Rick Just's Blog, page 220

October 8, 2018

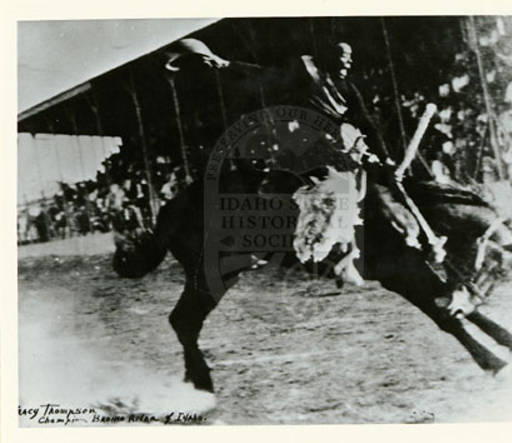

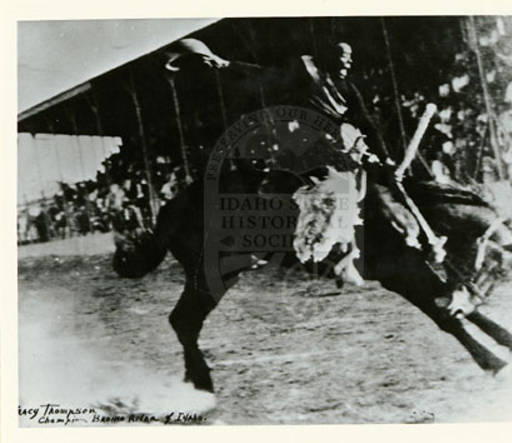

Tracy Thompson

On a recent visit to Boise’s Black History Museum I noticed a couple of lines on an interpretive panel about Tracy Thompson. I made a note to myself to do a little research to see if I could find out more. The answer to that question was, not really.

Tracy Thompson was a homesteader in Arimo before moving to Pocatello in 1919. He worked on the railroads during the winter months, and rode the rodeo circuit during the summer. He was one of a handful of African Americans to make his mark in rodeo history. He died in a bronc riding accident in Bozeman, Montana in 1930, when his foot got caught in a stirrup. I found one oblique reference that called that accident “suspicious.”

Several sources had that much information. Interesting, but not quite enough to make a story. Then it occurred to me that Thompson was only the beginning of the story.

Tracy Thompson was the father of Idaho civil rights activist Idaho Purce. Idaho Purce is the matriarch of a family of five accomplished siblings, including Les Purce, who in 1973 at age 27, became the first black elected official in Idaho, serving on the Pocatello City Council. He served as mayor of Pocatello in 1976 and 1977. Purce served as director of the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare and the Idaho Department of Administration under Governor John Evans. After his government service, Dr. Purce became vice president of Extended University Affairs and Dean of Extended Academic Programs at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington. He then served as president of Evergreen State College, in Olympia, Washington from 2000 to 2015.

So, the legacy of bronc rider Tracy Thompson lasted a lot more than eight seconds.

Champion bronc rider Tracy Thompson. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Champion bronc rider Tracy Thompson. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Tracy Thompson was a homesteader in Arimo before moving to Pocatello in 1919. He worked on the railroads during the winter months, and rode the rodeo circuit during the summer. He was one of a handful of African Americans to make his mark in rodeo history. He died in a bronc riding accident in Bozeman, Montana in 1930, when his foot got caught in a stirrup. I found one oblique reference that called that accident “suspicious.”

Several sources had that much information. Interesting, but not quite enough to make a story. Then it occurred to me that Thompson was only the beginning of the story.

Tracy Thompson was the father of Idaho civil rights activist Idaho Purce. Idaho Purce is the matriarch of a family of five accomplished siblings, including Les Purce, who in 1973 at age 27, became the first black elected official in Idaho, serving on the Pocatello City Council. He served as mayor of Pocatello in 1976 and 1977. Purce served as director of the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare and the Idaho Department of Administration under Governor John Evans. After his government service, Dr. Purce became vice president of Extended University Affairs and Dean of Extended Academic Programs at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington. He then served as president of Evergreen State College, in Olympia, Washington from 2000 to 2015.

So, the legacy of bronc rider Tracy Thompson lasted a lot more than eight seconds.

Champion bronc rider Tracy Thompson. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Champion bronc rider Tracy Thompson. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on October 08, 2018 05:00

October 7, 2018

Idaho's Oldest Counties

People were soooo determined to use the name “Idaho” for something that it now seems almost inevitable. As you probably know, the name was also considered for Colorado, and Montana territories. Did you know that a county in Washington Territory had the name, too?

Idaho County, Washington Territory was created on December 20, 1861. It was named after the steamboat Idaho. You might have missed that because that county ended up in the new Idaho Territory in 1863 when the boundaries were drawn. Nez Perce and Shoshone counties were also originally counties in Washington Territory for a short time.

If you want to step back a few years, all of you living in Idaho today would have been living in either Walla Walla County, Washington Territory, or Skamania County, Washington Territory. They were created in 1854. The former included all of present day Idaho above the 46th parallel, and the latter the rest of it.

Idaho County, Washington Territory was created on December 20, 1861. It was named after the steamboat Idaho. You might have missed that because that county ended up in the new Idaho Territory in 1863 when the boundaries were drawn. Nez Perce and Shoshone counties were also originally counties in Washington Territory for a short time.

If you want to step back a few years, all of you living in Idaho today would have been living in either Walla Walla County, Washington Territory, or Skamania County, Washington Territory. They were created in 1854. The former included all of present day Idaho above the 46th parallel, and the latter the rest of it.

Published on October 07, 2018 04:30

October 6, 2018

A Modest Garden

In 1863 William J. McConnell and John H. Porter started a modest gardening business along a tributary of the Payette River, now called Porter Creek, not far from Horseshoe Bend in a mining area called Jerusalem. They had in mind selling produce to miners and settlers.

McConnell remembered one of their first gardening successes in a letter to the Idaho Statesman on January 2, 1916, “Four weeks after planting our onion sets we pulled them all, one Sabbath morning, and tied them in bunches, one dozen in a bunch. There proved to be one hundred bunches. I packed them into Placerville the same day and sold them for $1 a bunch as rapidly as I could hand them out. They were the first green vegetables offered in the market. Early beets and turnips came in a little later, bringing in the open market 45 cents per pound, tops and all, the tops making most excellent greens. Green corn was marketed at $2 per dozen ears; cucumbers, $2 per dozen; tomatoes, 35 cents per pound; potatoes, 35 cents.”

The Porter/McConnell operation was one of several in that area growing vegetables. Crickets discovered their efforts and right away started pestering the farmers. In 1864 the infestation of the critters was worse. Then in 1865 they arrived in hordes.

“At first the crickets [yes, probably the ones known today as Mormon crickets] while young did not seem to relish the growing wheat,” McConnell wrote,” but they took kindly to our barley, and the onions they considered a luxury. They not only ate the tops but they stood on their heads and explored the pith, They attacked the wheat when it was beginning to head and in three days it was utterly destroyed. Fortunately we were well supplied with water, and employing a force of men we constructed a ditch around the field where we had planted our potatoes, corn and vines, and by keeping it continually patrolled we managed to save that portion of our crop, but our neighbors were less fortunate, and we were the only gardeners who had vegetables to deliver from Jerusalem that year, consequently the others became discouraged and sold their holdings for what they were offered and abandoned the country.”

Porter inherited a farm in Canada in 1872 and left Idaho for good. McConnell started a general store in Moscow in 1884. When Idaho’s Constitutional convention took place, McConnell was the representative from Latah County. The ambitious gardener of 1863 became the third governor of Idaho 30 years later. He also served as one of the state’s first US senators in 1890 and 1891.

I talked about McConnell a bit in a previous post and plan on doing a future blog on his vigilante life. He was, let’s say, a well-rounded character.

Thanks to David Humphreys for pointing the way to this information.

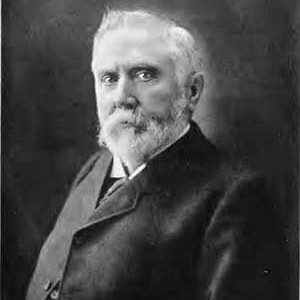

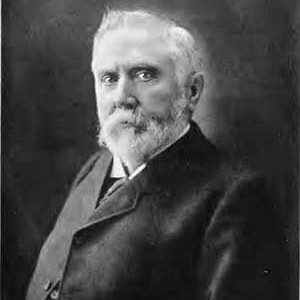

Gardener (and governor) William J. McConnell

Gardener (and governor) William J. McConnell  John Hughes Porter, 1874, taken shortly after he moved to Canada.

John Hughes Porter, 1874, taken shortly after he moved to Canada.

McConnell remembered one of their first gardening successes in a letter to the Idaho Statesman on January 2, 1916, “Four weeks after planting our onion sets we pulled them all, one Sabbath morning, and tied them in bunches, one dozen in a bunch. There proved to be one hundred bunches. I packed them into Placerville the same day and sold them for $1 a bunch as rapidly as I could hand them out. They were the first green vegetables offered in the market. Early beets and turnips came in a little later, bringing in the open market 45 cents per pound, tops and all, the tops making most excellent greens. Green corn was marketed at $2 per dozen ears; cucumbers, $2 per dozen; tomatoes, 35 cents per pound; potatoes, 35 cents.”

The Porter/McConnell operation was one of several in that area growing vegetables. Crickets discovered their efforts and right away started pestering the farmers. In 1864 the infestation of the critters was worse. Then in 1865 they arrived in hordes.

“At first the crickets [yes, probably the ones known today as Mormon crickets] while young did not seem to relish the growing wheat,” McConnell wrote,” but they took kindly to our barley, and the onions they considered a luxury. They not only ate the tops but they stood on their heads and explored the pith, They attacked the wheat when it was beginning to head and in three days it was utterly destroyed. Fortunately we were well supplied with water, and employing a force of men we constructed a ditch around the field where we had planted our potatoes, corn and vines, and by keeping it continually patrolled we managed to save that portion of our crop, but our neighbors were less fortunate, and we were the only gardeners who had vegetables to deliver from Jerusalem that year, consequently the others became discouraged and sold their holdings for what they were offered and abandoned the country.”

Porter inherited a farm in Canada in 1872 and left Idaho for good. McConnell started a general store in Moscow in 1884. When Idaho’s Constitutional convention took place, McConnell was the representative from Latah County. The ambitious gardener of 1863 became the third governor of Idaho 30 years later. He also served as one of the state’s first US senators in 1890 and 1891.

I talked about McConnell a bit in a previous post and plan on doing a future blog on his vigilante life. He was, let’s say, a well-rounded character.

Thanks to David Humphreys for pointing the way to this information.

Gardener (and governor) William J. McConnell

Gardener (and governor) William J. McConnell  John Hughes Porter, 1874, taken shortly after he moved to Canada.

John Hughes Porter, 1874, taken shortly after he moved to Canada.

Published on October 06, 2018 05:00

October 5, 2018

Intermountain Institute

The Intermountain Institute in Weiser was a boarding school established in the fall of 1899 to provide children who lived too far from a high school a chance at an education. The school’s motto was “An education and trade for every boy and girl who is willing to work for them.” Children worked five hours a day to help pay for their tuition, board, and room.

About 2,000 students got their education there before the ravages of the Great Depression forced it to close in 1933.

To architects, one feature of the campus buildings is worth note. All but one of the structures, a carriage house, were made of reinforced cast concrete. Concrete was a common building material in early Idaho, but it was used mostly in block form.

The buildings at the Intermountain Institute still had some style. The surfaces of the neo-classical buildings were scored to resemble masonry joints. This can be seen in the photo below of the laundry building under construction.

The Weiser School District used campus buildings until 1967 when a new high school was built. Hooker Hall, a three-story building with a five-story clock tower, became the county museum in the 1980s. In 1994 a fire caused much damage, and the building is still under renovation.

About 2,000 students got their education there before the ravages of the Great Depression forced it to close in 1933.

To architects, one feature of the campus buildings is worth note. All but one of the structures, a carriage house, were made of reinforced cast concrete. Concrete was a common building material in early Idaho, but it was used mostly in block form.

The buildings at the Intermountain Institute still had some style. The surfaces of the neo-classical buildings were scored to resemble masonry joints. This can be seen in the photo below of the laundry building under construction.

The Weiser School District used campus buildings until 1967 when a new high school was built. Hooker Hall, a three-story building with a five-story clock tower, became the county museum in the 1980s. In 1994 a fire caused much damage, and the building is still under renovation.

Published on October 05, 2018 04:30

October 4, 2018

Naming Credit for the Gem State

Sometimes one can make a claim to naming something that has little historical relevance. Why would I bring this up? We’ll get to that, but first let me illustrate the point from personal experience.

Back in the olden days when I was a radio announcer in Boise several of us were sitting around in an office trying to determine what we would call a radio station that had the irritating call letters, KJOT. K-Jot? Thumbs down to that. Someone called out “K-105.” There was already a K-106, so that seemed silly. I said, “How about J-105.” Brilliant. That became the name.

Let the kudos roll in for that one. The point is, that I happened to open my mouth first about a very limited number of choices. Big deal.

There is a claim, similarly not astonishing, regarding the naming of Idaho. It comes from Mrs. William H. Wallace, who was called “Lue.” William H. Wallace became the first territorial governor of Idaho. A letter from the son of Mrs. Wallace (below) tells of her fondness for a little girl who was named Idaho. When a discussion took place in the Wallace home regarding the name of the new territory being formed from part of Washington Territory, Mrs. Wallace spoke up, saying that her preference was Idaho. Only three names were under consideration, Idaho, Montana, and Lafayette, according to the letter. So, Mrs. Wallace may indeed have the distinction of “naming” Idaho.

Mrs. Wallace would likely have proclaimed the name was an Indian word meaning “Gem of the mountains.” That was a popular story at the time. It has since been quite thoroughly dashed by linguists. There is some evidence that George M. Willing, a lobbyist for the territory that would eventually become known as Colorado, coined the word in early 1860 as a substitute for naming the territory Jefferson. He may also have given birth to the “Gem of the mountains” definition.

People apparently liked the sound of it.A Columbia River steamer seems to be the first to use the name. It was launched on June 9, 1860, operating between the Cascades and The Dalles. On June 22 the Idaho Town Company was created in Colorado to get things rolling in a town that to this day is called Idaho Springs. Then, on December 20, 1861, the Washington Territorial Legislature named a new county Idaho County. It contained the gold mining areas of Warren and (fabulous) Florence.

Idaho had kicked around as a potential name for Colorado and Montana territories for some time. Those in Congress debating the territorial bills didn’t especially care which name went where. Idaho Territory was going to be called Montana Territory practically up to the last minute. Soon-to-be Territorial Governor Wallace’s own copy of the bill had the name Montana printed on it. That was scratched out with Idaho written in (see below) to reflect the late change.

So, who named Idaho? A lobbyist may have come up with the name, but Mrs. Wallace probably has as good a claim as anyone for attaching it to this place where we live. Linguists and historians may continue to debate where the name came from and what it means, but I think everyone is missing the point. It’s simply the name of my favorite state and as such holds enormous meaning.

Much of this story depends on the research of Merle W. Wells and an article he wrote for the spring 1958 issue of Idaho Yesterdays.

Above is Territorial Governor Wallace’s own copy of the Idaho Territorial Act with the printed name “Montana” corrected to “Idaho.”

Above is Territorial Governor Wallace’s own copy of the Idaho Territorial Act with the printed name “Montana” corrected to “Idaho.”  A letter written by the son of Territorial Governor and Mrs. Wallace in 1903 recounting his mother’s story about the naming Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

A letter written by the son of Territorial Governor and Mrs. Wallace in 1903 recounting his mother’s story about the naming Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

Back in the olden days when I was a radio announcer in Boise several of us were sitting around in an office trying to determine what we would call a radio station that had the irritating call letters, KJOT. K-Jot? Thumbs down to that. Someone called out “K-105.” There was already a K-106, so that seemed silly. I said, “How about J-105.” Brilliant. That became the name.

Let the kudos roll in for that one. The point is, that I happened to open my mouth first about a very limited number of choices. Big deal.

There is a claim, similarly not astonishing, regarding the naming of Idaho. It comes from Mrs. William H. Wallace, who was called “Lue.” William H. Wallace became the first territorial governor of Idaho. A letter from the son of Mrs. Wallace (below) tells of her fondness for a little girl who was named Idaho. When a discussion took place in the Wallace home regarding the name of the new territory being formed from part of Washington Territory, Mrs. Wallace spoke up, saying that her preference was Idaho. Only three names were under consideration, Idaho, Montana, and Lafayette, according to the letter. So, Mrs. Wallace may indeed have the distinction of “naming” Idaho.

Mrs. Wallace would likely have proclaimed the name was an Indian word meaning “Gem of the mountains.” That was a popular story at the time. It has since been quite thoroughly dashed by linguists. There is some evidence that George M. Willing, a lobbyist for the territory that would eventually become known as Colorado, coined the word in early 1860 as a substitute for naming the territory Jefferson. He may also have given birth to the “Gem of the mountains” definition.

People apparently liked the sound of it.A Columbia River steamer seems to be the first to use the name. It was launched on June 9, 1860, operating between the Cascades and The Dalles. On June 22 the Idaho Town Company was created in Colorado to get things rolling in a town that to this day is called Idaho Springs. Then, on December 20, 1861, the Washington Territorial Legislature named a new county Idaho County. It contained the gold mining areas of Warren and (fabulous) Florence.

Idaho had kicked around as a potential name for Colorado and Montana territories for some time. Those in Congress debating the territorial bills didn’t especially care which name went where. Idaho Territory was going to be called Montana Territory practically up to the last minute. Soon-to-be Territorial Governor Wallace’s own copy of the bill had the name Montana printed on it. That was scratched out with Idaho written in (see below) to reflect the late change.

So, who named Idaho? A lobbyist may have come up with the name, but Mrs. Wallace probably has as good a claim as anyone for attaching it to this place where we live. Linguists and historians may continue to debate where the name came from and what it means, but I think everyone is missing the point. It’s simply the name of my favorite state and as such holds enormous meaning.

Much of this story depends on the research of Merle W. Wells and an article he wrote for the spring 1958 issue of Idaho Yesterdays.

Above is Territorial Governor Wallace’s own copy of the Idaho Territorial Act with the printed name “Montana” corrected to “Idaho.”

Above is Territorial Governor Wallace’s own copy of the Idaho Territorial Act with the printed name “Montana” corrected to “Idaho.”  A letter written by the son of Territorial Governor and Mrs. Wallace in 1903 recounting his mother’s story about the naming Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

A letter written by the son of Territorial Governor and Mrs. Wallace in 1903 recounting his mother’s story about the naming Idaho. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's digital collection.

Published on October 04, 2018 05:00

October 3, 2018

Gowen Field

Gowen Field in Boise is much in the news these days, because it is under consideration to be one of the home fields for the Lockhead Martin F-35A Joint Strike Force Fighters. The jets would replace the A-10 “Warthogs” currently flown by the National Guard in Boise.

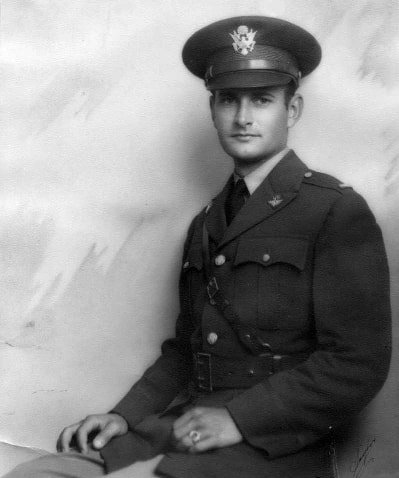

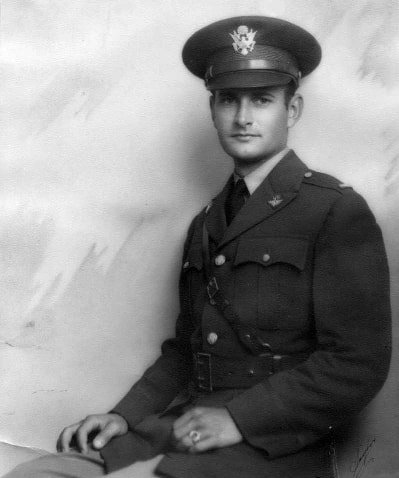

Setting aside that debate, today we’re going to look at the history of the name, Gowen Field.

At first, military officials didn’t think the air base could be named at all, because it was leased property not owned by the military. A new interpretation of regulations set those concerns aside, and in June of 1941 the Field Naming Board in Washington, D.C. began deliberating.

There were three names under consideration, each to potentially honor Air Corps members from Idaho who had lost their lives. They were Col. Lawrence F. Stone, who was killed may 25, 1940; First Lt. Paul R. Gowen, who was killed July 11 1938; and Second Lt. R. W. Merrick, who was killed Nov. 20, 1932.

Speculation at the time was that it would be named Stone Field, because he was the highest-ranking officer of the three under consideration.

When the Field Naming Board announced their selection, it was Lt. Gowen who was honored. Gowen was a native of Caldwell who had spent two years at the University of Idaho before transferring to the Military Academy a West Point in 1929. He was a Rhodes Scholar candidate and once applied for a patent for a fuel consumption indicator. The patent was awarded after his death.

Gowen was a flight instructor who had one aerial brush with death in Louisiana in 1937. He and a student were flying a BT-2 Army Trainer when a dust storm kicked up. They circled looking for a place to land without success. When their fuel ran out Gowen ordered his student to parachute from the plane. The student jumped and Gowen followed. Neither was hurt.

It was a dead engine in a twin-engine B-10B that cost Gowen his life. He tried to bring the damage airplane back to Albrook Field in the Panama Canal Zone but couldn’t keep it in the air long enough. The plane crashed into the jungle, killing Lt. Gowen. Two passengers were injured, but survived. Lt. Paul R. Gowen was buried with full military honors at the Canyon Hill Cemetery in Caldwell. He was 29.

The military Gowen Field was officially named in 1941. In September of 1970, the Boise Air Terminal also officially adopted the name. First Lt. Paul R. Gowen.

First Lt. Paul R. Gowen.

Setting aside that debate, today we’re going to look at the history of the name, Gowen Field.

At first, military officials didn’t think the air base could be named at all, because it was leased property not owned by the military. A new interpretation of regulations set those concerns aside, and in June of 1941 the Field Naming Board in Washington, D.C. began deliberating.

There were three names under consideration, each to potentially honor Air Corps members from Idaho who had lost their lives. They were Col. Lawrence F. Stone, who was killed may 25, 1940; First Lt. Paul R. Gowen, who was killed July 11 1938; and Second Lt. R. W. Merrick, who was killed Nov. 20, 1932.

Speculation at the time was that it would be named Stone Field, because he was the highest-ranking officer of the three under consideration.

When the Field Naming Board announced their selection, it was Lt. Gowen who was honored. Gowen was a native of Caldwell who had spent two years at the University of Idaho before transferring to the Military Academy a West Point in 1929. He was a Rhodes Scholar candidate and once applied for a patent for a fuel consumption indicator. The patent was awarded after his death.

Gowen was a flight instructor who had one aerial brush with death in Louisiana in 1937. He and a student were flying a BT-2 Army Trainer when a dust storm kicked up. They circled looking for a place to land without success. When their fuel ran out Gowen ordered his student to parachute from the plane. The student jumped and Gowen followed. Neither was hurt.

It was a dead engine in a twin-engine B-10B that cost Gowen his life. He tried to bring the damage airplane back to Albrook Field in the Panama Canal Zone but couldn’t keep it in the air long enough. The plane crashed into the jungle, killing Lt. Gowen. Two passengers were injured, but survived. Lt. Paul R. Gowen was buried with full military honors at the Canyon Hill Cemetery in Caldwell. He was 29.

The military Gowen Field was officially named in 1941. In September of 1970, the Boise Air Terminal also officially adopted the name.

First Lt. Paul R. Gowen.

First Lt. Paul R. Gowen.

Published on October 03, 2018 04:30

October 2, 2018

A Job No One Wanted

In the most recent primary election in Idaho, there were five serious candidates for governor and several not-so-serious candidates. Altogether the candidates spent more than $11 million to get the coveted job. That job was not always so coveted.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed five men to the office of territorial governor of Idaho. The first two of them accepted, then decided to take more attractive appointments. Grant’s third choice rejected the appointment outright. The fourth choice, Thomas M. Bowen accepted Grant’s appointment and struck out for Idaho. He spent all of a week in the territory before resigning.

Grant’s fifth choice for governor was Thomas W. Bennett, who had been a brigadier general on the Union side in the Civil War, and who had served two years as the mayor of Richmond, Indiana.

Idaho Territory’s Secretary of State, Eward J. Curtis, had been the acting territorial governor for a year, when the December 23, 1871 Idaho Statesman ran a short article speculating why the new governor, Thomas Bennett hadn’t shown up yet in Boise. Was there an issue with his confirmation? A snow blockade? After losing four other potential governors, the paper asked, “Does not this thing begin to look a little like a farce?”

Happily, the paper was reporting about a month later that the governor was headed up to Idaho City to “reconnoiter among the Idahoites a few days.” One more thing we can thank our stars for is that “Idahoites” did not become the standard of usage when referring to someone living in Idaho.

By most accounts, Bennett was a competent governor. He served the territory from 1871 to 1875. He won the election for Congressional delegate for Idaho Territory, and served in that capacity until June 1876, when a recount gave the 1874 election to his opponent, Stephen Fenn. Bennett moved back to his native Indiana when his Congressional office went sour. He died there on February 2, 1893.

Thomas W. Bennett, Idaho territorial governor 1871-1875.

Thomas W. Bennett, Idaho territorial governor 1871-1875.

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed five men to the office of territorial governor of Idaho. The first two of them accepted, then decided to take more attractive appointments. Grant’s third choice rejected the appointment outright. The fourth choice, Thomas M. Bowen accepted Grant’s appointment and struck out for Idaho. He spent all of a week in the territory before resigning.

Grant’s fifth choice for governor was Thomas W. Bennett, who had been a brigadier general on the Union side in the Civil War, and who had served two years as the mayor of Richmond, Indiana.

Idaho Territory’s Secretary of State, Eward J. Curtis, had been the acting territorial governor for a year, when the December 23, 1871 Idaho Statesman ran a short article speculating why the new governor, Thomas Bennett hadn’t shown up yet in Boise. Was there an issue with his confirmation? A snow blockade? After losing four other potential governors, the paper asked, “Does not this thing begin to look a little like a farce?”

Happily, the paper was reporting about a month later that the governor was headed up to Idaho City to “reconnoiter among the Idahoites a few days.” One more thing we can thank our stars for is that “Idahoites” did not become the standard of usage when referring to someone living in Idaho.

By most accounts, Bennett was a competent governor. He served the territory from 1871 to 1875. He won the election for Congressional delegate for Idaho Territory, and served in that capacity until June 1876, when a recount gave the 1874 election to his opponent, Stephen Fenn. Bennett moved back to his native Indiana when his Congressional office went sour. He died there on February 2, 1893.

Thomas W. Bennett, Idaho territorial governor 1871-1875.

Thomas W. Bennett, Idaho territorial governor 1871-1875.

Published on October 02, 2018 05:00

September 30, 2018

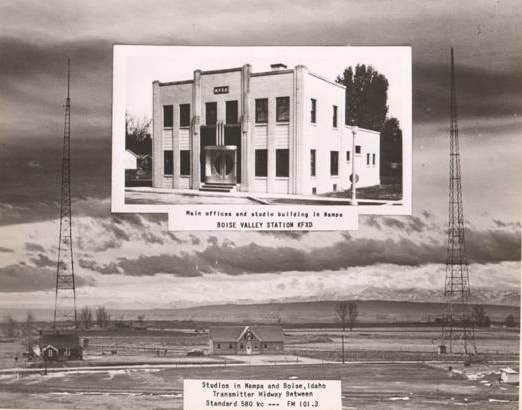

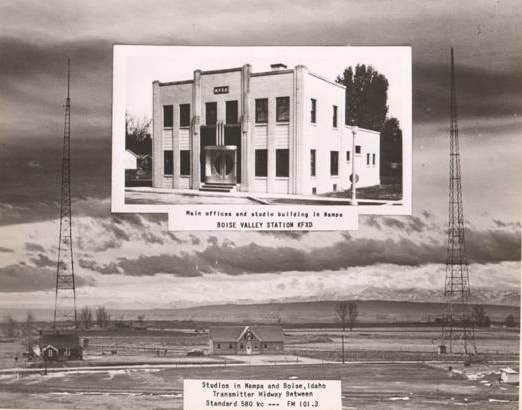

A Little Slice of History: KFXD Radio

I've begun doing a regular column for the Idaho Press. Each column will be similar to what you're used to seeing on Speaking of Idaho, though usually a little longer. I'd like to run those columns as a blog post the day after they appear, starting with this one today. Please click here to access the column.

Published on September 30, 2018 07:39

September 29, 2018

Dogcatchers

Today’s post is about dogcatchers in Idaho history. It’s not a subject that gets a lot of attention, and this post will largely continue that tradition. I just did a word search through a couple of Idaho newspaper databases to see if anything interesting might come up.

I have more dogs than are strictly necessary (three). I keep them on leash, pick up after them, license them regularly, etc. So, this notice in the Idaho Statesman from June 10, 1911 caught my eye. It was datelined Nampa. “The dogcatcher is abroad in this city and acting under the mandates of the city council, urged to duty by the mayor and supported by the police department, a special officer has been detailed to enforce the law relative to taxation on dogs. The tax price is $3.50 for male and $5 for female dogs and any dog not wearing the tax collar will be summarily dispatched to happy hunting grounds after a short campaign in which each dog owner will have opportunity to pay up.”

This was apparently written in the days when it cost extra to insert an occasional period in a news story.

Several Idaho papers, including the Elmore Bulletin, carried a story about dogcatchers in Chicago in 1893. The short version is that they chased this big dog all over the city before finally capturing him and determining that he was a wolf.

The Wood River Times had a short opinion related to dogs and those who ought to catch them: “There are too many dogs in town for the public good. They annoy horsemen, teams and especially ladies on horseback, create disturbance with every strange dog visiting the town, keep peaceable people awake of nights, infest restaurants and public places, and are an intolerable nuisance. The dog-catchers should be started out.”

Stories about dogcatchers were often played for humor. In 1934 the Statesman ran the headline “Boise Mutts Yap Joyfully As Council Cans Dogcatcher.” It was a temporary budget move.

There were about as many stories intimating that someone couldn’t get elected dogcatcher as there were legitimate stories about dogcatchers. So, they may be able to catch dogs, but one thing dogcatchers can’t catch is a break.

This is Stitch, the middle dog in the Just pack.

This is Stitch, the middle dog in the Just pack.

I have more dogs than are strictly necessary (three). I keep them on leash, pick up after them, license them regularly, etc. So, this notice in the Idaho Statesman from June 10, 1911 caught my eye. It was datelined Nampa. “The dogcatcher is abroad in this city and acting under the mandates of the city council, urged to duty by the mayor and supported by the police department, a special officer has been detailed to enforce the law relative to taxation on dogs. The tax price is $3.50 for male and $5 for female dogs and any dog not wearing the tax collar will be summarily dispatched to happy hunting grounds after a short campaign in which each dog owner will have opportunity to pay up.”

This was apparently written in the days when it cost extra to insert an occasional period in a news story.

Several Idaho papers, including the Elmore Bulletin, carried a story about dogcatchers in Chicago in 1893. The short version is that they chased this big dog all over the city before finally capturing him and determining that he was a wolf.

The Wood River Times had a short opinion related to dogs and those who ought to catch them: “There are too many dogs in town for the public good. They annoy horsemen, teams and especially ladies on horseback, create disturbance with every strange dog visiting the town, keep peaceable people awake of nights, infest restaurants and public places, and are an intolerable nuisance. The dog-catchers should be started out.”

Stories about dogcatchers were often played for humor. In 1934 the Statesman ran the headline “Boise Mutts Yap Joyfully As Council Cans Dogcatcher.” It was a temporary budget move.

There were about as many stories intimating that someone couldn’t get elected dogcatcher as there were legitimate stories about dogcatchers. So, they may be able to catch dogs, but one thing dogcatchers can’t catch is a break.

This is Stitch, the middle dog in the Just pack.

This is Stitch, the middle dog in the Just pack.

Published on September 29, 2018 05:00

September 28, 2018

Funny Firth

Today, I’d like your help in solving one of the enduring mysteries of life. At least, it’s an enduring mystery if you grew up in and around Firth. Shelley and Blackfoot, north and south of Firth, made US 91 their main street in the early days. The highway passes through Firth, too, but Firth’s Main Street is parallel to US 91, as if someone shoved the business district back away from the highway 50 feet. Over the years this has caused no end of confusion for people new to the town. For much of its history “Main Street” resembled a big, unstriped parking lot. People weren’t quite sure where they were supposed to be. It was terrific for cutting cookies in the winter when the whole thing froze over. Note to self: Watch out for the Texaco station.

This picture, courtesy of the Mike Fritz collection, shows Firth in the 1920s. South is at the top of the picture, more or less, as the highway runs north/south. Maybe there’s a clue here. You can see 91 paralleling the railroad tracks, then taking a little jog to allow for the train depot. On the right-hand side of the highway—west—you can see the utility lines punching through town. Those lines would have had a right of way. You can see the beginnings of Main Street to the right of those lines, like a frontage road. I’m wondering if the town and frontage road developed in a way that would avoid messing with those lines. Years later, maybe the lines went away and the town paved the abandoned right of way between Main and the highway.

I’d love to hear other theories, or better yet an explanation from someone with secondhand knowledge. First handers, sadly, would all be dead.

Can you identify any of the buildings in the picture below. I recognize the old train station, now gone. There is an elevator where the Firth Mill and Elevator is still, though it may have changed. The only building I can identify that is still in existence is the Corgatelli Building, almost in the center of the photo. Firth residents today would call it Collet's Bar. It was built sometime before 1913.

This photo of Firth circa 1920 is from the Mike Fritz collection.

This photo of Firth circa 1920 is from the Mike Fritz collection.

This picture, courtesy of the Mike Fritz collection, shows Firth in the 1920s. South is at the top of the picture, more or less, as the highway runs north/south. Maybe there’s a clue here. You can see 91 paralleling the railroad tracks, then taking a little jog to allow for the train depot. On the right-hand side of the highway—west—you can see the utility lines punching through town. Those lines would have had a right of way. You can see the beginnings of Main Street to the right of those lines, like a frontage road. I’m wondering if the town and frontage road developed in a way that would avoid messing with those lines. Years later, maybe the lines went away and the town paved the abandoned right of way between Main and the highway.

I’d love to hear other theories, or better yet an explanation from someone with secondhand knowledge. First handers, sadly, would all be dead.

Can you identify any of the buildings in the picture below. I recognize the old train station, now gone. There is an elevator where the Firth Mill and Elevator is still, though it may have changed. The only building I can identify that is still in existence is the Corgatelli Building, almost in the center of the photo. Firth residents today would call it Collet's Bar. It was built sometime before 1913.

This photo of Firth circa 1920 is from the Mike Fritz collection.

This photo of Firth circa 1920 is from the Mike Fritz collection.

Published on September 28, 2018 05:00