Rick Just's Blog, page 223

September 7, 2018

State Hospital South

One of the more jarring things about searching through old newspapers is the prevalence of words commonly used at the time that have fallen out of favor today. Here’s a good example from a letter printed in the June 17, 1886 Wood River Times. The first line is, “The asylum is nearly ready for the reception of lunatics.” The letter was from T.T. Cabaniss, MD, the first administrator of what was then called the Idaho Insane Asylum, newly built and furnished in Blackfoot with $20,000 of taxpayer money.

The letter goes on to describe the facilities and makes a point that there was “not an iron bar in the house.” Even so, residents were commonly called inmates and were committed for life, albeit with the possibility of parole.

The community of Blackfoot was eager to have the facility on the outskirts of town. It meant jobs, and it gave local entrepreneurs the opportunity to bid on building materials in the early days, and the provision of supplies ongoing. Issues of the local papers in the years following the 1886 opening of the Idaho Insane Asylum were filled with advertisements to bid on providing clothing and food for the inmates. The list of needs went nearly A to Y, from “Apricots, evaporated” to “Yeast, magic.” The facility needed firewood, shoes for men and women, balls of darning cotton, coal, suspenders, buttons, and much more.

Once called the Idaho Insane Asylum, and later the South Idaho Sanitarium, the facility is today called State Hospital South. Residents are no longer called inmates, and the goal is providing effective treatment and recovery of Idaho's most seriously mentally ill citizens to enable their return to community living.

To Idaho’s credit the facility looks a bit like a college campus. It is located on 480 acres—most of which is leased for farming. State Hospital South has a $19 million annual budget with 300 full-time employees, serving an average of 115 patients at any given time.

A companion facility, State Hospital North is a 60-bed psychiatric hospital located in Orofino.

The letter goes on to describe the facilities and makes a point that there was “not an iron bar in the house.” Even so, residents were commonly called inmates and were committed for life, albeit with the possibility of parole.

The community of Blackfoot was eager to have the facility on the outskirts of town. It meant jobs, and it gave local entrepreneurs the opportunity to bid on building materials in the early days, and the provision of supplies ongoing. Issues of the local papers in the years following the 1886 opening of the Idaho Insane Asylum were filled with advertisements to bid on providing clothing and food for the inmates. The list of needs went nearly A to Y, from “Apricots, evaporated” to “Yeast, magic.” The facility needed firewood, shoes for men and women, balls of darning cotton, coal, suspenders, buttons, and much more.

Once called the Idaho Insane Asylum, and later the South Idaho Sanitarium, the facility is today called State Hospital South. Residents are no longer called inmates, and the goal is providing effective treatment and recovery of Idaho's most seriously mentally ill citizens to enable their return to community living.

To Idaho’s credit the facility looks a bit like a college campus. It is located on 480 acres—most of which is leased for farming. State Hospital South has a $19 million annual budget with 300 full-time employees, serving an average of 115 patients at any given time.

A companion facility, State Hospital North is a 60-bed psychiatric hospital located in Orofino.

Published on September 07, 2018 05:00

September 6, 2018

The Cabin

In the late 1930s Idaho State Forester Franklin Girard was tired of moving. His office got kicked around quite a bit, being forced to move eight times in three years. The Idaho Legislature was less worried about the inconvenience than Mr. Girard, so a solution to his office needs did not seem forthcoming. He decided to solve the problem himself.

Girard sought help from several lumber companies and the City of Boise. From the city, he acquired a little piece of property for a new office in Julia Davis Park (now separated from the rest of the park by Capitol Boulevard). From the lumber companies, he acquired lumber. The Boise-Payette Lumber Company loaned him their architect, Hans C. Humble, and two builders who specialized in log construction, Finns John Heillila and Gust Lapinoja.

He sold his vision to the lumber companies with a letter of solicitation that included the line, “The building, when completed, will be a show place and a perpetual advertisement for the lumber industry of Idaho.”

The Idaho State Forester’s building would showcase that lumber by featuring different Idaho wood products, and intricate wooden ceiling patterns unique to each room (see second photo). The logs for the building are peeled, round Idaho Englemahn Spruce. Inside you’ll find yellow pine, white pine, Idaho red fir, and western red cedar. Idaho doesn’t grow a lot of hardwood, so the floors are of maple from out of state. The grounds originally featured sumac, syringa, aspen, wild honeysuckle, and wild rose, all native plants.

Girard spent only $1,600 of taxpayer money for the (at the time) $40,000 building. It was completed in 1940, helping to celebrate the state’s 50th anniversary.

The building was still in use by the Idaho Department of Lands and the Soil Conservation Service until 1990. The City of Boise acquired it in 1992. In 1996, the building became the Log Cabin Literary Center.

Today the site is called simply The Cabin, and the literary organization of the same name is thriving. But the building’s future is in doubt. Oh, it’s a valued building and is in no danger of being torn down, but the design for the new Boise City Library may mean the building will need to be moved across the street and into another section of Julia Davis Park. Preservation Idaho is opposing the move. A decision on whether to move the beloved building has not yet been made. What’s your opinion?

Girard sought help from several lumber companies and the City of Boise. From the city, he acquired a little piece of property for a new office in Julia Davis Park (now separated from the rest of the park by Capitol Boulevard). From the lumber companies, he acquired lumber. The Boise-Payette Lumber Company loaned him their architect, Hans C. Humble, and two builders who specialized in log construction, Finns John Heillila and Gust Lapinoja.

He sold his vision to the lumber companies with a letter of solicitation that included the line, “The building, when completed, will be a show place and a perpetual advertisement for the lumber industry of Idaho.”

The Idaho State Forester’s building would showcase that lumber by featuring different Idaho wood products, and intricate wooden ceiling patterns unique to each room (see second photo). The logs for the building are peeled, round Idaho Englemahn Spruce. Inside you’ll find yellow pine, white pine, Idaho red fir, and western red cedar. Idaho doesn’t grow a lot of hardwood, so the floors are of maple from out of state. The grounds originally featured sumac, syringa, aspen, wild honeysuckle, and wild rose, all native plants.

Girard spent only $1,600 of taxpayer money for the (at the time) $40,000 building. It was completed in 1940, helping to celebrate the state’s 50th anniversary.

The building was still in use by the Idaho Department of Lands and the Soil Conservation Service until 1990. The City of Boise acquired it in 1992. In 1996, the building became the Log Cabin Literary Center.

Today the site is called simply The Cabin, and the literary organization of the same name is thriving. But the building’s future is in doubt. Oh, it’s a valued building and is in no danger of being torn down, but the design for the new Boise City Library may mean the building will need to be moved across the street and into another section of Julia Davis Park. Preservation Idaho is opposing the move. A decision on whether to move the beloved building has not yet been made. What’s your opinion?

Published on September 06, 2018 05:00

September 5, 2018

Idaho's Sinking Farm

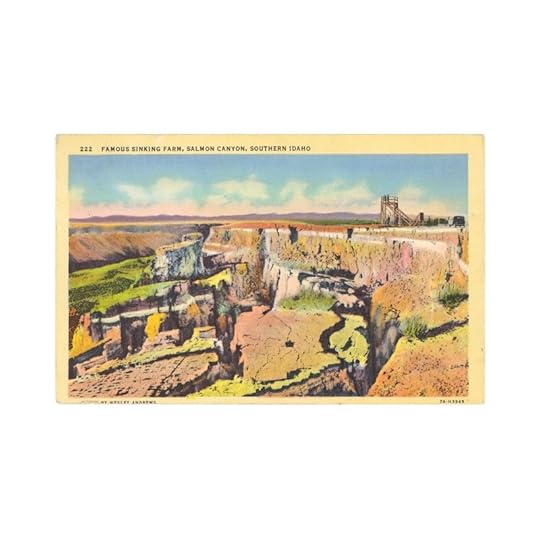

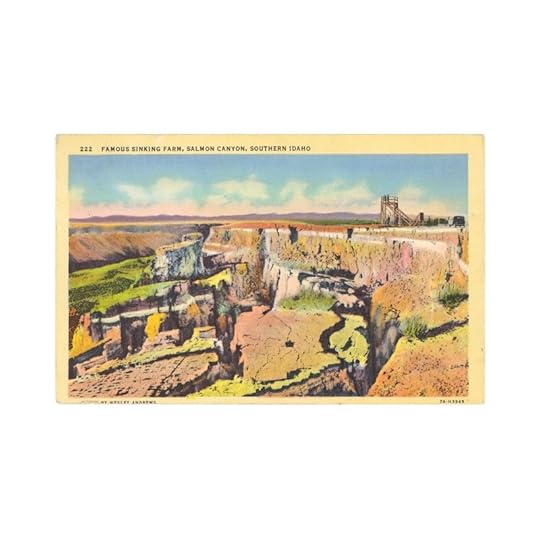

Buhl doesn't get in the news much, which is probably the way the residents like it. In 1937, though, there was national attention on a farm near there. It was dubbed “the sinking farm” in newspaper headlines. Hundreds of tourists flocked to the area and Buhl residents began hiring themselves out as guides. They even started selling picture postcards (photo below) of the event.

The farm was on the rim overlooking Salmon Falls Creek Canyon. Strictly speaking, the farm wasn’t so much sinking as it was falling into the canyon as erosion undercut the foundations of the canyon wall. The wall was breaking off in huge chunks like a glacier calving. Some rock would fall into the canyon and big chunks of it would sink and break and shift, making the land on top of it less than favorable for farming.

Paramount News was there to capture the event on film for newsreels. Geologists from local universities were also on hand to view the phenomenon and explain things to reporters.

Newspaper reports sometimes called it the H.A. Robertson farm. But other reports claimed it was Dr. C. C. Griffith who owned 320 acres on the canyon rim. He was away at his summer house in New York when all the excitement happened. According to a dispatch from the New York Herald-Tribune, which ran in the August 28, 1937, edition of the Idaho Statesman, he wasn’t worried about losing a few acres to the canyon. “What worries him most is the hazard the public is running invading his property.” His ranch manager, Emil Bordewick, was apoplectic about the crowds of people coming to the ranch. There was a deputy on site who wasn’t arresting anyone because wholesale arrests for trespassing might “cause a lot of trouble.” Bordewick had hired a guard. He had informed his employer it would cost $500 a month to “keep these people from getting killed.” And by the way, he wanted a raise.

Meanwhile, experts from the United States Geological Survey were not in a panic. They predicted the sinking would go on for a while. About five million years.

The grumpy ranch manager did see one potential silver lining. Well, a gold lining. He was hoping the new fissures in the earth might reveal a vein of gold.

The farm was on the rim overlooking Salmon Falls Creek Canyon. Strictly speaking, the farm wasn’t so much sinking as it was falling into the canyon as erosion undercut the foundations of the canyon wall. The wall was breaking off in huge chunks like a glacier calving. Some rock would fall into the canyon and big chunks of it would sink and break and shift, making the land on top of it less than favorable for farming.

Paramount News was there to capture the event on film for newsreels. Geologists from local universities were also on hand to view the phenomenon and explain things to reporters.

Newspaper reports sometimes called it the H.A. Robertson farm. But other reports claimed it was Dr. C. C. Griffith who owned 320 acres on the canyon rim. He was away at his summer house in New York when all the excitement happened. According to a dispatch from the New York Herald-Tribune, which ran in the August 28, 1937, edition of the Idaho Statesman, he wasn’t worried about losing a few acres to the canyon. “What worries him most is the hazard the public is running invading his property.” His ranch manager, Emil Bordewick, was apoplectic about the crowds of people coming to the ranch. There was a deputy on site who wasn’t arresting anyone because wholesale arrests for trespassing might “cause a lot of trouble.” Bordewick had hired a guard. He had informed his employer it would cost $500 a month to “keep these people from getting killed.” And by the way, he wanted a raise.

Meanwhile, experts from the United States Geological Survey were not in a panic. They predicted the sinking would go on for a while. About five million years.

The grumpy ranch manager did see one potential silver lining. Well, a gold lining. He was hoping the new fissures in the earth might reveal a vein of gold.

Published on September 05, 2018 05:00

September 4, 2018

Doc Yandell's Claim

We often think of early settlers as homesteaders. In Idaho, that’s mostly the case, because the Homestead Act of 1862 opened up thousands of acres for agricultural development just as the territory was taking shape. Even before that, there was an option for formally claiming land. The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 allowed settlers to claim 320 or 640 acres in Oregon Territory, which included present-day Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and some of what is now Wyoming. The act expired in 1855.

One very early settler missed at least two chances, then, to make his claim to land along the Portneuf River near present-day Pocatello official. He ignored both acts, possibly because he never heard about them or, as he claimed, because he was certain the land was his already, courtesy of the Queen of England.

In 1911, this letter appeared in the Pocatello Tribune.

"I wish to state that in the year 1852, I located in the Snake River valley and purchased two tracts of land from the Hudson Bay Fur Co. I have occupied and claimed this land since that time. My children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were all born on this land, and I supposed I had a perfect title to the land by the papers given me from the Hudson Bay Fur Co. That company gave me the right to the land in the name of her majesty, Queen Victoria of England. And now comes an allotting agent from the Bureau of Indian Affairs who claims I have no rights to the above stated land, and has commenced to allot my lands to the Indians.

"At the time I located here it was wild, unsettled Indian country from the state of Missouri to the Pacific coast. The United States did not own this country at that time. When England ceded this territory to the United States, the treaty read that those who remained here should have all the rights of American citizens (which is not saying much for American citizens). What motive they now have for taking my land away from me, which I have owned for over 60 years, and give it to strangers, is for revenue only. I will leave in a few weeks for Winnipeg, Manitoba, where I will secure all necessary papers from the Hudson Bay Fur Co., which will show that I have perfect right to the lands which I have occupied for years.

"These lands have been playgrounds for picnic parties every year since I have lived here, and I wish to still hold it and everybody at any time is perfectly welcome to camp there and enjoy themselves, which has been the custom for many years."

The letter was signed “Doc Yandell.”

Issac M. “Doc” Yandell was well known to local people who knew him as one of the “old timers” who lived where Pocatello would be long before the town came along in 1889. He kept some of the land he claimed as something of a community park, inviting all who wished to picnic and recreate there.

His claim of ownership to the land was never proved before his death in 1916 at about age 87. Oregon Territory was created in 1848, four years before Doc Yandell said he purchased the land from the Hudson Bay Company. The law in that new country at the time was a little iffy and mechanisms for enforcement nearly nonexistent. Whether or not he had a legitimate claim to the land is a question that is probably unanswerable today. He may have had good reason to believe the land was his.

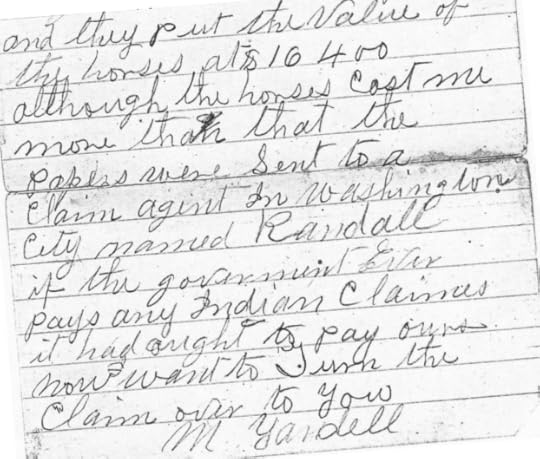

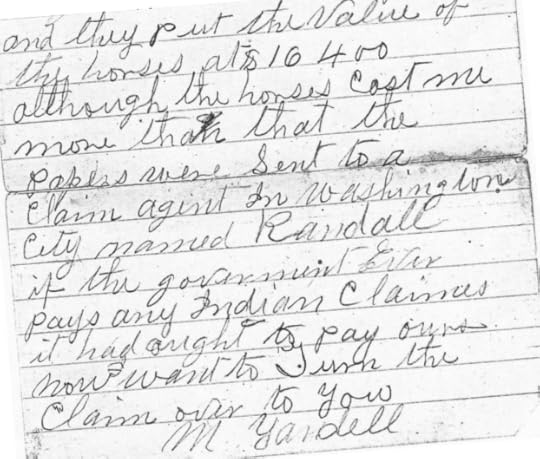

Yandell had another beef with the U.S. government. His letters show that he was making a claim for a herd of horses he said had been stolen by the Nez Perce during their 1877 flight across the West. He was claiming a loss of $16,400 for the horses. The government was paying for some claims that came about as a result of that running battle. Whether Doc Yandell was ever reimbursed is unknown, at least by me.

Thanks to Theresa Orison, a descendant, for providing clippings and letters about and from Doc Yandell.

One very early settler missed at least two chances, then, to make his claim to land along the Portneuf River near present-day Pocatello official. He ignored both acts, possibly because he never heard about them or, as he claimed, because he was certain the land was his already, courtesy of the Queen of England.

In 1911, this letter appeared in the Pocatello Tribune.

"I wish to state that in the year 1852, I located in the Snake River valley and purchased two tracts of land from the Hudson Bay Fur Co. I have occupied and claimed this land since that time. My children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren were all born on this land, and I supposed I had a perfect title to the land by the papers given me from the Hudson Bay Fur Co. That company gave me the right to the land in the name of her majesty, Queen Victoria of England. And now comes an allotting agent from the Bureau of Indian Affairs who claims I have no rights to the above stated land, and has commenced to allot my lands to the Indians.

"At the time I located here it was wild, unsettled Indian country from the state of Missouri to the Pacific coast. The United States did not own this country at that time. When England ceded this territory to the United States, the treaty read that those who remained here should have all the rights of American citizens (which is not saying much for American citizens). What motive they now have for taking my land away from me, which I have owned for over 60 years, and give it to strangers, is for revenue only. I will leave in a few weeks for Winnipeg, Manitoba, where I will secure all necessary papers from the Hudson Bay Fur Co., which will show that I have perfect right to the lands which I have occupied for years.

"These lands have been playgrounds for picnic parties every year since I have lived here, and I wish to still hold it and everybody at any time is perfectly welcome to camp there and enjoy themselves, which has been the custom for many years."

The letter was signed “Doc Yandell.”

Issac M. “Doc” Yandell was well known to local people who knew him as one of the “old timers” who lived where Pocatello would be long before the town came along in 1889. He kept some of the land he claimed as something of a community park, inviting all who wished to picnic and recreate there.

His claim of ownership to the land was never proved before his death in 1916 at about age 87. Oregon Territory was created in 1848, four years before Doc Yandell said he purchased the land from the Hudson Bay Company. The law in that new country at the time was a little iffy and mechanisms for enforcement nearly nonexistent. Whether or not he had a legitimate claim to the land is a question that is probably unanswerable today. He may have had good reason to believe the land was his.

Yandell had another beef with the U.S. government. His letters show that he was making a claim for a herd of horses he said had been stolen by the Nez Perce during their 1877 flight across the West. He was claiming a loss of $16,400 for the horses. The government was paying for some claims that came about as a result of that running battle. Whether Doc Yandell was ever reimbursed is unknown, at least by me.

Thanks to Theresa Orison, a descendant, for providing clippings and letters about and from Doc Yandell.

Published on September 04, 2018 05:00

September 3, 2018

Idaho Connections to the Great San Francisco Earthquake

Idaho history often includes events that took place out of state, but which impacted Idaho residents. One such event was the earthquake that hit San Francisco on April 18, 1906. Just five days later the Idaho Daily Statesman compiled a list of what communities where doing and the funds they had already raised for San Francisco relief.

Boise had raised $8,258.50. Caldwell, Paris, Genessee, and Lewiston had each shipped a car of flour. Payette was arranging for “a large amount of food (to be) cooked and shipped no later than tomorrow evening. It is the plan to buy out the remaining stock of canned goods of the cannery and ship it.”

The Commercial Club in Mountain Home had raise $100 and the city had matched it. The Commercial Club in Hailey raise $321.75 in an hour and a half. Blackfoot had raised $100 so far. Cambridge was ready to contribute $71.50. Sugar City had raised $250. Montpelier contributed $180.

Lewiston had already raised $2,000 with a goal of $3,000. Sandpoint was planning a ball to raise money. Coeur d’Alene had raised $300 and was putting on a benefit minstrel show. Moscow had sent a car of supplies and was planning to send more.

The CPI inflation calculator goes back only to 1913. Using that year as a base, $100 in 1906 was about the equivalent of $2500 today. Just the dollars reported on that fifth day after the earthquake would be nearly $300,000 in today’s dollars. Idaho at that time had about 165,000 residents.

The generosity of Idahoans is laudable. It’s worth noting that the earthquake brought something special to the state. For a few weeks Riverside Park in Boise hosted the San Francisco Opera Company. How special was it? The Idaho Statesman reported that “Never until the earthquake in April could the old Tivoli company be induced to leave San Francisco. But after that catastrophe, it was recognized that there would be no room for amusements in the stricken city for many months, and the members of the company, some of whom had been playing at the historic old playhouse for many years, left the California metropolis with many fears and misgivings, all hoping that the time of their banishment might be short.”

Riverside Park paid the company $2,000 a week while they were in town. Perhaps they made some money from the engagement. There was no shortage of efforts to make a buck off the disaster. Dozens of advertisements looking for agents to sell copies of competing books about the disaster began appearing on April 27 and continued for weeks. One local ad in Boise offered six carloads of pianos that had been enroute to San Francisco that were to be “sacrificed” for $187 to $327. “Suffice it to say that no combination of circumstances has ever brought piano prices so low as appear on our price tags now.” What good luck!

Boise had raised $8,258.50. Caldwell, Paris, Genessee, and Lewiston had each shipped a car of flour. Payette was arranging for “a large amount of food (to be) cooked and shipped no later than tomorrow evening. It is the plan to buy out the remaining stock of canned goods of the cannery and ship it.”

The Commercial Club in Mountain Home had raise $100 and the city had matched it. The Commercial Club in Hailey raise $321.75 in an hour and a half. Blackfoot had raised $100 so far. Cambridge was ready to contribute $71.50. Sugar City had raised $250. Montpelier contributed $180.

Lewiston had already raised $2,000 with a goal of $3,000. Sandpoint was planning a ball to raise money. Coeur d’Alene had raised $300 and was putting on a benefit minstrel show. Moscow had sent a car of supplies and was planning to send more.

The CPI inflation calculator goes back only to 1913. Using that year as a base, $100 in 1906 was about the equivalent of $2500 today. Just the dollars reported on that fifth day after the earthquake would be nearly $300,000 in today’s dollars. Idaho at that time had about 165,000 residents.

The generosity of Idahoans is laudable. It’s worth noting that the earthquake brought something special to the state. For a few weeks Riverside Park in Boise hosted the San Francisco Opera Company. How special was it? The Idaho Statesman reported that “Never until the earthquake in April could the old Tivoli company be induced to leave San Francisco. But after that catastrophe, it was recognized that there would be no room for amusements in the stricken city for many months, and the members of the company, some of whom had been playing at the historic old playhouse for many years, left the California metropolis with many fears and misgivings, all hoping that the time of their banishment might be short.”

Riverside Park paid the company $2,000 a week while they were in town. Perhaps they made some money from the engagement. There was no shortage of efforts to make a buck off the disaster. Dozens of advertisements looking for agents to sell copies of competing books about the disaster began appearing on April 27 and continued for weeks. One local ad in Boise offered six carloads of pianos that had been enroute to San Francisco that were to be “sacrificed” for $187 to $327. “Suffice it to say that no combination of circumstances has ever brought piano prices so low as appear on our price tags now.” What good luck!

Published on September 03, 2018 05:00

September 2, 2018

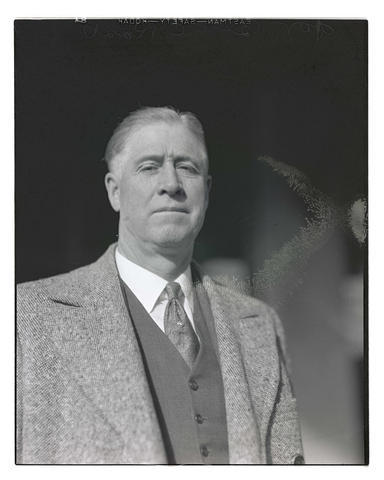

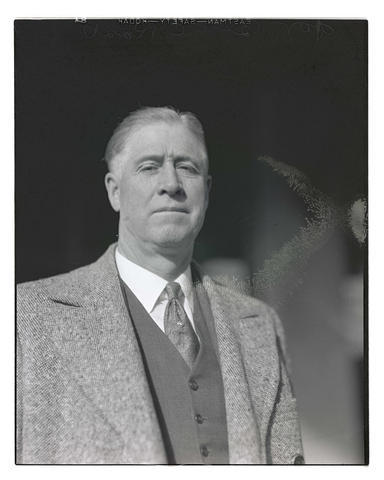

C. Ben Ross

The C. in C. Ben Ross’ name did not stand for Cowboy. His first name was Charles. But he was known as “Cowboy Ben” for most of his life.

Idaho’s first native born governor grew up on the family ranch near Parma, herding cows and riding horses with other cowboys until he was 18. As much as he loved being a cowboy his sights were set on the statehouse, even as a boy. He would often joke with the hands that they should be proud to be riding with Idaho’s future governor.

Ross went through the sixth grade in Parma, then at 18 he attended business school in Portland and took business classes in Boise. With three years of higher education behind him, C. Ben returned to the ranch in 1897, where he and his brother, W.H. Ross became prominent farmers and stockmen.

Politics never ceased calling to him. He ran for Canyon County commissioner in 1915 and won the seat, running as “the farmers’ friend.” The slogan he used was “The Cow, The Pig, and The Hen.” He held that office until 1921 when he and his family moved to Bannock County to work land he had purchased in the Michaud Flats irrigation district. By that time he had become well-known across the state as one of the founders of the Idaho Farm Bureau. That may account for his astonishingly quick success in politics in his new hometown. He was elected mayor of Pocatello less than two years after moving there.

The mayor brought paved streets and an improved water system to the city, serving as mayor for three terms. He took his first shot at the statehouse in 1928, but was defeated by an old friend from Parma, H.C. Baldridge.

Ross was back running for governor in 1930. This time he took the statehouse. He would be the first Idaho governor to be elected three times in a row, though it should be noted that gubernatorial terms then were just two years.

In 1936 Ross decided to take on popular US Senator William E. Borah. Borah soundly defeated him and “Cowboy Ben” vowed to quit politics. That vow lasted until 1938 when he decided to run for governor again to clear his name. Political foes had called for a special audit of his Bureau of Highways, and he wanted to be vindicated. He won the race in the Democratic primary, but ultimately lost to Republican C.A. Bottolfsen, questions about his past administrative practices dragging him down.

C. Ben Ross retired to his place in Parma where he was struck down by a heart attack in 1939.

Much of the information for this post came from an article by Michael J. Malone in the Winter 1966-1967 Idaho Yesterdays.

Idaho’s first native born governor grew up on the family ranch near Parma, herding cows and riding horses with other cowboys until he was 18. As much as he loved being a cowboy his sights were set on the statehouse, even as a boy. He would often joke with the hands that they should be proud to be riding with Idaho’s future governor.

Ross went through the sixth grade in Parma, then at 18 he attended business school in Portland and took business classes in Boise. With three years of higher education behind him, C. Ben returned to the ranch in 1897, where he and his brother, W.H. Ross became prominent farmers and stockmen.

Politics never ceased calling to him. He ran for Canyon County commissioner in 1915 and won the seat, running as “the farmers’ friend.” The slogan he used was “The Cow, The Pig, and The Hen.” He held that office until 1921 when he and his family moved to Bannock County to work land he had purchased in the Michaud Flats irrigation district. By that time he had become well-known across the state as one of the founders of the Idaho Farm Bureau. That may account for his astonishingly quick success in politics in his new hometown. He was elected mayor of Pocatello less than two years after moving there.

The mayor brought paved streets and an improved water system to the city, serving as mayor for three terms. He took his first shot at the statehouse in 1928, but was defeated by an old friend from Parma, H.C. Baldridge.

Ross was back running for governor in 1930. This time he took the statehouse. He would be the first Idaho governor to be elected three times in a row, though it should be noted that gubernatorial terms then were just two years.

In 1936 Ross decided to take on popular US Senator William E. Borah. Borah soundly defeated him and “Cowboy Ben” vowed to quit politics. That vow lasted until 1938 when he decided to run for governor again to clear his name. Political foes had called for a special audit of his Bureau of Highways, and he wanted to be vindicated. He won the race in the Democratic primary, but ultimately lost to Republican C.A. Bottolfsen, questions about his past administrative practices dragging him down.

C. Ben Ross retired to his place in Parma where he was struck down by a heart attack in 1939.

Much of the information for this post came from an article by Michael J. Malone in the Winter 1966-1967 Idaho Yesterdays.

Published on September 02, 2018 05:00

September 1, 2018

Pocatello

To say that the city of Pocatello is named after Chief Pocatello is correct. Yet, those two words, chief and Pocatello, are themselves subject to much disagreement.

The concept of “chief” was often one introduced to Native American tribes by white settlers and soldiers. Soldiers, especially, liked the supposed certainty of dealing with a single person who could speak for a tribe. The tribes themselves often held several members—often elders—in high esteem because of their various skills or wisdom. The fact that a certain chief would sign a treaty did not always mean he spoke for his tribe in doing so.

Pocatello was certainly a trusted leader of his band of Shoshonis. Most such leaders, according to historian Merle Wells, considered themselves equals. Circumstances brought on by the influx of settlers into traditional Shoshoni lands, however, made Pocatello “more equal among equals.”

There is more confusion about his name than about his rank. The name has been given several meanings over the years. Brigham D. Madsen, in his book Chief Pocatello points to the first mention of the man in the 1857 writings of an Indian agent who called him “Koctallo.” Two years later an army officer who had never met him, but had often heard his name, wrote it as “Pocataro.” Some insist that the meaning of the name is something like “he who does not take the trail” or “in the middle of the road.” Others say it may have come from the town in Georgia called Pocataligo, which may be a Yamasee or Cherokee Indian word, the meaning of which is also in dispute. Note that residents of Pocatligo often call the place “Pokey” for short, just as the residents of Pocatello do. In any case, the Georgia connection seems far-fetched.

So the whites are confused. What about his own people? Again according to Madsen, the Hukandeka Shoshoni called him Tonaioza, meaning “Buffalo Robe,” or sometimes Kanah, which is apparently a reference to the gift of an army coat given to him by Gen. Patrick E. Connor during the signing of the Treaty of Box Elder. According to his daughter, Jeanette Pocatello Lewis, Pocatello never used that name at all and always went by Tonaioza or Tondzaosha.

One popular explanation for the name still heard is that the man was well known for his love of pork and tallow. Get it? Porkantallow? One must—if one is me, at least—call BS on that one. Under what circumstances would one particularly desire those two items to the extent that he would be named for them? It seems an obvious backformation meant to belittle a man who in no way deserved it.

There is much more to tell about this historical figure. We will leave that for future posts.

The photo is a depiction of Chief Pocatello, a travertine statue installed in 2008 at the Pocatello visitor center, and sculpted by J.D. Adcox.

The concept of “chief” was often one introduced to Native American tribes by white settlers and soldiers. Soldiers, especially, liked the supposed certainty of dealing with a single person who could speak for a tribe. The tribes themselves often held several members—often elders—in high esteem because of their various skills or wisdom. The fact that a certain chief would sign a treaty did not always mean he spoke for his tribe in doing so.

Pocatello was certainly a trusted leader of his band of Shoshonis. Most such leaders, according to historian Merle Wells, considered themselves equals. Circumstances brought on by the influx of settlers into traditional Shoshoni lands, however, made Pocatello “more equal among equals.”

There is more confusion about his name than about his rank. The name has been given several meanings over the years. Brigham D. Madsen, in his book Chief Pocatello points to the first mention of the man in the 1857 writings of an Indian agent who called him “Koctallo.” Two years later an army officer who had never met him, but had often heard his name, wrote it as “Pocataro.” Some insist that the meaning of the name is something like “he who does not take the trail” or “in the middle of the road.” Others say it may have come from the town in Georgia called Pocataligo, which may be a Yamasee or Cherokee Indian word, the meaning of which is also in dispute. Note that residents of Pocatligo often call the place “Pokey” for short, just as the residents of Pocatello do. In any case, the Georgia connection seems far-fetched.

So the whites are confused. What about his own people? Again according to Madsen, the Hukandeka Shoshoni called him Tonaioza, meaning “Buffalo Robe,” or sometimes Kanah, which is apparently a reference to the gift of an army coat given to him by Gen. Patrick E. Connor during the signing of the Treaty of Box Elder. According to his daughter, Jeanette Pocatello Lewis, Pocatello never used that name at all and always went by Tonaioza or Tondzaosha.

One popular explanation for the name still heard is that the man was well known for his love of pork and tallow. Get it? Porkantallow? One must—if one is me, at least—call BS on that one. Under what circumstances would one particularly desire those two items to the extent that he would be named for them? It seems an obvious backformation meant to belittle a man who in no way deserved it.

There is much more to tell about this historical figure. We will leave that for future posts.

The photo is a depiction of Chief Pocatello, a travertine statue installed in 2008 at the Pocatello visitor center, and sculpted by J.D. Adcox.

Published on September 01, 2018 05:00

August 31, 2018

Big Mike

One of the most common locomotive engines during the heyday of steam was the Mikado. It was called the Mikado because many of the first engines were built for export to Japan. Railroad workers nicknamed the Mikados “Mike.” That’s why the one on display at the Boise Depot is called Big Mike.

They were giants. Big Mike is almost 82 feet long, counting its tender. It’s 15 feet 10 3/8 inches from the ground to the top of the stack, and the whole thing weighs 463,000 pounds before it takes on up to 17 tons of coal and 10,000 gallons of water.

They built the 14,000 Mikados from 1911 through 1944. Big Mike is a Mikado 282, which means it has eight big wheels underneath the locomotive with two smaller wheels in front and two in back.

Big Mike, or Engine No. 2295, was retired by Union Pacific and donated to the city of Boise in 1956. The locomotive was subsequently moved to the 3rd Street entrance to Julia Davis Park.

On Dec. 9, 2007, Big Mike—minus its tender—was moved to a new home on a siding east of the Boise Depot. Hundreds of people watched the move, which occurred at midnight on a cold winter's night. The tender, which carried water and fuel for the engine, was separated from the engine and had been moved on Dec. 6, 2007.

It’s well worth visiting the Boise Depot and Big Mike if you haven’t already done so.

They were giants. Big Mike is almost 82 feet long, counting its tender. It’s 15 feet 10 3/8 inches from the ground to the top of the stack, and the whole thing weighs 463,000 pounds before it takes on up to 17 tons of coal and 10,000 gallons of water.

They built the 14,000 Mikados from 1911 through 1944. Big Mike is a Mikado 282, which means it has eight big wheels underneath the locomotive with two smaller wheels in front and two in back.

Big Mike, or Engine No. 2295, was retired by Union Pacific and donated to the city of Boise in 1956. The locomotive was subsequently moved to the 3rd Street entrance to Julia Davis Park.

On Dec. 9, 2007, Big Mike—minus its tender—was moved to a new home on a siding east of the Boise Depot. Hundreds of people watched the move, which occurred at midnight on a cold winter's night. The tender, which carried water and fuel for the engine, was separated from the engine and had been moved on Dec. 6, 2007.

It’s well worth visiting the Boise Depot and Big Mike if you haven’t already done so.

Published on August 31, 2018 05:00

August 30, 2018

These are not the tribes you are thinking of

Sometimes it helps to know the history of a thing. Such is the case with the Improved Order of Red Men. The July 7, 1906 edition of the Idaho Daily Statesman featured a two-column article headlined, “Red Men of Gem State Gather in Capital City.” The subhead was, “First Great Council in Idaho to be Formed by Delegates of Tribes Today.”

Well, that piqued my interest. Could this be an actual meeting of Native American Tribes calling themselves Red Men? I thought not, particularly when I noticed the photos of two of the attendees not in native regalia, but in formal wear.

The article began, “Boise is now in the hands of Red Men. The braves have come from every direction, pouring into the city until it was no use to longer resist them. But unlike the red men of old, they came announced and Boise gracefully surrenders to them.”

The piece went on to call out “tribes” whose names I had never heard associated with Idaho, Incohonnee, How-Lish-Whampa, and Tillicum. The Great Chief of Records was expected to attend.

Okay, I had to find out more about what was clearly a fraternal organization with some—no, many, elements that are cringe-worthy to ears more attuned to what would likely offend Native Americans today. Witness: Local units are called Tribes, local meeting sites are Wigwams, the state level of the organization is called the Reservation, presided over by a board of Chiefs. Their youth auxiliary for males is the Degree of Hiawatha, and the female auxiliary is the Degree of Pocahontas.

Note that I used present tense in the above paragraph. That’s because the Improved Order of Red Men still exists. Today there are about 15,000 members nationwide. When the 1906 article about their convention in Boise came out, it was noted that 435,000 “braves” were expected at the national convention of the group.

They have a history, of course, and you know some of it. The group’s roots go back to the Boston Tea Party. Remember that? Men unhappy with taxes dressed up as Indians to toss tea into the harbor. There were name changes and consolidations over the years, but that was the beginning of the group. And, you’ve probably heard of something else in history that you had no idea (at least I had no idea) that a fraternal organization was responsible for. This group organized the famous, and ultimately infamous, political machine known as Tammany Hall in New York City.

The Wikipedia entry on the Red Men includes a picture of Red Men’s Hall in Jacksonville, Oregon, established in 1884.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Improved_Order_of_Red_Men

The image accompanying this post is from the aforementioned Statesman article from 1906. As a side note, I was researching Idaho’s reaction to the San Francisco earthquake of that year for a couple of future posts when I came across what to me was an interesting oddity. So, my distraction is now your distraction. You’re welcome.

Well, that piqued my interest. Could this be an actual meeting of Native American Tribes calling themselves Red Men? I thought not, particularly when I noticed the photos of two of the attendees not in native regalia, but in formal wear.

The article began, “Boise is now in the hands of Red Men. The braves have come from every direction, pouring into the city until it was no use to longer resist them. But unlike the red men of old, they came announced and Boise gracefully surrenders to them.”

The piece went on to call out “tribes” whose names I had never heard associated with Idaho, Incohonnee, How-Lish-Whampa, and Tillicum. The Great Chief of Records was expected to attend.

Okay, I had to find out more about what was clearly a fraternal organization with some—no, many, elements that are cringe-worthy to ears more attuned to what would likely offend Native Americans today. Witness: Local units are called Tribes, local meeting sites are Wigwams, the state level of the organization is called the Reservation, presided over by a board of Chiefs. Their youth auxiliary for males is the Degree of Hiawatha, and the female auxiliary is the Degree of Pocahontas.

Note that I used present tense in the above paragraph. That’s because the Improved Order of Red Men still exists. Today there are about 15,000 members nationwide. When the 1906 article about their convention in Boise came out, it was noted that 435,000 “braves” were expected at the national convention of the group.

They have a history, of course, and you know some of it. The group’s roots go back to the Boston Tea Party. Remember that? Men unhappy with taxes dressed up as Indians to toss tea into the harbor. There were name changes and consolidations over the years, but that was the beginning of the group. And, you’ve probably heard of something else in history that you had no idea (at least I had no idea) that a fraternal organization was responsible for. This group organized the famous, and ultimately infamous, political machine known as Tammany Hall in New York City.

The Wikipedia entry on the Red Men includes a picture of Red Men’s Hall in Jacksonville, Oregon, established in 1884.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Improved_Order_of_Red_Men

The image accompanying this post is from the aforementioned Statesman article from 1906. As a side note, I was researching Idaho’s reaction to the San Francisco earthquake of that year for a couple of future posts when I came across what to me was an interesting oddity. So, my distraction is now your distraction. You’re welcome.

Published on August 30, 2018 05:00

August 29, 2018

Film of Cataldo Mission

If you spent fourth grade in an Idaho school, you learned something about the Cataldo Mission of the Sacred Heart, Idaho’s oldest standing building. Construction started in 1850, and the mission was finished in 1853. The 1884 photograph on the left was taken more than 30 years after its completion. Even this early in its history the building is showing some wear, particularly on the entrance steps where several members of the Coeur d’Alene tribe are standing.

Below, the picture on the right shows the building in the mid 1920s. In the second photo you can see the Parish house on the left that was built after the first photo was taken. Also note the urns on the façade of the building. There are four in the earlier picture, and only two in the one on the right. Those were replaced in later reconstructions. Now, here’s a little treat for you. In 1926 the word documentary was brand new. So was a movie camera owned by one of the mines in the Silver Valley. They used it to shoot this short film below on the 75th anniversary of the building of the Cataldo Mission. The mission was in terrible shape at the time. But what makes the film so special is that Father Cataldo, the man the mission was named after, is in the film. He’s the little old priest on crutches. He did not build the mission, but it was named in his honor some years after it was built. Cataldo was one of the founders of the city of Spokane, and started Gonzaga University. #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094{ background: url(//www.weebly.com/uploads/old_mission_37... } #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094, #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } } It was Fr. Anthony Ravalli, an Italian-born priest, who designed and directed the building of the mission. The priests, and some 400 tribal members had only simple tools such as a whip saw, broad axe, augur, ropes and pulleys, and a pen knife. The flooring for the mission, the steps, and the iconic columns marking its entrance were cut from local pines. Tall wooden pillars and columns are held together by wooden pegs. No nails were used in the original construction.

Now, here’s a little treat for you. In 1926 the word documentary was brand new. So was a movie camera owned by one of the mines in the Silver Valley. They used it to shoot this short film below on the 75th anniversary of the building of the Cataldo Mission. The mission was in terrible shape at the time. But what makes the film so special is that Father Cataldo, the man the mission was named after, is in the film. He’s the little old priest on crutches. He did not build the mission, but it was named in his honor some years after it was built. Cataldo was one of the founders of the city of Spokane, and started Gonzaga University. #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094{ background: url(//www.weebly.com/uploads/old_mission_37... } #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094, #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } } It was Fr. Anthony Ravalli, an Italian-born priest, who designed and directed the building of the mission. The priests, and some 400 tribal members had only simple tools such as a whip saw, broad axe, augur, ropes and pulleys, and a pen knife. The flooring for the mission, the steps, and the iconic columns marking its entrance were cut from local pines. Tall wooden pillars and columns are held together by wooden pegs. No nails were used in the original construction.

A stone foundation holds up 30-foot-high walls made of mud, grass, and willow saplings interlaced in what is called wattle and daub construction. The building was clad with clapboard in 1865, hiding the inner walls, but park visitors can still see exposed sections on the interior, complete with fingerprints of those who worked on them. The aerial shot below of the mission today is courtesy of the Idaho Heritage Trust, which has been instrumental in many restoration projects at what is now called Coeur d’Alene’s Old Mission State Park.

Below, the picture on the right shows the building in the mid 1920s. In the second photo you can see the Parish house on the left that was built after the first photo was taken. Also note the urns on the façade of the building. There are four in the earlier picture, and only two in the one on the right. Those were replaced in later reconstructions.

Now, here’s a little treat for you. In 1926 the word documentary was brand new. So was a movie camera owned by one of the mines in the Silver Valley. They used it to shoot this short film below on the 75th anniversary of the building of the Cataldo Mission. The mission was in terrible shape at the time. But what makes the film so special is that Father Cataldo, the man the mission was named after, is in the film. He’s the little old priest on crutches. He did not build the mission, but it was named in his honor some years after it was built. Cataldo was one of the founders of the city of Spokane, and started Gonzaga University. #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094{ background: url(//www.weebly.com/uploads/old_mission_37... } #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094, #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } } It was Fr. Anthony Ravalli, an Italian-born priest, who designed and directed the building of the mission. The priests, and some 400 tribal members had only simple tools such as a whip saw, broad axe, augur, ropes and pulleys, and a pen knife. The flooring for the mission, the steps, and the iconic columns marking its entrance were cut from local pines. Tall wooden pillars and columns are held together by wooden pegs. No nails were used in the original construction.

Now, here’s a little treat for you. In 1926 the word documentary was brand new. So was a movie camera owned by one of the mines in the Silver Valley. They used it to shoot this short film below on the 75th anniversary of the building of the Cataldo Mission. The mission was in terrible shape at the time. But what makes the film so special is that Father Cataldo, the man the mission was named after, is in the film. He’s the little old priest on crutches. He did not build the mission, but it was named in his honor some years after it was built. Cataldo was one of the founders of the city of Spokane, and started Gonzaga University. #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094{ background: url(//www.weebly.com/uploads/old_mission_37... } #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-375230924329529094, #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-375230924329529094{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } } It was Fr. Anthony Ravalli, an Italian-born priest, who designed and directed the building of the mission. The priests, and some 400 tribal members had only simple tools such as a whip saw, broad axe, augur, ropes and pulleys, and a pen knife. The flooring for the mission, the steps, and the iconic columns marking its entrance were cut from local pines. Tall wooden pillars and columns are held together by wooden pegs. No nails were used in the original construction.A stone foundation holds up 30-foot-high walls made of mud, grass, and willow saplings interlaced in what is called wattle and daub construction. The building was clad with clapboard in 1865, hiding the inner walls, but park visitors can still see exposed sections on the interior, complete with fingerprints of those who worked on them. The aerial shot below of the mission today is courtesy of the Idaho Heritage Trust, which has been instrumental in many restoration projects at what is now called Coeur d’Alene’s Old Mission State Park.

Published on August 29, 2018 05:00