Rick Just's Blog, page 225

August 17, 2018

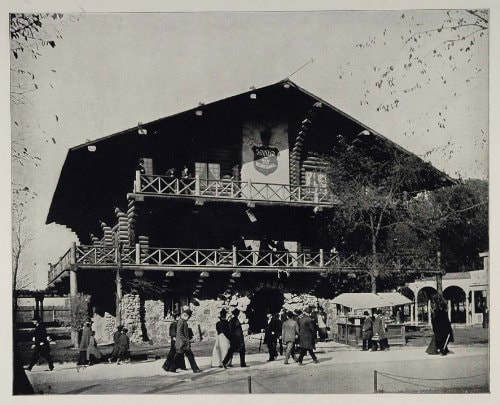

The Idaho Building

Every state wanted to be a part of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Idaho was no exception. Each building was designed to show off the major features and resources of the state. Idaho, barely out of diapers, played up on the frontier image by presenting a massive, rustic, three-story log building.

It was important that people would get the flavor of Idaho so, of course, the developers of the exhibit went to Spokane to find an architect. We shouldn’t be too hard on them for not choosing an Idaho architect, though. The pickings were slim in 1893, and K.K. Cutter, of Spokane, was the foremost architect in the Pacific Northwest.

Cutter had received his education in New York, but it was the architecture of Europe from which he drew much influence. The Idaho Building would not look out of place in Austria or Switzerland. Or Sun Valley, some years later.

The building itself was all Idaho, using 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. Stone work came from Nez Perce County, and the foundation veneer of lava rock was from southern Idaho.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City,” with most structures following that theme. The Idaho building stuck out like… a huge cabin surrounded by marble.

As anyone who ever played with Lincoln Logs as a kid knows, cabins—even gigantic cabins—can be taken apart and rebuilt again somewhere else. That’s what happened to the Idaho Building. At the end of the Exposition it was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

It was important that people would get the flavor of Idaho so, of course, the developers of the exhibit went to Spokane to find an architect. We shouldn’t be too hard on them for not choosing an Idaho architect, though. The pickings were slim in 1893, and K.K. Cutter, of Spokane, was the foremost architect in the Pacific Northwest.

Cutter had received his education in New York, but it was the architecture of Europe from which he drew much influence. The Idaho Building would not look out of place in Austria or Switzerland. Or Sun Valley, some years later.

The building itself was all Idaho, using 22 types of lumber, all from Shoshone County. Stone work came from Nez Perce County, and the foundation veneer of lava rock was from southern Idaho.

The interior was uniquely Idaho. A frying pan clock with golden hands was set to Idaho time. The men’s reception room had a hunting knife for a latch. Some chairs were made from antlers and mountain lion skins. Guests drank from silver cups made in Idaho, until most of them disappeared. There was needlework from the ladies of Albion, watercolors of Idaho wildflowers from Post Falls, fossil rocks from Boise, and a mastodon tusk from Blackfoot.

The Columbian Exposition was billed as the “White City,” with most structures following that theme. The Idaho building stuck out like… a huge cabin surrounded by marble.

As anyone who ever played with Lincoln Logs as a kid knows, cabins—even gigantic cabins—can be taken apart and rebuilt again somewhere else. That’s what happened to the Idaho Building. At the end of the Exposition it was sold at auction and moved to Wisconsin where it was to be used on Lake Geneva as a retreat for orphaned boys. The wealthy owner who had it rebuilt on the lakeshore lost interest in the project, so the orphans never saw the building. It was used for a time as a residence for laborers building a road, then for ice storage. Somehow it got the reputation as being haunted by “Idaho cowboys.” That did not raise its resale value. In 1911, the building was torn down. Some of the logs were used for a municipal pier. The rest of the building seemed to vanish along with those ghosts.

Published on August 17, 2018 05:00

August 16, 2018

Gretchen Fraser

Some of our more famous Idahoans weren’t born here. They chose Idaho, which simply indicates their good sense.

Gretchen Fraser was born in Tacoma, Washington. She fell in love with Idaho—and fell in love—in 1938 when she came to Sun Valley to compete in the Harriman Cup ski race. She met her future husband, Donald Fraser on the train traveling to Idaho. Donald had been a member of the 1936 US Olympic ski team. The two were married in 1939 and took up residence in Sun Valley. Both became members of the 1940 US Olympic ski team.

The 1940 games were canceled because of the war. It was 1948 before Gretchen got her chance to compete in the Olympics at age 29. She made the most of it, winning gold in the women’s slalom and silver in the combined event. She was the first American to win a gold medal in Olympic skiing.

Fraser continued to ski and promote the sport after her triumph. She made a couple of appearances in the movies as a stand-in skier for Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice” and that quintessential Sun Valley movie, “Sun Valley Serenade.” Fraser influenced future Olympians, mentoring Idaho medal winners Christin Cooper and Picabo Street, as well as Idahoan Muffy Davis, who won three gold medals in the Paralympics in 2012.

Gretchen Fraser was born in Tacoma, Washington. She fell in love with Idaho—and fell in love—in 1938 when she came to Sun Valley to compete in the Harriman Cup ski race. She met her future husband, Donald Fraser on the train traveling to Idaho. Donald had been a member of the 1936 US Olympic ski team. The two were married in 1939 and took up residence in Sun Valley. Both became members of the 1940 US Olympic ski team.

The 1940 games were canceled because of the war. It was 1948 before Gretchen got her chance to compete in the Olympics at age 29. She made the most of it, winning gold in the women’s slalom and silver in the combined event. She was the first American to win a gold medal in Olympic skiing.

Fraser continued to ski and promote the sport after her triumph. She made a couple of appearances in the movies as a stand-in skier for Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice” and that quintessential Sun Valley movie, “Sun Valley Serenade.” Fraser influenced future Olympians, mentoring Idaho medal winners Christin Cooper and Picabo Street, as well as Idahoan Muffy Davis, who won three gold medals in the Paralympics in 2012.

Published on August 16, 2018 05:00

August 15, 2018

Lapwai

There are a couple of stories about how Lapwai got its name. In the Lewis and Clark journals the name is mentioned as coming from the Nez Perce word “Lap-pit,” meaning “two country” or boundary. Kudos to Lewis and Clark for all they did, but they may not have been the best interpreters of the Nez Perce language.

The story more often told and, importantly, told by the city fathers of Lapwai is that it comes from the Nez Perce word “thlap-thlap,” which refers to the sound made by butterfly wings. That onomatopoeic word is a better fit, I think. It would mean the “land or place of the butterfly” or “valley of the butterfly.”

That little name holds a lot of history. It was Lapwai where Henry Harmon Spalding and his wife, Elizabeth, founded the first mission in what would become Idaho, in 1836. Elizabeth established the first school there, and became quite fluent in the native language. The Spaldings dug the first irrigation system and planted the first (wait for it) potatoes in what would become the Famous Potato state. North Idaho residents tire of being so heavily associated with potatoes, which are primarily grown in the southern part of the state, but, hey, they started it.

The first books printed in (eventual) Idaho came off the Lapwai Mission Press, the first press in the Pacific Northwest.

Fort Lapwai was operated by the military from 1862 to 1885. It was there that General Oliver Howard met with non-treaty Nez Perce on May 3, 1877 in a final attempt to head off the conflict that was then six weeks away. The Nez Perce National Historic Park is nearby at Spalding. It commemorates the history of the Nez Perce as well as their famous flight in 1877. It’s a must stop for history buffs.

The story more often told and, importantly, told by the city fathers of Lapwai is that it comes from the Nez Perce word “thlap-thlap,” which refers to the sound made by butterfly wings. That onomatopoeic word is a better fit, I think. It would mean the “land or place of the butterfly” or “valley of the butterfly.”

That little name holds a lot of history. It was Lapwai where Henry Harmon Spalding and his wife, Elizabeth, founded the first mission in what would become Idaho, in 1836. Elizabeth established the first school there, and became quite fluent in the native language. The Spaldings dug the first irrigation system and planted the first (wait for it) potatoes in what would become the Famous Potato state. North Idaho residents tire of being so heavily associated with potatoes, which are primarily grown in the southern part of the state, but, hey, they started it.

The first books printed in (eventual) Idaho came off the Lapwai Mission Press, the first press in the Pacific Northwest.

Fort Lapwai was operated by the military from 1862 to 1885. It was there that General Oliver Howard met with non-treaty Nez Perce on May 3, 1877 in a final attempt to head off the conflict that was then six weeks away. The Nez Perce National Historic Park is nearby at Spalding. It commemorates the history of the Nez Perce as well as their famous flight in 1877. It’s a must stop for history buffs.

Published on August 15, 2018 05:00

August 14, 2018

Boise's Basque Radio Programs

The Basque Museum in Boise tells the fascinating story of the culture and history of a people who have long been an important part of the fabric of our lives in Idaho. There you’ll learn about the role language has played in that history, both in the way it sometimes separated Basques from others in the West and the way it kept the traditions of the community alive.

In 1949 some Basques in Boise thought of a way to send out words and music that would be familiar to sheepherders and other Basques across the spread of the West. They started a weekly radio program on KDSH (later KBOI) broadcast entirely in the Basque language (Euskra). The program featured news of loved ones, such as birthdays, weddings, and births, as well as news of the world, weather, and the latest music from Spain.

The show also aired on KGEM at one time. The photo is of Espe Alegria, the “Voice of the Basques” on KGEM in about 1954. With volunteer announcers, the Basque language program aired for 30 years.

In 1949 some Basques in Boise thought of a way to send out words and music that would be familiar to sheepherders and other Basques across the spread of the West. They started a weekly radio program on KDSH (later KBOI) broadcast entirely in the Basque language (Euskra). The program featured news of loved ones, such as birthdays, weddings, and births, as well as news of the world, weather, and the latest music from Spain.

The show also aired on KGEM at one time. The photo is of Espe Alegria, the “Voice of the Basques” on KGEM in about 1954. With volunteer announcers, the Basque language program aired for 30 years.

Published on August 14, 2018 05:00

August 13, 2018

A Famous Director's Days in Boise

What do Eraserhead, Elephant Man and Monroe Elementary have in common?

They all have connections to director David Lynch. Lynch, born in Missoula, spent several years in Boise when his dad was working for the US Department of Agriculture as a researcher in the 1950s. He attended both Monroe Elementary and South Junior High. His father’s job also took the family to Sandpoint for a while.

Lynch’s more famous movies also include Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, and Dune , though the latter was a bit of flop. TV audiences know him best as the creator of Twin Peaks .

In Boise Lynch was a little notorious for his bombs. Not the box office kind. He’s quoted on the City of Absurdity website as saying, “We were all, um, heavily into making bombs at that particular place and time.” He built one rocket out of match heads and was tamping them down when it went off, sending the rocket through his ankle. They “sewed [his] foot back on and [he] was okay after that.”

Until the next bombing. “We blew up a swimming pool. I was arrested.” He went on to say, “We didn't blow it up, we set off a bomb in there - actually for safety reasons. The pool was built off the ground. These bombs we were making were pipe bombs, and they would hit the ground and not explode until they were about eye level. And they would explode with such a force that the pipe would just completely turn inside out, and shrapnel would blow. We threw it in the pool so that the shrapnel would hit the side of the pool. We threw it in around ten o'clock Saturday morning, and the smoke came up shaped like the pool. This thing rose up just instantly shaped like the pool. Just for a moment, till the wind blew it. It filled the pool with smoke and it just took that shape. And you could hear it for, I don't know how far, but it shook windows supposedly for five blocks. It was a big bomb."

I did a little search for that incident in the Idaho Statesman with no success. I did find Lynch attending a swimming birthday party for a classmate, on the ski lift at Bogus, playing a brass instrument in a summer music program at South Junior High, elected as seventh grade president at South, on a dance committee, in a play, and earning a merit badge. So, clearly on the road to fame.

They all have connections to director David Lynch. Lynch, born in Missoula, spent several years in Boise when his dad was working for the US Department of Agriculture as a researcher in the 1950s. He attended both Monroe Elementary and South Junior High. His father’s job also took the family to Sandpoint for a while.

Lynch’s more famous movies also include Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, and Dune , though the latter was a bit of flop. TV audiences know him best as the creator of Twin Peaks .

In Boise Lynch was a little notorious for his bombs. Not the box office kind. He’s quoted on the City of Absurdity website as saying, “We were all, um, heavily into making bombs at that particular place and time.” He built one rocket out of match heads and was tamping them down when it went off, sending the rocket through his ankle. They “sewed [his] foot back on and [he] was okay after that.”

Until the next bombing. “We blew up a swimming pool. I was arrested.” He went on to say, “We didn't blow it up, we set off a bomb in there - actually for safety reasons. The pool was built off the ground. These bombs we were making were pipe bombs, and they would hit the ground and not explode until they were about eye level. And they would explode with such a force that the pipe would just completely turn inside out, and shrapnel would blow. We threw it in the pool so that the shrapnel would hit the side of the pool. We threw it in around ten o'clock Saturday morning, and the smoke came up shaped like the pool. This thing rose up just instantly shaped like the pool. Just for a moment, till the wind blew it. It filled the pool with smoke and it just took that shape. And you could hear it for, I don't know how far, but it shook windows supposedly for five blocks. It was a big bomb."

I did a little search for that incident in the Idaho Statesman with no success. I did find Lynch attending a swimming birthday party for a classmate, on the ski lift at Bogus, playing a brass instrument in a summer music program at South Junior High, elected as seventh grade president at South, on a dance committee, in a play, and earning a merit badge. So, clearly on the road to fame.

Published on August 13, 2018 05:00

August 12, 2018

Art Deco Courthouses

Government buildings are often unimaginative cubes designed with little thought of beauty. Yet, much of Idaho’s most interesting architecture can be found in government buildings. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was responsible for funding seven county courthouses in Idaho, all with in the Art Deco style. Art Deco came into vogue in the US and Europe in the 1920s. The style found its way into architecture, as well as furniture, jewelry, cars, fashion and everyday objects such as radios. It was a modern style that often infused functional objects from buildings to vacuum cleaners with artistic touches.

The following were all built using WPA funding. All are Art Deco, and all are also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Boundary County Courthouse in Bonners Ferry was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941. National Register of Historic Places.

The brick Cassia County Courthouse in Burley was built in 1939.

The Franklin County Courthouse in Preston was built in 1939. Hyrum Pope, of Salt Lake City, was the architect. Pope died of a heart attack while on site inspecting construction of the building.

The Gem County Courthouse in Emmett was designed by Frank Hummel of the Boise firm Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1938.

The Jefferson County Courthouse in Rigby was built in 1938. Idaho Falls architects Sundberg and Sundberg designed it.

The Jerome County Courthouse, in Jerome was built in 1939.

The Oneida County Courthouse in Malad was built in 1938 from plans drawn up by Sundberg and Sundberg.

The Washington County Courthouse in Weiser, was designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1939.

The following were all built using WPA funding. All are Art Deco, and all are also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Boundary County Courthouse in Bonners Ferry was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941. National Register of Historic Places.

The brick Cassia County Courthouse in Burley was built in 1939.

The Franklin County Courthouse in Preston was built in 1939. Hyrum Pope, of Salt Lake City, was the architect. Pope died of a heart attack while on site inspecting construction of the building.

The Gem County Courthouse in Emmett was designed by Frank Hummel of the Boise firm Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1938.

The Jefferson County Courthouse in Rigby was built in 1938. Idaho Falls architects Sundberg and Sundberg designed it.

The Jerome County Courthouse, in Jerome was built in 1939.

The Oneida County Courthouse in Malad was built in 1938 from plans drawn up by Sundberg and Sundberg.

The Washington County Courthouse in Weiser, was designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1939.

Published on August 12, 2018 05:00

August 11, 2018

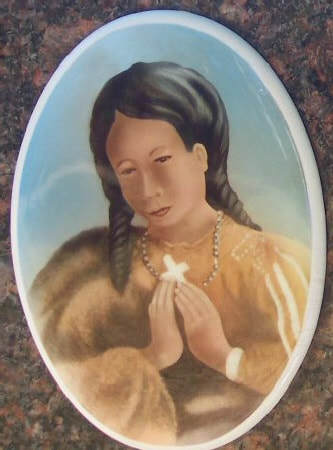

Siuwheem

The people who called themselves Schitsu'Umsh, now commonly known as the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, have a legend about the coming of white men. Tribal tradition says that Chief Circling Raven climbed a mountain on a vision quest and came back with a prophecy that two black-robed angels with white skin would come to teach his people of the great spirit.

So it is not surprising that his granddaughter, Siuwheem, meaning “tranquil waters,” would be among the first to be baptized by Father Pierre-Jean De Smet in 1842. The black-robed priest was setting up missions in the West, and he was then starting one near present-day St. Maries in northern Idaho.

The St. Joseph’s Mission was constructed on the banks of the St. Joe River. Frequent flooding at that site caused the missionaries to soon abandon it. They moved to a hill overlooking the Coeur d’Alene River near present day Cataldo in 1846. They built what would become the Mission of the Sacred Heart there between 1850 and 1853. It stands today as Idaho’s oldest building.

Siuwheem has her own tribal legends. Two stories laud her for stopping battles, first with Spokane Indians, and then with the Nez Perce. As a teenager she married a member of the Spokane Tribe called Polotkin. Upon their baptism Father De Smet gave her the name Louise, and her husband the name Adolph, not only baptizing both but uniting them in marriage. From that point on Siuwheem was known as Louise Siuwheem Polotkin.

Louise was a talented translator and a fervent believer in the new religion the missionaries brought with them. She had a special love for children, especially girls, and took in several who their parents couldn’t care for.

Her grave marker includes the words “She taught religion to the children, cared for the sick and the orphans, taught hymns and prayers and came to this cemetery every night to pray for those buried here.” That marker, which includes the painting of the woman below, stands in the small cemetery on the grounds of the Mission of the Sacred Heart, which was later renamed in honor of another priest. It became the Cataldo Mission of the Sacred Heart. You can visit the grave and the mission at Coeur d’Alenes Old Mission State Park just off Exit 39 of I90 east of Coeur d’Alene.

So it is not surprising that his granddaughter, Siuwheem, meaning “tranquil waters,” would be among the first to be baptized by Father Pierre-Jean De Smet in 1842. The black-robed priest was setting up missions in the West, and he was then starting one near present-day St. Maries in northern Idaho.

The St. Joseph’s Mission was constructed on the banks of the St. Joe River. Frequent flooding at that site caused the missionaries to soon abandon it. They moved to a hill overlooking the Coeur d’Alene River near present day Cataldo in 1846. They built what would become the Mission of the Sacred Heart there between 1850 and 1853. It stands today as Idaho’s oldest building.

Siuwheem has her own tribal legends. Two stories laud her for stopping battles, first with Spokane Indians, and then with the Nez Perce. As a teenager she married a member of the Spokane Tribe called Polotkin. Upon their baptism Father De Smet gave her the name Louise, and her husband the name Adolph, not only baptizing both but uniting them in marriage. From that point on Siuwheem was known as Louise Siuwheem Polotkin.

Louise was a talented translator and a fervent believer in the new religion the missionaries brought with them. She had a special love for children, especially girls, and took in several who their parents couldn’t care for.

Her grave marker includes the words “She taught religion to the children, cared for the sick and the orphans, taught hymns and prayers and came to this cemetery every night to pray for those buried here.” That marker, which includes the painting of the woman below, stands in the small cemetery on the grounds of the Mission of the Sacred Heart, which was later renamed in honor of another priest. It became the Cataldo Mission of the Sacred Heart. You can visit the grave and the mission at Coeur d’Alenes Old Mission State Park just off Exit 39 of I90 east of Coeur d’Alene.

Published on August 11, 2018 05:00

August 10, 2018

The Mysterious Almo Massacre

So, here’s the story, as commemorated on an Idaho-shaped marker in the tiny Idaho town of Almo. “Dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives in a horrible Indian Massacre, 1861. Three hundred immigrants west bound. Only five escaped. –Erected by S & D of Idaho Pioneers, 1938.”

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back , by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back , by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

Published on August 10, 2018 05:00

August 9, 2018

Steve Eaton

You’ve probably heard a song written by Boisean Steve Eaton and didn’t even know it. He’s written songs recorded by Ann Murray, Lee Greenwood, Glen Campbell, the Righteous Brothers, Art Garfunkel, the Fifth Dimension, and others. He once called his home (then) in Pocatello, “the house The Carpenters built.” Kind of a double entendre, that. He wasn’t referring to the folks who handled the hammers. It was his song “All You Get from Love is a Love Song” that was a big hit for brother and sister Richard and Karen Carpenter, the pop duo of the 70s and 80s that built the house.

Eaton formed a band called King Charles and The Counts in Pocatello. He and the band members dropped out of high school and moved to Hollywood. They got a record contract with a small label, Charger Crusader Records. Then in the early 70s he formed the band Fat Chance, which signed with RCA. They performed at The Troubadour in Los Angeles and opened for British pop band Yes on a national tour.

Fat Chance didn’t last long. When they broke up, Eaton got a contract with Capitol Records for a couple of albums. Recently one of his early records, “Hey Mr. Dreamer,” was featured on the YouTube program, How was that not a hit? Listen to it here.

Today royalties keep rolling in for his songwriting and he performs two or three nights a week around Boise. He continues to write, and has received a couple of Emmy nominations for music written for PBS specials.

Eaton formed a band called King Charles and The Counts in Pocatello. He and the band members dropped out of high school and moved to Hollywood. They got a record contract with a small label, Charger Crusader Records. Then in the early 70s he formed the band Fat Chance, which signed with RCA. They performed at The Troubadour in Los Angeles and opened for British pop band Yes on a national tour.

Fat Chance didn’t last long. When they broke up, Eaton got a contract with Capitol Records for a couple of albums. Recently one of his early records, “Hey Mr. Dreamer,” was featured on the YouTube program, How was that not a hit? Listen to it here.

Today royalties keep rolling in for his songwriting and he performs two or three nights a week around Boise. He continues to write, and has received a couple of Emmy nominations for music written for PBS specials.

Published on August 09, 2018 05:00

August 8, 2018

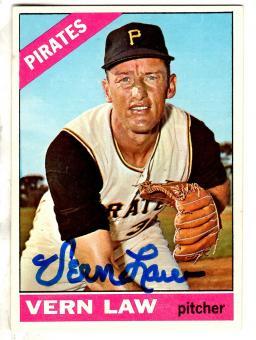

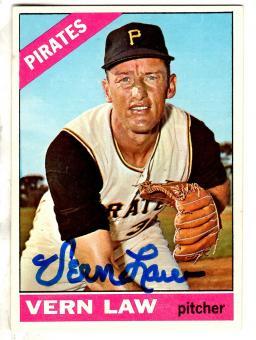

Idaho's Vern Law

When you think of baseball players from Idaho, you might think of Harmon Kilibrew or Walter Johnson. Great players. But, don’t forget about Vern Law.

Born in Meridian, in 1930, Law first pitched in the majors for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1950. He played just one season, then left to serve in the military from 1951-1954. He returned to the Pirates and had his best year in 1960, when he won the Cy Young award and helped his team win the World Series against the New York Yankees. He was the winning pitcher in two series games.

An injury in 1963 forced him on to the voluntary retired list. In 1965, he was back on the mound, and received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as comeback player of the year. He left the game in 1967.

Law had a career win-loss record of 162-147. He had a 3.77 earned run average, and played in the All-Star game twice.

Law, who is LDS, got some ribbing for his devout beliefs. He was nicknamed “The Deacon” He was known for some great quotes, including “A winner never quits and a quitter never wins.”

Born in Meridian, in 1930, Law first pitched in the majors for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1950. He played just one season, then left to serve in the military from 1951-1954. He returned to the Pirates and had his best year in 1960, when he won the Cy Young award and helped his team win the World Series against the New York Yankees. He was the winning pitcher in two series games.

An injury in 1963 forced him on to the voluntary retired list. In 1965, he was back on the mound, and received the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award as comeback player of the year. He left the game in 1967.

Law had a career win-loss record of 162-147. He had a 3.77 earned run average, and played in the All-Star game twice.

Law, who is LDS, got some ribbing for his devout beliefs. He was nicknamed “The Deacon” He was known for some great quotes, including “A winner never quits and a quitter never wins.”

Published on August 08, 2018 05:00