Rick Just's Blog, page 222

September 17, 2018

The Tyee

Logging was THE industry around Priest Lake in the latter part of the 19th century and much of the 20th. Diamond Match Company cut a lot of Western white pine around the lake so that people all around the world could strike a match.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake, if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake, if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

Published on September 17, 2018 05:00

September 16, 2018

Baseball at the Idanha

Dick d’Easum’s excellent book,

The Idanha

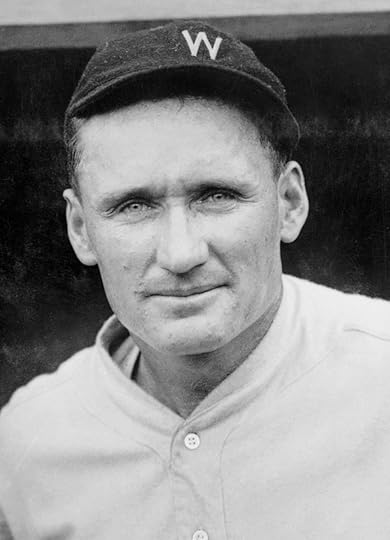

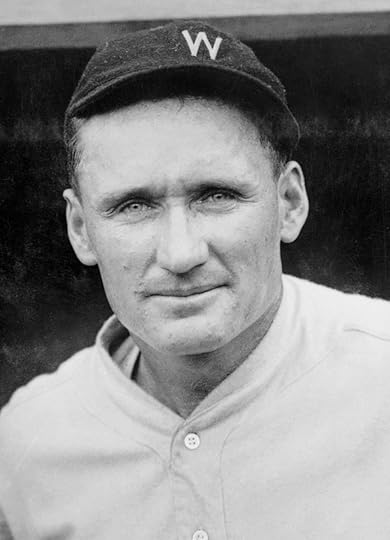

has dozens of stories about Boise’s famous hotel. I found the one about Baseball Hall of Famer Walter Johnson interesting, and a postscript to that one even more so.

The man who became known as “The Big Train” was well known in Idaho in the spring of 1907 because he was tearing up the fields as a semi-pro pitcher. His years with the Washington Senators were still ahead.

The Weiser Kids, for whom he pitched, were in town on the Fourth of July weekend to play a double-header against Boise. The day of the game it looked like rain. Everyone was expecting the game to be cancelled. Johnson didn’t want to let his arm lose its edge, so he grabbed catcher Guy Meats and began throwing pitches in the hallway of the Idanha. For verisimilitude they placed a chamber pot in front of Meats to fill in for home plate. The Train pitched one low, shattering the crockery, which one hopes was conveniently empty.

As it turned out, the game wasn’t cancelled. Johnson clobbered the Boise team. He would go on to pitch 74 innings without a score that summer, leading the Senators to call him up. He would pitch for them for the next 21 years, then manage the team for three years.

And now to that postscript to the story in d’Easum’s book. Baseball in those days was a nasty business with teams winning any way they could. In 1907 there was another pitcher in the league that was rated close to Johnson. He played for the Mountain Home team. Late in the season Boise and Mountain home were battling for second place—Weiser was going to win first, hands down.

Come the morning of the important game, the police showed up at the Idanha to arrest the pitcher from Mountain Home and one of his fielders on rape charges. Gosh, too bad they’d miss the game.

Boise lost anyway, so the set-up was to no avail. As it turned out the girls who were the alleged victims of the men were their girlfriends, one of whom was on the outs with one of the baseballers. When it came time for the trial the boys pled not guilty. They also pledged their love for the girls. The charges were dropped and the couples later participated in a double wedding. That’s baseball, I guess.

Walter Johnson in 1924.

Walter Johnson in 1924.

The man who became known as “The Big Train” was well known in Idaho in the spring of 1907 because he was tearing up the fields as a semi-pro pitcher. His years with the Washington Senators were still ahead.

The Weiser Kids, for whom he pitched, were in town on the Fourth of July weekend to play a double-header against Boise. The day of the game it looked like rain. Everyone was expecting the game to be cancelled. Johnson didn’t want to let his arm lose its edge, so he grabbed catcher Guy Meats and began throwing pitches in the hallway of the Idanha. For verisimilitude they placed a chamber pot in front of Meats to fill in for home plate. The Train pitched one low, shattering the crockery, which one hopes was conveniently empty.

As it turned out, the game wasn’t cancelled. Johnson clobbered the Boise team. He would go on to pitch 74 innings without a score that summer, leading the Senators to call him up. He would pitch for them for the next 21 years, then manage the team for three years.

And now to that postscript to the story in d’Easum’s book. Baseball in those days was a nasty business with teams winning any way they could. In 1907 there was another pitcher in the league that was rated close to Johnson. He played for the Mountain Home team. Late in the season Boise and Mountain home were battling for second place—Weiser was going to win first, hands down.

Come the morning of the important game, the police showed up at the Idanha to arrest the pitcher from Mountain Home and one of his fielders on rape charges. Gosh, too bad they’d miss the game.

Boise lost anyway, so the set-up was to no avail. As it turned out the girls who were the alleged victims of the men were their girlfriends, one of whom was on the outs with one of the baseballers. When it came time for the trial the boys pled not guilty. They also pledged their love for the girls. The charges were dropped and the couples later participated in a double wedding. That’s baseball, I guess.

Walter Johnson in 1924.

Walter Johnson in 1924.

Published on September 16, 2018 05:00

September 15, 2018

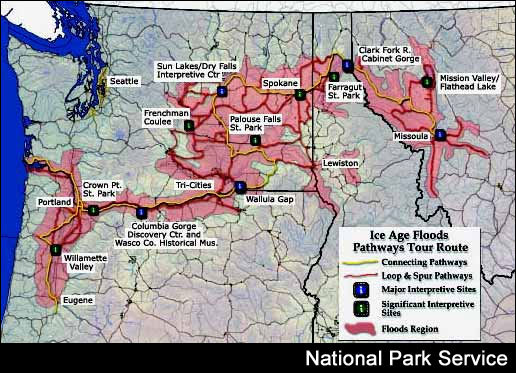

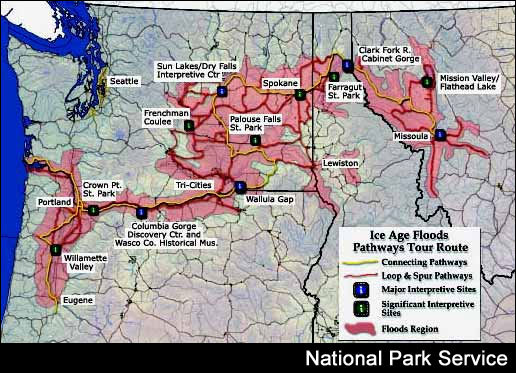

The Biggest Floods

There is some good-natured competition between north and south in our big state. Who has the best state parks? The best hunting and best fishing? The craziest politicians?

Bragging rights for one thing are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into the Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons, and ripped the top soil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

So, North Idaho, you win that one. Stay dry.

Bragging rights for one thing are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into the Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons, and ripped the top soil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

So, North Idaho, you win that one. Stay dry.

Published on September 15, 2018 05:00

September 14, 2018

Now and Then

Nowadays it seems every month or so cities are being challenged to deal with a new form of transportation that doesn’t quite fit with local ordinances and is driving someone bats. Uber and Lyft come to mind, as well as Boise Greenbike (which seems to be working pretty well). Electric bikes, razor scooters, skateboards, electric scooters, hover boards, Segways…

What was making teeth grind in 1912? Roller skates. “Boise Has Roller Skateritis” blasted the headline across the whole page on February 25 of that year.

Writer Thomas Ramage said that “All of the entire population of the city ranging from 7 to 16 years of age seems to have been smitten by the goddess of the roller skate and, at the present time there is a general epidemic of roller skateritis prevalent throughout the city and the suburbs.”

He went on to describe the rumbling of the skates and who you were likely to see wearing them from before dawn when the paper boy rattled by, to noontime deliveries clattering about “until the shadows of the night begins not only to fall but until they have landed. As late as 10 o’clock a stray child may be seen winding his way up Main street and up Seventh on his way home after having been rolled, jolted, bounced and banged all day long on his patent roller feet.”

Ramage concluded the lengthy article with, “Boise has roller skateritis and has it bad. Instead of walking from one place to another the boys ask each other to roll up to the store, the dairy or the meat market. There is only one place that they refuse to roll in, and that is the woodshed, when the pater familias is awaiting their arrival with a board with convenient holes bored in it.”

What was making teeth grind in 1912? Roller skates. “Boise Has Roller Skateritis” blasted the headline across the whole page on February 25 of that year.

Writer Thomas Ramage said that “All of the entire population of the city ranging from 7 to 16 years of age seems to have been smitten by the goddess of the roller skate and, at the present time there is a general epidemic of roller skateritis prevalent throughout the city and the suburbs.”

He went on to describe the rumbling of the skates and who you were likely to see wearing them from before dawn when the paper boy rattled by, to noontime deliveries clattering about “until the shadows of the night begins not only to fall but until they have landed. As late as 10 o’clock a stray child may be seen winding his way up Main street and up Seventh on his way home after having been rolled, jolted, bounced and banged all day long on his patent roller feet.”

Ramage concluded the lengthy article with, “Boise has roller skateritis and has it bad. Instead of walking from one place to another the boys ask each other to roll up to the store, the dairy or the meat market. There is only one place that they refuse to roll in, and that is the woodshed, when the pater familias is awaiting their arrival with a board with convenient holes bored in it.”

Published on September 14, 2018 05:00

September 13, 2018

Teenagers

Parents, of course you love your children. But be honest, haven’t you once or twice wished there was no such thing as a teenager? There was a time in Idaho history, and world history for that matter, when they did not exist.

The term teenager didn’t start making its way into popular usage until the 1930s and 1940s. The first instance of the word that I found in an Idaho paper was in the Statesman in 1941. It didn’t come up again there until 1943.

Teenage came along a little earlier, though newspapers were slow to standardize it. They used teen age, ‘teen age, “teen” age, and teen-age, depending on the whim of typesetters, perhaps. An expert on the teen-age from Chicago was speaking at a Boise church convention on “the boy problem” in 1914. Thank goodness we’ve now solved that one.

This wasn’t just about semantics. In a sense, there were no teenagers through most of recorded history. There were children who toddled around until they were five or six or seven, not contributing much to a family. Once they could start working at some menial labor, that’s what they did, simply becoming more useful as they got older.

The introduction of standardized education and child labor laws began to change this in the 19th century. Some scholars attribute the invention of the teenager, more-or-less as we know them today, to the automobile. Cars provided freedom for young people to occasionally get away from their parents. Dating became much more common. Then consolidated high schools began to use buses to bring students from further and further away. There they were, together, learning, dating, beginning to dress in their own fashions in the 1950s (picture). Voila! Teenagers!

I have done no research on the subject, but feel confident that eye rolling and insolence came into vogue about the same time as teenager.

The term teenager didn’t start making its way into popular usage until the 1930s and 1940s. The first instance of the word that I found in an Idaho paper was in the Statesman in 1941. It didn’t come up again there until 1943.

Teenage came along a little earlier, though newspapers were slow to standardize it. They used teen age, ‘teen age, “teen” age, and teen-age, depending on the whim of typesetters, perhaps. An expert on the teen-age from Chicago was speaking at a Boise church convention on “the boy problem” in 1914. Thank goodness we’ve now solved that one.

This wasn’t just about semantics. In a sense, there were no teenagers through most of recorded history. There were children who toddled around until they were five or six or seven, not contributing much to a family. Once they could start working at some menial labor, that’s what they did, simply becoming more useful as they got older.

The introduction of standardized education and child labor laws began to change this in the 19th century. Some scholars attribute the invention of the teenager, more-or-less as we know them today, to the automobile. Cars provided freedom for young people to occasionally get away from their parents. Dating became much more common. Then consolidated high schools began to use buses to bring students from further and further away. There they were, together, learning, dating, beginning to dress in their own fashions in the 1950s (picture). Voila! Teenagers!

I have done no research on the subject, but feel confident that eye rolling and insolence came into vogue about the same time as teenager.

Published on September 13, 2018 05:00

September 12, 2018

The Name Bannock

I’m doing a little research on Dr. Minnie Howard who was an interesting character for reasons I won’t get into now, because then that would be this post.

Dr. Howard lived in Pocatello and had a deep interest in history. She had a theory about where the tribal name Bannock came from. She thought the name came from the word “Bampneck,” which was a hairstyle where the hair is brushed back in a pompadour and tied in a knot at the nape of the neck.

A letter appeared in the March 13, 1938 edition of the Idaho Statesman from one J.C. York taking issue with that interpretation. Mr. York had been a clerk in the early days on the Fort Hall Reservation. He assisted in allotting lands there and settling the tribal members. A part of his duties was to record the genealogy and history of the Indians.

York, in learning their language and working with a trusted interpreter came to understand that the word “Pah” meant water in the Bannock language. When the interpreter would ask what they called themselves, elders would say “Pah ahnuck.” He did not know what “ahnuck” meant, so he asked. It was interpreted as meaning something like “across,” with the literal meaning of “People on, or over, or from, or across the water.”

The word was corrupted a bit into Bannock. York thought the confusion of Dr. Howard might have come from misunderstanding “nuck” and assuming that it meant neck.

I contacted some tribal members. They were inclined to believe Mr. York because of his careful study of first-hand sources.

I should mention that there is another definition of “bannock” that seems not to have originated with these tribal people. In Scottish and early English a bannock is a round, quick bread made from barely or oats, often fried on a griddle.

The Bannocks of more than a century ago were bison hunters and seasonal salmon fishers. They were indigenous in parts of what now are the states of Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Wyoming. As with many tribes, the coming of white men was not good news.

Today, the tribe is but a ghost of its former self. The 2010 U.S. counted 89 souls claiming Bannock or mixed Bannock lineage. Many of them live on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. The Indians there are often referred to as Shoshone-Bannock or even shortened to ShoBan. The two tribes are related.

Even with such a low population you may have heard of a couple of tribal members, both of whom I’ve mentioned in previous posts.

Mark Trahant is the editor of Indian Country Today and previously worked as a columnist for the Seattle Times and was the editorial page editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Trahant was the publisher of The Moscow-Pullman Daily News. He has also worked for the Salt Lake Tribune and the Arizona Republic and has reported for the PBS series Frontline.

Randy'L Teton, who served as the model for Sacagawea on the dollar coin traces part of her ancestry along the Bannock line. She is the public affairs manager for the Shoshone-Bannock tribes.

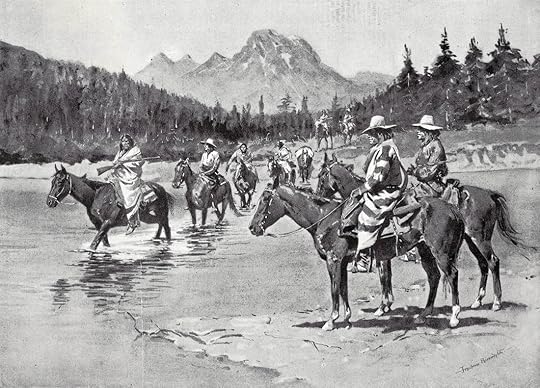

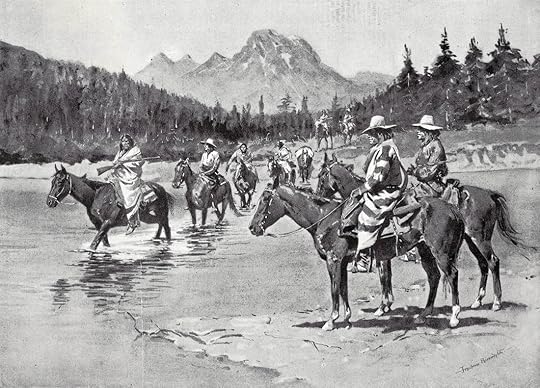

Illustration by Frederic Remington of a Bannock hunting party fording the Snake River during the Bannock War of 1895

Illustration by Frederic Remington of a Bannock hunting party fording the Snake River during the Bannock War of 1895

Dr. Howard lived in Pocatello and had a deep interest in history. She had a theory about where the tribal name Bannock came from. She thought the name came from the word “Bampneck,” which was a hairstyle where the hair is brushed back in a pompadour and tied in a knot at the nape of the neck.

A letter appeared in the March 13, 1938 edition of the Idaho Statesman from one J.C. York taking issue with that interpretation. Mr. York had been a clerk in the early days on the Fort Hall Reservation. He assisted in allotting lands there and settling the tribal members. A part of his duties was to record the genealogy and history of the Indians.

York, in learning their language and working with a trusted interpreter came to understand that the word “Pah” meant water in the Bannock language. When the interpreter would ask what they called themselves, elders would say “Pah ahnuck.” He did not know what “ahnuck” meant, so he asked. It was interpreted as meaning something like “across,” with the literal meaning of “People on, or over, or from, or across the water.”

The word was corrupted a bit into Bannock. York thought the confusion of Dr. Howard might have come from misunderstanding “nuck” and assuming that it meant neck.

I contacted some tribal members. They were inclined to believe Mr. York because of his careful study of first-hand sources.

I should mention that there is another definition of “bannock” that seems not to have originated with these tribal people. In Scottish and early English a bannock is a round, quick bread made from barely or oats, often fried on a griddle.

The Bannocks of more than a century ago were bison hunters and seasonal salmon fishers. They were indigenous in parts of what now are the states of Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Wyoming. As with many tribes, the coming of white men was not good news.

Today, the tribe is but a ghost of its former self. The 2010 U.S. counted 89 souls claiming Bannock or mixed Bannock lineage. Many of them live on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. The Indians there are often referred to as Shoshone-Bannock or even shortened to ShoBan. The two tribes are related.

Even with such a low population you may have heard of a couple of tribal members, both of whom I’ve mentioned in previous posts.

Mark Trahant is the editor of Indian Country Today and previously worked as a columnist for the Seattle Times and was the editorial page editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Trahant was the publisher of The Moscow-Pullman Daily News. He has also worked for the Salt Lake Tribune and the Arizona Republic and has reported for the PBS series Frontline.

Randy'L Teton, who served as the model for Sacagawea on the dollar coin traces part of her ancestry along the Bannock line. She is the public affairs manager for the Shoshone-Bannock tribes.

Illustration by Frederic Remington of a Bannock hunting party fording the Snake River during the Bannock War of 1895

Illustration by Frederic Remington of a Bannock hunting party fording the Snake River during the Bannock War of 1895

Published on September 12, 2018 05:00

September 11, 2018

Archie Teater

Frank Lloyd Wright designed only one home and studio for another artist. Can you guess where it is? Yes, it’s a fair bet the home is in Idaho, given the state-shaped geographical boundaries of this history series. But where in Idaho? Pssst! Say Hagerman.

Wright designed a home for Archie and Patricia Teater to be built near Hagerman in 1952. The house is perched above the Snake River just north of town. The site is called Teater’s Knoll. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house is privately owned, but occasionally opened for special events. A couple of books are available about the house, Teater’s Knoll: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Idaho Legacy and At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio.

But who was Teater? Born in 1901 in Boise, Archie Boyd Teater was a plein air landscape artist who painted mostly Western scenes. His oils were displayed alongside Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hart Benton. In his youth he worked alongside miners, trappers, and lumberjacks who probably cared little for Teater’s passion for painting, which would draw him away for days into the mountains where he would lose himself in the grandeur he meant to capture.

The Teater paintings below are owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and are on display at agency headquarters in Boise. The top painting is a view of Ritter Island, now a state park unit, from the cliffs above the island. On the bottom is a depiction of what the Thousand Springs once looked like from the island itself. A power generating structure now captures most of the flow of the springs and their once splendid beauty.

For more on the home check this Speaking of Idaho post.

Wright designed a home for Archie and Patricia Teater to be built near Hagerman in 1952. The house is perched above the Snake River just north of town. The site is called Teater’s Knoll. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house is privately owned, but occasionally opened for special events. A couple of books are available about the house, Teater’s Knoll: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Idaho Legacy and At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio.

But who was Teater? Born in 1901 in Boise, Archie Boyd Teater was a plein air landscape artist who painted mostly Western scenes. His oils were displayed alongside Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hart Benton. In his youth he worked alongside miners, trappers, and lumberjacks who probably cared little for Teater’s passion for painting, which would draw him away for days into the mountains where he would lose himself in the grandeur he meant to capture.

The Teater paintings below are owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and are on display at agency headquarters in Boise. The top painting is a view of Ritter Island, now a state park unit, from the cliffs above the island. On the bottom is a depiction of what the Thousand Springs once looked like from the island itself. A power generating structure now captures most of the flow of the springs and their once splendid beauty.

For more on the home check this Speaking of Idaho post.

Published on September 11, 2018 05:00

September 10, 2018

Banned in Boise

Ragtime music was all the rage in the US and Europe from about 1895 to 1918. The syncopated music of Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer” is a good example. Joplin’s music enjoyed a resurgence with the release of the 1973 motion picture The Sting . As with anything that looks like people are having too much fun, some railed against its vices.

Miss Lucy K. Cole, supervisor of music in Seattle’s public schools spoke of the evils of ragtime at a music teachers convention in 1913. Deriding dance halls she said, “There we find ragtime, coon songs, and the so-called ‘suggestive music.’ The saloonkeeper and the dance hall proprietor are neither musicians nor psychologists but they know from experience the kind of music that promotes their business.”

Admonitions were strong from the pulpit as well, and there were hints that it could cause one physical damage if not mental derangement.

So, of course, it was time for Boise’s city council to step in and solve the problem.

In October of 1912 that deliberative body passed an ordinance against dancing to ragtime music. Their scheme to enforce this was to license dance halls for a fee of $36 a year, and fine halls and dancers $100 if they were caught doing the “Grizzly Bear,” the “Bunny Hug,” or the “Turkey Trot.”

The Idaho Statesman in its Oct 12, 1912 edition announced the ban with all the pomp it deserved: “Good-bye to the dear old rag! The city council has spoken, and from its decision there is no appeal. No longer will the brawny beaux cut capers to music that is draggy…” “The city fathers have placed their official heel upon the neck of the ragtime dance, and in language that is forceful and descriptive have put the ban upon the soothing melodies that once put the brain in a whirl and music in the feet. No longer will the city tolerate the slow dragging across the ballroom floor, at the same time keeping up rhythmic gyrations of the shoulders. No, siree; it will not. The city fathers say that dancing is intended to be done by the feet and the feet alone.”

Whether anyone was arrested for doing the “Katzenjammer Glide” is unclear. Ragtime continued its popularity in Boise and elsewhere until jazz came along to push it out of the spotlight.

I was able to chase down this backwater bit of Boise history because I saw a mention of it in Betty Penson-Ward’s Idaho Women in History .

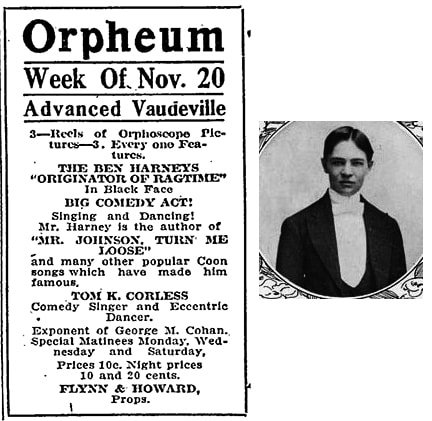

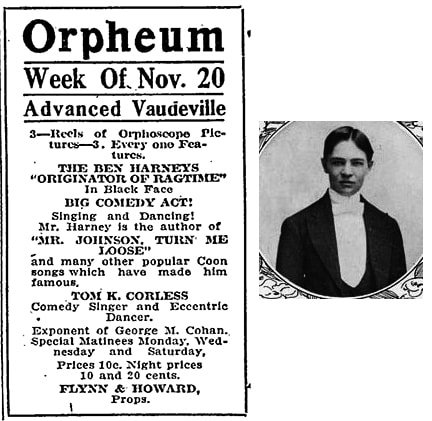

Ad for a performance by Ben Harney along with a picture of the man who popularized ragtime.

Ad for a performance by Ben Harney along with a picture of the man who popularized ragtime.

Ragtime music was all the rage in the US and Europe from about 1895 to 1918. The syncopated music of Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer” is a good example. Joplin’s music enjoyed a resurgence with the release of the 1973 motion picture The Sting . As with anything that looks like people are having too much fun, some railed against its vices.

Miss Lucy K. Cole, supervisor of music in Seattle’s public schools spoke of the evils of ragtime at a music teachers convention in 1913. Deriding dance halls she said, “There we find ragtime, coon songs, and the so-called ‘suggestive music.’ The saloonkeeper and the dance hall proprietor are neither musicians nor psychologists but they know from experience the kind of music that promotes their business.”

Admonitions were strong from the pulpit as well, and there were hints that it could cause one physical damage if not mental derangement.

So, of course, it was time for Boise’s city council to step in and solve the problem.

In October of 1912 that deliberative body passed an ordinance against dancing to ragtime music. Their scheme to enforce this was to license dance halls for a fee of $36 a year, and fine halls and dancers $100 if they were caught doing the “Grizzly Bear,” the “Bunny Hug,” or the “Turkey Trot.”

The Idaho Statesman in its Oct 12, 1912 edition announced the ban with all the pomp it deserved: “Good-bye to the dear old rag! The city council has spoken, and from its decision there is no appeal. No longer will the brawny beaux cut capers to music that is draggy…” “The city fathers have placed their official heel upon the neck of the ragtime dance, and in language that is forceful and descriptive have put the ban upon the soothing melodies that once put the brain in a whirl and music in the feet. No longer will the city tolerate the slow dragging across the ballroom floor, at the same time keeping up rhythmic gyrations of the shoulders. No, siree; it will not. The city fathers say that dancing is intended to be done by the feet and the feet alone.”

Whether anyone was arrested for doing the “Katzenjammer Glide” is unclear. Ragtime continued its popularity in Boise and elsewhere until jazz came along to push it out of the spotlight.

I was able to chase down this backwater bit of Boise history because I saw a mention of it in Betty Penson-Ward’s Idaho Women in History .

Ad for a performance by Ben Harney along with a picture of the man who popularized ragtime.

Ad for a performance by Ben Harney along with a picture of the man who popularized ragtime.

Published on September 10, 2018 09:00

September 9, 2018

The Sunbeam Dam

Today, when gathering energy from the sun through solar collectors is common, the word sunbeam as it pertains to energy is positive. The same was true in 1910 when the Sunbeam Dam was constructed on the Salmon River. It would positively power the Sunbeam mining operation up Jordan Creek from the new dam.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity, again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity, again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

Published on September 09, 2018 05:00

September 8, 2018

The Oregon Boot

The Oregon boot sounds like something you’d wear to watch a rodeo. If you were wearing one anytime from the 1890s to the 1950s in Idaho you were more likely to be looking for a hacksaw than pausing to gaze at cowboys.

The Oregon boot was invented in 1866 by Oregon State Penitentiary Warden J.C. Gardner. He called it the “Gardner Shackle” but that name never stuck. The devices didn’t come in pairs. Made to control prisoners, yet let them be somewhat mobile, Oregon boots were a heavy iron or lead weight—20-28 pounds—welded or bolted to metal braces that attached to a heavy shoe on one foot. It was like a ball and chain with no ball and no chain. Some had combination locks and some came apart with a key.

They worked very well from the point of view of law enforcement officials. From a prisoner’s point of view they were instruments of slow torture, causing leg, knee and hip problems that didn’t always go away once the boot was removed.

In 1911 “Reese the handcuff king” visited Boise as a special added attraction at the Orpheum theatre where, according to the Idaho Statesman, he removed an Oregon boot and handcuffs “in shorter order than it took to place them upon him, and without the aid of key.”

But it wasn’t so easy for the incarcerated. Many prisoners who wore them managed to escape. Sort of. They might get out of their cell, but making a speedy getaway was usually not in the cards. One prisoner pounded one against railroad tracks for hours, finally breaking the pin out of his boot. The rails were scarred by his efforts, which ultimately ended with his capture. One escapee dragged one 20 miles before being caught.

Diamond Field Jack Davis wore an Oregon boot while being transported from Albion to the Idaho State Penitentiary in Boise to await trial.

By the 1950s they were being used less and less. For a short time they became a metaphor. A March 19, 1950 story in the Idaho Statesman included this quote, “his leftist viewpoint proved to be an Oregon boot on the Democratic party.”

You can see an Oregon boot on display at the Old Idaho Penitentiary if you’d like to imagine what wearing one would have been like.

I found this creepy “Career Day” photo in the February 6, 1980 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

I found this creepy “Career Day” photo in the February 6, 1980 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

The Oregon boot was invented in 1866 by Oregon State Penitentiary Warden J.C. Gardner. He called it the “Gardner Shackle” but that name never stuck. The devices didn’t come in pairs. Made to control prisoners, yet let them be somewhat mobile, Oregon boots were a heavy iron or lead weight—20-28 pounds—welded or bolted to metal braces that attached to a heavy shoe on one foot. It was like a ball and chain with no ball and no chain. Some had combination locks and some came apart with a key.

They worked very well from the point of view of law enforcement officials. From a prisoner’s point of view they were instruments of slow torture, causing leg, knee and hip problems that didn’t always go away once the boot was removed.

In 1911 “Reese the handcuff king” visited Boise as a special added attraction at the Orpheum theatre where, according to the Idaho Statesman, he removed an Oregon boot and handcuffs “in shorter order than it took to place them upon him, and without the aid of key.”

But it wasn’t so easy for the incarcerated. Many prisoners who wore them managed to escape. Sort of. They might get out of their cell, but making a speedy getaway was usually not in the cards. One prisoner pounded one against railroad tracks for hours, finally breaking the pin out of his boot. The rails were scarred by his efforts, which ultimately ended with his capture. One escapee dragged one 20 miles before being caught.

Diamond Field Jack Davis wore an Oregon boot while being transported from Albion to the Idaho State Penitentiary in Boise to await trial.

By the 1950s they were being used less and less. For a short time they became a metaphor. A March 19, 1950 story in the Idaho Statesman included this quote, “his leftist viewpoint proved to be an Oregon boot on the Democratic party.”

You can see an Oregon boot on display at the Old Idaho Penitentiary if you’d like to imagine what wearing one would have been like.

I found this creepy “Career Day” photo in the February 6, 1980 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

I found this creepy “Career Day” photo in the February 6, 1980 edition of the Idaho Statesman.

Published on September 08, 2018 05:00