Rick Just's Blog, page 123

June 18, 2021

POWs at Farragut

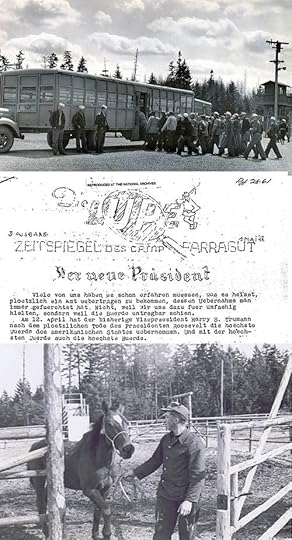

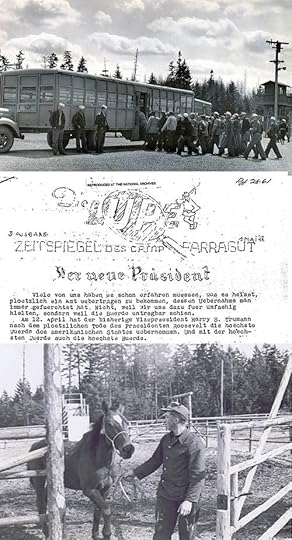

The top picture is of a group of troops at Farragut Naval Training Station getting ready to board “cattle cars” for some work assignment. Do you notice anything unusual about them?

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

The second photo gives you a clue. Their camp newsletter was in German. This particular issue announces the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1945. Roosevelt had visited FNTS in 1942.

Perhaps as many as 926 POWs spent time at Farragut, clearing brush and shoveling coal mostly, but also as bakers, cooks, storekeepers, and firefighters. Long after the war, a former prisoner would occasionally show up at Farragut State Park for a visit. They generally had good memories.

The bottom photo is one of the POWs working with a horse on stable detail. His name was Werner Wagner. The horse’s name was Dime.

Published on June 18, 2021 04:00

June 17, 2021

The Manning Crevice Bridge

It’s time for our occasional Then and Now feature.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) operated 248 camps in Idaho between 1933 and 1941. The famous jobs program kept 88,000 young men working in Idaho, most of them from far-flung states across the country. It was a big jobs program for Idaho men, too. According to Ivar Nelson, who with his wife Patricia Hart, has amassed a vast collection of material on the CCCs in Idaho, one in five Idaho men—about 20,000—served in the CCC during the depression. Check out their Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection.

The CCCs built roads, cattle watering ponds, Forest Service buildings, trails, and most of the facilities in Heyburn State Park. They planted trees and fought soil erosion. And they built a bridge across the Salmon River.

The Manning Crevice Bridge, about 14 miles upstream from Riggins, was a 248-foot-long suspension bridge that was part of an ill-conceived road project. That project was a plan to make a road along the Salmon from North Fork to Riggins, uniting the state roughly from border to border. The CCCs started on both ends, meaning to meet in the middle, perhaps driving the equivalent of a golden spike to celebrate.

People who valued the wildness of the river were opposed to it, but the CCCs plunged on, oblivious to politics. They made good progress on both ends until steep canyons started to bring a dose of reality to the project. By the time World War II kicked up, sending young men on another mission, it was clear that funding and topography would kill the project.

The Manning Crevice Bridge, named for John C. Manning, a CCC worker who lost his life during its construction, was probably the most visible relic of the venture. It served back country travel for decades.

The bridge was deemed unsafe a few years ago by the Federal Highway Administration. It didn’t get a lot of traffic, but it was the only access to that side of the river, so they determined they needed a safe, one-lane bridge. The general contractor that won the bid, the RSCI Group in Boise, also won an award for the project, which was completed in 2019. The new Manning Crevice Bridge is only the seventh structure in the world to use an asymmetrical, single tower bridge design. It is the first such bridge in North America (see photo below). Though of modern design the bridge was built using a weathering steel that provides a densely rusted patina that gives it an antique look while protecting the structure.

The current Manning Crevice Bridge

The current Manning Crevice Bridge

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) operated 248 camps in Idaho between 1933 and 1941. The famous jobs program kept 88,000 young men working in Idaho, most of them from far-flung states across the country. It was a big jobs program for Idaho men, too. According to Ivar Nelson, who with his wife Patricia Hart, has amassed a vast collection of material on the CCCs in Idaho, one in five Idaho men—about 20,000—served in the CCC during the depression. Check out their Civilian Conservation Corps in Idaho Collection.

The CCCs built roads, cattle watering ponds, Forest Service buildings, trails, and most of the facilities in Heyburn State Park. They planted trees and fought soil erosion. And they built a bridge across the Salmon River.

The Manning Crevice Bridge, about 14 miles upstream from Riggins, was a 248-foot-long suspension bridge that was part of an ill-conceived road project. That project was a plan to make a road along the Salmon from North Fork to Riggins, uniting the state roughly from border to border. The CCCs started on both ends, meaning to meet in the middle, perhaps driving the equivalent of a golden spike to celebrate.

People who valued the wildness of the river were opposed to it, but the CCCs plunged on, oblivious to politics. They made good progress on both ends until steep canyons started to bring a dose of reality to the project. By the time World War II kicked up, sending young men on another mission, it was clear that funding and topography would kill the project.

The Manning Crevice Bridge, named for John C. Manning, a CCC worker who lost his life during its construction, was probably the most visible relic of the venture. It served back country travel for decades.

The bridge was deemed unsafe a few years ago by the Federal Highway Administration. It didn’t get a lot of traffic, but it was the only access to that side of the river, so they determined they needed a safe, one-lane bridge. The general contractor that won the bid, the RSCI Group in Boise, also won an award for the project, which was completed in 2019. The new Manning Crevice Bridge is only the seventh structure in the world to use an asymmetrical, single tower bridge design. It is the first such bridge in North America (see photo below). Though of modern design the bridge was built using a weathering steel that provides a densely rusted patina that gives it an antique look while protecting the structure.

The current Manning Crevice Bridge

The current Manning Crevice Bridge

Published on June 17, 2021 04:00

June 16, 2021

The Abes in Boise

Boise has two statues of President Abraham Lincoln. The first is on the capitol grounds in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest Lincoln statue in the West. It was first installed at the Soldiers Home in 1915, then moved to the Idaho Veterans Home in East Boise. In 2009 it was moved to its present location. It's one of six duplicates of a piece sculpted by Alphonso Pelzer. The original statue is in New Jersey.

The other Lincoln is a giant sculpture, 9 feet tall, and he’s sitting on a bench. You can sit with him in Julia Davis Park. Why two Lincolns in Idaho? He signed the act creating Idaho Territory in 1863. Fun facts: the sitting Lincoln sculpture is a copy of one created by Gutzon Borglum. In spite of his weird name, you need to know that he carved the faces on Mount Rushmore and that he was born in St. Charles, Idaho Territory, in 1867. Oh, and the original of the sitting Lincoln is also in New Jersey.

The other Lincoln is a giant sculpture, 9 feet tall, and he’s sitting on a bench. You can sit with him in Julia Davis Park. Why two Lincolns in Idaho? He signed the act creating Idaho Territory in 1863. Fun facts: the sitting Lincoln sculpture is a copy of one created by Gutzon Borglum. In spite of his weird name, you need to know that he carved the faces on Mount Rushmore and that he was born in St. Charles, Idaho Territory, in 1867. Oh, and the original of the sitting Lincoln is also in New Jersey.

Published on June 16, 2021 04:00

June 15, 2021

A Visit from the Liberty Bell

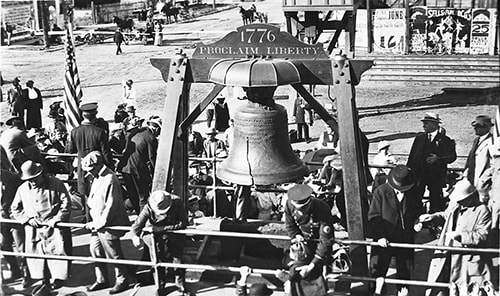

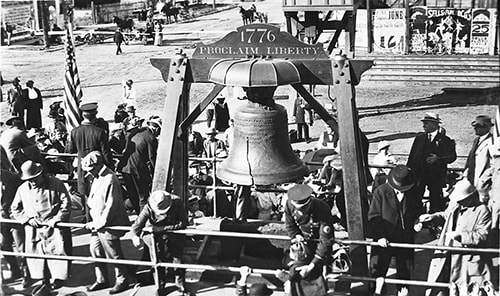

Have you seen the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia? Or, are you waiting for it to come to you?

Getting a visit from the bell is unlikely today, but it once travelled quite a lot to fairs and patriotic assemblages. On its most recent trip from Philadelphia it made it all the way to Idaho. That was over a hundred years ago.

The Liberty Bell was the centerpiece of a bond drive to support World War I. Mounted on a railroad flatcar it toured the United States in 1915 on its way to the Panama-Pacific International exposition in San Francisco and back. By some estimates, half the people in the country turned out to see it.

The bell was on view in Boise from 7:15 to 8 am, July 13, 1915. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people came to see it. The arrival of the bell was front page news in the Meridian Times even though the bell didn’t make a stop in Meridian. It did slow down. About 8,000 people turned out in Caldwell for the 25-minute stop there, before it steamed away into Oregon for the final leg of its trip to San Francisco.

The bell was then, and remains today, a beloved US icon. Why, exactly? Partly because of its inscription, and partly because of a popular fiction that grew up around it.

The bell was cast in London in 1752, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, and inscribed with a quote from Leviticus, “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.”

The bell cracked right away when it was first rung in Philadelphia. It was twice recast to repair it.

A popular story had it that the bell rang out on July 4, 1776, announcing the Declaration of Independence. No such announcement was made that day, but historians agree it was probably one of many bells that rang in the city on July 8, when the announcement was made.

The original crack having been repaired, the bell cracked again—and remained so—sometime in the early 19th century.

As a symbol of liberty, it was a war bond star. Americans bought an average of $170 each in the Liberty Bell war bond drives.

Getting a visit from the bell is unlikely today, but it once travelled quite a lot to fairs and patriotic assemblages. On its most recent trip from Philadelphia it made it all the way to Idaho. That was over a hundred years ago.

The Liberty Bell was the centerpiece of a bond drive to support World War I. Mounted on a railroad flatcar it toured the United States in 1915 on its way to the Panama-Pacific International exposition in San Francisco and back. By some estimates, half the people in the country turned out to see it.

The bell was on view in Boise from 7:15 to 8 am, July 13, 1915. Between 15,000 and 20,000 people came to see it. The arrival of the bell was front page news in the Meridian Times even though the bell didn’t make a stop in Meridian. It did slow down. About 8,000 people turned out in Caldwell for the 25-minute stop there, before it steamed away into Oregon for the final leg of its trip to San Francisco.

The bell was then, and remains today, a beloved US icon. Why, exactly? Partly because of its inscription, and partly because of a popular fiction that grew up around it.

The bell was cast in London in 1752, commissioned by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, and inscribed with a quote from Leviticus, “Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof.”

The bell cracked right away when it was first rung in Philadelphia. It was twice recast to repair it.

A popular story had it that the bell rang out on July 4, 1776, announcing the Declaration of Independence. No such announcement was made that day, but historians agree it was probably one of many bells that rang in the city on July 8, when the announcement was made.

The original crack having been repaired, the bell cracked again—and remained so—sometime in the early 19th century.

As a symbol of liberty, it was a war bond star. Americans bought an average of $170 each in the Liberty Bell war bond drives.

Published on June 15, 2021 04:00

June 14, 2021

Floating on a Float

I’ve written several times about Boise’s Natatorium in the past, about its beauty, about its use of Boise’s naturally hot water, about a fight with the county prosecutor, and even about a holdup at the Nat.

Today, I’m writing about nearly nothing at all. I ran across this photo of a 1925 parade float featuring a dozen beauties promoting the Natatorium. I just thought you’d enjoy it. Notice how a couple of the women are “floating” chest-deep in the “water.”

Idaho State Historical Society Photo

Idaho State Historical Society Photo

Today, I’m writing about nearly nothing at all. I ran across this photo of a 1925 parade float featuring a dozen beauties promoting the Natatorium. I just thought you’d enjoy it. Notice how a couple of the women are “floating” chest-deep in the “water.”

Idaho State Historical Society Photo

Idaho State Historical Society Photo

Published on June 14, 2021 04:00

June 13, 2021

A Lewiston Flight School

From 1938 until 1944 the federal government operated a Civilian Aeronautics Administration program to train pilots. It was called the Civilian Pilot Training Program. The government would pay for 72 hours of ground instruction and 35-50 hours of flight instruction to create more civilian pilots. During later iterations of the program military pilots got their first taste of the air through an expanded program.

Lewiston State Normal School was one of 1,132 educational institutions to create a pilot training program. They contracted with Zimmerly Air Transport to train Navy cadets from 1942 to 1943.

The top photo shows an airport shuttle for the program, while the bottom picture, is the “9:20 flight of Intermediate students taxiing in a zig-zag manner to the end of the field for takeoff.” Both photos are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Lewiston State Normal School was one of 1,132 educational institutions to create a pilot training program. They contracted with Zimmerly Air Transport to train Navy cadets from 1942 to 1943.

The top photo shows an airport shuttle for the program, while the bottom picture, is the “9:20 flight of Intermediate students taxiing in a zig-zag manner to the end of the field for takeoff.” Both photos are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on June 13, 2021 04:00

June 12, 2021

Boise's Lawyer Statue

This Statue is in the park next to the Borah Station Post Office near the statehouse in Boise. It’s called Hospitality of the Nez Perce. It depicts Nez Perce Chief Twisted Hair discussing area geography with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in Sept 1805. The chief’s son, Lawyer, portrayed at about age eight, inspects trade items at their feet: Nez Perce camas roots, a salmon, Euro-American cloth, and a knife.

Lawyer, or Hallalhotsoot as he was known to the Nez Perce, would become a chief himself in later life and play a prominent role in the Flight of the Nez Perce.

Doug Hyde created the statue. He is a nationally acclaimed Native American artist and Nez Perce descendent who grew up in Lewiston. The statue was donated to the State of Idaho in 2006 by Carol MacGregor, an Idaho native who was a rancher, professor, and the author of several books on Idaho history.

Lawyer, or Hallalhotsoot as he was known to the Nez Perce, would become a chief himself in later life and play a prominent role in the Flight of the Nez Perce.

Doug Hyde created the statue. He is a nationally acclaimed Native American artist and Nez Perce descendent who grew up in Lewiston. The statue was donated to the State of Idaho in 2006 by Carol MacGregor, an Idaho native who was a rancher, professor, and the author of several books on Idaho history.

Published on June 12, 2021 04:00

June 11, 2021

The Idaho Stop

Today’s post is another in our occasional Then and Now series.

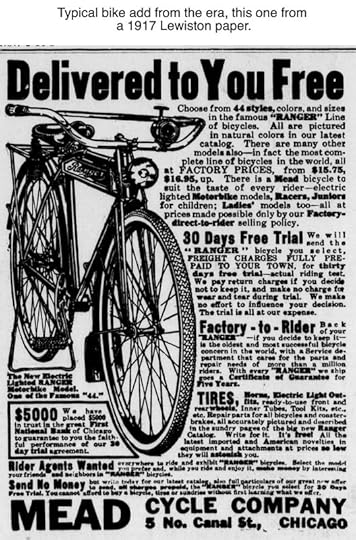

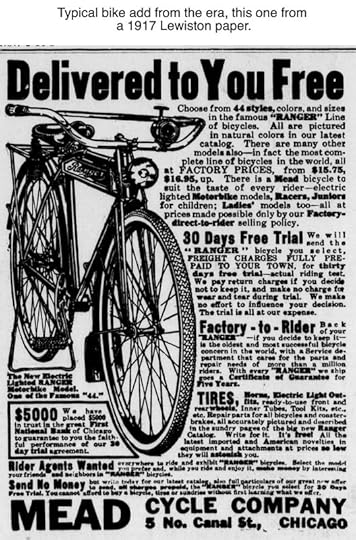

Bicycles have been in Idaho since territorial days. Unlike horse drawn conveyances, bikes were not replaced by automobiles.

In May, 1911, the Boise Evening Capital News was effusive about the future of the bicycle. “No question about it—the bicycle is coming into its own again. Its fine record in the war, its many-sided utility in modern business, its wonderful influence for health, coupled with its undoubted economy and convenience—all have combined to make it even more desirable than before.”

A.P. Tyler, the local Firestone dealer was enthusiastic about bicycles, and the “Non-Skid” tires Firestone was selling. “I look for a big year for the bicycle trade generally. (Bicycles) meet a distinct need in our modern life—as the only really practical self-propelled vehicle.”

Fast forward to 1982 when Idaho showed its love for bicycles in a unique way. The Legislature that year was revising traffic rules and decided to stop cluttering up judicial calendars with “technical violations” of traffic control devices, i.e., stop signs. That was the invention of a law that has become known as the Idaho Stop. Bike riders in Idaho can treat a stop sign the same way drivers treat a yield sign. That is, if the coast is clear they can roll right through it. A later revision to Idaho code made it legal for bike riders to treat a stop light the same way vehicle drivers treat a stop sign: Stop, check to see if the way is clear, then proceed.

Several other jurisdictions across the country have tried implementing the Idaho Stop for bicyclists. To date, Idaho is the only place it is legal statewide.

Bicycles have been in Idaho since territorial days. Unlike horse drawn conveyances, bikes were not replaced by automobiles.

In May, 1911, the Boise Evening Capital News was effusive about the future of the bicycle. “No question about it—the bicycle is coming into its own again. Its fine record in the war, its many-sided utility in modern business, its wonderful influence for health, coupled with its undoubted economy and convenience—all have combined to make it even more desirable than before.”

A.P. Tyler, the local Firestone dealer was enthusiastic about bicycles, and the “Non-Skid” tires Firestone was selling. “I look for a big year for the bicycle trade generally. (Bicycles) meet a distinct need in our modern life—as the only really practical self-propelled vehicle.”

Fast forward to 1982 when Idaho showed its love for bicycles in a unique way. The Legislature that year was revising traffic rules and decided to stop cluttering up judicial calendars with “technical violations” of traffic control devices, i.e., stop signs. That was the invention of a law that has become known as the Idaho Stop. Bike riders in Idaho can treat a stop sign the same way drivers treat a yield sign. That is, if the coast is clear they can roll right through it. A later revision to Idaho code made it legal for bike riders to treat a stop light the same way vehicle drivers treat a stop sign: Stop, check to see if the way is clear, then proceed.

Several other jurisdictions across the country have tried implementing the Idaho Stop for bicyclists. To date, Idaho is the only place it is legal statewide.

Published on June 11, 2021 04:00

June 10, 2021

Idaho's Favorite Exotic?

Countless species have been introduced into Idaho accidently and intentionally, often to the detriment of native plants and animals. Exotic species can be an enormous problem because they often nudge out existing flora and fauna, taking over a niche and exploiting some advantage to become a nuisance if not a threat. At the top of the list in Idaho is probably cheatgrass. We are aware of this today and go to great lengths to fight invasive species, such as zebra mussels. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game is one of several state agencies engaged in such fights.

It wasn’t always so.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Fish and Game—a much looser, less scientific entity then—went to some trouble to import an exotic species that is so common today that many people likely think it is native: the ring-necked pheasant, a native of Asia.

Pheasants have been in the U.S. since about 1773, though they didn’t really become common until the 1800s in the East. The birds with their extravagant tail feathers came West in 1881, but not under their own power. They were imported first into Oregon.

Idaho’s state game warden hatched a plan to hatch some pheasants in 1907, hoping to provide sport for hunters. There were likely a few pheasants in Idaho before that, perhaps moving in from Washington and Oregon. They may have also escaped or been set free from amateur breeding operations. A Lewiston hunting club imported some for the sport of its members. Farmers could buy pheasant eggs and read about how to raise pheasants in the Gem State Rural.

Other states had set up hatchery programs, so Idaho had some clues as to how to do it. Deputy State Game Warden B.T. Livingston set out on January 21 for Corvallis, Oregon to pick up 225 English and China pheasants. Forty pens had been set up on leased land on the G.A. Stevens farm just west of Boise. Each pen was 16 feet square and 6 ½ feet high. Wire netting kept the birds in while a few boards provided shelter from the sun and rain. To raise more chicks, pheasant eggs were gathered once they appeared, and placed under regular chickens to hatch.

To avoid unnecessary ruffling of feathers, the Oregon Shortline train carrying the cargo of exotic birds made a special stop at the Stevens farm to unload its cargo rather than offloading them at the depot and hauling them back by wagon.

Even with careful care the birds didn’t do very well that first year. The state hired a pheasant specialist to oversee the breeding operation. Additional hatcheries popped up across Southern Idaho in subsequent years to increase the release of the birds into the wild.

By 1910 pheasants were thriving and breeding rapidly. They were touted as a benefit to farmers because of the thousands of insects they eat. In 1911, “bird fancier” Roland Voddard, was travelling the state talking up pheasants to farmers. Several started raising and releasing them into their fields to go after grasshoppers, particularly. Voddard was quoted in the Idaho Statesman as saying, “The pheasants will form a mighty good advance army for the work in this state as they have elsewhere. They are not a crop-destroying bird and will not dig up the grain as will chickens if they are left in the fields.”

Well, that was one opinion. By 1918, the Farm Bureau had declared war on pheasants. Farmers in the Magic Valley had come to believe that the pest-eating function of pheasants was negligible, while their love of grain was a real problem. It was said that mother pheasants had a strategy of flying up through the stands of grain, knocking against the seeds with their wings, and scattering it to be consumed by their chicks.

That same year the Twin Falls Weekly News published a recipe to make a coal tar and linseed oil mix with which farmers could coat corn. This was said to make it unpalatable to pheasants and not affect its ability to germinate.

At the time, there was no hunting season on the birds. They were protected so that their population would increase. The Farm Bureau lobbied to get a season established to help control the pesky birds. Allowing hunters to shoot them had always been the plan, so hunting seasons for pheasants began.

Pheasants remain a popular game bird today. Fish and Game releases thousands of them into the wild every year. In 2020 they released 34,000 birds.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

It wasn’t always so.

In the early part of the 20th Century, Fish and Game—a much looser, less scientific entity then—went to some trouble to import an exotic species that is so common today that many people likely think it is native: the ring-necked pheasant, a native of Asia.

Pheasants have been in the U.S. since about 1773, though they didn’t really become common until the 1800s in the East. The birds with their extravagant tail feathers came West in 1881, but not under their own power. They were imported first into Oregon.

Idaho’s state game warden hatched a plan to hatch some pheasants in 1907, hoping to provide sport for hunters. There were likely a few pheasants in Idaho before that, perhaps moving in from Washington and Oregon. They may have also escaped or been set free from amateur breeding operations. A Lewiston hunting club imported some for the sport of its members. Farmers could buy pheasant eggs and read about how to raise pheasants in the Gem State Rural.

Other states had set up hatchery programs, so Idaho had some clues as to how to do it. Deputy State Game Warden B.T. Livingston set out on January 21 for Corvallis, Oregon to pick up 225 English and China pheasants. Forty pens had been set up on leased land on the G.A. Stevens farm just west of Boise. Each pen was 16 feet square and 6 ½ feet high. Wire netting kept the birds in while a few boards provided shelter from the sun and rain. To raise more chicks, pheasant eggs were gathered once they appeared, and placed under regular chickens to hatch.

To avoid unnecessary ruffling of feathers, the Oregon Shortline train carrying the cargo of exotic birds made a special stop at the Stevens farm to unload its cargo rather than offloading them at the depot and hauling them back by wagon.

Even with careful care the birds didn’t do very well that first year. The state hired a pheasant specialist to oversee the breeding operation. Additional hatcheries popped up across Southern Idaho in subsequent years to increase the release of the birds into the wild.

By 1910 pheasants were thriving and breeding rapidly. They were touted as a benefit to farmers because of the thousands of insects they eat. In 1911, “bird fancier” Roland Voddard, was travelling the state talking up pheasants to farmers. Several started raising and releasing them into their fields to go after grasshoppers, particularly. Voddard was quoted in the Idaho Statesman as saying, “The pheasants will form a mighty good advance army for the work in this state as they have elsewhere. They are not a crop-destroying bird and will not dig up the grain as will chickens if they are left in the fields.”

Well, that was one opinion. By 1918, the Farm Bureau had declared war on pheasants. Farmers in the Magic Valley had come to believe that the pest-eating function of pheasants was negligible, while their love of grain was a real problem. It was said that mother pheasants had a strategy of flying up through the stands of grain, knocking against the seeds with their wings, and scattering it to be consumed by their chicks.

That same year the Twin Falls Weekly News published a recipe to make a coal tar and linseed oil mix with which farmers could coat corn. This was said to make it unpalatable to pheasants and not affect its ability to germinate.

At the time, there was no hunting season on the birds. They were protected so that their population would increase. The Farm Bureau lobbied to get a season established to help control the pesky birds. Allowing hunters to shoot them had always been the plan, so hunting seasons for pheasants began.

Pheasants remain a popular game bird today. Fish and Game releases thousands of them into the wild every year. In 2020 they released 34,000 birds.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

In 1909, the third year of the pheasant stocking program in Idaho, the state imported 1,000 birds in a special train car. Idaho Fish and Game Photo.

Published on June 10, 2021 04:00

June 9, 2021

Elias Davidson Pierce, that Jerk

Randy Stapilus’ book

Speaking Ill of the Dead, Jerks in Idaho History

is an interesting read. He has a chapter on Elias Davidson Pierce. Pierce’s jerkiness, in Randy’s telling, comes from his complete disregard for both advice from authorities and reservation boundaries. I recommend you read the book to find out more.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Today, I’m going to pull out just a few tidbits that I found interesting.

Pierce was the first man to name a town in Idaho—or what would be Idaho—after himself. Others with little modesty would follow. His town came along in 1860 when he set it up on the Nez Perce Reservation to service miners. The town was called… Wait, have you been paying attention at all?

So, Pierce, Idaho grew up fast. Thousands came to mine gold and by 1862 it was the county seat of Shoshone County. Not the Shoshone County we know and love today, but Shoshone County, Washington Territory. Idaho Territory was still a year away. Even so, when they built the courthouse it would, upon Idaho gaining territorial status, become the territory’s first government building. It remains the oldest government building in Idaho (photo).

Pierce glittered like gold in a pan and for about that long. By 1863 the population dropped from several thousand to about 500, because gold glittered somewhere else, drawing miners away. That’s about the population of Pierce today.

Published on June 09, 2021 04:00