Rick Just's Blog, page 168

March 15, 2020

The Spanish Flu

I know, you're getting tired of hearing about the current pandemic. Maybe reading about one more than a hundred years ago will be of interest.

In September of 1918, Treasure Valley residents were focused on the war raging in Europe. They were involved with drives to raise money for that effort and young men were leaving regularly for the fight. But there were lesser headlines in the papers that were starting to capture the attention of readers. There was a plague moving into the United States from Europe. It was sometimes called the Army Plague, because it was infecting army camps and shipyards where returning soldiers were billeted. It would soon be known widely as the Spanish Influenza.

The Idaho Statesman’s medical columnist, Dr. William Brady wasn’t much concerned about it. He was certain it would be no worse than any other flu that had come and gone in the preceding decades. He recommended that his readers prepare for it by taking long walks out of doors. Getting fresh air and plenty of exercise would not prevent the flu, but it would give one the strength and vigor needed to combat it.

The first reports that really hit home were of area soldiers who were quarantined at their bases, either in training or on their way home. Sickness followed for many, and death for a few. Reports of traveling citizens in eastern cities coming down with the disease soon followed.

On October 2, 1918, the Spanish Flu had hit the valley. Six families, consisting of 15 persons in and near Caldwell came down with the disease. The carrier was identified as a woman from Missouri who had visited the families. Quarantines were put in place.

Most of the stories about the flu in local papers were from back east where cases were growing rapidly. A health commissioner in New York was recommending gauze or chiffon masks. Another helpful suggestion he had was to avoid kissing unless you did it through a handkerchief.

As concern about the Spanish Influenza mounted, advertisements started popping up offering preventions, cures, or symptomatic relief. Tanlac Laxative Tablets were said to contain the very elements needed by the system to give it fighting strength. Lister’s Anteseptic Solution was billed as “First Aid to Prevent Spanish Influenza.” This on the same page as an ad for Danderine, claiming that dandruff makes hair fall out. These were alongside ads such as that from the California Fig Syrup Company lauding their product as a cure when your child was cross, irritable, feverish, or had bad breath. Another ad went after the flu fear market, claiming Kondon’s Catarrhal Jelly applied inside the nose would give antiseptic relief.

By October 6, a boy in Star had come down with the flu. On October 9, Dr. E.T. Biwer, secretary of the state board of health, ordered a ban on all public gatherings, including theaters, dance halls, churches, the Natatorium, Liberty Loan rallies (raising money for the war), and political rallies. Only public and private schools were exempted.

This ruffled a lot of feathers. Lodge representatives, members of men’s and women’s clubs, ministers, and pool hall owners made the phone ring constantly at the state board of health, a usually quiet office. Dr. Biwer stood firm, saying that only open-air meetings and private and public schools were exempt.

The Boise Ministerial Association took another tact, saying that if there was danger enough to close churches, then schools should also be closed.

Meanwhile, the Boise City Council questioned the state official’s authority to ban meetings and asked for a legal opinion. An opinion came quickly, but in the form of a Statesmen editorial on October 12. The editors opined that such stringent measures should not be put into effect until “there were 400 or 500 cases, or at least more than our physicians could control.”

Meanwhile, the state began citing pool hall owners for defying the order.

On October 13, the Statesman reported 90 cases of influenza in the state. On October 15, the secretary of the board of health ruled that a state land board meeting should be closed after seeing that 25 people had showed up for the event. That was the same day the paper reported Boise’s first influenza cases.

Mrs. Ray Shawver, 1317 North Twenty-second Street was named as the first person in Boise to catch the disease. Her house was quarantined, and a yellow flag was put out front to visually mark it. When the Statesman next reported state statistics, the number of influenza cases had risen to 161. New cases were reported in Star and Nampa.

It was about this time that the motion picture industry suspended delivery of films to theaters to assure that patrons would not be gathering in infectious groups.

On October 16 the Statesman reported a statewide total of 209 cases. On the 17th, the number was up to 471. On the 18th, the story broke that there were 300 cases of Spanish Influenza in the town of Nez Perce, population 600.

Ada County Civil Defense began gathering the names of nurses, calling for “graduate nurses, pupil nurses, undergraduate nurses, trained attendants, practical nurses and midwives.”

On October 19, the state statistics came in again. Ada county had only 15 cases, but there were 1008 infected statewide. Seven had died.

On October 20, the state health board gave a general closing order for schools statewide. Courts began rescheduling cases.

A rumor spread quickly that Boise was under quarantine, as some smaller towns such as Challis, were. The secretary of the state board of health moved quickly to quash that one.

On the 23rd the statewide toll of confirmed cases reached 1711.

Boise dragged its feet on closing schools. Even so it was costing $20,000 a day statewide to pay teachers who were not working.

By October 28 the Statesman reported 11 new cases in the city, and six deaths in a single day. St. Anthony and Rexburg were under quarantine. Halloween was cancelled in Boise.

The Spanish Influenza would ebb and flow over the coming months until The Statesman was able to declare in a headline on January 19, 1919, “Schools Free of Disease.”

Because of haphazard reporting it is difficult to determine an exact number for those who succumbed to the disease. In Boise, it was probably about 75. Other areas of the state were hit much harder. Paris, Idaho, according to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, had a mortality rate of nearly 50 percent. Native Americans were hit especially hard in Idaho, with 75 deaths out of a population of just over 4,000. Worldwide estimates are between 20 and 50 million who succumbed to the disease.

One of the least helpful tips those trying to avoid the Spanish Flu got was that they should use caution while kissing. Kissing through a handkerchief was the recommended method.

One of the least helpful tips those trying to avoid the Spanish Flu got was that they should use caution while kissing. Kissing through a handkerchief was the recommended method.

In September of 1918, Treasure Valley residents were focused on the war raging in Europe. They were involved with drives to raise money for that effort and young men were leaving regularly for the fight. But there were lesser headlines in the papers that were starting to capture the attention of readers. There was a plague moving into the United States from Europe. It was sometimes called the Army Plague, because it was infecting army camps and shipyards where returning soldiers were billeted. It would soon be known widely as the Spanish Influenza.

The Idaho Statesman’s medical columnist, Dr. William Brady wasn’t much concerned about it. He was certain it would be no worse than any other flu that had come and gone in the preceding decades. He recommended that his readers prepare for it by taking long walks out of doors. Getting fresh air and plenty of exercise would not prevent the flu, but it would give one the strength and vigor needed to combat it.

The first reports that really hit home were of area soldiers who were quarantined at their bases, either in training or on their way home. Sickness followed for many, and death for a few. Reports of traveling citizens in eastern cities coming down with the disease soon followed.

On October 2, 1918, the Spanish Flu had hit the valley. Six families, consisting of 15 persons in and near Caldwell came down with the disease. The carrier was identified as a woman from Missouri who had visited the families. Quarantines were put in place.

Most of the stories about the flu in local papers were from back east where cases were growing rapidly. A health commissioner in New York was recommending gauze or chiffon masks. Another helpful suggestion he had was to avoid kissing unless you did it through a handkerchief.

As concern about the Spanish Influenza mounted, advertisements started popping up offering preventions, cures, or symptomatic relief. Tanlac Laxative Tablets were said to contain the very elements needed by the system to give it fighting strength. Lister’s Anteseptic Solution was billed as “First Aid to Prevent Spanish Influenza.” This on the same page as an ad for Danderine, claiming that dandruff makes hair fall out. These were alongside ads such as that from the California Fig Syrup Company lauding their product as a cure when your child was cross, irritable, feverish, or had bad breath. Another ad went after the flu fear market, claiming Kondon’s Catarrhal Jelly applied inside the nose would give antiseptic relief.

By October 6, a boy in Star had come down with the flu. On October 9, Dr. E.T. Biwer, secretary of the state board of health, ordered a ban on all public gatherings, including theaters, dance halls, churches, the Natatorium, Liberty Loan rallies (raising money for the war), and political rallies. Only public and private schools were exempted.

This ruffled a lot of feathers. Lodge representatives, members of men’s and women’s clubs, ministers, and pool hall owners made the phone ring constantly at the state board of health, a usually quiet office. Dr. Biwer stood firm, saying that only open-air meetings and private and public schools were exempt.

The Boise Ministerial Association took another tact, saying that if there was danger enough to close churches, then schools should also be closed.

Meanwhile, the Boise City Council questioned the state official’s authority to ban meetings and asked for a legal opinion. An opinion came quickly, but in the form of a Statesmen editorial on October 12. The editors opined that such stringent measures should not be put into effect until “there were 400 or 500 cases, or at least more than our physicians could control.”

Meanwhile, the state began citing pool hall owners for defying the order.

On October 13, the Statesman reported 90 cases of influenza in the state. On October 15, the secretary of the board of health ruled that a state land board meeting should be closed after seeing that 25 people had showed up for the event. That was the same day the paper reported Boise’s first influenza cases.

Mrs. Ray Shawver, 1317 North Twenty-second Street was named as the first person in Boise to catch the disease. Her house was quarantined, and a yellow flag was put out front to visually mark it. When the Statesman next reported state statistics, the number of influenza cases had risen to 161. New cases were reported in Star and Nampa.

It was about this time that the motion picture industry suspended delivery of films to theaters to assure that patrons would not be gathering in infectious groups.

On October 16 the Statesman reported a statewide total of 209 cases. On the 17th, the number was up to 471. On the 18th, the story broke that there were 300 cases of Spanish Influenza in the town of Nez Perce, population 600.

Ada County Civil Defense began gathering the names of nurses, calling for “graduate nurses, pupil nurses, undergraduate nurses, trained attendants, practical nurses and midwives.”

On October 19, the state statistics came in again. Ada county had only 15 cases, but there were 1008 infected statewide. Seven had died.

On October 20, the state health board gave a general closing order for schools statewide. Courts began rescheduling cases.

A rumor spread quickly that Boise was under quarantine, as some smaller towns such as Challis, were. The secretary of the state board of health moved quickly to quash that one.

On the 23rd the statewide toll of confirmed cases reached 1711.

Boise dragged its feet on closing schools. Even so it was costing $20,000 a day statewide to pay teachers who were not working.

By October 28 the Statesman reported 11 new cases in the city, and six deaths in a single day. St. Anthony and Rexburg were under quarantine. Halloween was cancelled in Boise.

The Spanish Influenza would ebb and flow over the coming months until The Statesman was able to declare in a headline on January 19, 1919, “Schools Free of Disease.”

Because of haphazard reporting it is difficult to determine an exact number for those who succumbed to the disease. In Boise, it was probably about 75. Other areas of the state were hit much harder. Paris, Idaho, according to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, had a mortality rate of nearly 50 percent. Native Americans were hit especially hard in Idaho, with 75 deaths out of a population of just over 4,000. Worldwide estimates are between 20 and 50 million who succumbed to the disease.

One of the least helpful tips those trying to avoid the Spanish Flu got was that they should use caution while kissing. Kissing through a handkerchief was the recommended method.

One of the least helpful tips those trying to avoid the Spanish Flu got was that they should use caution while kissing. Kissing through a handkerchief was the recommended method.

Published on March 15, 2020 04:00

March 14, 2020

Idaho's First Radio Station

This story starts in September of 1917, when Harry Redeker was hired as a chemistry and physics teacher at Boise High School. In the evenings, he taught Morse Code to young men who were about to head into the maw of World War One.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, this time broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

On July 18, 1922, radio station KFAU was first licensed, thus today’s anniversary. It started broadcasting on July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser, and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU so that it could become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Idaho Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings over the years, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the fate of the station, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September, 1928, KFAU was sold to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kido.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School, shown in the photo and inset below, is long gone.

Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation, Inc. for their help on this story.

After the war, Redeker got his amateur radio license and continued the classes, this time broadcasting on station 7YA starting in December 1919. The student station eventually began broadcasting music and speech, thanks to improved equipment and technology.

On July 18, 1922, radio station KFAU was first licensed, thus today’s anniversary. It started broadcasting on July 20.

There wasn’t a lot of competition on the radio dial, so the station had some impact. On July 30, 1922, the Idaho Statesman reported that listeners could clearly hear the station in Kuna, Nampa, Caldwell, Parma, Payette, Weiser, and Ontario. Some reported hearing it in Twin Falls and St. Anthony. Listeners heard live music performed by local musicians, religious broadcasts, and a speech by Sen. William Borah.

Under Redeker’s guidance and with community support the station grew, increasing its power to 4,000 watts during the day and 2,000 watts at night in 1926. Daytime production was handled by Boise High School students, while the Boise Chamber of Commerce took over at night. Notably, the Chamber also began financing the radio station.

By 1927 the station had become so popular that there was pressure on the school board to sell KFAU so that it could become Idaho’s first commercial station. The Idaho Statesman, which had run dozens of articles and program listings over the years, was making plans of its own to start a commercial radio station, though those plans never reached fruition.

With increasing controversy over the fate of the station, some of the fun had gone out of the project for Harry Redeker. He took a job in California.

In September, 1928, KFAU was sold to Curtis G. Phillips and Frank Hill. The call letters changed to KIDO in November of 1928. From that time forward, Phillips went by the nickname “Kido.”

KIDO still broadcasts from Boise today, although that studio in Boise High School, shown in the photo and inset below, is long gone.

Thanks to Art Gregory and the History of Idaho Broadcasting Foundation, Inc. for their help on this story.

Published on March 14, 2020 04:00

March 13, 2020

A Fatal Flight

The war was over. This time, it was the one in Korea. The men were coming home. Getting them there was a logistics operation not unlike the war itself. The U.S. Army hired private contractors to airlift soldiers home from the West Coast.

On January 7, 1953 men were lined up by last name, waiting for a flight to various facilities across the country from which they would eventually reach their scattered homes. The young men with last names starting with H, J, or K were eager to get on the plane for the flight designated 1-6-6A at Boeing Field in Seattle. They were to fly to Fort Jackson, South Carolina to receive their discharge papers.

The pilot of the chartered Curtiss C-46F was 28-year-old Captain Lawrence Crawford. He had worked for Associated Air Transport for a couple of years and had nearly 5,000 hours in the air. Co Pilot Maxwell Perkins, 32, had flown about 3,500 hours, many of them in C-46s.

Dorthy Davis, 21, had zero hours in the air. She was the newly hired stewardess looking forward to her first flight.

PFC Ernest Kinsey, of Madison, Florida, was in line to board the plane. They counted off 37 passengers, stopping right before Kinsey. He’d have to take another flight. That plane would land in Salt Lake City for an oil line repair. It was there that he and his fellow soldiers learned that flight 1-6-6A was missing. When asked by a newspaper reporter how he felt, he said, “Just Lucky, I guess.”

The C-46F Commando was schedule to refuel in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The weather for the nighttime flight didn’t seem threatening, though the pilots were warned of the possibility of ice. Some three hours after taking off in Seattle, the pilots checked in at 13,000 feet over Malad City, Idaho at 3:58 am. They were scheduled to report in again at 4:45 over Rock Springs. That call never came.

A few minutes after the check-in at Malad, the plane crashed into the side of a mountain at an altitude of 8,545 about 8 miles from Fish Haven, near Bear Lake. We don’t know what went wrong. The engines were both in good shape and the deicing mechanisms were working. The FAA report would ultimately list the “inadvertent descent into an area of turbulence and icing” as the cause of the crash.

What we do know is that there were no survivors. It would be June before a recovery team could reach the crash site and retrieve the bodies.

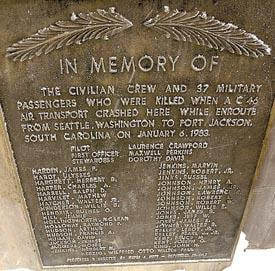

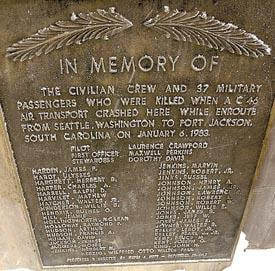

This sad end to 37 men coming home from war with soaring hearts, and their three crewmembers, is commemorated at the crash site with a brass plaque listing all their names.

A C46F Commando much like the one on flight 1-6-6A.

A C46F Commando much like the one on flight 1-6-6A.  The brass plaque at the crash site.

The brass plaque at the crash site.

On January 7, 1953 men were lined up by last name, waiting for a flight to various facilities across the country from which they would eventually reach their scattered homes. The young men with last names starting with H, J, or K were eager to get on the plane for the flight designated 1-6-6A at Boeing Field in Seattle. They were to fly to Fort Jackson, South Carolina to receive their discharge papers.

The pilot of the chartered Curtiss C-46F was 28-year-old Captain Lawrence Crawford. He had worked for Associated Air Transport for a couple of years and had nearly 5,000 hours in the air. Co Pilot Maxwell Perkins, 32, had flown about 3,500 hours, many of them in C-46s.

Dorthy Davis, 21, had zero hours in the air. She was the newly hired stewardess looking forward to her first flight.

PFC Ernest Kinsey, of Madison, Florida, was in line to board the plane. They counted off 37 passengers, stopping right before Kinsey. He’d have to take another flight. That plane would land in Salt Lake City for an oil line repair. It was there that he and his fellow soldiers learned that flight 1-6-6A was missing. When asked by a newspaper reporter how he felt, he said, “Just Lucky, I guess.”

The C-46F Commando was schedule to refuel in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The weather for the nighttime flight didn’t seem threatening, though the pilots were warned of the possibility of ice. Some three hours after taking off in Seattle, the pilots checked in at 13,000 feet over Malad City, Idaho at 3:58 am. They were scheduled to report in again at 4:45 over Rock Springs. That call never came.

A few minutes after the check-in at Malad, the plane crashed into the side of a mountain at an altitude of 8,545 about 8 miles from Fish Haven, near Bear Lake. We don’t know what went wrong. The engines were both in good shape and the deicing mechanisms were working. The FAA report would ultimately list the “inadvertent descent into an area of turbulence and icing” as the cause of the crash.

What we do know is that there were no survivors. It would be June before a recovery team could reach the crash site and retrieve the bodies.

This sad end to 37 men coming home from war with soaring hearts, and their three crewmembers, is commemorated at the crash site with a brass plaque listing all their names.

A C46F Commando much like the one on flight 1-6-6A.

A C46F Commando much like the one on flight 1-6-6A.  The brass plaque at the crash site.

The brass plaque at the crash site.

Published on March 13, 2020 04:00

March 12, 2020

Jackson Sundown

Did you ever play cowboys and Indians as a kid? Today’s story is about a man who wasn’t playing. He was a cowboy and an Indian.

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn was a nephew of Nez Perce Chief Joseph. He was 14 in 1877 when the flight of the Nez Perce took place across much of Idaho and parts of Oregon, Wyoming, and Montana. His uncle famously surrendered with the eloquent “I will fight no more forever” speech at Bear Paws Battlefield in Montana.

Meanwhile, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, wounded, went with a small group of Nez Perce into Canada where he lived for a couple of years with Sitting Bull’s Sioux.

He lived in Washington and Montana, gaining a reputation as a skilled horseman, and a new name, Jackson Sundown, before moving to Idaho in 1910. His skills atop a bucking bronco became so well-known that other riders would simply pull out of the competition when they heard Sundown had signed up. At least one rodeo manager solved that problem by paying Sundown $50 a day for exhibition bronc riding.

In 1911, Sundown along with George Fletcher, who was black, and John Spain, a white cowboy, competed at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in a famous multi-racial showdown. Ken Kesey told that story in his 1995 book, Last Go Round .

In 1915, at the age of 52, Jackson Sundown came in only third in bronc riding at the Pendleton Roundup. He decided to retire. But the next year, Alexander Phimister Proctor, a noted sculptor who was working on a sculpture of Sundown at the time talked the man into riding just once more. Jackson won the saddle bronc competition that day at the age of 53. Many of his competitors were half that age or less.

Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Culdesac, Idaho. He was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2006.

#kenkesey #jacksonsundown The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection

Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn was a nephew of Nez Perce Chief Joseph. He was 14 in 1877 when the flight of the Nez Perce took place across much of Idaho and parts of Oregon, Wyoming, and Montana. His uncle famously surrendered with the eloquent “I will fight no more forever” speech at Bear Paws Battlefield in Montana.

Meanwhile, Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn, wounded, went with a small group of Nez Perce into Canada where he lived for a couple of years with Sitting Bull’s Sioux.

He lived in Washington and Montana, gaining a reputation as a skilled horseman, and a new name, Jackson Sundown, before moving to Idaho in 1910. His skills atop a bucking bronco became so well-known that other riders would simply pull out of the competition when they heard Sundown had signed up. At least one rodeo manager solved that problem by paying Sundown $50 a day for exhibition bronc riding.

In 1911, Sundown along with George Fletcher, who was black, and John Spain, a white cowboy, competed at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in a famous multi-racial showdown. Ken Kesey told that story in his 1995 book, Last Go Round .

In 1915, at the age of 52, Jackson Sundown came in only third in bronc riding at the Pendleton Roundup. He decided to retire. But the next year, Alexander Phimister Proctor, a noted sculptor who was working on a sculpture of Sundown at the time talked the man into riding just once more. Jackson won the saddle bronc competition that day at the age of 53. Many of his competitors were half that age or less.

Jackson Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923. He was buried at Slickpoo Mission Cemetery near Culdesac, Idaho. He was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2006.

#kenkesey #jacksonsundown

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection

The picture is Lora Remington Potvin with Jackson Sundown in traditional dress posing in front of the 1920 sculpture called “The Bronc Buster,” for which Jackson Sundown was the model. The sculpture is in Civic Center Park in Denver. The sculptor, Alexander P. Proctor, lived in Lewiston in 1916 and 1917, according to Steve Branting. The photo is courtesy of Steve Branting and Edmond and Lora Potvin Collection

Published on March 12, 2020 04:00

March 11, 2020

On Location: Idaho

In spite of the grand scenery, few movies have been shot in Idaho. That’s largely for logistical reasons, i.e., lack of motels in remote regions, lack of local production talent, lack of roads, etc.

Here are some movies that were shot in Idaho or had scenes in Idaho. Note that the links lead to an Amazon page about each movie. I get a few pennies if you buy something from Amazon after following that link. I don’t care if you buy anything, Amazon just wants you to know.

1923, The Grubstake, written and directed by Nell Shipman, she also starred in it. This and a series of short movies were shot at Priest Lake.

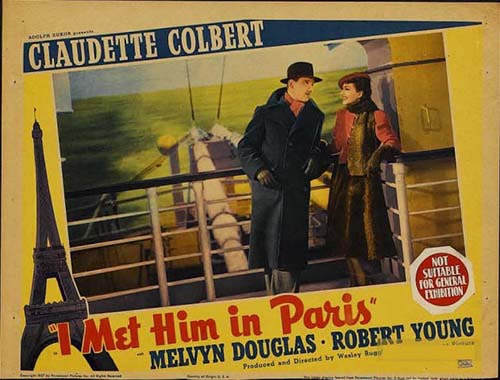

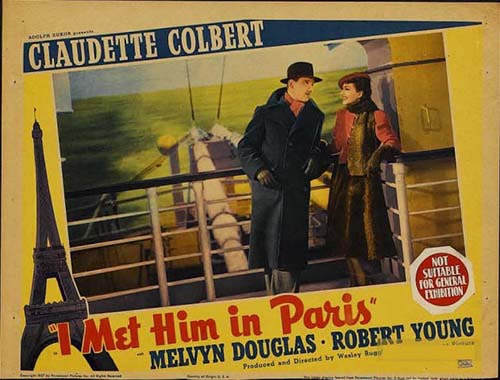

1936, I Met Him in Paris , starring Claudette Colbert, Melvyn Douglas, and Robert Young. Shot in Sun Valley, it was the first movie to take advantage of the new resort.

1936, Come and Get It, starring Edward Arnold, Joel McCrea, Frances Farmer, and Walter Brennan. A logging film where some of the exterior scenes were shot along the Clearwater.

1940, Northwest Passage , Starring Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey. Shot near McCall at what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. See previous post about the movie.

1941, Sun Valley Serenade , starring Sonja Henie, John Payne, and Glenn Miller. Shot partially in Sun Valley, you can still see it showing there every day.

1947, The Unconquered, starring Gary Cooper, Ward bond, and Paulette Goddard. Set in the 1760s, Fremont County became Virginia and other East Coast locations in this Cecil B. DeMille movie, though most of the “outdoor” scenes were shot on a Hollywood sound stage.

1950, Duchess of Idaho , starring Esther Williams, Van Johnson, and John Lund. The romantic comedy was shot in Sun Valley, where Esther Williams trades her trademark swimsuit for a ski parka.

1953, How to Marry a Millionaire , starring Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable, and Lauren Bacall. Allegedly some scenes were shot in Idaho, though this is suspect. The movie largely takes place in New York City.

1955, Storm Fear , starring Cornel Wilde, Jean Wallace, and Dan Duryea was a crime noir filmed partly in Sun Valley.

1956, Bus Stop , starring Marilyn Monroe, Don Murray, and Arthur O’Connell. Some scenes were shot in Sun Valley and the Wood River Valley. The movie was a highly acclaimed drama in which Monroe sang “That Old Black Magic.”

1959, Last Clear Chance, starring no one, really. It was a film sponsored by Union Pacific Railroad to promote safety at railroad crossings. It’s of some interest because it was shot in Idaho and William Agee, 21 at the time, appeared in it. Agee was later the CEO of Boise Cascade, Bendix, and finally Morrison Knudsen at various times. Many blame him for the demise of MK.

1965, Ski Party , starring Fankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman was a sex comedy shot in and around Sun Valley. It is noted (?) for the music in the film, including Lesley Gore’s “Sunshine, Lollipops, and Rainbows,” James brown’s “I Got You (I Feel Good,” and a couple of songs sung by Avalon. It was the last in a series of teen films that included Beach Blanket Bingo.

1973, Idaho Transfer , starring some people you’ve never heard of and Keith Carradine. It was an apocalyptic science fiction film directed by Peter Fonda. Most of the film was shot at Craters of the Moon, with some scenes film at Bruneau Dunes State Park. One critic called it a “usless piece of drivel about an obnoxious group of teens.” (Jay Robert Nash, The Motion Picture Guide).

1975, Breakheart Pass , starring Charles Bronson, Richard Crenna, Jill Ireland, and Ben Johnson. Filmed in North Idaho around Pierce. Many of the Native American extras were Nez Perce from Lapwai. It was notable as the last movie for veteran stuntman Yakima Canutt.

1980, Bronco Billy , starring Clint Eastwood, Sondra Locke, and Scatman Crothers. Filmed in and around Boise, Eagle, and Meridian. A lot of local talent became extras in the movie.

1980, Heaven’s Gate, starring Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, John Hurt, Jeff Bridges, Willem Dafoe, Micky Rourke, Joseph Cotton, and others. Shot partly in Wallace, it is best known for being a big flop. It cost around $44 million and brought in less than $4 million at the box office. Subsequent re-edits have received some acclaim.

1985, Pale Rider , starring, directed, and produced by Clint Eastwood. It was shot mostly in the Boulder Mountains in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. It was the first big-budget western shot after Heaven’s Gate and its impact was about 180 degrees from that failure. It received critical acclaim and pulled in more than $41 million on a budget just shy of $7 million.

1988, Moving, starring Richard Pryor. The setting is Boise, but only a couple of shots were actually filmed there.

1990, Ghost Dad , directed by Sidney Poitier and starry Bill Cosby. It was a seriously unfunny film, according to reviews. Some scenes MAY have been shot in Idaho.

1991, Talent for the Game, starring Edward James Olmos and Lorraine Bracco, used Genesee as its backdrop, with some scenes shot in Kellogg. It went quickly to video.

1992, Dark Horse , starring Ed Begley Jr, Samantha Eggar, Ari Meyers, Mimi Rogers, and Tab Hunter. Hunter wrote the original story. David Hemmings directed the film, which was shot not far from his home in Sun Valley.

1992, Toys , starring Robin Williams, Michael Gambon, Joan Cusack, Robin Wright, and LL Cool J. Directed by Barry Levinson, much of it was filmed in and around Moscow. Levinson was nominated for a Razzie for the film. Un, not an honor.

1997, Dante’s Peak , starring Pierce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton. Wallace became a town covered in ash for this (putting on my reviewer hat, now) ridiculous movie. It did well financially in spite of mostly negative reviews.

1998, Smoke Signals , starring Irene Bedard, Adam Bent, and Evan Adams. Shot on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation around Worley and Plummer and based on a short story by Sherman Alexie. It was an all native production that won numerous awards.

1998, Breakfast of Champions, starring Bruce Willis, Albert Finney, Nick Nolte, Barbara Hershey, and Lucas Haas. Based loosely on the Kurt Vonnegut novel of the same name it was shot in and around Twin Falls. It was a box office bomb that was widely panned by critics.

1999, Wild Wild West, starring Will Smith and Kevin Kline. This steampunk western comedy was loosely a take-off from the 1960s TV series of the same name. Some of the train exteriors were filmed on the old Camas Prairie Railroad, which has an abundance of dramatic trestles.

2001, Town and Country , starring Warren Beatty, Diane Keaton, Goldie Hawn, Gary Shandling, Andie MacDowell, Nastassja Kinski, and Charlton Heston. In spite of its stellar cast and a rewrite by Buck Henry, this one was a legendary flop, costing more than $100 million to make and bringing in just over $10 million. It was shot partially in Sun Valley.

2003, Shredder , starring Scott Weinger and Lindsey McKeon was a slasher film sohot at Silver Mounta Ski Resort, Kellogg.

2004, Napoleon Dynamite , starring Jon Heder, Efren Ramirez, Aaron Ruell, Jon Gries, and Sandy Martin. Shot on a budget of about $400,000, this collaboration between BYU film students using mostly friends as actors earned about $45 million. Written by Preston natives Jared and Jerusha Hess, and directed by Jared, it remains a cult classic.

2012, The Mooring , starring Hallie Todd, and others. This was a straight to DVD movie that was shot in Northern Idaho and Eastern Washington. Lake Coeur d’Alene, Chatcolet Lake, and the St. Joe show up in the film, along with camping scenes from Rocky Point and Plummer point in Heyburn State Park.

And, what have I missed? Do you know of some scenes that were shot in Idaho, or maybe an entire movie? Send me details or comment.

I Met Him in Paris would seem to be all about Paris. It was shot largely in Sun Valley.

I Met Him in Paris would seem to be all about Paris. It was shot largely in Sun Valley.

Here are some movies that were shot in Idaho or had scenes in Idaho. Note that the links lead to an Amazon page about each movie. I get a few pennies if you buy something from Amazon after following that link. I don’t care if you buy anything, Amazon just wants you to know.

1923, The Grubstake, written and directed by Nell Shipman, she also starred in it. This and a series of short movies were shot at Priest Lake.

1936, I Met Him in Paris , starring Claudette Colbert, Melvyn Douglas, and Robert Young. Shot in Sun Valley, it was the first movie to take advantage of the new resort.

1936, Come and Get It, starring Edward Arnold, Joel McCrea, Frances Farmer, and Walter Brennan. A logging film where some of the exterior scenes were shot along the Clearwater.

1940, Northwest Passage , Starring Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey. Shot near McCall at what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. See previous post about the movie.

1941, Sun Valley Serenade , starring Sonja Henie, John Payne, and Glenn Miller. Shot partially in Sun Valley, you can still see it showing there every day.

1947, The Unconquered, starring Gary Cooper, Ward bond, and Paulette Goddard. Set in the 1760s, Fremont County became Virginia and other East Coast locations in this Cecil B. DeMille movie, though most of the “outdoor” scenes were shot on a Hollywood sound stage.

1950, Duchess of Idaho , starring Esther Williams, Van Johnson, and John Lund. The romantic comedy was shot in Sun Valley, where Esther Williams trades her trademark swimsuit for a ski parka.

1953, How to Marry a Millionaire , starring Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable, and Lauren Bacall. Allegedly some scenes were shot in Idaho, though this is suspect. The movie largely takes place in New York City.

1955, Storm Fear , starring Cornel Wilde, Jean Wallace, and Dan Duryea was a crime noir filmed partly in Sun Valley.

1956, Bus Stop , starring Marilyn Monroe, Don Murray, and Arthur O’Connell. Some scenes were shot in Sun Valley and the Wood River Valley. The movie was a highly acclaimed drama in which Monroe sang “That Old Black Magic.”

1959, Last Clear Chance, starring no one, really. It was a film sponsored by Union Pacific Railroad to promote safety at railroad crossings. It’s of some interest because it was shot in Idaho and William Agee, 21 at the time, appeared in it. Agee was later the CEO of Boise Cascade, Bendix, and finally Morrison Knudsen at various times. Many blame him for the demise of MK.

1965, Ski Party , starring Fankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman was a sex comedy shot in and around Sun Valley. It is noted (?) for the music in the film, including Lesley Gore’s “Sunshine, Lollipops, and Rainbows,” James brown’s “I Got You (I Feel Good,” and a couple of songs sung by Avalon. It was the last in a series of teen films that included Beach Blanket Bingo.

1973, Idaho Transfer , starring some people you’ve never heard of and Keith Carradine. It was an apocalyptic science fiction film directed by Peter Fonda. Most of the film was shot at Craters of the Moon, with some scenes film at Bruneau Dunes State Park. One critic called it a “usless piece of drivel about an obnoxious group of teens.” (Jay Robert Nash, The Motion Picture Guide).

1975, Breakheart Pass , starring Charles Bronson, Richard Crenna, Jill Ireland, and Ben Johnson. Filmed in North Idaho around Pierce. Many of the Native American extras were Nez Perce from Lapwai. It was notable as the last movie for veteran stuntman Yakima Canutt.

1980, Bronco Billy , starring Clint Eastwood, Sondra Locke, and Scatman Crothers. Filmed in and around Boise, Eagle, and Meridian. A lot of local talent became extras in the movie.

1980, Heaven’s Gate, starring Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, John Hurt, Jeff Bridges, Willem Dafoe, Micky Rourke, Joseph Cotton, and others. Shot partly in Wallace, it is best known for being a big flop. It cost around $44 million and brought in less than $4 million at the box office. Subsequent re-edits have received some acclaim.

1985, Pale Rider , starring, directed, and produced by Clint Eastwood. It was shot mostly in the Boulder Mountains in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. It was the first big-budget western shot after Heaven’s Gate and its impact was about 180 degrees from that failure. It received critical acclaim and pulled in more than $41 million on a budget just shy of $7 million.

1988, Moving, starring Richard Pryor. The setting is Boise, but only a couple of shots were actually filmed there.

1990, Ghost Dad , directed by Sidney Poitier and starry Bill Cosby. It was a seriously unfunny film, according to reviews. Some scenes MAY have been shot in Idaho.

1991, Talent for the Game, starring Edward James Olmos and Lorraine Bracco, used Genesee as its backdrop, with some scenes shot in Kellogg. It went quickly to video.

1992, Dark Horse , starring Ed Begley Jr, Samantha Eggar, Ari Meyers, Mimi Rogers, and Tab Hunter. Hunter wrote the original story. David Hemmings directed the film, which was shot not far from his home in Sun Valley.

1992, Toys , starring Robin Williams, Michael Gambon, Joan Cusack, Robin Wright, and LL Cool J. Directed by Barry Levinson, much of it was filmed in and around Moscow. Levinson was nominated for a Razzie for the film. Un, not an honor.

1997, Dante’s Peak , starring Pierce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton. Wallace became a town covered in ash for this (putting on my reviewer hat, now) ridiculous movie. It did well financially in spite of mostly negative reviews.

1998, Smoke Signals , starring Irene Bedard, Adam Bent, and Evan Adams. Shot on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation around Worley and Plummer and based on a short story by Sherman Alexie. It was an all native production that won numerous awards.

1998, Breakfast of Champions, starring Bruce Willis, Albert Finney, Nick Nolte, Barbara Hershey, and Lucas Haas. Based loosely on the Kurt Vonnegut novel of the same name it was shot in and around Twin Falls. It was a box office bomb that was widely panned by critics.

1999, Wild Wild West, starring Will Smith and Kevin Kline. This steampunk western comedy was loosely a take-off from the 1960s TV series of the same name. Some of the train exteriors were filmed on the old Camas Prairie Railroad, which has an abundance of dramatic trestles.

2001, Town and Country , starring Warren Beatty, Diane Keaton, Goldie Hawn, Gary Shandling, Andie MacDowell, Nastassja Kinski, and Charlton Heston. In spite of its stellar cast and a rewrite by Buck Henry, this one was a legendary flop, costing more than $100 million to make and bringing in just over $10 million. It was shot partially in Sun Valley.

2003, Shredder , starring Scott Weinger and Lindsey McKeon was a slasher film sohot at Silver Mounta Ski Resort, Kellogg.

2004, Napoleon Dynamite , starring Jon Heder, Efren Ramirez, Aaron Ruell, Jon Gries, and Sandy Martin. Shot on a budget of about $400,000, this collaboration between BYU film students using mostly friends as actors earned about $45 million. Written by Preston natives Jared and Jerusha Hess, and directed by Jared, it remains a cult classic.

2012, The Mooring , starring Hallie Todd, and others. This was a straight to DVD movie that was shot in Northern Idaho and Eastern Washington. Lake Coeur d’Alene, Chatcolet Lake, and the St. Joe show up in the film, along with camping scenes from Rocky Point and Plummer point in Heyburn State Park.

And, what have I missed? Do you know of some scenes that were shot in Idaho, or maybe an entire movie? Send me details or comment.

I Met Him in Paris would seem to be all about Paris. It was shot largely in Sun Valley.

I Met Him in Paris would seem to be all about Paris. It was shot largely in Sun Valley.

Published on March 11, 2020 04:00

March 10, 2020

A Rocky Start for a Rocky Park

Several parks have come and gone over the 109-year history of state parks in Idaho. One you might remember is Indian Rocks State Park. The Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation (technically the Idaho Department of Parks at the time) acquired 3,000 acres south of Pocatello from the US Bureau of Land Management in 1968 through the Federal Recreation and Public Purposes Act for $2.50 an acre. The Indian Rocks State Park visitor center was located on the west side of I-15 at the exit to Lava Hot Springs.

Park planners hoped campers would stop on their way to Yellowstone National Park. They also hoped a planned reservoir nearby would attract boaters and fishermen. The US Army Corps of Engineers decided there was not enough public support for building a reservoir on nearby Marsh Creek, so that never happened and the boaters never came. The park closed in 1983 during a state budget crisis, and it never reopened.

#indianrocksstatepark #idahostateparkshistory

Park planners hoped campers would stop on their way to Yellowstone National Park. They also hoped a planned reservoir nearby would attract boaters and fishermen. The US Army Corps of Engineers decided there was not enough public support for building a reservoir on nearby Marsh Creek, so that never happened and the boaters never came. The park closed in 1983 during a state budget crisis, and it never reopened.

#indianrocksstatepark #idahostateparkshistory

Published on March 10, 2020 04:00

March 9, 2020

Boise's Reluctant Mayors

There is a strong element today in Idaho’s citizenry that believes there should be as little government as possible. That isn’t a recent development.

The City of Boise was platted on July 7, 1863. It became the capital of Idaho Territory on December 24, 1864. But there was a little problem. Boise had not formed a city government. The Idaho Territorial Legislature believed strongly that the capital should have a few essential things, such as a mayor. The citizens of Boise liked things just the way they were. That is, there were no city ordinances and above all there were no taxes levied on the citizens of the community.

To prod things along, the Legislature incorporated the city. All citizens had to do was approve the charter and elect some officials. That election took place on March 25, 1865. The charter failed by 24 votes.

Inexplicably many of the opponents of the charter lived outside the boundaries that the charter described. It wasn’t strange that they would be opposed. It was strange that they were allowed to vote.

Nevertheless, the Legislature tried again. This time legislators got around those pesky voters by simply passing the charter without requiring a vote of the citizens (or the non-citizens). That bill passed on January 11, 1866, providing a charter that the city would use for the next 95 years.

But there was still the matter of electing city officials, who would organize under the charter they would ultimately approve. The voters got a chance to select their leaders on May 7, 1866. Which they did. Voters elected a mayor and city council, all of whom had pledged not to serve and not to organize a city government. So there.

The Legislature was adamant about the need for some local elected officials, so they set another election for January 11, 1867. Things were looking up for that one. There were two slates of candidates seeking office. Both slates were comprised of men who actually wanted to be mayor or a city councilor. At the last minute an anti-charter party popped up. The slate of no-government candidates ran away with the election, winning 277 to 133. True to their word, all those elected refused to serve.

Things were getting sticky for property owners by this time. Surveys were underway all over the territory. Defining the boundaries of property was a necessary legal step. Without a government in place there was no way to obtain title to property in Boise without an approved charter. An election was held giving the citizens a chance to approve the charter, since they hadn’t elected anyone to do it for them.

In November of 1867, the citizens of Boise finally approved their charter. The fact that the mayor and councilors they had elected refused to serve was problematic. H.E. Prickett, who would later serve on the territorial supreme court, stepped up to serve as mayor when the elected mayor, L.B. Lindsey kept his promise not to take office. Most of those elected to the council grudgingly agreed to serve and begin organizing the city. Ordinances, taxes, and government services followed in their wake.

Most other cities in the state were organized under general provisions laid out by the legislature. Since Boiseans refused to do so and ended up having a charter thrust upon them, it was uniquely hamstrung. The city couldn’t grow beyond its borders because it didn’t have the authority to annex adjacent property.

It did not go unnoticed by city officials in the late 1950s that the capital of Idaho was soon to be eclipsed in population. The population of Boise in the 1950 census was 34,393. In 1960 it was 34,481. That was a growth rate of .03 percent. The population of Idaho Falls, Idaho’s second largest city at the time, was 33,161 in 1960. It was likely that Idaho Falls or Pocatello—both with the ability to annex—would surpass Idaho’s capital city when the 1970 census was tallied.

The solution to the annexation problem was simple. Dissolve the charter. If the 1866 charter put in place by the legislature were abolished, Boise could operate under the general rules of most cities in Idaho.

In 1961 the Idaho Legislature abolished Boise’s 1866 charter, freeing the city to grow.

The original recalcitrance of the citizens of Boise in the 1860s gave the city some unusual history. It’s first elected mayor was Dr. Ephraim Smith. He refused to serve in that capacity, but his photo hangs in Boise City Hall as the first mayor chosen by the people. His election was completely forgotten by city officials until his son sent them Smith’s certificate of election in 1936.

The first mayor who served, Henry E. Prickett, was appointed rather than elected. Two adamant opponents of the creation of a city charter Peter Sonna and James A. Pinney eventually dropped their opposition, apparently. Both would later serve as mayors of Boise.

Dr. Ephraim Smith was the first elected mayor of Boise. He ran on the platform that he would refuse to serve if elected. He kept that promise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-3.

Dr. Ephraim Smith was the first elected mayor of Boise. He ran on the platform that he would refuse to serve if elected. He kept that promise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-3.  Henry E. Prickett was the man who first served as Boise’s mayor. He wasn’t elected. Prickett was appointed by the city council. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-9.

Henry E. Prickett was the man who first served as Boise’s mayor. He wasn’t elected. Prickett was appointed by the city council. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-9.

The City of Boise was platted on July 7, 1863. It became the capital of Idaho Territory on December 24, 1864. But there was a little problem. Boise had not formed a city government. The Idaho Territorial Legislature believed strongly that the capital should have a few essential things, such as a mayor. The citizens of Boise liked things just the way they were. That is, there were no city ordinances and above all there were no taxes levied on the citizens of the community.

To prod things along, the Legislature incorporated the city. All citizens had to do was approve the charter and elect some officials. That election took place on March 25, 1865. The charter failed by 24 votes.

Inexplicably many of the opponents of the charter lived outside the boundaries that the charter described. It wasn’t strange that they would be opposed. It was strange that they were allowed to vote.

Nevertheless, the Legislature tried again. This time legislators got around those pesky voters by simply passing the charter without requiring a vote of the citizens (or the non-citizens). That bill passed on January 11, 1866, providing a charter that the city would use for the next 95 years.

But there was still the matter of electing city officials, who would organize under the charter they would ultimately approve. The voters got a chance to select their leaders on May 7, 1866. Which they did. Voters elected a mayor and city council, all of whom had pledged not to serve and not to organize a city government. So there.

The Legislature was adamant about the need for some local elected officials, so they set another election for January 11, 1867. Things were looking up for that one. There were two slates of candidates seeking office. Both slates were comprised of men who actually wanted to be mayor or a city councilor. At the last minute an anti-charter party popped up. The slate of no-government candidates ran away with the election, winning 277 to 133. True to their word, all those elected refused to serve.

Things were getting sticky for property owners by this time. Surveys were underway all over the territory. Defining the boundaries of property was a necessary legal step. Without a government in place there was no way to obtain title to property in Boise without an approved charter. An election was held giving the citizens a chance to approve the charter, since they hadn’t elected anyone to do it for them.

In November of 1867, the citizens of Boise finally approved their charter. The fact that the mayor and councilors they had elected refused to serve was problematic. H.E. Prickett, who would later serve on the territorial supreme court, stepped up to serve as mayor when the elected mayor, L.B. Lindsey kept his promise not to take office. Most of those elected to the council grudgingly agreed to serve and begin organizing the city. Ordinances, taxes, and government services followed in their wake.

Most other cities in the state were organized under general provisions laid out by the legislature. Since Boiseans refused to do so and ended up having a charter thrust upon them, it was uniquely hamstrung. The city couldn’t grow beyond its borders because it didn’t have the authority to annex adjacent property.

It did not go unnoticed by city officials in the late 1950s that the capital of Idaho was soon to be eclipsed in population. The population of Boise in the 1950 census was 34,393. In 1960 it was 34,481. That was a growth rate of .03 percent. The population of Idaho Falls, Idaho’s second largest city at the time, was 33,161 in 1960. It was likely that Idaho Falls or Pocatello—both with the ability to annex—would surpass Idaho’s capital city when the 1970 census was tallied.

The solution to the annexation problem was simple. Dissolve the charter. If the 1866 charter put in place by the legislature were abolished, Boise could operate under the general rules of most cities in Idaho.

In 1961 the Idaho Legislature abolished Boise’s 1866 charter, freeing the city to grow.

The original recalcitrance of the citizens of Boise in the 1860s gave the city some unusual history. It’s first elected mayor was Dr. Ephraim Smith. He refused to serve in that capacity, but his photo hangs in Boise City Hall as the first mayor chosen by the people. His election was completely forgotten by city officials until his son sent them Smith’s certificate of election in 1936.

The first mayor who served, Henry E. Prickett, was appointed rather than elected. Two adamant opponents of the creation of a city charter Peter Sonna and James A. Pinney eventually dropped their opposition, apparently. Both would later serve as mayors of Boise.

Dr. Ephraim Smith was the first elected mayor of Boise. He ran on the platform that he would refuse to serve if elected. He kept that promise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-3.

Dr. Ephraim Smith was the first elected mayor of Boise. He ran on the platform that he would refuse to serve if elected. He kept that promise. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-3.  Henry E. Prickett was the man who first served as Boise’s mayor. He wasn’t elected. Prickett was appointed by the city council. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-9.

Henry E. Prickett was the man who first served as Boise’s mayor. He wasn’t elected. Prickett was appointed by the city council. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 250-9.

Published on March 09, 2020 04:00

March 8, 2020

Firth

How do you go about getting a town named after you? Well, you could set out to be a beloved politician (good luck), or a war hero. That might get you a town or two. Or, you could just donate the land to get the town started.

That was how Lorenzo Firth did it, though having a town named after him probably wasn’t his goal. He was a homesteader who had come over from Wakefield, England as young boy. He liked to tell the story about how he and a friend about his age were captured by Indians, who tied them to wild ponies and poked and prodded the horses to make them run and buck. The boys thought they were going to be killed, but the Indians turned them loose after they’d had their fun.

Firth worked on a ranch near Rock Springs (now Wyoming). It was there that he met and became friends with noted mountain man Jim Bridger.

Firth married Dorcas Martin in 1873 in Uinta, Utah Territory. They moved to Basalt, Idaho Territory in 1887. It was there that he homesteaded, with their land bisected by railroad tracks. The Oregon Shortline Railroad built a small depot near the Firth place and people began to call the stop Firth. When Lorenzo donated land for a school and town site, that sealed the deal. In 1905 the fledgling community was dedicated as Firth.

Pictured is the Lorenzo Firth homestead in 1894. Left to right in front are daughter Mabel Firth, son Thomas on the rocking horse, Marion Firth in the arms of her mother Dorcas, Lorenzo Firth, and his daughter Emma. Holding the horse team are Nels Fred Nelson and Mary Ann Firth Nelson. In the spring wagon is “Auntie Karr and daughter and person unknown.” The photo is courtesy of Marlene Reid from the book she and husband Wallace edited to celebrate Firth’s centennial in 2005.

That was how Lorenzo Firth did it, though having a town named after him probably wasn’t his goal. He was a homesteader who had come over from Wakefield, England as young boy. He liked to tell the story about how he and a friend about his age were captured by Indians, who tied them to wild ponies and poked and prodded the horses to make them run and buck. The boys thought they were going to be killed, but the Indians turned them loose after they’d had their fun.

Firth worked on a ranch near Rock Springs (now Wyoming). It was there that he met and became friends with noted mountain man Jim Bridger.

Firth married Dorcas Martin in 1873 in Uinta, Utah Territory. They moved to Basalt, Idaho Territory in 1887. It was there that he homesteaded, with their land bisected by railroad tracks. The Oregon Shortline Railroad built a small depot near the Firth place and people began to call the stop Firth. When Lorenzo donated land for a school and town site, that sealed the deal. In 1905 the fledgling community was dedicated as Firth.

Pictured is the Lorenzo Firth homestead in 1894. Left to right in front are daughter Mabel Firth, son Thomas on the rocking horse, Marion Firth in the arms of her mother Dorcas, Lorenzo Firth, and his daughter Emma. Holding the horse team are Nels Fred Nelson and Mary Ann Firth Nelson. In the spring wagon is “Auntie Karr and daughter and person unknown.” The photo is courtesy of Marlene Reid from the book she and husband Wallace edited to celebrate Firth’s centennial in 2005.

Published on March 08, 2020 05:00

March 7, 2020

Idaho's Border Graves

It’s well-known that Idaho’s first permanent settlement, the town of Franklin, was settled by pioneers who thought they were still in Utah. They discovered their mistake only after a survey placed the border a bit south of them. Welcome to Idaho!

One of those Welcome to Idaho signs is on I-15 on the border south of Malad. Just up the hill from that sign, on the Idaho side of the border, are two graves, each with a grave-sized fence around it. Neither of the occupants of the graves were from Franklin, but one could be forgiven for wondering. The dying wish for both was to be buried in Utah. Oops.

Hugh Moon was the first to find himself permanently located on the wrong side of the border. Mr. Moon was born in England in 1815. In 1840 he joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and sailed to the United States. He was a devout Mormon who at one time served as a bodyguard for Joseph Smith. Keep that tidbit of trivia in mind.

He married in 1848 in Utah. Brigham Young had him move to Dixie in southern Utah to strengthen the church community there. Later he and his family moved to Henderson Creek in Idaho Territory. It was there that he died. He considered Utah to be Zion, and he wanted to be buried there. His family, doing their best to honor his wishes chose a gravesite on a hillside overlooking Cherry Creek south of Malad. The border survey would come later.

Hugh Moon wasn’t the only one who wanted to be buried in Utah. Jane Copeland Howell, born in Illinois in 1789, became a resident of Idaho Territory in 1868. She had moved there with her son and his family. They had lived in Kaysville, Utah for five years previously. Jane Howell had some affinity for Utah, though she wasn’t LDS. She begged her family to see that she was buried there, not in Idaho, where she had lived for only a short time. They did their best, locating her gravesite near that of Hugh Moon, probably assuming Moon’s relatives knew what they were doing. Again, the border survey proved them wrong.

There is something of an urban legend attached to the graves. As is often the case with such things, there is a nubbin of truth to the story. The legend has it that the two graves belonged to bodyguards of Brigham Young, who inexplicably hated Utah so much that they asked to be buried in Idaho. The truth nubbin was that Hugh Moon was the bodyguard of a church leader, Joseph Smith.

If there’s a moral to this story, it’s probably one that would rarely be useful today: Make sure the survey is complete before you commit to eternity in Utah.

Thanks to Monte Layton who first passed on this story to me.

One of those Welcome to Idaho signs is on I-15 on the border south of Malad. Just up the hill from that sign, on the Idaho side of the border, are two graves, each with a grave-sized fence around it. Neither of the occupants of the graves were from Franklin, but one could be forgiven for wondering. The dying wish for both was to be buried in Utah. Oops.

Hugh Moon was the first to find himself permanently located on the wrong side of the border. Mr. Moon was born in England in 1815. In 1840 he joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and sailed to the United States. He was a devout Mormon who at one time served as a bodyguard for Joseph Smith. Keep that tidbit of trivia in mind.

He married in 1848 in Utah. Brigham Young had him move to Dixie in southern Utah to strengthen the church community there. Later he and his family moved to Henderson Creek in Idaho Territory. It was there that he died. He considered Utah to be Zion, and he wanted to be buried there. His family, doing their best to honor his wishes chose a gravesite on a hillside overlooking Cherry Creek south of Malad. The border survey would come later.

Hugh Moon wasn’t the only one who wanted to be buried in Utah. Jane Copeland Howell, born in Illinois in 1789, became a resident of Idaho Territory in 1868. She had moved there with her son and his family. They had lived in Kaysville, Utah for five years previously. Jane Howell had some affinity for Utah, though she wasn’t LDS. She begged her family to see that she was buried there, not in Idaho, where she had lived for only a short time. They did their best, locating her gravesite near that of Hugh Moon, probably assuming Moon’s relatives knew what they were doing. Again, the border survey proved them wrong.

There is something of an urban legend attached to the graves. As is often the case with such things, there is a nubbin of truth to the story. The legend has it that the two graves belonged to bodyguards of Brigham Young, who inexplicably hated Utah so much that they asked to be buried in Idaho. The truth nubbin was that Hugh Moon was the bodyguard of a church leader, Joseph Smith.

If there’s a moral to this story, it’s probably one that would rarely be useful today: Make sure the survey is complete before you commit to eternity in Utah.

Thanks to Monte Layton who first passed on this story to me.

Published on March 07, 2020 04:00

March 6, 2020

Bridges Gone Bad

The Idaho Transportation Department has released thousands of digitized photos from their files for the public’s enjoyment. Here's a little series I call Bridges Gone Bad.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today.

This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed.

This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed.

Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?

Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today. This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed.

This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed. Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?

Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?

Published on March 06, 2020 04:00