Rick Just's Blog, page 229

July 8, 2018

Basque Boarding Houses

Assimilating into a new country and culture is not something that is done overnight. The Basques had some unique ways of coping with the stress of immigration.

You may think of Basques as sheepherders because in this country they often were. For most of them it wasn’t a way of life they had known in the Old Country. It was simply a job that they could learn quickly and one that didn’t require them to take on a new language immediately. The sheep didn’t care what language they spoke.

With themselves for company Basque Sheepherders got along fine during the warm months of the year. But what to do come winter? Their solution was to come together in Basque boarding houses where they could speak the language they knew, eat familiar food, and socialize with their own people. At the same time, the boarding houses were in towns where English was common and they could learn more about their adopted country.

During much of the Twentieth Century you could find Basque boarding houses, or ostatuak, in Boise, Caldwell, Cascade, Emmett, Gooding, Hailey, Jerome, Mackay, Mountain Home, Mullan, Nampa, Pocatello, Rupert, Shoshone, and Twin Falls. There were more than 50 of them in Boise, alone, including one at the city’s oldest standing brick building, the Jacobs-Uberuaga House (photo), built in 1864. It became a Basque boarding house in 1910. The house is now the physical and historical center of Boise’s Basque Block.

You may think of Basques as sheepherders because in this country they often were. For most of them it wasn’t a way of life they had known in the Old Country. It was simply a job that they could learn quickly and one that didn’t require them to take on a new language immediately. The sheep didn’t care what language they spoke.

With themselves for company Basque Sheepherders got along fine during the warm months of the year. But what to do come winter? Their solution was to come together in Basque boarding houses where they could speak the language they knew, eat familiar food, and socialize with their own people. At the same time, the boarding houses were in towns where English was common and they could learn more about their adopted country.

During much of the Twentieth Century you could find Basque boarding houses, or ostatuak, in Boise, Caldwell, Cascade, Emmett, Gooding, Hailey, Jerome, Mackay, Mountain Home, Mullan, Nampa, Pocatello, Rupert, Shoshone, and Twin Falls. There were more than 50 of them in Boise, alone, including one at the city’s oldest standing brick building, the Jacobs-Uberuaga House (photo), built in 1864. It became a Basque boarding house in 1910. The house is now the physical and historical center of Boise’s Basque Block.

Published on July 08, 2018 05:00

July 7, 2018

The Roaring Soda Springs Geyser

Soda Springs is famous for its geyser as well as the several mineral springs in the area. Perhaps only Old Faithful Geyser in Yellowstone National Park comes close to matching the regularity of the Soda Springs Geyser. Old Faithful blows into the air every 44 to 125 minutes. The Soda Springs geyser erupts every hour on the hour, but it gets a little help from a mechanical valve with a timer.

In 1937 local businessmen had in mind using the geothermal water that bubbled up in Pyramid Spring as the featured draw for a commercial bathhouse. They figured they could drill down to the source and pipe the water to the attraction they planned to build.

On November 28, they might have yelled “Eureka!” That was the day they hit the pressurized hot water at 315 feet. Once they removed the bit the water shot 70 feet into the air. But the water began to cool after a few days, and they discovered it had a high mineral content that made it impractical for commercial development. They capped the hole.

The National Park Service took notice, and the secretary of the interior cautioned the people of Soda Springs that they should turn off their geyser for good because "...it is throwing the world famous 'Old Faithful Geyser' off schedule."

That there was some direct connection between the Soda Springs geyser and Old Faithful, 134 miles to the northeast, was pure fantasy. But the town leaders saw the value of having a captured geyser, so they installed a valve and timer on the old drill hole. You can see the geyser today blow 70 feet into the air, and hear it roar “like a mad dragon,” as one of the developers described the geyser in 1937.

In 1937 local businessmen had in mind using the geothermal water that bubbled up in Pyramid Spring as the featured draw for a commercial bathhouse. They figured they could drill down to the source and pipe the water to the attraction they planned to build.

On November 28, they might have yelled “Eureka!” That was the day they hit the pressurized hot water at 315 feet. Once they removed the bit the water shot 70 feet into the air. But the water began to cool after a few days, and they discovered it had a high mineral content that made it impractical for commercial development. They capped the hole.

The National Park Service took notice, and the secretary of the interior cautioned the people of Soda Springs that they should turn off their geyser for good because "...it is throwing the world famous 'Old Faithful Geyser' off schedule."

That there was some direct connection between the Soda Springs geyser and Old Faithful, 134 miles to the northeast, was pure fantasy. But the town leaders saw the value of having a captured geyser, so they installed a valve and timer on the old drill hole. You can see the geyser today blow 70 feet into the air, and hear it roar “like a mad dragon,” as one of the developers described the geyser in 1937.

Published on July 07, 2018 05:00

July 6, 2018

Locked up at the Statehouse

There are many beautiful doors in Idaho’s statehouse. Most are wooden, many with glass or frosted glass windows in the upper half. Two, though, are unique. To enter certain offices in the Idaho Capitol, you step through the openings of door-sized safes. The gleaming steel doors with hefty metal latches, knurled knobs, and gold-leaf lettering once protected the state’s treasury back when physical money from tax revenues was kept there before finding its way to the bank.

There is little need for enormous vaults to protect cash anymore, but when the renovated statehouse was reopened to the public in 2010 we found that those historical doors—minor treasures in themselves—had been retained.

There is little need for enormous vaults to protect cash anymore, but when the renovated statehouse was reopened to the public in 2010 we found that those historical doors—minor treasures in themselves—had been retained.

Published on July 06, 2018 05:00

July 5, 2018

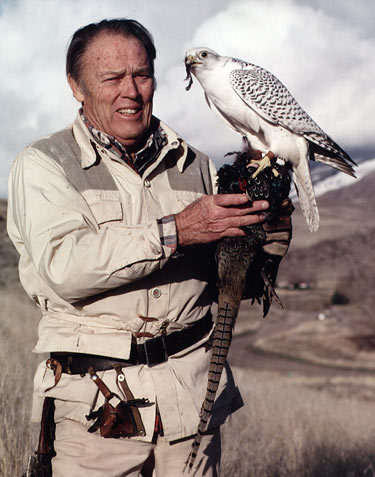

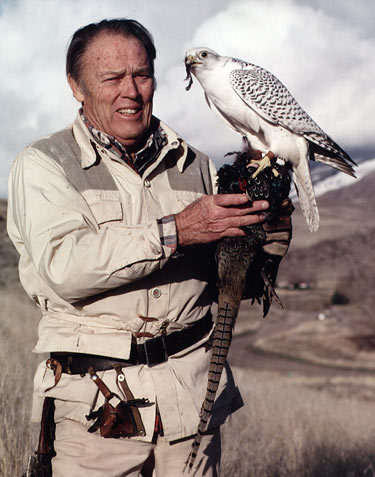

Morley Nelson

Idaho is a mecca for raptor lovers from all over the world. That’s because it is a magnet for birds of prey. The World Center for Birds of Prey is in Boise, Boise State University is home to the Raptor Research Center and offers the only Masters of Science in Raptor Research, and The Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area (NCA)is south of Kuna.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWII stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner. For a short video about the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, click here.

For a short video about the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, click here.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWII stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

For a short video about the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, click here.

For a short video about the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, click here.

Published on July 05, 2018 05:00

July 4, 2018

Idaho's Atomic Plane

What if you had an airplane that could circle the globe for years? That question intrigued military planners in the 1940s so much that the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS), near Idaho Falls, set to work building one. It would run on atomic power, you see.

The atomic airplane would weigh 300 tons, stretch 205 feet long and measure 136 feet from wingtip to wingtip. Big, but smaller than a 747.

The plane was a joint project of the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission that began in in 1946. The goal was to come up with a practical airplane that could fly 15,000 miles without having to land.

They built a big earth-shielded hangar for the plane. The photo shows construction and the completed hangar, which today is used for manufacturing tank armor.

That the plane’s hangar is being used for some other purpose is a clue about the plane itself. They did successfully test twin nuclear engines, but at 30 feet high they were a tad big for airplanes. Miniaturization might have been possible, eventually, if the project weren’t shelved in the early 60s. Technological problems, such shielding the pilots, weren’t what killed it. Fears that such a plane would eventually crash, making the accident site uninhabitable, brought it down before it ever went up, and before a prototype had been built.

Today, you can see the two Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment reactors, used in the effort to build an atomic-powered airplane. They sit in front of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I Atomic Museum at the site near Arco.

By the way the NRTS became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), then the Idaho National Lab (INL). It retains the latter designation today. Many people in eastern Idaho just call it The Site, rather than keep up with the acronyms.

Information about the nuclear plane comes largely from Susan Stacy’s book Proving the Principle, a History of the National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, 1949-1999 .

This illustration appeared in an October, 1951 edition of Popular Science.

This illustration appeared in an October, 1951 edition of Popular Science.

The atomic airplane would weigh 300 tons, stretch 205 feet long and measure 136 feet from wingtip to wingtip. Big, but smaller than a 747.

The plane was a joint project of the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission that began in in 1946. The goal was to come up with a practical airplane that could fly 15,000 miles without having to land.

They built a big earth-shielded hangar for the plane. The photo shows construction and the completed hangar, which today is used for manufacturing tank armor.

That the plane’s hangar is being used for some other purpose is a clue about the plane itself. They did successfully test twin nuclear engines, but at 30 feet high they were a tad big for airplanes. Miniaturization might have been possible, eventually, if the project weren’t shelved in the early 60s. Technological problems, such shielding the pilots, weren’t what killed it. Fears that such a plane would eventually crash, making the accident site uninhabitable, brought it down before it ever went up, and before a prototype had been built.

Today, you can see the two Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment reactors, used in the effort to build an atomic-powered airplane. They sit in front of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I Atomic Museum at the site near Arco.

By the way the NRTS became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), then the Idaho National Lab (INL). It retains the latter designation today. Many people in eastern Idaho just call it The Site, rather than keep up with the acronyms.

Information about the nuclear plane comes largely from Susan Stacy’s book Proving the Principle, a History of the National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, 1949-1999 .

This illustration appeared in an October, 1951 edition of Popular Science.

This illustration appeared in an October, 1951 edition of Popular Science.

Published on July 04, 2018 05:00

July 3, 2018

Rock Cairns in Idaho

You’ve probably seen a rock cairn somewhere in your travels. People with an artistic bent often leave little stacks of rock in or alongside riverbeds, a tribute to their balancing abilities.

Just don’t. Artistic as your stones may be, they are a distraction from the natural beauty people have come to see. Moving rocks around disturbs micro-ecosystems, often killing creepy crawly critters that might not be on anyone’s list of favorite animals, but are an important part of nature. If you must stack, do it in your yard. End of editorial.

Stone cairns are common on all continents. Stacking rocks is an ancient way to mark things. They may be memorial markers, markers to locate caches, and in later years, property markers on the corner of lots.

In Idaho, Basque sheepherders made stone cairns to mark trails or just to pass the time. They are called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. They could be over six feet tall. I remember one at the top of Garden Creek Peak in Bingham County when I was a kid. It may not have been a Basque cairn, since it was on the Forth Hall Reservation, but I remember my dad calling it a “sheepherders monument.” You could see it for miles around.

Post Office Creek, which runs into the Lochsa, got its name from a misunderstanding about Nez Perce cairns in the area. Meriwether Lewis wrote about them in his June 27, 1806 journal entry: “…on this eminence the nativs have raised a conic mound of Stons of 6 or 8 feet high and erected a pine pole of 15 feet long.” According to Borg Hendrickson and Linwood Laughy’s 1989 book, Clearwater Country!, two such mounds were at the head of the creek. They became known as Indian Post Office because people believed the Nez Perce left messages for one another on or in the cairns. Lewis had been told they were markers for trails and fishing sites, which seems more likely. Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.  Second photo, Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar

Second photo, Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar

Just don’t. Artistic as your stones may be, they are a distraction from the natural beauty people have come to see. Moving rocks around disturbs micro-ecosystems, often killing creepy crawly critters that might not be on anyone’s list of favorite animals, but are an important part of nature. If you must stack, do it in your yard. End of editorial.

Stone cairns are common on all continents. Stacking rocks is an ancient way to mark things. They may be memorial markers, markers to locate caches, and in later years, property markers on the corner of lots.

In Idaho, Basque sheepherders made stone cairns to mark trails or just to pass the time. They are called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. They could be over six feet tall. I remember one at the top of Garden Creek Peak in Bingham County when I was a kid. It may not have been a Basque cairn, since it was on the Forth Hall Reservation, but I remember my dad calling it a “sheepherders monument.” You could see it for miles around.

Post Office Creek, which runs into the Lochsa, got its name from a misunderstanding about Nez Perce cairns in the area. Meriwether Lewis wrote about them in his June 27, 1806 journal entry: “…on this eminence the nativs have raised a conic mound of Stons of 6 or 8 feet high and erected a pine pole of 15 feet long.” According to Borg Hendrickson and Linwood Laughy’s 1989 book, Clearwater Country!, two such mounds were at the head of the creek. They became known as Indian Post Office because people believed the Nez Perce left messages for one another on or in the cairns. Lewis had been told they were markers for trails and fishing sites, which seems more likely.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.  Second photo, Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar

Second photo, Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar

Published on July 03, 2018 05:00

July 2, 2018

Naming Pierce

Randy Stapilus’ book

Speaking Ill of the Dead, Jerks in Idaho History

is an interesting read. He has a chapter on Elias Davidson Pierce. Pierce’s jerkiness, in Randy’s telling, comes from his complete disregard for both advice from authorities and reservation boundaries. I recommend you read the book to find out more.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Idaho's first courthouse is in Pierce.

Idaho's first courthouse is in Pierce.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Idaho's first courthouse is in Pierce.

Idaho's first courthouse is in Pierce.

Published on July 02, 2018 05:00

July 1, 2018

That "Underground" School

When Amity School was built in southwest Boise, the design was ahead of its time. Only two other earth-sheltered schools were in existence in the US. And, if 50 years is the yardstick you use to measure what qualifies as a historical building—as many do—it is again ahead of its time. The Amity School is coming down this summer after 39 years of use.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School has reached the end of its days. It will be torn down this summer. A new school is already nearly finished right next door. When the earth-sheltered building goes, the earth will stay. The new playground will be built on the site of the old school.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979. Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School has reached the end of its days. It will be torn down this summer. A new school is already nearly finished right next door. When the earth-sheltered building goes, the earth will stay. The new playground will be built on the site of the old school.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym. You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors. The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances. The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

Published on July 01, 2018 05:00

June 30, 2018

Boise's Lincoln Statues

Boise has two statues of President Abraham Lincoln. The first is on the capitol grounds in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest Lincoln statue in the West. It was first installed at the Soldiers Home in 1915, then moved to the Idaho Veterans Home in East Boise. In 2009 it was moved to its present location. It's one of six duplicates of a piece sculpted by Alphonso Pelzer. The original statue is in New Jersey.

The other Lincoln is a giant sculpture, 9 feet tall, and he’s sitting on a bench. You can sit with him in Julia Davis Park. Why two Lincolns in Idaho? He signed the act creating Idaho Territory in 1863. Fun facts: the sitting Lincoln sculpture is a copy of one created by Gutzon Borglum. In spite of his weird name, you need to know that he carved the faces on Mount Rushmore and that he was born in St. Charles, Idaho Territory, in 1867. Oh, and the original of the sitting Lincoln is also in New Jersey.

The other Lincoln is a giant sculpture, 9 feet tall, and he’s sitting on a bench. You can sit with him in Julia Davis Park. Why two Lincolns in Idaho? He signed the act creating Idaho Territory in 1863. Fun facts: the sitting Lincoln sculpture is a copy of one created by Gutzon Borglum. In spite of his weird name, you need to know that he carved the faces on Mount Rushmore and that he was born in St. Charles, Idaho Territory, in 1867. Oh, and the original of the sitting Lincoln is also in New Jersey.

Published on June 30, 2018 05:00

June 29, 2018

Idaho's Presidential Trees

Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft shared Idaho roots. No, none of them were born here, and none of them lived here, but they all put down roots.

It started with President Harrison. When he visited Idaho in 1891 he planted a red oak in front of the southeast corner of the Territorial Capitol. A rock sugar maple was the next presidential planting. That came about in 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Boise and put his tree next to Harrison’s red oak. Finally, President Taft planted an Ohio Buckeye (yes, he was from Ohio) next to Roosevelt’s maple.

The trees thrived. The first two planted lasted over 100 years. They came down in 2006, not from some disease but by the chainsaw of progress. That was the year excavation began for the new underground wings at the statehouse. They couldn’t work around the trees.

One Legislator with a sense of history and a woodworking hobby took it upon himself to preserve some of the history of the Idaho presidential trees. Then Rep. Max Black (R), District 15, saved much of the wood from the trees.

According to a story Royce Williams wrote for Idaho Public Television, saving the presidential wood was a challenge. Although Black had arranged with a contractor to secure the wood, when the chainsaws came out, it was a different contractor doing the work. Some fast talking saved the wood. Black then had to scramble to find a place to store it temporarily, and find a longer-term storage site where it could cure. Black secured a portable sawmill and 20 volunteers to slice up the trees. He located kilns in Emmett, Boise, and Meridian where he could dry the lumber.

After curing the wood for 18 months, Black began delivering it to wood carvers around the state. Each carver got enough wood to make something for themselves, and a piece for public display. Those creations are on rotating display today in Statuary Hall in the renovated capitol building. One of several pieces carved from the presidential trees and on rotating display in the Idaho Statehouse. Photo by Royce Williams.

One of several pieces carved from the presidential trees and on rotating display in the Idaho Statehouse. Photo by Royce Williams.

It started with President Harrison. When he visited Idaho in 1891 he planted a red oak in front of the southeast corner of the Territorial Capitol. A rock sugar maple was the next presidential planting. That came about in 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Boise and put his tree next to Harrison’s red oak. Finally, President Taft planted an Ohio Buckeye (yes, he was from Ohio) next to Roosevelt’s maple.

The trees thrived. The first two planted lasted over 100 years. They came down in 2006, not from some disease but by the chainsaw of progress. That was the year excavation began for the new underground wings at the statehouse. They couldn’t work around the trees.

One Legislator with a sense of history and a woodworking hobby took it upon himself to preserve some of the history of the Idaho presidential trees. Then Rep. Max Black (R), District 15, saved much of the wood from the trees.

According to a story Royce Williams wrote for Idaho Public Television, saving the presidential wood was a challenge. Although Black had arranged with a contractor to secure the wood, when the chainsaws came out, it was a different contractor doing the work. Some fast talking saved the wood. Black then had to scramble to find a place to store it temporarily, and find a longer-term storage site where it could cure. Black secured a portable sawmill and 20 volunteers to slice up the trees. He located kilns in Emmett, Boise, and Meridian where he could dry the lumber.

After curing the wood for 18 months, Black began delivering it to wood carvers around the state. Each carver got enough wood to make something for themselves, and a piece for public display. Those creations are on rotating display today in Statuary Hall in the renovated capitol building.

One of several pieces carved from the presidential trees and on rotating display in the Idaho Statehouse. Photo by Royce Williams.

One of several pieces carved from the presidential trees and on rotating display in the Idaho Statehouse. Photo by Royce Williams.

Published on June 29, 2018 05:00