Rick Just's Blog, page 111

November 7, 2021

Sunday Rest (Tap to read the story)

I did the research for this column on a Sunday. I wrote it on another Sunday. It will appear on yet another Sunday. Does that make me a scofflaw?

No, not in 2021. In 1907 the answer would not have been so clear.

Many Idahoans would rather the state name not even appear in the same sentence as California. It will appear that way here, twice. Idaho and California were the last two states in the nation that did not have a Sunday Rest law on the books in 1907. That was soon to change.

Sunday Rest laws were put in statute to codify a day of rest from secular labor. The International Reform Bureau was a group promoting such laws nationwide, and Idaho was in their sights. Dr. G.L. Tufts, of Portland, was the group’s lead lobbyist. He took his job seriously enough to get arrested for it.

Dr. Tufts became the first to test a law then recently passed by the Idaho Legislature that prohibited lobbying in the statehouse. Tufts was arrested on a Wednesday after repeated warnings that his conversations with lawmakers were prohibited. Presiding over the case a Justice Savidge released the man that Friday on the grounds that “Your thought (was) kindly and brotherly, nothing else, and your motive philanthropic. Your intention was far from anything criminal and you may go on your way.”

The law prohibiting lobbying didn’t last, perhaps due in part to this quick dismissal.

The bill Dr. Tufts lobbied for got considerable support from the citizenry in the form of petitions. As a sample, there were 41 signatures from St. Anthony, 126 from Boise, and, notably, 310 from Kellogg. The Silver Valley, which includes Kellogg, was deeply torn by the proposed law. Mine owners pointed out the hardship of shutting down their operations one day each week and missing out on the soaring silver prices at the time. Bar owners, especially in Wallace, openly vowed to flout the law if it passed.

It passed, and now it was up to law enforcement to see that citizens adhered to it. Whatever that meant. These days Pandora is a music streaming service. Back then it was a proverbial box filled with squirming issues released upon passage of the Sunday Rest law. If people couldn’t gather for a play on Sunday, could they gather at church? Most agreed they could, but in Boise the line between entertainment and religion was blurred when the county prosecutor shut down a Passion Play on a Sunday at the YMCA for violating the law.

As Jimmy Buffett once sang, “There’s a thin line between Saturday night and Sunday morning.” True to their word, bar owners in Wallace refused to shut down when Saturday nights rolled into the wee hours of Sunday. They were arrested and rearrested. They tried closing up the front of their establishments and sneaking people in the back.

Enforcement of the law was often lax. When three saloon keepers in Cottonwood stood trial, they were sentenced to spend one minute in the county jail at Grangeville.

In Boise the manager of Riverside Park was arrested for showing a theatrical production on a Sunday. The law specified a $100 fine for such an affront. Other Boiseans were arrested for operating a shoeshining stand, running a steam bath, and for selling produce. The prosecutor in Ada County got complaints about the Boise Commercial club and the Elks’ club conducting business over the bar on Sundays. He determined that since they were private enterprises the law did not apply.

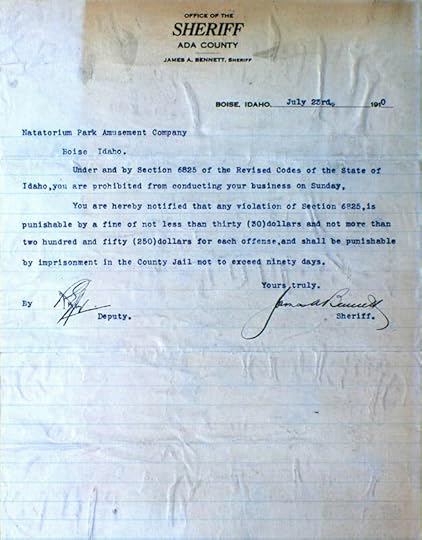

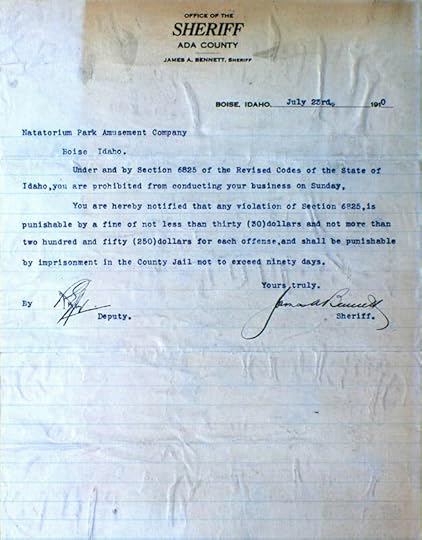

And that was the rub. Deciding when the law applied and when it didn’t became an endless question. The manager at the Natatorium and the White City Amusement Park made his own determination about what could operate and what couldn’t. Predictably he guessed wrong, at least according to the Ada County Prosecutor.

In July of 1910, the Nat manager, G.W. Hull was arrested for running a scenic railroad around the White City Amusement Park on a Sunday. An immediate uproar commenced, with people questioning the fairness of arresting a train operator while leaving operators of the Interurban trolley line free to take people all around the valley on scenic excursions.

The scenic railroad arrest became a test case that went to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court ruled in favor of Hull, stating that amusements not “immoral, corrupt or boisterous” did not break the law.

Interpretations and misinterpretations continued for years with enforcement growing increasingly lax. The Idaho Legislature finally repealed the Sunday Rest law in 1939. So, today you’re welcome to go to church, watch a Passion Play—or any kind of play—as well as put in a hard day’s labor. You’re also welcome to rest.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

No, not in 2021. In 1907 the answer would not have been so clear.

Many Idahoans would rather the state name not even appear in the same sentence as California. It will appear that way here, twice. Idaho and California were the last two states in the nation that did not have a Sunday Rest law on the books in 1907. That was soon to change.

Sunday Rest laws were put in statute to codify a day of rest from secular labor. The International Reform Bureau was a group promoting such laws nationwide, and Idaho was in their sights. Dr. G.L. Tufts, of Portland, was the group’s lead lobbyist. He took his job seriously enough to get arrested for it.

Dr. Tufts became the first to test a law then recently passed by the Idaho Legislature that prohibited lobbying in the statehouse. Tufts was arrested on a Wednesday after repeated warnings that his conversations with lawmakers were prohibited. Presiding over the case a Justice Savidge released the man that Friday on the grounds that “Your thought (was) kindly and brotherly, nothing else, and your motive philanthropic. Your intention was far from anything criminal and you may go on your way.”

The law prohibiting lobbying didn’t last, perhaps due in part to this quick dismissal.

The bill Dr. Tufts lobbied for got considerable support from the citizenry in the form of petitions. As a sample, there were 41 signatures from St. Anthony, 126 from Boise, and, notably, 310 from Kellogg. The Silver Valley, which includes Kellogg, was deeply torn by the proposed law. Mine owners pointed out the hardship of shutting down their operations one day each week and missing out on the soaring silver prices at the time. Bar owners, especially in Wallace, openly vowed to flout the law if it passed.

It passed, and now it was up to law enforcement to see that citizens adhered to it. Whatever that meant. These days Pandora is a music streaming service. Back then it was a proverbial box filled with squirming issues released upon passage of the Sunday Rest law. If people couldn’t gather for a play on Sunday, could they gather at church? Most agreed they could, but in Boise the line between entertainment and religion was blurred when the county prosecutor shut down a Passion Play on a Sunday at the YMCA for violating the law.

As Jimmy Buffett once sang, “There’s a thin line between Saturday night and Sunday morning.” True to their word, bar owners in Wallace refused to shut down when Saturday nights rolled into the wee hours of Sunday. They were arrested and rearrested. They tried closing up the front of their establishments and sneaking people in the back.

Enforcement of the law was often lax. When three saloon keepers in Cottonwood stood trial, they were sentenced to spend one minute in the county jail at Grangeville.

In Boise the manager of Riverside Park was arrested for showing a theatrical production on a Sunday. The law specified a $100 fine for such an affront. Other Boiseans were arrested for operating a shoeshining stand, running a steam bath, and for selling produce. The prosecutor in Ada County got complaints about the Boise Commercial club and the Elks’ club conducting business over the bar on Sundays. He determined that since they were private enterprises the law did not apply.

And that was the rub. Deciding when the law applied and when it didn’t became an endless question. The manager at the Natatorium and the White City Amusement Park made his own determination about what could operate and what couldn’t. Predictably he guessed wrong, at least according to the Ada County Prosecutor.

In July of 1910, the Nat manager, G.W. Hull was arrested for running a scenic railroad around the White City Amusement Park on a Sunday. An immediate uproar commenced, with people questioning the fairness of arresting a train operator while leaving operators of the Interurban trolley line free to take people all around the valley on scenic excursions.

The scenic railroad arrest became a test case that went to the Idaho Supreme Court. The court ruled in favor of Hull, stating that amusements not “immoral, corrupt or boisterous” did not break the law.

Interpretations and misinterpretations continued for years with enforcement growing increasingly lax. The Idaho Legislature finally repealed the Sunday Rest law in 1939. So, today you’re welcome to go to church, watch a Passion Play—or any kind of play—as well as put in a hard day’s labor. You’re also welcome to rest.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

The manager of the Natatorium Park Amusement Company got a warning before his arrest for violating Idaho’s Sunday Rest law. Image from the Bob Hartman Collection.

Published on November 07, 2021 04:00

November 6, 2021

Train Wreckers (Tap to read)

In the early days of railroads there was a subset of law breakers called Train Wreckers. They were sometimes involved in union activities, trying to derail a train as part of a labor action, but most often robbery was the motive. The activity inspired hundreds of headlines and at least one stage production.

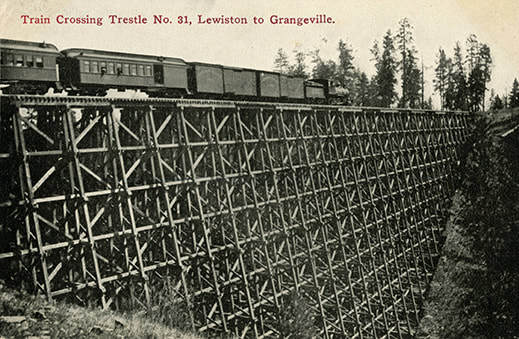

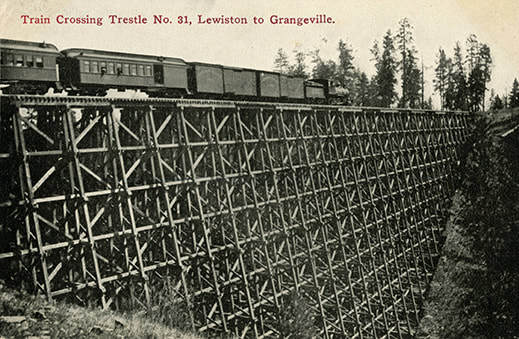

The three most popular methods of wrecking a train were, first, to take out a trestle, which would send a locomotive plunging. Second, was the removal of frogs, the structure that ties two rail ends together. This could be accompanied by the shifting of at least one of the rails. Third, vandals would put some obstruction on the track, ranging from logs to boulders. Derailing the train was often the result, but simply stopping it would do nearly as well.

In 1890 newspaper readers in the Treasure Valley followed the story of an attempt to wreck the Montreal Express near Albany New York. In 1891, wreckers were foiled when someone found a piece of iron fastened to tracks near Minneapolis. The plotters were caught and confessed they were planning to rob the disabled train.

In September 1892, Passenger Train Number 8 was derailed west of Osage, Missouri. Four men were killed in the attempted robbery of a million dollars on board the train. Thirty-five men, women and children were injured. That same year a train wreck was foiled in Coon Rapids, Iowa. There were alleged Mafia ties to that one.

In 1893, train wreckers bumped the Vandela Express from its tracks near Brazil, Indiana. In February 1894 a train was derailed near Houston, and the wreck robbed in a hail of bullets. That same year there were train wreckers in Colorado and California. And Idaho.

Some lament that Idaho is late to every party, but this wasn’t one to which anyone sought an invitation. It came by way of rail.

On a September day in 1894 a west-bound train chugged out of Mountain Home across the desert toward Nampa. The train carried passengers, mail, and freight. Things were progressing routinely until the engineer squinted into the distance. There was something on the track. That something was moving toward them. It was a handcar with two men aboard pumping furiously into the teeth of the barreling locomotive. The engineer pulled hard on the brake lever, raising a hideous shriek from steel wheels sliding on steel rails.

The sudden action threw passengers from their seats. When the train came to a stop the travelers piled out of the cars to see what was up.

Aboard the handcar, now snugged up to the cowcatcher, was the railroad section foreman and a section hand, out of breath from pumping.

In words you are welcome to color with your imagination the engineer inquired as to the purpose of putting a handcar in the path of a speeding train. In fact, the section foreman had an excellent answer. He had been on a routine inspection of the tracks in his section near Owyhee Station when he noticed that someone had removed the frogs and fish plates to misalign a track section that ran across a gully. The next train to hit that trestle would have plunged 45 feet into the channel with cars piling behind it like loose dominos.

The railroad men had worked feverishly to repair the track before the scheduled train could hit the bad spot. Repaired though it was, the men thought it would be prudent to warn the coming train to take it slow and careful, and not just out of an abundance of caution about the repair. While working to fix the vandalized section the railroad men had spotted a man on horseback, well-armed, watching their progress from a nearby hilltop.

Fearing there might be more mischief ahead, the train crew prepared the passengers for a possible attack, having them crouch low on the floor. It was about then that the aforementioned horseman appeared as a silhouette on a ridgetop. As it happened, the assistant superintendent of the Oregon Short Line—so named because it was the shortest route between Wyoming and Oregon—was on board. S.S. Morris walked out to have a chat with the rider. The man declined the invitation by spurring his horse and disappearing behind the rise.

The slow, careful chug into Nampa with eyeballs examining the rails along the way, was accompanied at one point by the mystery rider. He galloped alongside the train, showing off his rifle in an aggressive way, but never firing a shot. It must have been an act of frustration.

The train rolled away, but the rider pulled up and turned his horse back toward Owyhee station where he found the section foreman and his section hand moving the handcar to a siding. The mystery rider began sending bullets in their direction. The rail men, no fools they, took cover. The bullets left a mark on the handcar, but the men were unharmed. The would-be robber finally rode off.

As soon as the train rolled into Nampa law enforcement got involved. Since the potential robbery of a mail car was involved, that brought in the U.S. Marshall. A renowned Indian fighter named Orlando “Rube” Robbins was dispatched to bring the perpetrator(s) to justice. Rube and his posse set out into Owyhee County with the best wishes and high hopes of the gentle people of the region. The Statesman opined, “(U.S.) Marshal Crutcher is fortunate in having been able to lay hands at once on Rube Robbins and start him on the trail. Robbins is like a bloodhound when tracking a criminal, and the fact that his game would have only a few hours start makes speedy capture exceedingly probable.”

Rube and his crew did find some promising tracks to follow, just as a thunderstorm sluiced them away. In talking with locals they uncovered a precious lead, which The Statesman duly reported.

In stacked headlines, common at the time, the paper blared:

NOTORIOUS BANDIT HERE

Thought to Be the Leader of the

Train Wreckers

OLD HAND AT THE BUSINESS

Charles Somers, a Famous Outlaw.

Known to Have Been in This

Vicinity Recently. Somers was the prime suspect because, “(he) is an outlaw who has been concerned in several train robberies.” He had been arrested by Pinkerton agents a year and a half earlier for robbing a train in California, tried, and sentenced to prison. Then he escaped.

It was reported that Somers had an aunt living in Boise, whom he had recently visited. He had boasted to someone that he had eaten at the Palace restaurant at the table right next to the chief of police!

Excitement about the train wrecker or wreckers and imminent capture of same soon dwindled as the posse came back without a prisoner in tow.

Somers, the main suspect, took some air out of the balloon when he wrote to The Statesman from Toronto, Canada. “I see I am charged with being the leader of bandits who recently attempted to wreck a train near Boise,” he wrote. “And also, with being an old hand at the business. Parties who perpetrated the recent crime deserve no consideration from the pursuing posse and would get none from me if I were a member of it.”

The accused went on to say, “If it will satisfy the curiosity of your readers to know the truth of the report that I ate supper at the same table in the Spanish restaurant in Boise with the chief of police let me end the suspense by saying yes. Such was the case, but is was April, not recently as claimed. I think I could go there and do so again with impunity. As to being a desperate man, I will say I am as docile as a kitten, but confess such charges in your article are enough to drive a man to desperation.”

Somers asked but one thing of The Statesman. Could they at least spell his name right? It was Summers, not Somers.

So, with little more gained from the whole incident than a spelling correction the story of the very nearly almost train wreck and robbery of 1894 faded away like a desert flower past its prime.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

The three most popular methods of wrecking a train were, first, to take out a trestle, which would send a locomotive plunging. Second, was the removal of frogs, the structure that ties two rail ends together. This could be accompanied by the shifting of at least one of the rails. Third, vandals would put some obstruction on the track, ranging from logs to boulders. Derailing the train was often the result, but simply stopping it would do nearly as well.

In 1890 newspaper readers in the Treasure Valley followed the story of an attempt to wreck the Montreal Express near Albany New York. In 1891, wreckers were foiled when someone found a piece of iron fastened to tracks near Minneapolis. The plotters were caught and confessed they were planning to rob the disabled train.

In September 1892, Passenger Train Number 8 was derailed west of Osage, Missouri. Four men were killed in the attempted robbery of a million dollars on board the train. Thirty-five men, women and children were injured. That same year a train wreck was foiled in Coon Rapids, Iowa. There were alleged Mafia ties to that one.

In 1893, train wreckers bumped the Vandela Express from its tracks near Brazil, Indiana. In February 1894 a train was derailed near Houston, and the wreck robbed in a hail of bullets. That same year there were train wreckers in Colorado and California. And Idaho.

Some lament that Idaho is late to every party, but this wasn’t one to which anyone sought an invitation. It came by way of rail.

On a September day in 1894 a west-bound train chugged out of Mountain Home across the desert toward Nampa. The train carried passengers, mail, and freight. Things were progressing routinely until the engineer squinted into the distance. There was something on the track. That something was moving toward them. It was a handcar with two men aboard pumping furiously into the teeth of the barreling locomotive. The engineer pulled hard on the brake lever, raising a hideous shriek from steel wheels sliding on steel rails.

The sudden action threw passengers from their seats. When the train came to a stop the travelers piled out of the cars to see what was up.

Aboard the handcar, now snugged up to the cowcatcher, was the railroad section foreman and a section hand, out of breath from pumping.

In words you are welcome to color with your imagination the engineer inquired as to the purpose of putting a handcar in the path of a speeding train. In fact, the section foreman had an excellent answer. He had been on a routine inspection of the tracks in his section near Owyhee Station when he noticed that someone had removed the frogs and fish plates to misalign a track section that ran across a gully. The next train to hit that trestle would have plunged 45 feet into the channel with cars piling behind it like loose dominos.

The railroad men had worked feverishly to repair the track before the scheduled train could hit the bad spot. Repaired though it was, the men thought it would be prudent to warn the coming train to take it slow and careful, and not just out of an abundance of caution about the repair. While working to fix the vandalized section the railroad men had spotted a man on horseback, well-armed, watching their progress from a nearby hilltop.

Fearing there might be more mischief ahead, the train crew prepared the passengers for a possible attack, having them crouch low on the floor. It was about then that the aforementioned horseman appeared as a silhouette on a ridgetop. As it happened, the assistant superintendent of the Oregon Short Line—so named because it was the shortest route between Wyoming and Oregon—was on board. S.S. Morris walked out to have a chat with the rider. The man declined the invitation by spurring his horse and disappearing behind the rise.

The slow, careful chug into Nampa with eyeballs examining the rails along the way, was accompanied at one point by the mystery rider. He galloped alongside the train, showing off his rifle in an aggressive way, but never firing a shot. It must have been an act of frustration.

The train rolled away, but the rider pulled up and turned his horse back toward Owyhee station where he found the section foreman and his section hand moving the handcar to a siding. The mystery rider began sending bullets in their direction. The rail men, no fools they, took cover. The bullets left a mark on the handcar, but the men were unharmed. The would-be robber finally rode off.

As soon as the train rolled into Nampa law enforcement got involved. Since the potential robbery of a mail car was involved, that brought in the U.S. Marshall. A renowned Indian fighter named Orlando “Rube” Robbins was dispatched to bring the perpetrator(s) to justice. Rube and his posse set out into Owyhee County with the best wishes and high hopes of the gentle people of the region. The Statesman opined, “(U.S.) Marshal Crutcher is fortunate in having been able to lay hands at once on Rube Robbins and start him on the trail. Robbins is like a bloodhound when tracking a criminal, and the fact that his game would have only a few hours start makes speedy capture exceedingly probable.”

Rube and his crew did find some promising tracks to follow, just as a thunderstorm sluiced them away. In talking with locals they uncovered a precious lead, which The Statesman duly reported.

In stacked headlines, common at the time, the paper blared:

NOTORIOUS BANDIT HERE

Thought to Be the Leader of the

Train Wreckers

OLD HAND AT THE BUSINESS

Charles Somers, a Famous Outlaw.

Known to Have Been in This

Vicinity Recently. Somers was the prime suspect because, “(he) is an outlaw who has been concerned in several train robberies.” He had been arrested by Pinkerton agents a year and a half earlier for robbing a train in California, tried, and sentenced to prison. Then he escaped.

It was reported that Somers had an aunt living in Boise, whom he had recently visited. He had boasted to someone that he had eaten at the Palace restaurant at the table right next to the chief of police!

Excitement about the train wrecker or wreckers and imminent capture of same soon dwindled as the posse came back without a prisoner in tow.

Somers, the main suspect, took some air out of the balloon when he wrote to The Statesman from Toronto, Canada. “I see I am charged with being the leader of bandits who recently attempted to wreck a train near Boise,” he wrote. “And also, with being an old hand at the business. Parties who perpetrated the recent crime deserve no consideration from the pursuing posse and would get none from me if I were a member of it.”

The accused went on to say, “If it will satisfy the curiosity of your readers to know the truth of the report that I ate supper at the same table in the Spanish restaurant in Boise with the chief of police let me end the suspense by saying yes. Such was the case, but is was April, not recently as claimed. I think I could go there and do so again with impunity. As to being a desperate man, I will say I am as docile as a kitten, but confess such charges in your article are enough to drive a man to desperation.”

Somers asked but one thing of The Statesman. Could they at least spell his name right? It was Summers, not Somers.

So, with little more gained from the whole incident than a spelling correction the story of the very nearly almost train wreck and robbery of 1894 faded away like a desert flower past its prime.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

This wasn't the train in the story, but it will help you imagine the kind of damage a train wrecker could cause.

Published on November 06, 2021 04:00

November 5, 2021

The Town Founders (Tap to read the story)

Towns in Idaho were rarely created on a whim. Most can trace their roots back to some geographical, geological, or transportation-related happenstance. Silver City, Idaho City, Florence, Bayhorse, and many others popped up because there was something nearby to mine. Idaho Falls, first called Eagle Rock, owes its location to a convenient narrowing of the Snake River where entrepreneurs could place a toll bridge. Boise came to into existence because of several factors, the nearby river, mining in the mountains, and the creation of the military Fort Boise, which provided some welcome protection from attack.

Today, we’re going to look at how Caldwell got its start. Mountain Home, Hailey, Shoshone, and Weiser got their start the same way.

Robert E. Strahorn and his wife Carrie Adell Green Strahorn—often called “Dell”—went everywhere together. Everywhere. The book Dell Strahorn wrote about their adventures is called (take a breath before you read this) Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage: a Woman's Unique Experience During Thirty Years of Path Finding and Pioneering From the Missouri to the Pacific and From Alaska to Mexico. It was published in 1911. Because of its popularity—it’s still in print today—Mrs. Strahorn is the best known of the two. Mr. Strahorn’s book, published in 1881 had a somewhat shorter title, The Resources and Attractions of Idaho Territory, for the Homeseeker, Capitalist and Tourist. It was popular at the time with Easterners dreaming of the West.

Writing about the West was Robert Strahorn’s job. The owner of Union Pacific Railroad at the time, 1877, hired him to write books and newspaper articles about how wonderful the West was in order to attract settlers and increase the fortune of said owner. His name was Jay Gould, and photos of him grace reference pages about Robber Barons not infrequently.

His boss’s alleged villainy aside, Strahorn was eager to take the publicity job, with one condition. He knew that it would require months of travelling that turned into years, so he insisted on taking his wife along. It was a good move for everyone concerned. She provided much enticing writing herself and was heavily involved with her husband in selecting sites where the Idaho and Oregon Land Development Company, closely affiliated with the Union Pacific, could purchase cheap land for the purpose of erecting railroad stations, which would in turn be the impetus for a town.

The aforementioned townsites came first. The railroad would come later.

Robert Strahorn roughly plotted out the route for the Oregon Shortline Railroad from Granger, Wyoming to Portland, Oregon, and he convinced the railroad to put in a spur to Hailey. That, 50-some years later, would give Averell Harriman the idea to create Sun Valley when he was the head of Union Pacific.

The Strahorns spent about 11 years in Idaho, buying land, laying out townsites, and sending reams of enthusiastic propaganda back East.

There is probably no town more indebted to the Strahorns than Caldwell, even if it is only for the name. The nascent berg was called Bugtown, at first, but Robert Strahorn named it after a business partner and U.S. Senator from Kansas, Alexander Caldwell.

The couple built the first home in Caldwell on Filmore Street between 7th Street and Kimball Avenue. They called it The Sunnyside Ranch, a bit of hyperbole for a 600 square foot house. Carrie Strahorn set out to civilize the new town by helping to start up its first church, a nondenominational gathering place headed by a Presbyterian minister by the name of Judson Boone. She also supported Boone when he decided to start a church-affiliated college in the bustling little town. The College of Idaho, founded in 1891, the state’s oldest private college, was the result.

Carrie Adell Green Strahorn passed away in 1925. Robert Strahorn donated funds in her name for the construction of the Strahorn Memorial Library on the campus of the College of Idaho. Today it is called Strahorn Hall and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The founding of a few Idaho towns was just a sliver in the lives of the remarkable Strahorns. Robert would continue to plot the course of railroads, and invest in mining and newspaper ventures long after the death of his wife. He lived to be 92, dying in San Francisco in 1944. He made and lost fortunes over the years. Upon his death his riches were just a memory.

Carrie Adell Green Strahorn

Carrie Adell Green Strahorn

Today, we’re going to look at how Caldwell got its start. Mountain Home, Hailey, Shoshone, and Weiser got their start the same way.

Robert E. Strahorn and his wife Carrie Adell Green Strahorn—often called “Dell”—went everywhere together. Everywhere. The book Dell Strahorn wrote about their adventures is called (take a breath before you read this) Fifteen Thousand Miles by Stage: a Woman's Unique Experience During Thirty Years of Path Finding and Pioneering From the Missouri to the Pacific and From Alaska to Mexico. It was published in 1911. Because of its popularity—it’s still in print today—Mrs. Strahorn is the best known of the two. Mr. Strahorn’s book, published in 1881 had a somewhat shorter title, The Resources and Attractions of Idaho Territory, for the Homeseeker, Capitalist and Tourist. It was popular at the time with Easterners dreaming of the West.

Writing about the West was Robert Strahorn’s job. The owner of Union Pacific Railroad at the time, 1877, hired him to write books and newspaper articles about how wonderful the West was in order to attract settlers and increase the fortune of said owner. His name was Jay Gould, and photos of him grace reference pages about Robber Barons not infrequently.

His boss’s alleged villainy aside, Strahorn was eager to take the publicity job, with one condition. He knew that it would require months of travelling that turned into years, so he insisted on taking his wife along. It was a good move for everyone concerned. She provided much enticing writing herself and was heavily involved with her husband in selecting sites where the Idaho and Oregon Land Development Company, closely affiliated with the Union Pacific, could purchase cheap land for the purpose of erecting railroad stations, which would in turn be the impetus for a town.

The aforementioned townsites came first. The railroad would come later.

Robert Strahorn roughly plotted out the route for the Oregon Shortline Railroad from Granger, Wyoming to Portland, Oregon, and he convinced the railroad to put in a spur to Hailey. That, 50-some years later, would give Averell Harriman the idea to create Sun Valley when he was the head of Union Pacific.

The Strahorns spent about 11 years in Idaho, buying land, laying out townsites, and sending reams of enthusiastic propaganda back East.

There is probably no town more indebted to the Strahorns than Caldwell, even if it is only for the name. The nascent berg was called Bugtown, at first, but Robert Strahorn named it after a business partner and U.S. Senator from Kansas, Alexander Caldwell.

The couple built the first home in Caldwell on Filmore Street between 7th Street and Kimball Avenue. They called it The Sunnyside Ranch, a bit of hyperbole for a 600 square foot house. Carrie Strahorn set out to civilize the new town by helping to start up its first church, a nondenominational gathering place headed by a Presbyterian minister by the name of Judson Boone. She also supported Boone when he decided to start a church-affiliated college in the bustling little town. The College of Idaho, founded in 1891, the state’s oldest private college, was the result.

Carrie Adell Green Strahorn passed away in 1925. Robert Strahorn donated funds in her name for the construction of the Strahorn Memorial Library on the campus of the College of Idaho. Today it is called Strahorn Hall and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The founding of a few Idaho towns was just a sliver in the lives of the remarkable Strahorns. Robert would continue to plot the course of railroads, and invest in mining and newspaper ventures long after the death of his wife. He lived to be 92, dying in San Francisco in 1944. He made and lost fortunes over the years. Upon his death his riches were just a memory.

Carrie Adell Green Strahorn

Carrie Adell Green Strahorn

Published on November 05, 2021 04:00

November 4, 2021

The 1958 Payette Plane Crash (Tap to read the story)

Flying always comes with some risk. If you’re part of the US Air Force Thunderbirds team you are certainly well aware of that.

The Thunderbirds are a demonstration squadron based at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. They perform aerial acrobatics all over the country, thrilling crowds with their tight formation dives and loops. Their airshow performances have been marred just three times by fatal accidents since the formation of the squadron in 1953. But the worst accident they suffered was not during an airshow. It was during a routine flight over Idaho.

Just at sundown on October 9, 1958, several witnesses saw a cargo plane fly toward the sunset and into the silhouettes of a large flock of geese. The geese scattered, honking their disapproval. The plane’s engines stuttered, raced, then fell silent. The pilot had time to lower the landing gear and was probably looking for a place to put the aircraft down. Instead, it plowed nose first into a brush-covered hillside about six miles southeast of Payette, a ball of flame marking its impact.

The twin-engined Fairchild C123 was on its way from Hill AFB in Utah to McChord AFB in Washington. On board was a flight crew of five along with 14 aircraft maintenance personnel assigned to the Thunderbird squadron. None of the 19 survived. It remains the worst accident ever suffered by the Thunderbird team.

One year after the crash, members of the Payette High School Key Club dedicated a triangle-shaped monument to those who died. It is located in a small park and rest area on State Highway 52 south of Payette. The community has honored the crash victims with an annual ceremony ever since. This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

The Thunderbirds are a demonstration squadron based at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. They perform aerial acrobatics all over the country, thrilling crowds with their tight formation dives and loops. Their airshow performances have been marred just three times by fatal accidents since the formation of the squadron in 1953. But the worst accident they suffered was not during an airshow. It was during a routine flight over Idaho.

Just at sundown on October 9, 1958, several witnesses saw a cargo plane fly toward the sunset and into the silhouettes of a large flock of geese. The geese scattered, honking their disapproval. The plane’s engines stuttered, raced, then fell silent. The pilot had time to lower the landing gear and was probably looking for a place to put the aircraft down. Instead, it plowed nose first into a brush-covered hillside about six miles southeast of Payette, a ball of flame marking its impact.

The twin-engined Fairchild C123 was on its way from Hill AFB in Utah to McChord AFB in Washington. On board was a flight crew of five along with 14 aircraft maintenance personnel assigned to the Thunderbird squadron. None of the 19 survived. It remains the worst accident ever suffered by the Thunderbird team.

One year after the crash, members of the Payette High School Key Club dedicated a triangle-shaped monument to those who died. It is located in a small park and rest area on State Highway 52 south of Payette. The community has honored the crash victims with an annual ceremony ever since.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

This is a Fairchild C123 much like the one that crashed near Payette in 1958.

Published on November 04, 2021 04:00

November 3, 2021

Escape! Part Two (Tap to read the story)

We told you about Prisoner Number 2 in Idaho’s Territorial Prison and his first escape attempt yesterday. We’ll continue that story today.

As noted, Moroni Hicks’ status as Prisoner Number 2 doesn’t mean a lot. They didn’t start assigning numbers to prisoners until 1880, 16 years after the first territorial prison opened for business.

After his first escape and recapture a few weeks later, Hicks resigned himself to his fate as a prisoner. For a while.

Then, on a cold day in March 1883, Hicks and three other inmates, who were breaking rocks at the quarry above the prison at Table Rock, rushed their guards and escaped. Besides Hicks there was Charles Chambers, a stage robber; J.W Hayes, serving time for larceny; and Ralph Johnson, a burglar from Wood River. They hightailed it into the hills with captured rifles.

Boise City Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins must have been especially aggravated at the escape. Just three years earlier, as a deputy U.S. Marshal, Robbins had chased down Moroni Hicks and some different prisoners who had escaped while picking apples at an orchard next to the prison.

The fugitives this time stopped in at the ranch of Mike McMahan, which was just over the hill from Table Rock, to requisition horses and food. The rancher was livid because they had relieved him of two of his best mounts.

Territorial Governor John Neil put a hundred-dollar reward on the heads of the men. This was a downgrade for Hicks, who at the peak of the hunt for him in the 1880 escape, he was worth $1,000 to anyone who brought him back, breathing or not.

Early on there was a shootout, probably, between the pursuing posse and Hicks and Hayes when they tried to cross the Boise River under cover of darkness. No one was hit, so some of that is speculation.

Meanwhile, Mike McMahan, the rancher, had set out following hoofprints into the Owyhee desert hoping to retrieve his horses. Ten days after he had been robbed, McMahan caught up with escapee Ralph Johnson and a couple of purloined horses on Catherine Creek, which is between Oreana and Grandview. Johnson gave up without a fight and McMahan got his horses back.

In mid-April, Moroni Hicks turned up in Canyon City, Oregon, where he had been arrested in a barroom brawl.

Rube Robbins eventually chased down Charles Chambers in an Oregon Asylum where he was living under an assumed name and pretending to have lost his wits.

J.W. Hayes seems to have vanished completely.

The common thread in these two escapes, Prisoner Number 2, aka Moroni Hicks, was released from prison in August 1891, after serving for eleven years. He married Lucinda Owen in June 1893 in Kane, Utah. They had eight children together. Moroni passed away on March 17, 1931 and is buried in the Oddfellows Cemetery in Los Angeles.

As noted, Moroni Hicks’ status as Prisoner Number 2 doesn’t mean a lot. They didn’t start assigning numbers to prisoners until 1880, 16 years after the first territorial prison opened for business.

After his first escape and recapture a few weeks later, Hicks resigned himself to his fate as a prisoner. For a while.

Then, on a cold day in March 1883, Hicks and three other inmates, who were breaking rocks at the quarry above the prison at Table Rock, rushed their guards and escaped. Besides Hicks there was Charles Chambers, a stage robber; J.W Hayes, serving time for larceny; and Ralph Johnson, a burglar from Wood River. They hightailed it into the hills with captured rifles.

Boise City Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins must have been especially aggravated at the escape. Just three years earlier, as a deputy U.S. Marshal, Robbins had chased down Moroni Hicks and some different prisoners who had escaped while picking apples at an orchard next to the prison.

The fugitives this time stopped in at the ranch of Mike McMahan, which was just over the hill from Table Rock, to requisition horses and food. The rancher was livid because they had relieved him of two of his best mounts.

Territorial Governor John Neil put a hundred-dollar reward on the heads of the men. This was a downgrade for Hicks, who at the peak of the hunt for him in the 1880 escape, he was worth $1,000 to anyone who brought him back, breathing or not.

Early on there was a shootout, probably, between the pursuing posse and Hicks and Hayes when they tried to cross the Boise River under cover of darkness. No one was hit, so some of that is speculation.

Meanwhile, Mike McMahan, the rancher, had set out following hoofprints into the Owyhee desert hoping to retrieve his horses. Ten days after he had been robbed, McMahan caught up with escapee Ralph Johnson and a couple of purloined horses on Catherine Creek, which is between Oreana and Grandview. Johnson gave up without a fight and McMahan got his horses back.

In mid-April, Moroni Hicks turned up in Canyon City, Oregon, where he had been arrested in a barroom brawl.

Rube Robbins eventually chased down Charles Chambers in an Oregon Asylum where he was living under an assumed name and pretending to have lost his wits.

J.W. Hayes seems to have vanished completely.

The common thread in these two escapes, Prisoner Number 2, aka Moroni Hicks, was released from prison in August 1891, after serving for eleven years. He married Lucinda Owen in June 1893 in Kane, Utah. They had eight children together. Moroni passed away on March 17, 1931 and is buried in the Oddfellows Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Published on November 03, 2021 04:00

November 2, 2021

Escape! Part One (Tap to read the story)

When you’re Prisoner Number 2 in the Idaho system, maybe you just try harder. Could that explain Moroni Hicks’ persistence in escaping?

Hicks’ low number—coveted by criminals everywhere—is a little misleading. He was an early prisoner, but many others weren’t assigned a number in the first years of the prison. The Idaho Territorial Prison had been accepting guests since 1864. Hicks checked in in 1880, convicted of second-degree murder.

Moroni Hicks was the third of eight children born to George Armstrong and Elizabeth Temperance Jolley Hicks in Spanish Fork, Utah in 1859. We know little about the murder for which they convicted him, except that the victim was a man named Johnson in Sandhole, which was an early name for Hamer.

Booking photos for Hicks got lost when his prison file was being examined by the attorney general’s office to determine his eligibility for parole. One poor photo of him from later years exists (below). We know he was a large man, but his description varied depending on who was telling the story. When they booked him into the territorial prison, they described Hicks as six feet three and one-fourth inches with a light complexion, grey eyes, and light brown hair. In a later account, he was six-six with red whiskers.

Hicks made his first escape on September 3, 1880, not long after his incarceration. He and five other convicts were picking apples in the Robert Wilson orchard when they rushed their guard and the orchard owner, overpowering them. Five of the prisoners chopped off their shackles, stole some guns, including two shotguns, and a cartridge belt.

The orchard was near the prison. C.W. Newman, a prison guard, heard Mrs. Wilson screaming. He mounted his horse and rode over to investigate. When he got near the house, one of the convicts shot him in the face. As he fell and turned, someone shot him in the back.

Other prison guards had dashed into town to tell of the escape. In minutes a posse formed, including several soldiers from Fort Boise. When the posse arrived at the orchard, they met a fusillade from the house where the Wilsons were now held hostage.

A cavalry corporal took a bullet to his body. Another soldier gave covering fire for his downed comrade and hit convict William Reese. He would die the next day and the corporal would recover. One of the convicts who had failed to cut his chains off and gave up.

That left four men desperate to escape. They were Moroni Hicks and John Wilson, both doing time for manslaughter, and William Mays and W.H. Overholt (or Overholtz) who were in for life for mail robbery.

Somehow, the four convicts slipped away through the orchard to the Boise River. They swam across and found some horses to steal. Wilson took off on his own for Oregon, while the other three headed east.

The next day word of the escapees came back to Boise from travelers on the Overland road. The men had held up six hunters and ranchers at a ranch 40 miles northeast of Boise. That netted them new horses, some mules, blankets, boots, and other provisions. Convict Mays became especially enamored with a new hat he was able to steal. As far as he knew his old one was back in the Boise orchard with a bullet hole through the crown.

The escapees terrorized several people along their route. Meanwhile, U.S. Marshall E.S. Chase was offering a reward for their capture, $1,000, dead or alive.

On their way east the escaped prisoners raided the Glenn home in Glenn’s Ferry, walking off with canned oysters and salmon.

Further east they were spotted by J.W. White at the mouth of Malad Gorge. A brief shootout with White had no apparent effect on anyone. White wrote to Deputy U.S. Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins, head of the pursuing posse, that “I am inclined to think we shall have to kill Mays and Overholtz.” He thought Prisoner Number Two, Moroni Hicks, was more interested in escape than a gun fight.

Hard up for food, the escapees had killed an ox a few days before, a piece of which White had seen, describing the meat as “black as my hat.”

What followed was a hunt through the rocky bottom of Malad Gorge, with occasional gunfire. The fugitives had claimed a cave for their own protection. The posse was sure they had them surrounded and that it would all be over at daybreak. Dawn came and what they found was the escapees had sneaked out during the night.

A night or two later their hunger proved to be the fugitives’ undoing. Marshals spotted a guttering little fire inside a ranch corral not far from the gorge. Cold and hungry the men had dug up some potatoes which they were attempting to roast.

Captured with no further resistance, the men were returned to Boise to face new charges. But this would not be the last taste of freedom for Moroni Hicks.

The story concludes tomorrow.

Hicks’ low number—coveted by criminals everywhere—is a little misleading. He was an early prisoner, but many others weren’t assigned a number in the first years of the prison. The Idaho Territorial Prison had been accepting guests since 1864. Hicks checked in in 1880, convicted of second-degree murder.

Moroni Hicks was the third of eight children born to George Armstrong and Elizabeth Temperance Jolley Hicks in Spanish Fork, Utah in 1859. We know little about the murder for which they convicted him, except that the victim was a man named Johnson in Sandhole, which was an early name for Hamer.

Booking photos for Hicks got lost when his prison file was being examined by the attorney general’s office to determine his eligibility for parole. One poor photo of him from later years exists (below). We know he was a large man, but his description varied depending on who was telling the story. When they booked him into the territorial prison, they described Hicks as six feet three and one-fourth inches with a light complexion, grey eyes, and light brown hair. In a later account, he was six-six with red whiskers.

Hicks made his first escape on September 3, 1880, not long after his incarceration. He and five other convicts were picking apples in the Robert Wilson orchard when they rushed their guard and the orchard owner, overpowering them. Five of the prisoners chopped off their shackles, stole some guns, including two shotguns, and a cartridge belt.

The orchard was near the prison. C.W. Newman, a prison guard, heard Mrs. Wilson screaming. He mounted his horse and rode over to investigate. When he got near the house, one of the convicts shot him in the face. As he fell and turned, someone shot him in the back.

Other prison guards had dashed into town to tell of the escape. In minutes a posse formed, including several soldiers from Fort Boise. When the posse arrived at the orchard, they met a fusillade from the house where the Wilsons were now held hostage.

A cavalry corporal took a bullet to his body. Another soldier gave covering fire for his downed comrade and hit convict William Reese. He would die the next day and the corporal would recover. One of the convicts who had failed to cut his chains off and gave up.

That left four men desperate to escape. They were Moroni Hicks and John Wilson, both doing time for manslaughter, and William Mays and W.H. Overholt (or Overholtz) who were in for life for mail robbery.

Somehow, the four convicts slipped away through the orchard to the Boise River. They swam across and found some horses to steal. Wilson took off on his own for Oregon, while the other three headed east.

The next day word of the escapees came back to Boise from travelers on the Overland road. The men had held up six hunters and ranchers at a ranch 40 miles northeast of Boise. That netted them new horses, some mules, blankets, boots, and other provisions. Convict Mays became especially enamored with a new hat he was able to steal. As far as he knew his old one was back in the Boise orchard with a bullet hole through the crown.

The escapees terrorized several people along their route. Meanwhile, U.S. Marshall E.S. Chase was offering a reward for their capture, $1,000, dead or alive.

On their way east the escaped prisoners raided the Glenn home in Glenn’s Ferry, walking off with canned oysters and salmon.

Further east they were spotted by J.W. White at the mouth of Malad Gorge. A brief shootout with White had no apparent effect on anyone. White wrote to Deputy U.S. Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins, head of the pursuing posse, that “I am inclined to think we shall have to kill Mays and Overholtz.” He thought Prisoner Number Two, Moroni Hicks, was more interested in escape than a gun fight.

Hard up for food, the escapees had killed an ox a few days before, a piece of which White had seen, describing the meat as “black as my hat.”

What followed was a hunt through the rocky bottom of Malad Gorge, with occasional gunfire. The fugitives had claimed a cave for their own protection. The posse was sure they had them surrounded and that it would all be over at daybreak. Dawn came and what they found was the escapees had sneaked out during the night.

A night or two later their hunger proved to be the fugitives’ undoing. Marshals spotted a guttering little fire inside a ranch corral not far from the gorge. Cold and hungry the men had dug up some potatoes which they were attempting to roast.

Captured with no further resistance, the men were returned to Boise to face new charges. But this would not be the last taste of freedom for Moroni Hicks.

The story concludes tomorrow.

Published on November 02, 2021 04:00

November 1, 2021

Coxey's Army Invades Boise (Tap to read)

Two Hundred Coxeyites Sentenced in Boise, Idaho, read the headline in The Christian Recorder Magazine's June 7, 1894 edition.

That caught my attention while searching for random subjects to feed to this blog. First, when you sentence 200 people for anything, there must be a story behind it. Second, what the heck were Coxeyites?

So, here's what I learned about Coxeyites and why so many of them were sentenced in Boise back in 1894.

The official name of those commonly known as Coxeyites or Coxey's Army was the Army of the Commonwealth in Christ. They were unemployed workers who organized for what was the first significant protest march on Washington, DC.

In 1894 there were plenty of unemployed people. The country was in the middle of the worst economic depression to date. Those out of work began to get behind Jacob Sechler Coxey, Sr. He had a big idea about infrastructure in the nation. A Socialist Party member, Coxey wanted to issue $500 million in paper money backed by government bonds. That money would land in the pockets of workers building roads nationwide. The idea would be echoed in the New Deal programs of the Great Depression a few decades later.

To say that he had some support is akin to saying there are a few stars in the sky. Tens of thousands of jobless men began to make their way toward Washington, where their voices might be heard.

There were a few problems associated with the march. First, these were men without money. How would they get to DC? Once they got there, where would they stay? What would they eat?

A large number of Coxeyites came from the Pacific Northwest. Many of them had formerly been railroad workers who blamed their problems on the railroads. So the army of workers hopped freights headed east.

As they traveled across the country, members of Coxey's Army were cheered along and often given food by local supporters. Railroads were less eager to help.

Coxeyites, frustrated by that lack of eagerness, began commandeering trains to take them east. In reaction, the railroads began throwing every obstacle they could in the way of men. They parked dead train engines on the tracks in Montana and Kansas, emptied water tanks—essential for steam engines—and even tore up tracks. The Coxeyites often just laid new track around the obstacles. To refill the purloined engines, they would stop at wells and use buckets and cups to dump water into the tanks.

Troops were called up in some states to stop the Coxeyites. But, more than once, the unemployed men turned the tables on those who would keep them from their destination, capturing the firearms meant to capture the Coxeyites.

At Huntington, Oregon, just a few miles from the Idaho border, about 250 Coxeyites demanded that the Union Pacific Railroad give them a ride east. UP resisted at first, fearing that caving in would set a precedent that would result in hundreds more Coxeyites demanding free passage up and down the West Coast.

Ultimately, the company relented and agreed to let the Coxeyites ride across Idaho "under protest."

This was a victory for the men and was cheered by many locals across Southern Idaho. In Pocatello, when about 300 Coxeyites pulled into town, sympathizers raised money for food and assisted them in many ways.

Meanwhile, Union Pacific officials decided letting the men ride for free was a mistake. As feared, they began getting demands from other members of Coxey's Army for a free ride. It was time to put a stop to it.

At the railroad's request, U.S. Marshall for Idaho, Joseph Pinkham, sent men to the border with Oregon to keep more men from coming into the state and headed a cadre of marshals and volunteers that went to Montpelier to keep the Coxeyites from entering Wyoming.

Coxey's Army had other ideas. They spent a day and most of a night arguing with the citizens of Montpelier, then with Marshall Pinkham, in what one newspaper reporter called "the most exciting day in the history of southeastern Idaho." Pinkham arrested a local man who was encouraging the Coxeyites to ignore a federal order to stand down. The crowd of the unemployed demanded his release, but Pinkham did not acquiesce. The tense standoff broke when Pinkham's train retreated from Montpellier with the arrestee.

A short time after the Pinkham train left, several of the men broke into the roundhouse and stole a locomotive. That engine jumped the tracks at a switch, disabling it. The men stole two more engines in Montpelier and charged into Wyoming at 6:22 in the morning.

That Montpelier triumph was short-lived for the Coxeyites. The train-nappers were overpowered in Green River and arrested.

The men found themselves back on a train, the occupants of guarded cattle cars on their way west, not east. About 200 were delivered to Boise for trial related to the stolen locomotive caper in mid-May 1894.

Housing 200 prisoners would prove a challenge. At first, they were to be housed at the prison. When authorities determined there wasn't room there, they decided to quarter them in the old post office. Again, not enough space.

When the Coxyites pulled into town, the boxcars they rode in rolled into the roundhouse and stopped. And, that's where they were housed, in and out of the boxcars and within the roundhouse, to begin with, guarded by two companies of troops and a posse of deputies.

The roundhouse and surrounding grounds, where the newspaper reported the prisoners "frolicked around on the grass like boys out for a holiday," quickly became known as Camp Pinkham. For his part, Pinkham looked out for his prisoners' interests. He ordered a 28-foot by 100-foot building erected for them to sleep in while waiting for Judge Beatty to come back from a trip to North Idaho.

On the judge's return in late May, the trial began. Justice was swift. On June 5, the judge handed out the sentences. Those who led the Coxeyites in stealing the train in Montpelier got the worst of it, each sentenced to six months in jail. The remainder of the men got sentences of 30 to 60 days. They would be housed in a temporary prison near Huntington, Oregon.

So, the Coxeyites who chose the path through southern Idaho on their aborted journey to Washington, DC, spent their summer in a crude enclosure along the bank of the Snake River instead.

Several delegations of Coxey's Army did make it to Washington, DC over that summer. Their protests changed little, but it marked the beginning of many marches on Washington for various causes that continue to this day.

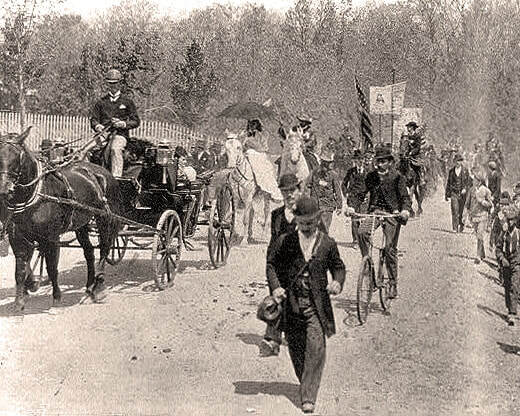

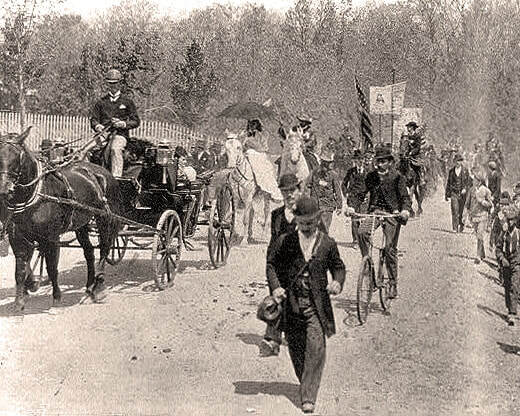

Coxeyites on the march, date and location unknown.

Coxeyites on the march, date and location unknown.

That caught my attention while searching for random subjects to feed to this blog. First, when you sentence 200 people for anything, there must be a story behind it. Second, what the heck were Coxeyites?

So, here's what I learned about Coxeyites and why so many of them were sentenced in Boise back in 1894.

The official name of those commonly known as Coxeyites or Coxey's Army was the Army of the Commonwealth in Christ. They were unemployed workers who organized for what was the first significant protest march on Washington, DC.

In 1894 there were plenty of unemployed people. The country was in the middle of the worst economic depression to date. Those out of work began to get behind Jacob Sechler Coxey, Sr. He had a big idea about infrastructure in the nation. A Socialist Party member, Coxey wanted to issue $500 million in paper money backed by government bonds. That money would land in the pockets of workers building roads nationwide. The idea would be echoed in the New Deal programs of the Great Depression a few decades later.

To say that he had some support is akin to saying there are a few stars in the sky. Tens of thousands of jobless men began to make their way toward Washington, where their voices might be heard.

There were a few problems associated with the march. First, these were men without money. How would they get to DC? Once they got there, where would they stay? What would they eat?

A large number of Coxeyites came from the Pacific Northwest. Many of them had formerly been railroad workers who blamed their problems on the railroads. So the army of workers hopped freights headed east.

As they traveled across the country, members of Coxey's Army were cheered along and often given food by local supporters. Railroads were less eager to help.

Coxeyites, frustrated by that lack of eagerness, began commandeering trains to take them east. In reaction, the railroads began throwing every obstacle they could in the way of men. They parked dead train engines on the tracks in Montana and Kansas, emptied water tanks—essential for steam engines—and even tore up tracks. The Coxeyites often just laid new track around the obstacles. To refill the purloined engines, they would stop at wells and use buckets and cups to dump water into the tanks.

Troops were called up in some states to stop the Coxeyites. But, more than once, the unemployed men turned the tables on those who would keep them from their destination, capturing the firearms meant to capture the Coxeyites.

At Huntington, Oregon, just a few miles from the Idaho border, about 250 Coxeyites demanded that the Union Pacific Railroad give them a ride east. UP resisted at first, fearing that caving in would set a precedent that would result in hundreds more Coxeyites demanding free passage up and down the West Coast.

Ultimately, the company relented and agreed to let the Coxeyites ride across Idaho "under protest."

This was a victory for the men and was cheered by many locals across Southern Idaho. In Pocatello, when about 300 Coxeyites pulled into town, sympathizers raised money for food and assisted them in many ways.

Meanwhile, Union Pacific officials decided letting the men ride for free was a mistake. As feared, they began getting demands from other members of Coxey's Army for a free ride. It was time to put a stop to it.

At the railroad's request, U.S. Marshall for Idaho, Joseph Pinkham, sent men to the border with Oregon to keep more men from coming into the state and headed a cadre of marshals and volunteers that went to Montpelier to keep the Coxeyites from entering Wyoming.

Coxey's Army had other ideas. They spent a day and most of a night arguing with the citizens of Montpelier, then with Marshall Pinkham, in what one newspaper reporter called "the most exciting day in the history of southeastern Idaho." Pinkham arrested a local man who was encouraging the Coxeyites to ignore a federal order to stand down. The crowd of the unemployed demanded his release, but Pinkham did not acquiesce. The tense standoff broke when Pinkham's train retreated from Montpellier with the arrestee.

A short time after the Pinkham train left, several of the men broke into the roundhouse and stole a locomotive. That engine jumped the tracks at a switch, disabling it. The men stole two more engines in Montpelier and charged into Wyoming at 6:22 in the morning.

That Montpelier triumph was short-lived for the Coxeyites. The train-nappers were overpowered in Green River and arrested.

The men found themselves back on a train, the occupants of guarded cattle cars on their way west, not east. About 200 were delivered to Boise for trial related to the stolen locomotive caper in mid-May 1894.

Housing 200 prisoners would prove a challenge. At first, they were to be housed at the prison. When authorities determined there wasn't room there, they decided to quarter them in the old post office. Again, not enough space.

When the Coxyites pulled into town, the boxcars they rode in rolled into the roundhouse and stopped. And, that's where they were housed, in and out of the boxcars and within the roundhouse, to begin with, guarded by two companies of troops and a posse of deputies.

The roundhouse and surrounding grounds, where the newspaper reported the prisoners "frolicked around on the grass like boys out for a holiday," quickly became known as Camp Pinkham. For his part, Pinkham looked out for his prisoners' interests. He ordered a 28-foot by 100-foot building erected for them to sleep in while waiting for Judge Beatty to come back from a trip to North Idaho.

On the judge's return in late May, the trial began. Justice was swift. On June 5, the judge handed out the sentences. Those who led the Coxeyites in stealing the train in Montpelier got the worst of it, each sentenced to six months in jail. The remainder of the men got sentences of 30 to 60 days. They would be housed in a temporary prison near Huntington, Oregon.

So, the Coxeyites who chose the path through southern Idaho on their aborted journey to Washington, DC, spent their summer in a crude enclosure along the bank of the Snake River instead.

Several delegations of Coxey's Army did make it to Washington, DC over that summer. Their protests changed little, but it marked the beginning of many marches on Washington for various causes that continue to this day.

Coxeyites on the march, date and location unknown.

Coxeyites on the march, date and location unknown.

Published on November 01, 2021 04:00

October 31, 2021

Pop Quiz! (Tap to Read)

Below is a little Idaho trivia quiz. If you’ve been following Speaking of Idaho, you might do very well. Caution, it is my job to throw you off the scent. Answers below the picture. If you missed that story, click the letter for a link.

1). How did C.E. Bell die in 1907?

A. He fell into a frozen lake.

B. He fell into an ice fissure.

C. He fell from a horse.

D. He fell into a volcano.

E. He fell in with a bad crowd.

2). What Idaho author wrote the screenplay for Strangers on a Train?

A. Vardis Fisher

B. Agnes Just Reid

C. Czenzi Ormonde

D. Dick D’Easum

E. Wilson Rawls

3). What office did Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson’s brother hold?

A. Idaho Secretary of State

B. Nevada Governor

C. Nevada Secretary of State

D. Idaho Governor

E. Utah Governor

4). Where was I met Him in Paris filmed?

A. Paris, of course.

B. Boise.

C. Preston.

D. Sun Valley.

E. Coeur d’Alene.

5) What kind of Idaho mine made Benjamin Franklin White a fortune?

A. Gold.

B. Coal.

C. Silver

D. Salt

E. Gravel Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

1, D

2, C

3, B

4, D

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

1). How did C.E. Bell die in 1907?

A. He fell into a frozen lake.

B. He fell into an ice fissure.

C. He fell from a horse.

D. He fell into a volcano.

E. He fell in with a bad crowd.

2). What Idaho author wrote the screenplay for Strangers on a Train?

A. Vardis Fisher

B. Agnes Just Reid

C. Czenzi Ormonde

D. Dick D’Easum

E. Wilson Rawls

3). What office did Territorial Governor Edward A. Stevenson’s brother hold?

A. Idaho Secretary of State

B. Nevada Governor

C. Nevada Secretary of State

D. Idaho Governor

E. Utah Governor

4). Where was I met Him in Paris filmed?

A. Paris, of course.

B. Boise.

C. Preston.

D. Sun Valley.

E. Coeur d’Alene.

5) What kind of Idaho mine made Benjamin Franklin White a fortune?

A. Gold.

B. Coal.

C. Silver

D. Salt

E. Gravel

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)

Answers (If you missed that story, click the letter for a link)1, D

2, C

3, B

4, D

5, D

How did you do?

5 right—Why aren’t you writing this blog?

4 right—A true Idaho native, no matter where you’re from.

3 right—Good! Treat yourself to some French fries.

2 right—Okay! Eat more potatoes!

1 right—Meh. You need to read more blog posts.

0 right—Really, you should reconsider your recent relocation.

Published on October 31, 2021 04:00

October 30, 2021

Halloween Pranks (Tap to Read)

Halloween has been celebrated in the United States since the late 18th or early 19th century. In early Idaho newspapers it was mentioned mostly as a time when young hooligans used the night as an excuse to perform mostly minor mischief.

Removing signs and placing objects in the way on sidewalks and streets was popular in the early part of the 20th century. Horses roamed from where they were tied to points far away. When automobiles became the preferred mode of transportation, they had a tendency to disappear from their parking spots only to reappear across town.

In 1910, the Idaho Republican reported that “Half a dozen of the home boys were caught putting things into the sewer while playing Halloween pranks and were taken into custody.”

Many papers editorialized against the semi-sanctioned mischief. In 1915, the Blackfoot Optimist opined that “There is no questioning the fact that in recent years the spirit of Hallowe’en has become so lost sight of; Hallowe’en celebrations have become so perverted by many youngsters that instead of it being romantic, delightful and pleasing to all, Hallowe’en has become a time of terror to householders and a period of ribald license to many youngsters.

“It is a good idea to teach boys and girls that soaping windows, defacing property and committing acts of malicious mischief are not more to be sanctioned on Hallowe’en and during the weeks preceding that occasion than at any other time of year.”

The Mountain Home Republican covered the tipping over of small buildings—likely outhouses—and the soaping of windows in 1917. Damage for the night was estimated at $150. The paper noted that some residents vowed that “next year they will guard their property with shot guns.”

In 1918, The Idaho Republican in Blackfoot reported that someone had placed a “small building” on top of a drug store in Murtaugh, nearly destroying the roof of the business. Calling outhouses “small buildings” was apparently a nod to decorum.

All of these minor pranks pre-dated trick or treating. Dressing up like your favorite celebrity or throwing a sheet over your head with eyeholes cut in it to go door-to-door begging for candy didn’t become a widespread tradition until the 1930s. The first reference to the practice to appear in the Idaho Statesman was in 1938 in an ad for trick or treat candy, which was on sale for ten cents a pound at CC Anderson’s Golden Rule Store.

Removing signs and placing objects in the way on sidewalks and streets was popular in the early part of the 20th century. Horses roamed from where they were tied to points far away. When automobiles became the preferred mode of transportation, they had a tendency to disappear from their parking spots only to reappear across town.

In 1910, the Idaho Republican reported that “Half a dozen of the home boys were caught putting things into the sewer while playing Halloween pranks and were taken into custody.”

Many papers editorialized against the semi-sanctioned mischief. In 1915, the Blackfoot Optimist opined that “There is no questioning the fact that in recent years the spirit of Hallowe’en has become so lost sight of; Hallowe’en celebrations have become so perverted by many youngsters that instead of it being romantic, delightful and pleasing to all, Hallowe’en has become a time of terror to householders and a period of ribald license to many youngsters.

“It is a good idea to teach boys and girls that soaping windows, defacing property and committing acts of malicious mischief are not more to be sanctioned on Hallowe’en and during the weeks preceding that occasion than at any other time of year.”

The Mountain Home Republican covered the tipping over of small buildings—likely outhouses—and the soaping of windows in 1917. Damage for the night was estimated at $150. The paper noted that some residents vowed that “next year they will guard their property with shot guns.”

In 1918, The Idaho Republican in Blackfoot reported that someone had placed a “small building” on top of a drug store in Murtaugh, nearly destroying the roof of the business. Calling outhouses “small buildings” was apparently a nod to decorum.

All of these minor pranks pre-dated trick or treating. Dressing up like your favorite celebrity or throwing a sheet over your head with eyeholes cut in it to go door-to-door begging for candy didn’t become a widespread tradition until the 1930s. The first reference to the practice to appear in the Idaho Statesman was in 1938 in an ad for trick or treat candy, which was on sale for ten cents a pound at CC Anderson’s Golden Rule Store.

Published on October 30, 2021 04:00

October 29, 2021

KID TV Goes on the Air (Tap to Read)

Since I hit my 50th birthday, looong ago, I’ve recognized that by most standards I qualify as an antique. Even so, it is a little shocking to be writing about this historical event that was one of my earliest memories.

KID television in Idaho Falls came on the air with programming on Sunday, December 20, 1953. Since I was four it’s remarkable that I remember anything at all about the first television broadcast in southeastern Idaho. But, how could one forget the flamboyant Liberace?

We were watching at my aunt and uncle’s house in Idaho Falls. Pop hadn’t yet sprung for a TV set, though it wouldn’t be long before we had one. I remember the camera panning over the audience and Pop making a comment about some bald guy having less hair than he did.

One of the first mentions of the new TV station came on April 29, 1953, when CBS announced that KID would become its 111th affiliate. The release said they expected to start broadcasting on June 14. Technical issues kept pushing that date out.

With the 100,000 watt transmitter for KID located on one of the Twin Buttes, they expected to get their signal into Twin Falls and the rest of the Magic Valley. Technically, they did, but it was never a signal to brag about.

That didn’t stop stores from stocking televisions in Twin Falls. The Times-News also ran frequent ads suggesting that television repair had a promising future and helpfully giving the address of a school in California.

In Pocatello, they formed the Pocatello Television Dealers Association in anticipation of the big day, listing the programming a week ahead of the first broadcast to entice buyers to come in and shop.

In Blackfoot, Peterson’s, “The store that serves you best,” sold my folks a 17” Philco that seemed like a miracle to me. I watched whatever was on, at first, eventually growing more selective. My favorite was “Disneyland,” which started with Tinkerbell tapping her magic wand to set off sparkles and the opening of stage curtains. After the requisite sponsor blurbs, “When You Wish Upon a Star,” began playing. Other favorites came along, such as “The Cisco Kid,” “Maverick,” and “Sky King.”

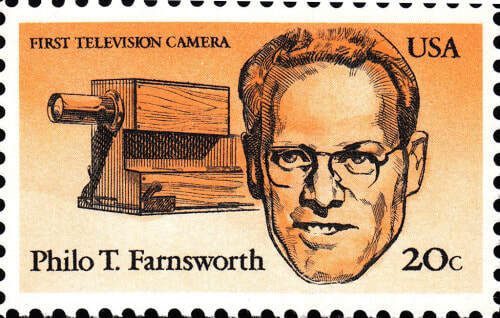

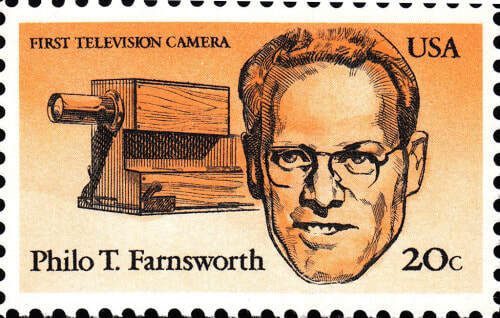

KID’s first programming came a dozen years after the first commercial broadcast. That was in 1941 in New York City. But the eastern Idaho event had something earlier broadcasts did not. They had the inventor of television as a guest. Philo T. Farnsworth, who as a freshman at Rigby High School had come up with the concept for the cathode ray tube, helped KID TV celebrate its first broadcast.

A KID TV program guide from 1958, four years after the station aired the first television broadcast in eastern Idaho.

A KID TV program guide from 1958, four years after the station aired the first television broadcast in eastern Idaho.  When KID TV first went on the air in 1954 the inventor of television was there to help them celebrate. Philo T. Farnsworth had come up with the idea for the cathode ray tube as a freshman at Rigby High School.

When KID TV first went on the air in 1954 the inventor of television was there to help them celebrate. Philo T. Farnsworth had come up with the idea for the cathode ray tube as a freshman at Rigby High School.

KID television in Idaho Falls came on the air with programming on Sunday, December 20, 1953. Since I was four it’s remarkable that I remember anything at all about the first television broadcast in southeastern Idaho. But, how could one forget the flamboyant Liberace?

We were watching at my aunt and uncle’s house in Idaho Falls. Pop hadn’t yet sprung for a TV set, though it wouldn’t be long before we had one. I remember the camera panning over the audience and Pop making a comment about some bald guy having less hair than he did.

One of the first mentions of the new TV station came on April 29, 1953, when CBS announced that KID would become its 111th affiliate. The release said they expected to start broadcasting on June 14. Technical issues kept pushing that date out.

With the 100,000 watt transmitter for KID located on one of the Twin Buttes, they expected to get their signal into Twin Falls and the rest of the Magic Valley. Technically, they did, but it was never a signal to brag about.

That didn’t stop stores from stocking televisions in Twin Falls. The Times-News also ran frequent ads suggesting that television repair had a promising future and helpfully giving the address of a school in California.