Rick Just's Blog, page 112

October 28, 2021

The Last Swim of Mr. Swim (Tap to read)

Isaac T. Swim was a prospector who, like most prospectors, hadn't done very well. In 1881, his luck changed.

Swim camped near the mouth of the Yankee Fork. A tremendous wind and rainstorm kept him there an extra day. When he woke up the next morning, he discovered that the wind had blown down branches and trees all around him. But that wasn't all he discovered. Beneath the roots of an uprooted tree, Isaac Swim discovered the glitter of gold.

The prospector blazed trees in the area so he could be certain of finding his way back. Then he set out for Challis, where he filed a mining claim on September 9, 1881.

Swim returned to his claim and gathered some choice samples of quartz generously flecked with gold. When he brought that back to civilization, it set men's imaginations to running wild. His grubstake partners were elated. They could hardly wait for spring.

Swim tried to lead his partners back to the claim in June 1882. Some stories say that a gaggle of miners also followed Swim, hoping to cash in.

The Salmon River was roaring with spring run-off. Eager to get back to his claim, Swim risked the river astride his horse. No one saw him drown, but it seems certain that the man named Swim was swept away in the river.

His partners went on to the area where Swim had discovered the vein. They found at least one of his tree blazes, but they didn't locate any gold.

Swim’s horse turned up months later, 50 miles downstream, lodged in driftwood. A body thought to be Swim’s turned up that summer in the Salmon River about 12 miles southwest of Challis. The site is called Dead Man’s Hole (photo). A BLM campground is there today.

Meanwhile, the Lost Swim Mine is still out there for the finding.

Swim camped near the mouth of the Yankee Fork. A tremendous wind and rainstorm kept him there an extra day. When he woke up the next morning, he discovered that the wind had blown down branches and trees all around him. But that wasn't all he discovered. Beneath the roots of an uprooted tree, Isaac Swim discovered the glitter of gold.

The prospector blazed trees in the area so he could be certain of finding his way back. Then he set out for Challis, where he filed a mining claim on September 9, 1881.

Swim returned to his claim and gathered some choice samples of quartz generously flecked with gold. When he brought that back to civilization, it set men's imaginations to running wild. His grubstake partners were elated. They could hardly wait for spring.

Swim tried to lead his partners back to the claim in June 1882. Some stories say that a gaggle of miners also followed Swim, hoping to cash in.

The Salmon River was roaring with spring run-off. Eager to get back to his claim, Swim risked the river astride his horse. No one saw him drown, but it seems certain that the man named Swim was swept away in the river.

His partners went on to the area where Swim had discovered the vein. They found at least one of his tree blazes, but they didn't locate any gold.

Swim’s horse turned up months later, 50 miles downstream, lodged in driftwood. A body thought to be Swim’s turned up that summer in the Salmon River about 12 miles southwest of Challis. The site is called Dead Man’s Hole (photo). A BLM campground is there today.

Meanwhile, the Lost Swim Mine is still out there for the finding.

Published on October 28, 2021 05:00

October 27, 2021

Idaho's Confusing Forts (Tap to Read)

One of the most confusing things about Idaho history is keeping track of the entangled relationship of two southern Idaho institutions called Fort Hall and Fort Boise. Fort Hall came first, and its creation led almost immediately to the creation of Fort Boise.

Neither fort had a military connection at first. Neither was much of a fort. Fort Boise was a collection of sticks and poles cobbled into an enclosure about 100 feet square. Within the enclosure were a handful of shacks built of the same materials, almost as if nesting birds designed the whole thing. Fort Hall was, arguably, a little better structure in the beginning, with palisade walls enclosing a few cabins.

In the 1830s Britain and the United States were quibbling over where the border should be in what we today call the Pacific Northwest. So, it was significant when Nathanial Wyeth established a trading post along the Snake River near its confluence with the Portneuf. Fort Hall, near present day Pocatello, was named after Hall J. Kelley, who had recruited Wyeth to go west to establish a trading post. When Wyeth tamped the posts in that palisade wall down and opened the gates for business, Fort Hall became the only outpost with ties to the United States in Oregon country.

The British Hudson’s Bay Company saw Fort Hall as a challenge to their trading dominance in the region, so in the fall of 1834, they patched together a trading post near the confluence of the Snake and Boise rivers, taking the name of the latter for their Fort Boise. Francois Payette ran Fort Boise until 1844, mostly with a “staff” of traders from Hawaii. After a few years Payette moved the operation to another nearby site and constructed a much more substantial post, eventually surrounding it with sun-dried adobe brick.

Wyeth and his operation, meanwhile, lasted only until 1837, when he sold Fort Hall and a second trading post he had built on the Columbia, to the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The US settled the boundary dispute with the British in 1846, establishing the border we know today between Washington and Canada. That opened up a torrent of settlers headed west into Oregon Country. Both forts became important replenishment points for emigrants. Fort Boise was famous for welcoming Oregon Trail travelers and providing them with needed provisions.

Fort Boise, the trading post near present day Parma, fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles. The original Fort Hall fell to a flood in 1863. A nearby replacement served emigrants for a few more years.

So, both forts, Hall and Boise, operated from about 1834, mostly as trading posts from about their original locations. Then it got confusing.

The military established the new Fort Boise in 1863 along the foothills north of the Boise River. The town of Boise sprung up below the fort.

In 1870, the US Army established a military post near the Blackfoot River about 25 miles from old Fort Hall. Rather than name the new post after some forgotten general, they called that one Fort Hall, too. In order to completely perplex students of history, the main town on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation also became Fort Hall. Then, to better tell the story of Fort Hall, history enthusiasts built a faithful replica of old Fort Hall near the zoo in Pocatello.

So, if someone mentions Fort Hall, ask them which one they’re referencing. Do they mean the reservation, the town, the old fort, the military fort, or the replica?

For Fort Boise, you only have to ask whether they mean the military fort or the trading post. Or, I suppose, the replica, which lurks near the trading post’s original location in Parma.

This 1849 lithograph shows Fort Boise, the trading post near Parma, in its prime. It fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles.

This 1849 lithograph shows Fort Boise, the trading post near Parma, in its prime. It fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles.

Neither fort had a military connection at first. Neither was much of a fort. Fort Boise was a collection of sticks and poles cobbled into an enclosure about 100 feet square. Within the enclosure were a handful of shacks built of the same materials, almost as if nesting birds designed the whole thing. Fort Hall was, arguably, a little better structure in the beginning, with palisade walls enclosing a few cabins.

In the 1830s Britain and the United States were quibbling over where the border should be in what we today call the Pacific Northwest. So, it was significant when Nathanial Wyeth established a trading post along the Snake River near its confluence with the Portneuf. Fort Hall, near present day Pocatello, was named after Hall J. Kelley, who had recruited Wyeth to go west to establish a trading post. When Wyeth tamped the posts in that palisade wall down and opened the gates for business, Fort Hall became the only outpost with ties to the United States in Oregon country.

The British Hudson’s Bay Company saw Fort Hall as a challenge to their trading dominance in the region, so in the fall of 1834, they patched together a trading post near the confluence of the Snake and Boise rivers, taking the name of the latter for their Fort Boise. Francois Payette ran Fort Boise until 1844, mostly with a “staff” of traders from Hawaii. After a few years Payette moved the operation to another nearby site and constructed a much more substantial post, eventually surrounding it with sun-dried adobe brick.

Wyeth and his operation, meanwhile, lasted only until 1837, when he sold Fort Hall and a second trading post he had built on the Columbia, to the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The US settled the boundary dispute with the British in 1846, establishing the border we know today between Washington and Canada. That opened up a torrent of settlers headed west into Oregon Country. Both forts became important replenishment points for emigrants. Fort Boise was famous for welcoming Oregon Trail travelers and providing them with needed provisions.

Fort Boise, the trading post near present day Parma, fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles. The original Fort Hall fell to a flood in 1863. A nearby replacement served emigrants for a few more years.

So, both forts, Hall and Boise, operated from about 1834, mostly as trading posts from about their original locations. Then it got confusing.

The military established the new Fort Boise in 1863 along the foothills north of the Boise River. The town of Boise sprung up below the fort.

In 1870, the US Army established a military post near the Blackfoot River about 25 miles from old Fort Hall. Rather than name the new post after some forgotten general, they called that one Fort Hall, too. In order to completely perplex students of history, the main town on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation also became Fort Hall. Then, to better tell the story of Fort Hall, history enthusiasts built a faithful replica of old Fort Hall near the zoo in Pocatello.

So, if someone mentions Fort Hall, ask them which one they’re referencing. Do they mean the reservation, the town, the old fort, the military fort, or the replica?

For Fort Boise, you only have to ask whether they mean the military fort or the trading post. Or, I suppose, the replica, which lurks near the trading post’s original location in Parma.

This 1849 lithograph shows Fort Boise, the trading post near Parma, in its prime. It fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles.

This 1849 lithograph shows Fort Boise, the trading post near Parma, in its prime. It fell into disuse in 1853 after flooding and Indian troubles.

Published on October 27, 2021 04:00

October 26, 2021

Challis Hot Springs (Tap to Read)

Robert Currie Beardsley, born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1840, had tried his luck at running a sawmill in Montana and mining in California, but he didn’t make a real go of it until he moved to Idaho in 1877. He and two partners, W. A. Norton and J.B. Hood discovered what would become the Beardsley Mine near Bayhorse. The town was so named because an earlier miner who had a couple of bay horses first told of of riches along what would soon become Bayhorse Creek, about 14 miles southwest of Challis.

The Beardsley Mine, once said to be the second largest silver mine in the state, was one of two major operations at Bayhorse. The other was the Ramshorn Mine.

After operating his mine for several years, Robert Beardsley sold his share in the mine for $40,000, setting him up for life. Sadly, it was a short life.

In 1884, Beardsley travelled to New Orleans for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. It was one of the first major world expositions. Think of it as a world’s fair. Beardsley probably did not go seeking a wife. Nevertheless, he found one.

The New Orleans Times-Democrat reported that on the 18th of February 1886, “another link was forged in the chain that binds Louisiana to the far Northwest. It was a golden link, and took the shape of a marriage between Robert Beardsley, one of the representative men of Idaho Territory—a hard-headed, successful miner—and Miss (Eleanor) Nellie Hallaran, of Magazine street, a native of this city. Mr. Beardsley met the lady last year while here on a visit to the Exposition. He said nothing but bore away in his Northwestern heart so strong an impress of her image that his return was a matter of necessity.” The newlyweds left the next day, taking a train to Blackfoot, then travelling by stage to Challis.

Though his name is attached to his mine in the history books, Beardsley left a legacy that far outlasted it. He homesteaded on a property east of Challis in 1880. The view was gorgeous and the meadows green, but it was the water that attracted Beardsley. It was hot. So hot that horse teams pulling Fresno scrapers to dig the soaking pools had to be changed out every couple of hours to let their hooves cool down.

Known today as Challis Hot Springs, the place was originally the Beardsley Resort and Hotel. Robert Beardsley floated logs down the Salmon from forested hillsides upriver and pulled them out on his property to construct some early buildings. Perhaps this casual, friendly relationship with the river gave him a false sense of confidence.

On June 30, 1888, Beardsley set out to cross the river to his hot springs resort with a team of horses and a wagon. While a handful of people watched, the raging current caught and tumbled the wagon, pulling the team and Beardsley under. Beardsley was sighted for a time in the current, but there was no way to attempt a rescue. You can find his grave on the mountainside above the hot springs today.

Eleanor eventually remarried a man named John Kirk. Eleanor continued to build up the hot springs resort. Ownership eventually passed to Eleanor and Robert Beardsley’s daughter Isabella and her husband John Hammond in 1931. Their son Robert Beardsley Hammond took over the hot springs in 1951. Twenty years later, his son, Robert Charles Hammond, purchased Challis Hot Springs. Bob and his wife Lorna maintained a home on the property until November 2013, when Bob passed away. Their two daughters, Kate Taylor and Mary Elizabeth Conner, manage the now fifth-generation facility today. Robert Currie Beardsley

Robert Currie Beardsley

The Beardsley Mine, once said to be the second largest silver mine in the state, was one of two major operations at Bayhorse. The other was the Ramshorn Mine.

After operating his mine for several years, Robert Beardsley sold his share in the mine for $40,000, setting him up for life. Sadly, it was a short life.

In 1884, Beardsley travelled to New Orleans for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. It was one of the first major world expositions. Think of it as a world’s fair. Beardsley probably did not go seeking a wife. Nevertheless, he found one.

The New Orleans Times-Democrat reported that on the 18th of February 1886, “another link was forged in the chain that binds Louisiana to the far Northwest. It was a golden link, and took the shape of a marriage between Robert Beardsley, one of the representative men of Idaho Territory—a hard-headed, successful miner—and Miss (Eleanor) Nellie Hallaran, of Magazine street, a native of this city. Mr. Beardsley met the lady last year while here on a visit to the Exposition. He said nothing but bore away in his Northwestern heart so strong an impress of her image that his return was a matter of necessity.” The newlyweds left the next day, taking a train to Blackfoot, then travelling by stage to Challis.

Though his name is attached to his mine in the history books, Beardsley left a legacy that far outlasted it. He homesteaded on a property east of Challis in 1880. The view was gorgeous and the meadows green, but it was the water that attracted Beardsley. It was hot. So hot that horse teams pulling Fresno scrapers to dig the soaking pools had to be changed out every couple of hours to let their hooves cool down.

Known today as Challis Hot Springs, the place was originally the Beardsley Resort and Hotel. Robert Beardsley floated logs down the Salmon from forested hillsides upriver and pulled them out on his property to construct some early buildings. Perhaps this casual, friendly relationship with the river gave him a false sense of confidence.

On June 30, 1888, Beardsley set out to cross the river to his hot springs resort with a team of horses and a wagon. While a handful of people watched, the raging current caught and tumbled the wagon, pulling the team and Beardsley under. Beardsley was sighted for a time in the current, but there was no way to attempt a rescue. You can find his grave on the mountainside above the hot springs today.

Eleanor eventually remarried a man named John Kirk. Eleanor continued to build up the hot springs resort. Ownership eventually passed to Eleanor and Robert Beardsley’s daughter Isabella and her husband John Hammond in 1931. Their son Robert Beardsley Hammond took over the hot springs in 1951. Twenty years later, his son, Robert Charles Hammond, purchased Challis Hot Springs. Bob and his wife Lorna maintained a home on the property until November 2013, when Bob passed away. Their two daughters, Kate Taylor and Mary Elizabeth Conner, manage the now fifth-generation facility today.

Robert Currie Beardsley

Robert Currie Beardsley

Published on October 26, 2021 04:00

October 25, 2021

"Buck" Buckner (Tap to Read)

In 1944 a freshman name Aurelius Buckner signed up to play football for Boise Junior College. Friends called the Boise native “Buck.” No one was surprised that Buck wanted to play football at BJC. He had lettered in football, basketball, and baseball at Boise High School.

Buckner also joined the BJC basketball team, and come spring of ’45, he joined the baseball team. Which Makes Aurelius Buckner the first black player in each sport in the Boise college’s history. In both basketball seasons he played (BJC was a two-year school, thus the Junior in its name) Buckner was the team captain and led the hoopsters in scoring.

In September of 1950, Buckner married another BJC grad, Dorothy Johnson. He would go on to be an honored sports referee, and a member of the Idaho Human Rights Commission, who would try his hand at politics in 1971, running unsuccessfully for a seat on the Boise City Council. Dorothy Buckner was always active in community affairs, serving multiple times on the Idaho NAACP board. She became a designee in the NAACP Heritage Hall of Fame in 2003. Both of the Buckners passed away in 2003. Their daughter, Cherie Buckner-Webb became Idaho’s first African-American legislator when she was elected to represent District 19 in the Idaho House in 2010. She was elected to the Idaho Senate in 2012 and served there until retiring in 2020.

Buckner also joined the BJC basketball team, and come spring of ’45, he joined the baseball team. Which Makes Aurelius Buckner the first black player in each sport in the Boise college’s history. In both basketball seasons he played (BJC was a two-year school, thus the Junior in its name) Buckner was the team captain and led the hoopsters in scoring.

In September of 1950, Buckner married another BJC grad, Dorothy Johnson. He would go on to be an honored sports referee, and a member of the Idaho Human Rights Commission, who would try his hand at politics in 1971, running unsuccessfully for a seat on the Boise City Council. Dorothy Buckner was always active in community affairs, serving multiple times on the Idaho NAACP board. She became a designee in the NAACP Heritage Hall of Fame in 2003. Both of the Buckners passed away in 2003. Their daughter, Cherie Buckner-Webb became Idaho’s first African-American legislator when she was elected to represent District 19 in the Idaho House in 2010. She was elected to the Idaho Senate in 2012 and served there until retiring in 2020.

Published on October 25, 2021 04:00

October 24, 2021

UXB Boise (Tap to Read)

The purpose of a fuse in the placement of dynamite is to give the person lighting the charge time to get away. Typically, that time is measured in seconds, not years.

While building a road along the bank of the New York Canal in 1900, the crew doing the dirt work found a fuse. Digging a little more carefully, they found the fuse was attached to a charge of dynamite. Rather than move what might be an unstable explosive, they chose to light the fuse and light out of there. The dynamite went off, just as whoever had set the charge ten years earlier had intended.

Speculation was that the lost explosive had been put in place while another crew was digging the New York Canal in 1890. Maybe they stopped for lunch, or they went home at the end of the day forgetting about that particular charge, which was planted near the Foote House just below where Lucky Peak Dam is today. Whoever placed the dynamite and inserted the fuse probably never thought it would have a ten-year delay.

While building a road along the bank of the New York Canal in 1900, the crew doing the dirt work found a fuse. Digging a little more carefully, they found the fuse was attached to a charge of dynamite. Rather than move what might be an unstable explosive, they chose to light the fuse and light out of there. The dynamite went off, just as whoever had set the charge ten years earlier had intended.

Speculation was that the lost explosive had been put in place while another crew was digging the New York Canal in 1890. Maybe they stopped for lunch, or they went home at the end of the day forgetting about that particular charge, which was planted near the Foote House just below where Lucky Peak Dam is today. Whoever placed the dynamite and inserted the fuse probably never thought it would have a ten-year delay.

Published on October 24, 2021 04:00

October 23, 2021

On Location in Idaho (Tap to Read)

In spite of the grand scenery, few movies have been shot in Idaho. That’s largely for logistical reasons, i.e., lack of motels in remote regions, lack of local production talent, lack of roads, etc.

Here are some movies that were shot in Idaho or had scenes in Idaho. Note that the links lead to an Amazon page about each movie. I get a few pennies if you buy something from Amazon after following that link. I don’t care if you buy anything, Amazon just wants you to know.

1923, The Grubstake, written and directed by Nell Shipman, she also starred in it. This and a series of short movies were shot at Priest Lake.

1931, Call of the Rockies, was partially filmed near Heise Hot Springs. It was also shown as All Faces West.

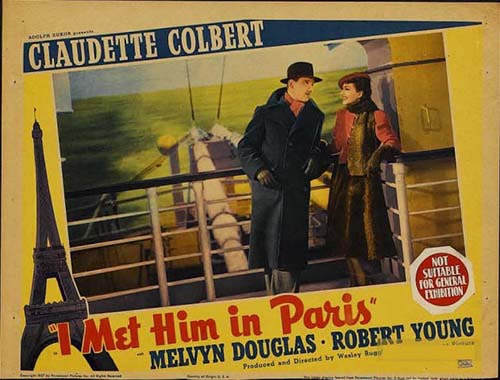

1936, I Met Him in Paris , starring Claudette Colbert, Melvyn Douglas, and Robert Young. Shot in Sun Valley, it was the first movie to take advantage of the new resort.

1936, Come and Get It, starring Edward Arnold, Joel McCrea, Frances Farmer, and Walter Brennan. A logging film where some of the exterior scenes were shot along the Clearwater.

1940, Northwest Passage , Starring Spencer Tracy, Robert Young, Walter Brennan, and Ruth Hussey. Shot near McCall at what is today the North Beach Unit of Ponderosa State Park. See previous post about the movie.

1941, Sun Valley Serenade , starring Sonja Henie, John Payne, and Glenn Miller. Shot partially in Sun Valley, you can still see it showing there every day.

1947, The Unconquered , starring Gary Cooper, Ward bond, and Paulette Goddard. Set in the 1760s, Fremont County became Virginia and other East Coast locations in this Cecil B. DeMille movie, though most of the “outdoor” scenes were shot on a Hollywood sound stage.

1950, Duchess of Idaho , starring Esther Williams, Van Johnson, and John Lund. The romantic comedy was shot in Sun Valley, where Esther Williams trades her trademark swimsuit for a ski parka.

1953, How to Marry a Millionaire , starring Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable, and Lauren Bacall. Allegedly some scenes were shot in Idaho, though this is suspect. The movie largely takes place in New York City.

1955, Storm Fear , starring Cornel Wilde, Jean Wallace, and Dan Duryea was a crime noir filmed partly in Sun Valley.

1956, Bus Stop , starring Marilyn Monroe, Don Murray, and Arthur O’Connell. Some scenes were shot in Sun Valley and the Wood River Valley. The movie was a highly acclaimed drama in which Monroe sang “That Old Black Magic.”

1959, Last Clear Chance , starring no one, really. It was a film sponsored by Union Pacific Railroad to promote safety at railroad crossings. It’s of some interest because it was shot in Idaho and William Agee, 21 at the time, appeared in it. Agee was later the CEO of Boise Cascade, Bendix, and finally Morrison Knudsen at various times. Many blame him for the demise of MK.

1965, Ski Party , starring Fankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman was a sex comedy shot in and around Sun Valley. It is noted (?) for the music in the film, including Lesley Gore’s “Sunshine, Lollipops, and Rainbows,” James brown’s “I Got You (I Feel Good,” and a couple of songs sung by Avalon. It was the last in a series of teen films that included Beach Blanket Bingo.

1973, Idaho Transfer , starring some people you’ve never heard of and Keith Carradine. It was an apocalyptic science fiction film directed by Peter Fonda. Most of the film was shot at Craters of the Moon, with some scenes film at Bruneau Dunes State Park. One critic called it a “usless piece of drivel about an obnoxious group of teens.” (Jay Robert Nash, The Motion Picture Guide).

1975, Breakheart Pass , starring Charles Bronson, Richard Crenna, Jill Ireland, and Ben Johnson. Filmed in North Idaho around Pierce. Many of the Native American extras were Nez Perce from Lapwai. It was notable as the last movie for veteran stuntman Yakima Canutt.

1980, Bronco Billy , starring Clint Eastwood, Sondra Locke, and Scatman Crothers. Filmed in and around Boise, Eagle, and Meridian. A lot of local talent became extras in the movie.

1980, Heaven’s Gate , starring Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, John Hurt, Jeff Bridges, Willem Dafoe, Micky Rourke, Joseph Cotton, and others. Shot partly in Wallace, it is best known for being a big flop. It cost around $44 million and brought in less than $4 million at the box office. Subsequent re-edits have received some acclaim.

1985, Pale Rider , starring, directed, and produced by Clint Eastwood. It was shot mostly in the Boulder Mountains in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. It was the first big-budget western shot after Heaven’s Gate and its impact was about 180 degrees from that failure. It received critical acclaim and pulled in more than $41 million on a budget just shy of $7 million.

1988, Moving , starring Richard Pryor. The setting is Boise, but only a couple of shots were actually filmed there.

1990, Ghost Dad , directed by Sidney Poitier and starry Bill Cosby. It was a seriously unfunny film, according to reviews. Some scenes MAY have been shot in Idaho.

1991, Talent for the Game , starring Edward James Olmos and Lorraine Bracco, used Genesee as its backdrop, with some scenes shot in Kellogg. It went quickly to video.

1992, Dark Horse , starring Ed Begley Jr, Samantha Eggar, Ari Meyers, Mimi Rogers, and Tab Hunter. Hunter wrote the original story. David Hemmings directed the film, which was shot not far from his home in Sun Valley.

1992, Toys , starring Robin Williams, Michael Gambon, Joan Cusack, Robin Wright, and LL Cool J. Directed by Barry Levinson, much of it was filmed in and around Moscow. Levinson was nominated for a Razzie for the film. Un, not an honor.

1997, Dante’s Peak , starring Pierce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton. Wallace became a town covered in ash for this (putting on my reviewer hat, now) ridiculous movie. It did well financially in spite of mostly negative reviews.

1998, Smoke Signals , starring Irene Bedard, Adam Bent, and Evan Adams. Shot on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation around Worley and Plummer and based on a short story by Sherman Alexie. It was an all native production that won numerous awards.

1998, Breakfast of Champions, starring Bruce Willis, Albert Finney, Nick Nolte, Barbara Hershey, and Lucas Haas. Based loosely on the Kurt Vonnegut novel of the same name it was shot in and around Twin Falls. It was a box office bomb that was widely panned by critics.

1999, Wild Wild West , starring Will Smith and Kevin Kline. This steampunk western comedy was loosely a take-off from the 1960s TV series of the same name. Some of the train exteriors were filmed on the old Camas Prairie Railroad, which has an abundance of dramatic trestles.

2001, Town and Country , starring Warren Beatty, Diane Keaton, Goldie Hawn, Gary Shandling, Andie MacDowell, Nastassja Kinski, and Charlton Heston. In spite of its stellar cast and a rewrite by Buck Henry, this one was a legendary flop, costing more than $100 million to make and bringing in just over $10 million. It was shot partially in Sun Valley.

2003, Shredder , starring Scott Weinger and Lindsey McKeon was a slasher film sohot at Silver Mounta Ski Resort, Kellogg.

2004, Napoleon Dynamite , starring Jon Heder, Efren Ramirez, Aaron Ruell, Jon Gries, and Sandy Martin. Shot on a budget of about $400,000, this collaboration between BYU film students using mostly friends as actors earned about $45 million. Written by Preston natives Jared and Jerusha Hess, and directed by Jared, it remains a cult classic.

2012, The Mooring , starring Hallie Todd, and others. This was a straight to DVD movie that was shot in Northern Idaho and Eastern Washington. Lake Coeur d’Alene, Chatcolet Lake, and the St. Joe show up in the film, along with camping scenes from Rocky Point and Plummer point in Heyburn State Park.

And, what have I missed? Do you know of some scenes that were shot in Idaho, or maybe an entire movie? Send me details or comment.

I Met Him in Paris, of course, was filmed mostly in Idaho.

I Met Him in Paris, of course, was filmed mostly in Idaho.

Published on October 23, 2021 04:00

October 22, 2021

SPUD (Tap to Read)

If you live in Idaho, you really should know what a spud is, don’t you think? You may not have personally dug up a potato, but you’ve probably been the beneficiary of someone who has. Nowadays potatoes are usually wrenched from the ground by a mechanical digger and sent up a conveyor chain that bounces most of the dirt away, past some humans who handpick the clods and vines off the chain before the potatoes are tumbled into a truck. It wasn’t always so.

For centuries potatoes were excavated by hand using various implements, one of which was called a spud. It was typically a sharp, narrow-bladed tool something like a trowel. The name probably goes back as far back as the mid-1400s and may have come from the Latin “spad” or sword. Or, it might have come from the Dutch “spyd” which was a short dagger, or the Norse “spjot” which was a spear. Most sources pinpoint its entry into the printed English language to a reference in 1845 in New Zealand.

And now you know what a spud was. Why the word slipped over from the digging implement to the tuber it was digging is lost to history, but it’s not too startling that it did.

According to the website todayifoundout.com some have tried to attach the origin of the word to an acronym. SPUD was an acronym in England for the Society for the Prevention of an Unwholesome Diet, a 19th Century group that had ideas about what one should eat. Potatoes were on the Do Not Eat side of their ledger. It’s unlikely, though, because making words out of acronyms is a 20th Century phenomenon that came into vogue long after the members of SPUD had all been buried, probably with full-sized shovels. Even the word “acronym” wasn’t in use until 1943. We can all thank our lucky stars that it was invented, though, because government could not exist without them.

So “spud” probably wasn’t an acronym, originally. I bet we could do a backformation, though. What should it mean today? Super Potatoes Under Dirt? Society for the Promotion of Underused Dingbats? You tell me.

For centuries potatoes were excavated by hand using various implements, one of which was called a spud. It was typically a sharp, narrow-bladed tool something like a trowel. The name probably goes back as far back as the mid-1400s and may have come from the Latin “spad” or sword. Or, it might have come from the Dutch “spyd” which was a short dagger, or the Norse “spjot” which was a spear. Most sources pinpoint its entry into the printed English language to a reference in 1845 in New Zealand.

And now you know what a spud was. Why the word slipped over from the digging implement to the tuber it was digging is lost to history, but it’s not too startling that it did.

According to the website todayifoundout.com some have tried to attach the origin of the word to an acronym. SPUD was an acronym in England for the Society for the Prevention of an Unwholesome Diet, a 19th Century group that had ideas about what one should eat. Potatoes were on the Do Not Eat side of their ledger. It’s unlikely, though, because making words out of acronyms is a 20th Century phenomenon that came into vogue long after the members of SPUD had all been buried, probably with full-sized shovels. Even the word “acronym” wasn’t in use until 1943. We can all thank our lucky stars that it was invented, though, because government could not exist without them.

So “spud” probably wasn’t an acronym, originally. I bet we could do a backformation, though. What should it mean today? Super Potatoes Under Dirt? Society for the Promotion of Underused Dingbats? You tell me.

Published on October 22, 2021 04:00

September 29, 2021

Holdup at the Nat

It was approaching midnight on September 28, 1902. Natatorium manager Fred Peterson, bartender Nicholas Steinfeld, and four guests, Frank Bayhorse, W. Heuschkel, Ida Wells, and Julia Valverde, were in the lounge at the Nat having a quiet chat. That’s when two rough looking men, their faces obscured by handkerchiefs, burst through the swinging doors pointing revolvers and telling everyone to line up against a wall.

While one of the robbers moved the customers and bartender into the hallway and held them at gunpoint, the other herded Peterson into the manager’s office and demanded that he open the safe. Peterson fumbled with the dial, his hands shaking.

The man pointing the gun at him said, “Hurry up or I will use my gun; we haven’t much time.”

Peterson might have wondered what the hurry was. After a few more seconds of twisting the dial he did it right and the door to the safe swung open.

The hold-up man ordered Peterson to take out the two money drawers and take them to the front of the Natatorium where everyone else was lined up under guard. Thug number two had relieved them all of their cash. The robbers ordered everyone to face the wall and stay there for ten minutes.

On their way out of the building the armed men encountered two customers coming through the door. They ordered them to get quickly inside and up against the wall. One, Si Kent, apparently did not comply fast enough. One of the thugs hit him on the head with the butt of his gun, stunning him.

The gunmen then ran to catch the trolley, which had just made its regular stop near the Nat, thus explaining the particular hurry they were in. The men ordered motorman Herbert Shaw at the point of a pistol to move it along and quickly. At Second Street they had him stop the trolley. They jumped off and headed north on foot.

Within the hour bloodhounds from the nearby penitentiary were called into service to find the hoodlums. It was to no avail.

Speculation was that the men knew the safe would have more money than usual, Friday being payday for many. They got away with more than $500 in cash, the equivalent of about $13,000 in today’s dollars.

A couple of days after the robbery, The Idaho Statesman speculated that motorman Shaw must “have broken all records, not only for the trip to Second Street, where the men alighted, but the entire distance to the power house. It was probable if ever he feared for his trolley to leave the wire it was during his enforced run that night.”

The robbery was said to be “undoubtedly one of the boldest holdups in the history of Boise.” Bold it was, and successful. The robbers were never caught.

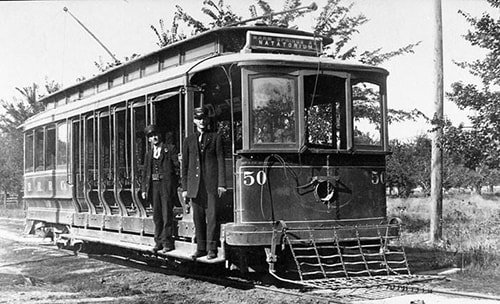

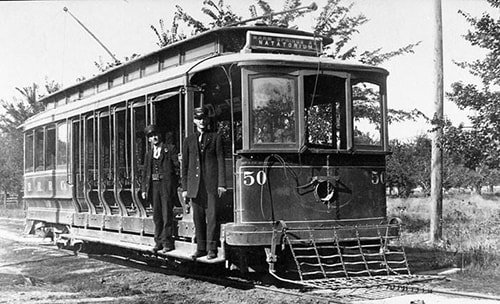

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

While one of the robbers moved the customers and bartender into the hallway and held them at gunpoint, the other herded Peterson into the manager’s office and demanded that he open the safe. Peterson fumbled with the dial, his hands shaking.

The man pointing the gun at him said, “Hurry up or I will use my gun; we haven’t much time.”

Peterson might have wondered what the hurry was. After a few more seconds of twisting the dial he did it right and the door to the safe swung open.

The hold-up man ordered Peterson to take out the two money drawers and take them to the front of the Natatorium where everyone else was lined up under guard. Thug number two had relieved them all of their cash. The robbers ordered everyone to face the wall and stay there for ten minutes.

On their way out of the building the armed men encountered two customers coming through the door. They ordered them to get quickly inside and up against the wall. One, Si Kent, apparently did not comply fast enough. One of the thugs hit him on the head with the butt of his gun, stunning him.

The gunmen then ran to catch the trolley, which had just made its regular stop near the Nat, thus explaining the particular hurry they were in. The men ordered motorman Herbert Shaw at the point of a pistol to move it along and quickly. At Second Street they had him stop the trolley. They jumped off and headed north on foot.

Within the hour bloodhounds from the nearby penitentiary were called into service to find the hoodlums. It was to no avail.

Speculation was that the men knew the safe would have more money than usual, Friday being payday for many. They got away with more than $500 in cash, the equivalent of about $13,000 in today’s dollars.

A couple of days after the robbery, The Idaho Statesman speculated that motorman Shaw must “have broken all records, not only for the trip to Second Street, where the men alighted, but the entire distance to the power house. It was probable if ever he feared for his trolley to leave the wire it was during his enforced run that night.”

The robbery was said to be “undoubtedly one of the boldest holdups in the history of Boise.” Bold it was, and successful. The robbers were never caught.

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

This might have been the getaway trolley used during the robbery of the Nat. Note the destination sign on this Warm Springs car.

Published on September 29, 2021 04:00

September 28, 2021

The Snake River's Lost Falls

Shoshone Falls, though largely captured for most of the year to run turbines for power generation, does sometimes run wild in the spring, giving us a taste of what it once looked like. We can see the free-falling water at Mesa Falls anytime, since it is the last large, unfettered falls on the Snake River.

Did you ever wonder what American Falls looked like prior to the building of the dam?

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.

The sketch shows a dramatic drop of water, split by a rock island. But one must take the accuracy with a grain of salt. As stated in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950 ,* by Sandy Harthorn and Kathleen Bettis, “Because Preuss was trained as a cartographer and not an artist, we can accept that his rather naïve drawings outline the land features rather than describe them as solid forms. Drawn in a stiff awkward manner, this deep vista appears exaggerated and fanciful. The river drops from a flattened plain over the edge of an angulated precipice more illusory than real.”

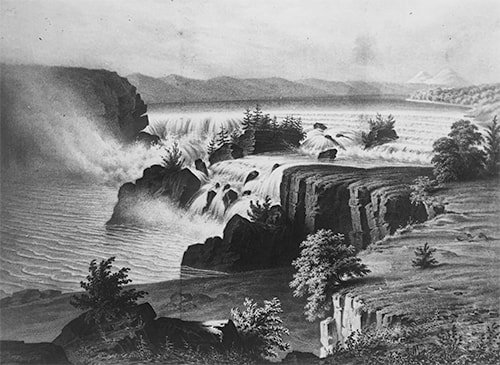

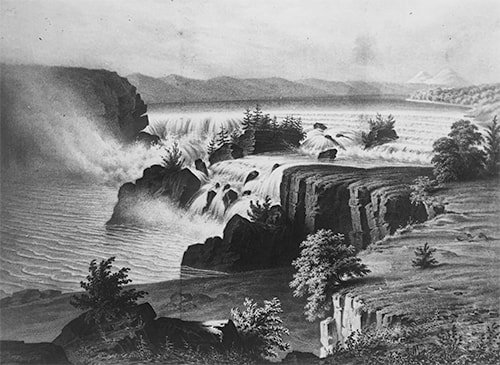

A second, more detailed lithograph was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.

A second, more detailed lithograph was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.

Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Did you ever wonder what American Falls looked like prior to the building of the dam?

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.

The earliest depiction of the falls that I’m aware of is a lithograph of the American Falls from a sketch by Charles Preuss. It appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of anything in what is now Eastern Idaho.The sketch shows a dramatic drop of water, split by a rock island. But one must take the accuracy with a grain of salt. As stated in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950 ,* by Sandy Harthorn and Kathleen Bettis, “Because Preuss was trained as a cartographer and not an artist, we can accept that his rather naïve drawings outline the land features rather than describe them as solid forms. Drawn in a stiff awkward manner, this deep vista appears exaggerated and fanciful. The river drops from a flattened plain over the edge of an angulated precipice more illusory than real.”

A second, more detailed lithograph was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it.

A second, more detailed lithograph was published in 1848. Though still depicting mountains in the background that are a little fanciful It shows a waterfall you’d certainly want to portage, unless you’re one of the kayakers who relishes a first drop. It looks about as daunting as Lower Mesa Falls, which kayakers occasionally run and live to tell about it. Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Finally, here’s a photo from the early 1900s, well before the dam went in (1925). The locomotive steaming across the trestle is on the Oregon Shortline tracks, westbound.

Published on September 28, 2021 04:00

September 27, 2021

The Man Who Created Idaho

I love odd little connections. Idaho has a ton of them with Abraham Lincoln. So many that they have become an obsession with Lincoln scholar and former Idaho Attorney General David Leroy.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck. One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

Leroy has spent a lifetime collecting Lincoln memorabilia and documenting his connections with Idaho. The most visible result of his passion is the exhibit Abraham Lincoln, His Legacy in Idaho at the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. Donated by David and Nancy Leroy in 2010, the exceptional exhibit displays more than 200 documents and artifacts.

So, what are the connections? Lincoln personally lobbied Congress for the creation of Idaho Territory, and signed that creation into law on March 3, 1863. But his interest in what would become our state started much earlier. Lincoln sought to be Idaho’s governor. Well, not exactly, but he did seek to govern Oregon Territory in 1849, part of which would one day become Idaho.

Lincoln was there at a meeting where it was decided the name of the new territory would be Idaho.

Many of the Lincoln connections were by way of Illinois and Indiana. Friends and neighbors of his helped shape the state. Samuel C. Parks, a law partner, was the territory’s first associate Supreme Court Justice. Another friend was Idaho’s seventh territorial governor, Mason Brayman. Lincoln’s bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, sought appointment as a territorial governor of Idaho from Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, but did not get it.

Years after Lincoln’s death a childhood playmate of Lincoln’s sons became U.S. Marshall of Idaho Territory, then a territorial congressional delegate. Fred T. Dubois lobbied hard to create the State of Idaho and to keep it from being split off and claimed by its neighbors.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, April 14, 1865, he had a meeting with Idaho’s delegate, William H. Wallace, about filling an Idaho supreme court vacancy. Wallace was said to have been invited to see a play that night with the Lincolns. He declined.

There’s a terrific little book about Lincoln’s connections to Idaho called Lincoln Never Slept Here, Idaho’s Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Tour written by Todd Shallat, PhD with Kathleen Craven Tuck.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

One of Boise’s statues of Abraham Lincoln (right) is located in a small park in front of Idaho’s statehouse. It is the oldest public statue of the 16th president in the western United States. The other, much larger statue, is a seated Lincoln in Julia Davis Park.

Published on September 27, 2021 04:00