Rick Just's Blog, page 228

July 18, 2018

The Taylor Topper Guy

Once you’ve been a member of the U.S. Senate and a vice presidential candidate, what do you do with the rest of your life? The answer, for Glen Taylor, was to make hair pieces.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players (photo). When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players (photo). When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

Published on July 18, 2018 05:00

July 17, 2018

How Schweitzer Mountain got its Name

I find that readers are always eager to learn how some town or geographical feature came by its name. Today I’ll explain the genesis of the name Schweitzer Mountain, as best I can. There seems little information on Mr. Schweitzer except that he was something of a hermit who lived on the mountain and that he had served in the Swiss Army. Oh, and there’s the little detail about the cats.

Let’s start with a bit about Ella M. Farmin, courtesy of the book Idaho Women in History , by Betty Penson-Ward. Farmin was one of the earliest residents of Sandpoint, and is credited with civilizing the place a bit. At one time in the early days Sandpoint had 110 residents and 23 saloons, according to the book. Farmin turned one of those saloons into a Sunday School (at least on Sundays), and organized the Civic Club in town

Penson-Ward’s book is about Idaho women, so doesn’t mention Ella’s husband. The Farmins built the first house in Sandpoint, proving up their homestead in 1898.

I’m walking down this path with Ella Farmin, because in 1892 she was the telegraph operator who barely escaped an attack by “a crazy man.” The sheriff tracked the man to his cabin on the mountain where, as the story goes, he was “boiling cats for his dinner.” Pet cats had been going missing for some time and this seemed to explain that little mystery. Mr. Schweitzer was escorted to an asylum and disappeared from history, leaving only his last name behind to mark the mountain where he once lived.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

Let’s start with a bit about Ella M. Farmin, courtesy of the book Idaho Women in History , by Betty Penson-Ward. Farmin was one of the earliest residents of Sandpoint, and is credited with civilizing the place a bit. At one time in the early days Sandpoint had 110 residents and 23 saloons, according to the book. Farmin turned one of those saloons into a Sunday School (at least on Sundays), and organized the Civic Club in town

Penson-Ward’s book is about Idaho women, so doesn’t mention Ella’s husband. The Farmins built the first house in Sandpoint, proving up their homestead in 1898.

I’m walking down this path with Ella Farmin, because in 1892 she was the telegraph operator who barely escaped an attack by “a crazy man.” The sheriff tracked the man to his cabin on the mountain where, as the story goes, he was “boiling cats for his dinner.” Pet cats had been going missing for some time and this seemed to explain that little mystery. Mr. Schweitzer was escorted to an asylum and disappeared from history, leaving only his last name behind to mark the mountain where he once lived.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

This is the first ski lodge under construction at Schweitzer in 1963. The lodge later burned down and more elaborate facilities have replaced it. Lake Pend Oreille is in the distance.

Published on July 17, 2018 05:00

July 16, 2018

The Fosbury Flop

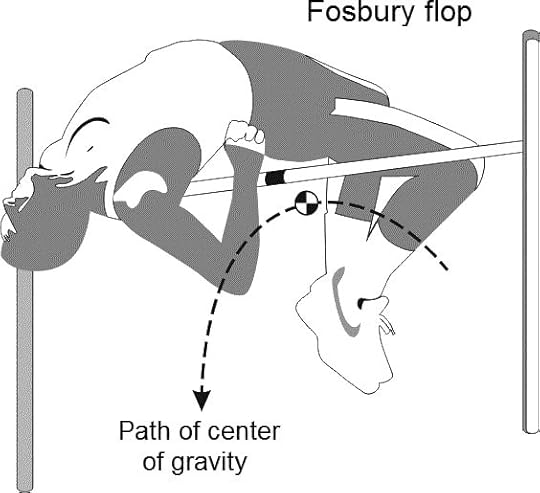

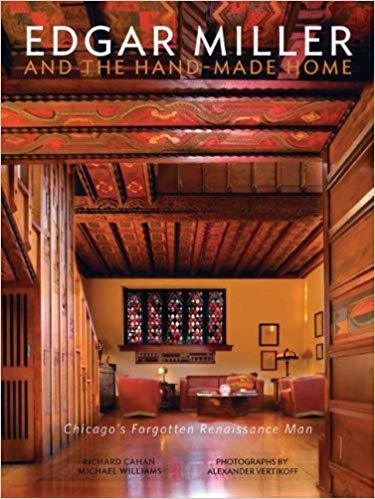

Idaho has a claim on a sport-changing Olympian. Or, maybe he has a claim on Idaho. When Dick Fosbury won the gold medal in the 1968 Olympics he hailed from Oregon. But in 1977, he moved to Ketchum where he still lives. He is one of the owners of Galena Engineering. He ran for a seat in the Idaho Legislature in 2014 against incumbent Steve Miller, but lost that race.

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Published on July 16, 2018 05:00

July 15, 2018

Hornikabrinika

Ah, what can one say about Hornikabrinka? Apparently, almost nothing. If you search for the word in the Idaho Statesman digital archives, you get several hits that talk about the 1913 revival of Hornikabrinka, which was to be held in conjunction with the semicentennial of the State of Idaho and the creation of Fort Boise that September. They were looking for “old-timers” who might be convinced to “reenact the stunts they used to do during the old time affairs.” What those stunts were is anyone’s guess.

There was little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

There was little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

In 1913 The Idaho Statesman ran a full page about the semicentennial celebration, including the above pictures of the parade. The Hornikabrinika was a part of the parade, but other entries were less tongue-in-cheek.

Published on July 15, 2018 05:00

July 14, 2018

FDR at Farragut

On October 3, 1942, the Kingston Daily Freeman printed the following, datelined Farragut Idaho. “No one knew the President of the United States was visiting the naval training station.

The two workmen looked up as a car went by.

Said one:

‘That almost looks like F.D.R. himself.’

Answered the other:

‘Yep, but he’s at the White House.’

They went back to work.”

It was FDR. He was on a secret nationwide tour of defense plants and military installations. The press was ordered not to cover his trip until two weeks after it was over. His stop in North Idaho took place on September 21, 1942.

The president’s relationship with the press during that time of war has received much analysis in later days. For one thing, the press seemed to shy away from any reference or photograph that might show FDR as anything less than at the top of his game. Pictures of him using a cane were rare. Even rarer were pictures of him in a wheelchair.

John Wood, well known for his history of railroads in the Coeur d’Alene mining area, shared with me a press photo of FDR on his visit to Farragut. He was going to PhotoShop out a few scratches, but when he looked closely at the picture he noticed someone had beaten him to it on the original. That is, the photo was altered in some interesting ways. First, someone seems to have dodged out a cigarette from FDR’s mouth. John also noticed that something was going on with the car’s visor on the right. It looks like there was a map clipped to it, most of which has been retouched to oblivion. When I looked at the photo I noticed one more little history-altering touch. Someone obliterated a hearing aid from FDR’s ear. In a way, it’s the most obvious alteration because it leaves a hearing-aid-shaped void.

For history buffs, this is interesting because it further illuminates to what extent the president’s public image was manipulated. To me the human frailties everyone was hiding only further emphasize the strengths FDR had.

Also pictured in the press photo is then Idaho Governor Chase Clark.

The full view of the FDR press photo.

The full view of the FDR press photo.  In this magnified version darkroom alterations can clearly be seen.

In this magnified version darkroom alterations can clearly be seen.

The two workmen looked up as a car went by.

Said one:

‘That almost looks like F.D.R. himself.’

Answered the other:

‘Yep, but he’s at the White House.’

They went back to work.”

It was FDR. He was on a secret nationwide tour of defense plants and military installations. The press was ordered not to cover his trip until two weeks after it was over. His stop in North Idaho took place on September 21, 1942.

The president’s relationship with the press during that time of war has received much analysis in later days. For one thing, the press seemed to shy away from any reference or photograph that might show FDR as anything less than at the top of his game. Pictures of him using a cane were rare. Even rarer were pictures of him in a wheelchair.

John Wood, well known for his history of railroads in the Coeur d’Alene mining area, shared with me a press photo of FDR on his visit to Farragut. He was going to PhotoShop out a few scratches, but when he looked closely at the picture he noticed someone had beaten him to it on the original. That is, the photo was altered in some interesting ways. First, someone seems to have dodged out a cigarette from FDR’s mouth. John also noticed that something was going on with the car’s visor on the right. It looks like there was a map clipped to it, most of which has been retouched to oblivion. When I looked at the photo I noticed one more little history-altering touch. Someone obliterated a hearing aid from FDR’s ear. In a way, it’s the most obvious alteration because it leaves a hearing-aid-shaped void.

For history buffs, this is interesting because it further illuminates to what extent the president’s public image was manipulated. To me the human frailties everyone was hiding only further emphasize the strengths FDR had.

Also pictured in the press photo is then Idaho Governor Chase Clark.

The full view of the FDR press photo.

The full view of the FDR press photo.  In this magnified version darkroom alterations can clearly be seen.

In this magnified version darkroom alterations can clearly be seen.

Published on July 14, 2018 05:00

July 13, 2018

An Influential Artist from Idaho Falls

Edgar Miller was born in or near Idaho Falls a few weeks before the turn to the Twentieth Century. He was destined to become a major force in the art and design worlds in that century.

Miller knocked around with his brother exploring what there was to explore near his home growing up. They would go camping for days in the nearby hills, where Edgar drew. And drew. Creating pictures of wildflowers was a passion. One of his high school teachers saw his talent and got him accepted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917.

He took to the city the way he took to his art, eventually creating a live-work art community much of which exists still today. Most famous for his stained glass, he was a pioneer in graphic art advertising, and influential in architecture.

Miller loved growing up in Idaho. He saw a painting of Custer’s Last Stand when he was four and from that moment wanted nothing more than to be an artist. He began sketching everything he saw. Much of his work was inspired by his childhood in and around the frontier town.

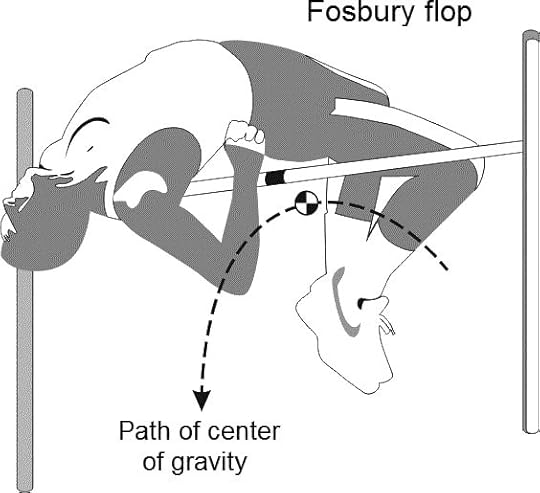

For more on Edgar Miller, see this Time Magazine slideshow of his work. A comprehensive article about Miller is available from on the CITYLAB website. The Edgar Miller Legacy is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art and "handmade homes" he created. Finally, there is quite a lavish book called Edgar Miller and the Hand-Made Home: Chicago's Forgotten Renaissance Man.

Thanks to architectural historian Julie Williams of Idaho Falls for telling me about Edgar Miller.

Miller knocked around with his brother exploring what there was to explore near his home growing up. They would go camping for days in the nearby hills, where Edgar drew. And drew. Creating pictures of wildflowers was a passion. One of his high school teachers saw his talent and got him accepted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917.

He took to the city the way he took to his art, eventually creating a live-work art community much of which exists still today. Most famous for his stained glass, he was a pioneer in graphic art advertising, and influential in architecture.

Miller loved growing up in Idaho. He saw a painting of Custer’s Last Stand when he was four and from that moment wanted nothing more than to be an artist. He began sketching everything he saw. Much of his work was inspired by his childhood in and around the frontier town.

For more on Edgar Miller, see this Time Magazine slideshow of his work. A comprehensive article about Miller is available from on the CITYLAB website. The Edgar Miller Legacy is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art and "handmade homes" he created. Finally, there is quite a lavish book called Edgar Miller and the Hand-Made Home: Chicago's Forgotten Renaissance Man.

Thanks to architectural historian Julie Williams of Idaho Falls for telling me about Edgar Miller.

Published on July 13, 2018 05:00

July 12, 2018

Dandy Lion Wine

Four years before the national prohibition of liquor, Idaho became a prohibition state on January 1, 1916. The Idaho Statesman seemed to treat it with good humor, lamenting that it "Would deprive many men of the only home they ever had." (See image)

But there also seemed an element in the paper, as there was in society in general, that had mixed opinions about it. On May 19, 1916, the Statesman reported on an alarming increase in dandelion wine in Boise: "Many owners of dandelion infested lawns have marveled lately at the number of children and grownups who asked permission to help extricate the little golden nuisances 'for a medicine that mother makes,' and have been enthusiastically granted permission.

"It has now earned the manufacture of dandelion wine has been carried on in many Boise homes in large quantities this spring."

State Chemist Jackson (no first name given) tested some of mamma's medicine and found it came in at 12.6 percent alcohol. He opined that perhaps it should be called "Dandy Lion" wine, because of its alcohol content.

The newspaper extolled the wine's virtues as a liver medicine, but cautioned that "many a strict prohibition mother is probably making the wine, never dreaming that she is a lawbreaker."

With those warnings out of the way, the paper proceeded to go give a complete recipe for making the wine.

But there also seemed an element in the paper, as there was in society in general, that had mixed opinions about it. On May 19, 1916, the Statesman reported on an alarming increase in dandelion wine in Boise: "Many owners of dandelion infested lawns have marveled lately at the number of children and grownups who asked permission to help extricate the little golden nuisances 'for a medicine that mother makes,' and have been enthusiastically granted permission.

"It has now earned the manufacture of dandelion wine has been carried on in many Boise homes in large quantities this spring."

State Chemist Jackson (no first name given) tested some of mamma's medicine and found it came in at 12.6 percent alcohol. He opined that perhaps it should be called "Dandy Lion" wine, because of its alcohol content.

The newspaper extolled the wine's virtues as a liver medicine, but cautioned that "many a strict prohibition mother is probably making the wine, never dreaming that she is a lawbreaker."

With those warnings out of the way, the paper proceeded to go give a complete recipe for making the wine.

Published on July 12, 2018 05:00

July 11, 2018

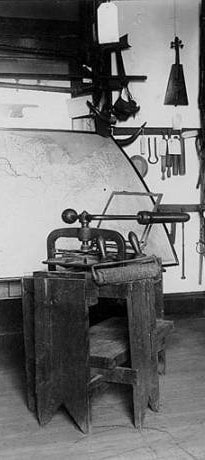

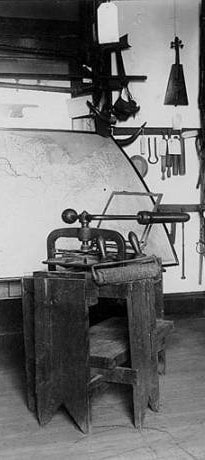

The Lapwai Press

Idaho became a state in 1890, as probably everyone reading this knows. It was 1959 before Hawaii became a state, yet it was to Hawaii that Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding turned to obtain a major machine of civilization. In 1838 Spalding wrote to the Congregational mission in Honolulu, “requesting the donation of a second-hand press and that the Sandwich Islands Mission should instruct someone, to be sent there from Oregon, in the art of printing, and in the meantime print a few small books in Nez Perces.”

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press , by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin tome it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statures, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press , by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin tome it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statures, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

Published on July 11, 2018 05:00

July 10, 2018

The Coeur d'Alene USO Fire

In 1935, Coeur d’Alene city leaders began talking about the need for a civic auditorium. Money is always tight for such aspirational projects, but the mission of the Works Project Administration (WPA), the largest agency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal program, was to create jobs. Building the city an auditorium would generate jobs during construction, and serve the community well into the future.

With the WPA putting up 65 percent of construction costs and providing the labor, work was begun on the auditorium in 1936. It hosted some events before its completion but wasn’t fully open until 1938.

It became the USO-Civic Auditorium in 1942 when military officials and USO personnel approached the city about providing off-base entertainment services for the “boots” at the new Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS), and smaller military facilities in the area. The United Service Organization (USO), a non-profit dedicated to providing entertainment to US troops, took over the operation of the building with the understanding that it would be returned to the City of Coeur d’Alene when it was no longer needed as a USO.

The beautiful log building (pictured) was in a city park adjacent to Lake Coeur d’Alene. Service members could enjoy the beach, weather permitting, and take part in dances, play ping pong, see movies, and just enjoy a little free time. More than 2,000 sailors a day visited the USO during its peak.

On October 9, 1945, a 17-year-old recruit from Farragut boarded a bus with fellow boots for a little R and R in town. William Barna, from New Jersey, had been at FNTS only three weeks. A 6th-grade drop-out, Barna had no explanation for his actions that night. What he did was methodically tear stuffing from the upholstery in three cars in preparation for lighting them on fire. Then, he went into the USO and surreptitiously unlocked a back door so he could get back in after the building was closed for the night. When the patrons and staff were gone, Barna entered through the door and began pulling down curtains. He piled them on the floor along with wads of paper, and set it all on fire.

The three cars and the log USO-Civic Auditorium went up in flames, a devastating loss to the community.

Barna was convicted of second-degree arson and given 5 to 10 years in the state prison. He served only four years before being released in 1949.

Much of the material for this post was taken from an article written by Don Pischner in the summer 2012 edition of the Museum of Northern Idaho’s newsletter.

With the WPA putting up 65 percent of construction costs and providing the labor, work was begun on the auditorium in 1936. It hosted some events before its completion but wasn’t fully open until 1938.

It became the USO-Civic Auditorium in 1942 when military officials and USO personnel approached the city about providing off-base entertainment services for the “boots” at the new Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS), and smaller military facilities in the area. The United Service Organization (USO), a non-profit dedicated to providing entertainment to US troops, took over the operation of the building with the understanding that it would be returned to the City of Coeur d’Alene when it was no longer needed as a USO.

The beautiful log building (pictured) was in a city park adjacent to Lake Coeur d’Alene. Service members could enjoy the beach, weather permitting, and take part in dances, play ping pong, see movies, and just enjoy a little free time. More than 2,000 sailors a day visited the USO during its peak.

On October 9, 1945, a 17-year-old recruit from Farragut boarded a bus with fellow boots for a little R and R in town. William Barna, from New Jersey, had been at FNTS only three weeks. A 6th-grade drop-out, Barna had no explanation for his actions that night. What he did was methodically tear stuffing from the upholstery in three cars in preparation for lighting them on fire. Then, he went into the USO and surreptitiously unlocked a back door so he could get back in after the building was closed for the night. When the patrons and staff were gone, Barna entered through the door and began pulling down curtains. He piled them on the floor along with wads of paper, and set it all on fire.

The three cars and the log USO-Civic Auditorium went up in flames, a devastating loss to the community.

Barna was convicted of second-degree arson and given 5 to 10 years in the state prison. He served only four years before being released in 1949.

Much of the material for this post was taken from an article written by Don Pischner in the summer 2012 edition of the Museum of Northern Idaho’s newsletter.

Published on July 10, 2018 05:00

July 9, 2018

The Sheriff Was a Weasel

In 1865, Ada County—which at the time included what are now Payette and Canyon counties—was in the market for its first sheriff. D.C. Updyke, who lately started a livery stable in Boise seemed like a good choice to the electorate. They might have had second thoughts if they’d been aware that Updyke was planning to use the playbook of Henry Plummer when he pinned on the badge.

In 1863, Plummer had been elected sheriff of Bannack, which was a part of Idaho Territory for a brief time. By the time local citizens figured out that Plummer was also the main instigator of local crime, Bannack was part of Montana Territory. Migrating borders were not nearly as concerning to the citizens of Bannack as providing for public safety. Plummer and two associates were hanged by local vigilantes in 1864.

But now it was 1865, and surely Ada County citizens would not make the same mistake as their counterparts in Montana. They elected D.C. Updyke and he took over as sheriff in March. There were a few items of official business that made the Idaho Statesman that year with Sherriff Updyke’s name attached. His name made the paper more often as one of the proprietors of D.C. Updyke and C.H. Warren’s stables.

A spot of trouble revealed itself that September when the sheriff was arrested for keeping money he collected that was meant for the county. Graft was not enough for Updyke, though. It turned out that he had probably been involved in other crimes, including stage robbery and murder. I say probably, because justice for Updyke came not in a court of law where such charges could be argued, but at the hands of vigilantes.

Sheriff D.C. Updyke and an accomplice were found hanged at Syrup Creek, not far from Rocky Bar, in April 1866. Pinned to Updyke’s body was a note that read:

DAVID UPDYKE,

The aider of Murderers and Horse Thieves.

XXX

The perpetrators elaborated by posting a card on Main Street in Idaho City a few days later. In the same handwriting as the above note, the card read:

DAVE UPDYKE

Accessory after the fact to the Port Neuf stage robbery.

Accessory and accomplice to the robbery of the stage near Boise City in 1864.

Chief conspirator in burning property on the Overland Stage line.

Guilty of aiding and assisting West Jenkens, the murderer, and other criminals to escape, while you were Sheriff of Ada County.

Accessory and accomplice to the murder of Raymond.

Threatening the lives and property of an already outraged and suffering community.

Justice has overtaken you.

XXX

Generally speaking, Ada County has had better luck with sheriffs ever since.

In 1863, Plummer had been elected sheriff of Bannack, which was a part of Idaho Territory for a brief time. By the time local citizens figured out that Plummer was also the main instigator of local crime, Bannack was part of Montana Territory. Migrating borders were not nearly as concerning to the citizens of Bannack as providing for public safety. Plummer and two associates were hanged by local vigilantes in 1864.

But now it was 1865, and surely Ada County citizens would not make the same mistake as their counterparts in Montana. They elected D.C. Updyke and he took over as sheriff in March. There were a few items of official business that made the Idaho Statesman that year with Sherriff Updyke’s name attached. His name made the paper more often as one of the proprietors of D.C. Updyke and C.H. Warren’s stables.

A spot of trouble revealed itself that September when the sheriff was arrested for keeping money he collected that was meant for the county. Graft was not enough for Updyke, though. It turned out that he had probably been involved in other crimes, including stage robbery and murder. I say probably, because justice for Updyke came not in a court of law where such charges could be argued, but at the hands of vigilantes.

Sheriff D.C. Updyke and an accomplice were found hanged at Syrup Creek, not far from Rocky Bar, in April 1866. Pinned to Updyke’s body was a note that read:

DAVID UPDYKE,

The aider of Murderers and Horse Thieves.

XXX

The perpetrators elaborated by posting a card on Main Street in Idaho City a few days later. In the same handwriting as the above note, the card read:

DAVE UPDYKE

Accessory after the fact to the Port Neuf stage robbery.

Accessory and accomplice to the robbery of the stage near Boise City in 1864.

Chief conspirator in burning property on the Overland Stage line.

Guilty of aiding and assisting West Jenkens, the murderer, and other criminals to escape, while you were Sheriff of Ada County.

Accessory and accomplice to the murder of Raymond.

Threatening the lives and property of an already outraged and suffering community.

Justice has overtaken you.

XXX

Generally speaking, Ada County has had better luck with sheriffs ever since.

Published on July 09, 2018 05:00