Rick Just's Blog, page 217

November 8, 2018

Grover Cleveland Didn't Sleep Here

One step over from history is persistent, salacious rumor. Such is the story of Frieda Bethmann, one-time resident of Pardee, Idaho.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

Published on November 08, 2018 04:00

November 7, 2018

B.M. Bower

Who can we claim as an Idaho writer? Must they be born here, as Ezra Pound was? He had not learned to write his name when he moved away from the state, never to return. How about Ernest Hemingway, who wasn’t born here but lived and wrote in the state?

Or, how about someone who never really took up residence here, but wrote two novels in Idaho? Discuss among yourselves, but that criteria allows me to write a little Idaho story about an author who was wildly popular at one time.

B.M. Bower wrote, by my count, 68 novels—many still in print—and over a dozen screenplays. She is often favorably compared with Zane Grey, one of her contemporaries.

She was born Bertha Muzzy in 1871. Her family moved from Minnesota to a dryland homestead near Great Falls, Montana in 1889. At age 19, she eloped with a homesteader cowboy named Clayton Bower, thus giving her the pen name she would use for the rest of her life. Rather than Bertha Muzzy Bower, she chose B.M. so that readers could assume she was a man.

She would marry three men, divorcing two of them, and teaching one, her second husband Bill Sinclair, how to write a Western novel. He wrote 15 of his own.

Bower wrote her novels from homes in Montana, Washington, and California. She wrote two of them in Idaho, on brief visits. The Good Indian was written while she visited the ranch home of David Bliss, for whom Bliss, Idaho is named.

Bower’s second Idaho book was called Ranch at the Wolverine . She pumped that one out during a stay of about two months in 1913 at the home of my Great Aunt Agnes Just Reid, best known for her book Letters of Long Ago . The Just/Reid family home is in the Blackfoot River Valley below Wolverine Canyon. Agnes and B.M. spent much of that summer riding horses, exploring the canyon, and often riding into Blackfoot, about 15 miles away.

B.M. Bower loved to write details into her books from personal experience. In September 1913 the War Bonnet Roundup would take place in Idaho Falls. There was to be a women’s saddle horse race, and Bower talked Agnes into riding the 18 miles to the Roundup and entering the race the next day.

Agnes Just Reid remembered it this way: “Bower wanted to ride in the race for the sensation of it. Dressed in our long, divided, skirts of corduroy, so the wind would not blow them and show our ankles, we raced our fat, old cattle horses around the track far behind the professionals. But we got our sensation and the dust.”

Ranch of the Wolverine and The Good Indian are still in print.

In our family archives we have a B.M. Bower manuscript with charred edges that survived a fire in the home of Agnes and Robert E. Reid. When I learned that, I thought we might have a rare, unpublished novel by Bower. Alas, the manuscript was not unique and the novel was among the dozens she published.

Bower passed away in 1940 at age 69. Her friend, Agnes Just Reid, passed away in 1976 at age 90. B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Or, how about someone who never really took up residence here, but wrote two novels in Idaho? Discuss among yourselves, but that criteria allows me to write a little Idaho story about an author who was wildly popular at one time.

B.M. Bower wrote, by my count, 68 novels—many still in print—and over a dozen screenplays. She is often favorably compared with Zane Grey, one of her contemporaries.

She was born Bertha Muzzy in 1871. Her family moved from Minnesota to a dryland homestead near Great Falls, Montana in 1889. At age 19, she eloped with a homesteader cowboy named Clayton Bower, thus giving her the pen name she would use for the rest of her life. Rather than Bertha Muzzy Bower, she chose B.M. so that readers could assume she was a man.

She would marry three men, divorcing two of them, and teaching one, her second husband Bill Sinclair, how to write a Western novel. He wrote 15 of his own.

Bower wrote her novels from homes in Montana, Washington, and California. She wrote two of them in Idaho, on brief visits. The Good Indian was written while she visited the ranch home of David Bliss, for whom Bliss, Idaho is named.

Bower’s second Idaho book was called Ranch at the Wolverine . She pumped that one out during a stay of about two months in 1913 at the home of my Great Aunt Agnes Just Reid, best known for her book Letters of Long Ago . The Just/Reid family home is in the Blackfoot River Valley below Wolverine Canyon. Agnes and B.M. spent much of that summer riding horses, exploring the canyon, and often riding into Blackfoot, about 15 miles away.

B.M. Bower loved to write details into her books from personal experience. In September 1913 the War Bonnet Roundup would take place in Idaho Falls. There was to be a women’s saddle horse race, and Bower talked Agnes into riding the 18 miles to the Roundup and entering the race the next day.

Agnes Just Reid remembered it this way: “Bower wanted to ride in the race for the sensation of it. Dressed in our long, divided, skirts of corduroy, so the wind would not blow them and show our ankles, we raced our fat, old cattle horses around the track far behind the professionals. But we got our sensation and the dust.”

Ranch of the Wolverine and The Good Indian are still in print.

In our family archives we have a B.M. Bower manuscript with charred edges that survived a fire in the home of Agnes and Robert E. Reid. When I learned that, I thought we might have a rare, unpublished novel by Bower. Alas, the manuscript was not unique and the novel was among the dozens she published.

Bower passed away in 1940 at age 69. Her friend, Agnes Just Reid, passed away in 1976 at age 90.

B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Published on November 07, 2018 04:00

November 6, 2018

Chicken Dinner Road

Chicken dinner. Yum. It was yummy enough to get a road paved once in Canyon County.

The story about how Chicken Dinner Road got its name appeared in the Idaho Press Tribune in about 1992, and was reprinted in 2008. It seems that Morris and Laura Lamb were friends of Governor C. Ben Ross and his wife Edna. They had eaten dinner together many times at the Lamb home.

One day, in the 1930s, Mrs. Lamb, who was noted for her chicken, rolls, and apple pie meals, was in Boise. She invited the governor to come to dinner. During the same conversation, she complained to Ross about the pitiful condition of the road in front of their place, which was dirt pocked with potholes. Ross was purported to say something like, “Laura, if you get that road graded and graveled, I’ll see to it it’s oiled.

Mrs. Lamb approached the Canyon County Commissioners who saw that opportunity as a fine one. They graded and graveled the road. As soon as that was done, she was on the phone to the governor reminding him of his promise. The next day—this part seems unlikely, but it’s Mrs. Lamb’s story—the next day the road was oiled.

The story got around and local hooligans thought it would be droll to put up a big hand-scrawled sign in front of the Lamb house in the dark of night. It read “Lamb’s Chicken Dinner Avenue.” Mrs. Lamb was not amused. Still, the name stuck as Chicken Dinner Road.

Idaho Press Tribune writer Dave Wilkins penned the original story.

The story about how Chicken Dinner Road got its name appeared in the Idaho Press Tribune in about 1992, and was reprinted in 2008. It seems that Morris and Laura Lamb were friends of Governor C. Ben Ross and his wife Edna. They had eaten dinner together many times at the Lamb home.

One day, in the 1930s, Mrs. Lamb, who was noted for her chicken, rolls, and apple pie meals, was in Boise. She invited the governor to come to dinner. During the same conversation, she complained to Ross about the pitiful condition of the road in front of their place, which was dirt pocked with potholes. Ross was purported to say something like, “Laura, if you get that road graded and graveled, I’ll see to it it’s oiled.

Mrs. Lamb approached the Canyon County Commissioners who saw that opportunity as a fine one. They graded and graveled the road. As soon as that was done, she was on the phone to the governor reminding him of his promise. The next day—this part seems unlikely, but it’s Mrs. Lamb’s story—the next day the road was oiled.

The story got around and local hooligans thought it would be droll to put up a big hand-scrawled sign in front of the Lamb house in the dark of night. It read “Lamb’s Chicken Dinner Avenue.” Mrs. Lamb was not amused. Still, the name stuck as Chicken Dinner Road.

Idaho Press Tribune writer Dave Wilkins penned the original story.

Published on November 06, 2018 04:00

November 5, 2018

The Cabin

Today's post links to one of my recent columns in the Idaho Press.

Published on November 05, 2018 05:17

November 4, 2018

Sandpoint's Special Bridge

What do you do with a bridge that has outlived its usefulness? Often old bridges are sold and moved to a new location, or torn down for scrap. Not the Cedar Creek Bridge in Sandpoint.

The 400-foot-long bridge was built sometime in the 1920s so that pedestrians and cars could go from downtown Sandpoint to the railroad depot. As travel by rail became less popular, so did the bridge. By the 1970s it had fallen into disuse. The city blocked off the decaying bridge to traffic.

In the early 80s city officials were thinking about tearing it down when local entrepreneur Scott Glickenhaus approached them with an idea. He had seen the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, Italy. That bridge had housed shops as well as functioning as a bridge since the 13th century. Why not something like that in Sandpoint?

The derelict bridge was reinforced with new pilings, and a new enclosed structure was built on top of it from tamarack timbers. Shop spaces were built and rented. The bridge/mini-mall was opened in 1983. Coldwater Creek leased a small space on the bridge in 1988. Then a small mail-order retailer in Sandpoint, this was Coldwater Creek’s first retail store.

By 1995, Coldwater Creek had leased the entire bridge, which is about 16,000 square feet of space. In 2005 Coldwater Creek converted a downtown building for its use and moved out of the bridge.

A Sandpoint group purchased the bridge in 2006 and put over a million dollars into renovations. Today the Cedar Street Bridge hosts cart vendors, restaurants, gift shops, and boutiques and is a key feature of downtown Sandpoint.

The 400-foot-long bridge was built sometime in the 1920s so that pedestrians and cars could go from downtown Sandpoint to the railroad depot. As travel by rail became less popular, so did the bridge. By the 1970s it had fallen into disuse. The city blocked off the decaying bridge to traffic.

In the early 80s city officials were thinking about tearing it down when local entrepreneur Scott Glickenhaus approached them with an idea. He had seen the Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, Italy. That bridge had housed shops as well as functioning as a bridge since the 13th century. Why not something like that in Sandpoint?

The derelict bridge was reinforced with new pilings, and a new enclosed structure was built on top of it from tamarack timbers. Shop spaces were built and rented. The bridge/mini-mall was opened in 1983. Coldwater Creek leased a small space on the bridge in 1988. Then a small mail-order retailer in Sandpoint, this was Coldwater Creek’s first retail store.

By 1995, Coldwater Creek had leased the entire bridge, which is about 16,000 square feet of space. In 2005 Coldwater Creek converted a downtown building for its use and moved out of the bridge.

A Sandpoint group purchased the bridge in 2006 and put over a million dollars into renovations. Today the Cedar Street Bridge hosts cart vendors, restaurants, gift shops, and boutiques and is a key feature of downtown Sandpoint.

Published on November 04, 2018 04:00

November 3, 2018

Celebration on Lolo Pass

Lewis and Clark camped on top of Lolo Pass in September of 1805 when the Corps of Discovery began their trek through what is now Idaho. Glade Creek State Park preserves the area where they camped in close to its original condition.

Capt. John Mullan considered the pass as a crossing point for his road in 1858, but decided on a northern route instead. A $50,000 federal appropriation improved the pack trail across the pass a few years later.

Chief Joseph used the pass in evading pursuing troops during the Flight of the Nez Perce.

Lolo Pass seemed a natural route for a railroad connecting Montana with points west, and there was talk of one coming through for years. A railroad survey team did some preliminary work there in about 1900, improving a wagon road, but the idea of tracks across the mountain was abandoned.

In 1912 the federal government spent close to a quarter million dollars improving a 23-mile stretch through the canyon to better service the Powell and Lochsa ranger stations. In 1935 about 150 prisoners from the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth showed up to work on the road, and during World War II some of the Japanese “evacuees” from the West Coast did road work.

But it wasn’t until 1962 that the dream of following Lewis and Clark across Idaho in an automobile finally came true.

It was a watershed event for the region, so politicians showed up to celebrate the opening of the pass, as did hundreds of residents from both sides of the border. Ribbon cutting ceremonies are as boring as watching grass grow, so someone cooked up a twist: the governors of Idaho and Montana would push and pull a crosscut saw through a small log to dedicate the opening of US Highway 12, which runs from Aberdeen, Washington to Detroit, Michigan.

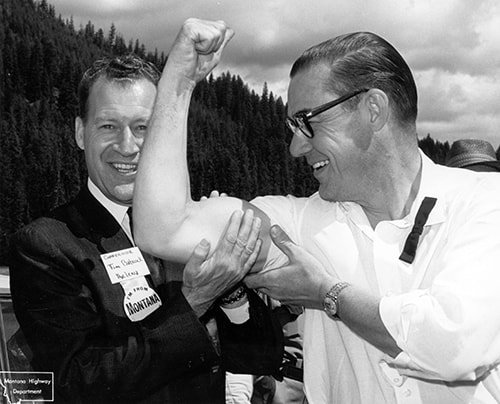

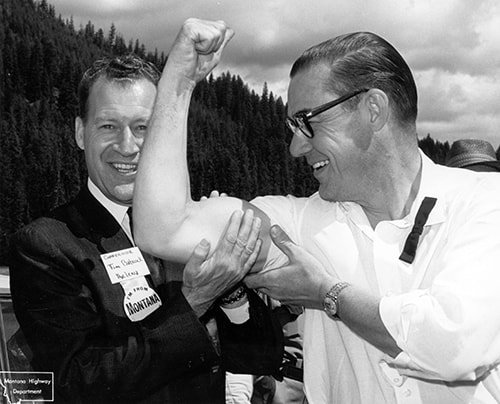

Idaho Governor Robert E. Smylie shows off his bicep to Montana Governor Tim Babcock prior to the log-sawing that would open Lolo Pass to the public September, 19, 1962.

Idaho Governor Robert E. Smylie shows off his bicep to Montana Governor Tim Babcock prior to the log-sawing that would open Lolo Pass to the public September, 19, 1962.

The ceremonial sawing takes place. These great photos, by the way, are all courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department's digital collection.

The ceremonial sawing takes place. These great photos, by the way, are all courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department's digital collection.  As a part of the celebration, “Pony Express” riders rode from Missoula to Lewiston. Here Governor Smylie “mails” a letter.

As a part of the celebration, “Pony Express” riders rode from Missoula to Lewiston. Here Governor Smylie “mails” a letter.  From left to right are Governor Smylie, Josiah Redwolf, Senator Frank Church, Montana Governor Babcock, and Senator Albert Gore (the senior) at the dedication. Gore was chairman of the Public Roads subcommittee of the Senate Public Works Committee in 1957 when funding decisions about the road were made. Josiah Redwolf (or Red Wolf), was five years old in 1877 when he rode across Lolo Pass with his grandfather, Hemene-Ilp-Pilp, and the rest of the Nez Perce on their way to Bear Paw, Montana, where their flight would ultimately come to its end.

From left to right are Governor Smylie, Josiah Redwolf, Senator Frank Church, Montana Governor Babcock, and Senator Albert Gore (the senior) at the dedication. Gore was chairman of the Public Roads subcommittee of the Senate Public Works Committee in 1957 when funding decisions about the road were made. Josiah Redwolf (or Red Wolf), was five years old in 1877 when he rode across Lolo Pass with his grandfather, Hemene-Ilp-Pilp, and the rest of the Nez Perce on their way to Bear Paw, Montana, where their flight would ultimately come to its end.

Planners made accommodations for 6,000 people at the opening of the road. No actual count is available, but this crowd shot shows that it was well attended. All photos are courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department’s digital archive.

Planners made accommodations for 6,000 people at the opening of the road. No actual count is available, but this crowd shot shows that it was well attended. All photos are courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department’s digital archive.

Capt. John Mullan considered the pass as a crossing point for his road in 1858, but decided on a northern route instead. A $50,000 federal appropriation improved the pack trail across the pass a few years later.

Chief Joseph used the pass in evading pursuing troops during the Flight of the Nez Perce.

Lolo Pass seemed a natural route for a railroad connecting Montana with points west, and there was talk of one coming through for years. A railroad survey team did some preliminary work there in about 1900, improving a wagon road, but the idea of tracks across the mountain was abandoned.

In 1912 the federal government spent close to a quarter million dollars improving a 23-mile stretch through the canyon to better service the Powell and Lochsa ranger stations. In 1935 about 150 prisoners from the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth showed up to work on the road, and during World War II some of the Japanese “evacuees” from the West Coast did road work.

But it wasn’t until 1962 that the dream of following Lewis and Clark across Idaho in an automobile finally came true.

It was a watershed event for the region, so politicians showed up to celebrate the opening of the pass, as did hundreds of residents from both sides of the border. Ribbon cutting ceremonies are as boring as watching grass grow, so someone cooked up a twist: the governors of Idaho and Montana would push and pull a crosscut saw through a small log to dedicate the opening of US Highway 12, which runs from Aberdeen, Washington to Detroit, Michigan.

Idaho Governor Robert E. Smylie shows off his bicep to Montana Governor Tim Babcock prior to the log-sawing that would open Lolo Pass to the public September, 19, 1962.

Idaho Governor Robert E. Smylie shows off his bicep to Montana Governor Tim Babcock prior to the log-sawing that would open Lolo Pass to the public September, 19, 1962. The ceremonial sawing takes place. These great photos, by the way, are all courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department's digital collection.

The ceremonial sawing takes place. These great photos, by the way, are all courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department's digital collection.  As a part of the celebration, “Pony Express” riders rode from Missoula to Lewiston. Here Governor Smylie “mails” a letter.

As a part of the celebration, “Pony Express” riders rode from Missoula to Lewiston. Here Governor Smylie “mails” a letter.  From left to right are Governor Smylie, Josiah Redwolf, Senator Frank Church, Montana Governor Babcock, and Senator Albert Gore (the senior) at the dedication. Gore was chairman of the Public Roads subcommittee of the Senate Public Works Committee in 1957 when funding decisions about the road were made. Josiah Redwolf (or Red Wolf), was five years old in 1877 when he rode across Lolo Pass with his grandfather, Hemene-Ilp-Pilp, and the rest of the Nez Perce on their way to Bear Paw, Montana, where their flight would ultimately come to its end.

From left to right are Governor Smylie, Josiah Redwolf, Senator Frank Church, Montana Governor Babcock, and Senator Albert Gore (the senior) at the dedication. Gore was chairman of the Public Roads subcommittee of the Senate Public Works Committee in 1957 when funding decisions about the road were made. Josiah Redwolf (or Red Wolf), was five years old in 1877 when he rode across Lolo Pass with his grandfather, Hemene-Ilp-Pilp, and the rest of the Nez Perce on their way to Bear Paw, Montana, where their flight would ultimately come to its end. Planners made accommodations for 6,000 people at the opening of the road. No actual count is available, but this crowd shot shows that it was well attended. All photos are courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department’s digital archive.

Planners made accommodations for 6,000 people at the opening of the road. No actual count is available, but this crowd shot shows that it was well attended. All photos are courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department’s digital archive.

Published on November 03, 2018 04:00

November 2, 2018

That Shiney Elevator

When the center part of Idaho’s capitol building was built in 1905, the part with the dome, you could ride a special elevator to the fourth floor where the Idaho Supreme Court met. Over the years the wings were added to the building for the Idaho House and Senate. Sometime during a remodel the elevator was covered up. They found it again during renovation in 2007. It would lead to the JFAC hearing room today, if it was operable. It isn’t worth maintaining, but it is so pretty they decided to open it up for you to see it. It’s easy to miss, so if you’re wandering around looking at the beautiful building, be sure you ask where the old elevator is.

Published on November 02, 2018 10:30

November 1, 2018

Pierce Park and the Plantation Golf Course

Today's post is a link to my latest column for Idaho Press.  Pierce Park postcards courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Pierce Park postcards courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Pierce Park postcards courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Pierce Park postcards courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on November 01, 2018 05:00

October 31, 2018

Betsey Ross

Not all that is written in stone is true. I did a post earlier about a monument memorializing a (probably) nonexistent massacre near Almo. We can trace the roots of that one and get at least an inkling of why the memorial exists. Not so with the memorial to Betsey Ross in the Forest Memorial Cemetery in Coeur d’Alene.

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Published on October 31, 2018 04:30

October 30, 2018

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). Who had a pretty good claim about naming Idaho?

A. Steamboat Captain Wilford Cromwell.

B. Chief Pocatello.

C. Lue Wallace.

D. Idaho’s first state governor, George Laird Shoup

E. Caleb Lyon, of Lyonsdale, NY.

2). Who was Maggie Hardy?

A. A prison warden in Oregon who invented the heavy device to attach to the shoes of prisoners.

B. A notorious murderess, possibly the first woman incarcerated in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

C. The wife of Idaho’s first territorial governor.

D. The first female publisher of the Idaho Statesman.

E. Known formally as Margaret, she was the subject of a bawdy song.

3). How many vessels have sailed the seas as the USS Idaho”

A. One.

B. Two.

C. Three.

D. Four.

E. Five.

4). How many appointments did President Ulysses S. Grant make before getting an Idaho territorial governor who wanted the job?

A. One.

B. Two.

C. Three.

D. Four.

E. Five.

5) What is William J. McConnell known for?

A. He ran one of the first commercial gardens in Idaho to supply miners with vegetables.

B. He was a vigilante.

C. He ran a general store in Moscow.

D. He was Idaho’s third governor.

E. All of the above.

Answers

Answers

1, C

2, B

3, D (there is a fifth under construction)

4, E

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). Who had a pretty good claim about naming Idaho?

A. Steamboat Captain Wilford Cromwell.

B. Chief Pocatello.

C. Lue Wallace.

D. Idaho’s first state governor, George Laird Shoup

E. Caleb Lyon, of Lyonsdale, NY.

2). Who was Maggie Hardy?

A. A prison warden in Oregon who invented the heavy device to attach to the shoes of prisoners.

B. A notorious murderess, possibly the first woman incarcerated in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

C. The wife of Idaho’s first territorial governor.

D. The first female publisher of the Idaho Statesman.

E. Known formally as Margaret, she was the subject of a bawdy song.

3). How many vessels have sailed the seas as the USS Idaho”

A. One.

B. Two.

C. Three.

D. Four.

E. Five.

4). How many appointments did President Ulysses S. Grant make before getting an Idaho territorial governor who wanted the job?

A. One.

B. Two.

C. Three.

D. Four.

E. Five.

5) What is William J. McConnell known for?

A. He ran one of the first commercial gardens in Idaho to supply miners with vegetables.

B. He was a vigilante.

C. He ran a general store in Moscow.

D. He was Idaho’s third governor.

E. All of the above.

Answers

Answers1, C

2, B

3, D (there is a fifth under construction)

4, E

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on October 30, 2018 04:30