Idahohistory #nampahistory #bigfoot The odd Bigfoot statue in Parma at the Old Fort Boise replica.

The odd Bigfoot statue in Parma at the Old Fort Boise replica.

Bigfoot was a legendary Indian. He was known for the enormous tracks he left. Those tracks were alleged to be 17 ½” long, large even for a man 6’ 6” tall. Allegedly.

Bigfoot’s tracks were said to have been seen often at the site of depredations perpetrated by indigenous people on immigrants, especially in Idaho and Oregon. He was always one step ahead of anyone trying to catch him. Stepping was part of the legend. He always walked or ran rather than ride a horse, the better to leave moccasin tracks, not doubt.

In November of 1878, the Idaho Statesman ran a sensational story about the death of Bigfoot, written by William T. Anderson of Fisherman’s Cove, Humboldt County, California, who had heard it from the man who killed him. It detailed the 16 bullets that went into Bigfoot’s body, fired by one John Wheeler, who caught up with him in Owyhee County. Both of the big man’s arms and both of his legs were broken by bullets in the fight with Wheeler. Knowing he was at death’s door, Bigfoot decided to tell Wheeler his life story. He did so in prose that Dick d’Easum who wrote about it years later for the Idaho Statesman said was packed with enough “frothy facts of his boyhood and manhood to fill a Theodore Dreiser novel.”

In the Anderson account of the death of Bigfoot, the man had an actual name. He was Starr Wilkinson, who was a lad living in the Cherokee nation when his father, a white man, was hanged for murder. His mother was of mixed blood, Negro and Cherokee. The drama of Bigfoot’s life went on for thousands of words, many of which were quite eloquent for a man gurgling them out with 16 bullet wounds in his body.

Odd that Wheeler himself never said anything about killing one of the most notorious bad men in the West. Odd that he didn’t collect the $1,000 reward on the man’s head. Wheeler had an outlaw record to his own credit. He killed a man on Wood River in 1868, and got away with it. He was sentenced to ten years in prison for a stagecoach robbery in Oregon. After leaving prison, he was eventually sentenced to hang for a murder committed during another stage robbery, this time in California.

Awaiting certain death, Wheeler wrote a series of letters to his wife, his sister, his attorney, and a girlfriend reflecting on his life. He wrote not a word about Bigfoot. His musings complete, Wheeler took poison in jail rather than face the rope, and died.

Many historians discount the whole legend of Bigfoot. Dick d’Easum put it this way: “Just as nobody is ever attacked by a little bear, no pioneer of the 1860s ever lost a steer or a wife or a set of harness to a small Indian. Little Indians were sometimes caught and killed. Dead Indians had little feet. Indians that prowled and pillaged and slipped away unscathed were invariably possessed of huge trotters.”

So, if Bigfoot was a myth, why would you name a town after him? That town is Nampa, reportedly taking its name from Shoshoni words Namp (foot) and Puh (big), and by some reports named after the legendary Bigfoot. Historian Annie Laurie Bird did research on the name Nampa in 1966, concluding that it probably did come from a Shoshoni word pronounced “nambe” or “nambuh” and meaning footprint. She did not weigh in on the Bigfoot connection.

A marauding giant is such a good story that it may never die. It was good enough that Bigfoot was killed, again, in New Mexico, 14 years after he was ventilated in Owyhee County. No word on whether he was able to gasp out his life story that time.

#Idahohistory #nampahistory #bigfoot

The odd Bigfoot statue in Parma at the Old Fort Boise replica.

The odd Bigfoot statue in Parma at the Old Fort Boise replica.

Published on January 01, 2019 04:00

December 31, 2018

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What was Mrs. Yakima Cannutt’s name?

A. Mabel

B. Montana

C. Kittie

D. Idaho

E. Agnes

2). What was Beaver Dick’s given name?

A. Richard Williams

B. Richard Leigh

C. Richard Grandjean

D. Richard Crowder

E. Richard Thompson

3). What unusual item did the C.C. Anderson Golden Rule store in Boise have on display in 1946?

A. A stone with William Clark’s name carved in it.

B. A stagecoach.

C. The Merci train car given to Idaho by the French.

D. A mounted sturgeon.

E. An airplane.

4). How did Sheepherder Bill die?

A. Suicide

B. Shot by Spanish Charley

C. His still blew up

D. Mine explosion

E. A sheep stampede

5) What Idaho scene painted by Thomas Moran hangs in the Oval Office?

A. Shoshone Falls

B. Mesa Falls

C. Portneuf Canyon

D. American Falls

E. The Idaho side of the Tetons Answers

Answers

1, C

2, B

3, E

4, C

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). What was Mrs. Yakima Cannutt’s name?

A. Mabel

B. Montana

C. Kittie

D. Idaho

E. Agnes

2). What was Beaver Dick’s given name?

A. Richard Williams

B. Richard Leigh

C. Richard Grandjean

D. Richard Crowder

E. Richard Thompson

3). What unusual item did the C.C. Anderson Golden Rule store in Boise have on display in 1946?

A. A stone with William Clark’s name carved in it.

B. A stagecoach.

C. The Merci train car given to Idaho by the French.

D. A mounted sturgeon.

E. An airplane.

4). How did Sheepherder Bill die?

A. Suicide

B. Shot by Spanish Charley

C. His still blew up

D. Mine explosion

E. A sheep stampede

5) What Idaho scene painted by Thomas Moran hangs in the Oval Office?

A. Shoshone Falls

B. Mesa Falls

C. Portneuf Canyon

D. American Falls

E. The Idaho side of the Tetons

Answers

Answers1, C

2, B

3, E

4, C

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on December 31, 2018 04:00

December 30, 2018

Idaho's Foot-Wide Towns

In the August 20, 1951 edition of Life Magazine there was an article entitled, “Idaho’s Foot-Wide Towns.” The article listed the towns of Banks, Garden City, Island Park, Batise, Chubbuck, Atomic City, and Island Park as examples of same. Crouch was the “foot-wide” town most prevalently featured, population 125, and 10 miles long.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

Published on December 30, 2018 04:00