Rick Just's Blog, page 109

November 29, 2021

Where the River Runs Dry

The Snake River Basin Adjudication (SRBA) was an administrative and legal process that began in 1987 to determine the water rights in the Snake River Basin drainage. The best history of that battle can be found in the book A Little Dam Problem, by Jim Jones, who as a water attorney, Idaho Attorney General, and finally an Idaho Supreme Court Justice, was in it to the top of his chest waders. The Final Unified Decree for the SRBA was signed on August 25, 2014, bringing a measure of certainty to holders of Idaho water rights. I’d love to sum it up in a couple of paragraphs, but the story is too complex for this format. I recommend Jim’s 374-page book as the ultimate summation.

What I can do is give you a little peek at an early indicator that there was trouble with Idaho’s system of allocating water.

It startled me to see an article in the August 11, 1905, Idaho Republican, one of the Blackfoot Newspapers at the time. The startling headline was “Snake River Goes Dry.” Was it on the front page in a shouting font stretching all the way across beneath the banner? No, it was on page five. The headline was the same size as the body copy, albeit in bold face.

It seems that upstream canals—one of the largest of which had been built by my great grandfather—had taken every drop of water to irrigate thirsty crops in the Upper Snake River Valley. Fortunately, there was a solution at hand. The article said, “The court having issued an order to close the headgates of certain canals having later rights, the county commissioners are making diversion of the water from the canals into the river, and it is expected that it will again flow down and supply the old canals in this locality within a few days.”

Imagine the mighty Snake River so drained of its water there were only puddles for splashing fish to try to survive in. If you’ve ever seen the torrent of water coming over Shoshone Falls in a wet spring, that probably seems all but impossible. Now, imagine that happening every year below Milner Dam. You don’t have to imagine it. You can go see the dry riverbed right below the dam during the irrigation season in all but the very wettest years. It doesn’t remain dry for long. The springs below Milner begin recharging the river almost immediately.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

What I can do is give you a little peek at an early indicator that there was trouble with Idaho’s system of allocating water.

It startled me to see an article in the August 11, 1905, Idaho Republican, one of the Blackfoot Newspapers at the time. The startling headline was “Snake River Goes Dry.” Was it on the front page in a shouting font stretching all the way across beneath the banner? No, it was on page five. The headline was the same size as the body copy, albeit in bold face.

It seems that upstream canals—one of the largest of which had been built by my great grandfather—had taken every drop of water to irrigate thirsty crops in the Upper Snake River Valley. Fortunately, there was a solution at hand. The article said, “The court having issued an order to close the headgates of certain canals having later rights, the county commissioners are making diversion of the water from the canals into the river, and it is expected that it will again flow down and supply the old canals in this locality within a few days.”

Imagine the mighty Snake River so drained of its water there were only puddles for splashing fish to try to survive in. If you’ve ever seen the torrent of water coming over Shoshone Falls in a wet spring, that probably seems all but impossible. Now, imagine that happening every year below Milner Dam. You don’t have to imagine it. You can go see the dry riverbed right below the dam during the irrigation season in all but the very wettest years. It doesn’t remain dry for long. The springs below Milner begin recharging the river almost immediately.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

In this Google Earth satellite photo you can see the dry Snake River below the Milner Dam, with all the water diverted into canals to the north.

Published on November 29, 2021 05:13

November 28, 2021

WPA Canning (Tap to read the story)

I continue to be amazed at the way this country pulled together during the Great Depression. Much of that came about through the efforts of the Works Projects Administration (WPA). The WPA programs started in 1935 and went into the war years, ending in 1943. Many of the projects were on a large scale such as the building of roads and parks. I recently ran across a program that was new to me.

The Canning Program was instituted to feed needy school children and persons in public institutions. Much of the produce came from the related Gardening Program.

Children signed up for “Rustler Clubs,” going out in groups to pick surplus fruits and vegetables.

Idaho had one of the larger canning projects. In July, 1936, production in Idaho reached 18,672 cans of vegetables, fruits, jellies, jams, and soups. During its lifetime, the program canned 85,000,000 quarts of food nationwide.

As the war came along the focus of the Boise canning program changed. It became a community canning service for families who wanted to preserve food so they could save their ration stamps. Operating out of the Ada County Fairgrounds, the Boise-Meridian cannery assisted women in putting up their own produce.

A 1945 Statesman article listed asparagus, peas, Swiss chard, carrots and peas in combination, chicken, and pork and beans as food being canned under expert supervision.

The Canning Program was instituted to feed needy school children and persons in public institutions. Much of the produce came from the related Gardening Program.

Children signed up for “Rustler Clubs,” going out in groups to pick surplus fruits and vegetables.

Idaho had one of the larger canning projects. In July, 1936, production in Idaho reached 18,672 cans of vegetables, fruits, jellies, jams, and soups. During its lifetime, the program canned 85,000,000 quarts of food nationwide.

As the war came along the focus of the Boise canning program changed. It became a community canning service for families who wanted to preserve food so they could save their ration stamps. Operating out of the Ada County Fairgrounds, the Boise-Meridian cannery assisted women in putting up their own produce.

A 1945 Statesman article listed asparagus, peas, Swiss chard, carrots and peas in combination, chicken, and pork and beans as food being canned under expert supervision.

Published on November 28, 2021 04:00

November 27, 2021

Scissors Grinders (Tap to read the story)

Knives and scissors of high-quality steel tend to keep their edge for a long time. If they get dull, we sometimes toss them away today, or make a stab (sorry) at sharpening them ourselves.

In days gone by traveling professionals called scissors grinders would visit a community or farm and offer to sharpen instruments that were often not of the best quality.

In the November 16, 1886 edition of the Idaho Statesman, a short article described the profession thus:

“Most of the grinders leave town in the summer time. They commence about the first of May, and you don’t often see one carrying his machine around the city after the 1st of June. They go into the country and work in the little towns and among the farmers sharpening scissors and razors. Once in a while a $2 or $3 job is picked up in one house putting shaving tools in order and fixing the scissors.”

The chance to earn money wasn’t the only reason the grinders headed to the country in the summer.

“It don’t take much bread and meat to get along on when watermelons, cantaloupe and fruit are plenty. Potato patches and roasting ears help out a good deal, and occasionally a hen’s nest is found in some fence corner, so you see if a fellow wants to, he can live very cheap and save the money he earns.”

Grinders apparently saved up in the summer, because one needed cash to live through a winter in the city.

There was another mention of a scissors grinder in the April 18, 1891 Statesman. “A scissors grinder attracted considerable attention on the street. He was the first who has been in town for a long time.”

Scissors grinders were included in a full-page story in 1909 when the banner headline in the Statesman read, “Humble Yet Remunerative Occupations in Boise.” Other humble jobs included stove doctor, lawn surgeon, and postcard vendor. The scissor grinder interviewed for the story said he bought his grinder for $250 and could make $3-$7 a day.

Not a fortune, maybe, but one could still put some money away. In the February 21, 1905 edition of the Mountain Home Republican, this little quip appeared: “John J. Dowd, a scissors grinder, died, leaving a fortune of $30,000. John was a sharp businessman.”

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

In days gone by traveling professionals called scissors grinders would visit a community or farm and offer to sharpen instruments that were often not of the best quality.

In the November 16, 1886 edition of the Idaho Statesman, a short article described the profession thus:

“Most of the grinders leave town in the summer time. They commence about the first of May, and you don’t often see one carrying his machine around the city after the 1st of June. They go into the country and work in the little towns and among the farmers sharpening scissors and razors. Once in a while a $2 or $3 job is picked up in one house putting shaving tools in order and fixing the scissors.”

The chance to earn money wasn’t the only reason the grinders headed to the country in the summer.

“It don’t take much bread and meat to get along on when watermelons, cantaloupe and fruit are plenty. Potato patches and roasting ears help out a good deal, and occasionally a hen’s nest is found in some fence corner, so you see if a fellow wants to, he can live very cheap and save the money he earns.”

Grinders apparently saved up in the summer, because one needed cash to live through a winter in the city.

There was another mention of a scissors grinder in the April 18, 1891 Statesman. “A scissors grinder attracted considerable attention on the street. He was the first who has been in town for a long time.”

Scissors grinders were included in a full-page story in 1909 when the banner headline in the Statesman read, “Humble Yet Remunerative Occupations in Boise.” Other humble jobs included stove doctor, lawn surgeon, and postcard vendor. The scissor grinder interviewed for the story said he bought his grinder for $250 and could make $3-$7 a day.

Not a fortune, maybe, but one could still put some money away. In the February 21, 1905 edition of the Mountain Home Republican, this little quip appeared: “John J. Dowd, a scissors grinder, died, leaving a fortune of $30,000. John was a sharp businessman.”

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

Scissors grinder near Burley, Idaho, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, Russel Lee photographer.

Published on November 27, 2021 04:00

November 26, 2021

The Ramblin' Kid (Tap to read the story)

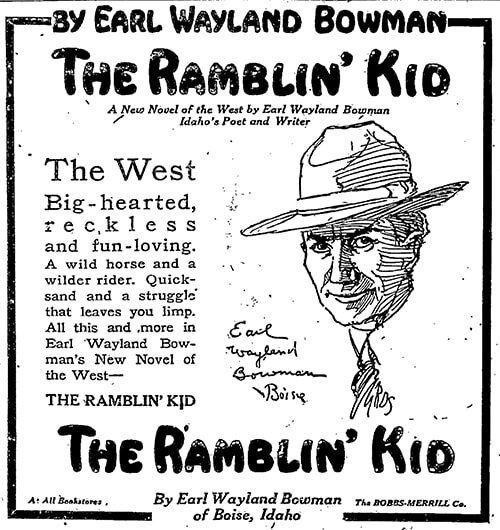

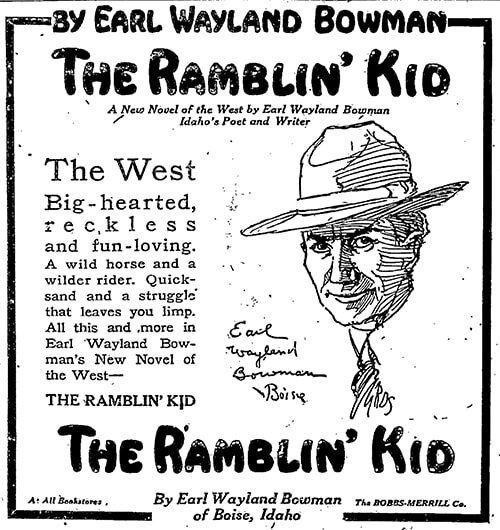

If you’ve been reading these posts for a while you might remember that Agnes Just Reid, my great aunt, corresponded with several Western writers in her day, including B.M. Bower and Frank Robertson. One of Bower’s books, Ranch of the Wolverine, was written while she was staying with Agnes.

The family has some correspondence and other clues and scraps about another writer she was friends with. He went by the nickname “The Ramblin’ Kid.” In his correspondence he would sometimes refer to Agnes as “The Range Cayuse,” after a book of poetry she wrote of the same name. The Ramblin’ Kid was a successful novel by the author, whose real name was Earl Wayland Bowman. I had done enough research to know that he wrote several books and some screenplays but I got distracted by some shiny object before I could dig up his Idaho connection.

Today, I did the requisite digging and found his Idaho roots run deep, though he was born in Missouri in 1875. Orphaned at about age 10, he spent many years knocking around Texas and the Southwest working any cowboy kind of job that came his way. This early experience would serve him well as a writer of the American West.

Somewhere along the line he learned how to set type and made his living as a traveling printer. It seemed only natural that he would come up with something to print.

He and his wife, Elva, moved to Idaho in 1901, living first in Weiser, then on a ranch he built up near Council. He began writing for a number of local papers, everything from letters to the editor to poetry. The latter was dense with a religious slant, but apparently popular with readers. He wrote poems regularly for the Idaho Statesman for several years.

Bowman started a periodical titled Homeseekers Monthly, essentially a real estate rag. It later morphed into a magazine called The Golden Trail. It featured short stories, poetry, and articles about Idaho written by Bowman and other writers. It was in The Golden Trail that he began developing his persona as “The Ramblin’ Kid.”

A frequent orator at political gatherings of the day, Bowman somehow got himself elected as an Idaho State Senator in 1914. I’m not the only one who finds this startling. “The Ramblin’ Kid” was a socialist and the only state senator of that persuasion ever elected in Idaho. He got several bills through the Legislature, including the Emergency Employment Act, which put the burden on counties to create jobs for everyone who needed one. Counties heartily resisted it. The Idaho Supreme Court found it unconstitutional 18 months later. Bowman lost the next election and went back to writing.

He passed away in southern California in 1952. His family donated Bowman’s papers to Boise State College in 1972.

Among those papers was a 1923 letter to Agnes Just Reid in which he groused about a letter he had received from the California State Librarian who wanted biographical information on him as a California author. He replied, the he was “an Idaho author if any kind,” and added to Agnes, “I’m all Idaho and want to stay that way.”

For more on Bowman, visit the Special Collections and Archives page on the Boise State University Library website, from which much of this information was gathered.

The family has some correspondence and other clues and scraps about another writer she was friends with. He went by the nickname “The Ramblin’ Kid.” In his correspondence he would sometimes refer to Agnes as “The Range Cayuse,” after a book of poetry she wrote of the same name. The Ramblin’ Kid was a successful novel by the author, whose real name was Earl Wayland Bowman. I had done enough research to know that he wrote several books and some screenplays but I got distracted by some shiny object before I could dig up his Idaho connection.

Today, I did the requisite digging and found his Idaho roots run deep, though he was born in Missouri in 1875. Orphaned at about age 10, he spent many years knocking around Texas and the Southwest working any cowboy kind of job that came his way. This early experience would serve him well as a writer of the American West.

Somewhere along the line he learned how to set type and made his living as a traveling printer. It seemed only natural that he would come up with something to print.

He and his wife, Elva, moved to Idaho in 1901, living first in Weiser, then on a ranch he built up near Council. He began writing for a number of local papers, everything from letters to the editor to poetry. The latter was dense with a religious slant, but apparently popular with readers. He wrote poems regularly for the Idaho Statesman for several years.

Bowman started a periodical titled Homeseekers Monthly, essentially a real estate rag. It later morphed into a magazine called The Golden Trail. It featured short stories, poetry, and articles about Idaho written by Bowman and other writers. It was in The Golden Trail that he began developing his persona as “The Ramblin’ Kid.”

A frequent orator at political gatherings of the day, Bowman somehow got himself elected as an Idaho State Senator in 1914. I’m not the only one who finds this startling. “The Ramblin’ Kid” was a socialist and the only state senator of that persuasion ever elected in Idaho. He got several bills through the Legislature, including the Emergency Employment Act, which put the burden on counties to create jobs for everyone who needed one. Counties heartily resisted it. The Idaho Supreme Court found it unconstitutional 18 months later. Bowman lost the next election and went back to writing.

He passed away in southern California in 1952. His family donated Bowman’s papers to Boise State College in 1972.

Among those papers was a 1923 letter to Agnes Just Reid in which he groused about a letter he had received from the California State Librarian who wanted biographical information on him as a California author. He replied, the he was “an Idaho author if any kind,” and added to Agnes, “I’m all Idaho and want to stay that way.”

For more on Bowman, visit the Special Collections and Archives page on the Boise State University Library website, from which much of this information was gathered.

Published on November 26, 2021 04:00

November 25, 2021

The Pocatello Ordinance Plant (Tap to read)

You’re probably aware that Idaho had a major military installation during World War II, the Farragut Naval Training Station. Fewer people know about another important Naval facility that was located in the state, the Naval Ordinance Plant in Pocatello.

I should clarify that the site is in Pocatello today. It was three miles north of Pocatello when it was built.

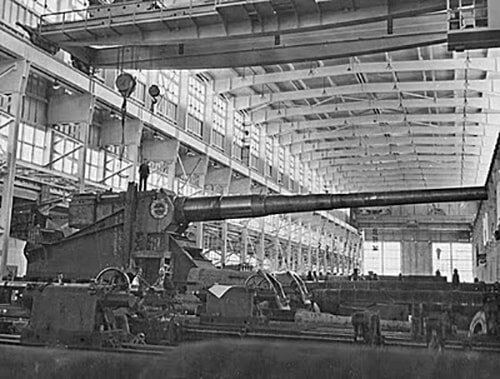

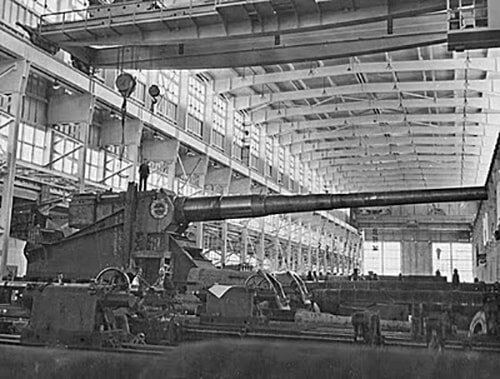

The Naval Ordnance Plant was commissioned in April 1942. It was a huge facility. The shop where the big 16” ship cannons were refurbished was 840 feet long and 352 feet wide. Eventually about 50 buildings were constructed on the site.

Manufacturing and refurbishing enormous guns for battleships was the main focus of the facility. Artillery needs to be refurbished after a certain number of shots are fired because the spiral grooves inside the barrel wear down. Those grooves set a projectile spinning, improving its steady trajectory.

The Pocatello plant was one of only two in the country to do this kind of work, and the only one west of the Mississippi. The site was chosen because Pocatello is far enough inland to make enemy bombardment less likely, and it was a major railroad and highway hub.

An ancillary part of the operation took place on the Arco Desert. About 50 miles northwest of Pocatello, the Navy picked a 271 square mile site from which they could test fire the big guns. It was called the Naval Proving Ground. The site contained some 27 buildings; shops, administrative operations, powder magazines, warehouses, and housing for personnel. During World War II the Navy fired most of the ordnance into the desert to the north. For a time, during the Vietnam Conflict, projectiles were aimed at the side of the Big Southern Butte. The change in targeting was due to development in the area of the original site.

The Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant was decommissioned in the 1950s and sold. The test site on the desert became a part of what is now called the Idaho National Laboratory. Ties to the Navy remained strong there over the years as nuclear sub crews got much of their training in the Idaho desert. The big gun shop at the Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant.

The big gun shop at the Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant.  Test firing a ship cannon at the Naval Proving Ground in the Arco Desert.

Test firing a ship cannon at the Naval Proving Ground in the Arco Desert.

I should clarify that the site is in Pocatello today. It was three miles north of Pocatello when it was built.

The Naval Ordnance Plant was commissioned in April 1942. It was a huge facility. The shop where the big 16” ship cannons were refurbished was 840 feet long and 352 feet wide. Eventually about 50 buildings were constructed on the site.

Manufacturing and refurbishing enormous guns for battleships was the main focus of the facility. Artillery needs to be refurbished after a certain number of shots are fired because the spiral grooves inside the barrel wear down. Those grooves set a projectile spinning, improving its steady trajectory.

The Pocatello plant was one of only two in the country to do this kind of work, and the only one west of the Mississippi. The site was chosen because Pocatello is far enough inland to make enemy bombardment less likely, and it was a major railroad and highway hub.

An ancillary part of the operation took place on the Arco Desert. About 50 miles northwest of Pocatello, the Navy picked a 271 square mile site from which they could test fire the big guns. It was called the Naval Proving Ground. The site contained some 27 buildings; shops, administrative operations, powder magazines, warehouses, and housing for personnel. During World War II the Navy fired most of the ordnance into the desert to the north. For a time, during the Vietnam Conflict, projectiles were aimed at the side of the Big Southern Butte. The change in targeting was due to development in the area of the original site.

The Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant was decommissioned in the 1950s and sold. The test site on the desert became a part of what is now called the Idaho National Laboratory. Ties to the Navy remained strong there over the years as nuclear sub crews got much of their training in the Idaho desert.

The big gun shop at the Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant.

The big gun shop at the Pocatello Naval Ordnance Plant.  Test firing a ship cannon at the Naval Proving Ground in the Arco Desert.

Test firing a ship cannon at the Naval Proving Ground in the Arco Desert.

Published on November 25, 2021 04:00

November 24, 2021

A Construction Boom in the Magic Valley (Tap to read the story)

The internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry during World War II was devastating for those who went through it. I understand that many people at the time thought it was a necessary move, and that our feelings about it today are filtered through the lens of hindsight. For those interned there is no question that it was terrible. Today, I want to write about one aspect of the program that is seldom discussed.

Construction of the Hunt Camp at Minidoka in the summer of 1942 was the Depression-ender for the Magic Valley. Masons, carpenters, and their helpers could earn $72 a week during construction. If they could find work at all during that time, $20 to $25 a week was the norm for those trades.

Morrison-Knudsen was the contractor at the camp. The payroll for the M-K workers rolled through the Magic Valley bringing the first taste of prosperity to bars, restaurants, and clothing stores they had experienced in years. People brought their rattle-trap cars in to trade up and made long-overdue improvements to their homes.

The workers often lived in shacks and used outhouses. They were heard to grumble about the lucky “Japs” for whom they were building communal kitchens, laundries and bathhouses—luxuries the workers didn’t enjoy. No doubt the families forced to move to the Idaho desert from Portland and Seattle considered none of it luxurious.

Much of the information contained in this post comes from History of Idaho, Volume2, Leonard J. Arrington, published by the University of Idaho Press and the Idaho State Historical Society in 1994.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

Construction of the Hunt Camp at Minidoka in the summer of 1942 was the Depression-ender for the Magic Valley. Masons, carpenters, and their helpers could earn $72 a week during construction. If they could find work at all during that time, $20 to $25 a week was the norm for those trades.

Morrison-Knudsen was the contractor at the camp. The payroll for the M-K workers rolled through the Magic Valley bringing the first taste of prosperity to bars, restaurants, and clothing stores they had experienced in years. People brought their rattle-trap cars in to trade up and made long-overdue improvements to their homes.

The workers often lived in shacks and used outhouses. They were heard to grumble about the lucky “Japs” for whom they were building communal kitchens, laundries and bathhouses—luxuries the workers didn’t enjoy. No doubt the families forced to move to the Idaho desert from Portland and Seattle considered none of it luxurious.

Much of the information contained in this post comes from History of Idaho, Volume2, Leonard J. Arrington, published by the University of Idaho Press and the Idaho State Historical Society in 1994.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

The Minidoka camp under construction.

Published on November 24, 2021 04:00

November 23, 2021

The Airman and the Headhunters (Tap to read the story)

You’ve seen the comic trope where a couple of people are tied up and sitting in a big iron pot over a fire, right? It’s the setup to a cannibal joke of some kind. To Boisean John Nelson, it wasn’t a joke.

T/Sgt Nelson, an aerial gunner, and six companions bailed out of their B-24 Liberator bomber in November 1944, parachuting into jungles of Borneo. They were found by natives who had been headhunters prior to getting a little religion from missionaries they had met. But it wasn’t the headhunters the men were worried about; it was the Japanese.

The Boise High grad was 19 when he found himself running from Japanese soldiers in Borneo. He and the other six who had parachuted from the plane joined up with five Navy fliers who had bailed out of their flaming plane. Five other Navy men had been found and killed by the Japanese.

The Americans were hustled from village to village trying to outrun the enemy. They were on the lam for eight months before they were finally rescued by Australian guerilla fighters.

Nelson had malaria four times during those months. He was finally cured of that when the natives fed him some medicine made from the bark of a tree.

The men subsisted mostly on rice with a little chicken and pork coming along occasionally. For entertainment, when they weren’t on the run, they read and re-read a few old copies of Readers Digest. In one village one of the Liberator engineers got an old phonograph working that had been left by Dutch traders. They had two records, “Star Dust,” and “Lullaby of Broadway.” Nelson, quoted in the September 7, 1945 Idaho Statesman, said, “I’ll never forget the taste of rice or the melodies of those two songs.”

The story of the men’s trial was told in the 2009 PBS documentary, The Airmen and the Headhunters. A transcript is available here, but the video itself was unavailable last time I checked.

John Nelson passed away in 2000 in Tucson, Arizona.

T/Sgt Nelson, an aerial gunner, and six companions bailed out of their B-24 Liberator bomber in November 1944, parachuting into jungles of Borneo. They were found by natives who had been headhunters prior to getting a little religion from missionaries they had met. But it wasn’t the headhunters the men were worried about; it was the Japanese.

The Boise High grad was 19 when he found himself running from Japanese soldiers in Borneo. He and the other six who had parachuted from the plane joined up with five Navy fliers who had bailed out of their flaming plane. Five other Navy men had been found and killed by the Japanese.

The Americans were hustled from village to village trying to outrun the enemy. They were on the lam for eight months before they were finally rescued by Australian guerilla fighters.

Nelson had malaria four times during those months. He was finally cured of that when the natives fed him some medicine made from the bark of a tree.

The men subsisted mostly on rice with a little chicken and pork coming along occasionally. For entertainment, when they weren’t on the run, they read and re-read a few old copies of Readers Digest. In one village one of the Liberator engineers got an old phonograph working that had been left by Dutch traders. They had two records, “Star Dust,” and “Lullaby of Broadway.” Nelson, quoted in the September 7, 1945 Idaho Statesman, said, “I’ll never forget the taste of rice or the melodies of those two songs.”

The story of the men’s trial was told in the 2009 PBS documentary, The Airmen and the Headhunters. A transcript is available here, but the video itself was unavailable last time I checked.

John Nelson passed away in 2000 in Tucson, Arizona.

Published on November 23, 2021 04:00

November 22, 2021

Idaho's First Sermon (Tap to read the story)

In Idaho history, 1834 is an important date. It was that year that both Fort Hall and Fort Boise, fur trading posts, were established.

Seventy-five years later on July 3 and 4, 1909, they were celebrating a Diamond Jubilee in Blackfoot. It wasn’t about either of the trading posts, exactly. It was in commemoration of the first Protestant service west of the Rocky Mountains being conducted in a grove near Fort Hall, and the first raising of the United State flag in the Pacific Northwest.

Jason Lee was a Canadian Methodist Episcopalian missionary who had travelled west with Nathaniel Wyeth, the man who founded Fort Hall. Wyeth was in the fur business. Lee wanted to save souls. He was on his way to establish a mission in the Willamette Valley.

On July 27, 1834, Rev. Lee preached his sermon in the grove, at the request of Wyeth. Gathered among the cottonwoods with the sound of the Snake River murmuring nearby, were an assortment of white and Indian trappers. Lee preached on the text: “whether, therefore, ye eat or drink, do all for the glory of god.”

Having been on their best behavior, those who attended the sermon decided to have a little fun afterwards by ginning up some horse races. A French-Canadian trapper named Kanseau fell from his horse during the race and was killed. Not long after Jason Lee had preached that first sermon, he found himself officiating at a funeral. The man was buried beneath a buffalo robe.

It was the sermon the citizens of Blackfoot were celebrating in 1909, and they did it up right, spending a little over $1,000 on the celebration. Idaho Governor James H. Brady gave the keynote speech, a rousing history of the sermon, adding, “to Idaho belongs the honor and distinction of the first flag of our country ever raised in this western land.”

The Village Improvement Society of Blackfoot presented the governor a US flag in honor of the event.

Byrd Trego, the colorful editor of the Idaho Republican in Blackfoot, wrote, “Blackfoot was the most-talked-of town in Idaho for a couple of weeks before the celebration, because of what Blackfoot was preparing to celebrate. It was the most-talked-of place for a couple of weeks afterwards because there was a grand discussion going on to see if what we claimed about early history was correct, and it was found to be substantially as advertised by the publicity men at Blackfoot.”

Jason Lee went on to Oregon after his sermon, and probably never came back to Idaho. His name lives on in Blackfoot, though, where the Jason Lee Memorial United Methodist Church is located.

A sketch of Jason Lee is inset in the lower left of this photograph of the area where his sermon took place. The photo is undated but likely took place around the time of the Diamond Jubilee held in nearby Blackfoot in 1909. Grove photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection. The Jason Lee image in the public domain.

A sketch of Jason Lee is inset in the lower left of this photograph of the area where his sermon took place. The photo is undated but likely took place around the time of the Diamond Jubilee held in nearby Blackfoot in 1909. Grove photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection. The Jason Lee image in the public domain.

Seventy-five years later on July 3 and 4, 1909, they were celebrating a Diamond Jubilee in Blackfoot. It wasn’t about either of the trading posts, exactly. It was in commemoration of the first Protestant service west of the Rocky Mountains being conducted in a grove near Fort Hall, and the first raising of the United State flag in the Pacific Northwest.

Jason Lee was a Canadian Methodist Episcopalian missionary who had travelled west with Nathaniel Wyeth, the man who founded Fort Hall. Wyeth was in the fur business. Lee wanted to save souls. He was on his way to establish a mission in the Willamette Valley.

On July 27, 1834, Rev. Lee preached his sermon in the grove, at the request of Wyeth. Gathered among the cottonwoods with the sound of the Snake River murmuring nearby, were an assortment of white and Indian trappers. Lee preached on the text: “whether, therefore, ye eat or drink, do all for the glory of god.”

Having been on their best behavior, those who attended the sermon decided to have a little fun afterwards by ginning up some horse races. A French-Canadian trapper named Kanseau fell from his horse during the race and was killed. Not long after Jason Lee had preached that first sermon, he found himself officiating at a funeral. The man was buried beneath a buffalo robe.

It was the sermon the citizens of Blackfoot were celebrating in 1909, and they did it up right, spending a little over $1,000 on the celebration. Idaho Governor James H. Brady gave the keynote speech, a rousing history of the sermon, adding, “to Idaho belongs the honor and distinction of the first flag of our country ever raised in this western land.”

The Village Improvement Society of Blackfoot presented the governor a US flag in honor of the event.

Byrd Trego, the colorful editor of the Idaho Republican in Blackfoot, wrote, “Blackfoot was the most-talked-of town in Idaho for a couple of weeks before the celebration, because of what Blackfoot was preparing to celebrate. It was the most-talked-of place for a couple of weeks afterwards because there was a grand discussion going on to see if what we claimed about early history was correct, and it was found to be substantially as advertised by the publicity men at Blackfoot.”

Jason Lee went on to Oregon after his sermon, and probably never came back to Idaho. His name lives on in Blackfoot, though, where the Jason Lee Memorial United Methodist Church is located.

A sketch of Jason Lee is inset in the lower left of this photograph of the area where his sermon took place. The photo is undated but likely took place around the time of the Diamond Jubilee held in nearby Blackfoot in 1909. Grove photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection. The Jason Lee image in the public domain.

A sketch of Jason Lee is inset in the lower left of this photograph of the area where his sermon took place. The photo is undated but likely took place around the time of the Diamond Jubilee held in nearby Blackfoot in 1909. Grove photo courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection. The Jason Lee image in the public domain.

Published on November 22, 2021 04:00

November 21, 2021

Hannifin's (Tap to read the story)

John Bernard Hannifin, born in Horseshoe Bend in 1893, first caught the attention of Boiseans in the Idaho Statesman in quite a dramatic way. The headline, on July 11, 1911, read “Fast Driving Probably Saved Young Man’s Life.”

It seems that Hannifin, 18 at the time, and some of his friends were in Lowman playing cards around a campfire, John got up to change places with one of the other men to “change his luck.” It did. His movement caused a Lugar automatic he was carrying to accidentally discharge, sending a bullet through his right thigh and into his left leg where it lodged in his calf muscle.

His friends drove Hannifin at a hard pace all night to Idaho City where they were met by a doctor from Boise. Dr. Tukey was quoted as saying the mad dash from Lowman, 52 miles away, saved Hannifin from septicemia.

The next mention was five years later. No violence was involved. This was a love story.

This time the headline announced, “Bride of Boise Man was Nurse in Scotland.” Bella Mumm lived in Greenock, Scotland where she volunteered as an assistant to Red Cross nurses treating the casualties of WWI. But the romance took place in Seattle, where she and John Hannifin met. She had been visiting her brother in Canada and made a short trip to Seattle. Why Hannifin was in Seattle was never stated. The important thing was that they fell in love and she came to Boise later to be his bride.

The third mention of Hannifin was in an ad for a cigar store in 1926. John Hannifin hadn’t been missing for 10 years, he just hadn’t made much news. He had been working at the Salmon Cigar Store “Kitty Corner from the Owyhee Hotel” since it opened in 1908. When Edmund Salmon died in 1922, Hannifin took over. It became a Boise institution, selling cigars, pipe tobacco, beer, soda, comic books, and “gentlemen’s magazines.” The Hannifin family owned the place until the late 1960s. The store retained the name until it finally closed in 2019. John Hannifin died at age 87 in 1980.

The building where Hannifins was housed is one of the oldest commercial buildings in Boise, constructed in 1897. It was originally part of the Beckworth Building, home to a grocer, a hardware store, and a clothing store. The building where Hannifin’s was located for all those years is one of several in the Lower Main Street Commercial Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, Hannifin’s looks much the same on the outside of the building. Ryan Salamon, the barber who renovated the building for his new shop, kept many historic touches including the cast iron stove in the middle of the building. The Hannifin’s sign once above the front door is now displayed inside of the Belmont Barber Shop.

Inside the barber shop where Hannifin's once was.

Inside the barber shop where Hannifin's once was.

It seems that Hannifin, 18 at the time, and some of his friends were in Lowman playing cards around a campfire, John got up to change places with one of the other men to “change his luck.” It did. His movement caused a Lugar automatic he was carrying to accidentally discharge, sending a bullet through his right thigh and into his left leg where it lodged in his calf muscle.

His friends drove Hannifin at a hard pace all night to Idaho City where they were met by a doctor from Boise. Dr. Tukey was quoted as saying the mad dash from Lowman, 52 miles away, saved Hannifin from septicemia.

The next mention was five years later. No violence was involved. This was a love story.

This time the headline announced, “Bride of Boise Man was Nurse in Scotland.” Bella Mumm lived in Greenock, Scotland where she volunteered as an assistant to Red Cross nurses treating the casualties of WWI. But the romance took place in Seattle, where she and John Hannifin met. She had been visiting her brother in Canada and made a short trip to Seattle. Why Hannifin was in Seattle was never stated. The important thing was that they fell in love and she came to Boise later to be his bride.

The third mention of Hannifin was in an ad for a cigar store in 1926. John Hannifin hadn’t been missing for 10 years, he just hadn’t made much news. He had been working at the Salmon Cigar Store “Kitty Corner from the Owyhee Hotel” since it opened in 1908. When Edmund Salmon died in 1922, Hannifin took over. It became a Boise institution, selling cigars, pipe tobacco, beer, soda, comic books, and “gentlemen’s magazines.” The Hannifin family owned the place until the late 1960s. The store retained the name until it finally closed in 2019. John Hannifin died at age 87 in 1980.

The building where Hannifins was housed is one of the oldest commercial buildings in Boise, constructed in 1897. It was originally part of the Beckworth Building, home to a grocer, a hardware store, and a clothing store. The building where Hannifin’s was located for all those years is one of several in the Lower Main Street Commercial Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, Hannifin’s looks much the same on the outside of the building. Ryan Salamon, the barber who renovated the building for his new shop, kept many historic touches including the cast iron stove in the middle of the building. The Hannifin’s sign once above the front door is now displayed inside of the Belmont Barber Shop.

Inside the barber shop where Hannifin's once was.

Inside the barber shop where Hannifin's once was.

Published on November 21, 2021 04:00

November 20, 2021

When the Idaho (but not that Idaho) burned (Tap to read the story)

Idaho's Lake Coeur d'Alene was known especially for its steamships that slid back and forth across the waters from the 1880s to the 1930s. One of the better-known boats was the sidewheeler, Idaho.

Would it surprise you to learn that a steamboat named Idaho burned to the waterline and sank on November 26, 1866? This Idaho never knew Lake Coeur d'Alene. Instead, it worked the waters of the East River, New York City.

The Idaho was one of the newer boats of the Brooklyn Ferry Company. Shortly after leaving the dock about 7:10 in the evening, what may have been a smoldering fire broke through the ferry's deck and started to rapidly consume the Idaho. Fortunately, a sister ferry, the Canada, was nearby. The captain of the Canada pulled alongside the burning boat long enough for most of the passengers to jump aboard. Heavy flames forced the Canada to pull away before everyone could get aboard. A woman and her child jumped into the water and were saved from drowning by two men. One of the men suffered serious burns in the rescue, but there were no fatalities.

The Idaho, which was not insured, was a total loss. Authorities estimated it was worth $64,000.

The fire aboard a boat named after the state didn't cause a ripple in Idaho newspapers at the time, so it falls to me to break the news to you 155 years later. You're welcome.

[image error]

Would it surprise you to learn that a steamboat named Idaho burned to the waterline and sank on November 26, 1866? This Idaho never knew Lake Coeur d'Alene. Instead, it worked the waters of the East River, New York City.

The Idaho was one of the newer boats of the Brooklyn Ferry Company. Shortly after leaving the dock about 7:10 in the evening, what may have been a smoldering fire broke through the ferry's deck and started to rapidly consume the Idaho. Fortunately, a sister ferry, the Canada, was nearby. The captain of the Canada pulled alongside the burning boat long enough for most of the passengers to jump aboard. Heavy flames forced the Canada to pull away before everyone could get aboard. A woman and her child jumped into the water and were saved from drowning by two men. One of the men suffered serious burns in the rescue, but there were no fatalities.

The Idaho, which was not insured, was a total loss. Authorities estimated it was worth $64,000.

The fire aboard a boat named after the state didn't cause a ripple in Idaho newspapers at the time, so it falls to me to break the news to you 155 years later. You're welcome.

[image error]

Published on November 20, 2021 04:00