Rick Just's Blog, page 130

April 8, 2021

Cassia Crossbills

The mountain bluebird is Idaho’s state bird. They are beautiful, though fairly common, creatures. They range from Alaska to Mexico and are found in every western state. But, what if there were a bird found only in Idaho? Would that bird knock the bluebird off its official perch?

Probably not. People love bluebirds. But there is a potential contender that may meet that only in Idaho test. American Ornithological Society publishes and annual checklist for birders. There are often a few changes on that list, and this year one of those changes is about the South Hills or Cassia Crossbill.

Crossbills are birds that look like they’ve been in a fight where someone knocked their beaks sideways. Their bills—this may not surprise you at this point—cross. This has nothing to do with avian pugilism. It’s a result of evolution. Each crossbill’s beak has evolved to match the particular shape of local pine cones. This didn’t happen overnight. Scientist think this particular bird has been around for about 6,000 years feasting off pine cones in the South Hills, and only in the South Hills of Idaho.

For more on this, check the link. If you want to see a South Hills Crossbill, take a little trip to Castle Rocks State Park. The manager there can point you in the right direction.

http://www.audubon.org/news/how-cross...

Photo by Adam Ciha, from the above-linked website.

Photo by Adam Ciha, from the above-linked website.

Probably not. People love bluebirds. But there is a potential contender that may meet that only in Idaho test. American Ornithological Society publishes and annual checklist for birders. There are often a few changes on that list, and this year one of those changes is about the South Hills or Cassia Crossbill.

Crossbills are birds that look like they’ve been in a fight where someone knocked their beaks sideways. Their bills—this may not surprise you at this point—cross. This has nothing to do with avian pugilism. It’s a result of evolution. Each crossbill’s beak has evolved to match the particular shape of local pine cones. This didn’t happen overnight. Scientist think this particular bird has been around for about 6,000 years feasting off pine cones in the South Hills, and only in the South Hills of Idaho.

For more on this, check the link. If you want to see a South Hills Crossbill, take a little trip to Castle Rocks State Park. The manager there can point you in the right direction.

http://www.audubon.org/news/how-cross...

Photo by Adam Ciha, from the above-linked website.

Photo by Adam Ciha, from the above-linked website.

Published on April 08, 2021 04:00

April 7, 2021

Taxing Gasoline

Idaho’s state gasoline tax hasn’t really raised in a hundred years. I have your attention with that statement, don’t I? It’s obviously wrong. Idaho’s only had a gasoline tax for 98 years. Nevertheless, bear with me.

In 1923, Idaho instituted its first tax on gasoline. The Legislature that year tacked two cents onto each gallon of gas for road building and repair. Gas cost about 22 cents a gallon. Automobile owners were generally supportive of the effort.

Today, Idaho’s state gasoline tax is 33 cents per gallon, so it has obviously gone up. But factor in inflation. That two cents from 1923 would have 31 cents of buying power today. So, it’s about the same.

The two-cent tax became a three-cent tax in 1925, a four-cent tax in 1927, and a nickel in 1929. The state was a in a road-building frenzy. The tax remained the same until 1945 when it went to 6 cents. It hung around in that neighborhood for 23 years, going to seven cents in 1968. Four years later the tax went to 8.5 cents a gallon. In 1976 it hit 9.5 cents. In 1981, the Legislature moved it to 11.5 cents. That was so much fun that they raised it an additional penny the next year. Giddy with that accomplishment, lawmakers moved it two cents in 1983 to 14.5 cents per gallon. It stayed there until 1988 when it jumped to 18 cents. In 1991 the tax moved 21 cents.

Are you seeing a pattern here?

The first time Idahoans started paying a quarter in tax for every gallon of gas was in 1996. That was more than a gallon of gas cost back in 1923 when the whole thing started. In 2015 the state gasoline tax went to 33 cents per gallon (effective in 2017), which is where it is today.

It was also in 2015 that the Legislature took notice of scoundrels like me who don’t pay any gasoline tax because we don’t buy any gasoline. They added $140 to annual registration fees for electric vehicles.

Are roads better today than they were in 1923 when all this began? Considerably. They’re also a lot more expensive to build and maintain, so look for future gas tax increases or some other method to help pay for them from some future Legislature.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

In 1923, Idaho instituted its first tax on gasoline. The Legislature that year tacked two cents onto each gallon of gas for road building and repair. Gas cost about 22 cents a gallon. Automobile owners were generally supportive of the effort.

Today, Idaho’s state gasoline tax is 33 cents per gallon, so it has obviously gone up. But factor in inflation. That two cents from 1923 would have 31 cents of buying power today. So, it’s about the same.

The two-cent tax became a three-cent tax in 1925, a four-cent tax in 1927, and a nickel in 1929. The state was a in a road-building frenzy. The tax remained the same until 1945 when it went to 6 cents. It hung around in that neighborhood for 23 years, going to seven cents in 1968. Four years later the tax went to 8.5 cents a gallon. In 1976 it hit 9.5 cents. In 1981, the Legislature moved it to 11.5 cents. That was so much fun that they raised it an additional penny the next year. Giddy with that accomplishment, lawmakers moved it two cents in 1983 to 14.5 cents per gallon. It stayed there until 1988 when it jumped to 18 cents. In 1991 the tax moved 21 cents.

Are you seeing a pattern here?

The first time Idahoans started paying a quarter in tax for every gallon of gas was in 1996. That was more than a gallon of gas cost back in 1923 when the whole thing started. In 2015 the state gasoline tax went to 33 cents per gallon (effective in 2017), which is where it is today.

It was also in 2015 that the Legislature took notice of scoundrels like me who don’t pay any gasoline tax because we don’t buy any gasoline. They added $140 to annual registration fees for electric vehicles.

Are roads better today than they were in 1923 when all this began? Considerably. They’re also a lot more expensive to build and maintain, so look for future gas tax increases or some other method to help pay for them from some future Legislature.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Some old pumps in Twin Falls in 1942. Photo by Russell Lee, Library of Congress.

Published on April 07, 2021 04:00

April 6, 2021

Aviator Cave

Spelunkers keep the location of most caves they know about secret. That’s to keep people who don’t have the proper training from hurting themselves and sometimes to protect cave environments.

There’s one cave in Idaho that gets a lot of extra protection. It’s called Aviator’s Cave and it is within the boundaries of the Idaho National Laboratory, which is in the desert between Idaho Falls and Arco. Since 1949 “the Site,” as it’s known locally, has been a national center for nuclear research. Because of the sensitive nature of that research, security at INL is high. In 1985, that included regular helicopter flyovers to make sure people weren’t intentionally or accidentally trespassing on the federal property.

In January 1985 pilot Mike Atwood was flying about 500 feet above the desert on a routine patrol when he spotted what looked like smoke. Circling around to investigate, he saw that it wasn’t smoke, but steam coming from a visible rift in the lava rock below. Atwood assumed it was condensation from warm air inside a lava tube hitting the sub-zero air in the desert above. He noted the GPS coordinates of the site and paid no more attention to it.

Lava tubes are common there in the Idaho desert, not far from Craters of the Moon National Monument. The caves were formed some 30,000 years ago when rivers of lava spewed from the earth, flowing downhill like water. The lava rivers would cool from the outside first forming a tube or roof over the molten lava still flowing beneath. Like a garden hose when the water is shut off the molten lava would drain out leaving a cave sometimes miles long.

Three years after his winter encounter with the steam and in a warmer season, Atwood’s curiosity surfaced. He decided to go back and investigate the hole he had found. When he flew to the coordinates he’d noted, Atwood saw that the vegetation around the dark shadow on the ground was a brighter shade of green than the surrounding rabbit brush.

About 30 feet from the hole he found a spot clear enough to land. As he walked closer to the cave he began to see buffalo skulls and other bones inside. He climbed down to the opening, stooped to get inside, and found that the cave opened up once past the lip. Standing up was easy.

It was immediately obvious that Atwood was not the first person to stand in that cave, though he was the first to stand there in a very long time. Among the scattered bones were obsidian chips and projectile points, evidence that native hunters had at least stopped in the cave if they had not lived there. Atwood, and later others, found more fragile evidence of human occupation, including objects made from plant material and fur.

Today this important archeological site remains doubly protected by its status as a place of scientific study and a place within a modern well-protected place of scientific study. Aviator’s Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

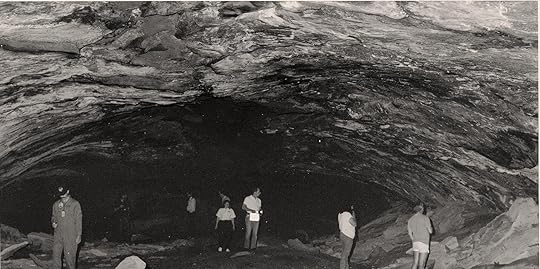

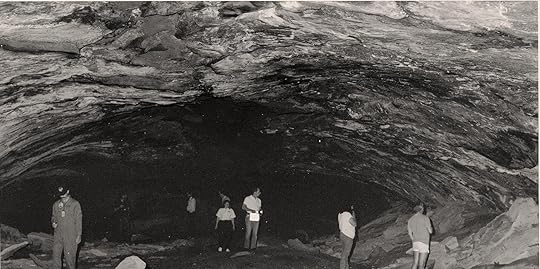

This INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

This INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

There’s one cave in Idaho that gets a lot of extra protection. It’s called Aviator’s Cave and it is within the boundaries of the Idaho National Laboratory, which is in the desert between Idaho Falls and Arco. Since 1949 “the Site,” as it’s known locally, has been a national center for nuclear research. Because of the sensitive nature of that research, security at INL is high. In 1985, that included regular helicopter flyovers to make sure people weren’t intentionally or accidentally trespassing on the federal property.

In January 1985 pilot Mike Atwood was flying about 500 feet above the desert on a routine patrol when he spotted what looked like smoke. Circling around to investigate, he saw that it wasn’t smoke, but steam coming from a visible rift in the lava rock below. Atwood assumed it was condensation from warm air inside a lava tube hitting the sub-zero air in the desert above. He noted the GPS coordinates of the site and paid no more attention to it.

Lava tubes are common there in the Idaho desert, not far from Craters of the Moon National Monument. The caves were formed some 30,000 years ago when rivers of lava spewed from the earth, flowing downhill like water. The lava rivers would cool from the outside first forming a tube or roof over the molten lava still flowing beneath. Like a garden hose when the water is shut off the molten lava would drain out leaving a cave sometimes miles long.

Three years after his winter encounter with the steam and in a warmer season, Atwood’s curiosity surfaced. He decided to go back and investigate the hole he had found. When he flew to the coordinates he’d noted, Atwood saw that the vegetation around the dark shadow on the ground was a brighter shade of green than the surrounding rabbit brush.

About 30 feet from the hole he found a spot clear enough to land. As he walked closer to the cave he began to see buffalo skulls and other bones inside. He climbed down to the opening, stooped to get inside, and found that the cave opened up once past the lip. Standing up was easy.

It was immediately obvious that Atwood was not the first person to stand in that cave, though he was the first to stand there in a very long time. Among the scattered bones were obsidian chips and projectile points, evidence that native hunters had at least stopped in the cave if they had not lived there. Atwood, and later others, found more fragile evidence of human occupation, including objects made from plant material and fur.

Today this important archeological site remains doubly protected by its status as a place of scientific study and a place within a modern well-protected place of scientific study. Aviator’s Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

This INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

This INL photo shows Shoshone-Bannock tribal members and archeologists exploring the cave.

Published on April 06, 2021 04:00

April 5, 2021

A Somewhat Reluctant Idahoan

Most Idahoans would rather live here than anywhere else. Today’s story is about a woman who desperately wanted to stay away, yet went on to popularize Idaho in illustration and story.

Mary Hallock grew up in New York, and received her education in Boston. She socialized with the elite of New England, but she fell in love with a civil engineer named Arthur Foote who had the grit of the West beneath his fingernails.

Mary Hallock Foote came West in the nation's Centennial year, 1876, but she did not come eagerly. Mrs. Foote once wrote, "No girl ever wanted less to go West with any man, or paid a man a greater compliment by doing so."

The Foote's lived in Idaho from 1883 to 1895, mostly in the Boise River Canyon near present day Lucky Peak Dam. It was a frustrating, heartbreaking time for them, but Mary made use of her hard experience. She was an illustrator for books and magazines of the era. In fact, she was once called the dean of women illustrators.

Encouraged by an editor to write as well, she became a popular author.

Mary Hallock Foote wrote many short stories, and a dozen novels. Much of her writing was based on her years in Idaho. Coeur d'Alene, Silver City, Boise, Thousand Springs, and Craters of the Moon were all settings for her stories.

In 1971 she was the subject of an enchanting—if controversial—story herself. Wallace Stegner's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose is based on the fascinating life of Mary Hallock Foote... a somewhat reluctant Idahoan.

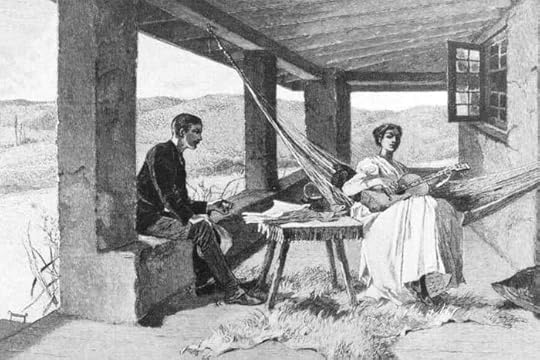

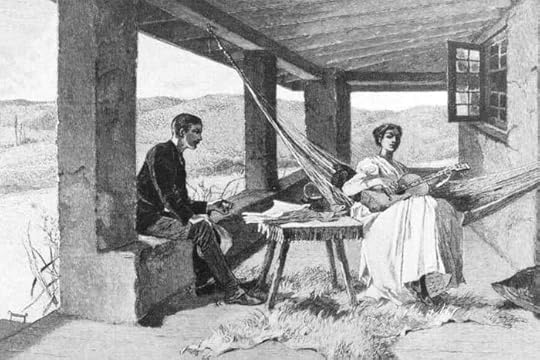

I’m pleased to say that a new Foote Park interpretive exhibit opened not long ago. You can reach it by crossing Lucky Peak Dam and taking the first road to your right. There is a restroom on site and plenty of parking. It’s well worth a few minutes of your time. One of Mary Hallock Foote's illustrations depicting a house much like the one she and Arthur Foote lived in near what is now the base of Lucky Peak Dam.

One of Mary Hallock Foote's illustrations depicting a house much like the one she and Arthur Foote lived in near what is now the base of Lucky Peak Dam.

Mary Hallock grew up in New York, and received her education in Boston. She socialized with the elite of New England, but she fell in love with a civil engineer named Arthur Foote who had the grit of the West beneath his fingernails.

Mary Hallock Foote came West in the nation's Centennial year, 1876, but she did not come eagerly. Mrs. Foote once wrote, "No girl ever wanted less to go West with any man, or paid a man a greater compliment by doing so."

The Foote's lived in Idaho from 1883 to 1895, mostly in the Boise River Canyon near present day Lucky Peak Dam. It was a frustrating, heartbreaking time for them, but Mary made use of her hard experience. She was an illustrator for books and magazines of the era. In fact, she was once called the dean of women illustrators.

Encouraged by an editor to write as well, she became a popular author.

Mary Hallock Foote wrote many short stories, and a dozen novels. Much of her writing was based on her years in Idaho. Coeur d'Alene, Silver City, Boise, Thousand Springs, and Craters of the Moon were all settings for her stories.

In 1971 she was the subject of an enchanting—if controversial—story herself. Wallace Stegner's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose is based on the fascinating life of Mary Hallock Foote... a somewhat reluctant Idahoan.

I’m pleased to say that a new Foote Park interpretive exhibit opened not long ago. You can reach it by crossing Lucky Peak Dam and taking the first road to your right. There is a restroom on site and plenty of parking. It’s well worth a few minutes of your time.

One of Mary Hallock Foote's illustrations depicting a house much like the one she and Arthur Foote lived in near what is now the base of Lucky Peak Dam.

One of Mary Hallock Foote's illustrations depicting a house much like the one she and Arthur Foote lived in near what is now the base of Lucky Peak Dam.

Published on April 05, 2021 04:00

April 4, 2021

Carjacking, Part II

Yesterday we started the story of the 1929 kidnapping of Idaho Lieutenant Governor William Barker Kinne, and two other men taken in a later carjacking. When we left off, a Latah County deputy had located two of the outlaws along the railroad tracks near Juliaetta.

At the point of his shotgun, Deputy Miles Pierce ordered the tramps out of the brush. One was a man with striking red hair. His name was Frank “Red” Lane, though he also used the alias Eward Fliss. The 24-year old was in possession of three handguns. The other man found sleeping in the brush was 20-year-old Engolf Snortland, who was described as tall and blond.

Their capture was followed a short time later by the capture of Albert Reynolds, 24, who had been spotted about 100 yards away by two local boys.

Meanwhile, John Kite, a local dairyman, had reported selling a couple of quarts of milk, a loaf of bread, and some jam to a scruffy looking pair of men who claimed they had just arrived on the morning freight and were in the area to pick cherries.

Within an hour Kendrick Town Constable Ernest Davis along with two Latah County deputies located the “cherry pickers” and arrested them without incident. The last fugitives were identified as 19-year-old Robert Livingston and “Seattle George” Norman, a well-known outlaw in the Northwest.

Lt. Gov Kinne would soon identify the four younger men as his kidnappers. Norman, who hadn’t taken part in that fiasco, was the ringleader of the group. He had sent the four to hijack a car so they could all rob a bank they had their eyes on in Pierce. Kidnapping was just a by-product of their need for a getaway car.

Their bumbling, violent actions in the kidnappings had marked the men as inept criminals. To underline that judgment, authorities found they had left the $200 they had stolen from Tribbey behind in his car when they abandoned it.

Local citizens, many of whom had spent hours searching for the abductors, were outraged at their vicious behavior.

When deputies escorted the outlaws to the Nez Perce County Jail in Lewiston, some 1,500 men were gathered in front of the building, many of them armed. While Sherriff Harry Dent created a diversion to distract the crowd, Lewiston Police Chief Eugene Gasser got the prisoners in through the back door.

Having avoided an angry crowd, the outlaws did not avoid the wrath of the law. The four carjackers pleaded guilty to kidnapping and were on their way to the Idaho State Prison in Boise, just eight days after the incident took place. Each got sentences of up to 25 years.

“Seattle George” Norman, the brains behind the plot to rob the bank, pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact to the kidnapping and was sentenced to two years in prison.

Although the planned bank robbery went ridiculously wrong it turned out that three of the four men involved in the kidnapping were experienced bank robbers. They were identified through fingerprints as the men who had kidnapped one of the owners of a bank in Gilmore City, Iowa. They had held his family prisoners overnight just weeks before. They forced the banker to open a safe in the morning and got away with $5,000.

Iowa wanted the men back. Governor Baldridge was quoted as saying, “Idaho would be extremely reluctant to let Lieutenant Governor Kinne’s abductors out of prison to go to Iowa or anywhere else for trial on other charges.”

Most of the culprits used aliases, but 19-year-old Engolf Snortland was the champion at names. He also went by Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds. Careful readers will note that the latter three aliases were the names of his partners in crime. That made it confusing for reporters who often used variations of the men’s names and aliases when listing them.

Snortland/Snoysland/Livingston/Lane/Reynolds was the most difficult to pin a name on, but it was Frank Lane who became someone else in criminal history.

Lane, according to Idaho State Prison records used the alias Edward Fliss. He was pardoned in April 1934. It took him about two seconds to land in seriously hot water again. This time Fliss was the name that went down in the records.

Lane/Fliss had met a prisoner by the name of William Dainard in the Idaho State Prison. Dainard was the mastermind behind the kidnapping of George Weyerhaeuser on May 24, 1935, one of the more infamous crimes in the Pacific Northwest. Fliss was convicted in relation to that kidnapping for helping Dainard exchange some of the ransom money. Fliss received another 10 years in prison for that.

This story started with Lieutenant Governor Kinne. Sadly, it ends with his death, not long after the abduction.

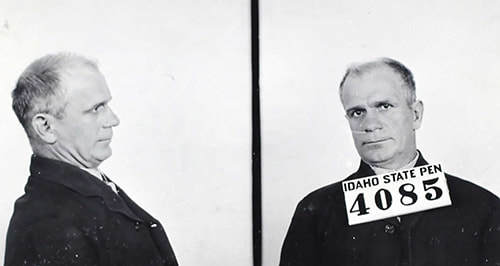

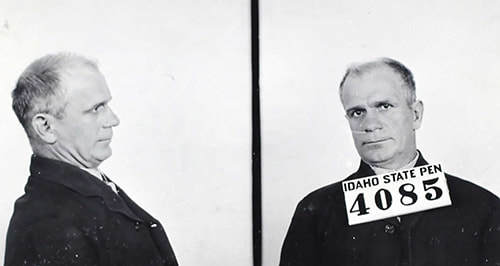

Kinne had a case of appendicitis, so diagnosed by a local doctor who thought it not especially serious. He delayed an operation, perhaps too long. Kinne’s appendix had ruptured, causing peritonitis. He died on October 1, 1929 at age 50, having been in office less than a year. "Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.

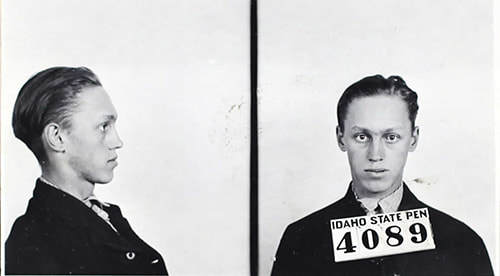

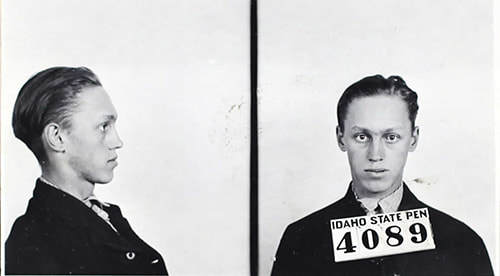

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.  Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.

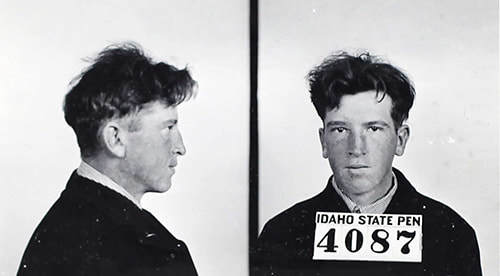

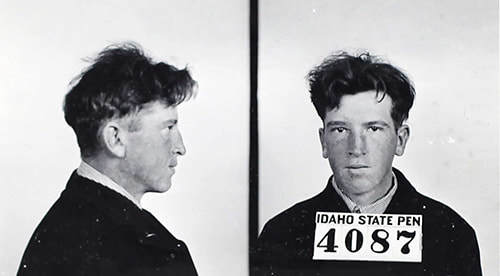

Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.  Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.

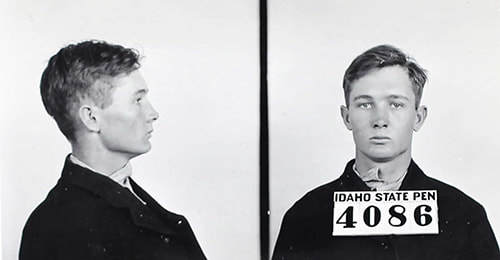

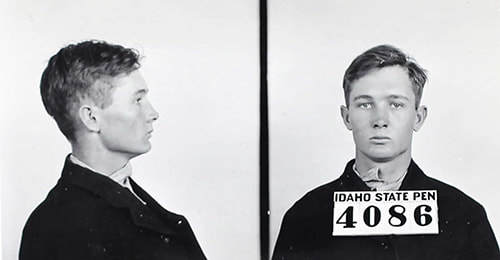

Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.  Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.

Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.  Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

At the point of his shotgun, Deputy Miles Pierce ordered the tramps out of the brush. One was a man with striking red hair. His name was Frank “Red” Lane, though he also used the alias Eward Fliss. The 24-year old was in possession of three handguns. The other man found sleeping in the brush was 20-year-old Engolf Snortland, who was described as tall and blond.

Their capture was followed a short time later by the capture of Albert Reynolds, 24, who had been spotted about 100 yards away by two local boys.

Meanwhile, John Kite, a local dairyman, had reported selling a couple of quarts of milk, a loaf of bread, and some jam to a scruffy looking pair of men who claimed they had just arrived on the morning freight and were in the area to pick cherries.

Within an hour Kendrick Town Constable Ernest Davis along with two Latah County deputies located the “cherry pickers” and arrested them without incident. The last fugitives were identified as 19-year-old Robert Livingston and “Seattle George” Norman, a well-known outlaw in the Northwest.

Lt. Gov Kinne would soon identify the four younger men as his kidnappers. Norman, who hadn’t taken part in that fiasco, was the ringleader of the group. He had sent the four to hijack a car so they could all rob a bank they had their eyes on in Pierce. Kidnapping was just a by-product of their need for a getaway car.

Their bumbling, violent actions in the kidnappings had marked the men as inept criminals. To underline that judgment, authorities found they had left the $200 they had stolen from Tribbey behind in his car when they abandoned it.

Local citizens, many of whom had spent hours searching for the abductors, were outraged at their vicious behavior.

When deputies escorted the outlaws to the Nez Perce County Jail in Lewiston, some 1,500 men were gathered in front of the building, many of them armed. While Sherriff Harry Dent created a diversion to distract the crowd, Lewiston Police Chief Eugene Gasser got the prisoners in through the back door.

Having avoided an angry crowd, the outlaws did not avoid the wrath of the law. The four carjackers pleaded guilty to kidnapping and were on their way to the Idaho State Prison in Boise, just eight days after the incident took place. Each got sentences of up to 25 years.

“Seattle George” Norman, the brains behind the plot to rob the bank, pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact to the kidnapping and was sentenced to two years in prison.

Although the planned bank robbery went ridiculously wrong it turned out that three of the four men involved in the kidnapping were experienced bank robbers. They were identified through fingerprints as the men who had kidnapped one of the owners of a bank in Gilmore City, Iowa. They had held his family prisoners overnight just weeks before. They forced the banker to open a safe in the morning and got away with $5,000.

Iowa wanted the men back. Governor Baldridge was quoted as saying, “Idaho would be extremely reluctant to let Lieutenant Governor Kinne’s abductors out of prison to go to Iowa or anywhere else for trial on other charges.”

Most of the culprits used aliases, but 19-year-old Engolf Snortland was the champion at names. He also went by Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds. Careful readers will note that the latter three aliases were the names of his partners in crime. That made it confusing for reporters who often used variations of the men’s names and aliases when listing them.

Snortland/Snoysland/Livingston/Lane/Reynolds was the most difficult to pin a name on, but it was Frank Lane who became someone else in criminal history.

Lane, according to Idaho State Prison records used the alias Edward Fliss. He was pardoned in April 1934. It took him about two seconds to land in seriously hot water again. This time Fliss was the name that went down in the records.

Lane/Fliss had met a prisoner by the name of William Dainard in the Idaho State Prison. Dainard was the mastermind behind the kidnapping of George Weyerhaeuser on May 24, 1935, one of the more infamous crimes in the Pacific Northwest. Fliss was convicted in relation to that kidnapping for helping Dainard exchange some of the ransom money. Fliss received another 10 years in prison for that.

This story started with Lieutenant Governor Kinne. Sadly, it ends with his death, not long after the abduction.

Kinne had a case of appendicitis, so diagnosed by a local doctor who thought it not especially serious. He delayed an operation, perhaps too long. Kinne’s appendix had ruptured, causing peritonitis. He died on October 1, 1929 at age 50, having been in office less than a year.

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.

"Seattle George" Norman was the brains behind the botched bank robbery. He didn't take part in the carjacking of the Lieutenant Governor Kinne.  Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.

Engolf Snortland, aka Egnos Snortland, Enos Snoysland, Robert Livingston, Frank Lane, and Albert Reynolds.  Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.

Frank Lane was one of the carjackers. He was later an accessory after the fact in the Weyerhaeuser kidnapping.  Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.

Robert Livingstone was one of those convicted in the carjacking and kidnapping.  Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

Albert Reynolds was 24 at the time of the crimes.

Published on April 04, 2021 04:00

April 3, 2021

Carjacking, 1929 Style

“I had driven about a half mile past Arrow when four men, all brandishing pistols, stepped out from the side of the road and halted me.”

That’s how Idaho Lieutenant Governor W.B. Kinne started the story about his abduction when talking to an Associated Press reporter in June 1929. Kinne, who had been elected the year before, was a well-to-do businessman from Orofino, so kidnapping for ransom came to the minds of officials when they discovered he was missing. Governor Baldridge considered calling out the National Guard to search for Kinne, but the incident was over before he could make that move.

It turned out the abductors weren’t carrying out a ransom scheme. They had no idea who Kinne was when they commandeered his car. They just needed a car. They probably took Kinne with them only to keep him from reporting the car theft.

As the lieutenant governor told the story the men forced him into the back of the car and onto the floor, one of them getting behind the wheel and driving on at a high rate of speed. That speed and a blown tire caused the car to hurtle off the road near Orofino and flip over. None of the men were badly hurt, but their newly acquired car was no longer a prize.

“The men forced me to walk out into a field, and as they did so another car pulled up,” Kene told reporters. “Two men, who I learned were W.L. Tribbey of the Idaho Building and Loan Association and Paul Kille, a lumber worker, got out of the car and as they walked toward us, the four men turned their guns on them. Kille was shot in the leg and clubbed over the head with guns until he went down. Tribbey was beaten badly.”

Now with three hostages the bandits piled into Tribbey’s car and raced off into the mountains. They found an isolated spot and tied the hostages to a tree. One of the bandits stood guard, while the remaining three drove off, only to return about four hours later without explanation.

The men took $14 from the wounded Kille, and $200 from Tribbey. They threatened the bound hostages with death and told them not to move for at least four hours. Then, all four of the highwaymen drove off in the stolen car.

Tribbey ignored their threat and freed himself within about 15 minutes. He untied the others and they all set off on foot for the nearby town of Greer.

The harrowing story told by the victims set off a four-state manhunt for the car thieves.

The kidnappers were described as being between 18 and 25 years of age, armed, and “desperate.” Law enforcement was on the lookout for Tribbey’s blue sedan, plate number 249-060.

Citizens were outraged by the kidnappings. Every able-bodied man who could take off work in Nez Perce, Lewis, Latah, and Clearwater counties joined the search. Indian trackers and Boy Scouts joined farmers and loggers. Bloodhounds were flown in from Yakima.

For two days thousands of men searched for the four assailants, checking cars at intersections, and looking into outbuildings. Nothing turned up. Then early in the morning, Friday, June 14, Latah County Deputy Miles Pierce spotted two men asleep in undergrowth along the railroad tracks near Juliaetta. Those men woke to find a shotgun in their faces.

We’ll continue the story in tomorrow’s Speaking of Idaho post.

That’s how Idaho Lieutenant Governor W.B. Kinne started the story about his abduction when talking to an Associated Press reporter in June 1929. Kinne, who had been elected the year before, was a well-to-do businessman from Orofino, so kidnapping for ransom came to the minds of officials when they discovered he was missing. Governor Baldridge considered calling out the National Guard to search for Kinne, but the incident was over before he could make that move.

It turned out the abductors weren’t carrying out a ransom scheme. They had no idea who Kinne was when they commandeered his car. They just needed a car. They probably took Kinne with them only to keep him from reporting the car theft.

As the lieutenant governor told the story the men forced him into the back of the car and onto the floor, one of them getting behind the wheel and driving on at a high rate of speed. That speed and a blown tire caused the car to hurtle off the road near Orofino and flip over. None of the men were badly hurt, but their newly acquired car was no longer a prize.

“The men forced me to walk out into a field, and as they did so another car pulled up,” Kene told reporters. “Two men, who I learned were W.L. Tribbey of the Idaho Building and Loan Association and Paul Kille, a lumber worker, got out of the car and as they walked toward us, the four men turned their guns on them. Kille was shot in the leg and clubbed over the head with guns until he went down. Tribbey was beaten badly.”

Now with three hostages the bandits piled into Tribbey’s car and raced off into the mountains. They found an isolated spot and tied the hostages to a tree. One of the bandits stood guard, while the remaining three drove off, only to return about four hours later without explanation.

The men took $14 from the wounded Kille, and $200 from Tribbey. They threatened the bound hostages with death and told them not to move for at least four hours. Then, all four of the highwaymen drove off in the stolen car.

Tribbey ignored their threat and freed himself within about 15 minutes. He untied the others and they all set off on foot for the nearby town of Greer.

The harrowing story told by the victims set off a four-state manhunt for the car thieves.

The kidnappers were described as being between 18 and 25 years of age, armed, and “desperate.” Law enforcement was on the lookout for Tribbey’s blue sedan, plate number 249-060.

Citizens were outraged by the kidnappings. Every able-bodied man who could take off work in Nez Perce, Lewis, Latah, and Clearwater counties joined the search. Indian trackers and Boy Scouts joined farmers and loggers. Bloodhounds were flown in from Yakima.

For two days thousands of men searched for the four assailants, checking cars at intersections, and looking into outbuildings. Nothing turned up. Then early in the morning, Friday, June 14, Latah County Deputy Miles Pierce spotted two men asleep in undergrowth along the railroad tracks near Juliaetta. Those men woke to find a shotgun in their faces.

We’ll continue the story in tomorrow’s Speaking of Idaho post.

Published on April 03, 2021 04:00

April 2, 2021

Wyatt Earp in Murray

Have you ever heard of a little Idaho town called Murray? Maybe not, but I bet you've heard of a couple of Western characters called Wyatt Earp and Calamity Jane. They knew all about Murray.

Murray, Idaho, located in the mountains just north of Wallace, has fewer than 100 residents nowadays, but in the mid-1880s it was a thriving boomtown. A gold rush came to Murray in 1883. Gold meant miners, and miners meant saloons, supply stores, and a red-light district. The latter attracted some colorful ladies like Terrible Edith, Molly B. Dam, and Calamity Jane.

Virgil and Wyatt Earp had some mining claims in the area, and they ran a saloon in nearby Eagle City. An 1884 newspaper ad for their saloon called it the "finest appointed saloon in the Coeur d'Alenes... with the finest brand of foreign and domestic liquors to be found in the United States." The ad also suggested that customers of the Earp brothers' White Elephant Saloon, should come "and see the Elephant."

Virgil and Wyatt Earp didn't stick around long, though. Murray boomed for about a year and a half, then just hung on for another 25 or 30 years. During its life as a mining center, about $1 million worth of gold came out of Murray, though.

The little town is still worth visiting. The Sprag Pole Museum has a fascinating collection of mining tools, whiskey decanters, and guns. It also claims to have the world's longest wooden chain. It's 120 feet in length. Can your wooden chain beat that?

Murray, Idaho, located in the mountains just north of Wallace, has fewer than 100 residents nowadays, but in the mid-1880s it was a thriving boomtown. A gold rush came to Murray in 1883. Gold meant miners, and miners meant saloons, supply stores, and a red-light district. The latter attracted some colorful ladies like Terrible Edith, Molly B. Dam, and Calamity Jane.

Virgil and Wyatt Earp had some mining claims in the area, and they ran a saloon in nearby Eagle City. An 1884 newspaper ad for their saloon called it the "finest appointed saloon in the Coeur d'Alenes... with the finest brand of foreign and domestic liquors to be found in the United States." The ad also suggested that customers of the Earp brothers' White Elephant Saloon, should come "and see the Elephant."

Virgil and Wyatt Earp didn't stick around long, though. Murray boomed for about a year and a half, then just hung on for another 25 or 30 years. During its life as a mining center, about $1 million worth of gold came out of Murray, though.

The little town is still worth visiting. The Sprag Pole Museum has a fascinating collection of mining tools, whiskey decanters, and guns. It also claims to have the world's longest wooden chain. It's 120 feet in length. Can your wooden chain beat that?

Published on April 02, 2021 04:00

April 1, 2021

St. Maries Olympian

Georgia Coleman, center in the photo, was born in St. Maries, Idaho. She was an Olympic champion, but the Idaho Statesman didn’t make the Idaho connection when reporting on her prowess in the pool at the time so she may not have lived long in the state.

Coleman won the silver medal in the 10-metre platform and the bronze medal in the 3-metre springboard competition in 1928 in Amsterdam. Four years later, in Los Angeles she won the gold medal in the 3-metre springboard event and the silver medal in the 10-metre platform competition. She dominated diving competition for several years.

Coleman contracted polio in 1937. She recovered enough to start swimming again, but two years later died from polio-related pneumonia.

Georgia Coleman was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1966.

You can see Coleman demonstrating her dives on YouTube.

Coleman won the silver medal in the 10-metre platform and the bronze medal in the 3-metre springboard competition in 1928 in Amsterdam. Four years later, in Los Angeles she won the gold medal in the 3-metre springboard event and the silver medal in the 10-metre platform competition. She dominated diving competition for several years.

Coleman contracted polio in 1937. She recovered enough to start swimming again, but two years later died from polio-related pneumonia.

Georgia Coleman was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1966.

You can see Coleman demonstrating her dives on YouTube.

Published on April 01, 2021 04:00

March 31, 2021

Pop Quiz

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). Which of these was NOT a name of one of Hemingway’s cats?

A. Boise

B. Big Boy Peterson

C. Good Will

D. Hailey

E. Princessa

2). What was the tallest dam in the world in 1920?

A. Owyhee Reservoir Dam

B. Arrowrock Dam

C. Lucky Peak Dam

D. Palisades Dam

E. American Falls Dam

3). Where did Charlie Pride play baseball in 1953?

A. Idaho Falls

B. Twin Falls

C. Pocatello

D. Boise

E. Lewiston

4). Who probably invented the first snowmobile that appeared in Idaho?

A. Henry Ford

B. Joseph Sherwood

C. Chuck Wells

D. Philo T. Farnsworth

E. Don Samuelson

5) What year was the prison riot that convinced Idaho to build a new penitentiary?

A. 1951

B. 1953

C. 1971

D. 1973

E. Trick question. No riot was the impetus for building the new prison. Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, D

2, B

3, D

4, B

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). Which of these was NOT a name of one of Hemingway’s cats?

A. Boise

B. Big Boy Peterson

C. Good Will

D. Hailey

E. Princessa

2). What was the tallest dam in the world in 1920?

A. Owyhee Reservoir Dam

B. Arrowrock Dam

C. Lucky Peak Dam

D. Palisades Dam

E. American Falls Dam

3). Where did Charlie Pride play baseball in 1953?

A. Idaho Falls

B. Twin Falls

C. Pocatello

D. Boise

E. Lewiston

4). Who probably invented the first snowmobile that appeared in Idaho?

A. Henry Ford

B. Joseph Sherwood

C. Chuck Wells

D. Philo T. Farnsworth

E. Don Samuelson

5) What year was the prison riot that convinced Idaho to build a new penitentiary?

A. 1951

B. 1953

C. 1971

D. 1973

E. Trick question. No riot was the impetus for building the new prison.

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, D

2, B

3, D

4, B

5, E

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on March 31, 2021 04:00

March 30, 2021

Prison Riots

In September 1971, the top story was all about a prison riot where 43 staff and inmates died. To this day, the word Attica is synonymous with prison riots. A month before that tragic event, an Idaho prison riot was in the news.

High temperatures in Boise had hovered around 100 degrees for ten days. On August 9 the thermometer hit 102. The cooldown to 98 degrees on August 10 was hardly noticeable, especially in the old cell blocks at the Idaho State Penitentiary on the outskirts of Boise. It could get up to 118 on the upper decks.

Cooler quarters for some of the inmates were closed that day because officials had found two escape tunnels in the “honor dormitory.” That detonated four hours of rioting. The prisoners set fires in the bakery and the social services building. Two inmates were stabbed in the melee.

After guards and Ada County deputies brought the incident under control, more complaints about conditions at the 99-year-old prison surfaced. A lack of sanitation was second only to the heat on the list of concerns for the inmates. Prisoners claimed to have found a dead rat in the dilapidated water tank on the hill above the prison, along with rat droppings. Inmates complained of filthy conditions in the kitchen and a lack of sanitation in the prison clinic.

Authorities brought in a dozen industrial fans and let inmates stay outside for a time after the riot and addressed some other prisoner complaints.

It was not the first riot at the prison, and it would not be the last. In 1952 300 prisoners rioted for five hours, setting fire to one of the dormitories. That dust-up was quelled when 100 heavily armed officers stood on the walls of the prison and fired teargas into the recreation building where inmates were gathered. Complaints about a new convict grievance committee set that disturbance off.

The last riot at the old prison was the one most remembered. It is also commonly misremembered as the reason Idaho built a new prison in the desert south of Boise. The new prison complex had been in the works for at least 13 years when the 1973 riot broke out. In fact, the riot started when an inmate who was already at the new maximum-security site was transported to the clinic at the old prison for treatment of a minor injury. When it was time to go back, inmate Larry Trujillo, 25, refused to go. Other inmates threateningly gathered around the guards attempting to move Trujillo.

While a discussion about moving the prisoner was taking place between the warden and the inmate council, fires broke out in four prison buildings. It was later learned that inmates accused guards of beating Trujillo and another inmate. That’s what sparked the riot of more than 200 prisoners.

The fires destroyed the prison chapel and the kitchen-dining hall, with heavy damage to the tailor shop, laundry, and an administrative office. The flames left their signature on the Old Idaho Penitentiary as we know it today. Just three weeks after the riot, Idaho State Historical Society Director Arthur A. Hart had the foresight to implore authorities to leave the bones of the burned-out buildings in place to preserve the history of the riot and broached the subject of maintaining the old prison as an Idaho state historical site.

Although the 1973 riot was not the impetus for constructing the new $13 million dollar prison, it did give officials a push to move inmates as quickly as possible. The new prison opened December 3, 1973. The Idaho Statesman in a caption on a photo of shiny new bars, noted that “if anyone can get out of here, he doesn’t have many options on where to hide, because the new prison is in the middle of barren sagebrush land.”

The first escape came ten days later.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

High temperatures in Boise had hovered around 100 degrees for ten days. On August 9 the thermometer hit 102. The cooldown to 98 degrees on August 10 was hardly noticeable, especially in the old cell blocks at the Idaho State Penitentiary on the outskirts of Boise. It could get up to 118 on the upper decks.

Cooler quarters for some of the inmates were closed that day because officials had found two escape tunnels in the “honor dormitory.” That detonated four hours of rioting. The prisoners set fires in the bakery and the social services building. Two inmates were stabbed in the melee.

After guards and Ada County deputies brought the incident under control, more complaints about conditions at the 99-year-old prison surfaced. A lack of sanitation was second only to the heat on the list of concerns for the inmates. Prisoners claimed to have found a dead rat in the dilapidated water tank on the hill above the prison, along with rat droppings. Inmates complained of filthy conditions in the kitchen and a lack of sanitation in the prison clinic.

Authorities brought in a dozen industrial fans and let inmates stay outside for a time after the riot and addressed some other prisoner complaints.

It was not the first riot at the prison, and it would not be the last. In 1952 300 prisoners rioted for five hours, setting fire to one of the dormitories. That dust-up was quelled when 100 heavily armed officers stood on the walls of the prison and fired teargas into the recreation building where inmates were gathered. Complaints about a new convict grievance committee set that disturbance off.

The last riot at the old prison was the one most remembered. It is also commonly misremembered as the reason Idaho built a new prison in the desert south of Boise. The new prison complex had been in the works for at least 13 years when the 1973 riot broke out. In fact, the riot started when an inmate who was already at the new maximum-security site was transported to the clinic at the old prison for treatment of a minor injury. When it was time to go back, inmate Larry Trujillo, 25, refused to go. Other inmates threateningly gathered around the guards attempting to move Trujillo.

While a discussion about moving the prisoner was taking place between the warden and the inmate council, fires broke out in four prison buildings. It was later learned that inmates accused guards of beating Trujillo and another inmate. That’s what sparked the riot of more than 200 prisoners.

The fires destroyed the prison chapel and the kitchen-dining hall, with heavy damage to the tailor shop, laundry, and an administrative office. The flames left their signature on the Old Idaho Penitentiary as we know it today. Just three weeks after the riot, Idaho State Historical Society Director Arthur A. Hart had the foresight to implore authorities to leave the bones of the burned-out buildings in place to preserve the history of the riot and broached the subject of maintaining the old prison as an Idaho state historical site.

Although the 1973 riot was not the impetus for constructing the new $13 million dollar prison, it did give officials a push to move inmates as quickly as possible. The new prison opened December 3, 1973. The Idaho Statesman in a caption on a photo of shiny new bars, noted that “if anyone can get out of here, he doesn’t have many options on where to hide, because the new prison is in the middle of barren sagebrush land.”

The first escape came ten days later.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

The burned-out prison chapel shortly after the 1973 Idaho State Penitentiary riot. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society.

Published on March 30, 2021 04:00