Rick Just's Blog, page 164

April 24, 2020

Puny Plates

This rates more as nostalgia than history, but I thought I’d share it. Back in the 1950s and 60s the Disabled American Veterans used to send out key tags as a fundraiser. They hoped that you would be so pleased with the tags that looked just like your license plate that you’d send them a little money. I think you could drop them in a mailbox, and they would eventually find their way back to you.

But I was a kid. I didn’t have a car until 1968, so it was the license tag itself that fascinated me. They were just the right size to put on the front and back of a Tonka toy truck, if you could talk your parents out of them. And if you could figure out a way to mount them.

This particular set was among my grandfather’s possessions that we sifted through years ago. This was apparently his license number in 1953. He was a notoriously bad driver, so it’s a bit of miracle that he had a car he could put tags on.

By the way, it would be much more difficult to pull this off today. The Idaho Transportation Department isn’t keen on providing lists of names associated with license plates. It’s a privacy issue.

But I was a kid. I didn’t have a car until 1968, so it was the license tag itself that fascinated me. They were just the right size to put on the front and back of a Tonka toy truck, if you could talk your parents out of them. And if you could figure out a way to mount them.

This particular set was among my grandfather’s possessions that we sifted through years ago. This was apparently his license number in 1953. He was a notoriously bad driver, so it’s a bit of miracle that he had a car he could put tags on.

By the way, it would be much more difficult to pull this off today. The Idaho Transportation Department isn’t keen on providing lists of names associated with license plates. It’s a privacy issue.

Published on April 24, 2020 04:00

April 23, 2020

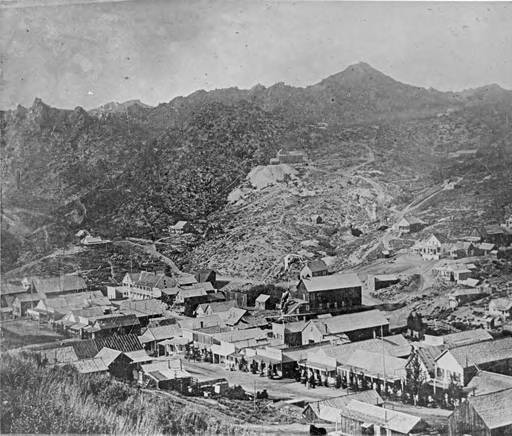

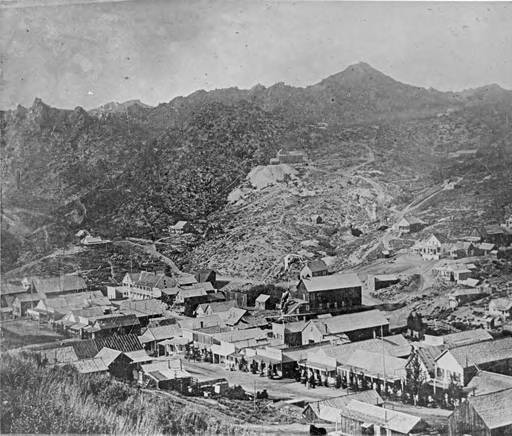

Silver City Theater

What turns a group of buildings thrown up to provide essentials for miners into a community? In the 1860s Silver City had billiard halls, horse races, saloons, gambling halls, a red-light district, and a fledgling library. But what it really needed, according the Owyhee Avalanche was a theater. The May 5, 1866 edition of the newspaper carried an editorial that said in part, “Parties who have the cash to spare could hardly use it to more certain advantages than in erecting a theater building of neat finish and reasonable dimensions. In the dullest times, theatrical and minstrel performances are well patronized. We verily believe that if one could be put in operation now with fair talent and creditable management, it would be crowded nightly.”

By 1868, Silver City must have been a fine community, indeed, because it had TWO theaters. John McGinely, one of the theater owners, promoted an early production by offering to give a gold ring worth $10 to the person in the audience who could come up with the most original conundrum (a riddle whose answer is a pun). Sadly, the winning riddle did not survive the ages.

The newspaper whose editorial plea may have sparked theater in Silver City, was not always a fan of the productions. On May 21, 1870, the paper gave one troupe a slap:

“The Carter Troupe have ‘folded their tents like the Arabs and silently stole away.’ Good riddance. Although his playing was passable, yet we couldn’t tolerate so much beggarly meanness as was concentrated in the person of J.W. Carter. We gave him a complementary notice last week which he didn’t seem to appreciate. Of all the contemptible catchpennies that ever afflicted our Territory he is the chief; of all the miserly exotics that ever visited Idaho he is conspicuous; of all the pitiful paltry scrubs that we ever saw, he caps the climax.”

Some productions had moved to Champion Hall by 1873, a new theater facility with seating for perhaps 150. On opening night the audience got a little scare when one of the supports for the building settled loudly and abruptly. It may have been an ominous sign. Silver City was attracting fewer professional productions and many of the amateurs who had performed had moved away. By 1874 the Owyhee Avalanche reported that “The old Silver City Theatre was torn down and moved to the Mahogany mine this week, where it will be rebuilt for an engine-house, etc.”

Things happened fast in a boom town. For the most part, the heyday of theater came and went in a period of about six years in Silver City. Not very long, but long enough for the newspaper to think of one of the theaters as “old.”

The photo of Silver City in 1891 is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

By 1868, Silver City must have been a fine community, indeed, because it had TWO theaters. John McGinely, one of the theater owners, promoted an early production by offering to give a gold ring worth $10 to the person in the audience who could come up with the most original conundrum (a riddle whose answer is a pun). Sadly, the winning riddle did not survive the ages.

The newspaper whose editorial plea may have sparked theater in Silver City, was not always a fan of the productions. On May 21, 1870, the paper gave one troupe a slap:

“The Carter Troupe have ‘folded their tents like the Arabs and silently stole away.’ Good riddance. Although his playing was passable, yet we couldn’t tolerate so much beggarly meanness as was concentrated in the person of J.W. Carter. We gave him a complementary notice last week which he didn’t seem to appreciate. Of all the contemptible catchpennies that ever afflicted our Territory he is the chief; of all the miserly exotics that ever visited Idaho he is conspicuous; of all the pitiful paltry scrubs that we ever saw, he caps the climax.”

Some productions had moved to Champion Hall by 1873, a new theater facility with seating for perhaps 150. On opening night the audience got a little scare when one of the supports for the building settled loudly and abruptly. It may have been an ominous sign. Silver City was attracting fewer professional productions and many of the amateurs who had performed had moved away. By 1874 the Owyhee Avalanche reported that “The old Silver City Theatre was torn down and moved to the Mahogany mine this week, where it will be rebuilt for an engine-house, etc.”

Things happened fast in a boom town. For the most part, the heyday of theater came and went in a period of about six years in Silver City. Not very long, but long enough for the newspaper to think of one of the theaters as “old.”

The photo of Silver City in 1891 is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on April 23, 2020 04:00

April 22, 2020

Paid Parking in Murphy

How small is it? That sounds like a joke set-up, rather than the beginning of a totally serious story about Murphy, Idaho and its famous parking meter.

In January, 1956, the Associated Press fed a story to their wire service subscribers about Murphy, Idaho’s solitary parking meter. Murphy had only 31 residents, which probably made it the county seat with the smallest population in the country. Since then, the population has skyrocketed to nearly 100 people.

But about that parking meter… Kenneth Downing, then the county clerk, thought it might be a good gag to install a parking meter in front of a wire gate at the courthouse that people were always blocking with their cars. It seemed to cut down on the pesky parking, but it didn’t raise a lot of money. It didn’t even work, at first. City fathers, or city jokesters, or someone later repaired it so they could collect coins. Theoretically.

Downing appeared in the AP photo that accompanied the story tying his horse up to the meter. The article pointed out that there were probably more horses in the county than cars, anyway.

You can still visit Owyhee County’s only parking meter today, more than 50 years later, making this one long-running joke.

In January, 1956, the Associated Press fed a story to their wire service subscribers about Murphy, Idaho’s solitary parking meter. Murphy had only 31 residents, which probably made it the county seat with the smallest population in the country. Since then, the population has skyrocketed to nearly 100 people.

But about that parking meter… Kenneth Downing, then the county clerk, thought it might be a good gag to install a parking meter in front of a wire gate at the courthouse that people were always blocking with their cars. It seemed to cut down on the pesky parking, but it didn’t raise a lot of money. It didn’t even work, at first. City fathers, or city jokesters, or someone later repaired it so they could collect coins. Theoretically.

Downing appeared in the AP photo that accompanied the story tying his horse up to the meter. The article pointed out that there were probably more horses in the county than cars, anyway.

You can still visit Owyhee County’s only parking meter today, more than 50 years later, making this one long-running joke.

Published on April 22, 2020 04:00

April 21, 2020

Dredging the Yankee Fork

The Yankee Fork Dredge is probably the best-preserved machine of its kind in the lower 48. Built in 1940 by Bucyrus Erie, the machine was designed to pull out the $11 million worth of gold that allegedly sat there for the taking in the gravel bed along a 5 ½ mile stretch of Yankee Fork Creek just before it flows into the Salmon River.

The Silas Mason Company of New York assembled the dredge on site mostly from parts hauled in by train to Mackay, then by truck to the claim. The pontoons that let the dredge float were manufactured in Boise, as was the superstructure.

The dredge weighs 988 tons, and is 112 feet long by 54 feet wide by 64 feet high. Each of the 71 buckets that make up the mouth of the digging chain can hold 8 cubic feet and themselves weigh a little over a ton. Imagine a chain saw with iron buckets linked together instead of a chain. That’s what bit into the creek bottom relentlessly driven by twin 350 hp diesel engines. The gravel fed into a conveyor system inside the dredge where the gold was sifted out. A swinging arm behind the machine spit out gravel in neat arcs producing rock hills in its wake, the ridges of which look like the backbone of a buried dragon.

The dredge worked the claim off and on until 1952. The J.R. Simplot Company bought the operation in 1949.

The dredge didn’t find $11 million in gold, only about $1.5 million. It cost about that to operate, so turning the creek upside down didn’t pay much of a dividend.

Still, the dredge is an interesting place to visit. Regular tours are conducted Memorial Day Weekend through Labor Day. Google it for details.

The Forest Service is planning some ambitious restoration work in the valley, which is the best news the stream has had since 1952.

The photo of the dredge is courtesy of Mario Delisio.

The Silas Mason Company of New York assembled the dredge on site mostly from parts hauled in by train to Mackay, then by truck to the claim. The pontoons that let the dredge float were manufactured in Boise, as was the superstructure.

The dredge weighs 988 tons, and is 112 feet long by 54 feet wide by 64 feet high. Each of the 71 buckets that make up the mouth of the digging chain can hold 8 cubic feet and themselves weigh a little over a ton. Imagine a chain saw with iron buckets linked together instead of a chain. That’s what bit into the creek bottom relentlessly driven by twin 350 hp diesel engines. The gravel fed into a conveyor system inside the dredge where the gold was sifted out. A swinging arm behind the machine spit out gravel in neat arcs producing rock hills in its wake, the ridges of which look like the backbone of a buried dragon.

The dredge worked the claim off and on until 1952. The J.R. Simplot Company bought the operation in 1949.

The dredge didn’t find $11 million in gold, only about $1.5 million. It cost about that to operate, so turning the creek upside down didn’t pay much of a dividend.

Still, the dredge is an interesting place to visit. Regular tours are conducted Memorial Day Weekend through Labor Day. Google it for details.

The Forest Service is planning some ambitious restoration work in the valley, which is the best news the stream has had since 1952.

The photo of the dredge is courtesy of Mario Delisio.

Published on April 21, 2020 04:00

April 20, 2020

Buck, Buck, Buck

I’ve been to many places in Idaho and still have a lifetime of it to see. One place I likely won’t visit up close and personal, is the top of Mt. Borah, Idaho’s tallest peak. I’ve given some thought to climbing it. In climbing vernacular, it’s a “walk up.” Tempting. But there’s that one spot that’s scary enough to have its own name. That’s Chicken Out Ridge.

I’ve had many friends climb Borah. They’ve all assured me that there’s nothing to it. Well, except for the one spot that’s a little hairy.

Uh huh. This falls into the same category as those times when my wife tells me, “Try it. It isn’t hot.”

I am not a fan of declivities, and I HAVE seen the pictures, one of which is included with this post so that you can be the judge. This is the ridge running up toward the top, with a well-worn trail beckoning, though it is not a photo of the “hairy” part.

Mount Borah doesn’t look like much from the highway, which has always been my vantage point. From other angles, it looks quite spectacular. It is one of only three peaks in Idaho with more than 5,000 feet of prominence, the other two being He Devil and Diamond Peak.

As a walk-up, it was likely climbed by indigenous peoples many years ago, but the first recorded climb was by a USGS surveyor, T.M. Bannon in 1912. There are more difficult ascents you can take if you’re an experienced climber and the Chicken Out Ridge route seems, uh, pedestrian. Go for it. Send me a postcard.

I’ve had many friends climb Borah. They’ve all assured me that there’s nothing to it. Well, except for the one spot that’s a little hairy.

Uh huh. This falls into the same category as those times when my wife tells me, “Try it. It isn’t hot.”

I am not a fan of declivities, and I HAVE seen the pictures, one of which is included with this post so that you can be the judge. This is the ridge running up toward the top, with a well-worn trail beckoning, though it is not a photo of the “hairy” part.

Mount Borah doesn’t look like much from the highway, which has always been my vantage point. From other angles, it looks quite spectacular. It is one of only three peaks in Idaho with more than 5,000 feet of prominence, the other two being He Devil and Diamond Peak.

As a walk-up, it was likely climbed by indigenous peoples many years ago, but the first recorded climb was by a USGS surveyor, T.M. Bannon in 1912. There are more difficult ascents you can take if you’re an experienced climber and the Chicken Out Ridge route seems, uh, pedestrian. Go for it. Send me a postcard.

Published on April 20, 2020 04:00

April 19, 2020

Idaho's Famous Slaves

Idaho was not involved in the Civil War, though one can find vestiges of that sad chapter of American history in towns and places named by proponents of one side or another. Atlanta and Yankee Fork are two examples.

Idaho was not involved in the Civil War, though one can find vestiges of that sad chapter of American history in towns and places named by proponents of one side or another. Atlanta and Yankee Fork are two examples.But slavery played a part in earliest Idaho history.

Lewis and Clark, those great and fortunate explorers who first came into what would later become Idaho brought slavery with them. William Clark owned an African-American man named York. Clark’s father had given the explorer the man when both were boys.

By all accounts York was treated well on the expedition and seemed to find some measure of freedom there, trusted to reconnoiter on his own. He was also given an equal vote with other members of the Corps of Discovery.

York’s taste of freedom turned bitter when he did not receive pay at the end of the journey, as others did. He asked for his freedom, but Clark at refused to grant it. Accounts are not in agreement about what happened to York in the ensuing years. Clark eventually gave him his freedom, but what York did with it is still unclear. One account has him living out his life as an honored member of the Crow tribe.

York has received some recognition. Wikipedia lists two books about him written by Frank X. Walker. A play and an opera were also written about York. Books about the Corps of Discovery often mention him admiringly. A statue of York (pictured) stands in Louisville, Kentucky.

York deserved better from Clark. But, both were men of their times and to expect Clark to behave differently would be to expect him to transcend his upbringing and the life he was accustomed to living.

I can’t resist adding a footnote to this story of a famous slave. York was not the only member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition who had been enslaved. Definitions can be tricky, but Sacagawea (or Sacajawea, if you prefer) was taken from her family at about age 12 in a battle between her Lemhi Shoshone Tribe and members of the Hidatsa Tribe. She was sold, or claimed as a gambling prize, by Toussaint Charbonneau and became his wife at age 13.

Published on April 19, 2020 04:00

April 18, 2020

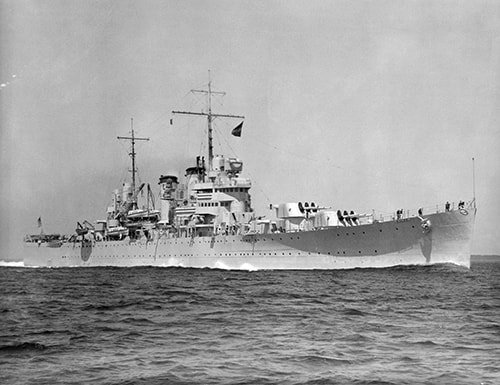

USS Boise

If you’ve paid even passing attention to World War II history, you’re familiar with General Douglas MacArthur’s famous promise after his escape from the Philippines, “I shall return.” What you may have missed is exactly how it was he kept that promise. He went back on his flagship, the U.S.S. Boise.

If you’ve paid even passing attention to World War II history, you’re familiar with General Douglas MacArthur’s famous promise after his escape from the Philippines, “I shall return.” What you may have missed is exactly how it was he kept that promise. He went back on his flagship, the U.S.S. Boise. The Boise, commissioned in 1938, was in the Philippines when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The light cruiser was in the thick of it from the beginning. The ship assisted in the first attack on the island of Japan by sailing around to the south among smaller islands, sending out confusing radio transmissions while Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle’s airmen carried out the Doolittle Raid, also known as the Tokyo Raid.

A few months later the Boise participated in the Battle of Guadalcanal, taking a hit from a Japanese heavy cruiser just minutes into the battle. That cost the U.S. 140 men. But the Boise wasn’t down. She limped to the Philadelphia shipyard for repairs.

In 1943 the U.S.S. Boise found itself in a different theater of war at the Battle of Gela in the invasion of Sicily. She participated in further battles for Sicily and for Italy in August and September 1943.

As the war ended in Europe, the Boise was part of the convoys bringing soldiers back to the United States.

Then, the ship returned to the Philippines in triumph as the flagship for General Douglas MacArthur from June 3-15 during his promised return.

They decommissioned the U.S.S. Boise in 1946 and she was eventually scrapped. Here's a short little clip about the WWII U.S.S. Boise that I thought you might find interesting.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention that there is another U.S.S. Boise sailing today. The Los Angeles-class nuclear attack submarine USS Boise (SSN-764) launched in 1991 and is still in active service.

Published on April 18, 2020 04:00

April 17, 2020

The Undisputed (?) Center of the Universe

Wallace, Idaho is a quirky little town that you need to visit, if you haven’t done so. Quirky? Visit the Oasis Bordello Museum if you’re not convinced of its quirkiness. Or check out the stoplight in a coffin.

For years Wallace had the only stoplight on Interstate 90 anywhere along its 3,100-mile coast-to-coast length. A bypass took care of that little issue in 1991. The town held a funeral for the stoplight, complete with a horse-drawn hearse and solemn bagpipes. It now rests in its casket at the Wallace Mining Museum.

We’ve already got two museums in this story, so let’s round it out with one more. The Northern Pacific Railroad Museum is in the beautiful brick building that once served as the town’s railroad depot.

Wallace is proud to claim movie star Lana Turner as one of its own. And the town itself starred in a movie, once. Dante’s Peak, a 1997 film featuring Peirce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton, asked you to really, really suspend your disbelief for an hour and 48 minutes. It was shot in and around Wallace.

Wallace wasn’t always Wallace. It started out as an area called Cedar Swamp, because it was located in a swamp. With cedars all around it. Then, in 1884, it became Placer Center because of all the placer mining going on. When it finally incorporated, they named the town after Colonel W. R. Wallace, the owner of much of the town property and a member of the first city council. Not so quirky, that.

But, there’s the whole “Center of the Universe” thing. In 2004, the mayor gave a proclamation that read in part:

“I, Ron Garitone, Mayor of Wallace, Idaho, and all of its subjects, and being of sound body and mind, do hereby solemnly declare and proclaim Wallace to be the Center of the Universe.

“Thanks to the newly discovered science of 'Probalism' - specifically probalistic modeling, pioneered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Health and Welfare, and peer-reviewed by La Cosa Nostra and the Flat Earth Society - we were further able to pinpoint the exact center within the Center of the Universe; to wit: a sewer access cover slightly off-center from the intersection of Bank and Sixth Streets.

“Upon discovering this desecration of the Center of the Universe, we proceeded forthwith to remove said manhole cover and replace it with this fine Monument, directing all who come upon it to the Four Corners of the Universe, these being the Bunker Hill, the Sunshine, the Lucky Friday and the Galena Mines.”

The photo of the manhole cover certainly proves that Wallace, center of the universe or not, is certifiably quirky.

For years Wallace had the only stoplight on Interstate 90 anywhere along its 3,100-mile coast-to-coast length. A bypass took care of that little issue in 1991. The town held a funeral for the stoplight, complete with a horse-drawn hearse and solemn bagpipes. It now rests in its casket at the Wallace Mining Museum.

We’ve already got two museums in this story, so let’s round it out with one more. The Northern Pacific Railroad Museum is in the beautiful brick building that once served as the town’s railroad depot.

Wallace is proud to claim movie star Lana Turner as one of its own. And the town itself starred in a movie, once. Dante’s Peak, a 1997 film featuring Peirce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton, asked you to really, really suspend your disbelief for an hour and 48 minutes. It was shot in and around Wallace.

Wallace wasn’t always Wallace. It started out as an area called Cedar Swamp, because it was located in a swamp. With cedars all around it. Then, in 1884, it became Placer Center because of all the placer mining going on. When it finally incorporated, they named the town after Colonel W. R. Wallace, the owner of much of the town property and a member of the first city council. Not so quirky, that.

But, there’s the whole “Center of the Universe” thing. In 2004, the mayor gave a proclamation that read in part:

“I, Ron Garitone, Mayor of Wallace, Idaho, and all of its subjects, and being of sound body and mind, do hereby solemnly declare and proclaim Wallace to be the Center of the Universe.

“Thanks to the newly discovered science of 'Probalism' - specifically probalistic modeling, pioneered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Health and Welfare, and peer-reviewed by La Cosa Nostra and the Flat Earth Society - we were further able to pinpoint the exact center within the Center of the Universe; to wit: a sewer access cover slightly off-center from the intersection of Bank and Sixth Streets.

“Upon discovering this desecration of the Center of the Universe, we proceeded forthwith to remove said manhole cover and replace it with this fine Monument, directing all who come upon it to the Four Corners of the Universe, these being the Bunker Hill, the Sunshine, the Lucky Friday and the Galena Mines.”

The photo of the manhole cover certainly proves that Wallace, center of the universe or not, is certifiably quirky.

Published on April 17, 2020 04:00

April 16, 2020

Mining Silver and Hot Water

Robert Currie Beardsley, courtesy of Challis Hot Springs. Robert Currie Beardsley, born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1840, had tried his luck at running a sawmill in Montana and mining in California, but he didn’t make a real go of it until he moved to Idaho in 1877. He and two partners, W. A. Norton and J.B. Hood discovered what would become the Beardsley Mine near Bayhorse. The town was so named because an earlier miner who had a couple of bay horses first told of of riches along what would soon become Bayhorse Creek, about 14 miles southwest of Challis.

Robert Currie Beardsley, courtesy of Challis Hot Springs. Robert Currie Beardsley, born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1840, had tried his luck at running a sawmill in Montana and mining in California, but he didn’t make a real go of it until he moved to Idaho in 1877. He and two partners, W. A. Norton and J.B. Hood discovered what would become the Beardsley Mine near Bayhorse. The town was so named because an earlier miner who had a couple of bay horses first told of of riches along what would soon become Bayhorse Creek, about 14 miles southwest of Challis.The Beardsley Mine, once said to be the second largest silver mine in the state, was one of two major operations at Bayhorse. The other was the Ramshorn Mine.

After operating his mine for several years, Robert Beardsley sold his share in the mine for $40,000, setting him up for life. Sadly, it was a short life.

In 1884, Beardsley travelled to New Orleans for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. It was one of the first major world expositions. Think of it as a world’s fair. Beardsley probably did not go seeking a wife. Nevertheless, he found one.

The New Orleans Times-Democrat reported that on the 18th of February 1886, “another link was forged in the chain that binds Louisiana to the far Northwest. It was a golden link, and took the shape of a marriage between Robert Beardsley, one of the representative men of Idaho Territory—a hard-headed, successful miner—and Miss (Eleanor) Nellie Hallaran, of Magazine street, a native of this city. Mr. Beardsley met the lady last year while here on a visit to the Exposition. He said nothing but bore away in his Northwestern heart so strong an impress of her image that his return was a matter of necessity.” The newlyweds left the next day, taking a train to Blackfoot, then travelling by stage to Challis.

Though his name is attached to his mine in the history books, Beardsley left a legacy that far outlasted it. He homesteaded on a property east of Challis in 1880. The view was gorgeous and the meadows green, but it was the water that attracted Beardsley. It was hot. So hot that horse teams pulling Fresno scrapers to dig the soaking pools had to be changed out every couple of hours to let their hooves cool down.

Known today as Challis Hot Springs, the place was originally the Beardsley Resort and Hotel. Robert Beardsley floated logs down the Salmon from forested hillsides upriver and pulled them out on his property to construct some early buildings. Perhaps this casual, friendly relationship with the river gave him a false sense of confidence.

On June 30, 1888, Beardsley set out to cross the river to his hot springs resort with a team of horses and a wagon. While a handful of people watched, the raging current caught and tumbled the wagon, pulling the team and Beardsley under. Beardsley was sighted for a time in the current, but there was no way to attempt a rescue. You can find his grave on the mountainside above the hot springs today.

Eleanor eventually remarried a man named John Kirk. Eleanor continued to build up the hot springs resort. Ownership eventually passed to Eleanor and Robert Beardsley’s daughter Isabella and her husband John Hammond in 1931. Their son Robert Beardsley Hammond took over the hot springs in 1951. Twenty years later, his son, Robert Charles Hammond, purchased Challis Hot Springs. Bob and his wife Lorna maintained a home on the property until November 2013, when Bob passed away. Their two daughters, Kate Taylor and Mary Elizabeth Conner, manage the now fifth-generation facility today.

Published on April 16, 2020 04:00

April 15, 2020

Idaho's Floating Town

Named for Teddy Roosevelt, the mining town of Roosevelt, Idaho is a footnote in Idaho’s history of disasters. The ramshackle town, east of Yellowpine, started in 1902 when miners first came to the Thunder Mountain District on rumors of a major gold find. The Dewey Mine’s production fell far short of the rumors. It operated for five years, closing in 1907.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

A few obstinate miners hung on, but Roosevelt was all but a ghost town in the spring of 1909 when “disaster” struck. It was the slow-moving kind of disaster that occurred without human casualty. A landslide three miles long and 200 feet high plugged Monumental Creek, backing up water and flooding the town. It took a couple of days for the slide to happen, so getting out of its way wasn’t much of a feat. The valley filled in slowly, causing most of the buildings in the town to float.

Mining may have contributed to the slide, but the area was prone to such events and heavy rains were probably the main cause.

There was a bright side to the slide. That mud, moved free of charge by the forces of nature, made some areas easier to mine.

For years the remains of the town bobbed around in Roosevelt Lake. Nowadays you may find a few boards here and there along the shoreline, a reminder of a slow-moving disaster.

The photo of floating buildings on Roosevelt Lake is from the Idaho State Historical Society photo digital collection. It was taken sometime after 1909.

Published on April 15, 2020 04:00