Rick Just's Blog, page 184

October 7, 2019

Naming Gowen Field

Gowen Field in Boise is much in the news these days, because it is under consideration to be one of the home fields for the Lockhead Martin F-35A Joint Strike Force Fighters. The jets would replace the A-10 “Warthogs” currently flown by the National Guard in Boise.

Setting aside that debate, today we’re going to look at the history of the name, Gowen Field.

At first, military officials didn’t think the air base could be named at all, because it was leased property not owned by the military. A new interpretation of regulations set those concerns aside, and in June of 1941 the Field Naming Board in Washington, D.C. began deliberating.

There were three names under consideration, each to potentially honor Air Corps members from Idaho who had lost their lives. They were Col. Lawrence F. Stone, who was killed may 25, 1940; First Lt. Paul R. Gowen, who was killed July 11 1938; and Second Lt. R. W. Merrick, who was killed Nov. 20, 1932.

Speculation at the time was that it would be named Stone Field, because he was the highest-ranking officer of the three under consideration.

When the Field Naming Board announced their selection, it was Lt. Gowen who was honored. Gowen was a native of Caldwell who had spent two years at the University of Idaho before transferring to the Military Academy a West Point in 1929. He was a Rhodes Scholar candidate and once applied for a patent for a fuel consumption indicator. The patent was awarded after his death.

Gowen was a flight instructor who had one aerial brush with death in Louisiana in 1937. He and a student were flying a BT-2 Army Trainer when a dust storm kicked up. They circled looking for a place to land without success. When their fuel ran out Gowen ordered his student to parachute from the plane. The student jumped and Gowen followed. Neither was hurt.

It was a dead engine in a twin-engine B-10B that cost Gowen his life. He tried to bring the damage airplane back to Albrook Field in the Panama Canal Zone but couldn’t keep it in the air long enough. The plane crashed into the jungle, killing Lt. Gowen. Two passengers were injured, but survived. Lt. Paul R. Gowen was buried with full military honors at the Canyon Hill Cemetery in Caldwell. He was 29.

The military Gowen Field was officially named in 1941. In September of 1970, the Boise Air Terminal also officially adopted the name. First Lt. Paul R. Gowen,

First Lt. Paul R. Gowen,

Setting aside that debate, today we’re going to look at the history of the name, Gowen Field.

At first, military officials didn’t think the air base could be named at all, because it was leased property not owned by the military. A new interpretation of regulations set those concerns aside, and in June of 1941 the Field Naming Board in Washington, D.C. began deliberating.

There were three names under consideration, each to potentially honor Air Corps members from Idaho who had lost their lives. They were Col. Lawrence F. Stone, who was killed may 25, 1940; First Lt. Paul R. Gowen, who was killed July 11 1938; and Second Lt. R. W. Merrick, who was killed Nov. 20, 1932.

Speculation at the time was that it would be named Stone Field, because he was the highest-ranking officer of the three under consideration.

When the Field Naming Board announced their selection, it was Lt. Gowen who was honored. Gowen was a native of Caldwell who had spent two years at the University of Idaho before transferring to the Military Academy a West Point in 1929. He was a Rhodes Scholar candidate and once applied for a patent for a fuel consumption indicator. The patent was awarded after his death.

Gowen was a flight instructor who had one aerial brush with death in Louisiana in 1937. He and a student were flying a BT-2 Army Trainer when a dust storm kicked up. They circled looking for a place to land without success. When their fuel ran out Gowen ordered his student to parachute from the plane. The student jumped and Gowen followed. Neither was hurt.

It was a dead engine in a twin-engine B-10B that cost Gowen his life. He tried to bring the damage airplane back to Albrook Field in the Panama Canal Zone but couldn’t keep it in the air long enough. The plane crashed into the jungle, killing Lt. Gowen. Two passengers were injured, but survived. Lt. Paul R. Gowen was buried with full military honors at the Canyon Hill Cemetery in Caldwell. He was 29.

The military Gowen Field was officially named in 1941. In September of 1970, the Boise Air Terminal also officially adopted the name.

First Lt. Paul R. Gowen,

First Lt. Paul R. Gowen,

Published on October 07, 2019 14:00

October 6, 2019

The Fortune Teller's Fortune

Countless people have tried to find the loot from what is sometimes called the “Robbers’ Roost Holdup,” somewhere between $40,000 and $86,000 worth. Note those were 1865 dollars, which would be worth north of $2 million today. Calculating just where that gold from a stagecoach robbery might be buried has kept many a treasure hunter up at night.

In 1929 there was only one man alive who knew where the gold was. At least, that’s what A.B. Meyer told Agnes Schwabe of McCammon. The original robbery took place not far from McCammon. The 1929 theft took place in Mrs. Schwabe’s house.

Meyer received his unique knowledge by way of clairvoyancy. During a séance he told Mrs. Schwabe all about the hidden loot. She was excited enough to give Meyer the $500 he needed for “excavations.” Once he had the money he took a hurried departure.

The fortune teller, who worked out of Pocatello, was also exceedingly helpful to Mrs. H.C. Lyon Harris of that city. It was fame, not fortune, that lured Mrs. Harris. Meyer promised that he could use his clairvoyancy, somehow, to secure a motion picture contract for her daughter. When the seer skipped with Mrs. Harris’ $250, she joined the complaint of Mrs. Schwabe and an arrest warrant was issued. Meanwhile, Meyer had convinced an American Falls man to give him $200 on the promise of a job at Henry Ford’s marvelous, and fictional, mine in Idaho.

A.B. Meyer, which was actually the alias of Sam Stevens, was caught in Salem, Oregon and brought back to Idaho for trial. Stevens was convicted of fraud and appealed his conviction to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court looked into their crystal ball and envisioned him spending the next 5 to 14 years in prison.

Which he didn’t.

Eighteen months after he entered the Idaho State Penitentiary, Sam Stevens, aka A.B. Meyer, was pardoned by the board of pardons and paroles and told to leave the state and join his wife and child in Colorado.

But he wasn’t quite done with fortune telling.

“Pardoned Prison Clairvoyant Reveals Future for Warden,” read the headline on the front page of the July 9, 1931 Idaho Statesman. Stevens left a note for Warden R.E. Thomas that predicted that Governor C. Ben Ross would be re-elected and that the warden would be reappointed. Ross was re-elected. Thomas was not reappointed. So, batting .500. The note also had something of an apology because Stevens had “a presentiment about Lyda Southard leaving but (was) afraid to reveal it for fear you would think me silly.” Southard had escaped, but that’s another story.

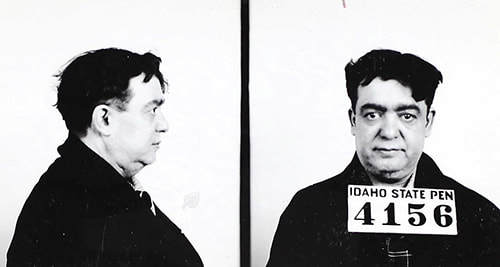

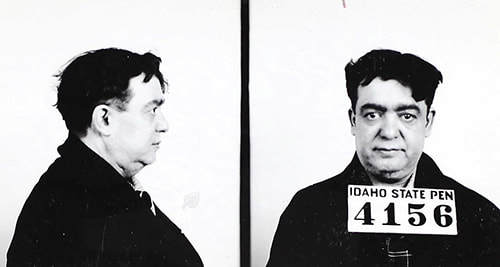

Stevens’ prison records describe him as just short of 5’ 4” and 159 pounds. He was short, “very stout,” with bad teeth and a double chin. His listed occupation was Fortune Teller.

The fortune teller A.B. Meyer, aka Sam Stevens, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society penitentiary collection.

The fortune teller A.B. Meyer, aka Sam Stevens, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society penitentiary collection.

In 1929 there was only one man alive who knew where the gold was. At least, that’s what A.B. Meyer told Agnes Schwabe of McCammon. The original robbery took place not far from McCammon. The 1929 theft took place in Mrs. Schwabe’s house.

Meyer received his unique knowledge by way of clairvoyancy. During a séance he told Mrs. Schwabe all about the hidden loot. She was excited enough to give Meyer the $500 he needed for “excavations.” Once he had the money he took a hurried departure.

The fortune teller, who worked out of Pocatello, was also exceedingly helpful to Mrs. H.C. Lyon Harris of that city. It was fame, not fortune, that lured Mrs. Harris. Meyer promised that he could use his clairvoyancy, somehow, to secure a motion picture contract for her daughter. When the seer skipped with Mrs. Harris’ $250, she joined the complaint of Mrs. Schwabe and an arrest warrant was issued. Meanwhile, Meyer had convinced an American Falls man to give him $200 on the promise of a job at Henry Ford’s marvelous, and fictional, mine in Idaho.

A.B. Meyer, which was actually the alias of Sam Stevens, was caught in Salem, Oregon and brought back to Idaho for trial. Stevens was convicted of fraud and appealed his conviction to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court looked into their crystal ball and envisioned him spending the next 5 to 14 years in prison.

Which he didn’t.

Eighteen months after he entered the Idaho State Penitentiary, Sam Stevens, aka A.B. Meyer, was pardoned by the board of pardons and paroles and told to leave the state and join his wife and child in Colorado.

But he wasn’t quite done with fortune telling.

“Pardoned Prison Clairvoyant Reveals Future for Warden,” read the headline on the front page of the July 9, 1931 Idaho Statesman. Stevens left a note for Warden R.E. Thomas that predicted that Governor C. Ben Ross would be re-elected and that the warden would be reappointed. Ross was re-elected. Thomas was not reappointed. So, batting .500. The note also had something of an apology because Stevens had “a presentiment about Lyda Southard leaving but (was) afraid to reveal it for fear you would think me silly.” Southard had escaped, but that’s another story.

Stevens’ prison records describe him as just short of 5’ 4” and 159 pounds. He was short, “very stout,” with bad teeth and a double chin. His listed occupation was Fortune Teller.

The fortune teller A.B. Meyer, aka Sam Stevens, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society penitentiary collection.

The fortune teller A.B. Meyer, aka Sam Stevens, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society penitentiary collection.

Published on October 06, 2019 04:00

October 5, 2019

In the Dog House Now

Today’s post is about dogcatchers in Idaho history. It’s not a subject that gets a lot of attention, and this post will largely continue that tradition. I just did a word search through a couple of Idaho newspaper databases to see if anything interesting might come up.

I have more dogs than are strictly necessary (three). I keep them on leash, pick up after them, license them regularly, etc. So, this notice in the Idaho Statesman from June 10, 1911 caught my eye. It was datelined Nampa. “The dogcatcher is abroad in this city and acting under the mandates of the city council, urged to duty by the mayor and supported by the police department, a special officer has been detailed to enforce the law relative to taxation on dogs. The tax price is $3.50 for male and $5 for female dogs and any dog not wearing the tax collar will be summarily dispatched to happy hunting grounds after a short campaign in which each dog owner will have opportunity to pay up.”

This was apparently written in the days when it cost extra to insert an occasional period in a news story.

Several Idaho papers, including the Elmore Bulletin, carried a story about dogcatchers in Chicago in 1893. The short version is that they chased this big dog all over the city before finally capturing him and determining that he was a wolf.

The Wood River Times had a short opinion related to dogs and those who ought to catch them: “There are too many dogs in town for the public good. They annoy horsemen, teams and especially ladies on horseback, create disturbance with every strange dog visiting the town, keep peaceable people awake of nights, infest restaurants and public places, and are an intolerable nuisance. The dog-catchers should be started out.”

Stories about dogcatchers were often played for humor. In 1934 the Statesman ran the headline “Boise Mutts Yap Joyfully As Council Cans Dogcatcher.” It was a temporary budget move.

There were about as many stories intimating that someone couldn’t get elected dogcatcher as there were legitimate stories about dogcatchers. So, they may be able to catch dogs, but one thing dogcatchers can’t catch is a break.

Stitch, one of my semi-official history mascots.

Stitch, one of my semi-official history mascots.

I have more dogs than are strictly necessary (three). I keep them on leash, pick up after them, license them regularly, etc. So, this notice in the Idaho Statesman from June 10, 1911 caught my eye. It was datelined Nampa. “The dogcatcher is abroad in this city and acting under the mandates of the city council, urged to duty by the mayor and supported by the police department, a special officer has been detailed to enforce the law relative to taxation on dogs. The tax price is $3.50 for male and $5 for female dogs and any dog not wearing the tax collar will be summarily dispatched to happy hunting grounds after a short campaign in which each dog owner will have opportunity to pay up.”

This was apparently written in the days when it cost extra to insert an occasional period in a news story.

Several Idaho papers, including the Elmore Bulletin, carried a story about dogcatchers in Chicago in 1893. The short version is that they chased this big dog all over the city before finally capturing him and determining that he was a wolf.

The Wood River Times had a short opinion related to dogs and those who ought to catch them: “There are too many dogs in town for the public good. They annoy horsemen, teams and especially ladies on horseback, create disturbance with every strange dog visiting the town, keep peaceable people awake of nights, infest restaurants and public places, and are an intolerable nuisance. The dog-catchers should be started out.”

Stories about dogcatchers were often played for humor. In 1934 the Statesman ran the headline “Boise Mutts Yap Joyfully As Council Cans Dogcatcher.” It was a temporary budget move.

There were about as many stories intimating that someone couldn’t get elected dogcatcher as there were legitimate stories about dogcatchers. So, they may be able to catch dogs, but one thing dogcatchers can’t catch is a break.

Stitch, one of my semi-official history mascots.

Stitch, one of my semi-official history mascots.

Published on October 05, 2019 04:00

October 4, 2019

Tenuous Connections

So, I’m finalizing my first book in the Speaking of Idaho series. It will be called Symbols, Signs, and Songs, and it will be out in the next few weeks.

Lana Turner, pictured below in a publicity still for the 1966 film Madame X in which she starred, was not a singer. Yet, she’s included in the Songs section of my new book. What gives?

Turner, who was born Julia Jean Turner in Wallace, Idaho in 1921 was a Hollywood icon. All those apocryphal Hollywood “discovered in a soda shop” stories lead back to her. She was spotted at the Top Hat Malt Shop on Sunset Boulevard sipping a Coke while skipping a typing class at Hollywood High. The publisher of Hollywood Reporter did the spotting. She was not a singer, but staying with the rules of this book (which I make up as I go along), she is included because of the reference to the star from Idaho in the song “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” by Nina Simone, Natalie Cole, and others. Bonus tenuous connection: Singer Lana Del Ray took the Lana part of her stage name from Lana Turner. Director Mervyn LeRoy assigned the name Lana to Turner, who legally changed her name to match her film persona.

There are more solid Idaho song connections in the book, but I have a section on the more tenuous connections, such as Lana. Here are a couple more

Gary Puckett, lead singer of Gary Puckett and the Union Gap, graduated from Twin Falls High School in 1960. For a couple of years in the late sixties, the group blasted from AM radio antennae all over the country with hits like “Lady Willpower,” “Woman, Woman,” and “Over You.” Their biggest seller was “Young Girl,” which made it to number two on the Billboard Hot 100. They got edged out for Best New Artist in the 1969 Grammy Awards by Jose Feliciano.

Glenn Close, who has Emmys, Tonys, Golden Globes, and several Academy Award nominations probably doesn’t consider her performance as the lead singer of Up with People during the 1965 World Boy Scout Jamboree at Farragut State Park the high point of her career. Still, there you have it.

Lana Turner, pictured below in a publicity still for the 1966 film Madame X in which she starred, was not a singer. Yet, she’s included in the Songs section of my new book. What gives?

Turner, who was born Julia Jean Turner in Wallace, Idaho in 1921 was a Hollywood icon. All those apocryphal Hollywood “discovered in a soda shop” stories lead back to her. She was spotted at the Top Hat Malt Shop on Sunset Boulevard sipping a Coke while skipping a typing class at Hollywood High. The publisher of Hollywood Reporter did the spotting. She was not a singer, but staying with the rules of this book (which I make up as I go along), she is included because of the reference to the star from Idaho in the song “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” by Nina Simone, Natalie Cole, and others. Bonus tenuous connection: Singer Lana Del Ray took the Lana part of her stage name from Lana Turner. Director Mervyn LeRoy assigned the name Lana to Turner, who legally changed her name to match her film persona.

There are more solid Idaho song connections in the book, but I have a section on the more tenuous connections, such as Lana. Here are a couple more

Gary Puckett, lead singer of Gary Puckett and the Union Gap, graduated from Twin Falls High School in 1960. For a couple of years in the late sixties, the group blasted from AM radio antennae all over the country with hits like “Lady Willpower,” “Woman, Woman,” and “Over You.” Their biggest seller was “Young Girl,” which made it to number two on the Billboard Hot 100. They got edged out for Best New Artist in the 1969 Grammy Awards by Jose Feliciano.

Glenn Close, who has Emmys, Tonys, Golden Globes, and several Academy Award nominations probably doesn’t consider her performance as the lead singer of Up with People during the 1965 World Boy Scout Jamboree at Farragut State Park the high point of her career. Still, there you have it.

Published on October 04, 2019 04:00

October 3, 2019

Boise's Mikado 282

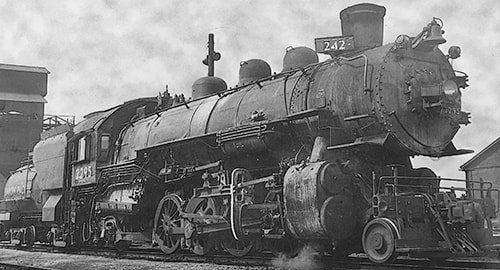

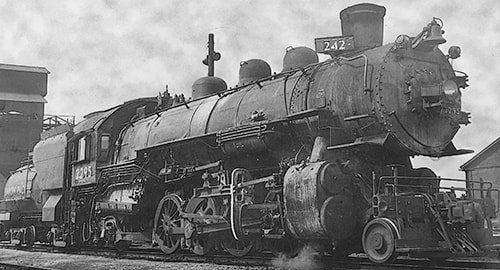

One of the most common locomotive engines during the heyday of steam was the Mikado. It was called the Mikado because many of the first engines were built for export to Japan. Railroad workers nicknamed the Mikados “Mike.” That’s why the one on display at the Boise Depot is called Big Mike.

They were giants. Big Mike is almost 82 feet long, counting its tender. It’s 15 feet 10 3/8 inches from the ground to the top of the stack, and the whole thing weighs 463,000 pounds before it takes on up to 17 tons of coal and 10,000 gallons of water.

They built the 14,000 Mikados from 1911 through 1944. Big Mike is a Mikado 282, which means it has eight big wheels underneath the locomotive with two smaller wheels in front and two in back.

Big Mike, or Engine No. 2295, was retired by Union Pacific and donated to the city of Boise in 1956. The locomotive was subsequently moved to the 3rd Street entrance to Julia Davis Park.

On Dec. 9, 2007, Big Mike—minus its tender—was moved to a new home on a siding east of the Boise Depot. Hundreds of people watched the move, which occurred at midnight on a cold winter's night. The tender, which carried water and fuel for the engine, was separated from the engine and had been moved on Dec. 6, 2007.

It’s well worth visiting the Boise Depot and Big Mike if you haven’t already done so.

They were giants. Big Mike is almost 82 feet long, counting its tender. It’s 15 feet 10 3/8 inches from the ground to the top of the stack, and the whole thing weighs 463,000 pounds before it takes on up to 17 tons of coal and 10,000 gallons of water.

They built the 14,000 Mikados from 1911 through 1944. Big Mike is a Mikado 282, which means it has eight big wheels underneath the locomotive with two smaller wheels in front and two in back.

Big Mike, or Engine No. 2295, was retired by Union Pacific and donated to the city of Boise in 1956. The locomotive was subsequently moved to the 3rd Street entrance to Julia Davis Park.

On Dec. 9, 2007, Big Mike—minus its tender—was moved to a new home on a siding east of the Boise Depot. Hundreds of people watched the move, which occurred at midnight on a cold winter's night. The tender, which carried water and fuel for the engine, was separated from the engine and had been moved on Dec. 6, 2007.

It’s well worth visiting the Boise Depot and Big Mike if you haven’t already done so.

Published on October 03, 2019 04:00

October 2, 2019

Bison Jumps

Bison jumps, or buffalo jumps, if you prefer, were an efficient way for the people indigenous to North America to obtain food in quantities not available in any other way. Several sites in the plains and in Montana are more famous and better studied, but Idaho has a bison jump that is worth a visit.

The Challis Bison Jump site is on property managed by the Bureau of Land Management near the visitor center for Land of the Yankee Fork State Park, which is just south of Challis at the junction of US 93 and State Highway 75.

How the Shoshoni drove the bison to the precipice may have varied. Before the arrival of horses tribal members probably snuck up on a herd on foot on three sides, making themselves known when they were close enough to startle the beasts, driving them forward and over the cliff. But they may also have used a “lure.”

Meriwether Lewis, writing in his journals about the method of Blackfeet Indians in present-day Montana, wrote, “one of the most active and fleet young men is selected and disguised in a robe of buffalo skin... he places himself at a distance between a herd of buffalo and a precipice proper for the purpose; the other Indians now surround the herd on the back and flanks and at a signal agreed on all show themselves at the same time moving forward towards the buffalo; the disguised Indian or decoy has taken care to place himself sufficiently near the buffalo to be noticed by them when they take to flight and running before them they follow him in full speed to the precipice; the Indian (decoy) in the mean time has taken care to secure himself in some cranny in the cliff... the part of the decoy I am informed is extremely dangerous.”

The Shoshoni may have used the Challis jump site for centuries, though by 1840 the bison were mostly gone. Once plains Indians acquired horses they began to prefer the method of surrounding the animals and running them in a circle while stabbing the beasts with long lances.

Some bison jump sites have yielded bones twenty and thirty feet deep indicating long use. Many bones have been excavated at the Challis site, though not nearly to that extent. Stone weapons and sites where they were made are also associated with the Challis Bison Jump. It was placed on the National Register of Historical Places in 1975.

The Challis Bison Jump.

The Challis Bison Jump.

The Challis Bison Jump site is on property managed by the Bureau of Land Management near the visitor center for Land of the Yankee Fork State Park, which is just south of Challis at the junction of US 93 and State Highway 75.

How the Shoshoni drove the bison to the precipice may have varied. Before the arrival of horses tribal members probably snuck up on a herd on foot on three sides, making themselves known when they were close enough to startle the beasts, driving them forward and over the cliff. But they may also have used a “lure.”

Meriwether Lewis, writing in his journals about the method of Blackfeet Indians in present-day Montana, wrote, “one of the most active and fleet young men is selected and disguised in a robe of buffalo skin... he places himself at a distance between a herd of buffalo and a precipice proper for the purpose; the other Indians now surround the herd on the back and flanks and at a signal agreed on all show themselves at the same time moving forward towards the buffalo; the disguised Indian or decoy has taken care to place himself sufficiently near the buffalo to be noticed by them when they take to flight and running before them they follow him in full speed to the precipice; the Indian (decoy) in the mean time has taken care to secure himself in some cranny in the cliff... the part of the decoy I am informed is extremely dangerous.”

The Shoshoni may have used the Challis jump site for centuries, though by 1840 the bison were mostly gone. Once plains Indians acquired horses they began to prefer the method of surrounding the animals and running them in a circle while stabbing the beasts with long lances.

Some bison jump sites have yielded bones twenty and thirty feet deep indicating long use. Many bones have been excavated at the Challis site, though not nearly to that extent. Stone weapons and sites where they were made are also associated with the Challis Bison Jump. It was placed on the National Register of Historical Places in 1975.

The Challis Bison Jump.

The Challis Bison Jump.

Published on October 02, 2019 04:00

October 1, 2019

Our State Tree

This Idaho state symbol is probably in your kitchen cupboard right now. The western white pine is an important tree for the timber industry. It's a durable, close-grained tree that is uniform in texture.

White pine is lightweight, seasons without warping, takes nails without splitting, and saws easily. That makes it a terrific tree for door and window frames, cabinets, and paneling. Oh yes, about the white pine that's in your cupboard right now--kitchen matches.

The western white pine does best in a cool and dry climate. Although it can grow at sea level, it prefers elevations of 2500 to 6000 feet. In Idaho, it grows mostly in the panhandle. A mature tree typically gets to be about 100 feet high.

A gregarious tree, the western white pine seems to prefer mixing with other common evergreens rather than in large stands of its own. One plant it would be better off not mixing with is the currant. A fungus called pine blister rust kills the pine, but it's only found where currants or gooseberries grow.

The western white pine was named the state tree of Idaho by the 1935 Legislature.

This photo is labeled as the “Largest Known White Pine.” How large? It was 207 feet tall, and its diameter was 6-feet 7-inches. It scaled at 29,800 board feet measure. The rings counted out at 425, so it was 425 years old when cut down in 1912. The live tree was located seven miles northwest of Bovill. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 78-37-158

This photo is labeled as the “Largest Known White Pine.” How large? It was 207 feet tall, and its diameter was 6-feet 7-inches. It scaled at 29,800 board feet measure. The rings counted out at 425, so it was 425 years old when cut down in 1912. The live tree was located seven miles northwest of Bovill. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 78-37-158

White pine is lightweight, seasons without warping, takes nails without splitting, and saws easily. That makes it a terrific tree for door and window frames, cabinets, and paneling. Oh yes, about the white pine that's in your cupboard right now--kitchen matches.

The western white pine does best in a cool and dry climate. Although it can grow at sea level, it prefers elevations of 2500 to 6000 feet. In Idaho, it grows mostly in the panhandle. A mature tree typically gets to be about 100 feet high.

A gregarious tree, the western white pine seems to prefer mixing with other common evergreens rather than in large stands of its own. One plant it would be better off not mixing with is the currant. A fungus called pine blister rust kills the pine, but it's only found where currants or gooseberries grow.

The western white pine was named the state tree of Idaho by the 1935 Legislature.

This photo is labeled as the “Largest Known White Pine.” How large? It was 207 feet tall, and its diameter was 6-feet 7-inches. It scaled at 29,800 board feet measure. The rings counted out at 425, so it was 425 years old when cut down in 1912. The live tree was located seven miles northwest of Bovill. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 78-37-158

This photo is labeled as the “Largest Known White Pine.” How large? It was 207 feet tall, and its diameter was 6-feet 7-inches. It scaled at 29,800 board feet measure. The rings counted out at 425, so it was 425 years old when cut down in 1912. The live tree was located seven miles northwest of Bovill. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 78-37-158

Published on October 01, 2019 04:00

September 30, 2019

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

By the way, if you're not seeing my posts every day, go to the Speaking of Idaho Facebook page and click on the button that says Following. Scroll down and click on See This First. It will now appear in you feed every day.

1). Marty Martin organized a fire in 1966. What was he burning?

A. Copies of The Boys of Boise.

B. Elvis Presley records.

C. Rolling Stones records.

D. Beatles records.

E. Copies of Lolita.

2). What record did Troy Powell and Ernie Walrath hold?

A. First to bicycle between Mountain Home and Boise.

B. They were the only subjects of a double hanging in Idaho.

C. They were Olympic doubles tennis champions from Idaho.

D. Tied for most goals in a Boise polo match.

E. They discovered the richest mine in Idaho.

3). What made the Howdy Pardner Drive-In unique?

A. It was the first to serve tater tots.

B. It was the first to serve finger steaks.

C. It had a stage on its roof where entertainers performed.

D. Its carhops wore ice skates.

E. There was a car show in the parking lot every Wednesday night.

4). December 7, 1937, was the day what took place?

A. A congressional potato competition between Idaho and Maine

B. The bombing of Pearl Harbor.

C. A race between an airplane and a motorcycle at the fairgrounds in Lewiston.

D. An earthquake near Soda Springs that measured 6.7 on the Richter Scale.

E. Sun Valley officially opened.

5) What is the official Idaho State Dance?

A. The Hokey Pokey.

B. The twist.

C. The foxtrot

D. The Tennessee Waltz.

E. The square dance.

Answers

Answers

1, D

2, B

3, C

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

By the way, if you're not seeing my posts every day, go to the Speaking of Idaho Facebook page and click on the button that says Following. Scroll down and click on See This First. It will now appear in you feed every day.

1). Marty Martin organized a fire in 1966. What was he burning?

A. Copies of The Boys of Boise.

B. Elvis Presley records.

C. Rolling Stones records.

D. Beatles records.

E. Copies of Lolita.

2). What record did Troy Powell and Ernie Walrath hold?

A. First to bicycle between Mountain Home and Boise.

B. They were the only subjects of a double hanging in Idaho.

C. They were Olympic doubles tennis champions from Idaho.

D. Tied for most goals in a Boise polo match.

E. They discovered the richest mine in Idaho.

3). What made the Howdy Pardner Drive-In unique?

A. It was the first to serve tater tots.

B. It was the first to serve finger steaks.

C. It had a stage on its roof where entertainers performed.

D. Its carhops wore ice skates.

E. There was a car show in the parking lot every Wednesday night.

4). December 7, 1937, was the day what took place?

A. A congressional potato competition between Idaho and Maine

B. The bombing of Pearl Harbor.

C. A race between an airplane and a motorcycle at the fairgrounds in Lewiston.

D. An earthquake near Soda Springs that measured 6.7 on the Richter Scale.

E. Sun Valley officially opened.

5) What is the official Idaho State Dance?

A. The Hokey Pokey.

B. The twist.

C. The foxtrot

D. The Tennessee Waltz.

E. The square dance.

Answers

Answers1, D

2, B

3, C

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on September 30, 2019 04:00

September 29, 2019

The Tyee

Logging was THE industry around Priest Lake in the latter part of the 19th century and much of the 20th. Diamond Match Company cut a lot of Western white pine around the lake so that people all around the world could strike a match.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake, if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake, if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

Published on September 29, 2019 04:00

September 28, 2019

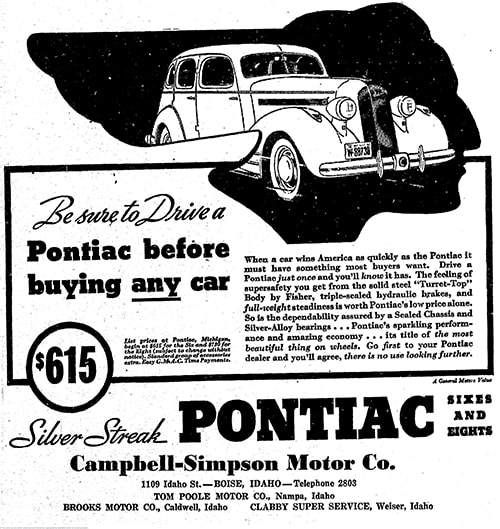

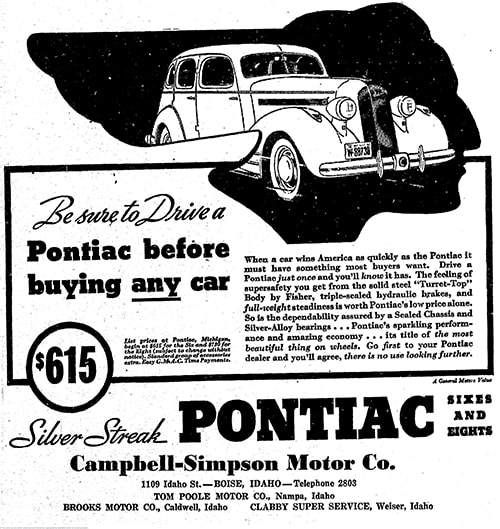

Licensing Drivers

If you’ve had the experience of waiting in line for several hours to obtain a driver’s license recently as thousands of Idahoans have, you probably thought it was a long wait. I feel your pain, because that wait awaits me this month. Perhaps we can all console ourselves with the knowledge that waiting a few hours to obtain a driver’s license in Idaho today is nothing compared with the long wait Idahoans had before there was even such a thing as a driver’s license in the state.

The first mention of a driver’s license for Idahoans that I could find was in an Idaho Statesman editorial on July 8, 1911. The paper was proposing a city driver’s license ordinance after the death of a young girl on the streets. She was killed by a streetcar. The Statesman called for licensing streetcar operators and operators of automobiles, as well.

Boise was behind at least one other Idaho city when it came to licensing. Those driving automobiles in Twin Falls in 1912 were reminded in the Twin Falls Times that they must take out a license to drive. It would cost them $1.

In 1917 the City of Boise passed an ordinance requiring livery drivers to purchase a license. The city council revoked at least a couple of licenses that year, one for drunk driving.

1924 was the first year a bill to require drivers to be licensed came up in the Idaho Legislature. One Statesman headline touted the “Examination of Drivers to Eliminate all Evils.” Requiring drivers to obtain a license was seen as a safety measure, not because they had to take a test, but because the state would then have the ability to take away a license from a driver who proved to be reckless. The bill went nowhere.

In 1927, the idea was back in the Idaho Legislature. National organizations were pushing for universal automobile legislation state by state. Idaho legislators then were about as ready to accept anything that smelled like federal government meddling as they are now. Nada on the driver’s license bill.

By 1928 there were 12 states requiring driver’s licenses. Only five of them required a test to obtain a license. That year the Idaho Statesman ran an article from a national motor club pointing out that “in all too many states, any boy or girl, any deaf person, any insane person at large is allowed to drive.”

The original bill requiring a driver’s license in Idaho, as proposed in 1935, prohibited those who were deaf from driving. The Idaho Association for the Deaf pointed out that many of its members had been driving safely for years. That prohibition was removed.

Meanwhile, the Idaho Statesman had switched sides in the intervening decades. The paper published at least three editorials opposing the bill on the grounds that it was just another way for the state government to take 50 cents or a dollar out of taxpayers’ pockets. “The administration of the act would only mean the establishment of one more bureau to add to the countless others in the state house, more inspectors, more clerks, more examiners to support from the general fund. As a matter of fact, one cannot be blamed for suspecting that this is the reason why many of the politicians like the proposed law.”

Some of those politicians felt the same way. On February 16, 1935, the Statesman reported on debate on S.B. 1, the driver’s license bill. “Senator Clark, Bonneville, tore into the bill with a whirlwind attack in which he said the measure was just one more of the encroachments of bureaucracy on the rights of the common people, just taking a little nick out of the family purse here and there.”

Senator Wilson, of Gem County called the bill “nothing but a tax and a few white collar jobs.” He added, “Pretty soon they’ll be taxing baldheaded men, or foolish men, and then won’t I feel sick?”

The bill’s sponsor, Senator Yost from Ada County accused his fellow lawmakers “of shedding crocodile tears for the fate of the poor fellows who would pay 50 cents each but ignoring the fate of the 124 who filled fresh graves in Idaho in 1934 because of automobile deaths.” There were 200,000 drivers that year in the state.

Senator James Just of Bingham County was not quoted. I bring him up only because my grandfather was a notoriously awful driver, yet he voted for the measure. It passed the senate by one vote. The Statesman ran two more editorials after the fact grousing about the bill.

So, finally, Idaho had a driver’s license law. It was just a matter of filling out a form and finding a couple of quarters to pay for the license. The state didn’t begin requiring a test for drivers until 1951.

As long as it took Idaho to get licensing into law, it was by no means the last state to do so. South Dakota didn’t require its drivers to hold a license until 1954.

The first mention of a driver’s license for Idahoans that I could find was in an Idaho Statesman editorial on July 8, 1911. The paper was proposing a city driver’s license ordinance after the death of a young girl on the streets. She was killed by a streetcar. The Statesman called for licensing streetcar operators and operators of automobiles, as well.

Boise was behind at least one other Idaho city when it came to licensing. Those driving automobiles in Twin Falls in 1912 were reminded in the Twin Falls Times that they must take out a license to drive. It would cost them $1.

In 1917 the City of Boise passed an ordinance requiring livery drivers to purchase a license. The city council revoked at least a couple of licenses that year, one for drunk driving.

1924 was the first year a bill to require drivers to be licensed came up in the Idaho Legislature. One Statesman headline touted the “Examination of Drivers to Eliminate all Evils.” Requiring drivers to obtain a license was seen as a safety measure, not because they had to take a test, but because the state would then have the ability to take away a license from a driver who proved to be reckless. The bill went nowhere.

In 1927, the idea was back in the Idaho Legislature. National organizations were pushing for universal automobile legislation state by state. Idaho legislators then were about as ready to accept anything that smelled like federal government meddling as they are now. Nada on the driver’s license bill.

By 1928 there were 12 states requiring driver’s licenses. Only five of them required a test to obtain a license. That year the Idaho Statesman ran an article from a national motor club pointing out that “in all too many states, any boy or girl, any deaf person, any insane person at large is allowed to drive.”

The original bill requiring a driver’s license in Idaho, as proposed in 1935, prohibited those who were deaf from driving. The Idaho Association for the Deaf pointed out that many of its members had been driving safely for years. That prohibition was removed.

Meanwhile, the Idaho Statesman had switched sides in the intervening decades. The paper published at least three editorials opposing the bill on the grounds that it was just another way for the state government to take 50 cents or a dollar out of taxpayers’ pockets. “The administration of the act would only mean the establishment of one more bureau to add to the countless others in the state house, more inspectors, more clerks, more examiners to support from the general fund. As a matter of fact, one cannot be blamed for suspecting that this is the reason why many of the politicians like the proposed law.”

Some of those politicians felt the same way. On February 16, 1935, the Statesman reported on debate on S.B. 1, the driver’s license bill. “Senator Clark, Bonneville, tore into the bill with a whirlwind attack in which he said the measure was just one more of the encroachments of bureaucracy on the rights of the common people, just taking a little nick out of the family purse here and there.”

Senator Wilson, of Gem County called the bill “nothing but a tax and a few white collar jobs.” He added, “Pretty soon they’ll be taxing baldheaded men, or foolish men, and then won’t I feel sick?”

The bill’s sponsor, Senator Yost from Ada County accused his fellow lawmakers “of shedding crocodile tears for the fate of the poor fellows who would pay 50 cents each but ignoring the fate of the 124 who filled fresh graves in Idaho in 1934 because of automobile deaths.” There were 200,000 drivers that year in the state.

Senator James Just of Bingham County was not quoted. I bring him up only because my grandfather was a notoriously awful driver, yet he voted for the measure. It passed the senate by one vote. The Statesman ran two more editorials after the fact grousing about the bill.

So, finally, Idaho had a driver’s license law. It was just a matter of filling out a form and finding a couple of quarters to pay for the license. The state didn’t begin requiring a test for drivers until 1951.

As long as it took Idaho to get licensing into law, it was by no means the last state to do so. South Dakota didn’t require its drivers to hold a license until 1954.

Published on September 28, 2019 04:00