Rick Just's Blog, page 219

October 19, 2018

Gobo Fango

Gobo Fango is not a name you often encounter in Idaho history, memorable as it is. Fango was born in Eastern Cape Colony of what is now South Africa in about 1855. He was a member of the Gcaleka tribe. He was saved from a bloody war with the British that would kill 100,000 of his people, only to end up the victim of a range war some 27 years later in Idaho Territory.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

Fango’s desperate, starving mother left him in the crook of a tree when he was three when she could no longer carry him. The sons of Henry and Ruth Talbot, English-speaking settlers, found him. The family adopted Gobo Fango. Or maybe they simply claimed him as property. In either case, they probably saved his life.

The Talbots became converts to the LDS religion. Records of their baptisms exist, though none such for Fango. They smuggled Fango out of the country and into the United States where they found their way to Utah in 1861.

Gobo Fango worked for the Talbots as an indentured servant, by some accounts, as a slave by others. He lived in a shed near their home. When a teenager he was sold, or given to another Mormon family.

Eventually Fango was on his own and working for a sheep operation near Oakley, in Idaho Territory. He was even able to acquire a herd of his own.

Cattlemen viewed sheep as a scourge that was destroying the range. Range wars broke out all over the West between sheep men and cattlemen.

It was one of those conflicts that brought an end to Gobo Fango.

The Idaho Territorial Legislature had passed a law known as the Two-Mile Limit intended to keep sheep grazers at least two miles away from a cattleman’s grazing claim. Early one day cattleman Frank Bedke and a companion rode into Fango’s camp to tell him he and his sheep were too close to Bedke’s claim and that he should leave. Fango resisted. Exactly what happened will never be known, but the black man ended up with a bullet passing through the back of his head and another tearing through his abdomen.

The cattlemen rode away. Gobo Fango, who, incredibly, was still alive, began crawling toward his employer’s home, holding his intestines in his hand as he dragged himself four and half miles.

Gobo Fango lived four or five days before succumbing to his wounds. He made out a will leaving his money and property to friends. Frank Bedke would be tried twice for his murder, with the first trial ending with a hung jury. The second time he was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

Published on October 19, 2018 04:30

October 18, 2018

Levy, Levy, and Levy's Alley

The first mention in the Idaho Statesman of what would become known as Levy’s Alley in Boise was on September 8, 1881. “D. Levy has laid the last brick in his new two-story brick building. This is one of the largest and best buildings in the city.” The article ended with the statement that this “will be one of the most desirable buildings in town to occupy.”

Well, there was much “desire” associated with Levy’s Alley occupants over the years. It became a well-known site of bordellos and independent entrepreneurial endeavors often associated with red lights. It was located where Boise City Hall is now located.

But we’re not going to address that unseemly side of Levy’s Alley today. We’re going to address the unseemly murder of Mr. Levy.

Davis Levy was well known in Boise for his monetary pursuits and for being miserly with his money. He had once been robbed of $80 by three men, but not before they literally put his feet to the fire to tell them where his money was. They stood him on the stove in his room until he gave in.

So it was assumed that robbery was the motive when on October 6, 1901, the Statesman headline shouted, “Davis Levy Foully Murdered” The newspaper made the most of the story, leading with, “Cold in death, the body of Davis Levy was yesterday found putrefying in one of the rooms of his Main Street block. The old man had been murdered by strangulation, a rope having been drawn about his neck and a gag forced into his mouth.” A more detailed description of the scene was provided and, as if that weren’t enough, a sketch of the room—complete with body—was included at the bottom of the article. Helpfully, I’ve included that below. You’re welcome.

Idaho Governor Frank H. Hunt issued an unusual proclamation related to the murder. It said in part,

“Whereas, It has been satisfactorily shown to me that he [Davis Levy] was the victim of a most atrocious and revolting murder committed by a person or persons unknown, and that the local authorities of the said city and county are unable to apprehend the murder or murderers,

Now, therefore, be it known that Frank W. Hunt, governor of the state of Idaho, by virtue of the authority in me vested, do hereby offer, on behalf of the said state of Idaho a reward of one thousand ($1000.00) dollars for the arrest and conviction of the murder or murderers of the said Davis Levy.”

Relatives of the murdered man put up another $3,000 to add to the reward.

On October 22, 1901 a man by the name of Joe Levy, also known as George Levy, was arrested for the murder in Baker City Oregon. That both men shared the same last name seemed not of interest to reporters at that time, though reports years later simply said that the two men were “related,” while other reports said they were not. It should be noted that Boise Police Chief B.F. Francis and Deputy Sheriff Andy J. Robinson arrested him. Really. Note that.

James Hawley presented the case for the state against Levy. Hawley would later find fame as a prosecutor in the Big Bill Haywood trial, and would also serve in future years as the mayor of Boise and Idaho’s ninth governor.

Witness after witness came forward to testify against Joe Levy. None of them had witnessed the murder, but they attested that he was acting strangely, that he held a grudge against Davis Levy, and that he had been nearby at the time. It was all circumstantial. Joe Levy, who was often described as “the Frenchman” proclaimed his innocence throughout the trial and long after he was sentenced to hang for the murder. Levy’s sentence was later reduced to life in prison.

There was considerable doubt about Levy’s guilt. One friend of the accused Levy, a Romanian immigrant named Bernat Edelberg, became so wildly adamant about Levy’s innocence that a judge declared him insane and committed him to the asylum in Blackfoot.

There was much concern that Boise Police Chief B.F. Francis and Deputy Sheriff Andy J. Robinson who had claimed the reward of $4,000 offered for his arrest and conviction had railroaded the man. Also of concern was the fact the Levy spoke little English and was not given a proper interpreter.

In 1911 there was enough pressure to review Levy’s sentence that the Idaho Board of Pardons agreed to give it a look. French authorities pleaded to have Levy pardoned. A letter signed by prominent citizens, and a petition signed by a large majority of businessmen in the city went to the board.

The Idaho Board of Pardons consisted of the governor, secretary of state, and attorney general. The governor was the same James Hawley who had prosecuted the original case. They voted unanimously to parole Levy on the condition that he leave the country.

So, George/Joe Levy left Idaho for France and lived happily ever after. No, I made that up.

Levy was pardoned in July, 1911 and shipped to Brussels. In September, the Idaho Statesman reported that he had been arrested in Portland on a charge of white slavery for bringing a French woman back to the U.S. for immoral purposes.

At the October, 1911 meeting of the Idaho Board of Parole the men who had so recently released Levy ordered him back to the Idaho State Penitentiary to serve the remainder of his life term.

But, federal authorities had custody of Levy, who was by then going by the handle “Blome the Tailor” and he had to face charges in federal court in New York. He was ultimately convicted of white slavery and sentenced to serve eight years in a federal prison in Atlanta.

Levy dropped off the face of the earth after that, as far as the Idaho Statesman was concerned, though the paper retold the story several times in succeeding years in their ___ years ago columns.

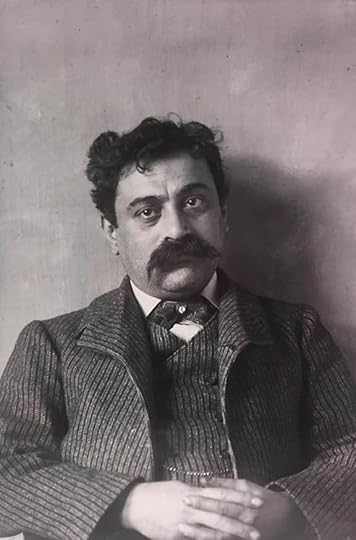

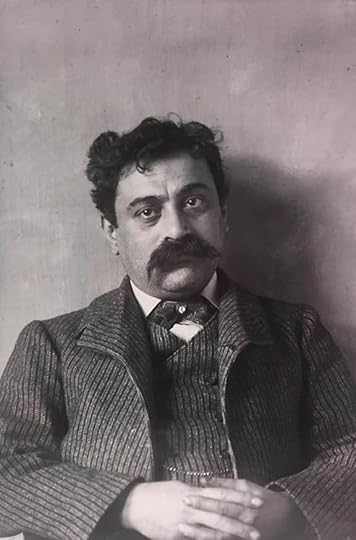

Joe (George) Levy at the time of his arrest for the murder of Davis Levy. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photos collection.

Joe (George) Levy at the time of his arrest for the murder of Davis Levy. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photos collection.  This sketch of the Levy murder scene appeared in the October 6, 1901 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

This sketch of the Levy murder scene appeared in the October 6, 1901 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

Well, there was much “desire” associated with Levy’s Alley occupants over the years. It became a well-known site of bordellos and independent entrepreneurial endeavors often associated with red lights. It was located where Boise City Hall is now located.

But we’re not going to address that unseemly side of Levy’s Alley today. We’re going to address the unseemly murder of Mr. Levy.

Davis Levy was well known in Boise for his monetary pursuits and for being miserly with his money. He had once been robbed of $80 by three men, but not before they literally put his feet to the fire to tell them where his money was. They stood him on the stove in his room until he gave in.

So it was assumed that robbery was the motive when on October 6, 1901, the Statesman headline shouted, “Davis Levy Foully Murdered” The newspaper made the most of the story, leading with, “Cold in death, the body of Davis Levy was yesterday found putrefying in one of the rooms of his Main Street block. The old man had been murdered by strangulation, a rope having been drawn about his neck and a gag forced into his mouth.” A more detailed description of the scene was provided and, as if that weren’t enough, a sketch of the room—complete with body—was included at the bottom of the article. Helpfully, I’ve included that below. You’re welcome.

Idaho Governor Frank H. Hunt issued an unusual proclamation related to the murder. It said in part,

“Whereas, It has been satisfactorily shown to me that he [Davis Levy] was the victim of a most atrocious and revolting murder committed by a person or persons unknown, and that the local authorities of the said city and county are unable to apprehend the murder or murderers,

Now, therefore, be it known that Frank W. Hunt, governor of the state of Idaho, by virtue of the authority in me vested, do hereby offer, on behalf of the said state of Idaho a reward of one thousand ($1000.00) dollars for the arrest and conviction of the murder or murderers of the said Davis Levy.”

Relatives of the murdered man put up another $3,000 to add to the reward.

On October 22, 1901 a man by the name of Joe Levy, also known as George Levy, was arrested for the murder in Baker City Oregon. That both men shared the same last name seemed not of interest to reporters at that time, though reports years later simply said that the two men were “related,” while other reports said they were not. It should be noted that Boise Police Chief B.F. Francis and Deputy Sheriff Andy J. Robinson arrested him. Really. Note that.

James Hawley presented the case for the state against Levy. Hawley would later find fame as a prosecutor in the Big Bill Haywood trial, and would also serve in future years as the mayor of Boise and Idaho’s ninth governor.

Witness after witness came forward to testify against Joe Levy. None of them had witnessed the murder, but they attested that he was acting strangely, that he held a grudge against Davis Levy, and that he had been nearby at the time. It was all circumstantial. Joe Levy, who was often described as “the Frenchman” proclaimed his innocence throughout the trial and long after he was sentenced to hang for the murder. Levy’s sentence was later reduced to life in prison.

There was considerable doubt about Levy’s guilt. One friend of the accused Levy, a Romanian immigrant named Bernat Edelberg, became so wildly adamant about Levy’s innocence that a judge declared him insane and committed him to the asylum in Blackfoot.

There was much concern that Boise Police Chief B.F. Francis and Deputy Sheriff Andy J. Robinson who had claimed the reward of $4,000 offered for his arrest and conviction had railroaded the man. Also of concern was the fact the Levy spoke little English and was not given a proper interpreter.

In 1911 there was enough pressure to review Levy’s sentence that the Idaho Board of Pardons agreed to give it a look. French authorities pleaded to have Levy pardoned. A letter signed by prominent citizens, and a petition signed by a large majority of businessmen in the city went to the board.

The Idaho Board of Pardons consisted of the governor, secretary of state, and attorney general. The governor was the same James Hawley who had prosecuted the original case. They voted unanimously to parole Levy on the condition that he leave the country.

So, George/Joe Levy left Idaho for France and lived happily ever after. No, I made that up.

Levy was pardoned in July, 1911 and shipped to Brussels. In September, the Idaho Statesman reported that he had been arrested in Portland on a charge of white slavery for bringing a French woman back to the U.S. for immoral purposes.

At the October, 1911 meeting of the Idaho Board of Parole the men who had so recently released Levy ordered him back to the Idaho State Penitentiary to serve the remainder of his life term.

But, federal authorities had custody of Levy, who was by then going by the handle “Blome the Tailor” and he had to face charges in federal court in New York. He was ultimately convicted of white slavery and sentenced to serve eight years in a federal prison in Atlanta.

Levy dropped off the face of the earth after that, as far as the Idaho Statesman was concerned, though the paper retold the story several times in succeeding years in their ___ years ago columns.

Joe (George) Levy at the time of his arrest for the murder of Davis Levy. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photos collection.

Joe (George) Levy at the time of his arrest for the murder of Davis Levy. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society physical photos collection.  This sketch of the Levy murder scene appeared in the October 6, 1901 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

This sketch of the Levy murder scene appeared in the October 6, 1901 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

Published on October 18, 2018 04:30

October 17, 2018

First Women

In 1896, Idaho became the fourth state in the nation—preceded by Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah—to give women the right to vote. If you want to get technical, Idaho was actually the second state to do so, since Wyoming and Utah were both territories at the time. This was 23 years ahead of the 19th Amendment which gave that right to all women in the United States.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and the perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with divers men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband hand slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

It wasn’t just voting that interested women. They wanted to be a part of the political process at every level. In 1898 voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature, Mrs. Mary Wright from Kootenai County (left in the photo), Mrs. Hattie Noble from Boise County, and Mrs. Clara Pamelia Campbell from Ada County. It was the fifth Idaho Legislature.

On February 8, 1899, the Idaho Daily Statesman noted that Mrs. Wright had become the first woman to preside over the Idaho Legislature, and the perhaps the first to preside over any legislature in the nation. She was chairman of the committee of the whole during the preceding afternoon and “ruled with a firm but impartial hand.”

Mary Wright was elected Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives, and went on to take a job as the private secretary of Congressman Thomas Glenn.

All of this seemed not to sit well with her husband, who “filed a red hot divorce bill” according the Idaho Statesman, reporting on the proceedings in a Sandpoint court in the April 26, 1904 edition. Mr. Wright claimed that while in the legislature in Boise she “mingled with divers men, at improper hours and times, making appointments with strange men at committee rooms and hotels.” He also claimed she lost $2,000 on the board of trade, and “used improper language before their son, a lad of 16.”

Mrs Wright shot back with a suit of her own claiming her husband hand slandered her. The paper reported that “She produced two witnesses in court and showed that Wright had done little toward her support in years.” The divorce was granted… In favor of Mrs. Wright.

Published on October 17, 2018 04:30

October 16, 2018

Two Montpeliers

The U.S. Postal Service, famously, would not allow two towns with the same name in a single state. That’s why we don’t have two Eagle, Idahos. The town of Sagle, in North Idaho applied to be Eagle, but the postal folks said no, so they just changed the first letter of the name.

But, for a couple of decades there were effectively two towns named Montpelier. The post office didn’t recognize that reality, but the residents did.

When Montpelier residents heard that the railroad was coming to town there was a division of opinion. Some saw it as progress and opportunity. Some, such as wagon freighters, saw it as competition they didn’t need. There was another fear many residents had: Gentiles.

Montpelier was one of several towns in Bear Lake Valley that had been created during Mormon colonization of Southern Idaho. The Mormons had experienced quite a lot of persecution in the short history of the church. What if the railroad encouraged settlement by non-Mormons?

One of the more progressive citizens of the community, Edward Burgoyne, sold a right-of-way to the Oregon Shortline, along with timber for ties and grading work. So, on July 24, 1882, the first train arrived in Montpelier.

To show their disdain for the non-Mormons who did indeed start moving in because of the opportunities the railroad provided, citizens of what became Uptown Montpelier built a fence between their Mormon community and the developing Gentile community that was called Downtown Montpelier. A gate would let people pass from one to the other, but Uptown Montpelier parents warned their children to avoid the evils on the wrong side. Those evils included the saloons that had sprung up Downtown.

Each “town” had its own business district, school, recreation center, and churches.

The split between the communities was only exacerbated by federal anti-polygamy laws, which US Marshall Fred T. Dubois began enthusiastically enforcing in 1884. Idaho laws for a time kept Mormons from voting, holding office, or serving on a jury. Again, this effectively reinforced that fence.

Anti-Mormon rhetoric subsided somewhat in Idaho in the late 1880s, and people on both sides of the fence began to prosper from the railroad. By 1890 the town had grown to 1174 residents, second only in population to Boise, according to that year’s census (though it must be noted that Pocatello, Idaho Falls, Moscow, and Rexburg didn’t show up in that census, for some reason).

Leaders on both sides began to work together more, and by 1891 there was a unified city council in place. The fence came down, at some point, though some Uptown/Downtown squabbles continued. As late as 1906 there was a dust-up over which “town” would have the post office.

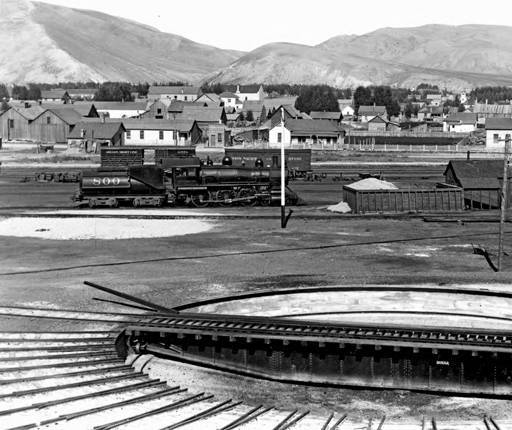

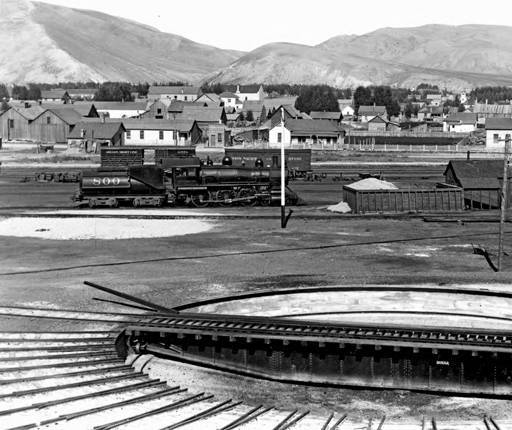

Montpelier in 1892 with repair shops and buildings in the background and locomotive Number 800 in the the middle distance. A repair turntable is in the foreground.. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Montpelier in 1892 with repair shops and buildings in the background and locomotive Number 800 in the the middle distance. A repair turntable is in the foreground.. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

But, for a couple of decades there were effectively two towns named Montpelier. The post office didn’t recognize that reality, but the residents did.

When Montpelier residents heard that the railroad was coming to town there was a division of opinion. Some saw it as progress and opportunity. Some, such as wagon freighters, saw it as competition they didn’t need. There was another fear many residents had: Gentiles.

Montpelier was one of several towns in Bear Lake Valley that had been created during Mormon colonization of Southern Idaho. The Mormons had experienced quite a lot of persecution in the short history of the church. What if the railroad encouraged settlement by non-Mormons?

One of the more progressive citizens of the community, Edward Burgoyne, sold a right-of-way to the Oregon Shortline, along with timber for ties and grading work. So, on July 24, 1882, the first train arrived in Montpelier.

To show their disdain for the non-Mormons who did indeed start moving in because of the opportunities the railroad provided, citizens of what became Uptown Montpelier built a fence between their Mormon community and the developing Gentile community that was called Downtown Montpelier. A gate would let people pass from one to the other, but Uptown Montpelier parents warned their children to avoid the evils on the wrong side. Those evils included the saloons that had sprung up Downtown.

Each “town” had its own business district, school, recreation center, and churches.

The split between the communities was only exacerbated by federal anti-polygamy laws, which US Marshall Fred T. Dubois began enthusiastically enforcing in 1884. Idaho laws for a time kept Mormons from voting, holding office, or serving on a jury. Again, this effectively reinforced that fence.

Anti-Mormon rhetoric subsided somewhat in Idaho in the late 1880s, and people on both sides of the fence began to prosper from the railroad. By 1890 the town had grown to 1174 residents, second only in population to Boise, according to that year’s census (though it must be noted that Pocatello, Idaho Falls, Moscow, and Rexburg didn’t show up in that census, for some reason).

Leaders on both sides began to work together more, and by 1891 there was a unified city council in place. The fence came down, at some point, though some Uptown/Downtown squabbles continued. As late as 1906 there was a dust-up over which “town” would have the post office.

Montpelier in 1892 with repair shops and buildings in the background and locomotive Number 800 in the the middle distance. A repair turntable is in the foreground.. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Montpelier in 1892 with repair shops and buildings in the background and locomotive Number 800 in the the middle distance. A repair turntable is in the foreground.. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection.

Published on October 16, 2018 05:00

October 14, 2018

USS Idaho(s)

I’ve spent a few posts talking about how Idaho got its name and what the name might or might not mean. It’s time to do one on things named after the state of Idaho, in this case naval vessels. Arguably Idaho owes its name to a boat, the steamer Idaho. Inarguably, there have been four naval vessels named after the state… Unless you want to argue that the one currently under construction counts as an existing vessel. In that case, five USS Idahos.

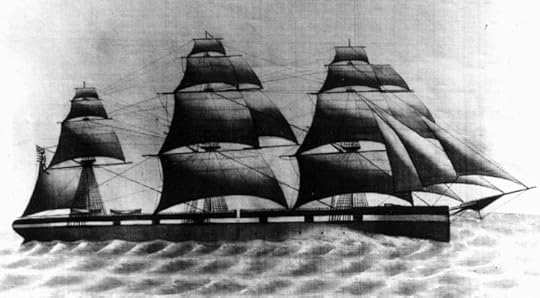

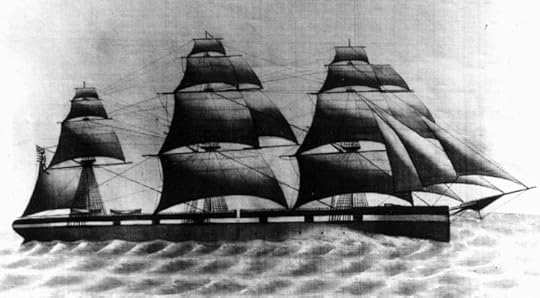

The first USS Idaho (above) was named in 1864, shortly after Idaho became a territory. It was a 3,241-ton wooden steam sloop. She didn’t set sail until May of 1866. She was disappointing, in that the Idaho was hyped as a ship that would make 15 knots and she could only squeeze out about eight. Congress, being Congress, bought the boat anyway, despite her not living up to her specs. But it was a fast boat the U.S. Navy was after, so the Idaho was outfitted with sails to augment her steam power to push her to 18 knots, and she became one of the fasted ships in the fleet.

The first USS Idaho (above) was named in 1864, shortly after Idaho became a territory. It was a 3,241-ton wooden steam sloop. She didn’t set sail until May of 1866. She was disappointing, in that the Idaho was hyped as a ship that would make 15 knots and she could only squeeze out about eight. Congress, being Congress, bought the boat anyway, despite her not living up to her specs. But it was a fast boat the U.S. Navy was after, so the Idaho was outfitted with sails to augment her steam power to push her to 18 knots, and she became one of the fasted ships in the fleet.

The Idaho served as a hospital ship in Japan for 15 months, then started back to the U.S. On the way she was hit by a roaring typhoon and de-masted. Decommissioned in 1873, the hulk was eventually sold to the East Indies Trading Company. The second USS Idaho (above), also known as Battleship No. 24, was ordered in 1903 and commissioned in 1908. As Milton said, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” The Idaho sailed here and there arriving unscathed by battle in the French port of Villefranche in 1914 where she was decommissioned and sold to the Greek Navy. She served there, no doubt without her original name, for 27 years before being sunk during WWII.

The second USS Idaho (above), also known as Battleship No. 24, was ordered in 1903 and commissioned in 1908. As Milton said, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” The Idaho sailed here and there arriving unscathed by battle in the French port of Villefranche in 1914 where she was decommissioned and sold to the Greek Navy. She served there, no doubt without her original name, for 27 years before being sunk during WWII.

The third USS Idaho (above) was not a battleship at all, and probably counts as the weirdest of her cousins. She was a privately owned, 60-foot-long motorboat the U.S. Navy purchased during World War I. SP-545 was commissioned in 1917, and served as a patrol boat mostly in the Philadelphia area guarding the harbor and checking submarine nets. No longer needed at war’s end, the 24-ton boat was returned to her owner in November of 1918.

The third USS Idaho (above) was not a battleship at all, and probably counts as the weirdest of her cousins. She was a privately owned, 60-foot-long motorboat the U.S. Navy purchased during World War I. SP-545 was commissioned in 1917, and served as a patrol boat mostly in the Philadelphia area guarding the harbor and checking submarine nets. No longer needed at war’s end, the 24-ton boat was returned to her owner in November of 1918.

The fourth USS Idaho, shown above sailing under the Brooklyn Bridge, saw the most action. BB-42 was commissioned in 1919 and spent the pre-WWII years in the Pacific doing training exercises. In 1941, before the U.S. entered the war several ships, including the Idaho, were sent to the Atlantic to protect shipping interests while the U.S. remained neutral. As a result, she was not part of the Pacific Fleet when Pearl Harbor was attacked. She and her sister ships moved back into the Pacific for the duration of the war.

The fourth USS Idaho, shown above sailing under the Brooklyn Bridge, saw the most action. BB-42 was commissioned in 1919 and spent the pre-WWII years in the Pacific doing training exercises. In 1941, before the U.S. entered the war several ships, including the Idaho, were sent to the Atlantic to protect shipping interests while the U.S. remained neutral. As a result, she was not part of the Pacific Fleet when Pearl Harbor was attacked. She and her sister ships moved back into the Pacific for the duration of the war.

The Idaho shelled Japanese forces during several island campaigns and she was there for the invasions of Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. The USS Idaho was also in Tokyo Bay for the formal surrender of the Japanese. The ship was decommissioned in 1946 and scrapped.

The fifth USS Idaho has yet to ply the waters of the world, on or below them. SSN 799 will be a Virginia-Class submarine. That’s the USS Virginia in the photo above. Commissioned in 2014, the nuclear sub is currently under construction. When launched, it will have a crew of 135 and will be capable of staying submerged for three months at a time. It will be fast, though that is a relative term. The sub will be able to cruise at 25 knots, which is a bit more than the first USS Idaho, that 18-knot steamer/sailboat.

The fifth USS Idaho has yet to ply the waters of the world, on or below them. SSN 799 will be a Virginia-Class submarine. That’s the USS Virginia in the photo above. Commissioned in 2014, the nuclear sub is currently under construction. When launched, it will have a crew of 135 and will be capable of staying submerged for three months at a time. It will be fast, though that is a relative term. The sub will be able to cruise at 25 knots, which is a bit more than the first USS Idaho, that 18-knot steamer/sailboat.

The first USS Idaho (above) was named in 1864, shortly after Idaho became a territory. It was a 3,241-ton wooden steam sloop. She didn’t set sail until May of 1866. She was disappointing, in that the Idaho was hyped as a ship that would make 15 knots and she could only squeeze out about eight. Congress, being Congress, bought the boat anyway, despite her not living up to her specs. But it was a fast boat the U.S. Navy was after, so the Idaho was outfitted with sails to augment her steam power to push her to 18 knots, and she became one of the fasted ships in the fleet.

The first USS Idaho (above) was named in 1864, shortly after Idaho became a territory. It was a 3,241-ton wooden steam sloop. She didn’t set sail until May of 1866. She was disappointing, in that the Idaho was hyped as a ship that would make 15 knots and she could only squeeze out about eight. Congress, being Congress, bought the boat anyway, despite her not living up to her specs. But it was a fast boat the U.S. Navy was after, so the Idaho was outfitted with sails to augment her steam power to push her to 18 knots, and she became one of the fasted ships in the fleet. The Idaho served as a hospital ship in Japan for 15 months, then started back to the U.S. On the way she was hit by a roaring typhoon and de-masted. Decommissioned in 1873, the hulk was eventually sold to the East Indies Trading Company.

The second USS Idaho (above), also known as Battleship No. 24, was ordered in 1903 and commissioned in 1908. As Milton said, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” The Idaho sailed here and there arriving unscathed by battle in the French port of Villefranche in 1914 where she was decommissioned and sold to the Greek Navy. She served there, no doubt without her original name, for 27 years before being sunk during WWII.

The second USS Idaho (above), also known as Battleship No. 24, was ordered in 1903 and commissioned in 1908. As Milton said, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” The Idaho sailed here and there arriving unscathed by battle in the French port of Villefranche in 1914 where she was decommissioned and sold to the Greek Navy. She served there, no doubt without her original name, for 27 years before being sunk during WWII.  The third USS Idaho (above) was not a battleship at all, and probably counts as the weirdest of her cousins. She was a privately owned, 60-foot-long motorboat the U.S. Navy purchased during World War I. SP-545 was commissioned in 1917, and served as a patrol boat mostly in the Philadelphia area guarding the harbor and checking submarine nets. No longer needed at war’s end, the 24-ton boat was returned to her owner in November of 1918.

The third USS Idaho (above) was not a battleship at all, and probably counts as the weirdest of her cousins. She was a privately owned, 60-foot-long motorboat the U.S. Navy purchased during World War I. SP-545 was commissioned in 1917, and served as a patrol boat mostly in the Philadelphia area guarding the harbor and checking submarine nets. No longer needed at war’s end, the 24-ton boat was returned to her owner in November of 1918.  The fourth USS Idaho, shown above sailing under the Brooklyn Bridge, saw the most action. BB-42 was commissioned in 1919 and spent the pre-WWII years in the Pacific doing training exercises. In 1941, before the U.S. entered the war several ships, including the Idaho, were sent to the Atlantic to protect shipping interests while the U.S. remained neutral. As a result, she was not part of the Pacific Fleet when Pearl Harbor was attacked. She and her sister ships moved back into the Pacific for the duration of the war.

The fourth USS Idaho, shown above sailing under the Brooklyn Bridge, saw the most action. BB-42 was commissioned in 1919 and spent the pre-WWII years in the Pacific doing training exercises. In 1941, before the U.S. entered the war several ships, including the Idaho, were sent to the Atlantic to protect shipping interests while the U.S. remained neutral. As a result, she was not part of the Pacific Fleet when Pearl Harbor was attacked. She and her sister ships moved back into the Pacific for the duration of the war.The Idaho shelled Japanese forces during several island campaigns and she was there for the invasions of Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. The USS Idaho was also in Tokyo Bay for the formal surrender of the Japanese. The ship was decommissioned in 1946 and scrapped.

The fifth USS Idaho has yet to ply the waters of the world, on or below them. SSN 799 will be a Virginia-Class submarine. That’s the USS Virginia in the photo above. Commissioned in 2014, the nuclear sub is currently under construction. When launched, it will have a crew of 135 and will be capable of staying submerged for three months at a time. It will be fast, though that is a relative term. The sub will be able to cruise at 25 knots, which is a bit more than the first USS Idaho, that 18-knot steamer/sailboat.

The fifth USS Idaho has yet to ply the waters of the world, on or below them. SSN 799 will be a Virginia-Class submarine. That’s the USS Virginia in the photo above. Commissioned in 2014, the nuclear sub is currently under construction. When launched, it will have a crew of 135 and will be capable of staying submerged for three months at a time. It will be fast, though that is a relative term. The sub will be able to cruise at 25 knots, which is a bit more than the first USS Idaho, that 18-knot steamer/sailboat.

Published on October 14, 2018 05:00

October 13, 2018

Bear Track Williams

Not all property owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (IDPR) is a state park. One little known site is called “Bear Track” Williams Recreation Area. Though owned by IDPR, it is managed by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. That’s because the site is primarily for fishing access.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Two parcels, totaling 480 acres, are along Hwy 93 between Carey and Richfield, near Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Ernest Hemingway’s son, Jack, donated the property to the Idaho Foundation for Parks and Lands in 1973, with the intent that they would turn it over to the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation when the donation could be used as a match for acquisition or development of state park property.

IDPR took over ownership of two parcels in 1974 and 1975.

Jack Hemingway purchased the property with the intention of making the donation and specifying that it be named for Taylor “Bear Tracks” Williams.

So, who was “Bear Tracks” Williams? He was one of several hunting and fishing guides who began working in the Wood River Valley when Averell Harriman built his famous Sun Valley Resort. The guides often found themselves rubbing shoulders with the wealthy and famous. Williams guided for Ernest Hemingway, and they became good friends. He often accompanied Hemingway to Cuba. They spent many hours together along Silver Creek and the Little Wood River.

One would assume this outdoor guide got his nickname because of his proficiency in tracking or because of some harrowing tale. Nope. He got the nickname because he walked with his toes pointed out.

“Bear Tracks” Williams Recreation Area is prized for its angling opportunities in the sagebrush desert. Fly fishing there is catch and release. There has been virtually no development on the site since Jack Hemingway donated it more than 40 years ago, which is probably just the way he would have wanted it.

Published on October 13, 2018 04:30

October 12, 2018

Maggie Hardy

,The first mention of Margaret Hardy in the Idaho Statesman, on February 13, 1895, included the line, “Sensational developments are promised.” Oh, my.

Latah County’s first murder case would more than live up to that tease. Hardy, often called Maggie, sometimes called “Old Woman Hardy,” and once called a “black hearted old hag” by the Statesman, would soon enough be the only woman in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Hardy had an infamous past. She lived in Utah, Colorado, and Oregon, before moving to Idaho. Each stop on her life’s journey included rumors of prostitution, theft, and the running of bordellos. In Aspen she was charged with “despoiling” the golden hair of a seven-year-old girl, by cutting it off. Years of morphine addiction caught up with her in 1893 and she was sent to the Keeley Institute in Forest Grove, Oregon. Upon release the now “cured” woman and her husband Harvey moved to Pendleton, where a suicide attempt landed her in the state insane asylum in Salem, later infamous itself as the setting of the Ken Kesey novel and motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest .”

After her release from that institution the Hardys moved to Moscow, Idaho, where Maggie quickly became known for a string of minor crimes and for her wicked temper.

Harvey and Maggie soon moved to Lewiston where they acquired housemates. A prostitute named Anna Meyers described by the press as “colored” lived with them, along with the woman’s toddler child, Henrietta. Harvey apparently strayed with the woman, inciting Maggie’s famous temper. Explosive as that temper could be, she took a calculated course of revenge.

Maggie made a show of reconciling with Harvey, because he was to play a part in her revenge. She talked Harvey into helping her adopt 2-year-old Henrietta. The girl’s mother did not at first consent, but ultimately put her X on a document granting custody to the Hardys. Just to Maggie Hardy, as it turned out. As soon as she got custody of Henrietta, Maggie moved back to Moscow, leaving Harvey and Anna to resume their relationship.

Within days, Maggie let it be known that she planned to poison Henrietta, then kill her mother and Harvey, and finally to commit suicide herself. Why no one intervened is unknown, though crossing the woman famous for her foul temper might have given some pause.

On Sunday, February 10, 1895 some terrible things happened. The way Maggie told it, she had prepared a large dose of morphine for herself, meaning to take her own life that way. She put that on the counter along with a glass filled with carbolic acid. It was not uncommon for people to commit suicide by swallowing carbolic acid, which would eat away the mouth, esophagus, and lungs. It was a hideous way to go.

Gosh, though, she got distracted from her suicide by something. When she returned to the room, she claimed she saw that Henrietta had found and swallowed the morphine, then tipped over the carbolic acid, spreading it all over her face though, oddly, not her hands. Henrietta was dead, her face and neck horribly disfigured and one eye eaten away.

Maggie’s story was believed by approximately no one, perhaps in part because she had earlier threatened to poison the child. Mrs. Hardy was arrested for murder.

While awaiting trial she went “suddenly stark crazy.” The sheriff figured she was angling for an insanity plea, though many who knew her thought she was never far from the mental abyss.

Hardy was charged with second degree murder because the prosecutor thought the mandatory death sentence by hanging might cause second thoughts when considering the conviction of a woman.

The jury heard arguments for a couple of days. The defense team noted that no autopsy had been done, so charging the woman with a poisoning should not hold up. They rested their case and the jury retired to deliberate. They did so all night, returning with a verdict of guilty the next morning. Maggie flew into a rage, condemning the jury, the judge, and every handy lawyer in the most vile terms.

Hoping for another outburst, the courtroom was packed on March 19 when she appeared for sentencing. To the disappointment of onlookers she sat quietly while the judge sentenced her to life in prison.

In Boise Maggie Hardy, 48, made another name for herself. Officials at the prison began calling her “Mad Margaret” because of her rages. She would howl like a wolf for days. She complained of terrible stomach pains. The pains she was experiencing, according to an inmate who travelled to the prison with her, were likely caused by here attempt to commit suicide by eating glass. Doctors saw no sign that she had done so. Her next suicide attempt was real enough. She and another inmate were being kept in a small building with side-by-side cells. The neighboring prisoner smelled smoke and began to feel heat. He yelled for help. When help arrived they found that Maggie had piled together her bed clothes and set them on fire. She was found huddled in a corner “peering through the flame and smoke, a fiendish grin on her face.”

On June 20, the superintendent of the Idaho State Insane Asylum in Blackfoot stopped by the prison to evaluate Maggie. He pronounced her “entirely sane.”

Warden John Campbell was determined to break the woman of her antics. His remedy was to build a tight, little, windowless cell for Maggie, keeping her in isolation. Seven months of such harsh treatment did little to improve Maggie’s condition, so she was shipped off to the Insane Asylum.

What happened to Maggie Hardy after that is not entirely certain. She was listed on an institution information card in Blackfoot that included the notes “Delusions of grandeur and persecution. Abnormally irritable.” Oddly, the note also included the word “dead.”

Yet, she seemed to show up one last time in the February 27, 1906 issue of the Pendelton Eastern Oregonian. The paper reported that her incinerated remains were discovered in the rubble of burned residence where she had been working as a housekeeper. When or why she was released from the asylum is lost to history’s dust.

My thanks to Steven Branting for bringing this story to my attention and sending me much information. A more detailed story about Maggie Hardy can be found in his well-written book, Wicked Lewiston .

This admission sheet, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Archives, tells a story. It's not necessarily an accurate one, according to Steven Branting, who has done a lot of research on Maggie Hardy. She was probably never a nurse, she wasn't born in Utah, and she was not illiterate. One chilling notation is that she had one child. Was that Henrietta she was reporting on?

This admission sheet, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Archives, tells a story. It's not necessarily an accurate one, according to Steven Branting, who has done a lot of research on Maggie Hardy. She was probably never a nurse, she wasn't born in Utah, and she was not illiterate. One chilling notation is that she had one child. Was that Henrietta she was reporting on?

Latah County’s first murder case would more than live up to that tease. Hardy, often called Maggie, sometimes called “Old Woman Hardy,” and once called a “black hearted old hag” by the Statesman, would soon enough be the only woman in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

Hardy had an infamous past. She lived in Utah, Colorado, and Oregon, before moving to Idaho. Each stop on her life’s journey included rumors of prostitution, theft, and the running of bordellos. In Aspen she was charged with “despoiling” the golden hair of a seven-year-old girl, by cutting it off. Years of morphine addiction caught up with her in 1893 and she was sent to the Keeley Institute in Forest Grove, Oregon. Upon release the now “cured” woman and her husband Harvey moved to Pendleton, where a suicide attempt landed her in the state insane asylum in Salem, later infamous itself as the setting of the Ken Kesey novel and motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest .”

After her release from that institution the Hardys moved to Moscow, Idaho, where Maggie quickly became known for a string of minor crimes and for her wicked temper.

Harvey and Maggie soon moved to Lewiston where they acquired housemates. A prostitute named Anna Meyers described by the press as “colored” lived with them, along with the woman’s toddler child, Henrietta. Harvey apparently strayed with the woman, inciting Maggie’s famous temper. Explosive as that temper could be, she took a calculated course of revenge.

Maggie made a show of reconciling with Harvey, because he was to play a part in her revenge. She talked Harvey into helping her adopt 2-year-old Henrietta. The girl’s mother did not at first consent, but ultimately put her X on a document granting custody to the Hardys. Just to Maggie Hardy, as it turned out. As soon as she got custody of Henrietta, Maggie moved back to Moscow, leaving Harvey and Anna to resume their relationship.

Within days, Maggie let it be known that she planned to poison Henrietta, then kill her mother and Harvey, and finally to commit suicide herself. Why no one intervened is unknown, though crossing the woman famous for her foul temper might have given some pause.

On Sunday, February 10, 1895 some terrible things happened. The way Maggie told it, she had prepared a large dose of morphine for herself, meaning to take her own life that way. She put that on the counter along with a glass filled with carbolic acid. It was not uncommon for people to commit suicide by swallowing carbolic acid, which would eat away the mouth, esophagus, and lungs. It was a hideous way to go.

Gosh, though, she got distracted from her suicide by something. When she returned to the room, she claimed she saw that Henrietta had found and swallowed the morphine, then tipped over the carbolic acid, spreading it all over her face though, oddly, not her hands. Henrietta was dead, her face and neck horribly disfigured and one eye eaten away.

Maggie’s story was believed by approximately no one, perhaps in part because she had earlier threatened to poison the child. Mrs. Hardy was arrested for murder.

While awaiting trial she went “suddenly stark crazy.” The sheriff figured she was angling for an insanity plea, though many who knew her thought she was never far from the mental abyss.

Hardy was charged with second degree murder because the prosecutor thought the mandatory death sentence by hanging might cause second thoughts when considering the conviction of a woman.

The jury heard arguments for a couple of days. The defense team noted that no autopsy had been done, so charging the woman with a poisoning should not hold up. They rested their case and the jury retired to deliberate. They did so all night, returning with a verdict of guilty the next morning. Maggie flew into a rage, condemning the jury, the judge, and every handy lawyer in the most vile terms.

Hoping for another outburst, the courtroom was packed on March 19 when she appeared for sentencing. To the disappointment of onlookers she sat quietly while the judge sentenced her to life in prison.

In Boise Maggie Hardy, 48, made another name for herself. Officials at the prison began calling her “Mad Margaret” because of her rages. She would howl like a wolf for days. She complained of terrible stomach pains. The pains she was experiencing, according to an inmate who travelled to the prison with her, were likely caused by here attempt to commit suicide by eating glass. Doctors saw no sign that she had done so. Her next suicide attempt was real enough. She and another inmate were being kept in a small building with side-by-side cells. The neighboring prisoner smelled smoke and began to feel heat. He yelled for help. When help arrived they found that Maggie had piled together her bed clothes and set them on fire. She was found huddled in a corner “peering through the flame and smoke, a fiendish grin on her face.”

On June 20, the superintendent of the Idaho State Insane Asylum in Blackfoot stopped by the prison to evaluate Maggie. He pronounced her “entirely sane.”

Warden John Campbell was determined to break the woman of her antics. His remedy was to build a tight, little, windowless cell for Maggie, keeping her in isolation. Seven months of such harsh treatment did little to improve Maggie’s condition, so she was shipped off to the Insane Asylum.

What happened to Maggie Hardy after that is not entirely certain. She was listed on an institution information card in Blackfoot that included the notes “Delusions of grandeur and persecution. Abnormally irritable.” Oddly, the note also included the word “dead.”

Yet, she seemed to show up one last time in the February 27, 1906 issue of the Pendelton Eastern Oregonian. The paper reported that her incinerated remains were discovered in the rubble of burned residence where she had been working as a housekeeper. When or why she was released from the asylum is lost to history’s dust.

My thanks to Steven Branting for bringing this story to my attention and sending me much information. A more detailed story about Maggie Hardy can be found in his well-written book, Wicked Lewiston .

This admission sheet, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Archives, tells a story. It's not necessarily an accurate one, according to Steven Branting, who has done a lot of research on Maggie Hardy. She was probably never a nurse, she wasn't born in Utah, and she was not illiterate. One chilling notation is that she had one child. Was that Henrietta she was reporting on?

This admission sheet, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society Archives, tells a story. It's not necessarily an accurate one, according to Steven Branting, who has done a lot of research on Maggie Hardy. She was probably never a nurse, she wasn't born in Utah, and she was not illiterate. One chilling notation is that she had one child. Was that Henrietta she was reporting on?

Published on October 12, 2018 05:00

October 11, 2018

Sockeye

That famous red fish, the sockeye has been a part of Idaho’s environment since long before man came to live here. The fish started making the newspapers early on in the state’s history. In 1899 the Idaho Statesman was reporting on the planting of sockeye eggs. Most references to sockeye salmon were in the grocery ads, starting at ten cents a can in the 1890s and rising to 59 cents for a “half-sized can” in 1956.

The Silver Blade newspaper in Rathdrum ran a report on fisheries on the Columbia August 19, 1899, that said, “The records for catching sockeye salmon were broken one day last week. At the Pacific-American Fisheries company’s cannery 136,000 were received. Of these 80,000 were sockeyes.”

That same year, the Cottonwood Report noted an estimated sockeye salmon pack of Puget Sound to 510,000 cases for the year.

The installation of dams on the Columbia and other manmade issues caused a dramatic drop in wild sockeye making their way back to Idaho. Fewer than 50 returned to Redfish Lake in 1958.

In 1991 the species was declared endangered. In 1992 a single fish, nicknamed Lonesome Larry, made it back to Redfish Lake.

The most recent ten-year average has been 690 returning to the Sawtooth Basin. In 2017 157 fish returned.

Today, the Eagle Island Fish Hatchery raises sockeye salmon near Boise in an attempt to keep the fish from going extinct.

The Silver Blade newspaper in Rathdrum ran a report on fisheries on the Columbia August 19, 1899, that said, “The records for catching sockeye salmon were broken one day last week. At the Pacific-American Fisheries company’s cannery 136,000 were received. Of these 80,000 were sockeyes.”

That same year, the Cottonwood Report noted an estimated sockeye salmon pack of Puget Sound to 510,000 cases for the year.

The installation of dams on the Columbia and other manmade issues caused a dramatic drop in wild sockeye making their way back to Idaho. Fewer than 50 returned to Redfish Lake in 1958.

In 1991 the species was declared endangered. In 1992 a single fish, nicknamed Lonesome Larry, made it back to Redfish Lake.

The most recent ten-year average has been 690 returning to the Sawtooth Basin. In 2017 157 fish returned.

Today, the Eagle Island Fish Hatchery raises sockeye salmon near Boise in an attempt to keep the fish from going extinct.

Published on October 11, 2018 04:30

October 10, 2018

Airmarkers

Most highways in Idaho have regular markers to alert you to speed limits, impending crashes if you fail to stop, and the mileage to the next three towns. That’s all very handy, but what if you’re commuting by air? Nowadays, with sophisticated navigational equipment, getting around in an airplane is something akin to that map app on your phone that speaks to you in a calm voice while you yell at it. In earlier days of airplanes, getting around was done more by seat of the pants, a cliché which owes its existence to flying.

A pilot could easily get a bit off course and think that town below her was Rigby, when it was really Rexburg. So, airmarking was invented. In 1934, Phoebe F. Omlie, Special Assistant for Air Intelligence of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, convinced the Bureau of Air Commerce to start a program whereby each state would mark their towns and cities so they could be seen from the air. Note that there is an additional hierarchy of names and acronyms associated with the program from which I’ve just saved you. You’re welcome.

Note, too, that our fictional pilot trying to discern Rigby from Rexburg in the example above was female. That’s a little nod to the fact that the airmarking project was the first US government program “conceived, planned, and directed by a woman with an all-woman staff,” according to the website of the Ninety-Nines, the leading organization of woman pilots.

The idea was to paint the name of a town on the roof of a building in bright yellow paint, outlined in black. Idaho participated in the program, but before we get to that I want to point out that it was successful. Too successful. When WWII came along officials determined that it was not such a good idea to provide enemy bombers with a “you are here” locater. The program quickly switched from painting town names on warehouse roofs, to painting over town names on warehouse roofs, at least in coastal states. After the war the paint switched from black back to yellow.

Every town in Idaho that had a roof big enough for letters got its 20-foot-high sign. Typically the State Department of Aeronautics hired a college crew during the summer to paint the whole state every five years or so. In 1963 they began dividing the state into three regions and doing one region a year.

In addition to the town name, a symbol pointed to the nearest airport and a numeral indicated how far away it was. Some symbols pointed to a couple of nearby airports.

The state no longer runs the program, but as recently as 2005 the Idaho Chapter of the Ninety-Nines was keeping some of the rooftop signs in good repair.

A related project, accomplished in conjunction with the Forest Service, marked every Forest Service lookout in Idaho with a number, again to provide pilots with navigational aids. In 1963, Kenneth Dougal, a college student from Boise, was contracted to paint every lookout in Idaho north of the Salmon river. That meant driving a panel truck to the top of a mountain, slapping on some big numbers, and winding his way down the mountain toward the next lookout. He managed to paint 110 loockouts and microwave tower buildings. To do so he flew 160 miles by helicopter, rode a horse 92 miles, walked 75 miles, rode a tote-goat (an early, not very sophisticated off highway motorbike) 45 miles, and drove the panel truck 8,000 miles. That little tidbit is courtesy of the October 1963 Rudder Flutter, the official publication of the Idaho Department of Aeronautics.

That department is now the Division of Aeronautics in the Idaho Department of Transportation. My thanks to Airport Planning and Development Manager Bill Statham and Administrative Assistant Tammy Schoen for providing me with a wealth of information on this subject.

Here's the airmarker for Spirit Lake in the late 40s. Photo courtesy of the ITD Historical Photo Collection.

Here's the airmarker for Spirit Lake in the late 40s. Photo courtesy of the ITD Historical Photo Collection.  This is a contemporary shot of the Firth airmarker, courtesy of Google Maps. It looks like the F might have made way for a new grain storage container.

This is a contemporary shot of the Firth airmarker, courtesy of Google Maps. It looks like the F might have made way for a new grain storage container.  Painting the Forest Service lookout Sourdough Station. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Painting the Forest Service lookout Sourdough Station. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

A pilot could easily get a bit off course and think that town below her was Rigby, when it was really Rexburg. So, airmarking was invented. In 1934, Phoebe F. Omlie, Special Assistant for Air Intelligence of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, convinced the Bureau of Air Commerce to start a program whereby each state would mark their towns and cities so they could be seen from the air. Note that there is an additional hierarchy of names and acronyms associated with the program from which I’ve just saved you. You’re welcome.

Note, too, that our fictional pilot trying to discern Rigby from Rexburg in the example above was female. That’s a little nod to the fact that the airmarking project was the first US government program “conceived, planned, and directed by a woman with an all-woman staff,” according to the website of the Ninety-Nines, the leading organization of woman pilots.

The idea was to paint the name of a town on the roof of a building in bright yellow paint, outlined in black. Idaho participated in the program, but before we get to that I want to point out that it was successful. Too successful. When WWII came along officials determined that it was not such a good idea to provide enemy bombers with a “you are here” locater. The program quickly switched from painting town names on warehouse roofs, to painting over town names on warehouse roofs, at least in coastal states. After the war the paint switched from black back to yellow.

Every town in Idaho that had a roof big enough for letters got its 20-foot-high sign. Typically the State Department of Aeronautics hired a college crew during the summer to paint the whole state every five years or so. In 1963 they began dividing the state into three regions and doing one region a year.

In addition to the town name, a symbol pointed to the nearest airport and a numeral indicated how far away it was. Some symbols pointed to a couple of nearby airports.

The state no longer runs the program, but as recently as 2005 the Idaho Chapter of the Ninety-Nines was keeping some of the rooftop signs in good repair.

A related project, accomplished in conjunction with the Forest Service, marked every Forest Service lookout in Idaho with a number, again to provide pilots with navigational aids. In 1963, Kenneth Dougal, a college student from Boise, was contracted to paint every lookout in Idaho north of the Salmon river. That meant driving a panel truck to the top of a mountain, slapping on some big numbers, and winding his way down the mountain toward the next lookout. He managed to paint 110 loockouts and microwave tower buildings. To do so he flew 160 miles by helicopter, rode a horse 92 miles, walked 75 miles, rode a tote-goat (an early, not very sophisticated off highway motorbike) 45 miles, and drove the panel truck 8,000 miles. That little tidbit is courtesy of the October 1963 Rudder Flutter, the official publication of the Idaho Department of Aeronautics.

That department is now the Division of Aeronautics in the Idaho Department of Transportation. My thanks to Airport Planning and Development Manager Bill Statham and Administrative Assistant Tammy Schoen for providing me with a wealth of information on this subject.

Here's the airmarker for Spirit Lake in the late 40s. Photo courtesy of the ITD Historical Photo Collection.

Here's the airmarker for Spirit Lake in the late 40s. Photo courtesy of the ITD Historical Photo Collection.  This is a contemporary shot of the Firth airmarker, courtesy of Google Maps. It looks like the F might have made way for a new grain storage container.

This is a contemporary shot of the Firth airmarker, courtesy of Google Maps. It looks like the F might have made way for a new grain storage container.  Painting the Forest Service lookout Sourdough Station. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Painting the Forest Service lookout Sourdough Station. Photo courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department digital collection.

Published on October 10, 2018 05:00

October 9, 2018

Overland Stage

Stagecoaches are an icon of Westerns. They were always getting robbed and occasionally attacked by Indians. Unlike six-gun duels in the street, which were largely an invention of dime novels, stagecoaches deserve their icon status.

The best known and most successful of the stagecoach companies was the Overland Stage. Stagecoaches brought passengers and supplies, but their most important cargo was mail. Ben Holladay, who ran the company, had the US Mail contract which brought him more than a million dollars a year for a time. He built a mansion in Washington, DC just so he could lobby Congress for contracts.

Running a stage line was profitable, but it was also expensive and complicated. Holladay had to set up stage stations every 10 to 15 miles along his routes. The one that ran through Idaho started in Kansas. The stations had vast stores of shelled corn for the horses and men to take care of the animals. The Overland Stage could boast the capability of moving along at 100 miles a day, by rolling day and night. There were frequent delays, like the ones that ended up in the movies.

Newspapers depended on the arrival of other newspapers from across the country to supplement their local editions. On August 2, 1864, the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman published a story under the standing head By Overland Stage. It explained the delay in getting news from the company by listing some of the issues coaches had run into in recent days. About 100 miles out of Denver Indians had stolen all the Overland Stage Livestock. A stage near Fort Bridger, Wyoming had also been stopped by Indians. A third stage was attacked near Platte Bridge.

The coaches were comfortable when compared with walking. All the Overland Stages were built on a standard pattern called The Concord Coach. They had heavy leather springs and were pulled by four or six horses. Passengers piled in and piled on. The company was all about profit, so they didn’t necessarily go on a schedule. They would often wait until a stage was full of people and supplies. The picture shows a stagecoach (perhaps not an Overland) on a road along the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls. It is one of the Idaho State Historical Society’s photos from the Bisbee collection.

As important as they were, stagecoaches roamed the West for a fairly short time. The Overland Stage Company, which made Holladay a fortune, lasted about ten years. Holladay transitioned to railroads, which is the way the mail went. He lost most of his fortune trying to run trains.

The best known and most successful of the stagecoach companies was the Overland Stage. Stagecoaches brought passengers and supplies, but their most important cargo was mail. Ben Holladay, who ran the company, had the US Mail contract which brought him more than a million dollars a year for a time. He built a mansion in Washington, DC just so he could lobby Congress for contracts.

Running a stage line was profitable, but it was also expensive and complicated. Holladay had to set up stage stations every 10 to 15 miles along his routes. The one that ran through Idaho started in Kansas. The stations had vast stores of shelled corn for the horses and men to take care of the animals. The Overland Stage could boast the capability of moving along at 100 miles a day, by rolling day and night. There were frequent delays, like the ones that ended up in the movies.

Newspapers depended on the arrival of other newspapers from across the country to supplement their local editions. On August 2, 1864, the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman published a story under the standing head By Overland Stage. It explained the delay in getting news from the company by listing some of the issues coaches had run into in recent days. About 100 miles out of Denver Indians had stolen all the Overland Stage Livestock. A stage near Fort Bridger, Wyoming had also been stopped by Indians. A third stage was attacked near Platte Bridge.

The coaches were comfortable when compared with walking. All the Overland Stages were built on a standard pattern called The Concord Coach. They had heavy leather springs and were pulled by four or six horses. Passengers piled in and piled on. The company was all about profit, so they didn’t necessarily go on a schedule. They would often wait until a stage was full of people and supplies. The picture shows a stagecoach (perhaps not an Overland) on a road along the Snake River Canyon near Twin Falls. It is one of the Idaho State Historical Society’s photos from the Bisbee collection.

As important as they were, stagecoaches roamed the West for a fairly short time. The Overland Stage Company, which made Holladay a fortune, lasted about ten years. Holladay transitioned to railroads, which is the way the mail went. He lost most of his fortune trying to run trains.

Published on October 09, 2018 04:30