Rick Just's Blog, page 119

July 28, 2021

Aspirational Architecture

Forgive me, please, as I drift into a mild editorial today about public architecture.

School buildings were once a source of great community pride. This was displayed in their aspirational architecture, such as that of Boise High School (photo). The school people know today was built in phases, beginning in 1908. It was the work of Idaho architects John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel, who would also design the Idaho statehouse. Boise High is designed in the neo-classical revival style. One of the details that one might consider aspirational is the representation of Plato in the frieze on the portico roof at the entrance, held aloft by soaring columns.

Compare this to almost any high school built in the past 30 years. You’ll more often find a design that would work as well for a prison, with concrete and cinder block walls and small windows if windows are included at all. There is an industrial feel to these schools.

The aspirations of the community were sometimes reflected in school names. In Boise three early schools were named for poets, Whittier, Lowell, and Longfellow. Today names like that are more often found in the themed streets of subdivisions.

Building a school with memorable architecture would probably be impossible today, given the resistance to the additional cost. I understand why communities, arguably, choose to invest more in education itself, rather than the buildings that house the students. I wonder, though, if we are missing something important in the educational environment, a sense of wonder and of continuity with the past.

Since we are unlikely to build something today with character, I encourage communities that still can to save their iconic old school buildings whenever possible.

School buildings were once a source of great community pride. This was displayed in their aspirational architecture, such as that of Boise High School (photo). The school people know today was built in phases, beginning in 1908. It was the work of Idaho architects John E. Tourtellotte and Charles F. Hummel, who would also design the Idaho statehouse. Boise High is designed in the neo-classical revival style. One of the details that one might consider aspirational is the representation of Plato in the frieze on the portico roof at the entrance, held aloft by soaring columns.

Compare this to almost any high school built in the past 30 years. You’ll more often find a design that would work as well for a prison, with concrete and cinder block walls and small windows if windows are included at all. There is an industrial feel to these schools.

The aspirations of the community were sometimes reflected in school names. In Boise three early schools were named for poets, Whittier, Lowell, and Longfellow. Today names like that are more often found in the themed streets of subdivisions.

Building a school with memorable architecture would probably be impossible today, given the resistance to the additional cost. I understand why communities, arguably, choose to invest more in education itself, rather than the buildings that house the students. I wonder, though, if we are missing something important in the educational environment, a sense of wonder and of continuity with the past.

Since we are unlikely to build something today with character, I encourage communities that still can to save their iconic old school buildings whenever possible.

Published on July 28, 2021 04:00

July 27, 2021

Shoup at Sand Creek

History is full of imperfect men. How could it be otherwise?

Idaho’s last territorial governor and the first governor of the State of Idaho was George L. Shoup. He didn’t serve long as Idaho’s governor. The Idaho Legislature elected him to the US Senate just a few weeks after he had been appointed governor. He served in the senate for ten years.

There is much one can say about Shoup that is positive. He was a strong force in shaping Idaho in its early days. Strong enough that he is honored in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol. Each state gets only two statues. Idaho chose Shoup (photo) and Senator William E. Borah for that honor.

Among his many business and political accomplishments is one that is a mere footnote in his biography, but it is one that has always troubled me. Col. George L. Shoup was a key leader of what is most often referred to today as the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the Battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of Colorado U.S. Volunteer Cavalry attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70–163 Native Americans, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service.

It is too complex an issue for a short post to examine all sides of the story and better understand the motives of those involved. To his credit, many times in his later life Shoup showed a willingness to work with Native Americans and he supported fair treatment for them. It is also worth noting that two troop commanders, Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, refused to have their soldiers engage. They are seen as heroes today by many.

Idaho’s last territorial governor and the first governor of the State of Idaho was George L. Shoup. He didn’t serve long as Idaho’s governor. The Idaho Legislature elected him to the US Senate just a few weeks after he had been appointed governor. He served in the senate for ten years.

There is much one can say about Shoup that is positive. He was a strong force in shaping Idaho in its early days. Strong enough that he is honored in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol. Each state gets only two statues. Idaho chose Shoup (photo) and Senator William E. Borah for that honor.

Among his many business and political accomplishments is one that is a mere footnote in his biography, but it is one that has always troubled me. Col. George L. Shoup was a key leader of what is most often referred to today as the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the Battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of Colorado U.S. Volunteer Cavalry attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70–163 Native Americans, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service.

It is too complex an issue for a short post to examine all sides of the story and better understand the motives of those involved. To his credit, many times in his later life Shoup showed a willingness to work with Native Americans and he supported fair treatment for them. It is also worth noting that two troop commanders, Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, refused to have their soldiers engage. They are seen as heroes today by many.

Published on July 27, 2021 04:00

July 26, 2021

The Lemp Triangle

Boise has played the waiting game several times in its history. Citizens have waited for a promised project for decades while staring into a hole or across a dusty gravel parking lot.

The Hole at 8th and Main gaped there on the verge of great things for more than 20 years. Zions Bank opened its new tower in 2014, finally fitting into the footprint of the old Eastman Building that burned in 1987. The gravel parking lot that covered the block where the Boise Convention Center and other downtown amenities now sit was a point of conjecture for years. Ideas bounced around until the proposal to put a squat, concrete shopping mall that would be as enticing as a prison on the site invigorated enough opposition to rethink and renew downtown.

But those projects were just blips compared with the field of dreams known as the Lemp Triangle. Dreamers started envisioning its future in 1870 and continued plotting until 1937, when something important finally got built.

The Lemp Triangle is an accident of platting. When city fathers drew up the first maps of Boise, they platted it so that streets would run roughly parallel to the Boise River. That was just a convenient way to layout a town that might not be around very long. As the City survived and grew, developers of new additions mapped streets that ran to the points of a compass. Fitting the new additions to the original town plat created some odd-shaped properties. One became known as the Lemp Triangle in the North End, bounded today by W Resseguie to the north, N 13th to the east, W Fort to the south, and N 15th to the west. Clever readers may now be asking themselves why a triangle has four sides. The answer is that the property is a triangle with the western tip cut off. "Lemp Sort-of-a Triangle" just doesn't have the verve of the shorter name.

John Lemp, brewer, businessman, and local politician, began planning to sell lots in his new Lemp Addition north of the City in 1891. Mayor James Pinney saw the wisdom in snugging up the Lemp Addition to the original plat for Boise, so he deeded what became the Triangle to Lemp for $1.

Then came the tricky part. Did Boise own the land in the first place? In 1867 Boise had petitioned the US Department of the Interior for a townsite patent. The City was expecting a patent for 410 acres, the size of the original plat. Instead, they received a patent for an extra 32 acres, which included the Lemp Triangle. Maybe.

Imagine John Lemp's surprise when in August 1892, J.C. Pence, another local politician and businessman, began constructing a house on the Lemp Triangle. Lemp offered to pay Pence a small sum to remove the house. Pence declined, claiming that he owned the land. So on August 18, Lemp sent a group of armed men to demolish the house. They piled the resulting debris in the street, then tore up the foundation.

This dispute began a series of lawsuits that kept the property tied up for the next 25 years. At various times it became clear that Pence owned the property or that Lemp owned the property, or that the City owned the property. There were wins and losses enough to keep all parties confused. When the last, really, truly, absolutely final decision came down, the Idaho Supreme Court ruled that Lemp owned the property through adverse possession. Unfortunately, Lemp had been dead four years by that time, so he didn't get a chance to celebrate.

With ownership determined, the Lemp estate began advertising lots for sale in the Lemp Triangle. But remember those dreams and visions that had been bouncing around? Citizens had talked up a public park on the site for years. They dreamed about a playground for kids and a baseball field. At one point, when the City was temporarily confident it owned the property, voters narrowly turned down a proposal to make it a park.

In 1922 the Lemp estate came close to making the park dreams come true when it offered the city Camel's Back and the Lemp Triangle for the bargain price of $35,000. One stipulation was that any park built in the Triangle would be called John Lemp Park. The City mulled that over for a while. Maybe too long.

The Boise School Board finally put all disputes and dreams to rest when in 1925, they purchased the Triangle for $22,500. But, true to the site's history, it was another dozen years before anything happened there. North Junior High, designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, was built in 1937.

The school, lauded for its art deco design, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. The Lemp Triangle itself might have qualified without the beautiful public building given the long, sordid history of nothing happening there.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

The Hole at 8th and Main gaped there on the verge of great things for more than 20 years. Zions Bank opened its new tower in 2014, finally fitting into the footprint of the old Eastman Building that burned in 1987. The gravel parking lot that covered the block where the Boise Convention Center and other downtown amenities now sit was a point of conjecture for years. Ideas bounced around until the proposal to put a squat, concrete shopping mall that would be as enticing as a prison on the site invigorated enough opposition to rethink and renew downtown.

But those projects were just blips compared with the field of dreams known as the Lemp Triangle. Dreamers started envisioning its future in 1870 and continued plotting until 1937, when something important finally got built.

The Lemp Triangle is an accident of platting. When city fathers drew up the first maps of Boise, they platted it so that streets would run roughly parallel to the Boise River. That was just a convenient way to layout a town that might not be around very long. As the City survived and grew, developers of new additions mapped streets that ran to the points of a compass. Fitting the new additions to the original town plat created some odd-shaped properties. One became known as the Lemp Triangle in the North End, bounded today by W Resseguie to the north, N 13th to the east, W Fort to the south, and N 15th to the west. Clever readers may now be asking themselves why a triangle has four sides. The answer is that the property is a triangle with the western tip cut off. "Lemp Sort-of-a Triangle" just doesn't have the verve of the shorter name.

John Lemp, brewer, businessman, and local politician, began planning to sell lots in his new Lemp Addition north of the City in 1891. Mayor James Pinney saw the wisdom in snugging up the Lemp Addition to the original plat for Boise, so he deeded what became the Triangle to Lemp for $1.

Then came the tricky part. Did Boise own the land in the first place? In 1867 Boise had petitioned the US Department of the Interior for a townsite patent. The City was expecting a patent for 410 acres, the size of the original plat. Instead, they received a patent for an extra 32 acres, which included the Lemp Triangle. Maybe.

Imagine John Lemp's surprise when in August 1892, J.C. Pence, another local politician and businessman, began constructing a house on the Lemp Triangle. Lemp offered to pay Pence a small sum to remove the house. Pence declined, claiming that he owned the land. So on August 18, Lemp sent a group of armed men to demolish the house. They piled the resulting debris in the street, then tore up the foundation.

This dispute began a series of lawsuits that kept the property tied up for the next 25 years. At various times it became clear that Pence owned the property or that Lemp owned the property, or that the City owned the property. There were wins and losses enough to keep all parties confused. When the last, really, truly, absolutely final decision came down, the Idaho Supreme Court ruled that Lemp owned the property through adverse possession. Unfortunately, Lemp had been dead four years by that time, so he didn't get a chance to celebrate.

With ownership determined, the Lemp estate began advertising lots for sale in the Lemp Triangle. But remember those dreams and visions that had been bouncing around? Citizens had talked up a public park on the site for years. They dreamed about a playground for kids and a baseball field. At one point, when the City was temporarily confident it owned the property, voters narrowly turned down a proposal to make it a park.

In 1922 the Lemp estate came close to making the park dreams come true when it offered the city Camel's Back and the Lemp Triangle for the bargain price of $35,000. One stipulation was that any park built in the Triangle would be called John Lemp Park. The City mulled that over for a while. Maybe too long.

The Boise School Board finally put all disputes and dreams to rest when in 1925, they purchased the Triangle for $22,500. But, true to the site's history, it was another dozen years before anything happened there. North Junior High, designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, was built in 1937.

The school, lauded for its art deco design, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. The Lemp Triangle itself might have qualified without the beautiful public building given the long, sordid history of nothing happening there.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

North Junior High is built on land that was long contested, the Lemp Triangle.

Published on July 26, 2021 05:08

July 25, 2021

That Horseshoe Town

Time for another in our series called Idaho Then and Now.

Utopian communities were common in 19th Century America. The still new country attracted people who envisioned a perfect society.

One such community was New Plymouth, Idaho. William E. Smythe founded the New Plymouth Society of Chicago with aim of building a planned community in Idaho’s Payette River Valley. Unlike some utopian community, this one wasn’t based on religious or moral principles but rather on planning and irrigation.

On April 17, 1885 the Idaho Daily Statesman carried a story that quoted Smythe. “Each colonist will purchase 20 acres of irrigated land and 20 shares of stock in the Plymouth company,” Smythe said. “He will also be entitled to an acre in the central area set apart for the village site if he will build a house upon it and make his home there.”

The town itself was platted out in a horseshoe shape with the open end of the horseshoe facing north toward the Payette River (Google Earth image below). Shareholders’ farms and orchards would all be within two or three miles of town.

The paper quoted Smythe, “There is to be nothing communistic about this New Plymouth. There is to be very little co-operation even, in the technical sense. The only property which is to be owned in common is the town hall, which is to be modeled after the Idaho building at the World’s Fair.” The fair had been held in Chicago in 1893. The community would have a library and an electric lighting plant.

The town was incorporated in February, 1896. It started out with a couple hundred residents, each with at least $1,000 in cash to their name, as was required by the colony. Today it’s population is about 1,500.

The shape of the town is about the only clue left about its origins. Citizens call it the “World’s Biggest Horseshoe.”

Planned communities today in Idaho tend to come in a couple of forms. The first type, not unlike New Plymouth, is built with an eye on planned amenities. Hidden Springs and Avimor near Boise and Eagle, respectively, are examples. The other type of planned community that we hear about involves a belief that some form of political or natural disaster is due. These are the survivalists who are looking for someplace to ride out the storm. The redoubt movement is an example.

Utopian communities were common in 19th Century America. The still new country attracted people who envisioned a perfect society.

One such community was New Plymouth, Idaho. William E. Smythe founded the New Plymouth Society of Chicago with aim of building a planned community in Idaho’s Payette River Valley. Unlike some utopian community, this one wasn’t based on religious or moral principles but rather on planning and irrigation.

On April 17, 1885 the Idaho Daily Statesman carried a story that quoted Smythe. “Each colonist will purchase 20 acres of irrigated land and 20 shares of stock in the Plymouth company,” Smythe said. “He will also be entitled to an acre in the central area set apart for the village site if he will build a house upon it and make his home there.”

The town itself was platted out in a horseshoe shape with the open end of the horseshoe facing north toward the Payette River (Google Earth image below). Shareholders’ farms and orchards would all be within two or three miles of town.

The paper quoted Smythe, “There is to be nothing communistic about this New Plymouth. There is to be very little co-operation even, in the technical sense. The only property which is to be owned in common is the town hall, which is to be modeled after the Idaho building at the World’s Fair.” The fair had been held in Chicago in 1893. The community would have a library and an electric lighting plant.

The town was incorporated in February, 1896. It started out with a couple hundred residents, each with at least $1,000 in cash to their name, as was required by the colony. Today it’s population is about 1,500.

The shape of the town is about the only clue left about its origins. Citizens call it the “World’s Biggest Horseshoe.”

Planned communities today in Idaho tend to come in a couple of forms. The first type, not unlike New Plymouth, is built with an eye on planned amenities. Hidden Springs and Avimor near Boise and Eagle, respectively, are examples. The other type of planned community that we hear about involves a belief that some form of political or natural disaster is due. These are the survivalists who are looking for someplace to ride out the storm. The redoubt movement is an example.

Published on July 25, 2021 04:00

July 24, 2021

Spudnik

Okay, what would YOU call your potato equipment manufacturing business? If you were one of the Hobbs brothers who started their business in a potato cellar northwest of Blackfoot, you’d call it Spudnik. It was 1958. Get it? Russian satellite?

Carl and Leo Hobbs designed and developed the Spudnik Scooper. The company went on to develop harvesters, conveyors, planters, self-unloading truck beds and much other potato-oriented equipment. In 2001 they entered into a joint partnership with the Grimme Group of companies, headquartered in Damme, Germany, which is the largest potato equipment manufacturer in the world.

Spudnik is still headquartered in Blackfoot, the “Potato Capital of the World,” if you didn’t know. The photo is of their downtown Blackfoot office in 1960.

Carl and Leo Hobbs designed and developed the Spudnik Scooper. The company went on to develop harvesters, conveyors, planters, self-unloading truck beds and much other potato-oriented equipment. In 2001 they entered into a joint partnership with the Grimme Group of companies, headquartered in Damme, Germany, which is the largest potato equipment manufacturer in the world.

Spudnik is still headquartered in Blackfoot, the “Potato Capital of the World,” if you didn’t know. The photo is of their downtown Blackfoot office in 1960.

Published on July 24, 2021 04:00

July 23, 2021

Platt Gardens

I was working on a story recently that involved plats in Boise. At the same time I stumbled on a familiar name, Platt Garden. I wondered if there was a connection between that name and platting in Boise. There wasn’t.

Platt Gardens, according to the City of Boise website, was designed by Spanish landscape architect Ricardo Espino to grace the grounds of the Boise Train Depot. Union Pacific built the gardens which feature a winding walk, benches, ponds, a monument of volcanic rock and a welcoming display of greenery in 1927.

The Depot and Platt Gardens were donated to the City of Boise by Union Pacific in 1982. The gardens were named for Howard V. Platt who was the general manager of the original Oregon Short Line Railroad.

Platt Gardens, according to the City of Boise website, was designed by Spanish landscape architect Ricardo Espino to grace the grounds of the Boise Train Depot. Union Pacific built the gardens which feature a winding walk, benches, ponds, a monument of volcanic rock and a welcoming display of greenery in 1927.

The Depot and Platt Gardens were donated to the City of Boise by Union Pacific in 1982. The gardens were named for Howard V. Platt who was the general manager of the original Oregon Short Line Railroad.

Published on July 23, 2021 04:00

July 22, 2021

Who's in Charge of Naming Monsters?

No self-respecting lake monster should go without a name. At least, that’s what A. Boon McCallum, editor and publisher of the Payette Lakes Star thought.

Sightings of some sort of creature that seemed out of place in Payette Lake had been going on for years when the newspaper in McCall decided to run a contest, in 1954, to give the poor beast a name. More than 200 people entered the contest. The suggestions ranged from the pseudo-scientific to variations on monster names. They included:

Boon

Fantasy

Nobby Dick

Humpy

Watzit

McFlash

High Ho

Peekaboo

Snorky

Neptune Ned

…and on and on. The winner, as you may know, was Sharlie. Le Isle Hennefer Tury of Springfield, Virginia walked away with the $40 prize for that one. Lest Idahoans grump too much about an out-of-stater winning the contest, it was pointed out that she had at one time lived in Twin Falls.

I confess to having my own “Sharlie” sighting once while standing atop Porcupine Point in Ponderosa State Park. With no boats in site for miles the water below in The Narrows started churning. It continued to churn for about two minutes. There was no creepy music accompanying the phenomenon, so I just chalked it up to space aliens.

Sightings of some sort of creature that seemed out of place in Payette Lake had been going on for years when the newspaper in McCall decided to run a contest, in 1954, to give the poor beast a name. More than 200 people entered the contest. The suggestions ranged from the pseudo-scientific to variations on monster names. They included:

Boon

Fantasy

Nobby Dick

Humpy

Watzit

McFlash

High Ho

Peekaboo

Snorky

Neptune Ned

…and on and on. The winner, as you may know, was Sharlie. Le Isle Hennefer Tury of Springfield, Virginia walked away with the $40 prize for that one. Lest Idahoans grump too much about an out-of-stater winning the contest, it was pointed out that she had at one time lived in Twin Falls.

I confess to having my own “Sharlie” sighting once while standing atop Porcupine Point in Ponderosa State Park. With no boats in site for miles the water below in The Narrows started churning. It continued to churn for about two minutes. There was no creepy music accompanying the phenomenon, so I just chalked it up to space aliens.

Published on July 22, 2021 04:00

July 21, 2021

A 1909 Look at the Future

Prognostication in print eventually tends to make the prognosticator look foolish. Witness the regular predictions about the fantastic future filled with flying cars, jet packs, and moving sidewalks common in the early Twentieth Century.

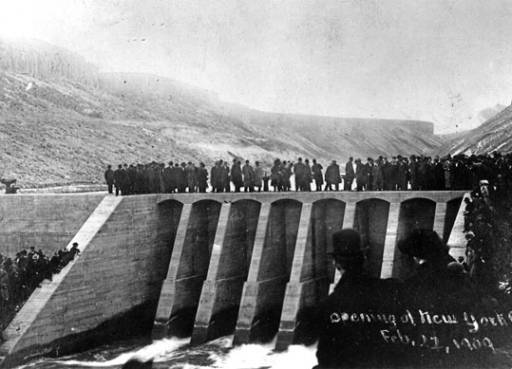

In 1909 one prognosticator at the Idaho Statesman got it right helped, perhaps, by his neglecting to establish a timeline for his predictions. The day following the dedication of Treasure Valley’s New York Canal on February, 22 1909, an article appeared titled “Power Behind the Dam.”

“Upon even the most thoughtless the real importance of the work, completion of which was yesterday celebrated will be forced to mind when thousands of acres of additional land is brought under cultivation, when Boise bounds to 150,000 population; when farms supplant great stretches of barren land and the swaddling clothes of towns in this part of the state are tossed into the rubbish heap in exchange for municipal togs.”

Boise’s population in 1909 was about 17,000, so a city of 150,000 probably seemed ludicrous. It would hit that mark in the early 1990s and today is closer to 250,000.

The progression from desert to farm to town to city was also correct. Eagle with a Hilton? Who’d have thought that in 1909 or even 1979?

Diversion Dam also supplied electricity for the valley for many years, as well as irrigation water for farmland that in more recent decades has grown into sprawling housing developments.

The photo of the dedication of New York Canal diversion is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive.

In 1909 one prognosticator at the Idaho Statesman got it right helped, perhaps, by his neglecting to establish a timeline for his predictions. The day following the dedication of Treasure Valley’s New York Canal on February, 22 1909, an article appeared titled “Power Behind the Dam.”

“Upon even the most thoughtless the real importance of the work, completion of which was yesterday celebrated will be forced to mind when thousands of acres of additional land is brought under cultivation, when Boise bounds to 150,000 population; when farms supplant great stretches of barren land and the swaddling clothes of towns in this part of the state are tossed into the rubbish heap in exchange for municipal togs.”

Boise’s population in 1909 was about 17,000, so a city of 150,000 probably seemed ludicrous. It would hit that mark in the early 1990s and today is closer to 250,000.

The progression from desert to farm to town to city was also correct. Eagle with a Hilton? Who’d have thought that in 1909 or even 1979?

Diversion Dam also supplied electricity for the valley for many years, as well as irrigation water for farmland that in more recent decades has grown into sprawling housing developments.

The photo of the dedication of New York Canal diversion is courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital archive.

Published on July 21, 2021 04:00

July 20, 2021

KIDO Announcer Finds Fame

Why would you ever change your name when you had such a good one in Cletus Leo Schwitters? Baffling. Yet, Schwitters went by his air name Clete Lee when he was working as a disk jockey on Boise’s KIDO in the late 30s and early 40s.

Lee was the game show host for the Preferred Stock Spelling Bee in 1940. Preferred Stock was a manufacturer of canned foods. The show featured a live studio audience and a set that included a “man in the moon” wearing a cone hat behind the host. When the cartoon character’s eyes lit up, the audience was encouraged to applaud.

The popular radio announcer did a stint in the army after the war. When he got out, he tried his luck in Hollywood. For many years Boiseans were proud of their “hometown” boy (he was actually born in Illinois) as he went on to gain a measure of fame as actor Byron Keith.

Keith appeared in in the 1946 movie The Stranger, alongside Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, and Orson Welles, with Welles directing. He was in several other movies, and had a recurring role as police lieutenant Roy Gilmore in the TV’s 77 Sunset Strip. He may be best known for his ten episodes in the original Batman TV series as Mayor Linseed.

Byron Keith/Clete Lee/Cletus Leo Schwitters passed away at age 78 in Los Angeles in 1996. L. to R. : Richard Long, Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, Martha Wentworth, Orson Welles, Philip Merivale, Byron Keith, and unknown actress in

The Stranger

(1946).

L. to R. : Richard Long, Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, Martha Wentworth, Orson Welles, Philip Merivale, Byron Keith, and unknown actress in

The Stranger

(1946).

Lee was the game show host for the Preferred Stock Spelling Bee in 1940. Preferred Stock was a manufacturer of canned foods. The show featured a live studio audience and a set that included a “man in the moon” wearing a cone hat behind the host. When the cartoon character’s eyes lit up, the audience was encouraged to applaud.

The popular radio announcer did a stint in the army after the war. When he got out, he tried his luck in Hollywood. For many years Boiseans were proud of their “hometown” boy (he was actually born in Illinois) as he went on to gain a measure of fame as actor Byron Keith.

Keith appeared in in the 1946 movie The Stranger, alongside Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, and Orson Welles, with Welles directing. He was in several other movies, and had a recurring role as police lieutenant Roy Gilmore in the TV’s 77 Sunset Strip. He may be best known for his ten episodes in the original Batman TV series as Mayor Linseed.

Byron Keith/Clete Lee/Cletus Leo Schwitters passed away at age 78 in Los Angeles in 1996.

L. to R. : Richard Long, Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, Martha Wentworth, Orson Welles, Philip Merivale, Byron Keith, and unknown actress in

The Stranger

(1946).

L. to R. : Richard Long, Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, Martha Wentworth, Orson Welles, Philip Merivale, Byron Keith, and unknown actress in

The Stranger

(1946).

Published on July 20, 2021 04:00

July 19, 2021

Glen Taylor, a Man of Many Talents

Once you’ve been a member of the U.S. Senate and a vice presidential candidate, what do you do with the rest of your life? The answer, for Glen Taylor, was to make hair pieces.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players. When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

Glen Taylor and his band.

Glen Taylor and his band.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players. When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

Glen Taylor and his band.

Glen Taylor and his band.

Published on July 19, 2021 04:00