Rick Just's Blog, page 116

August 27, 2021

News from Presto

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Descendants of Nels and Emma Just have been involved with newspapers directly and in tangential ways over the years.

Nels Just, entrepreneur that he was, invested in The Times, a short-lived newspaper in Eagle Rock. Agnes Just Reid was part owner of the Blackfoot Optimist for a couple of years before it went bust. I had negotiated a deal to buy the Shelley Pioneer in the 1970s but backed out at the signing when the owner decided he needed more money after all.

The most prolific writer for newspapers was Agnes Just Reid. She wrote her column, “Here’s a Thought,” for more than 40 years for the Blackfoot newspaper. She was also the Presto correspondent for many years for that paper. Many of her stories were picked up by other papers around the state and in Utah. Presto was what the tiny farming community along the Blackfoot River is called. It is named after Presto Burrell, the first settler in the area.

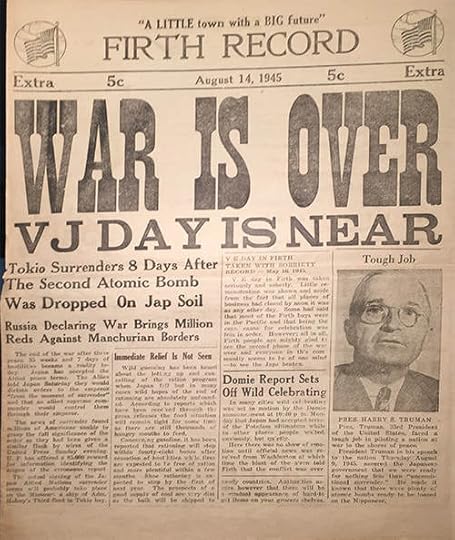

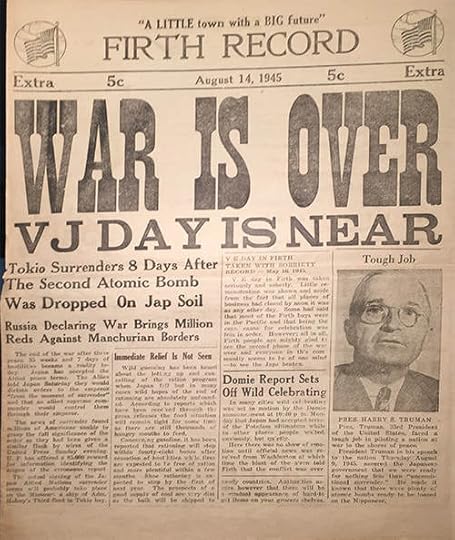

Agnes’ son Doug Reid was a stringer for the Salt Lake Tribune for several years. From 1944 to 1950, Doug, Agnes, and Clarice Mattson, all family members, wrote for the Firth Record. Doug was the sports editor and did just about anything else that came his way (see photo).

Iris Just Adamson, my mother, had a column in the Shelley Pioneer for many years and regularly wrote for farm magazines in the region.

I wrote a column on Idaho History for the Blackfoot Morning News in the waning months of its existence and still write one for the Idaho Press. While serving in the Marine Corps, I was the editor of the New River Air Station base newspaper, Rotovue.

Many family members were surprised to learn, recently, that Agnes Just Reid published a little community newspaper in 1908 called the Presto Times. It wasn’t so surprising that young Agnes had been busy at her typewriter then. She always was. The surprising part was that we didn’t know there was another publication with Presto in its name. For 35 years, we’ve been putting out a family newsletter (now magazine) called Presto Press. I edit the magazine. Many issues are available digitally for those who are interested in reading them.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Descendants of Nels and Emma Just have been involved with newspapers directly and in tangential ways over the years.

Nels Just, entrepreneur that he was, invested in The Times, a short-lived newspaper in Eagle Rock. Agnes Just Reid was part owner of the Blackfoot Optimist for a couple of years before it went bust. I had negotiated a deal to buy the Shelley Pioneer in the 1970s but backed out at the signing when the owner decided he needed more money after all.

The most prolific writer for newspapers was Agnes Just Reid. She wrote her column, “Here’s a Thought,” for more than 40 years for the Blackfoot newspaper. She was also the Presto correspondent for many years for that paper. Many of her stories were picked up by other papers around the state and in Utah. Presto was what the tiny farming community along the Blackfoot River is called. It is named after Presto Burrell, the first settler in the area.

Agnes’ son Doug Reid was a stringer for the Salt Lake Tribune for several years. From 1944 to 1950, Doug, Agnes, and Clarice Mattson, all family members, wrote for the Firth Record. Doug was the sports editor and did just about anything else that came his way (see photo).

Iris Just Adamson, my mother, had a column in the Shelley Pioneer for many years and regularly wrote for farm magazines in the region.

I wrote a column on Idaho History for the Blackfoot Morning News in the waning months of its existence and still write one for the Idaho Press. While serving in the Marine Corps, I was the editor of the New River Air Station base newspaper, Rotovue.

Many family members were surprised to learn, recently, that Agnes Just Reid published a little community newspaper in 1908 called the Presto Times. It wasn’t so surprising that young Agnes had been busy at her typewriter then. She always was. The surprising part was that we didn’t know there was another publication with Presto in its name. For 35 years, we’ve been putting out a family newsletter (now magazine) called Presto Press. I edit the magazine. Many issues are available digitally for those who are interested in reading them.

Published on August 27, 2021 04:00

August 26, 2021

Not the Poet Laureate

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August

I was helping to produce an interpretive handout for use in the historic home once occupied by my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid when the subject of poet laureates came up. She was a well-known writer in the northwest when she was alive. A family member mentioned that she had been the poet laureate of Idaho. I didn’t think so, because it was the kind of thing I would remember. So, that sent me down a poet laureate path.

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

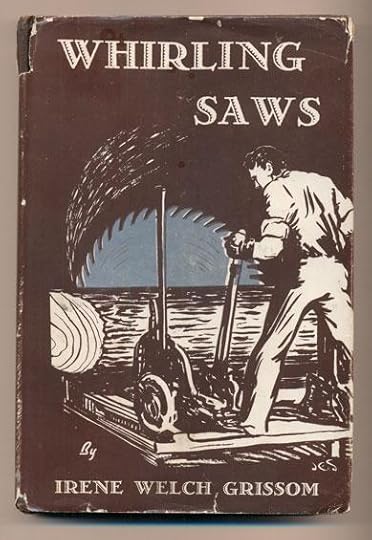

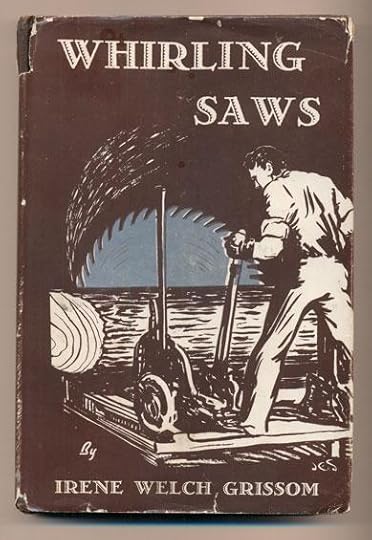

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to July 2021)

Lauren W. Westerfield (July 2021 to the present)

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August

I was helping to produce an interpretive handout for use in the historic home once occupied by my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid when the subject of poet laureates came up. She was a well-known writer in the northwest when she was alive. A family member mentioned that she had been the poet laureate of Idaho. I didn’t think so, because it was the kind of thing I would remember. So, that sent me down a poet laureate path.

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to July 2021)

Lauren W. Westerfield (July 2021 to the present)

Published on August 26, 2021 04:00

August 25, 2021

Letters and Letters Found

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

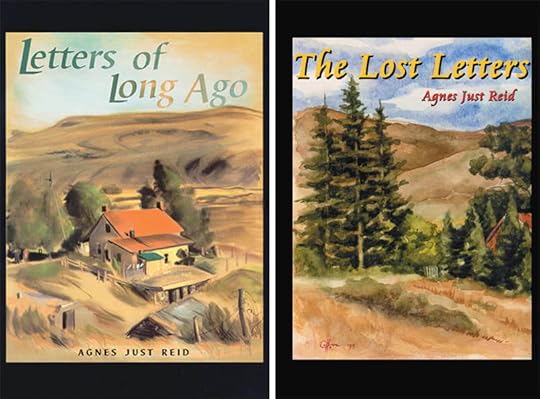

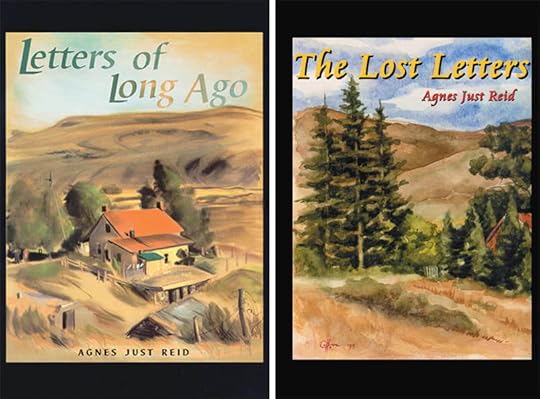

If you’ve been reading these posts the past few weeks, you’ve noticed several references to Letters of Long Ago by Agnes Just Reid. In addition, some posts used whole chapters of that book.

Agnes Just Reid was the only living daughter of Nels and Emma Just. She was my great aunt, and I was fortunate to know her quite well. Years ago, it occurred to me how young our family’s pioneer history is, even though our history in Idaho began the same year it became a territory. Agnes, who was born in 1886, could have met someone who knew George Washington. As far as I know, she did not, but it is another illustration of how young our country is.

Because of Agnes, the Just and Reid families are so aware of their history and why we are dedicated to keeping it alive.

Letters of Long Ago is a classic pioneer story that has endured for more than a century, finding new fans within the family and outside of it with each of its four printings in 1923, 1936, 1973, and 1997. Reid used letters as a literary device to tell the story of her mother, Emma Thompson Just, who came to Idaho in 1863. The letters Emma wrote to her father, George Thompson, had been lost. Their re-creation for the book was essentially the recording of an oral history.

Emma Thompson Just approved each of the “letters” as they came off the typewriter, so we have reasonable assurance of their accuracy so far as memory would allow.

A year after the death of Agnes Just Reid, her niece, Mabel Bennett Hutchinson, who had illustrated the original book, found a similar manuscript. Although much shorter than the original, it still features the simple yet powerful writing of the first, again using the device of letters from Emma to tell the story of her earlier life. This time the letters were written to her “Cousin Lucy.” They were published in a limited edition in 2000 for the first time as The Lost Letters, by Agnes Just Reid.

How well does this account in this manuscript tell the early story of Emma Thompson Just? It is questionable whether Emma ever saw this manuscript. She died November 8, 1923, before she ever got a chance to hold Letters of Long Ago in her hands. Did Agnes Just Reid write both manuscripts before her mother’s death, choosing to publish only the years from 1870 to 1891? I believe that is unlikely. Letters of Long Ago reads like a book complete unto itself from beginning to end, as does The Lost Letters. It is far more likely that Reid was encouraged by the first book’s success and set out to write another about her mother’s early life. Why it was never published is anyone’s guess. Perhaps the author did not think it was up to her standards. Maybe she thought it was simply too short. If her daughter wrote the manuscript after the death of Emma Thompson Just, it did not have the benefit of Emma’s review. Keeping that in mind, it is still an important record. Agnes Just Reid knew her mother, as well as any daughter could. She had access to letters and diaries that would help her fill in the blanks. Most of all, the book is believable because Emma was an uncommonly frank woman.

The Lost Letters completes Emma’s story. It is a story of agony and achievement, pride and pain. Emma speaks to us from across a century through her richly talented daughter when Idaho was barely an idea.

I’m pleased to announce that The Lost Letters is once again available to readers in book form and as an eBook from Amazon.

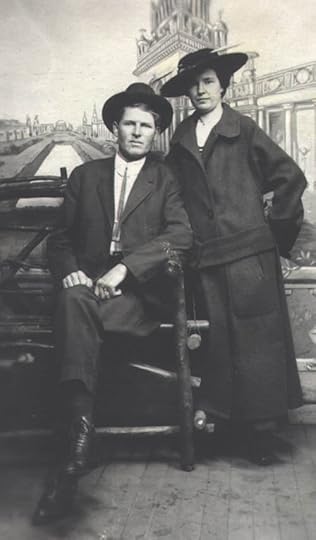

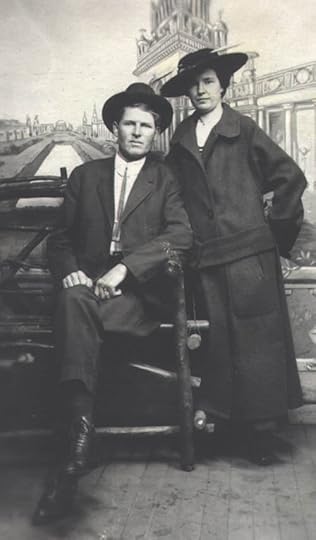

Bob Reid and Agnes Just Reid. This photo was taken in 1916, seven years before the publication of Letters of Long Ago.

Bob Reid and Agnes Just Reid. This photo was taken in 1916, seven years before the publication of Letters of Long Ago.  Both books by Agnes Just Reid are now available in paperback and as eBooks.

Both books by Agnes Just Reid are now available in paperback and as eBooks.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

If you’ve been reading these posts the past few weeks, you’ve noticed several references to Letters of Long Ago by Agnes Just Reid. In addition, some posts used whole chapters of that book.

Agnes Just Reid was the only living daughter of Nels and Emma Just. She was my great aunt, and I was fortunate to know her quite well. Years ago, it occurred to me how young our family’s pioneer history is, even though our history in Idaho began the same year it became a territory. Agnes, who was born in 1886, could have met someone who knew George Washington. As far as I know, she did not, but it is another illustration of how young our country is.

Because of Agnes, the Just and Reid families are so aware of their history and why we are dedicated to keeping it alive.

Letters of Long Ago is a classic pioneer story that has endured for more than a century, finding new fans within the family and outside of it with each of its four printings in 1923, 1936, 1973, and 1997. Reid used letters as a literary device to tell the story of her mother, Emma Thompson Just, who came to Idaho in 1863. The letters Emma wrote to her father, George Thompson, had been lost. Their re-creation for the book was essentially the recording of an oral history.

Emma Thompson Just approved each of the “letters” as they came off the typewriter, so we have reasonable assurance of their accuracy so far as memory would allow.

A year after the death of Agnes Just Reid, her niece, Mabel Bennett Hutchinson, who had illustrated the original book, found a similar manuscript. Although much shorter than the original, it still features the simple yet powerful writing of the first, again using the device of letters from Emma to tell the story of her earlier life. This time the letters were written to her “Cousin Lucy.” They were published in a limited edition in 2000 for the first time as The Lost Letters, by Agnes Just Reid.

How well does this account in this manuscript tell the early story of Emma Thompson Just? It is questionable whether Emma ever saw this manuscript. She died November 8, 1923, before she ever got a chance to hold Letters of Long Ago in her hands. Did Agnes Just Reid write both manuscripts before her mother’s death, choosing to publish only the years from 1870 to 1891? I believe that is unlikely. Letters of Long Ago reads like a book complete unto itself from beginning to end, as does The Lost Letters. It is far more likely that Reid was encouraged by the first book’s success and set out to write another about her mother’s early life. Why it was never published is anyone’s guess. Perhaps the author did not think it was up to her standards. Maybe she thought it was simply too short. If her daughter wrote the manuscript after the death of Emma Thompson Just, it did not have the benefit of Emma’s review. Keeping that in mind, it is still an important record. Agnes Just Reid knew her mother, as well as any daughter could. She had access to letters and diaries that would help her fill in the blanks. Most of all, the book is believable because Emma was an uncommonly frank woman.

The Lost Letters completes Emma’s story. It is a story of agony and achievement, pride and pain. Emma speaks to us from across a century through her richly talented daughter when Idaho was barely an idea.

I’m pleased to announce that The Lost Letters is once again available to readers in book form and as an eBook from Amazon.

Bob Reid and Agnes Just Reid. This photo was taken in 1916, seven years before the publication of Letters of Long Ago.

Bob Reid and Agnes Just Reid. This photo was taken in 1916, seven years before the publication of Letters of Long Ago.  Both books by Agnes Just Reid are now available in paperback and as eBooks.

Both books by Agnes Just Reid are now available in paperback and as eBooks.

Published on August 25, 2021 04:00

August 24, 2021

B.M. Bower's Friendship

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. Who can we claim as an Idaho writer? Must they be born here, as Ezra Pound was? He had not learned to write his name when he moved away from the state, never to return. How about Ernest Hemingway, who wasn’t born here but lived and wrote in the state?

Or, how about someone who never really took up residence here, but wrote two novels in Idaho? Discuss among yourselves, but that criteria allows me to write a little Idaho story about an author who was wildly popular at one time.

B.M. Bower wrote, by my count, 68 novels—many still in print—and over a dozen screenplays. She is often favorably compared with Zane Grey, one of her contemporaries.

She was born Bertha Muzzy in 1871. Her family moved from Minnesota to a dryland homestead near Great Falls, Montana in 1889. At age 19, she eloped with a homesteader cowboy named Clayton Bower, thus giving her the pen name she would use for the rest of her life. Rather than Bertha Muzzy Bower, she chose B.M. so that readers could assume she was a man.

She would marry three men, divorcing two of them, and teaching one, her second husband Bill Sinclair, how to write a Western novel. He wrote 15 of his own.

Bower wrote her novels from homes in Montana, Washington, and California. She wrote two of them in Idaho, on brief visits. The Good Indian was written while she visited the ranch home of David Bliss, for whom Bliss, Idaho is named.

Bower’s second Idaho book was called Ranch at the Wolverine . She pumped that one out during a stay of about two months in 1913 at the home of my Great Aunt Agnes Just Reid, best known for her book Letters of Long Ago . The Just/Reid family home is in the Blackfoot River Valley below Wolverine Canyon. Agnes and B.M. spent much of that summer riding horses, exploring the canyon, and often riding into Blackfoot, about 15 miles away.

B.M. Bower loved to write details into her books from personal experience. In September 1913 the War Bonnet Roundup would take place in Idaho Falls. There was to be a women’s saddle horse race, and Bower talked Agnes into riding the 18 miles to the Roundup and entering the race the next day.

Agnes Just Reid remembered it this way: “Bower wanted to ride in the race for the sensation of it. Dressed in our long, divided, skirts of corduroy, so the wind would not blow them and show our ankles, we raced our fat, old cattle horses around the track far behind the professionals. But we got our sensation and the dust.”

Ranch of the Wolverine and The Good Indian are still in print.

In our family archives we have a B.M. Bower manuscript with charred edges that survived a fire in the home of Agnes and Robert E. Reid. When I learned that, I thought we might have a rare, unpublished novel by Bower. Alas, the manuscript was not unique and the novel was among the dozens she published.

Bower passed away in 1940 at age 69. Her friend, Agnes Just Reid, passed away in 1976 at age 90. B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August. Who can we claim as an Idaho writer? Must they be born here, as Ezra Pound was? He had not learned to write his name when he moved away from the state, never to return. How about Ernest Hemingway, who wasn’t born here but lived and wrote in the state?

Or, how about someone who never really took up residence here, but wrote two novels in Idaho? Discuss among yourselves, but that criteria allows me to write a little Idaho story about an author who was wildly popular at one time.

B.M. Bower wrote, by my count, 68 novels—many still in print—and over a dozen screenplays. She is often favorably compared with Zane Grey, one of her contemporaries.

She was born Bertha Muzzy in 1871. Her family moved from Minnesota to a dryland homestead near Great Falls, Montana in 1889. At age 19, she eloped with a homesteader cowboy named Clayton Bower, thus giving her the pen name she would use for the rest of her life. Rather than Bertha Muzzy Bower, she chose B.M. so that readers could assume she was a man.

She would marry three men, divorcing two of them, and teaching one, her second husband Bill Sinclair, how to write a Western novel. He wrote 15 of his own.

Bower wrote her novels from homes in Montana, Washington, and California. She wrote two of them in Idaho, on brief visits. The Good Indian was written while she visited the ranch home of David Bliss, for whom Bliss, Idaho is named.

Bower’s second Idaho book was called Ranch at the Wolverine . She pumped that one out during a stay of about two months in 1913 at the home of my Great Aunt Agnes Just Reid, best known for her book Letters of Long Ago . The Just/Reid family home is in the Blackfoot River Valley below Wolverine Canyon. Agnes and B.M. spent much of that summer riding horses, exploring the canyon, and often riding into Blackfoot, about 15 miles away.

B.M. Bower loved to write details into her books from personal experience. In September 1913 the War Bonnet Roundup would take place in Idaho Falls. There was to be a women’s saddle horse race, and Bower talked Agnes into riding the 18 miles to the Roundup and entering the race the next day.

Agnes Just Reid remembered it this way: “Bower wanted to ride in the race for the sensation of it. Dressed in our long, divided, skirts of corduroy, so the wind would not blow them and show our ankles, we raced our fat, old cattle horses around the track far behind the professionals. But we got our sensation and the dust.”

Ranch of the Wolverine and The Good Indian are still in print.

In our family archives we have a B.M. Bower manuscript with charred edges that survived a fire in the home of Agnes and Robert E. Reid. When I learned that, I thought we might have a rare, unpublished novel by Bower. Alas, the manuscript was not unique and the novel was among the dozens she published.

Bower passed away in 1940 at age 69. Her friend, Agnes Just Reid, passed away in 1976 at age 90.

B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

B.M. Bower, courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society's physical photo collection.

Published on August 24, 2021 04:00

August 23, 2021

Pioneer Home Catches Fire

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

(Editor’s note: The following is a manuscript written by Agnes Just Reid in 1968 for a writing contest, probably sponsored by the Idaho Writers League. Comments from a judge were clipped to the manuscript. Some of the suggested stylistic changes have been made. The judge didn’t think the black cat was a necessary element of the story, and I agree. Nevertheless, it has been left in to honor the original intention of the writer. To help modern readers better understand what family members were involved, we have made some comments in brackets. The incident took place in 1931.)

The Black Cat

By Agnes Just Reid

I can still hear myself screaming: “The house is on fire!” And, I see my husband, who had been sound asleep beside me, landing in the middle of the floor at four o’clock on a July morning, and following a peculiar light that filled our house. The light was reflected down from the second floor where the steep stairway led up to sleeping rooms, but there was no door either below or above the stairs.

It wasn’t a roaring inferno that greeted him, just a quiet fire that you could almost believe was in a fireplace, but it filled the entire space, a storage room, between the two sleeping rooms on the second floor.

After the first realization, I have very little recollection of what I did or thought, but it must have been almost as soon as I gave that wild alarm that one thought flitted through my mind: “That black cat crossed just ahead of the car as we came from the show last night.”

It was the only home I had ever known. It was the only home my husband had ever known for his mother had died when he was twelve and he had been a “pillar to post” person, living where he could find work.

We had prided ourselves on being the most unsuperstitious family in the world and on this particular night, we had reached the height of happiness. Our oldest son had been married one month, bringing us the daughter that we’d needed so long, the sister for our five sons. [Eldro and Gerry were married June 5, 1930] Our youngest [Wallace] was one year old and we had all had an evening out seeing Will Rogers in So this is London. Life was good.

This home was not just a house. It was an achievement of the pioneers of Snake River Valley and at the time it was built [1887] it was the most comfortable home for miles around. What might have been the basement was built at a lower level, two thick stone rooms that fitted into the hillside, with beams a foot in diameter, peeled and shining. In this room was kept the supplies, a thousand pounds of flour set up on an open foundation so that the cats could travel through the tunnels and overtake a stray mouse that might invade the sport. Beans and rice and dried fruits and canned goods were stored there in proportions to match the flour. By the time my people had graduated from the “dugout” epoch and the log cabin epoch, they had reached the time when many helpers had to be employed and helpers then were part of the family.

The second basement room was a milk cellar, with long shelves that would hold thirty-two big pans of milk while the cream raised. It was the cleanest, coolest place I the world with its dirt floor that was always a little damp so there was never a speck of dust and the ten-gallon barrel churn, the butter bowl that could handle twelve pounds of butter and the handmade cedar butter paddle were all the pride of my mother’s heart.

She loved the butter industry. I always wondered if it took away some of the back-break, because Thomas Moran the greatest Nature artist of his time had once visited her humble home and as he stood in the cellar drinking buttermilk, he looked at the long rows of butter she had just smoothed with her cedar paddle and asked, “Mrs. Just, what do you use to polish your rolls of butter?”

A short flight of stairs ran up from the storage room into the thirty-six-foot kitchen where that stack of flour soon became loaves of bread by the alchemy of my mother’s hands and a bottle of everlasting yeast.

Midway of the east wall of the kitchen a hall ran to the front porch. On one side of the hall, two small sleeping rooms, on the other side the living room, called at the time “the big room.”

It was a multipurpose room. Many times, it was a hospital. I could remember very well when my mother had been confined there for six long weeks. I was eleven and during that period I learned to make bread and order groceries. My first list had a request for six pounds of mustard. We did not run out of mustard for a great many years.

This room was also the Presto Post Office for fourteen years. It was there my husband first said “Hello” to me as he stopped to ask for mail when I was home on winter vacation [from attending Albion Normal School].

It was also in this roomy room that three of our five sons were born. The third one [Fred] saw fit to come even before the doctor did, but he did not seem embarrassed, and his father knew just what to do with any newborn thing. Ten years later the same son almost died of measles in that room. Twenty-three years later he was married under the Christmas tree in the same room. [Fred and Alma were married December 27, 1942] That house was our home.

Somehow we got organized [to fight the fire]. My husband stood on the stairs and threw buckets of water that the ground force delivered to him at the ever-spreading flames. The house was 40 years old [actually 43 years old]. Every board and rafter was as dry as tinder.

We are not a noisy family so it was all done quietly, so quietly that the youngest members of the family continued to sleep after their night out, babies both of them, one [Doug] was three.

The sixteen-year-old [Vin] had a friend visiting him about his own age. They ran the buckets and the younger boy [Fred] helped fill the buckets at the kitchen sink, then when the supply of water ran low, he “manned” what we called the black pump which was not connected with the windmill.

It was before the days of electricity so wind power was all we had and wind was the thing we prayed would not come on that particular night. In fact, there had been a few drops of rain during the time we were at the show, the grass was set when we got out of the car but the moon was bright.

That was the part that always made us wonder what wakened me. Never during the whole episode was there any smell of smoke on the first floor and there was no crackling or roar of fire. Was the light of the fire enough brighter than the moonlight to arouse me from a sound sleep? Who can say?

How long the battle raged I have no idea. I do know that never a soldier in the trenches fought harder for home and country than my husband did during those terrifying hours. He kept saying he could manage it when I would suggest calling the neighbors a mile away. We never even considered calling the fire truck twenty miles away for we knew the battle would be either won or lost before they could come over unimproved roads.

Once when the fire began to break through the shingles my husband called to me: “Better get the babies out, Mom.” I was prepared to put them in the car whenever there seemed to be no hope of saving anything but ourselves

After that the confusion increased. The water boys had to transfer their operations to the outside of the house and the shingles were just wet enough to be slippery. Just as I turned from closing the car door on two screaming boys, our oldest helper came skiing down the roof, long legs swaying and crashed at my feet from the edge of an eight-foot porch.

I could not imagine anything less than a broken leg from such an experience, but he only groaned a little and went back to fill his bucket.

“Water quenches fire.” The fire was quenched but the water was still to be reckoned with. There was no time to rest. The furniture had to be gotten out of the first-floor rooms to keep everything from being ruined by water instead of fire. No one could imagine the water that had been used until it came ripping back ruining every ceiling as it came.

When the weary workers and the babies went back to sleep, my husband and I drank a cup of coffee in the kitchen that was still intact and he said very quietly, “That damned black cat. Why didn’t I kill him?”

A little later the insurance adjusters came and listed the things they would pay for, among them the winter coat belonging to our bride that had cost her a whole month’s salary. We felt very lucky that July day. The date of this photo is uncertain, but the front of the home would have looked like this in 1931. The tiny dormer on the roof marks the site of the upstairs rooms where the fire took place.

The date of this photo is uncertain, but the front of the home would have looked like this in 1931. The tiny dormer on the roof marks the site of the upstairs rooms where the fire took place.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

(Editor’s note: The following is a manuscript written by Agnes Just Reid in 1968 for a writing contest, probably sponsored by the Idaho Writers League. Comments from a judge were clipped to the manuscript. Some of the suggested stylistic changes have been made. The judge didn’t think the black cat was a necessary element of the story, and I agree. Nevertheless, it has been left in to honor the original intention of the writer. To help modern readers better understand what family members were involved, we have made some comments in brackets. The incident took place in 1931.)

The Black Cat

By Agnes Just Reid

I can still hear myself screaming: “The house is on fire!” And, I see my husband, who had been sound asleep beside me, landing in the middle of the floor at four o’clock on a July morning, and following a peculiar light that filled our house. The light was reflected down from the second floor where the steep stairway led up to sleeping rooms, but there was no door either below or above the stairs.

It wasn’t a roaring inferno that greeted him, just a quiet fire that you could almost believe was in a fireplace, but it filled the entire space, a storage room, between the two sleeping rooms on the second floor.

After the first realization, I have very little recollection of what I did or thought, but it must have been almost as soon as I gave that wild alarm that one thought flitted through my mind: “That black cat crossed just ahead of the car as we came from the show last night.”

It was the only home I had ever known. It was the only home my husband had ever known for his mother had died when he was twelve and he had been a “pillar to post” person, living where he could find work.

We had prided ourselves on being the most unsuperstitious family in the world and on this particular night, we had reached the height of happiness. Our oldest son had been married one month, bringing us the daughter that we’d needed so long, the sister for our five sons. [Eldro and Gerry were married June 5, 1930] Our youngest [Wallace] was one year old and we had all had an evening out seeing Will Rogers in So this is London. Life was good.

This home was not just a house. It was an achievement of the pioneers of Snake River Valley and at the time it was built [1887] it was the most comfortable home for miles around. What might have been the basement was built at a lower level, two thick stone rooms that fitted into the hillside, with beams a foot in diameter, peeled and shining. In this room was kept the supplies, a thousand pounds of flour set up on an open foundation so that the cats could travel through the tunnels and overtake a stray mouse that might invade the sport. Beans and rice and dried fruits and canned goods were stored there in proportions to match the flour. By the time my people had graduated from the “dugout” epoch and the log cabin epoch, they had reached the time when many helpers had to be employed and helpers then were part of the family.

The second basement room was a milk cellar, with long shelves that would hold thirty-two big pans of milk while the cream raised. It was the cleanest, coolest place I the world with its dirt floor that was always a little damp so there was never a speck of dust and the ten-gallon barrel churn, the butter bowl that could handle twelve pounds of butter and the handmade cedar butter paddle were all the pride of my mother’s heart.

She loved the butter industry. I always wondered if it took away some of the back-break, because Thomas Moran the greatest Nature artist of his time had once visited her humble home and as he stood in the cellar drinking buttermilk, he looked at the long rows of butter she had just smoothed with her cedar paddle and asked, “Mrs. Just, what do you use to polish your rolls of butter?”

A short flight of stairs ran up from the storage room into the thirty-six-foot kitchen where that stack of flour soon became loaves of bread by the alchemy of my mother’s hands and a bottle of everlasting yeast.

Midway of the east wall of the kitchen a hall ran to the front porch. On one side of the hall, two small sleeping rooms, on the other side the living room, called at the time “the big room.”

It was a multipurpose room. Many times, it was a hospital. I could remember very well when my mother had been confined there for six long weeks. I was eleven and during that period I learned to make bread and order groceries. My first list had a request for six pounds of mustard. We did not run out of mustard for a great many years.

This room was also the Presto Post Office for fourteen years. It was there my husband first said “Hello” to me as he stopped to ask for mail when I was home on winter vacation [from attending Albion Normal School].

It was also in this roomy room that three of our five sons were born. The third one [Fred] saw fit to come even before the doctor did, but he did not seem embarrassed, and his father knew just what to do with any newborn thing. Ten years later the same son almost died of measles in that room. Twenty-three years later he was married under the Christmas tree in the same room. [Fred and Alma were married December 27, 1942] That house was our home.

Somehow we got organized [to fight the fire]. My husband stood on the stairs and threw buckets of water that the ground force delivered to him at the ever-spreading flames. The house was 40 years old [actually 43 years old]. Every board and rafter was as dry as tinder.

We are not a noisy family so it was all done quietly, so quietly that the youngest members of the family continued to sleep after their night out, babies both of them, one [Doug] was three.

The sixteen-year-old [Vin] had a friend visiting him about his own age. They ran the buckets and the younger boy [Fred] helped fill the buckets at the kitchen sink, then when the supply of water ran low, he “manned” what we called the black pump which was not connected with the windmill.

It was before the days of electricity so wind power was all we had and wind was the thing we prayed would not come on that particular night. In fact, there had been a few drops of rain during the time we were at the show, the grass was set when we got out of the car but the moon was bright.

That was the part that always made us wonder what wakened me. Never during the whole episode was there any smell of smoke on the first floor and there was no crackling or roar of fire. Was the light of the fire enough brighter than the moonlight to arouse me from a sound sleep? Who can say?

How long the battle raged I have no idea. I do know that never a soldier in the trenches fought harder for home and country than my husband did during those terrifying hours. He kept saying he could manage it when I would suggest calling the neighbors a mile away. We never even considered calling the fire truck twenty miles away for we knew the battle would be either won or lost before they could come over unimproved roads.

Once when the fire began to break through the shingles my husband called to me: “Better get the babies out, Mom.” I was prepared to put them in the car whenever there seemed to be no hope of saving anything but ourselves

After that the confusion increased. The water boys had to transfer their operations to the outside of the house and the shingles were just wet enough to be slippery. Just as I turned from closing the car door on two screaming boys, our oldest helper came skiing down the roof, long legs swaying and crashed at my feet from the edge of an eight-foot porch.

I could not imagine anything less than a broken leg from such an experience, but he only groaned a little and went back to fill his bucket.

“Water quenches fire.” The fire was quenched but the water was still to be reckoned with. There was no time to rest. The furniture had to be gotten out of the first-floor rooms to keep everything from being ruined by water instead of fire. No one could imagine the water that had been used until it came ripping back ruining every ceiling as it came.

When the weary workers and the babies went back to sleep, my husband and I drank a cup of coffee in the kitchen that was still intact and he said very quietly, “That damned black cat. Why didn’t I kill him?”

A little later the insurance adjusters came and listed the things they would pay for, among them the winter coat belonging to our bride that had cost her a whole month’s salary. We felt very lucky that July day.

The date of this photo is uncertain, but the front of the home would have looked like this in 1931. The tiny dormer on the roof marks the site of the upstairs rooms where the fire took place.

The date of this photo is uncertain, but the front of the home would have looked like this in 1931. The tiny dormer on the roof marks the site of the upstairs rooms where the fire took place.

Published on August 23, 2021 04:00

August 22, 2021

A Brand that Fit to a T

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The Just and Reid families have had several cattle brands over the years, acquiring a new one when some family member began to ranch on their own.

The first Just brand, the one used by Nels and Emma Just, was a mystery to many in the family. It was a simple capital T, which stood for…? T is so close to a J, that one might be tempted to ask why Nels didn’t just bend that iron a bit.

The answer came to light when we uncovered a carbon of a letter from James Just, eldest son of Nels and Emma, written to Mary Louise Johnesse, state brand recorder. The letter was dated January 1, 1936 and was in answer to a request for the history of the T brand. James Just replied:

“First, the brand was given to him [Nels Just] by a blacksmith at the soldiers’ post in Lincoln Valley [the military Fort Hall] in Oneida county Idaho in 1871. The same branding iron, almost destroyed by fire and rust, is still on the premises here although we have used many irons since. Mr. Reid, who is the husband of Agnes Just Reid, the only daughter of N.A. Just, still uses the brand. As to how many cattle there were in the herd, possibly ten or twelve thousand head carried the T brand and about two hundred and fifty head of horses during that period of time. Mrs. Reid still lives on the original homestead of our father, N. A. Just, where a family of five boys and five girls were born [only one girl, Agnes, lived longer that a few weeks]. The cattle with the T brand still run on the same range and are being wintered on the same ranch that they have been for the passed (sic) 64 years. Our Post Office has been changed eight different times without changing our residence. We have lived through the period where we got out mail by chance once in thirty days up until now when we have a daily rural delivery.”

So, the brand was a T because that’s the shape of brand that someone gave to Nels. It’s about the simplest configuration possible.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The Just and Reid families have had several cattle brands over the years, acquiring a new one when some family member began to ranch on their own.

The first Just brand, the one used by Nels and Emma Just, was a mystery to many in the family. It was a simple capital T, which stood for…? T is so close to a J, that one might be tempted to ask why Nels didn’t just bend that iron a bit.

The answer came to light when we uncovered a carbon of a letter from James Just, eldest son of Nels and Emma, written to Mary Louise Johnesse, state brand recorder. The letter was dated January 1, 1936 and was in answer to a request for the history of the T brand. James Just replied:

“First, the brand was given to him [Nels Just] by a blacksmith at the soldiers’ post in Lincoln Valley [the military Fort Hall] in Oneida county Idaho in 1871. The same branding iron, almost destroyed by fire and rust, is still on the premises here although we have used many irons since. Mr. Reid, who is the husband of Agnes Just Reid, the only daughter of N.A. Just, still uses the brand. As to how many cattle there were in the herd, possibly ten or twelve thousand head carried the T brand and about two hundred and fifty head of horses during that period of time. Mrs. Reid still lives on the original homestead of our father, N. A. Just, where a family of five boys and five girls were born [only one girl, Agnes, lived longer that a few weeks]. The cattle with the T brand still run on the same range and are being wintered on the same ranch that they have been for the passed (sic) 64 years. Our Post Office has been changed eight different times without changing our residence. We have lived through the period where we got out mail by chance once in thirty days up until now when we have a daily rural delivery.”

So, the brand was a T because that’s the shape of brand that someone gave to Nels. It’s about the simplest configuration possible.

Published on August 22, 2021 04:00

August 21, 2021

Moving the Nels Just Shop

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

How could something as useful as a ranch shop be so in the way?

We don’t know exactly when Nels Just built his shop, but it was likely in the 1870s. He used it as a blacksmith shop and a place to work on projects out of the weather. His father, Peder Anderson Just, lived in the shop for a little while near the end of his life.

Nels cut the logs using his own sawmill that moved from place to place on a timber allotment in the Blackfoot Mountains a few miles from his homestead. He erected the shop in a low-lying flat spot below his residence, which stood on a low hill. That residence was a cabin, at first, then Nels replaced with a frame house, and finally with a brick home in 1887.

The “low-lying” part about the location was often a headache. Water pooled up around both sides of the shop after rainstorms and the road running on either side of it was often a muddy mess.

Nels’ shop fell out of use over the years as his descendants built more modern structures that better met the needs of ranching and farming operations as tractors and trucks replaced horses and wagons.

In 2003 family members who were operating the ranches in the valley at the time decided to move the shop out of the way of their operations. Using a hydraulic lift on a tractor and plenty of hands to help, they moved the old shop log by log and reassembled it about 75 yards away where it could serve as a shelter for small machines such as ATVs.

The second life of the Nels Just shop lasted 18 years. In 2021, a new generation of farmers and ranchers decided the shop was in the way, again. After considerable debate the board members of the Presto Preservation Association, our family nonprofit, decided to move the shop a hundred yards up the hill and onto a concrete foundation.

On August 14, about a dozen descendants of Nels and Emma Just hand-carried the logs to the new foundation and reassembled the shop there, where it will remain for the foreseeable future. It is now located on PPA property, dedicated to the preservation of family history, where it will be used as a storage site for tents, table, chairs, and other necessities for Just-Reid family reunions.

This 1969 photo shows the Nels Just shop, lower right, in its original location.

This 1969 photo shows the Nels Just shop, lower right, in its original location.  The south end of the shop before it was moved in 2003.

The south end of the shop before it was moved in 2003.  That's Justin Oleson guiding a log during the reassembly of the shop in 2003.

That's Justin Oleson guiding a log during the reassembly of the shop in 2003.  Justin Oleson 18 years later, in 2021, making some minor adjustments at the new permanent home of the Nels Just Shop.

Justin Oleson 18 years later, in 2021, making some minor adjustments at the new permanent home of the Nels Just Shop.  Rich Reid guides one in.

Rich Reid guides one in.  The bulk of the work is done!

The bulk of the work is done!

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

How could something as useful as a ranch shop be so in the way?

We don’t know exactly when Nels Just built his shop, but it was likely in the 1870s. He used it as a blacksmith shop and a place to work on projects out of the weather. His father, Peder Anderson Just, lived in the shop for a little while near the end of his life.

Nels cut the logs using his own sawmill that moved from place to place on a timber allotment in the Blackfoot Mountains a few miles from his homestead. He erected the shop in a low-lying flat spot below his residence, which stood on a low hill. That residence was a cabin, at first, then Nels replaced with a frame house, and finally with a brick home in 1887.

The “low-lying” part about the location was often a headache. Water pooled up around both sides of the shop after rainstorms and the road running on either side of it was often a muddy mess.

Nels’ shop fell out of use over the years as his descendants built more modern structures that better met the needs of ranching and farming operations as tractors and trucks replaced horses and wagons.

In 2003 family members who were operating the ranches in the valley at the time decided to move the shop out of the way of their operations. Using a hydraulic lift on a tractor and plenty of hands to help, they moved the old shop log by log and reassembled it about 75 yards away where it could serve as a shelter for small machines such as ATVs.

The second life of the Nels Just shop lasted 18 years. In 2021, a new generation of farmers and ranchers decided the shop was in the way, again. After considerable debate the board members of the Presto Preservation Association, our family nonprofit, decided to move the shop a hundred yards up the hill and onto a concrete foundation.

On August 14, about a dozen descendants of Nels and Emma Just hand-carried the logs to the new foundation and reassembled the shop there, where it will remain for the foreseeable future. It is now located on PPA property, dedicated to the preservation of family history, where it will be used as a storage site for tents, table, chairs, and other necessities for Just-Reid family reunions.

This 1969 photo shows the Nels Just shop, lower right, in its original location.

This 1969 photo shows the Nels Just shop, lower right, in its original location.  The south end of the shop before it was moved in 2003.

The south end of the shop before it was moved in 2003.  That's Justin Oleson guiding a log during the reassembly of the shop in 2003.

That's Justin Oleson guiding a log during the reassembly of the shop in 2003.  Justin Oleson 18 years later, in 2021, making some minor adjustments at the new permanent home of the Nels Just Shop.

Justin Oleson 18 years later, in 2021, making some minor adjustments at the new permanent home of the Nels Just Shop.  Rich Reid guides one in.

Rich Reid guides one in.  The bulk of the work is done!

The bulk of the work is done!

Published on August 21, 2021 04:00

August 20, 2021

A Tradition of Family Reunions

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The Just family has held family reunions each August since 1904. We might have taken a year or two off during the wars, but no one is around to confirm that. Last year, COVID 19 kept us from getting together. This year we held our reunion in conjunction with the Sesquicentennial Plus One celebration at the homestead.

Here are some memories and news reports from the earliest reunions.

by Emma Just

The Just annual gathering began in 1904 the second Sunday of August being the 14th. All were present and enjoyed it very much. Ten Grandchildren there. The next was August 13th '05 also another very happy event, all present, two more added to our number making twelve grandchildren.

The next was August 12 '06 one more added to our number making 13 in the grand count, and such a terrific storm we had. I shall always be glad I am not in the Grove when a thunder storm rages.

Our next was held August 11 '07. Still the odd number of 13 Grandchildren, all such healthy robust kids four boys and nine girls. Bless each one, may they all be good. It was such a beautiful day and we were so happy. Daddy Just was not with us. He don't want to join our picnics. Well he must have his way and we must be satisfied. Had a dear girlfriend tho (our Beck).*

* "our Beck" refers to Rebeccah Wright Hayes, Blackfoot, and later of Idaho Falls, long time Just family friend.

Annual Picnic at the Just Ranch

(Editor's note: The following are two clippings from the Blackfoot newspaper in the early years of this century)

Sunday, August 9th, was the fifth annual picnic of the Justs in the grove on their timber culture, which is Patent No. 1 in the state and located near Presto.

At about 10:30 the picnicers (sic) began to arrive from all sides and at one o' clock the luncheon was served all helping themselves at a long table and then hunting a good shady place to eat and have a good social time.

Everyone is welcome to these picnics. There are no invitations, but the glad hand is extended to all who come to participate in the pleasures of the day. The event always occurs on the second Sunday in August as at that time the first haying is over and before the second cutting.

The first picnic was held on the 14th, '04 the next on the 13th in ‘05, the third on the 15th in '06, the fourth on the 11th in '07 and this one in '08 on the 9th. All dates are cut in the trees. Swings were put up on this occasion and young and old enjoyed the fun. Games were played, all joining in and songs were sung with a little organ to help, and a good graphophone added to the pleasure.

One little ceremony which is a feature of these affairs to get all the grandchildren with their grandmother Just to stand on a historic quilt made by their great grandmother in Idaho at Soda Springs in '64. It has crossed the sea twice. More foot room is needed now than the first time this took place, as four new grandchildren have been added, making fourteen in all, the youngest being held by the grandmother. This pretty custom will be kept up during her life and still be remembered by many afterwards.

Seventh Annual Reunion Held

One of the enjoyable events of the season to which we have been invited this year, was the annual reunion of the Just family held in their big grove below the Just ranch house on the Blackfoot river last Sunday. Big Justs and little Justs and their innumerable friends for miles around were there. Baskets, pans and boxes of yellow legged chicken appeared on the festal board and disappeared as rapidly. There were cakes with chocolate, cakes with coconut and cakes with every manner of good stuff on them, but in an hour after the feast was spread, the big table under the swaying trees looked as if it had been hit by about one hundred hungry people, and it had. The day was ideal and everyone had a delightful time. It was the seventh annual reunion of the family.

In the Presto News section columns:

1908, On Sunday last occurred the annual picnic in the Just grove, the was ideal and about seventy persons availed themselves of the opportunity to rest and enjoy nature.

1909 The annual picnic in the grove was held last Sunday and largely attended by both the Just and the un-Just.

At the early family reunions Emma would gather her grandchildren around her for a photo on a quilt made by her mother. This one is from about 1910.

At the early family reunions Emma would gather her grandchildren around her for a photo on a quilt made by her mother. This one is from about 1910.  During Idaho's Centennial in 1990 the family gathered for a group photo at the reunion. The 1887 Nels and Emma Just house is to the left in the picture.

During Idaho's Centennial in 1990 the family gathered for a group photo at the reunion. The 1887 Nels and Emma Just house is to the left in the picture.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

The Just family has held family reunions each August since 1904. We might have taken a year or two off during the wars, but no one is around to confirm that. Last year, COVID 19 kept us from getting together. This year we held our reunion in conjunction with the Sesquicentennial Plus One celebration at the homestead.

Here are some memories and news reports from the earliest reunions.

by Emma Just

The Just annual gathering began in 1904 the second Sunday of August being the 14th. All were present and enjoyed it very much. Ten Grandchildren there. The next was August 13th '05 also another very happy event, all present, two more added to our number making twelve grandchildren.

The next was August 12 '06 one more added to our number making 13 in the grand count, and such a terrific storm we had. I shall always be glad I am not in the Grove when a thunder storm rages.

Our next was held August 11 '07. Still the odd number of 13 Grandchildren, all such healthy robust kids four boys and nine girls. Bless each one, may they all be good. It was such a beautiful day and we were so happy. Daddy Just was not with us. He don't want to join our picnics. Well he must have his way and we must be satisfied. Had a dear girlfriend tho (our Beck).*

* "our Beck" refers to Rebeccah Wright Hayes, Blackfoot, and later of Idaho Falls, long time Just family friend.

Annual Picnic at the Just Ranch

(Editor's note: The following are two clippings from the Blackfoot newspaper in the early years of this century)

Sunday, August 9th, was the fifth annual picnic of the Justs in the grove on their timber culture, which is Patent No. 1 in the state and located near Presto.

At about 10:30 the picnicers (sic) began to arrive from all sides and at one o' clock the luncheon was served all helping themselves at a long table and then hunting a good shady place to eat and have a good social time.

Everyone is welcome to these picnics. There are no invitations, but the glad hand is extended to all who come to participate in the pleasures of the day. The event always occurs on the second Sunday in August as at that time the first haying is over and before the second cutting.

The first picnic was held on the 14th, '04 the next on the 13th in ‘05, the third on the 15th in '06, the fourth on the 11th in '07 and this one in '08 on the 9th. All dates are cut in the trees. Swings were put up on this occasion and young and old enjoyed the fun. Games were played, all joining in and songs were sung with a little organ to help, and a good graphophone added to the pleasure.

One little ceremony which is a feature of these affairs to get all the grandchildren with their grandmother Just to stand on a historic quilt made by their great grandmother in Idaho at Soda Springs in '64. It has crossed the sea twice. More foot room is needed now than the first time this took place, as four new grandchildren have been added, making fourteen in all, the youngest being held by the grandmother. This pretty custom will be kept up during her life and still be remembered by many afterwards.

Seventh Annual Reunion Held

One of the enjoyable events of the season to which we have been invited this year, was the annual reunion of the Just family held in their big grove below the Just ranch house on the Blackfoot river last Sunday. Big Justs and little Justs and their innumerable friends for miles around were there. Baskets, pans and boxes of yellow legged chicken appeared on the festal board and disappeared as rapidly. There were cakes with chocolate, cakes with coconut and cakes with every manner of good stuff on them, but in an hour after the feast was spread, the big table under the swaying trees looked as if it had been hit by about one hundred hungry people, and it had. The day was ideal and everyone had a delightful time. It was the seventh annual reunion of the family.

In the Presto News section columns:

1908, On Sunday last occurred the annual picnic in the Just grove, the was ideal and about seventy persons availed themselves of the opportunity to rest and enjoy nature.

1909 The annual picnic in the grove was held last Sunday and largely attended by both the Just and the un-Just.

At the early family reunions Emma would gather her grandchildren around her for a photo on a quilt made by her mother. This one is from about 1910.

At the early family reunions Emma would gather her grandchildren around her for a photo on a quilt made by her mother. This one is from about 1910.  During Idaho's Centennial in 1990 the family gathered for a group photo at the reunion. The 1887 Nels and Emma Just house is to the left in the picture.

During Idaho's Centennial in 1990 the family gathered for a group photo at the reunion. The 1887 Nels and Emma Just house is to the left in the picture.

Published on August 20, 2021 04:00

August 19, 2021

When Nels Just was Laid to Rest

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Editor’s Note: The following account was taken from an article written for Presto Press in 1989. The author was the only one living at the time who could remember the event.

By Mabel Bennett Hutchinson

Grandfather Just died on March 28, 1912. I have some vivid memories of that funeral. You know, of course, about the cemetery that is near the Just house. During the years that Emma and Nels had lived there, several deaths had occurred shortly after birth, and this started the little graveyard on the hill, just north of the brick house. When we were young, we used to go up on the hill and look at the graves. Most of them were caved in and sagebrush grew over them.

The Justs made no effort to fence or protect those graves, as it was their philosophy that “dust thou art, to dust returneth,” and they let nature take care of the graves.

Uncle Charlie Just was also buried in this family graveyard. He had died in 1907 when I was too young to remember anything about his death or funeral. He was only 29 when he died. I remember how his daughters Virginia, Katie and Treo used to carry flowers to his grave and I would go along with them. I thought it was a beautiful thing to do, but it angered Grandma to have flowers left there, as she preferred that the graves remain part of the hillside in a natural state. She had always been opposed to giving flowers to the dead.

When Grandfather Just died, he was buried there and, as a child of nine, I have a vivid recollection of that burial. I would like to present this experience with my imagination thrown in, so that some of the reality comes through to you. Of course, I do not remember (everything) that took place, but the setting there on that hill is fresh in my memory, for this was the time that I first saw a dead body.

It was a queer procession that left the Just house. Brother and I rode with Papa in our wagon, as we were carrying the casket. Just behind us, Uncle Jim’s family came in their wagon. Walking behind them was Mama, Aunt Agnes, and Uncle Rufus. We crossed the little canal bridge and the horses’ heavy feet beat against the hollow sounding boards, then we left the road to climb the steep hill to the graves. No wagon ever climbed the hill except to get to the graves, and from year to year the sagebrush grew over the tracks so there was no road. The wheels of the wagon would climb up over the large sagebrush, crushing it to the ground. It made the horses strain in the big leather tugs to pull the heavy wagon and the load. The sun was getting low and a few scattered clouds were tinted pink and gold. The cold wind sighed through the sagebrush and from down in the valley came the lowing of the cattle and the faint sound of the flowing river.

As we drew near the graves, we could see the high mound of brown clay where the men had dug the grave. Papa reined the horses over by it and then pulled the big wagon as near to the grave as possible. Uncle Jim and his family stopped their wagon a little way off from the grave. Papa got down from the wagon and we all got out. Papa took his lasso and stretched it across the ground where they were going to set the casket. Uncle Rufus had his lasso, too, and he laid it down, not far from Papa’s. When they set the casket down on the ropes, they would be able to lower it into the grave.

Everyone wanted to see Gramp before they laid him away forever, so Papa lifted the lid and we all walked over near the casket. I could not believe this still, white face could be Gramp, but that was his nose, and his mustache and, as I looked closely, it seemed as if I could see the very roots of the hairs in his mustache. There was Gramp’s finger that was cut off at the end, too. Aunt Crillia was crying, and the children were all leaning over the wagon box staring at Gramp. Then they closed the casket.

Papa, Uncle Rufus, Uncle Jim and his eldest son, Leslie, took the ends of the lassos and lowered the big box into the grave.

After this, everyone left but Papa and Uncle Rufus, who would fill the grave with the fresh brown clay. Nels Just in his later years. He passed away March 18, 1912, having contracted pneumonia

Nels Just in his later years. He passed away March 18, 1912, having contracted pneumonia

following an operation in Salt Lake City.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Editor’s Note: The following account was taken from an article written for Presto Press in 1989. The author was the only one living at the time who could remember the event.

By Mabel Bennett Hutchinson

Grandfather Just died on March 28, 1912. I have some vivid memories of that funeral. You know, of course, about the cemetery that is near the Just house. During the years that Emma and Nels had lived there, several deaths had occurred shortly after birth, and this started the little graveyard on the hill, just north of the brick house. When we were young, we used to go up on the hill and look at the graves. Most of them were caved in and sagebrush grew over them.

The Justs made no effort to fence or protect those graves, as it was their philosophy that “dust thou art, to dust returneth,” and they let nature take care of the graves.

Uncle Charlie Just was also buried in this family graveyard. He had died in 1907 when I was too young to remember anything about his death or funeral. He was only 29 when he died. I remember how his daughters Virginia, Katie and Treo used to carry flowers to his grave and I would go along with them. I thought it was a beautiful thing to do, but it angered Grandma to have flowers left there, as she preferred that the graves remain part of the hillside in a natural state. She had always been opposed to giving flowers to the dead.

When Grandfather Just died, he was buried there and, as a child of nine, I have a vivid recollection of that burial. I would like to present this experience with my imagination thrown in, so that some of the reality comes through to you. Of course, I do not remember (everything) that took place, but the setting there on that hill is fresh in my memory, for this was the time that I first saw a dead body.

It was a queer procession that left the Just house. Brother and I rode with Papa in our wagon, as we were carrying the casket. Just behind us, Uncle Jim’s family came in their wagon. Walking behind them was Mama, Aunt Agnes, and Uncle Rufus. We crossed the little canal bridge and the horses’ heavy feet beat against the hollow sounding boards, then we left the road to climb the steep hill to the graves. No wagon ever climbed the hill except to get to the graves, and from year to year the sagebrush grew over the tracks so there was no road. The wheels of the wagon would climb up over the large sagebrush, crushing it to the ground. It made the horses strain in the big leather tugs to pull the heavy wagon and the load. The sun was getting low and a few scattered clouds were tinted pink and gold. The cold wind sighed through the sagebrush and from down in the valley came the lowing of the cattle and the faint sound of the flowing river.

As we drew near the graves, we could see the high mound of brown clay where the men had dug the grave. Papa reined the horses over by it and then pulled the big wagon as near to the grave as possible. Uncle Jim and his family stopped their wagon a little way off from the grave. Papa got down from the wagon and we all got out. Papa took his lasso and stretched it across the ground where they were going to set the casket. Uncle Rufus had his lasso, too, and he laid it down, not far from Papa’s. When they set the casket down on the ropes, they would be able to lower it into the grave.

Everyone wanted to see Gramp before they laid him away forever, so Papa lifted the lid and we all walked over near the casket. I could not believe this still, white face could be Gramp, but that was his nose, and his mustache and, as I looked closely, it seemed as if I could see the very roots of the hairs in his mustache. There was Gramp’s finger that was cut off at the end, too. Aunt Crillia was crying, and the children were all leaning over the wagon box staring at Gramp. Then they closed the casket.

Papa, Uncle Rufus, Uncle Jim and his eldest son, Leslie, took the ends of the lassos and lowered the big box into the grave.

After this, everyone left but Papa and Uncle Rufus, who would fill the grave with the fresh brown clay.

Nels Just in his later years. He passed away March 18, 1912, having contracted pneumonia

Nels Just in his later years. He passed away March 18, 1912, having contracted pneumoniafollowing an operation in Salt Lake City.

Published on August 19, 2021 04:00

August 18, 2021

Water on the Land

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Nels Just was not an engineer by trade, just by practice. His first effort to bring water to the land was a ditch from Willow Creek to the heart of where Idaho Falls is today. He dug the ditch by hand in 1871, completing the project. That same year he started a ditch on his property along the Blackfoot River. It would take him 17 years to finish that one. In the meantime, he and Emma carried water by the bucket from the river to their garden.

The irrigation project Nels is most remembered for was the construction of the Idaho Canal. It was the first big canal project in that part of the state. The Idaho Canal runs from about ten miles above Idaho Falls to the Blackfoot River, draining across the lower end of the valley where Nels and Emma lived, watering only a few acres of their son, James Just's property. But it irrigated 35,000 acres for other farmers.