Rick Just's Blog, page 178

December 6, 2019

Goodbye to Steamboats

Steamboat. Does the word conjure up images of sternwheelers on the Mississippi? If you learned about steamers from Mark Twain, certainly it must. Yet Idaho has a rich steamboat history of its own.

Fort Coeur d'Alene was built on the north shore of Lake Coeur d'Alene in 1878, where the town is now. With that big, beautiful lake beckoning, it didn't take them long to build a boat. The sternwheeler Amelia Wheaton--named after the post commander's daughter--was launched on the lake in 1880. It was to be the first of many steamboats to ply the waters of Lake Coeur d'Alene.

Steamboats--sternwheelers, side-wheelers, and propeller drives--hauled ore, lumber, and supplies as work boats. Then, on holidays, many steamers became excursion boats, taking people from Spokane for picnics and outings across the lake and up the St. Joe River, or to Cataldo Mission, or Chatcolet.

For most of 50 years, steamboats were a basic part of life on Lake Coeur d'Alene. Then other forms of transportation--trains and automobiles--spelled their doom. Steamboats fell into disuse as the steamer companies fell into bankruptcy. Fire claimed most of them. Accidental fires took the North Star, the Boneta, the Seattle, the Harrison, and the Idaho. Others were scuttled and lie at the bottom of the lake. The grand lady of the lake, the Georgie Oakes--built in 1890--was set on fire for entertainment on the Fourth of July in 1927. The Georgie Oakes at Mission Landing on the Coeur d'Alene River.

The Georgie Oakes at Mission Landing on the Coeur d'Alene River.

Fort Coeur d'Alene was built on the north shore of Lake Coeur d'Alene in 1878, where the town is now. With that big, beautiful lake beckoning, it didn't take them long to build a boat. The sternwheeler Amelia Wheaton--named after the post commander's daughter--was launched on the lake in 1880. It was to be the first of many steamboats to ply the waters of Lake Coeur d'Alene.

Steamboats--sternwheelers, side-wheelers, and propeller drives--hauled ore, lumber, and supplies as work boats. Then, on holidays, many steamers became excursion boats, taking people from Spokane for picnics and outings across the lake and up the St. Joe River, or to Cataldo Mission, or Chatcolet.

For most of 50 years, steamboats were a basic part of life on Lake Coeur d'Alene. Then other forms of transportation--trains and automobiles--spelled their doom. Steamboats fell into disuse as the steamer companies fell into bankruptcy. Fire claimed most of them. Accidental fires took the North Star, the Boneta, the Seattle, the Harrison, and the Idaho. Others were scuttled and lie at the bottom of the lake. The grand lady of the lake, the Georgie Oakes--built in 1890--was set on fire for entertainment on the Fourth of July in 1927.

The Georgie Oakes at Mission Landing on the Coeur d'Alene River.

The Georgie Oakes at Mission Landing on the Coeur d'Alene River.

Published on December 06, 2019 04:00

December 5, 2019

Aurora Borah Alice

Our appetite for scandal seems not to diminish with history’s passing years. If you are above it, give yourself a gold star and quit reading now.

Okay, anyone still with me?

William Borah was a Boise attorney who went up against Clarence Darrow as one of the prosecutors of “Big” Bill Haywood. Haywood was acquitted but the trial brought national fame to Borah.

At the time of the trial in 1907, Borah had already been selected as a U.S. Senator from Idaho. That was when legislatures named senators. He had time for the trial because Congress didn’t start their sessions until December in those days. Borah replaced the vehemently anti-Mormon Fred T. Dubois. No scandal there, though no doubt there was some backroom intrigue, par for the course in elections on the floor.

No scandal, either, when Borah was reelected by the Legislature in 1912, or when he was elected and re-elected by the citizens in Idaho in 1918, 1924, 1930, and 1936.

Borah started showing up on presidential nomination ballots at Republican National Conventions beginning in 1916. He got the most votes in the Presidential Primaries in 1936, but Alf Landon won the nomination that year at the convention. Again, no scandal.

The scandal wasn’t on the political side for Borah, but on the personal side.

In 1895, Borah married the daughter of Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell. Mary McConnell was a lovely, tiny woman who during their years in Washington was often referred to as “Little Borah.” They had no children. And there’s the scandal. The senator apparently did.

Rumors of philandering dogged Senator Borah for years. Of particular interest for this particular scandal, was an affair he had with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt that was later confirmed by her diary entries.

Alice was married to Representative Nicholas Longworth III, who served as Speaker of the House. The daughter in question was ultimately named Paulina, but Alice, who had a wicked sense of humor, reportedly toyed with the idea of naming her Deborah. Deborah could have been read as De Borah, you see. According to H.W. Brands’ book A Traitor to His Class ,* which is largely about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Paulina was often referred to by D.C. wags as “Aurora Borah Alice.”

And, there you have it. Don’t say you weren’t warned. Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Alice Roosevelt Longworth in 1938. Library of Congress photo.

Alice Roosevelt Longworth in 1938. Library of Congress photo.

Okay, anyone still with me?

William Borah was a Boise attorney who went up against Clarence Darrow as one of the prosecutors of “Big” Bill Haywood. Haywood was acquitted but the trial brought national fame to Borah.

At the time of the trial in 1907, Borah had already been selected as a U.S. Senator from Idaho. That was when legislatures named senators. He had time for the trial because Congress didn’t start their sessions until December in those days. Borah replaced the vehemently anti-Mormon Fred T. Dubois. No scandal there, though no doubt there was some backroom intrigue, par for the course in elections on the floor.

No scandal, either, when Borah was reelected by the Legislature in 1912, or when he was elected and re-elected by the citizens in Idaho in 1918, 1924, 1930, and 1936.

Borah started showing up on presidential nomination ballots at Republican National Conventions beginning in 1916. He got the most votes in the Presidential Primaries in 1936, but Alf Landon won the nomination that year at the convention. Again, no scandal.

The scandal wasn’t on the political side for Borah, but on the personal side.

In 1895, Borah married the daughter of Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell. Mary McConnell was a lovely, tiny woman who during their years in Washington was often referred to as “Little Borah.” They had no children. And there’s the scandal. The senator apparently did.

Rumors of philandering dogged Senator Borah for years. Of particular interest for this particular scandal, was an affair he had with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt that was later confirmed by her diary entries.

Alice was married to Representative Nicholas Longworth III, who served as Speaker of the House. The daughter in question was ultimately named Paulina, but Alice, who had a wicked sense of humor, reportedly toyed with the idea of naming her Deborah. Deborah could have been read as De Borah, you see. According to H.W. Brands’ book A Traitor to His Class ,* which is largely about Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Paulina was often referred to by D.C. wags as “Aurora Borah Alice.”

And, there you have it. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo.

Mary McConnell Borah, circa 1909. Library of Congress photo. Alice Roosevelt Longworth in 1938. Library of Congress photo.

Alice Roosevelt Longworth in 1938. Library of Congress photo.

Published on December 05, 2019 04:00

December 4, 2019

Those Foot-Wide Towns

In the August 20, 1951 edition of Life Magazine there was an article entitled, “Idaho’s Foot-Wide Towns.” The article listed the towns of Banks, Garden City, Island Park, Batise, Chubbuck, Atomic City, and Island Park as examples of same. Crouch was the “foot-wide” town most prevalently featured, population 125, and 10 miles long.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

Published on December 04, 2019 04:00

December 3, 2019

Early Tragedy for an Idaho Author

Some writers are born from adversity. One of Idaho’s celebrated authors knew three notes of tragedy early in her life.

Carol Ryrie Brink’s birth was attended by her grandfather, Dr. William Woodbury Watkins. When the baby girl emerged, she did so silently. Her grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins, who was also there, whispered, “Stillborn.” Dr. Watkins had none of that. He picked up the infant and began breathing into its mouth. After a few moments the baby began to squirm and cry. As Brink said in her autobiography, A Chain of Hands, “He gave me my life more surely than my parents did.”

Her first tragedy was when her father, Alex Ryrie, died from tuberculosis when she was five. When Brink was six years old, she would know her second heartbreak. On August 4, 1901, her grandfather turned 55. It would be his last birthday.

On that Sunday, Dr. Watkins was driving a phaeton on his way to his office in Moscow where he was to attend to a sick young girl. As he approached an intersection a man on horseback rode up in front of Watkin’s carriage. Recognizing the man as William Steffans a local farmer and fellow Mason, he stopped and greeted him. Watkins knew Steffans as a violent man, one whom he had previously confronted after Steffans had beaten his own mother.

Steffans was not headed to church that day. He had a to-do list with him of the worst possible kind. The name of Dr. Watkins was on it. Steffans promptly pulled his pistol and shot the doctor. Watkins’ horse startled and ran, stopping only when it arrived at the familiar office of the man now sprawled dead on the seat of his carriage.

Meanwhile, Steffans rode through the streets of Moscow looking for people on his list that he had grudges with. He wasn’t having any luck finding them, so he began shooting randomly at anyone he saw, wounding several. The police were soon in pursuit. Foretelling the plot device of countless future movies, they shot not the tire of a criminal’s car, but the leg of his horse.

Afoot now, Steffans ran across the fields to his house and holed up inside. The townspeople formed a posse, gathered guns, and began a siege of the house. Steffans returned fire and the battle went on for some two hours. The mother he had treated so badly called out from inside the house that her son was dead. Whether from his own hand or a posse bullet is unclear.

In addition to Dr. Watkins a deputy died from wounds inflicted by Steffans.

Dr. Watkins was an engaged man, active not only in Moscow, but statewide. He was the first president of the state’s medical association, a member of the Board of Regents at the University of Idaho, and the chair of the first Idaho State Republican convention, during which he turned down a nomination for governor.

Brink honored her grandfather when she wrote a novel called Buffalo Coat in 1944. Based on his life, the book was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks.

The final early tragedy in Brink’s life was the suicide of her mother when Carol was nine following a disastrous marriage. After that the young girl went to live with her widowed grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins. It was her grandmother’s story, fictionalized in the book Caddie Woodlawn that won Brink the 1936 Newbery Medal for “distinguished contribution to American Literature for children.”

In all, Carol Ryrie Brink would write more than 30 books, including her acclaimed adult trilogy Buffalo Coat, Strangers in the Forest, and Snow on the River, the last of which won the National League of American Pen Women Fiction Award.

Carol Ryrie Brink passed away at age 85 in 1981.

Carol Ryrie Brink’s birth was attended by her grandfather, Dr. William Woodbury Watkins. When the baby girl emerged, she did so silently. Her grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins, who was also there, whispered, “Stillborn.” Dr. Watkins had none of that. He picked up the infant and began breathing into its mouth. After a few moments the baby began to squirm and cry. As Brink said in her autobiography, A Chain of Hands, “He gave me my life more surely than my parents did.”

Her first tragedy was when her father, Alex Ryrie, died from tuberculosis when she was five. When Brink was six years old, she would know her second heartbreak. On August 4, 1901, her grandfather turned 55. It would be his last birthday.

On that Sunday, Dr. Watkins was driving a phaeton on his way to his office in Moscow where he was to attend to a sick young girl. As he approached an intersection a man on horseback rode up in front of Watkin’s carriage. Recognizing the man as William Steffans a local farmer and fellow Mason, he stopped and greeted him. Watkins knew Steffans as a violent man, one whom he had previously confronted after Steffans had beaten his own mother.

Steffans was not headed to church that day. He had a to-do list with him of the worst possible kind. The name of Dr. Watkins was on it. Steffans promptly pulled his pistol and shot the doctor. Watkins’ horse startled and ran, stopping only when it arrived at the familiar office of the man now sprawled dead on the seat of his carriage.

Meanwhile, Steffans rode through the streets of Moscow looking for people on his list that he had grudges with. He wasn’t having any luck finding them, so he began shooting randomly at anyone he saw, wounding several. The police were soon in pursuit. Foretelling the plot device of countless future movies, they shot not the tire of a criminal’s car, but the leg of his horse.

Afoot now, Steffans ran across the fields to his house and holed up inside. The townspeople formed a posse, gathered guns, and began a siege of the house. Steffans returned fire and the battle went on for some two hours. The mother he had treated so badly called out from inside the house that her son was dead. Whether from his own hand or a posse bullet is unclear.

In addition to Dr. Watkins a deputy died from wounds inflicted by Steffans.

Dr. Watkins was an engaged man, active not only in Moscow, but statewide. He was the first president of the state’s medical association, a member of the Board of Regents at the University of Idaho, and the chair of the first Idaho State Republican convention, during which he turned down a nomination for governor.

Brink honored her grandfather when she wrote a novel called Buffalo Coat in 1944. Based on his life, the book was on the New York Times bestseller list for weeks.

The final early tragedy in Brink’s life was the suicide of her mother when Carol was nine following a disastrous marriage. After that the young girl went to live with her widowed grandmother, Carol Woodhouse Watkins. It was her grandmother’s story, fictionalized in the book Caddie Woodlawn that won Brink the 1936 Newbery Medal for “distinguished contribution to American Literature for children.”

In all, Carol Ryrie Brink would write more than 30 books, including her acclaimed adult trilogy Buffalo Coat, Strangers in the Forest, and Snow on the River, the last of which won the National League of American Pen Women Fiction Award.

Carol Ryrie Brink passed away at age 85 in 1981.

Published on December 03, 2019 04:00

December 2, 2019

Caribou Free Caribou County

There have been, occasionally, caribou in Idaho, and not just when Santa is flying over the state and, once again, pointedly skipping MY house. The caribou that until recently wandered in and out of Idaho in Boundary County, back and forth across the border with Canada, were the only caribou left in the Lower 48. The conservation effort that preserved them was abandoned and in early 2019 the last remaining caribou were removed to Canada.

Note that the caribou were in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website. Something you're unlikely to see browsing around Caribou County.

Something you're unlikely to see browsing around Caribou County.

Note that the caribou were in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Something you're unlikely to see browsing around Caribou County.

Something you're unlikely to see browsing around Caribou County.

Published on December 02, 2019 04:00

December 1, 2019

A Musical Interlude

And now, something completely different. It’s our first audio oriented post, thanks to Art Gregory of the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation.

If you were listening to radio in the 1960s in the Treasure Valley, you might remember the commercials from this short sample, featuring: Frosty Dog!Black Forrest Archery CenterYoung’s Dairy All Jersey MilkBank of IdahoIdaho First National BankWestern Idaho State Fair And, here’s the KIDO City of Trees jingle from 1961, featuring Gib Hochstrasser and Jeanie Hackett, cum Hochstrasser.

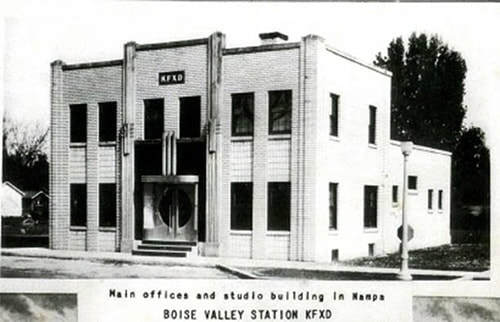

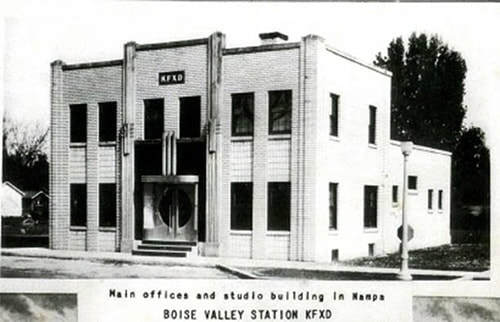

In 1962, KFXD had a song about the city where the station was located, which might have been called, Nampa-Nampa. Or, once you’ve heard it, you may think of something to call it yourself. Be kind. And finally, from 1978, KFXD’s I’ve Got a Song to Sing jingle, just a tad reminiscent of Coke jingles of the time. If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display (still looking for more), and they’re hoping to include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.

If you were listening to radio in the 1960s in the Treasure Valley, you might remember the commercials from this short sample, featuring: Frosty Dog!Black Forrest Archery CenterYoung’s Dairy All Jersey MilkBank of IdahoIdaho First National BankWestern Idaho State Fair And, here’s the KIDO City of Trees jingle from 1961, featuring Gib Hochstrasser and Jeanie Hackett, cum Hochstrasser.

In 1962, KFXD had a song about the city where the station was located, which might have been called, Nampa-Nampa. Or, once you’ve heard it, you may think of something to call it yourself. Be kind. And finally, from 1978, KFXD’s I’ve Got a Song to Sing jingle, just a tad reminiscent of Coke jingles of the time. If you like broadcasting history, consider giving a little money to the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation. They’re creating a museum in the old KFXD building in Nampa. They’ve got a ton of memorabilia to display (still looking for more), and they’re hoping to include recording studios. That’s the old KFXD building below. I looks much the same today.

Published on December 01, 2019 04:00

November 30, 2019

Pop Quiz!

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What is Sagehurst?

A. A ghost town near Leadore abandoned in 1897.

B. The ranch where Jackson Sundown grew up.

C. The name of the home built by Blackfoot Republican editor Byrd Trego.

D. One of several plants identified by the Corps of Discovery.

E. One of the highest producing mines in the Silver Valley.

2). Who was Pearl Tyre?

A. A Shoshoni scout for Col. Patrick Conner.

B. The proprietor of the Kitcheteria in Boise.

C. The proprietor of the Mechanicafe in Boise.

D. The proprietor of the old Chicken Inn in Nampa.

E. None of the above.

3). Why was a pioneer who died on the Oregon Trail dug up in 1909 and reburied in Twin Falls?

A. To move him closer to the graves of his family.

B. To provide the veteran a military funeral.

C. He was an Odd Fellow.

D. Because his grave marker was incorrect.

E. None of the above.

4). Who grew up as Gregory Hallenback?

A. The commander of the Black Sheep Squadron in WWII who won a Medal of Honor.

B. The last man hanged at the old Idaho State Prison.

C. Boxcar Willie.

D. Larry Lujack.

E. Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell.

5) What was Alfred Wilke known for?

A. He was the state checker champion of 1938.

B. He sold white leghorn chicks.

C. He manufactured and sold dog food in several states.

D. He sold singing canaries.

E. All of the above.

Answers

Answers

1, C

2, B

3, C

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture.

1). What is Sagehurst?

A. A ghost town near Leadore abandoned in 1897.

B. The ranch where Jackson Sundown grew up.

C. The name of the home built by Blackfoot Republican editor Byrd Trego.

D. One of several plants identified by the Corps of Discovery.

E. One of the highest producing mines in the Silver Valley.

2). Who was Pearl Tyre?

A. A Shoshoni scout for Col. Patrick Conner.

B. The proprietor of the Kitcheteria in Boise.

C. The proprietor of the Mechanicafe in Boise.

D. The proprietor of the old Chicken Inn in Nampa.

E. None of the above.

3). Why was a pioneer who died on the Oregon Trail dug up in 1909 and reburied in Twin Falls?

A. To move him closer to the graves of his family.

B. To provide the veteran a military funeral.

C. He was an Odd Fellow.

D. Because his grave marker was incorrect.

E. None of the above.

4). Who grew up as Gregory Hallenback?

A. The commander of the Black Sheep Squadron in WWII who won a Medal of Honor.

B. The last man hanged at the old Idaho State Prison.

C. Boxcar Willie.

D. Larry Lujack.

E. Idaho’s third governor, William J. McConnell.

5) What was Alfred Wilke known for?

A. He was the state checker champion of 1938.

B. He sold white leghorn chicks.

C. He manufactured and sold dog food in several states.

D. He sold singing canaries.

E. All of the above.

Answers

Answers1, C

2, B

3, C

4, A

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on November 30, 2019 04:00

November 29, 2019

An Unofficial Post Office

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

In the 1860s it wasn’t wise to carry around a lot of money or gold in Idaho Territory. There was always someone ready to relieve you of it and, perhaps, your life if you hesitated to turn over your wealth.

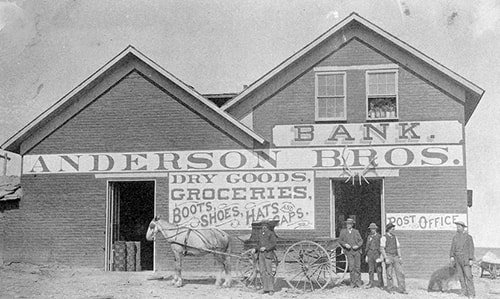

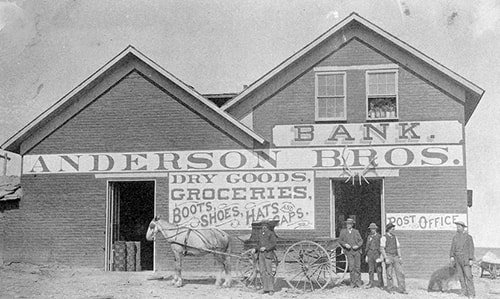

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

In the 1860s it wasn’t wise to carry around a lot of money or gold in Idaho Territory. There was always someone ready to relieve you of it and, perhaps, your life if you hesitated to turn over your wealth.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Published on November 29, 2019 04:00

November 28, 2019

Idaho Plates

Note: Did you know I post an Idaho history story every day? The way Facebook works, you probably only see about one in ten of them unless you go to Speaking of Idaho on Facebook and click the Following tab under the picture. If you select See First under Following, my posts will show up in your feed every day.

License plates are ubiquitous. Everyone who has a car, truck, or motorcycle in Idaho owns at least a couple of them. So why the heck would anyone collect them? Because they’re interesting, and because most of them get thrown away or recycled, so the surviving plates become rarer and rarer as their litter mates succumb. Yes, I just used “litter mates” to describe license plates. Maybe that’s a first and this post will become collectable.

I’m a very minor collector of license plates. I have about 40 or 50, mostly because I keep my personalized plates when it’s time to replace them. And I’m old. There’s that.

Collectors lust for one of Idaho’s first state plates, issued in 1913. There are only a couple of those still around. Idaho issued only single plates for automobiles in 1913 and 1914, ensuring a little extra rarity. Other rarities are early city plates issued by Hailey, Nampa, Payette, Weiser, Lewiston, and Boise, prior to 1913. According to Dan Smith, an acknowledged expert on Idaho license plates, only 19 of those are known to exist.

Did you know there were once hand-painted Idaho license plates? From 1913 to 1924 dealer plates were embossed with the words IDAHO DEALER, but there were no embossed numbers. Dealers had numbers painted on them by professionals. For a time, if you lost your license plate you would be issued a “flat” plate with no number on it, and you were expected to have your number painted on it by a professional. There are only a handful of those around anymore.

The county designators on plates have been around since 1932, but they weren’t all the familiar letter/number combination we see today. In 1932, for instance, Ada county was A1, while Lewis County was K4. It wasn’t until 1945 that the system we’re familiar with today became the standard.

So what’s that oddball license plate you have hanging in your garage worth? It depends. Condition is important as well as rarity. I looked at eBay to see what prices were like. You can get a lot of interesting Idaho plates for less than $50. Someone was asking $500 for a particularly special one. You’ll want to collect them because you find it an interesting hobby, not because you have kids to put through college.

Thanks to Dan Smith for his years of knowledge that went into his Idaho License Plates book, and for the photo. Message me if you want to know how to get a copy. Your local bookstore probably doesn’t have one.

License plates are ubiquitous. Everyone who has a car, truck, or motorcycle in Idaho owns at least a couple of them. So why the heck would anyone collect them? Because they’re interesting, and because most of them get thrown away or recycled, so the surviving plates become rarer and rarer as their litter mates succumb. Yes, I just used “litter mates” to describe license plates. Maybe that’s a first and this post will become collectable.

I’m a very minor collector of license plates. I have about 40 or 50, mostly because I keep my personalized plates when it’s time to replace them. And I’m old. There’s that.

Collectors lust for one of Idaho’s first state plates, issued in 1913. There are only a couple of those still around. Idaho issued only single plates for automobiles in 1913 and 1914, ensuring a little extra rarity. Other rarities are early city plates issued by Hailey, Nampa, Payette, Weiser, Lewiston, and Boise, prior to 1913. According to Dan Smith, an acknowledged expert on Idaho license plates, only 19 of those are known to exist.

Did you know there were once hand-painted Idaho license plates? From 1913 to 1924 dealer plates were embossed with the words IDAHO DEALER, but there were no embossed numbers. Dealers had numbers painted on them by professionals. For a time, if you lost your license plate you would be issued a “flat” plate with no number on it, and you were expected to have your number painted on it by a professional. There are only a handful of those around anymore.

The county designators on plates have been around since 1932, but they weren’t all the familiar letter/number combination we see today. In 1932, for instance, Ada county was A1, while Lewis County was K4. It wasn’t until 1945 that the system we’re familiar with today became the standard.

So what’s that oddball license plate you have hanging in your garage worth? It depends. Condition is important as well as rarity. I looked at eBay to see what prices were like. You can get a lot of interesting Idaho plates for less than $50. Someone was asking $500 for a particularly special one. You’ll want to collect them because you find it an interesting hobby, not because you have kids to put through college.

Thanks to Dan Smith for his years of knowledge that went into his Idaho License Plates book, and for the photo. Message me if you want to know how to get a copy. Your local bookstore probably doesn’t have one.

Published on November 28, 2019 04:00

November 27, 2019

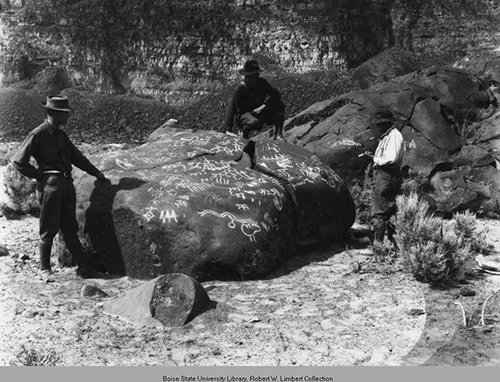

A Rock Writing Don't

Idaho has a plethora of petroglyphs and pictographs. There. I mostly just wanted to use all those alliterative Ps. That alone doesn’t make much a of blog post, so I’d better scramble for a little information so you get your money’s worth.

Idaho has a plethora of petroglyphs and pictographs. There. I mostly just wanted to use all those alliterative Ps. That alone doesn’t make much a of blog post, so I’d better scramble for a little information so you get your money’s worth.First, what’s the difference between petroglyphs and pictographs? Petroglyphs are chipped or scratched into a rock’s surface. Pictographs are painted onto a stone surface using natural dyes and pigments. One handy way to confuse yourself when remembering what the difference is is to remember the “pic” in pictograph should mean that someone “picked” the image into the rock, except that it doesn’t. Helpful? No? That’s just the way my mind works.

Now that you’re about to quit reading because your brain hurts, let me assure you that a public service announcement is coming up. Please stand by.

Famous sites for petroglyphs and pictographs in Idaho include Hells Canyon, the Middle Fork of the Salmon, and numerous sites along the Snake River. If you’d like to see some terrific examples and learn more, visit Celebration Park near Nampa.

I’ve mentioned before that interpreting what is sometimes called “rock writing” is not an exact science. That’s because it’s not really writing. The indigenous people of what is now Idaho did not have a handy alphabet they could use to get their message across. The representations carved into or painted on rock often deviated with the artist. Still, they probably were trying to depict what they saw or tell some kind of story. Maybe you can figure out what they were trying to say. If only there was a way to make the images a little clearer. Hey! What if we traced on top of them with chalk so they would show up better in a photo?

And, here comes the PSA. Don’t do that. It’s illegal in many places and problematic everywhere. It used to be a standard practice, but scientists have learned that chalk dust can bake into the rock over the years helping to obliterate the rock art. It is especially damaging to pictographs, potentially destroying the dyes used to create them and leaving calcium behind in concentrations high enough to make them impossible to carbon date.

Another issue with chalking is that it shows the bias of the chalker. They trace what they “see.” The rock art is often faded so interpretation is sometimes dicey. In one famous example chalking the rock art in a Utah cave created the belief that the indigenous artist was depicting a winged monster, maybe even a pterosaur. That excited people who were eager to prove that dinosaurs and humans existed at the same time.

In 2015, scientists used a portable x-ray florescence device to bring out the original detail on the “winged monster.” It turned out that the rock art was originally a depiction of a couple of four-legged animals, maybe a sheep and a dog.

We humans are very good at identifying figures in clouds and wallpaper stains as various objects, animals, and people. That tendency is called pareidolia. And now I regret that I didn’t use that word in my alliterative first sentence. But, back to that Utah cave. When someone chalked those two critters, they “saw” variations in the color of the rock combined with the rock art that looked like a winged beast. Subsequent chalkers “saw” the same thing because of the original chalker’s pareidolia.

So, no chalking, please. It’s too bad, though. Look how well the rock art shows up in this picture of Map Rock near Murphy. That’s Robert Limbert in the white shirt on the right taking notes. We don’t know who the other two people are, perhaps because Limbert didn’t make note of that. The picture is courtesy of Boise State University Library, Special Collections and Archives.

Published on November 27, 2019 04:00