Rick Just's Blog, page 174

January 15, 2020

Boise's Beautiful Natatorium

Perhaps the first example of magnificent architecture in the Treasure Valley—before the valley had that name—was Boise’s Natatorium. Dedicated in 1892, the “Nat” cost $87,000 to build. Taxpayers in a town of 2500 would have been hard pressed to build a public pool of that grandeur. It was built as a money-making enterprise by the Boise Artesian Hot & Cold Water Company. Soon, houses along Warm Springs Avenue were advertising that they were heated with “Natatorium water.”

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

#boisenatatorium Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

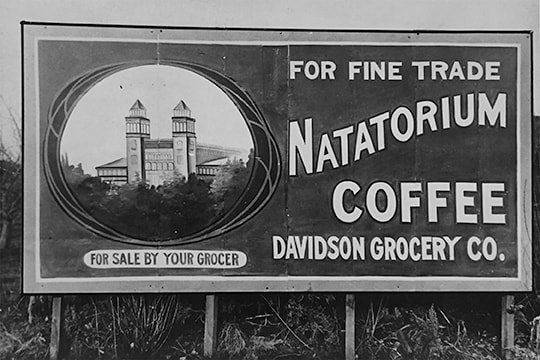

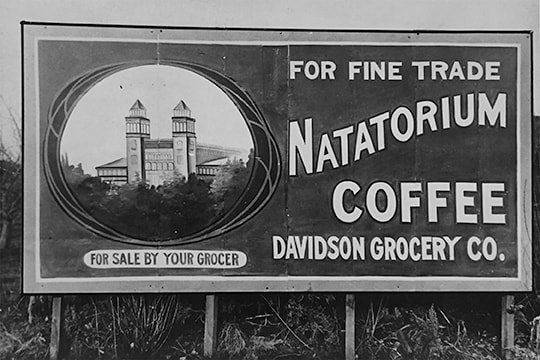

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

#boisenatatorium

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Published on January 15, 2020 04:00

January 14, 2020

The Grand Entrance

If I were to say that 7th Street was the best-known street in Boise, you’d probably have to pause a minute to think just where that is and why some fool thinks it's famous. You could find it between 6th and 8th streets, but the signs won’t be any help. They all say Capitol Boulevard.

It wasn’t always so.

Boise architect and president of the Boise Civic Improvement Association, Charles Wayland, first proposed turning 7th Street into a grand entrance boulevard to the City of Boise. That was in 1914. The proposal was almost an afterthought to his larger idea of channeling the Boise River. Wayland envisioned “saddle paths, footpaths, and parkways” following the course of the newly controlled river with residential areas opening up in what had been floodways. Does that sound a little like today’s Boise Greenbelt?

It wasn’t until 1925 that city officials began to get serious about building that grand entrance. That was the year the new Boise Depot was built, dominating the skyline on the bench directly in front of the capitol building. Those striking architectural icons just begged to have a mile-long boulevard between them. New York architects Carrere and Hastings who designed the mission–style depot pushed for a grand promenade to visually and physically connect the two buildings. A municipal bond made it all happen, with the completion of the Capitol Boulevard Bridge in 1931.

Keeping the view down Capitol Boulevard free from intruding buildings, business signs, and a tangle of traffic control devices has been a constant struggle ever since. It’s a struggle that hasn’t always been won (I’m looking at you, US Bank building), but keeping a vigilant eye on what happens on the boulevard is worth doing to preserve the city’s “grand promenade.” Capitol Boulevard from the Idaho State Capitol building, long before the tall buildings went up. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Capitol Boulevard from the Idaho State Capitol building, long before the tall buildings went up. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

It wasn’t always so.

Boise architect and president of the Boise Civic Improvement Association, Charles Wayland, first proposed turning 7th Street into a grand entrance boulevard to the City of Boise. That was in 1914. The proposal was almost an afterthought to his larger idea of channeling the Boise River. Wayland envisioned “saddle paths, footpaths, and parkways” following the course of the newly controlled river with residential areas opening up in what had been floodways. Does that sound a little like today’s Boise Greenbelt?

It wasn’t until 1925 that city officials began to get serious about building that grand entrance. That was the year the new Boise Depot was built, dominating the skyline on the bench directly in front of the capitol building. Those striking architectural icons just begged to have a mile-long boulevard between them. New York architects Carrere and Hastings who designed the mission–style depot pushed for a grand promenade to visually and physically connect the two buildings. A municipal bond made it all happen, with the completion of the Capitol Boulevard Bridge in 1931.

Keeping the view down Capitol Boulevard free from intruding buildings, business signs, and a tangle of traffic control devices has been a constant struggle ever since. It’s a struggle that hasn’t always been won (I’m looking at you, US Bank building), but keeping a vigilant eye on what happens on the boulevard is worth doing to preserve the city’s “grand promenade.”

Capitol Boulevard from the Idaho State Capitol building, long before the tall buildings went up. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Capitol Boulevard from the Idaho State Capitol building, long before the tall buildings went up. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on January 14, 2020 04:00

January 13, 2020

Write When You get a Chance

George H. Pease seemed like a solid guy. He was the six-foot-six sheriff of Kootenai County in 1898 and he had put together a group of 112 men who were ready to volunteer to fight in the Spanish-American War. Governor Steunenberg took Captain Pease up on his offer, but needed just 50 men, and no officers. So, the Sheriff stayed home. He wouldn’t stay for long.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

Published on January 13, 2020 04:00

January 12, 2020

Those Mechanical Donkeys

What would you call a locomotive without wheels? Loggers called them donkeys. About 20 Willamette donkeys, stationary steam engines that made rolls of steel cable spin, operated in the St. Joe drainage at one time. Their purpose was to drag logs off a mountain and into a holding pond where they could be readied for a trip downriver.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Published on January 12, 2020 04:00

January 11, 2020

Rodeos and Russell

So, I was doing a little research on rodeos the other day because someone had a question about the Caldwell Night Rodeo (which I’ll address in a later post). I dug out my copy of Louise Shadduck’s book,

Rodeo Idaho

. As is usually the case when I set out to research something, I’m presented with rabbit trail after rabbit trail that I want to sniff down. For instance, did you know that Jane Russell came to Idaho to relax after making her first movie,

Outlaw

? It was a 1943 Howard Hughes film about Billy the Kid. Russell spent some time in Island Park where one of the locals pulled together a rodeo at her request. Shadduck’s book has a couple of pictures. Oh, and maybe it’s time I wrote about Shadduck herself, journalist and political powerbroker from Coeur d’Alene.

Shadduck’s book mentioned a couple of contenders for the first American rodeo, one in Prescott, Arizona in 1888 and Cheyenne’s Frontier Days, which started in 1897. She claimed that Idaho’s first rodeo began in 1906. That would become famous as Nampa’s Snake River Stampede. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Shadduck, but I thought I’d do my own quick search through Idaho papers, just to see if I found a mention of an earlier rodeo.

Wow! Right away I came up with one in or around Albion from 1880. Then, I started seeing others in subsequent years from all around the state. In a couple of minutes, I went from elation to minor disappointment. Yes, Idaho had earlier rodeos. Many of them. They weren’t going to count, though, because the early papers were using the word in its original meaning, which is roundup in Spanish. The papers were reporting on the annual roundups of cattle in certain areas, which were annual events. They still are, but newspapers have a lot more to talk about, these days.

So, I hadn’t made a startling discovery about the history of rodeos. Still, it gave me the opportunity to illustrate this post with a publicity photo of Jane Russell from Outlaw, which was probably what drew you to this story in the first place. ‘Fess up!

Shadduck’s book mentioned a couple of contenders for the first American rodeo, one in Prescott, Arizona in 1888 and Cheyenne’s Frontier Days, which started in 1897. She claimed that Idaho’s first rodeo began in 1906. That would become famous as Nampa’s Snake River Stampede. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Shadduck, but I thought I’d do my own quick search through Idaho papers, just to see if I found a mention of an earlier rodeo.

Wow! Right away I came up with one in or around Albion from 1880. Then, I started seeing others in subsequent years from all around the state. In a couple of minutes, I went from elation to minor disappointment. Yes, Idaho had earlier rodeos. Many of them. They weren’t going to count, though, because the early papers were using the word in its original meaning, which is roundup in Spanish. The papers were reporting on the annual roundups of cattle in certain areas, which were annual events. They still are, but newspapers have a lot more to talk about, these days.

So, I hadn’t made a startling discovery about the history of rodeos. Still, it gave me the opportunity to illustrate this post with a publicity photo of Jane Russell from Outlaw, which was probably what drew you to this story in the first place. ‘Fess up!

Published on January 11, 2020 04:00

January 10, 2020

What's Your Number?

Time for another then and now feature.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

#idahohistory #idahoareacode

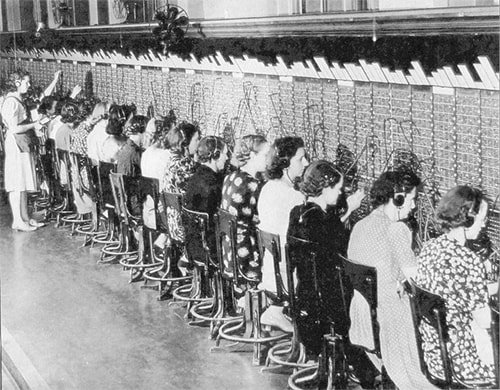

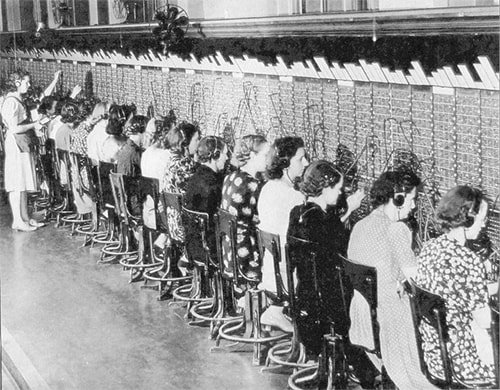

Telephone operators in Pocatello, date unknown.

Telephone operators in Pocatello, date unknown.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

#idahohistory #idahoareacode

Telephone operators in Pocatello, date unknown.

Telephone operators in Pocatello, date unknown.

Published on January 10, 2020 04:00

January 9, 2020

Boise's First "Buzz Wagon" Accident

Note: This post originally appeared as one of my columns in The Idaho Press.

The 1907 headline read “Buzz Wagon Parties Now a Fad.” The Idaho Statesman hadn’t yet settled on what to call automobiles. “Buzz wagon” didn’t catch on, fading as fast as the fad.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

The 1907 headline read “Buzz Wagon Parties Now a Fad.” The Idaho Statesman hadn’t yet settled on what to call automobiles. “Buzz wagon” didn’t catch on, fading as fast as the fad.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst.

Published on January 09, 2020 04:00

January 8, 2020

A Little Leg Room in Malad

There is a lot of history buried in cemeteries, some of it a little quirky. The Oneida County Relic Preservation and Historical Society in Malad City has a story on their website, written by Sue Thomas that lives up to that label.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

#idahohistory #maladidaho #maladcemetery

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

#idahohistory #maladidaho #maladcemetery

Published on January 08, 2020 04:00

January 7, 2020

What Became of Idaho's Richest Man?

Jose “Joe” Bengoechea was a Basque sheepherder. Maybe it should be said that he was the Basque sheepherder. He came to the US in 1881 at age 20. He started herding sheep in Nevada, saving his money, and began buying sheep. His herds grew and he helped others from the Basque Country to immigrate.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post. Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.  The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.  The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

Published on January 07, 2020 04:00

January 6, 2020

Where's the Lake?

Since my posts on Chicken Dinner Road and Protest Road, I’ve received several requests to tell how other roads got their names. I can’t research them all right away, but one did catch my attention. It was about Lake Hazel Road that runs from Maple Grove Road in Boise to S. Robinson Road in Nampa. The request wasn’t about how the road got its name. They wondered where the heck the lake was?

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

#idahohistory #lakehazel #lakehazelroad #chickendinnerroad #protestroad

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

#idahohistory #lakehazel #lakehazelroad #chickendinnerroad #protestroad

Published on January 06, 2020 04:00