Rick Just's Blog, page 115

September 6, 2021

An Idaho Balloonist

I find this one surprisingly hard to write. More about that in a moment.

Hawthorne C. Gray was a driven man. The Coeur d’Alene High School and University of Idaho graduate was the son of Captain W.P. Gray who piloted the steamer Georgie Oaks on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Hawthorne Gray joined the Idaho National Guard after graduating from U of I, and later the U.S. Army. Early on in his army career, in 1916, he fought in the Pancho Villa Expedition, serving as an infantry private. In 1917 he was commissioned a second lieutenant and in 1920 transferred to the U.S. Army Air Service as a captain. Shortly after that Gray caught the balloon bug.

He participated in some major balloon races, finishing second in the 1926 Gordon Bennett, the premiere race for gas balloonists. Then he set his sights on the altitude record for gas balloons. In 1927 he set an unofficial altitude record at 28,510 feet. He passed out during the attempt and awoke as the balloon was descending on its own just in time to throw off ballast and land safely.

In May that same year he went up again, smashing the altitude record for a human being by taking his balloon to 42,470 feet. But that record would remain unofficial. The balloon was dropping like a rock and he bailed out at 8,000 feet, parachuting to safety. Since he did not ride the bag down the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the organization that sanctioned such records, refused to recognize it.

So, back into the air. He made his third attempt in November 1927, rising ultimately to somewhere between 43,000 and 44,000 feet. Alas, once again he passed out. This time that proved fatal. Hawthorne Gray died in his final record attempt. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously.

That’s a sad story, but why would it be difficult for me to write? Because I had a friend and kayak partner who spent some years in the army, as did Gray. Carol was a flight surgeon. She was passionate about balloons, too, and once broke the altitude record for a woman in a gas balloon. She also won, along with ballooning partner Richard Abruzzo, the 2004 Gordon Bennett balloon race. They competed in that race twice more. In 2010 Carol Rymer Davis, driven in much the same way Hawthorne Gray was, went down with Richard Abruzzo over the Adriatic in a thunderstorm during the Gordon Bennett. They both died.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Hawthorne C. Gray was a driven man. The Coeur d’Alene High School and University of Idaho graduate was the son of Captain W.P. Gray who piloted the steamer Georgie Oaks on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

Hawthorne Gray joined the Idaho National Guard after graduating from U of I, and later the U.S. Army. Early on in his army career, in 1916, he fought in the Pancho Villa Expedition, serving as an infantry private. In 1917 he was commissioned a second lieutenant and in 1920 transferred to the U.S. Army Air Service as a captain. Shortly after that Gray caught the balloon bug.

He participated in some major balloon races, finishing second in the 1926 Gordon Bennett, the premiere race for gas balloonists. Then he set his sights on the altitude record for gas balloons. In 1927 he set an unofficial altitude record at 28,510 feet. He passed out during the attempt and awoke as the balloon was descending on its own just in time to throw off ballast and land safely.

In May that same year he went up again, smashing the altitude record for a human being by taking his balloon to 42,470 feet. But that record would remain unofficial. The balloon was dropping like a rock and he bailed out at 8,000 feet, parachuting to safety. Since he did not ride the bag down the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the organization that sanctioned such records, refused to recognize it.

So, back into the air. He made his third attempt in November 1927, rising ultimately to somewhere between 43,000 and 44,000 feet. Alas, once again he passed out. This time that proved fatal. Hawthorne Gray died in his final record attempt. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, posthumously.

That’s a sad story, but why would it be difficult for me to write? Because I had a friend and kayak partner who spent some years in the army, as did Gray. Carol was a flight surgeon. She was passionate about balloons, too, and once broke the altitude record for a woman in a gas balloon. She also won, along with ballooning partner Richard Abruzzo, the 2004 Gordon Bennett balloon race. They competed in that race twice more. In 2010 Carol Rymer Davis, driven in much the same way Hawthorne Gray was, went down with Richard Abruzzo over the Adriatic in a thunderstorm during the Gordon Bennett. They both died.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Hawthorne Gray getting ready for his final flight in 1927. Library of Congress photo.

Published on September 06, 2021 04:00

September 5, 2021

What was in that Safe?

George H. Pease seemed like a solid guy. He was the six-foot-six sheriff of Kootenai County in 1898 and he had put together a group of 112 men who were ready to volunteer to fight in the Spanish-American War. Governor Steunenberg took Captain Pease up on his offer, but needed just 50 men, and no officers. So, the Sheriff stayed home. He wouldn’t stay for long.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

On December 30, 1898, the sheriff lit out for Montana to bring a man who had broken out of the Kootenai County jail the previous summer back to face justice. Then, crickets. By January 7, 1899 county commissioners were beginning to get suspicious. Particularly since a new sheriff had been elected.

It was part of the duty of the sheriff to collect the money for saloon licenses in the county. Pease had done so in 1897, turning over $10,275 to the county treasurer. In 1898 he’d turned in just $7,300. That seemed a little short, since about ten new saloons had popped up.

Pease lived at the jail, so the commissioners had someone examine his quarters. All of the sheriff’s personal effects were gone. Mail for the sheriff was also piling up at the post office. The new sheriff was set to take office the following Monday. That’s when officials would open the office safe. Perhaps all would be right when they found a small pile of money inside along with receipt books.

Cynics (you know who you are) would expect the officials found the safe empty when Monday came around. Not so. The office keys were inside, along with a two-cent stamp. The departing sheriff had made off with somewhere between $4,000 and $5,000. To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would be the equivalent of about $150,000. The stamp would probably cost 55 cents, so, a bargain.

Published on September 05, 2021 04:00

September 4, 2021

Idaho's Freedom Riders

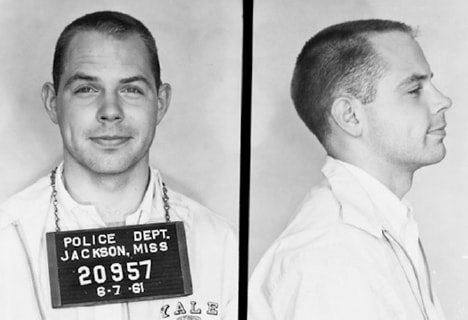

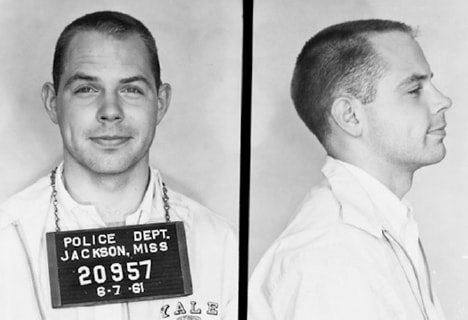

Some mugshots mean more than they would seem. Today we’re going to feature two men with strong Idaho ties who should be proud of their mugshots.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

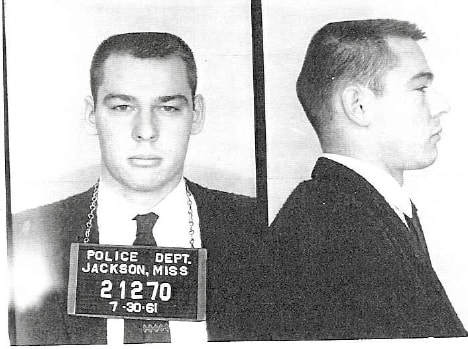

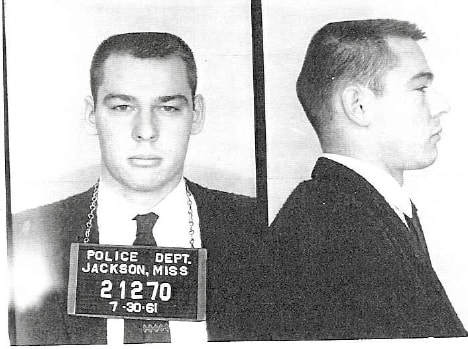

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement. Edward Kale's mugshot.

Edward Kale's mugshot.  Max Pavesic's mugshot.

Max Pavesic's mugshot.

Edward W. Kale grew up mostly in Grangeville. Some sources say he was born in Idaho and some say it was Iowa. That Idaho/Iowa thing, again, perhaps. Kale attended the University of Idaho but graduated from the University of Denver. He taught at the American colleges in Athens, Greece and Istanbul, Turkey, for three years before coming back stateside to get a degree at Yale Divinity in 1965. He is an ordained Methodist minister who taught and served as a college chaplain for years in England and Germany before coming back to Idaho to teach at the University of Idaho in 1978. He taught and served as a college chaplain at the University of Texas, and the University of Minnesota. Retired from that calling he now runs a kayaking service in Minnesota. He was active in the anti-war and anti-apartheid movements, and in supporting human rights in Central America.

The second mugshot belongs to Max Pavesic. He grew up in California getting degrees from Los Angeles City College and UCLA before getting an MA and PhD from the University of Colorado. Pavesic taught anthropology at Idaho State University for 1967-1971 and Boise State University until his retirement in 2001. He had chaired the department of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at BSU and was the recipient of many awards. Pavesic was an advisor to the Idaho Archeology Society and served as chair of the Idaho State Historical Society board of trustees. He lives today in Portland.

So, two academics with strong Idaho connections and mugshots in common. Why?

Both Edward W. Kale and Max Pavesic were arrested and jailed as Freedom Riders in 1961. The Freedom Riders risked their lives by taking public transportation as mixed-race riders that summer to spotlight local laws against it in the South. Discriminating against people based on the color of their skin was already against federal law, but many Southern jurisdiction flouted that and the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had yet to publish rules against it.

Edward Kale’s bus ride through several Southern states was largely uneventful until June 7, 1961. When they rolled into Jackson, Mississippi, he and other Freedom Riders boldly ignored the bus terminal signs, whites going to the waiting room marked “colored waiting room” and blacks going through the doors to the “white waiting room.” He spent several weeks in the state penitentiary for his defiance.

Max Pavesic, along with 14 others, took a train from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi on July 30, 1961. They were attempting to overwhelm the local jail system. When they got off the train they went into the “wrong” waiting rooms and were quickly arrested. He spent about a month in the penitentiary.

The Freedom Riders in the summer of ’61 drew nationwide attention to discrimination in the South. Their peaceful protests were often met with violence, sometimes with the KKK joining local police in confronting them. By November of that year the ICC issued a ruling reflecting earlier Supreme Court decisions against discrimination in public transportation. The Freedom Riders inspired thousands of others to take direct civil action in the civil rights movement.

Edward Kale's mugshot.

Edward Kale's mugshot.  Max Pavesic's mugshot.

Max Pavesic's mugshot.

Published on September 04, 2021 04:00

September 3, 2021

Boise's First Car Crash

The 1907 headline read “Buzz Wagon Parties Now a Fad.” The Idaho Statesman hadn’t yet settled on what to call automobiles. “Buzz wagon” didn’t catch on, fading as fast as the fad.

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst

The article was about the new trend in Boise of simply gathering people together to go for a ride in an automobile. There were only 22 personal vehicles in town, but even those who could not afford one of the infernal machines could rent one for an afternoon buzz.

In 1907 Boise already had its first auto livery and garage. It was started the year before by A.G. Randall. What Boise didn’t have was a single street designed for a horseless carriage. There were certain streets, though, that pleased autoists more than others. Warm Springs Avenue topped the list. There were well-beaten paths on either side of the trolley tracks on Warm Springs that offered a smooth ride to those whipping along at six miles per hour, the speed limit in the city. There were rumors that some exceeded that break-neck speed, though proving it was difficult. The city did not yet have a patrol car.

Even with the occasional scofflaw cranking their car up to jogging speed, there was little concern. Boise had not yet seen its first automobile accident. Oh, there was the time M. Knox, chief engineer of the Boise and Interurban, tangled with an auto. It spooked his horse, which threw him off and underneath the machine. He came away with a severe sprain. There was no actual collision, though, so it didn’t count.

In July of 1908 the Statesman was reporting that more women were being seen behind the wheels of automobiles. Reporter Eva Hunt Dockery likened the development to an infection she called “microbus automobubious.” There were by then 25 machines “whirling” around the city. Some of them were pricey, running upwards of $4,000, the equivalent of about $100,000 in todays dollars. They were beginning to be popular with doctors.

Still, no accidents in Boise in 1909. Automobile crashes that resulted in injury were such a new thing that local papers were reporting on out-of-state crashes. It was front page news when a man from Boise was slightly injured in a car crash in Brooklyn in which one man was killed.

Boise’s run of good luck couldn’t last forever. March 13, 1909 was the ominous day when an automobile accident took place in the city. The Statesman covered it in gritty detail. Sixteen-year-old Robert Shaw was at the wheel crossing a bridge over an irrigation ditch on Broadway when a pedestrian stepped out in front of him. Shaw blasted the horn, then yanked the steering wheel right, but the pedestrian started in that direction. So, Shaw yanked the wheel left only to have the pedestrian—perhaps taking a cue from local squirrels—move to the left. Careening along at as much as six miles per hour, young Shaw saw the only way to miss the man was to crash through the wooden guardrail of the bridge.

The Winton touring car, valued at $3500, plunged through the barrier and turned turtle, landing upside down in the ditch. The passengers—four in all, including Shaw’s father—fell out into the ditch, which was dry. None came away from the encounter with even a bruise.

Shaw’s father praised the young man’s choice of running off the bridge to avoid running over the pedestrian. He was quoted as saying “I cannot imagine a more serious problem than that which confronted my young son, and I am mighty proud of the pluck and level-headedness which he displayed.”

To confirm it for the history books, the paper ended the article with, “This is the first auto accident to be recorded among the many machines owned in the city.”

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst

Sisters June and Marsh Nicholes cruise the streets of Boise circa 1915. Note the squeeze bulb horn on the driver’s right. Photo courtesy of Chris Hoalst

Published on September 03, 2021 04:00

September 2, 2021

The Fosbury Flop

Idaho has a claim on a sport-changing Olympian. Or, maybe he has a claim on Idaho. When Dick Fosbury won the gold medal in the 1968 Olympics he hailed from Oregon. But in 1977, he moved to Ketchum where he still lives. He and a partner established Galena Engineering in 1978. He ran for a seat in the Idaho Legislature in 2014 against incumbent Steve Miller, but lost that race.

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Winning an Olympic gold medal comes with its own notoriety. When you break the Olympic record and do so in a totally unconventional way, the notoriety is exponential. Fosbury’s sport was the high jump. His innovation, known today as the Fosbury Flop, was to go over the bar backwards, head-first, curving his body over and kicking his legs up in the air at the end of the jump, landing on his back. It was awkward looking. Maybe it even looked impossible, but it worked. Fosbury cleared 7 feet 4 ½ inches in Mexico City for a new Olympic record.

So, why hadn’t jumpers tried this before? Well, someone has to be first. Also, for decades preceding Fosbury’s innovation a jump like that would have been dangerous, almost guaranteeing injury. What made it possible in Fosbury’s time was the wide-spread use of thick foam pads as a landing site. Prior to that jumpers were landing in sawdust or wood chips.

The art used to illustrate this post is by Alan Siegrist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)], via Wikimedia Commons

Published on September 02, 2021 04:00

September 1, 2021

The Atomic Plane

What if you had an airplane that could circle the globe for years? That question intrigued military planners in the 1940s so much that the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS), near Idaho Falls, set to work building one. It would run on atomic power, you see.

The atomic airplane would weigh 300 tons, stretch 205 feet long and measure 136 feet from wingtip to wingtip. Big, but smaller than a 747.

The plane was a joint project of the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission that began in in 1946. The goal was to come up with a practical airplane that could fly 15,000 miles without having to land.

They built a big earth-shielded hangar for the plane. The photo shows construction and the completed hangar, which last I knew was being used for manufacturing tank armor.

That the plane’s hangar is being used for some other purpose is a clue about the plane itself. They did successfully test twin nuclear engines, but at 30 feet high they were a tad big for airplanes. Miniaturization might have been possible, eventually, if the project weren’t shelved in the early 60s. Technological problems, such shielding the pilots, weren’t what killed it. Fears that such a plane would eventually crash, making the accident site uninhabitable, brought it down before it ever went up, and before a prototype had been built.

Today, you can see the two Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment reactors, used in the effort to build an atomic-powered airplane. They sit in front of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I Atomic Museum at the site near Arco.

By the way the NRTS became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), then the Idaho National Lab (INL). It retains the latter designation today. Many people in eastern Idaho just call it The Site, rather than keep up with the acronyms.

Information about the nuclear plane comes largely from Susan Stacy’s book Proving the Principle, a History of the National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, 1949-1999 .

The atomic plane hanger under construction.

The atomic plane hanger under construction.  Artist's rendering of the plane.

Artist's rendering of the plane.

The atomic airplane would weigh 300 tons, stretch 205 feet long and measure 136 feet from wingtip to wingtip. Big, but smaller than a 747.

The plane was a joint project of the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission that began in in 1946. The goal was to come up with a practical airplane that could fly 15,000 miles without having to land.

They built a big earth-shielded hangar for the plane. The photo shows construction and the completed hangar, which last I knew was being used for manufacturing tank armor.

That the plane’s hangar is being used for some other purpose is a clue about the plane itself. They did successfully test twin nuclear engines, but at 30 feet high they were a tad big for airplanes. Miniaturization might have been possible, eventually, if the project weren’t shelved in the early 60s. Technological problems, such shielding the pilots, weren’t what killed it. Fears that such a plane would eventually crash, making the accident site uninhabitable, brought it down before it ever went up, and before a prototype had been built.

Today, you can see the two Heat Transfer Reactor Experiment reactors, used in the effort to build an atomic-powered airplane. They sit in front of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-I Atomic Museum at the site near Arco.

By the way the NRTS became the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), then the Idaho National Lab (INL). It retains the latter designation today. Many people in eastern Idaho just call it The Site, rather than keep up with the acronyms.

Information about the nuclear plane comes largely from Susan Stacy’s book Proving the Principle, a History of the National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, 1949-1999 .

The atomic plane hanger under construction.

The atomic plane hanger under construction.  Artist's rendering of the plane.

Artist's rendering of the plane.

Published on September 01, 2021 04:00

August 31, 2021

The Just Brother License Plate Caper

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Did I tell you how much I love potatoes? Love ‘em. Not so much on my license plates, though. So, in the late 1980s my brother, Kent Just, and I set out to give Idahoans a choice. I located the company that made the reflective material used on the license plates at that time and learned that you could buy it in strips. I ordered a roll of the stuff and had slogans printed on it in the same size, font, and color as the slogan on the license plates. Buyers could peel off the paper on the back and stick the new slogan over “Famous Potatoes.” We sold them for a couple of bucks through Stinker Stations. You could pick from “Famous Potholes,” “The Whitewater State,” and several others.

Kent acted as the front man on this project, because I was working for the State of Idaho at the time and was a little unsure about how my employer would take this little prank. We got publicity for the project in papers from Washington State to Washington DC. Some of the articles made it sound like we had a factory cranking these out by the thousands. I had a roll of stickers and a pair of scissors.

Encouraging people to put an unauthorized sticker on a license plate ruffled the feathers of the folks over at Idaho State Police HQ. They made noises about it sufficient enough to convince us to stop selling them. We were certain we were on solid legal ground because the US Supreme Court had already ruled that it was legal to cover up a license plate slogan in the name of free speech (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die”). Still, it didn’t seem worthwhile to hire a lawyer for a $150 joke. We’d had our fun, and we’d already made our money back.

Kent passed away in 2017. I know he wouldn’t mind my adding this little footnote to a footnote in Idaho history. I can hear his way-too-loud laugh right now. Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Did I tell you how much I love potatoes? Love ‘em. Not so much on my license plates, though. So, in the late 1980s my brother, Kent Just, and I set out to give Idahoans a choice. I located the company that made the reflective material used on the license plates at that time and learned that you could buy it in strips. I ordered a roll of the stuff and had slogans printed on it in the same size, font, and color as the slogan on the license plates. Buyers could peel off the paper on the back and stick the new slogan over “Famous Potatoes.” We sold them for a couple of bucks through Stinker Stations. You could pick from “Famous Potholes,” “The Whitewater State,” and several others.

Kent acted as the front man on this project, because I was working for the State of Idaho at the time and was a little unsure about how my employer would take this little prank. We got publicity for the project in papers from Washington State to Washington DC. Some of the articles made it sound like we had a factory cranking these out by the thousands. I had a roll of stickers and a pair of scissors.

Encouraging people to put an unauthorized sticker on a license plate ruffled the feathers of the folks over at Idaho State Police HQ. They made noises about it sufficient enough to convince us to stop selling them. We were certain we were on solid legal ground because the US Supreme Court had already ruled that it was legal to cover up a license plate slogan in the name of free speech (New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die”). Still, it didn’t seem worthwhile to hire a lawyer for a $150 joke. We’d had our fun, and we’d already made our money back.

Kent passed away in 2017. I know he wouldn’t mind my adding this little footnote to a footnote in Idaho history. I can hear his way-too-loud laugh right now.

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Idaho was far more famous for its potatoes than its potholes, but who could resist?

Published on August 31, 2021 04:00

August 30, 2021

Just Fishing

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel, Keeping Private Idaho . Today I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

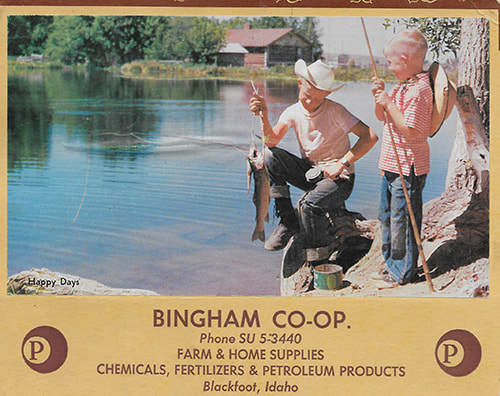

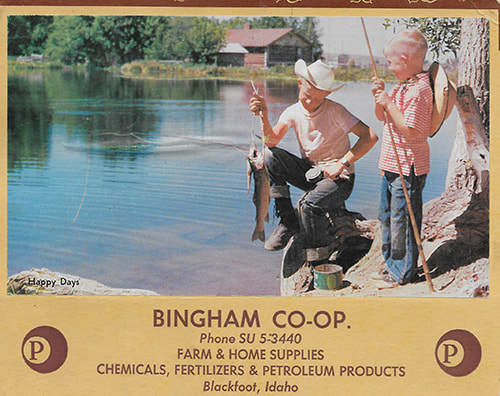

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

This photo, from Idaho Farmer, circa 1959, shows my mother, Iris, my father, Chick, and brother Kent digging worms. I'm eating donut, or something, in the background. My mom wrote an article about the fish pond for the magazine. By the way, the pond, though smaller now, still exists. It is not open for fishing.

This photo, from Idaho Farmer, circa 1959, shows my mother, Iris, my father, Chick, and brother Kent digging worms. I'm eating donut, or something, in the background. My mom wrote an article about the fish pond for the magazine. By the way, the pond, though smaller now, still exists. It is not open for fishing.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

We all have our own Idaho. I wrote about that a few years back in my novel, Keeping Private Idaho . Today I’m going to introduce you to mine.

Along about 1956 my father, who we called Pop, noticed that the configuration of ditches near the house on our family ranch outside of Blackfoot made three sides of a rectangle. I still remember him scraping up dirt with a squat little Ford tractor, pushing it up into what would become a dike along that fourth side.

Pop’s father and grandfather had built a major part of the canal system in Eastern Idaho, so he knew a little bit about making water do what he wanted it to. Usually that meant setting canvas dams in ditches and scraping off the high spots so that a field of alfalfa could get water. But while he was tromping around in waders with a shovel, pointing the way for water, he was thinking about his all-time favorite activity: fishing.

When pop diverted the water into what now had dikes on four sides, we saw his vision come to life. He had created a fish pond, about an acre in size. My brothers and I watched as the tankers came from Springfield with loads of rainbow trout, dumping them into the pond, which had quickly acquired moss, and bugs, and frogs.

Pop called his big idea Chick Just’s Trout Ranch. He had orange signs made that he could tack up on fence posts so people could find their way to the ranch. He charged by the pound for fish they caught. No charge if you didn’t catch anything. But they always caught fish. That was his joy. He liked nothing better than to see a kid catch her first trout.

So, paradise for me. I didn’t care much about fishing, but I cared for nothing more than I cared for that pond. It was my world; one which I could pole across in a skiff pretending I was Huck Finn, and swim in trying not to drown. I caught a million tadpoles and watched them turn into frogs, and chased dragonflies that were enemy helicopters.

That pond was the center of my life growing up. It must have occupied 50 years of my childhood. Yet, when I do the math now, I’m stunned by it. Pop died in 1960. We moved into town in 1961. Five years, not 50.

It was so idyllic for a kid you’d think I was making it up. But I have a picture. This one appeared on calendars and in magazines promoting Idaho for three or four years. It’s of me, the cute one, with my older brother, Kent. In the background, you can just make out our log house across the pond. My private Idaho. What does yours look like?

This photo, from Idaho Farmer, circa 1959, shows my mother, Iris, my father, Chick, and brother Kent digging worms. I'm eating donut, or something, in the background. My mom wrote an article about the fish pond for the magazine. By the way, the pond, though smaller now, still exists. It is not open for fishing.

This photo, from Idaho Farmer, circa 1959, shows my mother, Iris, my father, Chick, and brother Kent digging worms. I'm eating donut, or something, in the background. My mom wrote an article about the fish pond for the magazine. By the way, the pond, though smaller now, still exists. It is not open for fishing.

Published on August 30, 2021 04:00

August 29, 2021

Just Politics

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Nels Just was elected in 1899 as one of Bingham County’s early commissioners. That was his only elected office, but he was involved in politics most of his life, attending several state Democratic conventions, and spending considerable time in Boise during legislative sessions.

Nels’ eldest son, James Just, was elected to the Idaho State Senate in 1934, serving through 1938. John Corlett, who wrote about politics for the Idaho Statesman for decades once told me that my grandfather, James Just, had a habit of putting his thumbs through his suspenders while speaking from the podium, and rocking back and forth on his feet. For this habit he was dubbed “Jumpin’ Jimmy Just” by reporters.

Both Nels and James Just were friends with Fred T. Dubois, who was a U.S. Senator from Idaho for many years. James also palled around a bit with Glenn Taylor, who served one term in the Senate from Idaho.

Rinda Just, my spouse served as a Boise city planning and zoning commissioner for ten years. I served for a time on that commission as well, and I’m currently running for the District 15 state senate seat. If elected I vow not to acquire a nickname for my antics on the floor of the senate. One Jumpin’ Jimmy is enough, though my first name is James. I go by my middle name. Idaho State Senator James Just.

Idaho State Senator James Just.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Nels Just was elected in 1899 as one of Bingham County’s early commissioners. That was his only elected office, but he was involved in politics most of his life, attending several state Democratic conventions, and spending considerable time in Boise during legislative sessions.

Nels’ eldest son, James Just, was elected to the Idaho State Senate in 1934, serving through 1938. John Corlett, who wrote about politics for the Idaho Statesman for decades once told me that my grandfather, James Just, had a habit of putting his thumbs through his suspenders while speaking from the podium, and rocking back and forth on his feet. For this habit he was dubbed “Jumpin’ Jimmy Just” by reporters.

Both Nels and James Just were friends with Fred T. Dubois, who was a U.S. Senator from Idaho for many years. James also palled around a bit with Glenn Taylor, who served one term in the Senate from Idaho.

Rinda Just, my spouse served as a Boise city planning and zoning commissioner for ten years. I served for a time on that commission as well, and I’m currently running for the District 15 state senate seat. If elected I vow not to acquire a nickname for my antics on the floor of the senate. One Jumpin’ Jimmy is enough, though my first name is James. I go by my middle name.

Idaho State Senator James Just.

Idaho State Senator James Just.

Published on August 29, 2021 04:00

August 28, 2021

Artists from Pioneer Stock

The Just-Reid family is celebrating the Sesquicentennial Plus One of Nels and Emma Just settling in the Blackfoot River Valley near Blackfoot. We had planned to celebrate last year, but that got put on hold along with so much else when COVID hit.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Yesterday I wrote about Agnes Just Reid’s book Letters of Long Ago. Today we have a side note on that story.

As you may remember when Nels and Emma drove a team of oxen some 80 miles each way in 1870 to get married, Emma’s first son, Fred Bennett went along for the ride. He was just shy of two years old.

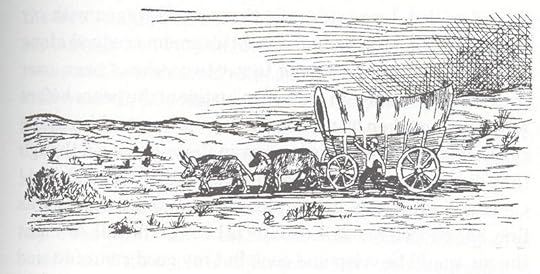

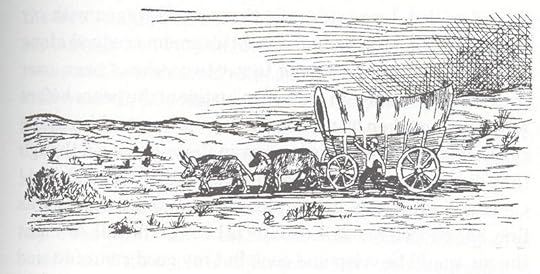

Here’s a sketch from Letters of Long Ago that illustrated that first chapter of the book.

Each of the chapters in the book had a sketch by Mabel Bennett, the daughter of the two-year-old who rode along to Malad City.

Each of the chapters in the book had a sketch by Mabel Bennett, the daughter of the two-year-old who rode along to Malad City.

Mabel became Mabel Bennett Hutchinson in 1927 when she married Milon Hutchinson, who grew up near Firth. They settled in California where Milon was a woodworking craftsman. Mabel became well known for her watercolors over the years, painting regional works that were shown all over California. After painting for 20 years, she decided she had nothing more to say in that medium. She experimented with abstracts in the 50s, then in the 1960s she began sculpting with scraps of wood from Milon’s shop. Her totems were widely shown and well received. During this period, she and Milon began creating massive door sculptures. Her doors have sold for as much as $35,000. Several Hollywood celebrities bought them for their homes. Science fiction writer Harlan Ellison had one in his legendary treehouse. He and Mabel kept up an intellectual correspondence for several years.

Barrio Afternoon, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.

Barrio Afternoon, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.  Waiting for the Townsend Plan, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.

Waiting for the Townsend Plan, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.  Mabel with one of her door sculptures. Mabel grew up in Idaho but found her artistic success in California. Another family member with Idaho roots is making a name for himself in the art world right now. Brent Cotton captured the family homestead in magic hour, winter light in the oil below.

Mabel with one of her door sculptures. Mabel grew up in Idaho but found her artistic success in California. Another family member with Idaho roots is making a name for himself in the art world right now. Brent Cotton captured the family homestead in magic hour, winter light in the oil below.

In honor of Sesquicentennial Plus One, I’m devoting the Speaking of Idaho blog to my family’s history during August.

Yesterday I wrote about Agnes Just Reid’s book Letters of Long Ago. Today we have a side note on that story.

As you may remember when Nels and Emma drove a team of oxen some 80 miles each way in 1870 to get married, Emma’s first son, Fred Bennett went along for the ride. He was just shy of two years old.

Here’s a sketch from Letters of Long Ago that illustrated that first chapter of the book.

Each of the chapters in the book had a sketch by Mabel Bennett, the daughter of the two-year-old who rode along to Malad City.

Each of the chapters in the book had a sketch by Mabel Bennett, the daughter of the two-year-old who rode along to Malad City.Mabel became Mabel Bennett Hutchinson in 1927 when she married Milon Hutchinson, who grew up near Firth. They settled in California where Milon was a woodworking craftsman. Mabel became well known for her watercolors over the years, painting regional works that were shown all over California. After painting for 20 years, she decided she had nothing more to say in that medium. She experimented with abstracts in the 50s, then in the 1960s she began sculpting with scraps of wood from Milon’s shop. Her totems were widely shown and well received. During this period, she and Milon began creating massive door sculptures. Her doors have sold for as much as $35,000. Several Hollywood celebrities bought them for their homes. Science fiction writer Harlan Ellison had one in his legendary treehouse. He and Mabel kept up an intellectual correspondence for several years.

Barrio Afternoon, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.

Barrio Afternoon, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.  Waiting for the Townsend Plan, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.

Waiting for the Townsend Plan, by Mabel Bennett Hutchinson.  Mabel with one of her door sculptures. Mabel grew up in Idaho but found her artistic success in California. Another family member with Idaho roots is making a name for himself in the art world right now. Brent Cotton captured the family homestead in magic hour, winter light in the oil below.

Mabel with one of her door sculptures. Mabel grew up in Idaho but found her artistic success in California. Another family member with Idaho roots is making a name for himself in the art world right now. Brent Cotton captured the family homestead in magic hour, winter light in the oil below.

Published on August 28, 2021 04:00