Rick Just's Blog, page 179

November 26, 2019

Chief Washakie

Chief Washakie. Library of Congress photo. Back before there was an Idaho, or a Wyoming, or pick your state, there was a Shoshoni land that stretched irregularly from Death Valley north to where Salmon is today, and east into the Wind River Range. It encompassed much of southern Idaho and northern Utah.

Chief Washakie. Library of Congress photo. Back before there was an Idaho, or a Wyoming, or pick your state, there was a Shoshoni land that stretched irregularly from Death Valley north to where Salmon is today, and east into the Wind River Range. It encompassed much of southern Idaho and northern Utah.It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

Published on November 26, 2019 04:00

November 25, 2019

"Upside Down Pang"

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

In about 1919, St. Maries, that north Idaho logging town on the banks of the Shadowy St. Joe, was the site of a portentous meeting between famous aviators. Neither had yet risen to fame, but Edward Pangborn was well on his way.

Pangborn, who grew up in St. Maries and took civil engineering courses at the University of Idaho for a couple of years, learned to fly during World War I, becoming a flight instructor at Ellington Field in Houston. He gained a reputation there for stunt flying, earning the nickname “Upside Down Pang.”

It was stunt flying—barnstorming—that brought him back to St. Maries following the war. He was a pilot for Gates Flying Circus, and a partner in the operation. As barnstorming pilots often did, Pangborn offered short flights to local citizens. Little Gregory Boyington got his first ride in an airplane that day. He would later become famous as Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, a Medal of Honor winner, during World War II.

Pangborn’s fame grew during his nine years as a barnstormer. He was known particularly for changing planes in mid-air, walking out on the wing of one plane and slipping over to the wing of another flying wingtip to wingtip.

In 1931, Pangborn and co-pilot Hugh Herndon sought to break the record for circumnavigating the globe. Nasty weather over Siberia caused them to abandon their efforts. So, they set their sights on another record. The two flew to Japan where they hoped to win a $25,000 prize for being the first to complete a non-stop trans-Pacific flight.

Their attempt was plagued with problems. First, they were arrested for taking pictures while flying over Japanese naval installations. Paying a $1,000 fine got them released, but the Japanese kicked them out of the country. They could take off, but they would be arrested again if they tried to land in Japan because they didn’t have proper documentation.

One chance was all they needed. They filled their plane, a Bellanca CH-400 (photo) called Miss Veedol, with over 900 gallons of fuel, and took off on October 4, 1931. The term “flying by the seat of their pants” may not have been invented to describe this flight, but that is largely what they had to do. Their maps and charts had been stolen by a group who wanted a Japanese pilot to be the first to cross the Pacific non-stop.

Part of the plan to get across the ocean with limited fuel was to drop the landing gear from the plane so there would be less drag. The wheels fell away when the lever inside the cockpit was pulled, but a pair of struts stubbornly remained in place. Those caused unwanted drag, which would use precious fuel and make a belly landing—their plan—dangerous. Harkening back to his wing-walking days, Pangborn slipped out of the cockpit at 14,000 feet, barefoot, and removed the struts manually.

Everything went swimmingly from then on except for their inability to land and that time when the engine quit because the co-pilot had neglected to transfer fuel from the auxiliary tanks to the main on time. The plane, stripped of everything not absolutely necessary, didn’t have a starter. The plane also lacked survival gear, seat cushions, and a radio. Pangborn put the Bellanca into a nosedive to get the prop spinning fast enough to start the plane. We know that worked because I did not just write “and then they died.”

Weather was again their enemy, as it had been over Siberia during the global attempt. They planned to land in Seattle or Vancouver, B.C., but both airfields were socked in. So was Mt. Rainier, which they came close to kissing. So, on to Boise! But no, fog had Boise, Spokane, and Pasco closed.

All they wanted to do, badly, was land. And, eventually, they did. Badly, one could say. Of course, given that the plane had no landing gear any landing one could walk away from was perfect. Pangborn and Herndon belly-landed in the dirt field at Wenatchee, 41 hours and 13 minutes after taking off from Japan, officially becoming the first to fly non-stop across the Pacific.

Trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic flights would become routine for Pangborn, who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939. He made 170 trans-oceanic flights in helping to recruit American pilots to the cause. When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, he signed up with the U.S. Army Air Force.

Pangborn passed away in 1958 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

In about 1919, St. Maries, that north Idaho logging town on the banks of the Shadowy St. Joe, was the site of a portentous meeting between famous aviators. Neither had yet risen to fame, but Edward Pangborn was well on his way.

Pangborn, who grew up in St. Maries and took civil engineering courses at the University of Idaho for a couple of years, learned to fly during World War I, becoming a flight instructor at Ellington Field in Houston. He gained a reputation there for stunt flying, earning the nickname “Upside Down Pang.”

It was stunt flying—barnstorming—that brought him back to St. Maries following the war. He was a pilot for Gates Flying Circus, and a partner in the operation. As barnstorming pilots often did, Pangborn offered short flights to local citizens. Little Gregory Boyington got his first ride in an airplane that day. He would later become famous as Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, a Medal of Honor winner, during World War II.

Pangborn’s fame grew during his nine years as a barnstormer. He was known particularly for changing planes in mid-air, walking out on the wing of one plane and slipping over to the wing of another flying wingtip to wingtip.

In 1931, Pangborn and co-pilot Hugh Herndon sought to break the record for circumnavigating the globe. Nasty weather over Siberia caused them to abandon their efforts. So, they set their sights on another record. The two flew to Japan where they hoped to win a $25,000 prize for being the first to complete a non-stop trans-Pacific flight.

Their attempt was plagued with problems. First, they were arrested for taking pictures while flying over Japanese naval installations. Paying a $1,000 fine got them released, but the Japanese kicked them out of the country. They could take off, but they would be arrested again if they tried to land in Japan because they didn’t have proper documentation.

One chance was all they needed. They filled their plane, a Bellanca CH-400 (photo) called Miss Veedol, with over 900 gallons of fuel, and took off on October 4, 1931. The term “flying by the seat of their pants” may not have been invented to describe this flight, but that is largely what they had to do. Their maps and charts had been stolen by a group who wanted a Japanese pilot to be the first to cross the Pacific non-stop.

Part of the plan to get across the ocean with limited fuel was to drop the landing gear from the plane so there would be less drag. The wheels fell away when the lever inside the cockpit was pulled, but a pair of struts stubbornly remained in place. Those caused unwanted drag, which would use precious fuel and make a belly landing—their plan—dangerous. Harkening back to his wing-walking days, Pangborn slipped out of the cockpit at 14,000 feet, barefoot, and removed the struts manually.

Everything went swimmingly from then on except for their inability to land and that time when the engine quit because the co-pilot had neglected to transfer fuel from the auxiliary tanks to the main on time. The plane, stripped of everything not absolutely necessary, didn’t have a starter. The plane also lacked survival gear, seat cushions, and a radio. Pangborn put the Bellanca into a nosedive to get the prop spinning fast enough to start the plane. We know that worked because I did not just write “and then they died.”

Weather was again their enemy, as it had been over Siberia during the global attempt. They planned to land in Seattle or Vancouver, B.C., but both airfields were socked in. So was Mt. Rainier, which they came close to kissing. So, on to Boise! But no, fog had Boise, Spokane, and Pasco closed.

All they wanted to do, badly, was land. And, eventually, they did. Badly, one could say. Of course, given that the plane had no landing gear any landing one could walk away from was perfect. Pangborn and Herndon belly-landed in the dirt field at Wenatchee, 41 hours and 13 minutes after taking off from Japan, officially becoming the first to fly non-stop across the Pacific.

Trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic flights would become routine for Pangborn, who joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939. He made 170 trans-oceanic flights in helping to recruit American pilots to the cause. When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, he signed up with the U.S. Army Air Force.

Pangborn passed away in 1958 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Published on November 25, 2019 04:00

November 24, 2019

Pulling Hill

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

The Google Earth satellite photo of Pulling Hill on the northeast side of the Presto Bench a few miles outside of Firth looks a little like an art installation. Motorcycles installed it, for the most part. I helped with that as a kid. In the winter the hillsides were where everyone went to sleigh and sometimes snowmobile.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

The Google Earth satellite photo of Pulling Hill on the northeast side of the Presto Bench a few miles outside of Firth looks a little like an art installation. Motorcycles installed it, for the most part. I helped with that as a kid. In the winter the hillsides were where everyone went to sleigh and sometimes snowmobile.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Published on November 24, 2019 04:00

November 23, 2019

An Aviator Hero

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Gregory Hallenbeck was born in Coeur d’Alene in 1912, but at age three he moved with his family to the logging town of St. Maries. It was there, at age 6, that Gregory had his first airplane ride with barnstormer Clyde Pangborn. He would cruise the clouds many times after that.

The Hallenbeck family moved to Tacoma when he was twelve. Gregory attended the University of Washington, graduating in 1934 with a BS in aeronautical engineering. He married and went to work for Boeing as an engineer and draftsman.

Gregory wanted to fly, not just work on airplane design. In 1935 he applied for a slot with the Navy as an aviation cadet. They rejected him because he was married. He wasn’t going to get a divorce, so that path into the air seemed closed. That is, until he got a copy of his birth certificate and learned that Ellsworth Hallenback, his father, was not really his father. Gregory’s father was a dentist by the name of Charles Boyington. Boyington and Gregory’s mother had divorced when Gregory was a baby.

Finding out your personal history was not what you thought it was might have been traumatic for the young man, but Gregory changed his name to his birth name and reapplied to the Navy program. Under that new/old name he didn’t bother to mention that he was married. They accepted him as an aviation cadet.

In 1937, Gregory Boyington became second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Then in 1941, Boyington took what might have seemed to be a detour. He resigned his commission in the Marine Corps and went to work for the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company. The company was real, but the job was a ruse. American entrepreneur William Pawley ran the company in China. In 1941 he began recruiting American pilots for his American Volunteer Group, also known as the Flying Tigers. President Franklin Roosevelt had authorized the covert operation where the US pilots would fly airplanes marked with the colors of China, fighting the Japanese. Ironically, they didn’t see their first action until 12 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Boyington was credited with the destruction of three Japanese aircraft during his brief stint with the Flying Tigers, two in the air and one on the ground. In September of 1942 he rejoined the Marine Corps where his story would become legendary. A year later he would become the commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 214, nicknamed the Black Sheep Squadron.

It was while he was with the Black Sheep that he earned a nickname. They called him “Gramps” because at 31 was years older than most of the pilots. That morphed into “Pappy,” giving him the moniker that would stay with him in the history books, Gregory “Pappy” Boyington,

During his first tour “Pappy” took down 14 enemy fighters in 32 days. He shared the bravura and a bit of the PR man with Pangborn, the barnstormer who first took him into the skies. Boyington and his men would buzz enemy airfields luring fighters into the sky where they could be picked off. The PR man appeared when he boasted that he and his squadron would shoot down a Japanese Zero for every cap the ball players in the World Series would send them. They got 20 hats. The Japanese lost 20 aircraft, and then some.

But his luck didn’t hold. In January, 1944, Boyington was shot down over the Pacific just after making his own 26th kill. He was presumed dead, but he had actually been plucked out of the water by a Japanese submarine. For nearly two years Boyington was a POW, freed finally when American forces liberated the Omori Prison Camp.

For his wartime heroics Gregory “Pappy” Boyington received the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. His 1958 autobiography, Baa Baa Black Sheep was used as the basis for the TV series that ran for a couple of years in the 70s.

Boyington, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer in 1988 at age 75.

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington. Library of Congress photo.

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington. Library of Congress photo.

Gregory Hallenbeck was born in Coeur d’Alene in 1912, but at age three he moved with his family to the logging town of St. Maries. It was there, at age 6, that Gregory had his first airplane ride with barnstormer Clyde Pangborn. He would cruise the clouds many times after that.

The Hallenbeck family moved to Tacoma when he was twelve. Gregory attended the University of Washington, graduating in 1934 with a BS in aeronautical engineering. He married and went to work for Boeing as an engineer and draftsman.

Gregory wanted to fly, not just work on airplane design. In 1935 he applied for a slot with the Navy as an aviation cadet. They rejected him because he was married. He wasn’t going to get a divorce, so that path into the air seemed closed. That is, until he got a copy of his birth certificate and learned that Ellsworth Hallenback, his father, was not really his father. Gregory’s father was a dentist by the name of Charles Boyington. Boyington and Gregory’s mother had divorced when Gregory was a baby.

Finding out your personal history was not what you thought it was might have been traumatic for the young man, but Gregory changed his name to his birth name and reapplied to the Navy program. Under that new/old name he didn’t bother to mention that he was married. They accepted him as an aviation cadet.

In 1937, Gregory Boyington became second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. Then in 1941, Boyington took what might have seemed to be a detour. He resigned his commission in the Marine Corps and went to work for the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company. The company was real, but the job was a ruse. American entrepreneur William Pawley ran the company in China. In 1941 he began recruiting American pilots for his American Volunteer Group, also known as the Flying Tigers. President Franklin Roosevelt had authorized the covert operation where the US pilots would fly airplanes marked with the colors of China, fighting the Japanese. Ironically, they didn’t see their first action until 12 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Boyington was credited with the destruction of three Japanese aircraft during his brief stint with the Flying Tigers, two in the air and one on the ground. In September of 1942 he rejoined the Marine Corps where his story would become legendary. A year later he would become the commanding officer of Marine Fighter Squadron 214, nicknamed the Black Sheep Squadron.

It was while he was with the Black Sheep that he earned a nickname. They called him “Gramps” because at 31 was years older than most of the pilots. That morphed into “Pappy,” giving him the moniker that would stay with him in the history books, Gregory “Pappy” Boyington,

During his first tour “Pappy” took down 14 enemy fighters in 32 days. He shared the bravura and a bit of the PR man with Pangborn, the barnstormer who first took him into the skies. Boyington and his men would buzz enemy airfields luring fighters into the sky where they could be picked off. The PR man appeared when he boasted that he and his squadron would shoot down a Japanese Zero for every cap the ball players in the World Series would send them. They got 20 hats. The Japanese lost 20 aircraft, and then some.

But his luck didn’t hold. In January, 1944, Boyington was shot down over the Pacific just after making his own 26th kill. He was presumed dead, but he had actually been plucked out of the water by a Japanese submarine. For nearly two years Boyington was a POW, freed finally when American forces liberated the Omori Prison Camp.

For his wartime heroics Gregory “Pappy” Boyington received the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. His 1958 autobiography, Baa Baa Black Sheep was used as the basis for the TV series that ran for a couple of years in the 70s.

Boyington, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer in 1988 at age 75.

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington. Library of Congress photo.

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington. Library of Congress photo.

Published on November 23, 2019 04:00

November 22, 2019

(Large Body of Water) Cascade

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Sometimes place names are a little deceptive, and deliberately so.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

Published on November 22, 2019 04:00

November 21, 2019

Speaking of... Trumpets

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Things can get noisy when a fire is raging. That’s why the foreman of the Ada Hook and Ladder Company would use a “speaking trumpet” when they were called out on a fire. Speaking Trumpets were essentially brass megaphones. They sometimes served a second purpose, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. They could be inscribed and awarded to honor firefighters for their service.

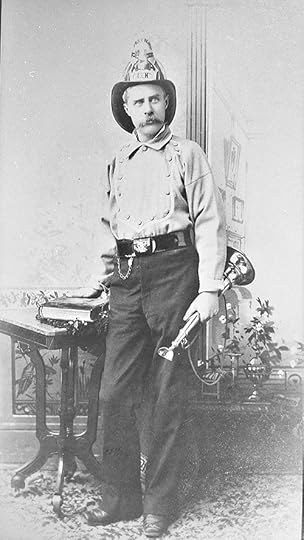

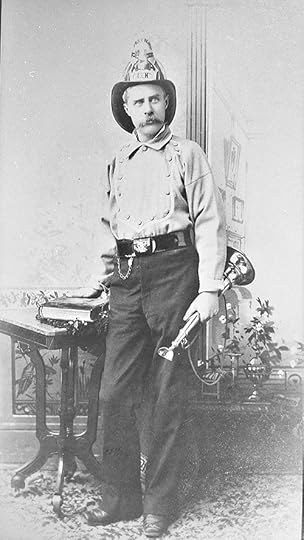

The fire foreman holding the speaking trumpet in this photo is James "Jimmy" H. Hart. It was probably taken around 1900.

Hart was born in in New York City in 1834. He came west to earn his fortune in the gold fields and found that serving liquor to miners was a better way to get gold than digging for it. According to Hugh Hartman’s book, The Founding Fathers of Boise, Hart started Jim’s Drinking Saloon in Placerville in 1863 with $9.75. That first year he grossed $30,000 and netted $12,000. His business acumen may have been what got him elected city treasurer.

According to Hartman’s book, Jim Hart had a special way of building up the town treasury. He was quoted as saying, “We had a plaza in the center of the town, on which was a flag pole. I’d play a trick on some good marksman by hinting that he couldn’t hit the pole with his gun. In the meantime, I’d have the Sheriff stationed ready to make the arrest as soon as the man shot. Then the judge would fine him ten dollars, and to get even he’d play the trick on someone else. Then when we had about fifty dollars in the treasury, we would blow it on champagne.”

Hart and his family moved to Boise in 1871 where he was a saloon keeper, a city tax assessor, the proprietor of Jimmy Hart’s Grocery and Bakery Sample Room, and a volunteer firefighter, which is something to trumpet about. James Hart with speaking trumpet. Photo Courtesy of Hugh Hartman.

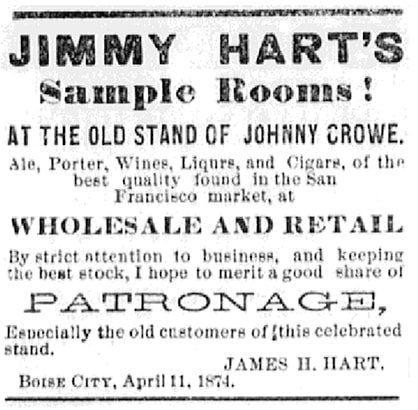

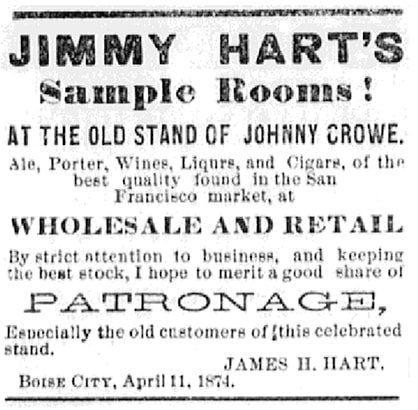

James Hart with speaking trumpet. Photo Courtesy of Hugh Hartman.  An ad from Jimmy Hart's drinking establishment.

An ad from Jimmy Hart's drinking establishment.

Things can get noisy when a fire is raging. That’s why the foreman of the Ada Hook and Ladder Company would use a “speaking trumpet” when they were called out on a fire. Speaking Trumpets were essentially brass megaphones. They sometimes served a second purpose, according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. They could be inscribed and awarded to honor firefighters for their service.

The fire foreman holding the speaking trumpet in this photo is James "Jimmy" H. Hart. It was probably taken around 1900.

Hart was born in in New York City in 1834. He came west to earn his fortune in the gold fields and found that serving liquor to miners was a better way to get gold than digging for it. According to Hugh Hartman’s book, The Founding Fathers of Boise, Hart started Jim’s Drinking Saloon in Placerville in 1863 with $9.75. That first year he grossed $30,000 and netted $12,000. His business acumen may have been what got him elected city treasurer.

According to Hartman’s book, Jim Hart had a special way of building up the town treasury. He was quoted as saying, “We had a plaza in the center of the town, on which was a flag pole. I’d play a trick on some good marksman by hinting that he couldn’t hit the pole with his gun. In the meantime, I’d have the Sheriff stationed ready to make the arrest as soon as the man shot. Then the judge would fine him ten dollars, and to get even he’d play the trick on someone else. Then when we had about fifty dollars in the treasury, we would blow it on champagne.”

Hart and his family moved to Boise in 1871 where he was a saloon keeper, a city tax assessor, the proprietor of Jimmy Hart’s Grocery and Bakery Sample Room, and a volunteer firefighter, which is something to trumpet about.

James Hart with speaking trumpet. Photo Courtesy of Hugh Hartman.

James Hart with speaking trumpet. Photo Courtesy of Hugh Hartman.  An ad from Jimmy Hart's drinking establishment.

An ad from Jimmy Hart's drinking establishment.

Published on November 21, 2019 04:00

November 20, 2019

Iowa Boy Makes Good

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

J.R. Simplot was not born in Idaho. He was born in—wait for it—Iowa, thus further confusing those who can’t tell the two states apart.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

J.R. Simplot was not born in Idaho. He was born in—wait for it—Iowa, thus further confusing those who can’t tell the two states apart.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Published on November 20, 2019 04:00

November 19, 2019

The Boise Shoshoni

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Boise was known for its trees long before it was a city, or even a town. The first people who lived where what is now the City of Trees is located, the Northern Shoshoni, called it Subu Wiki, meaning something like “willows in many rows.” The Nez Perce, who knew it as a home of the Shoshoni called it Cup cop pa ala, or “the much feast cottonwood valley,” probably in recognition of the rendezvous many bands held along the Boise River. Hudson’s Bay trapper Donald McKenzie witnessed one of those rendezvous in 1819 and reported the crowd gathered to be “more than 10,000 souls” camped along the river between Table Rock and Eagle Island.

We recognize Boise as a good place to live today for many of the same reasons the indigenous people did. It has mild winters and mostly moderate summers. There are hot springs to keep sweat lodges steaming or the capitol heated. The river provides a good fishery.

In those days, the Boise River provided an outstanding fishery that was essential to the subsistence of the Shoshoni. When the first white settlers came into the valley, they wrote of raking salmon out of the river with forked willow branches the fish were so plentiful.

Prior to pioneer settlement the Shoshoni hunted bison on the Snake River Plain, especially after 1700 when they acquired horses, the first Northwest Tribe to do so.

Compare this life of plenty the Northern Shoshoni led with their miserable last few years in the Boise Valley.

In 1864 the Boise Shoshoni signed a treaty with Idaho Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, whom it is always pointed out hailed from Lyonsdale, New York, largely because he never failed to mention it. The treaty gave the natives a never-defined amount of money and a not described place to live in the indistinct future in exchange for their homeland of hundreds of years. Though their land was gobbled up, the exchange went only that far. Lyon disappeared along with $50,000 meant for the Indians. Lyon insisted thieves had stolen the money from him while he was en route to Washington, D.C. Why he had the money with him in the first place was never explained. Possibly for safe keeping.

What followed, for the Shoshoni, were several years of waiting on the outskirts of Boise for the promises of the treaty to be kept. It was never ratified by the U.S. Senate, though that would probably not have made much difference.

This encampment of Indians is seldom mentioned in Boise history. Carol Lynn MacGregor brought it to light in her excellent book, Boise, Idaho, 1882-1910 from which much of the information for this post was taken.

Over 1,000 Shoshoni and 150 Bannock awaited promises just outside of town. They did what they could to make a living, fishing and hunting as they always had, but with much reduced opportunity. Some took odd jobs in town to earn money for food. Disease in the Shoshoni camp was rampant, with many of the natives suffering from measles and consumption (tuberculosis).

Finally, in 1869, after five years of being homeless in their traditional homeland, the Indians were moved to the reservation at Fort Hall. Today, few but the willows and cottonwoods remember the people who first gave a name to the valley.

Castle Rock, near the old Idaho Penitentiary, held special significance to the Boise Shoshoni.

Castle Rock, near the old Idaho Penitentiary, held special significance to the Boise Shoshoni.

Boise was known for its trees long before it was a city, or even a town. The first people who lived where what is now the City of Trees is located, the Northern Shoshoni, called it Subu Wiki, meaning something like “willows in many rows.” The Nez Perce, who knew it as a home of the Shoshoni called it Cup cop pa ala, or “the much feast cottonwood valley,” probably in recognition of the rendezvous many bands held along the Boise River. Hudson’s Bay trapper Donald McKenzie witnessed one of those rendezvous in 1819 and reported the crowd gathered to be “more than 10,000 souls” camped along the river between Table Rock and Eagle Island.

We recognize Boise as a good place to live today for many of the same reasons the indigenous people did. It has mild winters and mostly moderate summers. There are hot springs to keep sweat lodges steaming or the capitol heated. The river provides a good fishery.

In those days, the Boise River provided an outstanding fishery that was essential to the subsistence of the Shoshoni. When the first white settlers came into the valley, they wrote of raking salmon out of the river with forked willow branches the fish were so plentiful.

Prior to pioneer settlement the Shoshoni hunted bison on the Snake River Plain, especially after 1700 when they acquired horses, the first Northwest Tribe to do so.

Compare this life of plenty the Northern Shoshoni led with their miserable last few years in the Boise Valley.

In 1864 the Boise Shoshoni signed a treaty with Idaho Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, whom it is always pointed out hailed from Lyonsdale, New York, largely because he never failed to mention it. The treaty gave the natives a never-defined amount of money and a not described place to live in the indistinct future in exchange for their homeland of hundreds of years. Though their land was gobbled up, the exchange went only that far. Lyon disappeared along with $50,000 meant for the Indians. Lyon insisted thieves had stolen the money from him while he was en route to Washington, D.C. Why he had the money with him in the first place was never explained. Possibly for safe keeping.

What followed, for the Shoshoni, were several years of waiting on the outskirts of Boise for the promises of the treaty to be kept. It was never ratified by the U.S. Senate, though that would probably not have made much difference.

This encampment of Indians is seldom mentioned in Boise history. Carol Lynn MacGregor brought it to light in her excellent book, Boise, Idaho, 1882-1910 from which much of the information for this post was taken.

Over 1,000 Shoshoni and 150 Bannock awaited promises just outside of town. They did what they could to make a living, fishing and hunting as they always had, but with much reduced opportunity. Some took odd jobs in town to earn money for food. Disease in the Shoshoni camp was rampant, with many of the natives suffering from measles and consumption (tuberculosis).

Finally, in 1869, after five years of being homeless in their traditional homeland, the Indians were moved to the reservation at Fort Hall. Today, few but the willows and cottonwoods remember the people who first gave a name to the valley.

Castle Rock, near the old Idaho Penitentiary, held special significance to the Boise Shoshoni.

Castle Rock, near the old Idaho Penitentiary, held special significance to the Boise Shoshoni.

Published on November 19, 2019 04:00

November 18, 2019

A Legendary Packer

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

When you were a miner in the early days of Idaho, you couldn’t just order up supplies from Amazon. There were no planes, no trucks, and most importantly, no roads. Everything had to be packed in to remote areas, usually by a string of mules. If you had a big job, you counted on Jesus Urquides to get what you needed where you needed it.

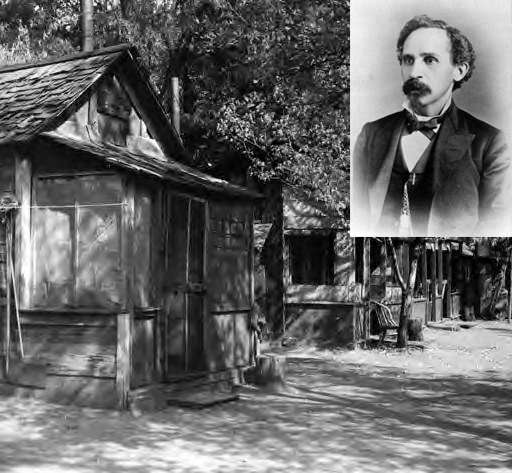

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

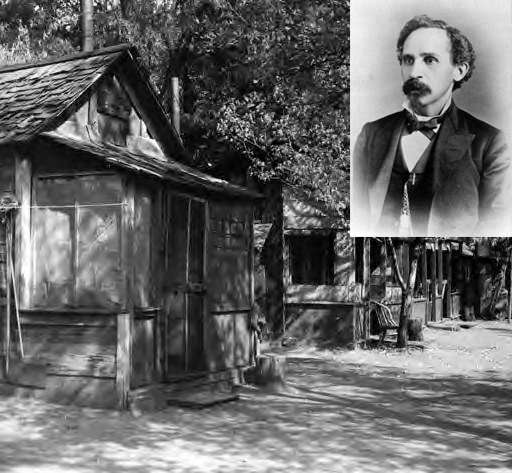

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

When you were a miner in the early days of Idaho, you couldn’t just order up supplies from Amazon. There were no planes, no trucks, and most importantly, no roads. Everything had to be packed in to remote areas, usually by a string of mules. If you had a big job, you counted on Jesus Urquides to get what you needed where you needed it.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of copper wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on November 18, 2019 04:00

November 17, 2019

A Boise Dentist and Entrepreneur

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

While skimming through the Hugh Hartman’s massive photo collection I found the picture below of an early Boise dentist. It was intriguing, so I decided to do a little digging on the dentist, Dr. Abraham Friedline.

One of the first things I found was that the doctor did a little digging himself. In addition to his dental duties he was the president of the X-Ray Mine, eight miles from Boise in the Black Hornet mining district near the town of Pearl. In his vision the X-Ray would be a mile-and-a-half tunnel through veins of quartz that would make him fabulously wealthy. Others could buy into the mine for 25 cents a share in 1903. The Statesman reported on progress in the mine for a couple of years, and on the trial of a man who had shot the mine manager to death while the manager was walking to work. The stories petered out, much as the gold in the mines near Pearl did after a few years.

But there was more than mining to Dr. Friedline. He was also a local real estate developer. The Statesman reported in 1902 that he was building “a handsome row of houses” on the northeast corner of 14th and State in Boise. The eight houses were to be two stories in height, each having six rooms, with closets, pantry, storeroom, baths, etc. Each pair of houses, built with adjoining walls, would have neat porticos over their entrance. The whole block would be made of brick and stone.

What would be first known as Friedline Terraces, would soon become called Friedline Flats. Those buildings are still in use today as apartments, the western side of which are across from the Fanci Freeze drive in.

It was his dental practice that drew me into the story. The photo below shows just how popular busy wallpaper was at the time, not to mention hardworking flooring and a ceiling that was positively hectic. Overlooking it all as if he had accidentally rammed his head through the wall and stayed there, stunned to stone by the decor, was an eight-point buck with a bandana tied around his neck. He may have been there as a reminder to patients under the drill at Denver Dental that things could be worse.

Dr. Friedline passed away in 1914 at the age of 66. His two sons, who had also become dentists, took over the practice.

Mrs. Friedline, a lovely woman, held a special place in her father’s heart. He was sure she would be a pal to him, so he named her that. Apal. Hugh Hartman, who generously supplied the photos for this story, was a friend of hers in later years. He remembers that when Apal was in her eighties she suddenly got a hankering for world travel. She asked him if he would take care of selling a 63-piece sterling silver service so she could take a spin around the globe. Hugh talked the manager of the Mode into putting the set in the popular department store’s display window, and soon Apal Friedline was seeing the sites she’d always dreamed of seeing. By all accounts, the deer stayed in Boise.

Dr. Abraham Friedline poses next to his patient chair at the Denver Dental office circa 1910.

Dr. Abraham Friedline poses next to his patient chair at the Denver Dental office circa 1910.  Dr. Friedline and his wife Apal in their home, which was on the corner of Washington and 14th, not far from Denver Dental.

Dr. Friedline and his wife Apal in their home, which was on the corner of Washington and 14th, not far from Denver Dental.  A contemporary photo of Friedline Flats on State Street at 14th.

A contemporary photo of Friedline Flats on State Street at 14th.

While skimming through the Hugh Hartman’s massive photo collection I found the picture below of an early Boise dentist. It was intriguing, so I decided to do a little digging on the dentist, Dr. Abraham Friedline.

One of the first things I found was that the doctor did a little digging himself. In addition to his dental duties he was the president of the X-Ray Mine, eight miles from Boise in the Black Hornet mining district near the town of Pearl. In his vision the X-Ray would be a mile-and-a-half tunnel through veins of quartz that would make him fabulously wealthy. Others could buy into the mine for 25 cents a share in 1903. The Statesman reported on progress in the mine for a couple of years, and on the trial of a man who had shot the mine manager to death while the manager was walking to work. The stories petered out, much as the gold in the mines near Pearl did after a few years.

But there was more than mining to Dr. Friedline. He was also a local real estate developer. The Statesman reported in 1902 that he was building “a handsome row of houses” on the northeast corner of 14th and State in Boise. The eight houses were to be two stories in height, each having six rooms, with closets, pantry, storeroom, baths, etc. Each pair of houses, built with adjoining walls, would have neat porticos over their entrance. The whole block would be made of brick and stone.

What would be first known as Friedline Terraces, would soon become called Friedline Flats. Those buildings are still in use today as apartments, the western side of which are across from the Fanci Freeze drive in.

It was his dental practice that drew me into the story. The photo below shows just how popular busy wallpaper was at the time, not to mention hardworking flooring and a ceiling that was positively hectic. Overlooking it all as if he had accidentally rammed his head through the wall and stayed there, stunned to stone by the decor, was an eight-point buck with a bandana tied around his neck. He may have been there as a reminder to patients under the drill at Denver Dental that things could be worse.

Dr. Friedline passed away in 1914 at the age of 66. His two sons, who had also become dentists, took over the practice.

Mrs. Friedline, a lovely woman, held a special place in her father’s heart. He was sure she would be a pal to him, so he named her that. Apal. Hugh Hartman, who generously supplied the photos for this story, was a friend of hers in later years. He remembers that when Apal was in her eighties she suddenly got a hankering for world travel. She asked him if he would take care of selling a 63-piece sterling silver service so she could take a spin around the globe. Hugh talked the manager of the Mode into putting the set in the popular department store’s display window, and soon Apal Friedline was seeing the sites she’d always dreamed of seeing. By all accounts, the deer stayed in Boise.

Dr. Abraham Friedline poses next to his patient chair at the Denver Dental office circa 1910.

Dr. Abraham Friedline poses next to his patient chair at the Denver Dental office circa 1910.  Dr. Friedline and his wife Apal in their home, which was on the corner of Washington and 14th, not far from Denver Dental.

Dr. Friedline and his wife Apal in their home, which was on the corner of Washington and 14th, not far from Denver Dental.  A contemporary photo of Friedline Flats on State Street at 14th.

A contemporary photo of Friedline Flats on State Street at 14th.

Published on November 17, 2019 04:00