Rick Just's Blog, page 114

September 16, 2021

The Missing Silver Set

In January 1975 thieves broke into the Utah State Historical Society and stole $22,380 worth of silver which had once been part of the officers’ mess on the USS Utah. The thieves entered the building via scaffolding that was in use for repairs. The collection included cups, plates, and trays made of sterling silver from the Utah and a sword from an unrelated collection.

And, it is about now that you’re wondering what this has to do with Idaho. Nothing. Maybe.

Just over a year later, the headline in The Idaho Statesman read, “Burglars Loot Museum, Steal Silver.” This time the burglary was in Idaho and the loot was from the USS Idaho. The value of the purloined silver service in Idaho was set as “several hundred dollars,” but it wasn’t the monetary value the Idaho State Historical Society was worried about. The silver tea service from the Idaho, along with a few silver ingots and medals given to Governor Cecil D. Andrus at the Western Governor’s Conference the year before, were prized for their historical value.

The sterling silver tea service had been used during inaugural balls ever since the Idaho had been decommissioned in 1946. It was irreplaceable.

In the Idaho burglary there was no handy scaffolding for the thieves to climb. They brought a ladder with them. One of the burglars—perhaps it was a single burglar—climbed up to reach a window on an enclosed porch, broke the window, then crawled in. This may have been a clue. The window was one foot by one-and-a-half feet, meaning the culprit must have been small.

Once inside the thief or thieves smashed the display case glass to get to the tea set. Police speculated that they used the punch bowl from the set as a basket, piling the rest of the loot inside. They went out a door and fled northeast across Julia Davis Park, marking their route when they dropped a serving tray from the set, not bothering to retrieve it.

And that, sadly, is the end of the story. None of the silver from either robbery was ever recovered. It was likely melted down and cashed in.

The tea service from the USS Idaho had a history with the WWII ship, but its connection to Idaho went even further back. The service was donated by the people of Idaho for use on the predecessor ship, the USS Idaho in 1912, so it had served on two ships bearing that name.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

And, it is about now that you’re wondering what this has to do with Idaho. Nothing. Maybe.

Just over a year later, the headline in The Idaho Statesman read, “Burglars Loot Museum, Steal Silver.” This time the burglary was in Idaho and the loot was from the USS Idaho. The value of the purloined silver service in Idaho was set as “several hundred dollars,” but it wasn’t the monetary value the Idaho State Historical Society was worried about. The silver tea service from the Idaho, along with a few silver ingots and medals given to Governor Cecil D. Andrus at the Western Governor’s Conference the year before, were prized for their historical value.

The sterling silver tea service had been used during inaugural balls ever since the Idaho had been decommissioned in 1946. It was irreplaceable.

In the Idaho burglary there was no handy scaffolding for the thieves to climb. They brought a ladder with them. One of the burglars—perhaps it was a single burglar—climbed up to reach a window on an enclosed porch, broke the window, then crawled in. This may have been a clue. The window was one foot by one-and-a-half feet, meaning the culprit must have been small.

Once inside the thief or thieves smashed the display case glass to get to the tea set. Police speculated that they used the punch bowl from the set as a basket, piling the rest of the loot inside. They went out a door and fled northeast across Julia Davis Park, marking their route when they dropped a serving tray from the set, not bothering to retrieve it.

And that, sadly, is the end of the story. None of the silver from either robbery was ever recovered. It was likely melted down and cashed in.

The tea service from the USS Idaho had a history with the WWII ship, but its connection to Idaho went even further back. The service was donated by the people of Idaho for use on the predecessor ship, the USS Idaho in 1912, so it had served on two ships bearing that name.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

The silver serving set from the USS Idaho, most of which was stolen in 1976. Photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society, 77-2-19.

Published on September 16, 2021 04:00

September 15, 2021

The Iconic Natatorium

Perhaps the first example of magnificent architecture in the Treasure Valley—before the valley had that name—was Boise’s Natatorium. Dedicated in 1892, the “Nat” cost $87,000 to build. Taxpayers in a town of 2500 would have been hard pressed to build a public pool of that grandeur. It was built as a money-making enterprise by the Boise Artesian Hot & Cold Water Company. Soon, houses along Warm Springs Avenue were advertising that they were heated with “Natatorium water.”

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

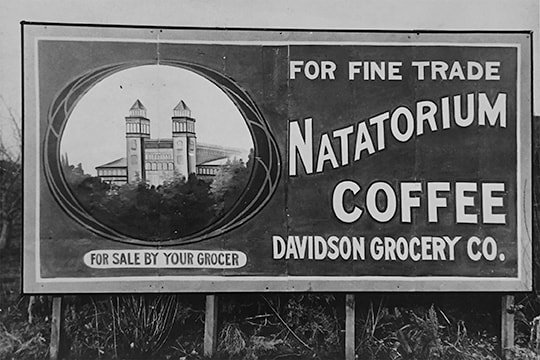

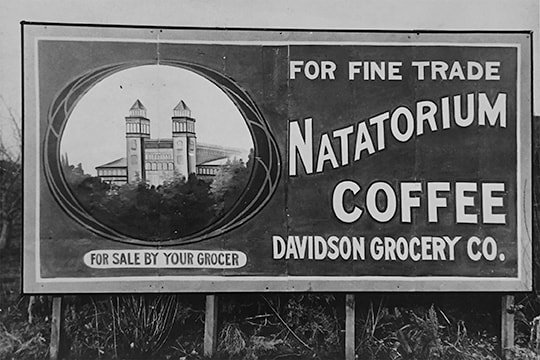

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)  Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The three-story entrance building, designed in the Moorish style, had twin towers soaring 112 feet into the air on the two front corners. Patrons passed a smoking room on the left and a ladies parlor on the right as they entered. There was a fine café on the top floor, billiard and card rooms, a saloon, tea rooms, a gym, and a balcony dance floor. But the water was the real attraction.

The pool was 125 by 60 feet rippling beneath a 40-foot arched roof. At the south end water cascaded over rocks creating an artificial grotto. There were diving boards for every level of daredevil from five feet to 60 feet. A waterslide extended into the pool from the first balcony and for the particularly courageous a trapeze hung down from the roof.

You would expect people to be dressed in their finery for dances and special events at the Nat, but they didn’t undress much to enter the pool in the early years. Men wore two-piece swimming suits consisting of a short-sleeve shirt and long shorts, while women dipped their toes wearing below-the-knees bloomers and knee-length skirts. Their blouses, which were considered a bit daring, featured puffed sleeves. Just to assure flashes of skin were kept to a minimum, the ladies also wore long stockings.

Travelers to Boise seldom missed a chance to see the Natatorium in the early days. It was the biggest swimming pool in the West. If visitors craved even more entertainment, they could chance the carnival rides at the adjacent White City Park, one of many across the country playing up on the nickname of Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. The park had a fun house, a roller coaster, a lagoon for paddle boats, a miniature train, and a hot air balloon launch pad.

The Nat was the site of countless weddings, fund-raisers and even inaugural balls during its reign on Warm Springs Avenue. The temperature of the springs that fed the Nat was 170 degrees coming out of the ground and had to be cooled to a pleasant 85 for the pool.

Hot water was what made the Nat possible, but it was also hot water that proved its demise. Much of the classic building was built from wood. Steam and humidity took their toll on the structure.

An ad for the Natatorium that ran on April 29, 1934, led with the line, “Swimming at the NATATORIM is one sport that is not affected by weather.” The irony of that came to light a few weeks later in July, when a freak windstorm brought one of the humidity-weakened roof beams crashing down into the pool, miraculously missing the swimmers.

The owners soon tore down the deteriorating building. There was talk of reconstructing it, but talk was all it was. The City of Boise eventually bought the property and opened a new outdoor pool on the site. There’s a functional support building there behind Adams Elementary. It’s unlikely it will ever generate quite the love that Boise had for the Nat during its 42-year history.

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)

Natatorium Coffee was available locally, featuring a picture of Boise’s Nat. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo 74-15251F)  Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Boise’s twin-tower Natatorium an example of Moorish architecture. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)  The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

The Nat’s main plunge featured a 60 by 125-foot pool. (Idaho State Historical Society Photo)

Published on September 15, 2021 04:00

September 14, 2021

Skating Around Boise

Belgian inventor John Joseph Merlin was a couple of centuries ahead of his time when he patented the first roller skate in 1760. His skates were just ice skates with rollers replacing the blade. He had basically invented the Rollerblade, not the roller skate. They weren’t popular because they were hard to steer and even harder to stop.

What we think of today as a roller skate came along in 1863, when James Plimpton of Massachusetts invented the familiar four-wheel design we know today. It was easier to turn because each wheel turned independently, allowing one to turn by putting one’s weight to one side of the skate. To say that they caught on would be an understatement. By 1871, even that outpost of civilization, Boise, had a skating rink.

Ads for the roller-skating rink at Templar Hall proclaimed that one could skate on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays during specified hours, with a “special assembly for the ladies” each of those days from 1 to 3 pm. After paying a quarter for admission you could pay another quarter to rent skates, if you didn’t have a pair of your own.

The rink pointed out that they had “the exclusive right for Plimpton’s Patent Roller Skates for Idaho Territory, same as used at the Pavilion Rink, San Francisco.”

In 1884 another rink opened in the city for “a multitude of excellent manipulators of the rollers” according to The Statesman. The rink was located in the newly converted opera house, and reportedly well managed. “In the evening the crowd was so large that the greatest precaution was necessary in order to preserve due regularity in the movements of skaters and Mr. P. F. Beal performed the duty of floor manager with commendable care and courtesy.”

A few mishaps were bound to occur. “The number of new beginners present was large and some falls were the result of too much haste and confidence.” Some were eager to take advantage of the newbies of a certain gender. “The young gentlemen who were masters of the rollers took the greatest imaginable delight in teaching young lady beginners the art and evidently the rink will be ‘all the rage’ this winter.”

But all was not perfection in the world of skating. A few weeks before statehood in 1890 The Statesman reported that “The walk to the Capitol from the corner of Seventh and Jefferson was taken possession of by boys with roller skates before it had become sufficiently hardened, and as a result it is very much creased and disfigured.” Cracks had also appeared in the concrete, perhaps likewise caused by unrestrained hooligan skaters. “Those cracks and creases will probably be an ‘eye-sore’ for years,” the paper concluded.

Today the wheels of skateboards are more often blamed for damage, real or imagined, but roller skates and enticing stretches of concrete are still with us.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

What we think of today as a roller skate came along in 1863, when James Plimpton of Massachusetts invented the familiar four-wheel design we know today. It was easier to turn because each wheel turned independently, allowing one to turn by putting one’s weight to one side of the skate. To say that they caught on would be an understatement. By 1871, even that outpost of civilization, Boise, had a skating rink.

Ads for the roller-skating rink at Templar Hall proclaimed that one could skate on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays during specified hours, with a “special assembly for the ladies” each of those days from 1 to 3 pm. After paying a quarter for admission you could pay another quarter to rent skates, if you didn’t have a pair of your own.

The rink pointed out that they had “the exclusive right for Plimpton’s Patent Roller Skates for Idaho Territory, same as used at the Pavilion Rink, San Francisco.”

In 1884 another rink opened in the city for “a multitude of excellent manipulators of the rollers” according to The Statesman. The rink was located in the newly converted opera house, and reportedly well managed. “In the evening the crowd was so large that the greatest precaution was necessary in order to preserve due regularity in the movements of skaters and Mr. P. F. Beal performed the duty of floor manager with commendable care and courtesy.”

A few mishaps were bound to occur. “The number of new beginners present was large and some falls were the result of too much haste and confidence.” Some were eager to take advantage of the newbies of a certain gender. “The young gentlemen who were masters of the rollers took the greatest imaginable delight in teaching young lady beginners the art and evidently the rink will be ‘all the rage’ this winter.”

But all was not perfection in the world of skating. A few weeks before statehood in 1890 The Statesman reported that “The walk to the Capitol from the corner of Seventh and Jefferson was taken possession of by boys with roller skates before it had become sufficiently hardened, and as a result it is very much creased and disfigured.” Cracks had also appeared in the concrete, perhaps likewise caused by unrestrained hooligan skaters. “Those cracks and creases will probably be an ‘eye-sore’ for years,” the paper concluded.

Today the wheels of skateboards are more often blamed for damage, real or imagined, but roller skates and enticing stretches of concrete are still with us.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

A pair of roller skates within the permanent collection of The Children's Museum of Indianapolis. Roller skates were invented in the 1700s, but they didn’t really become popular until the 20th century. Skates like these fit on over your shoes and were adjustable.

Published on September 14, 2021 04:00

September 13, 2021

Russell and Her Rodeo

So, I was doing a little research on rodeos the other day because someone had a question about the Caldwell Night Rodeo (which I’ll address in a later post). I dug out my copy of Louise Shadduck’s book,

Rodeo Idaho

. As is usually the case when I set out to research something, I’m presented with rabbit trail after rabbit trail that I want to sniff down. For instance, did you know that Jane Russell came to Idaho to relax after making her first movie,

Outlaw

? It was a 1943 Howard Hughes film about Billy the Kid. Russell spent some time in Island Park where one of the locals pulled together a rodeo at her request. Shadduck’s book has a couple of pictures.

Shadduck’s book mentioned a couple of contenders for the first American rodeo, one in Prescott, Arizona in 1888 and Cheyenne’s Frontier Days, which started in 1897. She claimed that Idaho’s first rodeo began in 1906. That would become famous as Nampa’s Snake River Stampede. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Shadduck, but I thought I’d do my own quick search through Idaho papers, just to see if I found a mention of an earlier rodeo.

Wow! Right away I came up with one in or around Albion from 1880. Then, I started seeing others in subsequent years from all around the state. In a couple of minutes, I went from elation to minor disappointment. Yes, Idaho had earlier rodeos. Many of them. They weren’t going to count, though, because the early papers were using the word in its original meaning, which is roundup in Spanish. The papers were reporting on the annual roundups of cattle in certain areas, which were annual events. They still are, but newspapers have a lot more to talk about, these days.

So, I hadn’t made a startling discovery about the history of rodeos. Still, it gave me the opportunity to illustrate this post with a publicity photo of Jane Russell from Outlaw, which was probably what drew you to this story in the first place. ‘Fess up!

Shadduck’s book mentioned a couple of contenders for the first American rodeo, one in Prescott, Arizona in 1888 and Cheyenne’s Frontier Days, which started in 1897. She claimed that Idaho’s first rodeo began in 1906. That would become famous as Nampa’s Snake River Stampede. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe Shadduck, but I thought I’d do my own quick search through Idaho papers, just to see if I found a mention of an earlier rodeo.

Wow! Right away I came up with one in or around Albion from 1880. Then, I started seeing others in subsequent years from all around the state. In a couple of minutes, I went from elation to minor disappointment. Yes, Idaho had earlier rodeos. Many of them. They weren’t going to count, though, because the early papers were using the word in its original meaning, which is roundup in Spanish. The papers were reporting on the annual roundups of cattle in certain areas, which were annual events. They still are, but newspapers have a lot more to talk about, these days.

So, I hadn’t made a startling discovery about the history of rodeos. Still, it gave me the opportunity to illustrate this post with a publicity photo of Jane Russell from Outlaw, which was probably what drew you to this story in the first place. ‘Fess up!

Published on September 13, 2021 04:00

September 12, 2021

When the Stars (sort of) Came to Boise

February 20, 1940 was a much-anticipated date in Boise. That evening would be the world premiere of a major motion picture at the Pinney Theater.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whoever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

The movie was Northwest Passage, filmed around McCall, particularly in what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. It starred some big-name actors, Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey.

Based on a popular novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts, Northwest Passage was called an “epic” picture and “Hollywood’s Greatest Adventure Drama” in headlines leading up to the premiere. Roberts was billed as “America’s foremost historical novelist.”

Filming the movie had certainly been an epic adventure for the citizens of McCall. It was shot over two summer seasons. Some 900 locals worked as extras and at other jobs related to filming. The production set up shop on 50 acres bordering Payette Lake. Twelve freight cars brought in dozens of Indian drums, sugar kettles, gun racks, weaving frames, rush bottom chairs, spinning wheels, leather bellows, anvils, and 1,000 cannon balls. It was a virtual traveling museum including antique desks, tables and chests, pelts of every North American mammal worth mentioning, candlesticks, mahogany buckets, brass clocks, and on and on.

A blacksmith shop was built to look like it originated in 1750 for some of the movie scenes, and it was used to forge nails for the buildings the crew would set up. Every effort was made to assure the props looked like the real thing. Indian items were designed using tribal markings of the Abenakia (the setting for the movie was in Maine). For verisimilitude the 700 scalps hung from poles on the set were made with human hair, though the “scalps” were made of rubber.

The green buckskin uniforms Rogers’ Rangers wore in the movie seemed totally wrong to people used to brown or buttery yellow buckskin. In the book, Roberts had specified that they wore green buckskin, so MGM went with that, though it was a constant headache to keep the costumes dyed evenly.

This was to be two-time Academy Award-winner Spencer Tracy’s greatest role, playing Major Rogers, of Rogers’ Rangers. Legendary director King Vidor directed. So, the speculation in Boise was, who would show up for the premiere?

On January 10, Pinney Theater Manager J.R. Mendenhall announced that Robert Young would attend, along with others yet to be named. Also, yet to be named were the members of the local committee set up to plan the festivities surrounding the premiere. Governor C.A. Bottolfsen didn’t waste any time, naming Idahoans from Boise, Caldwell, Nampa, Weiser, Payette, and Emmett to the committee, with state Senator Carl E. Brown of McCall to head it. Brown, along with the McCall Chamber of Commerce and the Idaho Timber Protective Association had been instrumental in bringing the production to Payette Lake.

As the date approached there was continued speculation in The Idaho Statesman about who would attend. Would King Vidor be there? Tracy? Brennan? Young? There was also speculation about what reserved seats at the Pinney would cost, this during a time when a ticket to the movies was typically 15 cents. MGM, suggested $2.50 would be about right. The Pinney settled on $1.10, and assured those who might be outraged at the price that the film would stick around for at least a couple of weeks at regular prices.

Meanwhile, the Governor’s committee charged ahead with planning. The stars, whoever they were, would be greeted at the Boise Depot at 7:23 am by committee members and Mayor James L. Straight. Then, it was off to the Owyhee hotel for a breakfast to be attended by the committee members and their wives (no women were on the committee) and the stars. After breakfast the stars would be escorted (by the committee) to the governor’s office. All Idaho mayors were invited to be on hand for that meet and greet. Then, at 12:15 a public luncheon starring the stars would be sponsored by the Boise Chamber of Commerce, with tickets available to the masses. At 2 pm there would be a parade featuring high school students—participants in a costume contest—dressed in clothing as depicted in the movie. Along the way merchants were expected to have appropriate displays.

That evening, a radio broadcast would air from 8 until 8:30 outside the theater, around which would be Hollywood props and spotlights. Then, practically as an afterthought, they would show the film. The stars would catch the 11:20 out of town.

So, when the big day came, who of the Who’s Who showed up? Stars. Maybe none you’ve ever heard of, but it was still a big deal to welcome Ilona Massey, Virginia Grey, Alan Curtis, Isabel Jewell, and Nat Pendelton, luminaries all, to town. The crowd that came to see them was reportedly so enthusiastic that Boise’s new fire engine had to be called to rescue the actors, which was totally not a planned event. Certainly unplanned was the trampling of several cars when the star-struck climbed on hoods and roofs the better to capture a bit of stardust. And, as if to justify the firetruck, one of the klieg lights caught a tree branch on fire.

For those on tenterhooks, Shirley Weisgerber won the costume contest. Meanwhile, Spencer Tracy sent a telegram to the governor expressing his regrets for being unable to attend due to his “continued employment in Hollywood on Edison the Man.”

There was to be a sequel to Northwest Passage, but the studio never got around to making it. The movie won the Academy Award for best cinematography in 1941, in spite of the glowing green costumes.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

From left to right, Robert Young, Spencer Tracy, and Walter Brennan commiserate beneath a ponderosa pine on the set of Northwest Passage near McCall. The world premiere for the movie was held at the Pinney Theater in Boise.

Published on September 12, 2021 04:00

September 11, 2021

Murder and the Mayor

You might want to refill your coffee cup before reading today’s story. My posts are usually fairly short. This one just kept growing and growing as I learned more about the mayor and the murder.

Duncan McDougal Johnston was a WWI veteran who served in France with Battery B, 146th field artillery unit. He moved to Twin Falls from Boise in 1928 to open a jewelry store. By 1936 he was the Mayor of Twin Falls. That was the year he was briefly a candidate for congress in Idaho’s second congressional district, running against incumbent Congressman D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary. In April 1938 he was the toastmaster at the Jefferson Day banquet in Twin Falls, lauding Congressman Clark. By December of 1938, at age 39, he was the former mayor of Twin Falls and he had been convicted of murder.

Johnston was convicted of killing a jewelry salesman by the name of George L. Olson of Salt Lake. Olson was found locked in his car at a Twin Falls hotel some days after being shot in the head. About $18,000 worth of Olson’s jewelry along with a .25-caliber gun believed to have been the murder weapon were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store.

In one of many novel-worthy twists, the judge for Johnston’s trial, James W. Porter, had been the man’s commanding officer during the war.

Early in the investigation there was some question about Salt Lake City police officers getting involved with the case. Salt Lake City Police Bureau Sergeant Albert H. Roberts put that to rest when he said that Twin Falls Police Chief Howard Gillette “(knew) his onions” when it came to interviewing suspects. And, yes, I gratuitously included that otherwise unimportant quote simply because it sounded like something out of a Mickey Spillane novel.

It wasn’t the only pulp fiction moment. One headline in The Times News read, “Slain Man With Beautiful Boise Girl, Proprietors and Chef Assert.” The proprietors were Mr. and Mrs. Howard McKray, owners of the tourist park where Olson had stayed, and the chef worked at a nearby restaurant. They were witnesses who saw the beautiful girl.

“I know it was him because that was the name he used. He was registered with us from Salt Lake City, was a jewelry salesman, and the picture in the papers was an exact likeness of him,” Mrs. McKray told reporters. Breathlessly, perhaps.

“Olson ran up a bill of $16,” the chef said, “and finally he traded me a wedding ring and engagement ring which I am going to give to my girl, Flossie Colson, who is working for me, when I marry her.” No word on how Flossie felt about getting a $16 wedding set swapped for corned beef hash.

During the trial one witness was described—Spillane style—as “a pretty, bespectacled telephone operator.” The newspaper reporter noted that she gave one of her answers “with a toss of her head.”

Meanwhile, the victim’s wife was a “pretty, youthful widow” and another witness was described as “comely.”

Patrolman Craig T. Bracken was a key witness in the case. His role was to hide in the basement of the jewelry store and spy on Johnston. The basement was accessible not only from the jewelry store but from an adjacent dress shop. He watched the man come down the stairs, toss something in the furnace, then turn and stare at a break or crack in the basement wall for a few seconds. Johnston left, but came back down the stairs a few minutes later, again paying some attention to the hole in the wall. That’s when the jeweler noticed the patrolman hiding behind the furnace. Bracken called out to Johnston, saying “Well, Dunc, they put me down here to watch you and see what you were doing.” Bracken arrested Johnston and took him to the station. Chief Gillette and another patrolmen went to the store and into the basement where they found 557 rings tied up in a towel, keys to the murdered man’s car, and a .25-caliber pistol.

Johnston and his assistant in the Jewelry store, William LaVonde, were arrested on suspicion of murder. LaVonde was more than an assistant to Johnston. They had served in the war together and were long time buddies. LaVonde was also a former desk sergeant with the Twin Falls police.

The men, both well-known in the community, were arrested June 2. On June 6, while in jail, Johnston completed the sale of his jewelry store to Don Kugler, of Idaho Falls. Had Johnston’s business been in trouble? Was that a motive for murder and robbery?

There was no provision for posting bail in Idaho at the time when one was accused of first-degree murder. LaVonde, the assistant in the jewelry store, asked for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds there was no compelling evidence against him. On September 16, the Idaho Supreme Court granted his petition and LaVonde went free. But not for long. A revised complaint got him tossed back in jail on the 20th. But not for long. A judge freed him on the 26th citing a lack of evidence against LaVonde in the case, but at the same time binding over Johnston for trial.

Even in an agricultural community it was a little odd that twelve men—11 of them farmers and the 12th a retired farmer—would pass judgement on Johnston. They were particularly qualified to understand when one of the prosecution witnesses explained why pieces of earth found in the victim’s car had not been analyzed. “There’s a lot of dirt in Twin Falls County,” the witness said.

The prosecution was built largely on the fact that the stolen jewels, the victim’s car keys, and an alleged murder weapon—the FBI could not say whether or not it had been the one used—were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store. Meanwhile, the defense pointed out that furnace service men, the dress shop owners, employees of a Chinese restaurant, and a rooming house operator all had keys to the same basement.

The defense opted not to make a final statement in the trial, perhaps assuming that a case built on circumstantial evidence didn’t need a summation to point that out. Or, maybe it did. The jury came back after eight hours of deliberation with a guilty verdict. Johnston was sentenced to life in prison.

On December 15, 1938, Duncan Johnston greeted an old friend by saying, “Hello, Pearl,” and giving Pearl C. Meredith a smile. Meredith was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary.

In 1939, the Idaho Supreme Court ordered a retrial of Johnston, citing questionable testimony by the Twin Falls Chief of Police. Johnston spent much more time on the stand defending himself in this trial. It didn’t help. He was found guilty, again. Johnston appealed, again, to the Idaho Supreme Court.

Then the confession showed up. On March 19, 1941, Governor Chase Clark received a note using letters cut from The Salt Lake Tribune and pasted on the paper in the fashion of a ransom demand. The anonymous message sender claimed that Johnston was the victim of a “vicious frame-up.” Although a cut-up Salt Lake newspaper was used, the letter came from Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Though interesting, the note proved nothing. The supreme court denied Johnston a third trial.

So, in December of 1941, the convicted murderer petitioned the pardon board for clemency.

At his January 1942 hearing, Johnston stood up to give an impassioned speech as the pardon board was rising to leave. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “Three and one-half years ago, or a little more, I sat as you gentlemen here today. My word had never been doubted. My integrity was as high… as anyone.

“From the time I was arrested until the present day, I have been a dastardly liar. I have been a Capone. I have been the coldest blooded murderer in the State of Idaho. Dillinger is a sissy to the side of me…

“You gentlemen have no idea what it means to sit behind bars and listen to the clang of chains and keys, when you did not commit the crime that was framed against you. It is almost unbelievable that in the United States, where we criticize the Nazis and the Gestapo, that you can find it right here in your own community.”

His pardon was denied by a 2-1 vote of the board.

He was back, again, in April asking for a pardon. Again, the vote was 2-1 against.

Then, there was a new twist. On December 21, 1942, the front-page headline spread across eight columns in The Statesman read, “Duncan Johnston Escapes From Prison.”

Under the cover of “pea-soup” fog, Johnston ran through the freshly fallen snow to an awaiting car in the 1400 block of East Washington and made his escape. He had constructed a dummy to occupy his bed during his getaway. His breakout was made easier because he wasn’t living in the prison. Johnston was a trusty residing in a small house adjacent to the hot-water pumps that supplied water to Warm Springs Avenue homes.

At least, that was the sensational story on December 21. By the next day, the front-page story was not nearly so dramatic. The headline read, “Johnston Returns to Cell After Going Bye-Bye Third Time.” Wait. Third time? Yes, it turned out Johnston had walked away a couple of other times, visiting Public School Field and the Ada County Courthouse the previous two times. The warden had neglected to mention those incidents. Johnston wasn’t captured. He simply walked back to the prison after spending seven hours walking around trying to “relieve a feeling of despondency” over his prison term.

So, pardon was probably off the table, right? Stand by.

His appeal for pardon that December, which happened to be decided the day after he walked away—and back—was denied.

His fourth application for pardon came in April 1943. It was denied.

In July 1943, the board denied his fifth application. His six application was denied that October.

On his seventh application, the board vote flipped in Johnston’s favor when Attorney General Bert H. Miller changed his vote. Why? He had determined through exhaustive investigation that several jurors as well as the prosecutors, were not convinced that Johnston had fired the fatal shot. Miller thought there was no proof he had fired the shot, and therefore Johnston had not been proved guilty. Miller was quoted in The Times News as saying, “I am not voting to pardon Johnston, but to release him from punishment for a crime for which he was unjustly convicted.”

Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Merrill, of Ketchum, had taken on Johnston’s case almost as a hobby, continuing to pester the pardon board time after time. They truly believed in his innocence and didn’t have a personal dog in the fight. They didn’t even know Johnston before he was imprisoned.

Johnston was grateful to the Merrills, but remained bitter, saying he wanted a reversal of his murder conviction in court instead of a pardon. “Naturally, I am terribly thankful for my freedom,” he said, “And it is hard to say thanks for something you don’t want—that is, I am glad to be free, but I didn’t want it to come this way.”

Johnston planned to go into defense work for the military, perhaps in California. “I went through five campaigns in the last war and came out a disabled veteran. Nothing would please me more than to do something in this campaign.”

Whether Johnston ever served in any capacity in WWII is unknown. He apparently left Idaho shortly after his pardon. His grandniece contacted me after this story ran the first time to say that he had operated a successful jewelry store in the Mission District of San Francisco for many years. He lived to be 90, passing away in San Mateo California in 1989.

The Olson murder case was never reopened.

But what of Attorney General Bert H. Miller? Many were outraged at his vote that set Johnston free. There were grumblings that his time as attorney general would soon be over. It was, but not in the way those who disagreed with him on the Johnston case might have hoped. He was elected a justice of Idaho’s Supreme Court in 1944, then elected a U.S. senator from Idaho in 1948, defeating Senator Henry Dworshak. Miller served only nine months in that office before dying of a heart attack. In a twist that probably ruffled a few feathers, Governor C.A. Robbins appointed Dworshak, the man Miller narrowly defeated, to fill out his term. Dworshak would remain a senator until 1962, when he, too, died of a heart attack while in office.

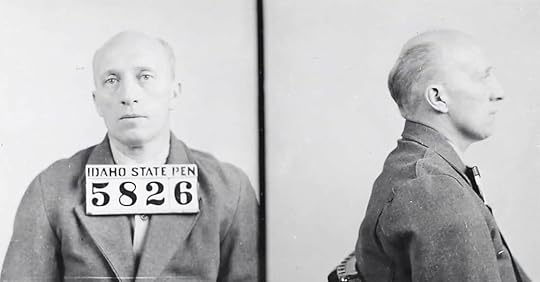

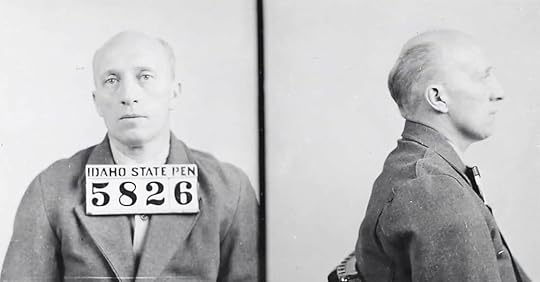

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Duncan McDougal Johnston was a WWI veteran who served in France with Battery B, 146th field artillery unit. He moved to Twin Falls from Boise in 1928 to open a jewelry store. By 1936 he was the Mayor of Twin Falls. That was the year he was briefly a candidate for congress in Idaho’s second congressional district, running against incumbent Congressman D. Worth Clark in the Democratic primary. In April 1938 he was the toastmaster at the Jefferson Day banquet in Twin Falls, lauding Congressman Clark. By December of 1938, at age 39, he was the former mayor of Twin Falls and he had been convicted of murder.

Johnston was convicted of killing a jewelry salesman by the name of George L. Olson of Salt Lake. Olson was found locked in his car at a Twin Falls hotel some days after being shot in the head. About $18,000 worth of Olson’s jewelry along with a .25-caliber gun believed to have been the murder weapon were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store.

In one of many novel-worthy twists, the judge for Johnston’s trial, James W. Porter, had been the man’s commanding officer during the war.

Early in the investigation there was some question about Salt Lake City police officers getting involved with the case. Salt Lake City Police Bureau Sergeant Albert H. Roberts put that to rest when he said that Twin Falls Police Chief Howard Gillette “(knew) his onions” when it came to interviewing suspects. And, yes, I gratuitously included that otherwise unimportant quote simply because it sounded like something out of a Mickey Spillane novel.

It wasn’t the only pulp fiction moment. One headline in The Times News read, “Slain Man With Beautiful Boise Girl, Proprietors and Chef Assert.” The proprietors were Mr. and Mrs. Howard McKray, owners of the tourist park where Olson had stayed, and the chef worked at a nearby restaurant. They were witnesses who saw the beautiful girl.

“I know it was him because that was the name he used. He was registered with us from Salt Lake City, was a jewelry salesman, and the picture in the papers was an exact likeness of him,” Mrs. McKray told reporters. Breathlessly, perhaps.

“Olson ran up a bill of $16,” the chef said, “and finally he traded me a wedding ring and engagement ring which I am going to give to my girl, Flossie Colson, who is working for me, when I marry her.” No word on how Flossie felt about getting a $16 wedding set swapped for corned beef hash.

During the trial one witness was described—Spillane style—as “a pretty, bespectacled telephone operator.” The newspaper reporter noted that she gave one of her answers “with a toss of her head.”

Meanwhile, the victim’s wife was a “pretty, youthful widow” and another witness was described as “comely.”

Patrolman Craig T. Bracken was a key witness in the case. His role was to hide in the basement of the jewelry store and spy on Johnston. The basement was accessible not only from the jewelry store but from an adjacent dress shop. He watched the man come down the stairs, toss something in the furnace, then turn and stare at a break or crack in the basement wall for a few seconds. Johnston left, but came back down the stairs a few minutes later, again paying some attention to the hole in the wall. That’s when the jeweler noticed the patrolman hiding behind the furnace. Bracken called out to Johnston, saying “Well, Dunc, they put me down here to watch you and see what you were doing.” Bracken arrested Johnston and took him to the station. Chief Gillette and another patrolmen went to the store and into the basement where they found 557 rings tied up in a towel, keys to the murdered man’s car, and a .25-caliber pistol.

Johnston and his assistant in the Jewelry store, William LaVonde, were arrested on suspicion of murder. LaVonde was more than an assistant to Johnston. They had served in the war together and were long time buddies. LaVonde was also a former desk sergeant with the Twin Falls police.

The men, both well-known in the community, were arrested June 2. On June 6, while in jail, Johnston completed the sale of his jewelry store to Don Kugler, of Idaho Falls. Had Johnston’s business been in trouble? Was that a motive for murder and robbery?

There was no provision for posting bail in Idaho at the time when one was accused of first-degree murder. LaVonde, the assistant in the jewelry store, asked for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds there was no compelling evidence against him. On September 16, the Idaho Supreme Court granted his petition and LaVonde went free. But not for long. A revised complaint got him tossed back in jail on the 20th. But not for long. A judge freed him on the 26th citing a lack of evidence against LaVonde in the case, but at the same time binding over Johnston for trial.

Even in an agricultural community it was a little odd that twelve men—11 of them farmers and the 12th a retired farmer—would pass judgement on Johnston. They were particularly qualified to understand when one of the prosecution witnesses explained why pieces of earth found in the victim’s car had not been analyzed. “There’s a lot of dirt in Twin Falls County,” the witness said.

The prosecution was built largely on the fact that the stolen jewels, the victim’s car keys, and an alleged murder weapon—the FBI could not say whether or not it had been the one used—were found in the basement of Johnston’s jewelry store. Meanwhile, the defense pointed out that furnace service men, the dress shop owners, employees of a Chinese restaurant, and a rooming house operator all had keys to the same basement.

The defense opted not to make a final statement in the trial, perhaps assuming that a case built on circumstantial evidence didn’t need a summation to point that out. Or, maybe it did. The jury came back after eight hours of deliberation with a guilty verdict. Johnston was sentenced to life in prison.

On December 15, 1938, Duncan Johnston greeted an old friend by saying, “Hello, Pearl,” and giving Pearl C. Meredith a smile. Meredith was the warden of the Idaho State Penitentiary.

In 1939, the Idaho Supreme Court ordered a retrial of Johnston, citing questionable testimony by the Twin Falls Chief of Police. Johnston spent much more time on the stand defending himself in this trial. It didn’t help. He was found guilty, again. Johnston appealed, again, to the Idaho Supreme Court.

Then the confession showed up. On March 19, 1941, Governor Chase Clark received a note using letters cut from The Salt Lake Tribune and pasted on the paper in the fashion of a ransom demand. The anonymous message sender claimed that Johnston was the victim of a “vicious frame-up.” Although a cut-up Salt Lake newspaper was used, the letter came from Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Though interesting, the note proved nothing. The supreme court denied Johnston a third trial.

So, in December of 1941, the convicted murderer petitioned the pardon board for clemency.

At his January 1942 hearing, Johnston stood up to give an impassioned speech as the pardon board was rising to leave. The Idaho Statesman quoted him as saying, “Three and one-half years ago, or a little more, I sat as you gentlemen here today. My word had never been doubted. My integrity was as high… as anyone.

“From the time I was arrested until the present day, I have been a dastardly liar. I have been a Capone. I have been the coldest blooded murderer in the State of Idaho. Dillinger is a sissy to the side of me…

“You gentlemen have no idea what it means to sit behind bars and listen to the clang of chains and keys, when you did not commit the crime that was framed against you. It is almost unbelievable that in the United States, where we criticize the Nazis and the Gestapo, that you can find it right here in your own community.”

His pardon was denied by a 2-1 vote of the board.

He was back, again, in April asking for a pardon. Again, the vote was 2-1 against.

Then, there was a new twist. On December 21, 1942, the front-page headline spread across eight columns in The Statesman read, “Duncan Johnston Escapes From Prison.”

Under the cover of “pea-soup” fog, Johnston ran through the freshly fallen snow to an awaiting car in the 1400 block of East Washington and made his escape. He had constructed a dummy to occupy his bed during his getaway. His breakout was made easier because he wasn’t living in the prison. Johnston was a trusty residing in a small house adjacent to the hot-water pumps that supplied water to Warm Springs Avenue homes.

At least, that was the sensational story on December 21. By the next day, the front-page story was not nearly so dramatic. The headline read, “Johnston Returns to Cell After Going Bye-Bye Third Time.” Wait. Third time? Yes, it turned out Johnston had walked away a couple of other times, visiting Public School Field and the Ada County Courthouse the previous two times. The warden had neglected to mention those incidents. Johnston wasn’t captured. He simply walked back to the prison after spending seven hours walking around trying to “relieve a feeling of despondency” over his prison term.

So, pardon was probably off the table, right? Stand by.

His appeal for pardon that December, which happened to be decided the day after he walked away—and back—was denied.

His fourth application for pardon came in April 1943. It was denied.

In July 1943, the board denied his fifth application. His six application was denied that October.

On his seventh application, the board vote flipped in Johnston’s favor when Attorney General Bert H. Miller changed his vote. Why? He had determined through exhaustive investigation that several jurors as well as the prosecutors, were not convinced that Johnston had fired the fatal shot. Miller thought there was no proof he had fired the shot, and therefore Johnston had not been proved guilty. Miller was quoted in The Times News as saying, “I am not voting to pardon Johnston, but to release him from punishment for a crime for which he was unjustly convicted.”

Mr. and Mrs. C.D. Merrill, of Ketchum, had taken on Johnston’s case almost as a hobby, continuing to pester the pardon board time after time. They truly believed in his innocence and didn’t have a personal dog in the fight. They didn’t even know Johnston before he was imprisoned.

Johnston was grateful to the Merrills, but remained bitter, saying he wanted a reversal of his murder conviction in court instead of a pardon. “Naturally, I am terribly thankful for my freedom,” he said, “And it is hard to say thanks for something you don’t want—that is, I am glad to be free, but I didn’t want it to come this way.”

Johnston planned to go into defense work for the military, perhaps in California. “I went through five campaigns in the last war and came out a disabled veteran. Nothing would please me more than to do something in this campaign.”

Whether Johnston ever served in any capacity in WWII is unknown. He apparently left Idaho shortly after his pardon. His grandniece contacted me after this story ran the first time to say that he had operated a successful jewelry store in the Mission District of San Francisco for many years. He lived to be 90, passing away in San Mateo California in 1989.

The Olson murder case was never reopened.

But what of Attorney General Bert H. Miller? Many were outraged at his vote that set Johnston free. There were grumblings that his time as attorney general would soon be over. It was, but not in the way those who disagreed with him on the Johnston case might have hoped. He was elected a justice of Idaho’s Supreme Court in 1944, then elected a U.S. senator from Idaho in 1948, defeating Senator Henry Dworshak. Miller served only nine months in that office before dying of a heart attack. In a twist that probably ruffled a few feathers, Governor C.A. Robbins appointed Dworshak, the man Miller narrowly defeated, to fill out his term. Dworshak would remain a senator until 1962, when he, too, died of a heart attack while in office.

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Duncan McDougal Johnston's prison mugshot, 1938.

Published on September 11, 2021 04:00

September 10, 2021

Lulu Bell Parr

The myth of the Wild West became so ingrained in the story of our country that it sold well even in the West itself. Dime novels were popular everywhere and while cowboys were still plentiful on the range—they’re still not rare—wild west shows played to packed arenas.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show made at least one stop in Idaho Falls in the early part of the Twentieth Century. A competing spectacle, the “101 Ranch Show” played in Boise on June 17, 1912, a time when wagons were still more common than automobiles on the streets.

The 101 Ranch was a real place, an 87,000-acre spread in northeastern Oklahoma that was the largest diversified farm and ranch at the time, boasting, according to a 1905 Idaho Statesman article, 9,000 acres of wheat, 3,000 acres of corn, and 10,000 head of longhorn cattle. The wild west show was just one of their many enterprises.

During its 1912 visit to Boise the paper carried stories about the “Dare Devil Girls” of the 101 Ranch. The best-known cowgirl appearing was Lulu Bell Parr, who had also appeared in the Buffalo Bill’s shows. Lulu was your typical cowgirl, having grown up in Indiana, moving to Ohio when she got married in 1896. She was divorced in 1902 and by 1903 she was travelling in Europe with Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show.

The Statesman reported that she was one of the most “fearless riders and skillful manipulators of the lariat, [and was] to the manor born, for much of her life has been spent on a ranch, and the ranch life appeals to her as the only one that is really worthwhile.” One could be forgiven for wondering why she was performing in a string of wild west shows if green acres was the only place to be.

Still, she was a superb rider. “Many times,” the article said, “both on the cattle range and in the exhibitions of the 101 Ranch, Miss Parr has courted injury and possible death by her daredevil riding.” The preceding spring, in that well-known Cowtown, Philadelphia, she dared to ride “an outlaw pony that had defied nearly all the cowboys and other rough riders. She made the attempt and would have achieved an immediate victory over the vicious animal if her saddle girth had not slipped and thrown her to the ground. Notwithstanding the fact that she was momentarily stunned and received numerous painful bruises, the plucky little rider attempted the feat again the next day and triumphed over the animal.”

The wild west shows dwindled in popularity. By 1929 they were about dead. Lulu Bell Parr retired, broke and discouraged. She settled in Ohio where she lived with her brother until her death in 1960 at age 84.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show made at least one stop in Idaho Falls in the early part of the Twentieth Century. A competing spectacle, the “101 Ranch Show” played in Boise on June 17, 1912, a time when wagons were still more common than automobiles on the streets.

The 101 Ranch was a real place, an 87,000-acre spread in northeastern Oklahoma that was the largest diversified farm and ranch at the time, boasting, according to a 1905 Idaho Statesman article, 9,000 acres of wheat, 3,000 acres of corn, and 10,000 head of longhorn cattle. The wild west show was just one of their many enterprises.

During its 1912 visit to Boise the paper carried stories about the “Dare Devil Girls” of the 101 Ranch. The best-known cowgirl appearing was Lulu Bell Parr, who had also appeared in the Buffalo Bill’s shows. Lulu was your typical cowgirl, having grown up in Indiana, moving to Ohio when she got married in 1896. She was divorced in 1902 and by 1903 she was travelling in Europe with Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show.

The Statesman reported that she was one of the most “fearless riders and skillful manipulators of the lariat, [and was] to the manor born, for much of her life has been spent on a ranch, and the ranch life appeals to her as the only one that is really worthwhile.” One could be forgiven for wondering why she was performing in a string of wild west shows if green acres was the only place to be.

Still, she was a superb rider. “Many times,” the article said, “both on the cattle range and in the exhibitions of the 101 Ranch, Miss Parr has courted injury and possible death by her daredevil riding.” The preceding spring, in that well-known Cowtown, Philadelphia, she dared to ride “an outlaw pony that had defied nearly all the cowboys and other rough riders. She made the attempt and would have achieved an immediate victory over the vicious animal if her saddle girth had not slipped and thrown her to the ground. Notwithstanding the fact that she was momentarily stunned and received numerous painful bruises, the plucky little rider attempted the feat again the next day and triumphed over the animal.”

The wild west shows dwindled in popularity. By 1929 they were about dead. Lulu Bell Parr retired, broke and discouraged. She settled in Ohio where she lived with her brother until her death in 1960 at age 84.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Publicity photo of Lulu Bell Parr in her heyday.

Published on September 10, 2021 04:00

September 9, 2021

Louise Shadduck

Louise Shadduck wore a lot of hats, figuratively, and not rarely her favorite cowboy hat. She wrote the book

Rodeo Idaho

! She also wrote

Andy Little, Idaho Sheep King

,

Doctors With Buggies, Snowshoes, and Planes

,

The House that Victor Built

and

At the Edge of the Ice

.* Mike Bullard wrote a book about her called

Lioness of Idaho

.*

Shadduck, born in Coeur d’Alene in 1915, started out as a journalist. She wrote first for The Spokesman Review, then her hometown paper, The Coeur d’Alene Press. It was while working for The Press that she got her first taste of politics, covering the Republican National Convention in 1944. Inspired, she founded the Kootenai County Young Republicans. Then, she served a dual role working as a journalist while serving as an intern in Senator Henry Dworshak’s Washington, DC office.

In 1946 Shadduck took a job with Idaho Governor Charles Robbins, serving first as a publicity assistant, then as his administrative assistant. She was the first female to serve as a governor’s administrative assistant in Idaho. It wouldn’t be her last first. During her stint in the governor’s office she wrote a freelance column for The Coeur d’Alene Press called “This and That.”

When Len B. Jordan followed Robbins as governor, he retained Shadduck in her administrative assistant position. Then, in 1952, Senator Dworshak talked her into moving back to DC. There she became friends with Dwight Eisenhower. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in a televised address in 1952 in support of Eisenhower.

Shadduck decided to dive into politics herself, running for Idaho’s First Congressional District seat against Democrat Gracie Pfost. She lost that race, but it was another first for her. The match was the first time two women ran against each other for a congressional seat in US history. She spoke again for Eisenhower at the 1956 Republican National Convention, but her political future was to be on the state level.

Governor Robert E. Smylie appointed Shadduck to head the Idaho Department of Commerce and Development in 1958, making her the first woman in the country to serve in a state cabinet position. She was instrumental in bringing the National Girl Scout Roundup and the World Boy Scout Jamboree to Farragut State Park in 1965 and 1967, respectively.

Following Smylie’s last term in office she went to work as an administrative assistant to Congressman Orval Hansen.

Shadduck was troubled by the rise of white supremacists in her home state. She lobbied for a change in the malicious harassment law. That law was critical in putting the Aryan Nations out of business.

In her spare time, Shadduck served as president of the National Federation of Press Women from 1971 to 1973.

Shadduck never married. Upon her death in 2008, her great niece was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “it was because no man could keep up with her.”

Louise Shadduck

Louise Shadduck

Shadduck, born in Coeur d’Alene in 1915, started out as a journalist. She wrote first for The Spokesman Review, then her hometown paper, The Coeur d’Alene Press. It was while working for The Press that she got her first taste of politics, covering the Republican National Convention in 1944. Inspired, she founded the Kootenai County Young Republicans. Then, she served a dual role working as a journalist while serving as an intern in Senator Henry Dworshak’s Washington, DC office.

In 1946 Shadduck took a job with Idaho Governor Charles Robbins, serving first as a publicity assistant, then as his administrative assistant. She was the first female to serve as a governor’s administrative assistant in Idaho. It wouldn’t be her last first. During her stint in the governor’s office she wrote a freelance column for The Coeur d’Alene Press called “This and That.”

When Len B. Jordan followed Robbins as governor, he retained Shadduck in her administrative assistant position. Then, in 1952, Senator Dworshak talked her into moving back to DC. There she became friends with Dwight Eisenhower. She spoke at the Republican National Convention in a televised address in 1952 in support of Eisenhower.

Shadduck decided to dive into politics herself, running for Idaho’s First Congressional District seat against Democrat Gracie Pfost. She lost that race, but it was another first for her. The match was the first time two women ran against each other for a congressional seat in US history. She spoke again for Eisenhower at the 1956 Republican National Convention, but her political future was to be on the state level.

Governor Robert E. Smylie appointed Shadduck to head the Idaho Department of Commerce and Development in 1958, making her the first woman in the country to serve in a state cabinet position. She was instrumental in bringing the National Girl Scout Roundup and the World Boy Scout Jamboree to Farragut State Park in 1965 and 1967, respectively.

Following Smylie’s last term in office she went to work as an administrative assistant to Congressman Orval Hansen.

Shadduck was troubled by the rise of white supremacists in her home state. She lobbied for a change in the malicious harassment law. That law was critical in putting the Aryan Nations out of business.

In her spare time, Shadduck served as president of the National Federation of Press Women from 1971 to 1973.

Shadduck never married. Upon her death in 2008, her great niece was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, “it was because no man could keep up with her.”

Louise Shadduck

Louise Shadduck

Published on September 09, 2021 04:00

September 8, 2021

A Simple Basque Sheepherder

Jose “Joe” Bengoechea was a Basque sheepherder. Maybe it should be said that he was the Basque sheepherder. He came to the US in 1881 at age 20. He started herding sheep in Nevada, saving his money, and began buying sheep. His herds grew and he helped others from the Basque Country to immigrate.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.  The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

In addition to running sheep, and more sheep, he built the Bengoechea Hotel in 1910 in Mountain Home, ordering the best furnishings available. It first served as a Basque boarding house, as well as the residence of Jose and his family. Other residents often received help from Bengoechea when they needed it.

Bengoechea got his first car in 1900, when there were only about 14,000 cars in the country. Joe didn’t drive, but that didn’t stop him from getting around. He hired drivers. As one of the few people who had a lot of experience with cars he was often asked which car was best. He would always give the same answer: “A new one.”

By 1917, Jose Bengoechea was the richest man in Idaho. He owned several ranches, the hotel, and interests in many banks. He had five high-powered cars. His young wife had a large selection of furs and jewelry. Nothing was too expensive for his family and his friends.

That was when his good fortune ran out. Bengoechea had been selling sheep at high prices to the Army during the war. As the fighting came to an end, he envisioned even more profits ahead because of the need to feed a hungry Europe. He and other investors kept buying and buying. The bottom dropped out of the sheep and wool markets and suddenly the richest man in Idaho was bankrupt. His bankruptcy was pivotal in bringing down 27 banks in the state.

In 1921, the headlines read, “Richest Man in Idaho Only Four Years Ago, Basque Dies Broke.” He was 60.

Bengoechea’s hotel still stands as a symbol of his legacy at 195 North Second West in Mountain Home. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

Thanks to Patty Miller, director of Boise’s Basque Museum and Cultural Center for linking me to some of the information for this post.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.

Jose Bengoechea and his bride Margarita Achaval, wed in 1915.  The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

The Bengoechea Hotel building in Mountain Home.

Published on September 08, 2021 04:00

September 7, 2021

The First Idaho Flight

Idaho has a rich aviation history with solid connections to “Pappy” Boyington, Edward Pangborn, and Hawthorne Gray, to name a few daring pilots. The first contract air mail service in the United States was based in Boise with Varney Airlines. United Airlines claims Boise as its historical home, tracing its roots back to Varney.

But when was that first Idaho flight, the inception as it were of Idaho aviation history?

The Idaho Statesman declared, in an article on April 20, 1911, that Walter Brookins had launched into the air on “the first aeroplane flight ever made in the Gem state” the day before. This, in spite of the fact that the same paper had reported on October 16, 1910, that several flights had taken place above the fairgrounds in Lewiston, the last one ending in disaster.

Lewiston, still smarting today more than 150 years after losing the territorial capital, could be forgiven for being a little perturbed at this oversight.

James J. Ward of Chicago made the first Idaho flight on October 13, 1910. In Lewiston. His engine sputtered, causing him to land a little rougher than he’d hoped and destroying the front wheel of the Curtiss biplane. There were plenty of bicycle wheels in Lewiston, so that was easily replaced. He made several successful flights for the cheering crowd in the grandstand at the Lewiston-Clarkston fairgrounds.

His luck ran out, some would say, on October 14. His engine conked out when he was some 200 feet in the air. That was unlucky. But, luckily, Ward was able to jump free of the plane just as it crashed sustaining only minor injuries. The Idaho Statesman printed a dispatch from Lewiston that read, “The Curtiss biplane with which J.J. Ward of Chicago has been making daily flights at the fair, tonight lies a heap of junk on the banks of the Snake River, and that Ward himself is not in the morgue or at the hospital, is almost a miracle.”

Lewiston can also claim the first attempted flight in Idaho, though it was going to be just a glide. That came about on July 30, 1904, less than a year after the first successful flight of the Wright brothers. Captain Stewart V. Winslow, who during his working hours operated a dredge in the Snake River, tried to get into the air by pedaling a bicycle with wings over a cliff. He planned to glide across the river to the Washington side in triumph. He may have considered it bad luck when his front bicycle wheel collapsed before he could ride the contraption off the cliff. Luckily, he never did make a second try.

But what about that 1911 flight in Boise? It didn’t qualify as the first in the state, but it was the first in Boise, and it was accomplished by an aviation pioneer.

Walter Brookins, the first pilot trained by the Wright brothers, took to the air a few minutes after 5 pm on April 19, 1911 from the center field of the racetrack at the fairgrounds in Boise. Note that the fairgrounds were not located where they are today. They were roughly on the corner of Orchard and Fairview, thus the name of the latter street.

Promoters of the spectacle had cancelled the flight, allegedly because the weather had turned too cold for spectators. The many spectators who had shown up began to grumble and speculate that brisk winds were the real reason for the cancellation and casting aspersions on the pilot. When Brookins heard this he immediately rolled out his biplane and made preparations to meet the winds, which were described as gale force, head on.

One spectator was particularly interested in how Brookins would take to the Boise air. W.O. Kay, of Ogden, Utah, had followed the aviator to Boise, disappointed because he had not been able to take a ride in the Wright Biplane when Brookins had flown in Utah. Kay, who weighed 164 pounds, would have been too great a load for the plane to get into the air over Utah’s capital city. The air was too thin to keep both men aloft at Salt Lake’s elevation of 4,220 feet. Kay and Brookins both thought Boise’s 2,730-foot elevation would allow a passenger.

Without a hint of drama Brookins rolled along in the rough pasture for about 200 feet and rose steadily into the air. He would fly around the racetrack five times, a distance of about three miles, before an easy landing. He could not resist putting on a show for the crowd.